CHAPTER 6

Monetary Policy during the Pandemic and the Quantitative Easing (QE) Trap

The COVID-19 pandemic recession, which struck in early 2020, threw the global economy from Case 3 into Case 2, forcing governments and central banks to make a dramatic policy shift to deal with the life-threatening economic downturn. The subsequent recovery then pushed prices sharply higher because of both supply-side disruptions and Sustainable-Driven Goals (SDGs)-driven higher energy prices, fueling strong inflationary concerns. Those concerns were augmented even further by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

When the pandemic hit, people had to stay home to avoid being infected, and millions if not billions of households and businesses suddenly found themselves with drastically reduced incomes. The gross domestic product (GDP) in most countries contracted precipitously as lockdowns, voluntary or otherwise, were implemented. In the second quarter of 2020, the GDP shrank by as much as 8.94 percent in the United States, 11.63 percent in the Eurozone, and 7.95 percent in Japan—the worst figures seen since the Great Depression in the 1930s. The United States, for example, went in just two months from reporting its lowest unemployment rate in 50 years to its highest in 90 years. Only Taiwan, which was the first country to report the existence of the new virus to the World Health Organization (WHO), managed to contain infections from the start of the pandemic and was thereby able to maintain economic activity throughout most of 2020. But even Taiwan was struck by a super-spreader nicknamed “Lion King” in the spring of 2021 and by the Omicron variant in 2022.

This sudden loss of income, in turn, forced affected businesses and households to withdraw savings or borrow money to make ends meet, as they still had to pay rent and other expenditures. These actions caused an abrupt tightening of financial markets, as the savers who used to supply funds to the market began withdrawing their savings, while borrowers who had been absent since 2008 returned in massive numbers to secure working capital. This behavioral shift pushed the economy into Case 2.

As a result, borrowing costs skyrocketed in most markets in early March 2020, further worsening the predicament of businesses already hit hard by the coronavirus. This can be seen from the sudden jump in corporate bond yields in the United States and Europe (Figure 6.1). In Japan, the financial position diffusion index DI in the Bank of Japan (BOJ)'s Tankan survey (Figure 6.2) plunged after the pandemic recession began (see oval at right edge of graph), with the speed of the decline reminiscent of the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 (middle oval) and the banking sector “meltdown” in 1998 (left oval). But whereas those two crises were triggered by lender-side factors—that is, a financial crisis—the tight financial conditions seen at the beginning of the pandemic were the result of a dramatic drop in borrower revenues.

FIGURE 6.1 Corporate Bond Yields Returned to Pre-Pandemic Levels but Increased again in the West due to Inflationary Fears

Notes: Data as of March 11, 2022.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC

FIGURE 6.2 Financing Challenges of Japanese Enterprises

Source: BOJ Tankan

A weaker economy is usually accompanied by lower interest rates, but this time the opposite happened, and the collapsing economy ushered in sharply higher rates. Central banks responded by acting as lenders of last resort in order to restore the normal workings of financial markets. For the first time since 2008 for the West and since 1990 for Japan, central bank monetary easing became absolutely essential, which was not the case during the pre-2020 balance sheet recessions.

Central banks around the world took up the challenge and injected massive amounts of funds to calm the markets. Even though the COVID-19 shock was not a financial crisis originating with the lenders like the post-Lehman GFC, the amounts provided by central banks this time were far larger than in 2008. These amounts can be seen as the post–February 2020 jump in the monetary base shown in Figures 2.12 to 2.14 and 2.17. In addition, the Fed quickly took interest rates back to zero.

The Fed also provided liquidity directly to nonfinancial companies. Such direct lending to the private sector had always been taboo. But by directly purchasing corporate bonds, the Fed eased market concerns about businesses' survival and reassured investors, who then drove bond yields lower. The Fed's concern was that if businesses were allowed to go under due to revenues lost during the pandemic, the economy would be unable to recover—and banks' bad loans would surge—even if a medical solution to the coronavirus was eventually found. As a result of these aggressive easing measures, corporate bond yields returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 6.1).

Corporate Bond Yield Movements in Japan and Europe Also Relatively Mild

In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) not only resumed quantitative easing (QE), but also began supplying funds at negative interest rates. The yields on Eurozone corporate bonds consequently returned to pre-pandemic levels after blowing out initially (Figure 6.1). In Japan, the BOJ restarted QE in response to the sudden increase in borrowers.

The central banks' sense of crisis regarding businesses' ability to endure the pandemic recession was shared by governments, which implemented a variety of fiscal measures to reduce companies' costs in the short term, such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) in the United States. European and Japanese governments' massive loan guarantee programs have also helped to ease concerns about companies' ability to survive. The European Union (EU) unveiled a €750 billion rescue package to be funded by a Euro-wide bond issue, the first since the creation of the euro.

These measures also prompted governments to become huge borrowers as they provided financial support to help keep businesses and households viable. The measures had to take the form of direct payments from the government to individuals and businesses—as opposed to public works projects—because people could not work in close proximity to each other during the pandemic. The corresponding expenditures added massively to government budget deficits.

Capital Markets Have Shrugged Off Central Bank Financing of Fiscal Deficits

That raises the question on how to finance the resulting budget deficits. A significant portion of the economic measures implemented thus far—including the $3.9 trillion spent by the United States in 2020—has been effectively funded by central banks' QE, as can be seen by the jump in the post-2020 monetary base previously noted. This had to happen because only central banks can provide the trillions of dollars needed so quickly. Although the private sector has been a large net saver since 1990 in Japan and since 2008 in the West, only a central bank can swiftly provide the sums needed when the government's borrowing requirements jump so suddenly due to what Fed Chairman Jerome Powell called a natural disaster.

While economists have long viewed this sort of de facto central bank financing of budget deficits as taboo because of its tendency to produce pernicious inflation, capital markets have hardly blinked an eye. There were at least five reasons for the market to “think differently” this time.

First, there was little reason to fear inflation during the lockdowns themselves because supply far exceeded demand. In fact, if central banks had not provided support for government fiscal stimulus, economies might well have fallen into a vicious deflationary cycle of bankruptcies and job losses.

Second, the failure of central banks to achieve their own inflation targets despite purchasing huge amounts of government debt under QE since 2008 has taught the markets that QE would not necessarily result in inflation. Although this represented a tremendous loss of face for the central banks and economists who pushed for such policies, it would appear that their failure has helped keep the markets calm during the pandemic.

Third, unlike in an ordinary natural disaster, the economy's capital stock has not been impaired, which means there will be no reconstruction demand after the pandemic has run its course.

Exchange Rates Have Also Held Steady Because Central Banks Acted Together

Fourth, the impact on exchange rates has been minimal since central banks around the world have adopted similar policies. In all past instances where such monetization of the fiscal deficit led to pernicious inflation, it did so by triggering a collapse of the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market, thereby leading to a dramatic rise in the cost of imports. Basically, people feared that central bank “money printing” to finance the government deficit would cause the national currency to lose value, and they rushed to exchange it for other currencies.

This time, however, all central banks are doing the same thing, making it difficult for people to know where to take their money, and exchange rates have been very stable. Although gold and cryptocurrencies did appreciate, this has done nothing to increase domestic inflation rates.

Last but not least, the businesses and households that suffered most from the pandemic were those with little savings. Many went bankrupt as a result. Having realized that it is important to have sufficient savings for a rainy day, those who survived the recession are likely to place a high priority on replenishing savings depleted during the lockdown. Many may go far beyond the pre-pandemic levels of savings, just to be on the safe side, especially with new variants of the virus constantly emerging to threaten the economic recovery.

For some households and businesses, the most important impact of the pandemic for the long term may come from a renewed appreciation of having sufficient savings. This is the opposite of the pre-pandemic mindset in the West, where politicians, academics, and financial types alike bashed the corporate hoarding of cash as a suboptimal use of capital. But those precautionary hoardings helped the companies withstand the pandemic in no small way.

In the new paradigm, share buybacks with borrowed money, which reduced companies' savings and weakened their ability to withstand the pandemic and other external shocks, are likely to be viewed with caution. A renewed appreciation of savings also means post-pandemic economic growth will be weaker but the economies themselves will be more resilient. The probability of an economy returning to Case 3 after the pandemic also increases if its private sector collectively becomes a net saver as it tries to replenish savings that were depleted during the pandemic.

This suggests that central bank financing of fiscal deficits has very different implications during ordinary times and during a pandemic. It is a policy that can be safely employed during a pandemic even if it should be forbidden under normal circumstances.

Inflation Returns

Starting in the spring of 2021, inflation driven by supply constraints became rampant in the United States and Europe as uneven waves of infection hit different parts of the world at different times. Since products made from components fabricated around the globe cannot be completed until all the parts are in place, these rolling waves of COVID-19 disrupted and delayed production and shipments everywhere. It was said, for example, that the shortage of integrated circuit (IC) chips could not be easily addressed because the machines needed to produce those chips also required chips that were in short supply.

For inflation to return on a sustained basis, however, there has to be some improvement in the two factors that pushed the advanced countries into Case 3 in the first place. Those two problems are inferior returns on capital relative to emerging economies and balance sheet concerns following the bubble's collapse, both of which led to an absence of borrowers. There have been signs of improvement in the latter, but little progress on the former. A new factor that emerged during the last two years, the global push toward renewable energy (discussed later), is also likely to result in more domestic investment. But without significant progress on one or both of the two problems previously noted, the economy may still be pulled toward a non-inflationary Case 3 state over the medium term. In the meantime, central banks will have their hands full fighting inflation driven by supply shortages, which do not respond well to monetary tightening.

The Return of Fiscal Stimuli after 50 Years

One key difference between the COVID-19 recession and the post-2008 balance sheet recession is the size of government's fiscal response. In 2008, tens of trillions of dollars in asset value vanished when housing bubbles burst on both sides of the Atlantic. That created a massive and urgent need for the private sector to repair millions of underwater balance sheets, forcing the sector to save as much as 10 percent of GDP per year in the immediate aftermath of the Lehman Brothers' collapse, as is noted in Chapter 2.

In spite of the huge loss of wealth and massive private-sector deleveraging, the best the newly elected Obama administration could manage to extract from the Republican opposition was a two-year, $787 billion package, which comes to about 2 percent of GDP per year. That 2 percent was simply not enough to turn the economy around.

Moreover, there was no follow-up fiscal package because the Republicans, who took control of the lower house of Congress after the mid-term elections in 2010, sought to balance the budget even though the U.S. private sector continued to generate massive excess savings in order to repair its balance sheets for years afterward. The result was a long and painful balance sheet recession that lasted nearly a decade.

This time, the U.S. government administered a fiscal stimulus worth $3.9 trillion—almost 20 percent of U.S. GDP—in 2020 alone. The Biden administration then passed a $1.9 trillion economic support package followed by a $1.2 trillion infrastructure package in 2021. These are massive fiscal programs that even Lawrence Summers warned might incite inflation. There is no doubt that some elements of these large fiscal initiatives have contributed to upward pressure on prices in a recovering economy that is also suffering from supply mismatches. This is also the first time since the war in Vietnam, half a century ago, that concerns over fiscal policy shifted from “too little” to “too much.”

The Energy Sector Will Not Return to Pre-2020 World

One sector of the economy that will not return to the pre-pandemic Case 3 world is the energy sector. Because of the recent groundswell of concern over climate change, the business environment for fossil fuel producers has changed drastically. Financial institutions, including central banks, are now under pressure to reduce the flow of funds to fossil fuel–related industries.

This shift in focus to SDGs was bolstered by President Joe Biden, who is deeply worried about the existential threat to humankind posed by climate change. He is also trying to make up lost ground, as his predecessor denied the very existence of the threat and did nothing about it for a full four years. Japan has also announced some fairly ambitious plans, with then–Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga declaring in late 2020 that the nation would be carbon neutral by 2050, effectively eliminating all emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Europeans are far ahead on this issue, and the Chinese are trying to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

But no matter how necessary the transition to renewable energy may be, there is simply not enough renewable energy at present to keep economies going. As a result, the recent move to discourage investment in fossil fuels has already prompted energy shortages in Europe and China, resulting in sharply higher energy prices and stagnant economic growth.

In the past, investments in fossil fuel were carried out in expectation of ever-greater demand for such fuels in the future. But many governments around the world are now stipulating that only electric vehicles may be sold after a certain date. And those new restrictions are likely to spread to other machines and transportation equipment that are currently powered by fossil fuels.

That means those businesses that are contemplating investments in fossil fuel extraction must be able to recover their costs in a drastically shorter time frame. The growing tendency for society to view such action as being morally suspect, if not evil, has also dissuaded many companies from pursuing such projects. As a result of these fundamental changes in the market, supply is falling behind demand, and prices are rapidly rising.

The unfortunate truth is that high prices for fossil fuels are essential in order both to increase investment in renewable energy and to justify investment in the fossil fuels that are still needed to avert energy shortages—but whose cost must be quickly recovered. Indeed, it is unrealistic to think the fundamental energy transition the world seeks is possible without high fossil fuel prices.

One must also be realistic about the duration of the transition period. To fully replace fossil fuels with renewable energy will take decades. The only realistic solution that can shorten the time needed to go carbon-free is nuclear power. But as Toyota Motor chairman Akio Toyoda commented on December 17, 2020,1 Japan would need ten more nuclear power plants if all the cars in the country had to run on electricity. If all the machines in the world that are currently powered by gas, oil, and coal had to run on electricity, the number of additional nuclear power plants needed would be absolutely staggering.

These hard realities are likely to result in bouts of “SDG fatigue” during the long transition period, especially when economies suffer from repeated energy shortages. But such fatigue and the resulting political pushback could easily lengthen the transition period to the detriment of the planet. To avoid such setbacks, it is essential that energy shortages are avoided.

It is difficult to expand the supply of anything, including fossil fuel, when its use is almost certain to face severe restrictions in the near future. The only way to secure a sufficient supply of coal, gas, and oil to keep economies running in the near term while accelerating the deployment of renewable energy in the longer run is to have high fossil fuel prices now. That means high and possibly volatile energy prices are here to stay.

Central banks responsible for price stability must recognize that even if the rest of the economy is trying to return to the disinflationary world that existed before the 2020 pandemic, the energy sector is not. The SDG concerns that emerged during the last two years mean inflationary pressures in energy-related fields are not only not transitory but are actually necessary for the least disruptive transition to renewable energy. The higher energy prices brought about by the Russian invasion of Ukraine may reverse themselves if and when peace returns. But that level is still likely to be higher than the prices seen prior to the pandemic.

That means pursued economies will face high energy prices and reduced purchasing power for years to come. To the extent that the stagflation of the 1970s was triggered by high oil prices, it is possible that a similar phenomenon will be observed as the transition to renewable energy is accompanied by higher energy prices and slower economic growth.

SDG Concerns May Return Economies to Case 1

Over the medium term, SDG concerns could bring far-reaching changes to the global economy that may even push the advanced economies out of Case 3, where they are today, and into Case 1. This is because replacing everything that currently runs on gas, oil, or coal with electrically powered equipment will require huge investments. And both businesses and households are likely to finance a substantial portion of those investments with borrowings.

A greater focus on climate change may also slow down the pace of globalization. Some in Europe and elsewhere are already calling for the erection of barriers against imports from countries that have not done enough to address climate change. Indeed, this could undo some of the globalization that has taken place since the postwar introduction of the U.S.-led free trade system as businesses bring production back home. The concept of pursued economies will also lose some of its relevance if concerns over SDGs slow down the process of globalization. In addition, the recent supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic may also force businesses to nearshore production. These developments are likely to retard globalization while adding to domestic inflationary pressures.

Normalizing Post-Pandemic Monetary Policy Will Be Challenging

Higher prices brought about by pandemic-driven supply chain disruptions and higher energy prices brought about by climate change concerns are not something a central bank can address. But these higher prices, together with the return of long-awaited fiscal activism, signal a change in the environment surrounding monetary policy.

All unconventional monetary policy since 2008—including QE, forward guidance, and negative interest rates (in Europe and Japan)—has been implemented because the fiscal policy needed to address balance sheet recessions was not forthcoming. The return of fiscal policy—at least in the United States—along with higher energy prices, means central banks should wind down these nonconventional policies and restore their inflation-fighting credentials.

Such credentials are necessary because the fear of inflation is weighing heavily on consumer confidence and on the economy in general. For example, the University of Michigan's consumer confidence index for November 2021 dropped to its lowest level in over a decade—lower even than during the worst of the lockdowns—because of consumer concerns over inflation. Moreover, no matter how confident the Fed might be that prices will eventually stabilize once supply constraints are removed, no one will know for sure for two or three years.

In the meantime, if market participants perceive the Fed to be falling further behind the curve on inflation, they could start selling bonds to protect themselves from inflation, sending long-term interest rates rocketing higher and pushing the economy into recession. If the Fed is no longer credible as an inflation fighter, the chances of such a bond market sell-off will increase sharply. It would also take a great deal of time and effort for the Fed to regain the market's confidence and bring long-term rates back down.

Recognizing this risk, the Fed drastically shifted its stance on inflation and began normalizing monetary policy in late 2021. This process, as indicated in Figure 4.6, will be a huge challenge as it entails raising interest rates while reabsorbing the enormous amounts of liquidity injected into the economy during both the post-2008 balance sheet recession and the post-2020 pandemic recession. To do so, the Fed must sell the government and other bonds it has acquired since 2008. Given the huge amounts involved, this was going to be a difficult and volatile period for the markets even if the real economy had stayed on a recovery path. If this process is not handled correctly, the resulting market volatility could even harm the real economy. But a failure to mop up the liquidity could force the Fed to carry out an even more difficult monetary tightening later on if and when private-sector borrowers return (this point is discussed further a bit later).

This process of normalization was actually attempted and aborted once before by the Fed. When the Fed announced in May 2013 that it was going to begin reducing, or tapering, its purchases of government bonds under QE, the market responded badly and pushed long-term bond yields sharply higher in what came to be known as the “taper tantrum.” It took months for the market to regain its composure after that shock.

The tapering was followed by nine interest rate hikes starting in December 2015 along with so-called quantitative tightening (QT) beginning in October 2017. Some of these actions also led to market turmoil. However, the normalization process was aborted when the economy showed modest signs of weakness in the second half of 2019, and was scuttled altogether when the pandemic hit in February 2020.

Market volatility may increase during a post-QE normalization of monetary policy because it will be the first time in history that a recovery starts with massive amounts of liquidity already present in the financial sector owing to QE. Since 2008, the Fed has supplied some $5.5 trillion under quantitative easing, and the ECB, Bank of England (BOE), and BOJ have injected €5.28 trillion, £992 billion, and ¥581.8 trillion, respectively (Figures 2.12 to 2.14 and Figure 2.17).

As a result, the U.S. monetary base rose from 6.3 percent of GDP in September 2008 to 27.5 percent in December 2021. The monetary base increased from 9.4 percent to 47.9 percent of GDP in the Eurozone, from 5.4 percent to 49.3 percent in the United Kingdom, and from 17.1 percent to 122.6 percent in Japan. As a percentage of GDP, these amounts represent a 4.4× increase over the level when Lehman Brothers collapsed for the United States, a 5.1× increase for the Eurozone, a 9.1× increase for the United Kingdom, and a 7.2× increase for Japan. Multiples over the pre-Lehman era are even larger for reserves in the banking system (Figure 6.3).

These increases in the monetary base imply that if businesses and households were to resume borrowing in earnest (i.e., return to Case 1) and the pre-2008 relationship between monetary aggregates seen in Figures 2.12 to 2.14 were to be restored, credit and the money supply could increase as much as fourfold in the United States, sending the inflation rate sky-high. The only reason these countries have not experienced such runaway inflation is that their economies have been in Case 3, with very weak private-sector borrowing—in fact, businesses and households have been saving money or paying down debt despite near-zero interest rates (Figure 1.1).

That means central banks will have to slash excess liquidity to a fraction of current levels by selling their holdings of government bonds before borrowers return. But that would still be a nightmare for the economy and the bond market because they have never experienced central banks unloading so many bonds in the market. The subsequent fall in bond prices would mean higher borrowing costs for everybody.

Figure 4.6 in Chapter 4 already indicated what would be needed to normalize monetary policy in the United States. It showed that both interest rates and the monetary base will have to be normalized, a task that had never been attempted before 2015. Alan Greenspan, who brought down interest rates to 1 percent after the dot-com bubble collapsed in 2001, did succeed in normalizing interest rates by raising the policy rate 17 times starting in 2004, taking it up to 5.25 percent. But he was simultaneously allowing the monetary base to grow, albeit slowly. In other words, at the same time as he was tightening monetary policy by raising interest rates, he was also easing policy by allowing the monetary base to grow. He could do this because he and his predecessors did not implement QE: for him, the normalization process was limited to interest rates.

FIGURE 6.3 QE Central Banks Must Reduce Reserves Massively before Borrowers Return to Avoid Credit Explosion

Note: The Bank of England (BOE) and the Fed suspended reserve requirements in March 2009 and March 2020, respectively. Post-suspension figures are based on assumption that original reserve requirements are still applicable.

Sources: Nomura Research Institute, based on BOJ, Federal Reserve Board (FRB), ECB, BOE, and Swiss National Bank (SNB) data

This time the central banks have to both raise interest rates and shrink the monetary base to normalize policy. The difficulty inherent in the latter task is one of the costs of QE (or any central bank financing of budget deficits) and is the reason why central bankers traditionally tried to avoid monetizing fiscal deficits in the first place.

The Need for a Shock Absorber

The difficulty surrounding the task of normalizing the monetary base was acknowledged by the Fed in September 2014 when it reversed the order of policy normalization. Prior to this date, the Fed's official position on unwinding QE was that it would normalize its balance sheet (i.e., shrink the monetary base) first and only then set about normalizing interest rates. But as the challenges surrounding the former became clearer, the order was reversed for the reasons discussed in the following.

To begin with, the bond market had never seen the Fed unload trillions of dollars in government bonds, but it had plenty of experience with rate hikes. By raising interest rates first and normalizing its balance sheet only after rates had returned to sufficiently high levels, the Fed sought to buy itself a shock absorber in case the balance sheet normalization process (or other factors) triggered a collapse of the bond market. In other words, if bond prices tumbled for any reason, the Fed could lower interest rates to soften the shock.

Although the lack of private-sector borrowers in 2015 suggested there was no need to rush the normalization process, central banks that implemented QE must move faster than those that did not. This is because bond yields can surge if the central bank tries to reduce the supply of liquidity just as demand for funds from private-sector borrowers is recovering. Bond yields can also go up if the market starts to believe the central bank has fallen behind the curve on inflation after injecting so much liquidity. Sharply higher bond yields, in turn, will have highly unpleasant consequences for the economy and the market.

If the normalization process is to proceed smoothly, therefore, central banks that have implemented QE must start the process before private-sector demand for funds picks up in earnest. This is because bond yields can go up only so much if there are no private-sector borrowers, even if the Fed starts to unload its bonds.

The Fed Is More Concerned about Real Estate than Equities

Another reason for the Fed to normalize monetary policy was the emergence of asset price bubbles in certain sectors, and especially in the U.S. commercial real estate market. As is noted in Chapters 2 and 4, mini-bubbles are possible even in balance sheet recessions because the disappearance of traditional borrowers forces fund managers to buy existing assets that are expected to appreciate. But such bubbles are most unwelcome for central bankers: after all, it was the collapse of the real estate bubble in 2008 that triggered the Western world's worst recession since World War II.

As is noted in Chapter 4, U.S. commercial real estate prices are now 68 percent higher than at the peak of the bubble in 2007 (Figure 4.7). House prices have also exceeded the previous bubble peak reached in 2006 by more than 51 percent. In San Francisco, which has benefited from its proximity to booming Silicon Valley, house prices are now 58 percent higher than at the previous bubble peak.

The central bank's economic support measures during the pandemic have also pushed the price of companies' stock and bonds sky-high, even though many issuers are far less profitable and creditworthy than they were prior to COVID-19. Electric vehicle (EV) maker Tesla, for example, reached a market capitalization that was twice that of Toyota's while producing only one twenty-ninth the number of cars in 2020. In other words, there is a bubble in asset markets driven by central bank liquidity, with investors happy to overlook potential risks. Although it is unfortunate that bubbles were formed, governments and central banks did what they had to do given the lives and livelihoods at stake, at least for the first year of the pandemic.

With asset price bubbles already evident in these markets, it would hardly be surprising if monetary authorities felt pressured to act to avoid a further expansion of these bubbles and their unpleasant aftermath. Whether or not the Fed is able to handle the collapse of mini-bubbles as it pursues normalization depends on the amount of private-sector leverage in the system. If parts of the private sector are highly leveraged, a burst bubble could lead to a bigger mess, while if the leverage is modest, any resulting correction should be manageable.

A look at the U.S. economy from the standpoint of private-sector leverage shows that the household sector, the trigger of the last crisis, has steadily reduced its leverage since then (Figure 2.5). Even in places like San Francisco, where house prices are in bubble territory, most of the high-priced deals are said to involve all-cash offers.

Unfortunately, that is not the case with commercial real estate, where most deals are done with borrowed money. Few businesses buy commercial properties with cash. Fed officials are therefore rightfully concerned about this market and have already imposed strong macro-prudential measures to clamp down on real estate lending since 2016.

Real estate bubbles are not only a U.S. problem. Thanks to the ECB's QE and negative-interest-rate policies, European real estate prices have risen sharply since 2015 (Figure 2.4). In the Netherlands, for example, house prices are already well beyond the previous peak reached in 2007. Even in Japan, real estate prices in popular areas have surged under negative interest rates, astronomical amounts of QE, and the changes to the inheritance tax that are noted in Chapter 5. Prices in the Ginza district in central Tokyo reached a new all-time high in 2017 for the first time since the bubble burst 27 years earlier.

If these bubbles continue to expand and eventually burst, economies will find themselves back at square one facing long and painful balance sheet recessions. That would signal another iteration of the bubble-and-balance-sheet-recession cycle that is noted in Chapter 4 and would also mean that all the efforts to fix the economy since 2008 had been in vain.

The First Attempt at Normalization

As is previously noted, the Fed's first attempt to normalize interest rates after the GFC began on December 16, 2015, when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) unanimously approved the first increase in the federal funds rate in nine years. At the time, the U.S. private sector was still running a huge financial surplus as businesses and households continued to repair their balance sheets. Raising interest rates when the private sector is not borrowing money is a tricky business. Indeed, the Chicago Fed's financial conditions index often indicated an easing of borrowing conditions, as is shown in Figure 4.3, in spite of nine policy rate increases from 2015 to 2019. But that did not deter the Fed from raising rates because the key reason for doing so was to provide itself with a shock absorber.

At her press conference on the day of the first hike, Fed Chair Janet Yellen said that “if we do not begin to slightly reduce the amount of accommodation, the odds are good that the economy would end up overshooting both our employment and inflation objectives.”2 She also said that if the Fed were to postpone the normalization process for too long, it “would likely end up having to tighten policy relatively abruptly at some point,” thereby increasing the risk of recession.

In a January 6, 2016 interview with CNBC, then–Fed Vice Chair Stanley Fischer declared that market expectations for the pace of tightening were “too low.”3 He also said the Fed needed to proceed with normalization in order to “head off excessively high asset prices,” referring to the mini-bubbles in both stocks and commercial real estate. Fischer warned that such high asset prices would be “creating big messes in the markets,” which is shorthand for the eventual need to raise interest rates rapidly, triggering a plunge in the value of stocks, bonds, and other assets.

These comments by Fed officials suggest they were fully cognizant of the danger of waiting until the 2-percent inflation target was reached, when the private sector would most likely have already resumed borrowing. The pronouncements also indicate the Fed was actively trying to manage market expectations as it embarked on a difficult journey.

Private-sector demand for borrowings can be expected to increase when balance sheets are repaired, thereby adding to inflationary pressures. Borrowings, however, are unlikely to recover to golden-era levels now that advanced countries are in the pursued phase. Still, even if growth in the money supply and credit were one-tenth of the monetary base multiple, for example, 40 percent instead of 400 percent, inflation rates could still rise to highly unpleasant levels unless the central bank drains the excess liquidity it pumped into the economy under QE.

QE Trap: Tug-of-War between Monetary Authorities and Markets

Even with the precautions previously noted, the first rate hike in nine years sparked tremendous market volatility in early 2016, with the Dow falling as much as 12 percent from its peak. Volatility picked up not only because many market participants had gotten addicted to easy money, but also because the Fed started tightening when the inflation rate was still well below target.

But the Fed's determination not to fall behind the curve on both asset prices and the general level of prices was demonstrated when John Williams, then president of the San Francisco Fed, said late in March 2016 that the 30 percent decline in share prices on Black Monday in October 1987 had had little impact on the real economy. He also cited economist Paul Samuelson's quip that the stock market has predicted “nine out of the last five recessions” in an attempt to emphasize that the stock market and the real economy are not the same thing.4 Vice Chair Fischer also noted that the U.S. economy was largely unaffected by large swings in equity prices in 2011. The fact that these remarks came out as soon as markets regained their composure underscores the sense of urgency at the Fed regarding the normalization of monetary policy and suggests it was hard at work on managing expectations of further rate hikes.

First Iteration of QE Trap

The January 2016 turmoil was the first domestic iteration5 of what the author dubbed the “QE trap” in his previous book6—a repeated tug-of-war between investors and the monetary authorities. In this trap, a central bank that has implemented QE but is now raising interest rates has to take a step back if the rate increase results in market turmoil. But once the market regains its balance, the central bank resumes its drive to normalize monetary policy. That, in turn, prompts another round of volatility. This sort of back-and-forth iteration of conflict between the markets and the authorities has been observed frequently since then.

Figure 6.4 illustrates the possible behavior of long-term interest rates in two scenarios: one in which the central bank has engaged in QE (thick line) and one in which it has not (thin line). When a central bank takes interest rates to zero after a bubble bursts but does not resort to QE, long-term government bond yields will still fall sharply because the economy is weak and government is the only borrower issuing fixed income assets denominated in the home currency. This fall in government bond yields is the self-corrective mechanism of economies in balance sheet recessions that is noted in Chapter 2.

FIGURE 6.4 QE “Trap” (1): Long-Term Interest Rates or Exchange Rates Could Go Sharply Higher When QE Is Unwound

Once the economy begins to show signs of life after a few years, the central bank will raise short-term rates at a pace deemed appropriate given the extent of the economic recovery and inflation. Bond yields will rise gradually in line with both the short-term interest rate and the recovery in private-sector loan demand. At that point, people will be happy and relaxed because the recovery has finally arrived. This is the usual pattern of monetary policy normalization and bond yields in an economic recovery.

A central bank that has implemented QE, meanwhile, faces a very different set of circumstances. In this case, long-term rates will fall further and faster at the outset than in the non-QE case because the central bank is also buying huge quantities of government bonds. Such low rates are likely to support asset prices via the portfolio rebalancing effect and bring about economic recovery a little sooner (t1) than in the economy where there was no QE (t2).

Once the recovery is within sight, however, the market starts to gird for trouble as rate hikes and an eventual mop-up of excess liquidity by the central bank appear increasingly likely. Market participants must brace themselves because there is over $3.66 trillion in long-term bonds that the central bank must sell off to drain the excess reserves, as noted earlier.

If the Fed has to sell those bonds, bond prices will fall and yields will go up. If it holds on to the bonds until maturity, the Treasury will have to sell an equivalent amount of bonds on the Fed's behalf to absorb the excess liquidity (this is explained further a bit later). And if the Fed wants to postpone the normalization of its balance sheet, it will have to raise interest rates that much faster and higher to stay ahead of the curve on inflation. The resulting rise in interest rates may also trigger a stock market crash.

To the extent that market participants have become addicted to QE—known in the market as the “central bank put”—the reverse portfolio rebalancing effect (i.e., the negative wealth effect) brought about by the central bank's normalization of monetary policy would be equivalent to going through painful withdrawal symptoms. From the standpoint of the policy authorities, however, withdrawal symptoms alone are not cause enough to discontinue treatment of the patient. While treatment may be paused temporarily if symptoms become too severe, it will need to resume as soon as the market stabilizes lest the central bank fall behind the curve. It was precisely this kind of mindset that underpinned the previously noted remarks by Stanley Fisher and John Williams in March 2016.

Global QE Trap

There is also an international dimension to the QE trap. Indeed, the strengthening of the dollar since the Fed's September 2014 announcement of its intention to normalize interest rates can be seen as a manifestation of a global QE trap.

Soon after the Fed's announcement, the BOJ eased policy again and the ECB began indicating it would follow with its own version of QE. The prospect of higher interest rates in the United States and lower interest rates in Japan and Europe then prompted a rush of capital outflows from these two regions into the U.S. bond market in search of higher yields. Those inflows pushed the dollar sharply higher but also prevented a rise in long-term U.S. interest rates, thereby propping up the bubble in U.S. commercial real estate.

Between the summer of 2014 and the beginning of 2016, the dollar climbed as much as 48 percent against the Mexican peso and as much as 37 percent against the Canadian dollar (Figures 6.5 and 6.6). Not only are both countries key U.S. trading partners, but many U.S. companies have factories in one or both. U.S. workers who must compete with factories in these countries were therefore rightfully worried about such a major appreciation of the U.S. currency.

Presidential candidates Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders capitalized on this situation. Their stances against free trade have proved very popular among the blue-collar workers who have suffered as the dollar rises. Trump even proposed levying a 35 percent duty on imports from Mexico to help U.S. workers and companies fighting imports from that country.

Calls for protectionism became so loud in 2016 that even Hillary Clinton was forced to declare her opposition to the current form of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an agreement she herself had helped negotiate. Her uncharacteristic shift can be attributed to the fact that the U.S. dollar's substantial appreciation made the free-trade argument a difficult one to sell in the United States. Indeed, when she accepted the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 2016, the entire arena was filled with signs exclaiming “No to TPP!”

FIGURE 6.5 Mexican Peso versus U.S. Dollar

Source: FRB

FIGURE 6.6 Canadian Dollar versus U.S. Dollar

Source: FRB

Since protectionism can quickly destroy world trade, the Fed had to curb its rate hikes until the presidential election was over. In this round of the QE trap, therefore, the Fed had to temper its response because of the surging dollar rather than falling stock prices or rising bond yields.

The stock market's surprisingly strong reaction to the Trump victory in November 2016 and the remarkable stability of the dollar during the Trump years gave the Fed a window of opportunity to raise interest rates eight times in the next two years, thereby making up for time lost during the election campaign. How the dollar remained stable during the Trump years in spite of eight rate increases by the Fed is explained in Chapter 9. The rate hikes gave the Fed the shock absorber it needed to embark on the main event, that is, the normalization of its bloated balance sheet.

The Difficulty of Normalizing the Central Bank Balance Sheet

If normalizing interest rates with QE is difficult, normalizing the central bank's balance sheet is no easier. Some have argued that this process should be relatively straightforward since banks have the excess reserves supplied under QE to buy the bonds being sold off by the central bank, but there is an asymmetry involved here.

When the central bank was acquiring the bonds under QE, there was no private-sector demand for borrowings. That means interest rates were low and bond prices were high. But when the time comes for the central bank to sell the bonds, both the economy and private-sector demand for borrowings have presumably recovered. Interest rates will therefore be higher and bond prices lower. The fact that the central bank is selling bonds at a time when the private sector also wants to borrow means interest rates could go much higher than when the central bank was a buyer. The situation can be further exacerbated if the central bank is viewed as being behind the curve on inflation. That is also why the Fed wanted to undo QE in 2017, before private-sector borrowers returned and when the asymmetry problem was minimal.

Many in the market, however, became complacent after Ben Bernanke assured them the Fed would hold the bonds until maturity. He indicated that instead of selling bonds to absorb excess liquidity, the Fed would mop up the liquidity by not reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds it held. Hearing this, many in the market assumed that nothing terrible would happen to the bond market even if the Fed normalized its balance sheet, as long as it did not sell the bonds. But this complacency is also problematic.

When a government bond matures, the government usually issues a refunding bond to obtain funds from the private sector to pay the holder of the maturing security. Because of the huge quantity of government bonds issued in the past, the market for refunding bonds in both Japan and the United States is three to four times the size of that for newly issued debt to finance government expenditures.

Ordinarily the issuance of refunding bonds is not thought to produce significant upward pressure on interest rates because the proceeds will be paid to private-sector holders of maturing government debt who are likely to reinvest those funds in government debt again. In other words, the money will stay in the bond market. Bond market participants therefore relax when they hear that the U.S. Treasury is issuing refunding bonds as opposed to new-money bonds, because they know the former have a largely neutral impact on the market.

In contrast, investors grow tense when a new-money bond is issued because fresh private-sector savings will have to be found to absorb the bond—this money, after all, will be used to build roads and bridges and will not be coming back to the bond market. In other words, new-money bonds can add to upward pressure on interest rates.

But if the maturing government debt is held by the central bank, which will not reinvest the redeemed funds, the funds raised from the private sector by the Treasury via the issuance of refunding bonds do not flow back to the bond market. Instead, they go to the central bank, where they disappear. This, of course, is how the Fed normalizes its balance sheet by absorbing excess liquidity in the market. That means these refunding bonds—despite their name—have the same impact on interest rates as new-money bonds. In other words, they exert the same upward pressure on interest rates as if the central bank had sold its bond holdings directly on the market.

The Fed Tackled the QE Exit Problem Head-On

On June 14, 2017, the Fed announced it would tackle this difficult issue of unwinding QE, now dubbed quantitative tightening (QT), head-on with a concrete plan. Under this scheme, the Fed would initially stop reinvesting $6 billion a month in Treasury securities and $4 billion a month in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), raising those amounts by $6 billion and $4 billion every three months until they reached $30 billion and $20 billion, respectively. From that point on, the Fed would continue not reinvesting $50 billion a month until the level of excess reserves in the banking system had been brought down to a desirable level.

Figure 6.7 shows a projection for the amount of reserves remaining in the market under the Fed's June 2017 schedule. In making this projection, it was assumed that required reserves (the heavy black line) would continue to grow along the trend lines established between January 2015 and May 2017. Although the Fed had not announced what level of reserves would ultimately be appropriate, the June 2017 schedule indicated that excess reserves in the U.S. banking system (as defined at that time) would have been totally removed by July 2021, or 46 months after the start of QT.

FIGURE 6.7 Balance Sheet Normalization Envisioned by the Fed in 2017

Notes: Reserve requirement has been suspended since March 2020, but for the above calculation, it is assumed that the requirement that was in effect in February 2020 remains in force.

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on FRB data; estimates by Nomura Research Institute

Chair Yellen, who started QT, said at her press conference on June 14, 2017: “My hope and expectation is that … this is something that will just run quietly in the background over a number of years, leading to a reduction in the size of our balance sheet.”7 She quickly repeated the phrase “something that runs quietly in the background” and compared the process to watching paint dry in order to re-direct the market’s attention away from the QT. While this is naturally what the Fed would like to see happen, there are a number of potential problems.

The Fed commenced QT in October 2017, which marks the start of the U.S. government's 2018 fiscal year. Figure 6.8 shows the amount of additional private savings that would be required under the Fed's plan to discontinue its reinvestments. The required funds from the private sector amounted to some $300 billion in FY2018 and to $600 billion in both FY2019 and FY2020. The $600 billion figure is roughly equal to the entire federal budget deficit for FY2017. In other words, removing QE in those two years was to have the same impact on interest rates as doubling the 2016 federal deficit.

FIGURE 6.8 Additional Private Savings Required to Offset the Fed's 2017 Quantitative Tightening

Notes: U.S. fiscal accounting year runs from October to following September. MBS = mortgage backed securities.

Source: Nomura Research Institute

It is difficult to describe the likely hit to bond market supply/demand from an effective doubling of the fiscal deficit as “just running quietly in the background.” Even with a shock absorber already in place, this process is likely to put upward pressure on interest rates and may even lead to a steep drop in bond prices. But if QT did run quietly in the background, that would also mean the original QE had had no real impact on the market or the economy.

In spite of these concerns, the QT that commenced in October 2017 went relatively smoothly, proving that the original QE had not been all that effective. And it was ineffective because the U.S. private sector was a large net saver throughout this period. In other words, very few individuals and businesses actually borrowed those funds to increase consumption and investment. Many bond market participants apparently also failed to notice that some of the refunding bonds sold by the Treasury were refunding bonds in name only. Inflows of capital from abroad probably helped as well.

QT came to an abrupt halt when a forecasting error at the New York Fed open market desk on September 17, 2019, caused short-term interest rates to spike.8 Although this accident probably had little to do with QT itself,9 the Fed stopped the process just to be on the safe side. The Fed also reversed the normalization of interest rates and lowered rates twice when signs of weakness in the economy appeared in the second half of 2019.

The advent of the pandemic recession a few months later forced the Fed to reverse course by bringing interest rates back down to zero and restarting the massive QE program, as noted at the beginning of this chapter. But the Fed's sustained QE during the pandemic made the eventual normalization of monetary policy that much more challenging.

No Theoretical Consensus on How to Wind Down QE

Another challenge for central banks normalizing monetary policy is that the economists who encouraged them to adopt QE never provided any theoretical framework indicating how these policies should be wound down. As a result, there is no consensus among academics, market participants, or the authorities on what conditions should be satisfied before starting to unwind QE or at what pace it should be wound down.

The complete absence of a theoretical framework means any decision to exit the policy will almost certainly be criticized in hindsight by academics, market participants, and authorities as being either too early or too late. And this pushback actually happened inside the Fed with its introduction of a “new approach” in August 2020 (this is discussed a bit later).

With no theory to guide the timing of this move, the real question for central bank officials is whether they would prefer to be criticized for being too early or too late ten years from now. All indications up to August 2020 suggest that the Fed decided that, if it is going to be criticized no matter what it does, it would rather err on the side of being too early. The loss function in this case is that a premature exit will result in a more gradual subsequent recovery, but an exit that is too late could cause the economy to overheat and asset bubbles to form, forcing the Fed to engage in an abrupt tightening that could plunge the U.S. economy back into a 2008-like balance sheet recession.

This preference for being too early is fully reflected in the Fed's 2013 decision to begin tapering QE when inflation (measured by the core personal consumption expenditures deflator) was running at just 1.1 percent, and to carry out its first rate hike in 2015, when the inflation rate was only 1.3 percent. The subsequent eight rate hikes were also implemented when inflation was less than 2 percent. These actions indicated that 2 percent was the upper limit on inflation and underscored how afraid the Fed had been of falling behind the curve on inflation, at least until August 2020.

Symmetric Inflation Targets Are Both Ineffective and Dangerous

But in the midst of the pandemic recession in August 2020, the Fed introduced a “symmetric” inflation target based on a “new approach,” whereby it would not immediately tighten monetary policy even if the inflation rate hit 2 percent. This new forward guidance, which suggested the Fed was now willing to err in favor of being too late, seemed to be a response to the dire economic straits the United States faced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Criticism by orthodox economists unhappy with the Fed's continued failure to reach its own 2-percent inflation target may also have played a role in the switch.

But the Fed was failing to reach the target not because it had the wrong policy, but because the economy was fundamentally in Case 3, which is characterized by a lack of borrowers. This shortage of borrowers, in turn, originates from balance sheet problems or inferior returns on capital. These are issues the central bank has little control over. In other words, the announcement of a symmetric target was unlikely to increase borrowing because that was not where the problem lay.

When the inflation rate moved sharply higher in 2021, the Fed scuttled the symmetric target and moved to normalize monetary policy. The fact that bank lending had picked up meaningfully in the fourth quarter of 2021 probably added to the Fed's inflation concerns. U.S. bank lending expanded at a double-digit annualized pace starting in the fourth quarter of 2021 (Figure 6.9). After a short slowdown at year-end due most likely to the spread of the Omicron variant, loan growth has picked up again in the new year, suggesting that U.S. borrowers may be coming back.

As noted earlier, the Fed had to shift its stance because if bond market participants viewed it as having fallen behind the curve on inflation, they would sell bonds to protect themselves from inflation. The resulting crash in bond prices and surge in yields would not only slow down the economy but might also crash the asset market. This would be the “big mess” scenario that Fischer was trying to avoid back in 2016. Realizing this risk, Chairman Powell jettisoned the “new approach” and started normalizing monetary policy in November 2021 in the face of a rapidly increasing inflation rate.

FIGURE 6.9 Credit Creation in the United States Increasing Starting in Q4 2021 Loans and leases at U.S. commercial banks

Note: Numbers in the graph correspond to numbers shown in Figure 2.12.

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on FRB, “H.8 Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the United States”

Post-2022 QT Clearly Framed as Inflation-Fighting Tool

In this new round of normalization, it is worth noting that the QT has been framed very differently. At his March 16, 2022, press conference, Chairman Powell was asked whether the Fed is already behind the curve on inflation, that raising rates by a quarter-point at each FOMC meeting would be enough to curb a consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate of 7.9 percent. One reporter even added that the last time CPI inflation had been at 7.9 percent, in July 1981, the Fed's policy rate was 19.2 percent.

Chairman Powell responded to such concerns by noting that this time the Fed would not only raise rates but would also engage in QT early on and urging reporters to keep that in mind. These remarks indicate that the Fed, after falling behind the curve on inflation in terms of interest rates, is trying to make up for that delay by moving quickly ahead with QT. In other words, the QT is now front and center of the monetary normalization process.

He then added that while the pace of QT would be faster this time than in October 2017, the method used would be similar (“familiar”). In fact, he used the word familiar three times in a row. This is an indication that the Fed is hoping to minimize the rise in long-term interest rates by taking the same approach to QT as it did last time—an approach that the bond market is accustomed to.

But the last experiment with quantitative tightening was conducted preemptively at a time when private-sector borrowing demand was weak and inflation was subdued, which meant there was little reason why long-term interest rates should rise. The Fed also discouraged the market from paying attention to QT.

This time, in contrast, inflation is already running high, and private-sector borrowing demand is starting to exhibit sharp growth, perhaps in response to the fall in real interest rates deep into the negative range as a result of sharp increases in inflation rates. The Fed is also asking the market to pay more attention to the QT which will be implemented at a much faster pace than the previous QT. In other words, many of those factors that kept long-term rates low during the previous episode of QT are no longer available for the post-2022 QT.

Put differently, central banks that did not pursue QE could play around with a symmetric target for a while because there were only minuscule excess reserves in the banking system and the probability of a sudden explosion in credit creation was low. The three lines in Figures 2.12 to 2.14 and 2.17 all moved together before Lehman's collapse because excess reserves in the banking system were minimal and liquidity provided by the central bank (i.e., the monetary base) served as a constraint on the growth of the money supply and credit. Indeed, the most famous battle against inflation in the United States, led by Paul Volcker in October 1979, was successful precisely because the Fed tightened the supply of liquidity, which forced short-term interest rates as high as 22 percent.

But central banks that implemented QE do not have the luxury to wait. With so much excess reserves in the banking system, there is no longer any constraint on credit creation when borrowers return. That means they can rein in inflation only with higher interest rates because the option of limiting reserves does not exist. To avoid what Yellen called an “abrupt tightening,” which has the potential to push bond yields sky-high, central banks that unleashed QE must normalize monetary policy before credit creation gets underway in earnest.

“We Are All Japanese Now”

What exactly is the Fed's “new approach”? From the tone of Chairman Powell's earlier speeches, it appears that many at the Fed felt it had been a mistake to begin normalizing monetary policy in December 2015 and that this approach had led to unnecessary economic weakness and the failure to reach the 2-percent inflation target. For example, Fed Governor Lael Brainard said on June 1, 2021, that “in the previous monetary policy framework, the customary preemptive tightening based on the outlook to head off concerns about future high inflation likely curtailed critical employment opportunities for many Americans and embedded persistently below-target inflation.”10

The proponents of this new approach with a symmetric target are basically saying that, if the public's pre-1979 inflationary mindset could be eradicated with drastic monetary tightening, it should be possible to extinguish today's deflationary mindset, along with the economic weakness it fostered, by allowing the economy to experience high enough inflation for long enough. In other words, instead of focusing on the balance sheet problems and pursued economy issues that led to deflationary conditions in the first place, they are saying the economy will recover if only the public's deflationary sentiment can be eliminated.

Interestingly, the ECB came to the same conclusion when it revised monetary policy in July 2021 following an 18-month review. Key changes included a pledge to ease monetary policy forcefully when inflation or interest rates approach zero, the replacement of the existing inflation target of “below, but close to, 2 percent” with a symmetric target that pays equal attention to readings falling above and below 2 percent, and a pledge to refrain from preemptive inflation-fighting policies.

These new monetary policy approaches adopted by the Fed and the ECB are analogous to BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda's “bazooka” policy, unveiled in 2013, in which he repeatedly declared the bank would not consider normalizing monetary policy until the rate of inflation was consistently above 2 percent. In that sense, the Fed and the ECB belatedly joined the BOJ to create a world in which “We are all Japanese now.”

The fact that consumer confidence had dropped to a 10-year low late in 2021 with the return of inflation (albeit supply-driven inflation) and that long-term interest rates also started moving higher suggests there are serious problems with the argument presented above. The first is that proponents of this view believe central banks can affect people's expectations and behavior without policy makers acting to address balance sheet problems or the inferior returns on capital that have led to excess savings in the private sector. Although this view is held by many economists, the evidence provided in earlier chapters suggests it is little more than wishful thinking.

The second problem, which became alarmingly clear with the onset of inflation in 2021, is that the new approach strips the central bank of its inflation-fighting credentials. Indeed, central banks that implemented negative interest rates, massive QE, and symmetric inflation targets were all trying to establish themselves as deflation fighters. Many prominent academic economists—including Paul Krugman, a Nobel laureate—have also argued that “the central bank needs to credibly promise to be irresponsible”11 so that more people will expect inflation, resulting in lower expected real interest rates. The statement from Governor Brainard previously presented also highlights a belief that the Fed's earlier practice of trying to suppress inflation in advance—that is, its “inflation-fighting” stance—had been a mistake.

When inflation arrived, central banks realized they had zero credibility as inflation fighters because they have been combating deflation for the last twelve years. But the combination of high inflation and an absence of central bank with inflation-fighting credentials had the potential to trigger a bond market sell-off and a surge in long-term interest rates that would be disastrous for the economy. Chairman Powell's sudden hawkish shift on inflation in late 2021 was probably based on the view that the Fed needed to emphasize its determination to prevent such a scenario by reinventing itself as an inflation fighter.

The dramatic shift in the Fed's stance also served to highlight the uselessness of a symmetric inflation target. The idea that having a long enough period of high inflation will rid people of their deflationary mindset ignores the risk that such a policy may bring about a bond market crash. And if the bond market crashes, the economy may go down with it. Fortunately, Chairman Powell realized this danger and changed course before it happened, but the risk remains depending on what happens to inflation.

The third problem with the new approach concerns the question of how much stronger the U.S. economy12 would be if the Fed had not begun normalizing policy in 2015. The Chicago Fed's national financial conditions index largely shrugged off the nine rate hikes that began in 2015 and the QT that commenced in 2017 (see circled portion at lower right in Figure 4.3). In fact, it indicated that financial conditions remained highly accommodative and were not weighing on the economy up until the pandemic. The U.S. unemployment rate also fell steadily, from 5.0 percent in December 2015 to a 50-year low of 3.5 percent in February 2020, and stock prices continued to post new all-time highs during this period.

Financial conditions failed to tighten because the U.S. economy has been in Case 3, and businesses and households were both large net savers because they were still repairing their balance sheets. This also means that when businesses and households are repairing their balance sheets, they do not respond to movements in interest rates, whether up or down. That, in turn, implies that U.S. economic activity probably would not have been any stronger if the Fed had kept policy accommodative in 2015 and beyond. The lack of borrowers in the real economy also forced fund managers at financial institutions to continue investing excess private savings in existing assets, leading to rising asset prices.

This conclusion can also be inferred from the experiences of the BOJ and the ECB. Not only have they not even mentioned the possibility of normalizing monetary policy, but they actually took their policy rates into negative territory. Moreover, the BOJ has been implementing what the Fed would call a symmetric inflation target since 2013.

Nevertheless, private-sector borrowing in both regions experienced almost no pickup in growth during this period (Figures 2.13 and 2.17), indicating that their private sectors were not responding to interest rates either. The continued stagnation of these economies suggests that, contrary to Governor Brainard's previous comment, the U.S. economy probably would not have been any stronger if the Fed had chosen not to normalize policy starting in 2015.

The fourth problem with the new approach concerns the costs that delaying policy normalization would have had in the United States. Asset price bubbles would probably have grown even larger with continued zero interest rates and ever-greater market liquidity. The Fed's quantitative tightening drained $660 billion in liquidity from the market between October 2017 and September 2019. If this liquidity had stayed in the market, it would most likely have been used to purchase existing assets given the shortage of borrowers in the real economy.

Even though the Fed began normalizing monetary policy in 2015, stock prices have continued to post fresh all-time highs, and commercial real estate prices are now 68 percent higher than they were at the previous peak in 2007. Both would probably be even higher today without the post-2015 normalization of policy. With rising house prices already a major driver of the inequality that has divided U.S. society, few would view further expansion of the housing bubble as a desirable policy outcome.

Housing prices are also becoming a major social issue in the Eurozone. When the ECB talked to people from different walks of life during its 18-month review of monetary policy,13 according to President Christine Lagarde, the concern over house prices was so great that the Bank had to promise to pay greater attention to the cost of housing when making monetary policy decisions.

Bubbles Create Both Financial and Macroeconomic Problems When They Burst

Yet mid-2021 comments by senior Fed officials suggest they are surprisingly unconcerned about the potential for the bubble to burst. They argue that the risk of another Lehman-like event is low because U.S. financial institutions are much better capitalized than they were in 2008.

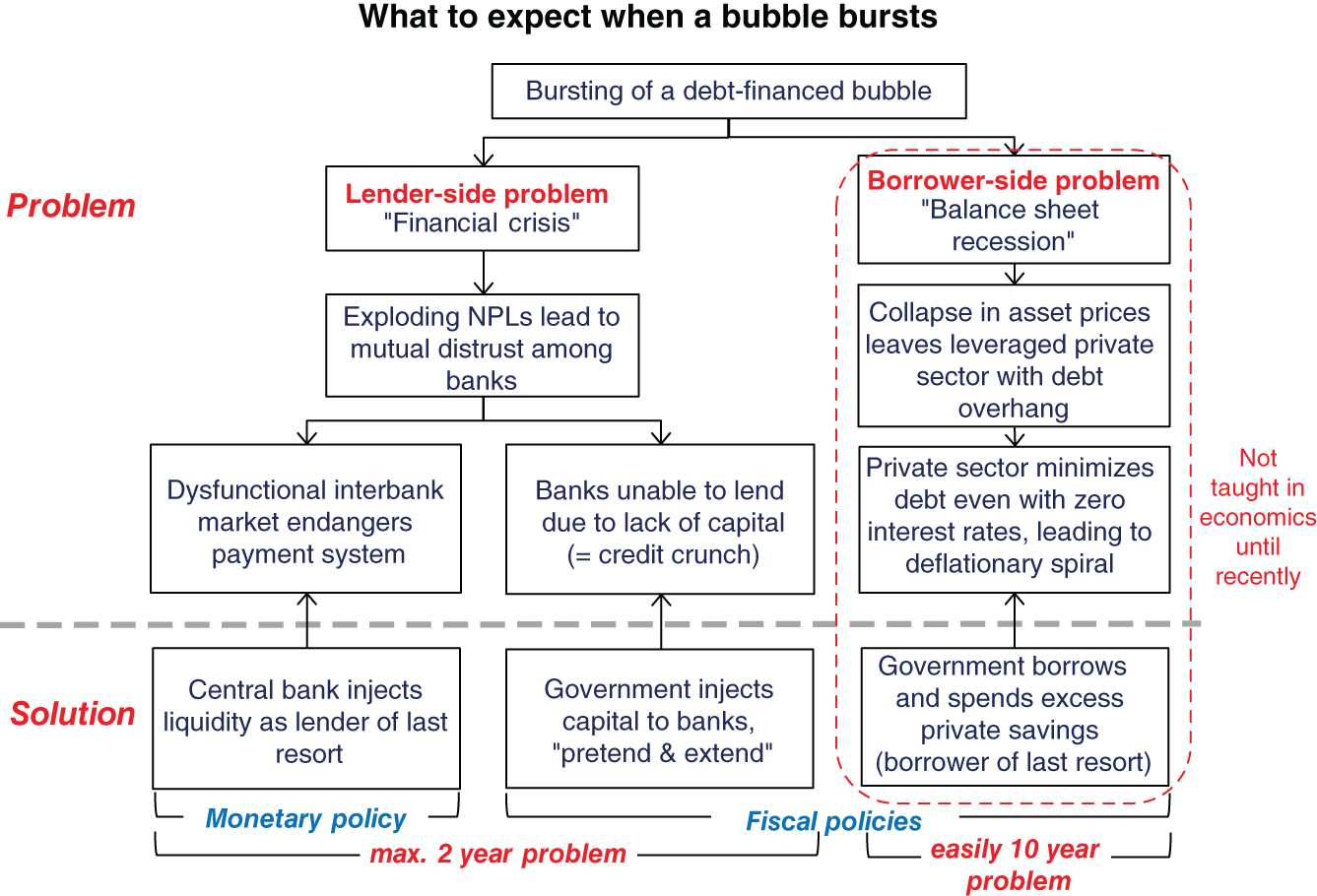

There is no question that U.S. banks are better capitalized now than in 2008. But when a bubble bursts, it creates two problems, as is noted in Figure 6.10. One is the financial crisis triggered when financial institutions that participated in the boom suffer capital impairments and begin to distrust each other. The other is the balance sheet recession that results when asset prices plunge but the debt used to acquire them remains, forcing an over-indebted private sector to begin paying down debt. The former is a financial problem related to lenders, while the latter is a macroeconomic problem related to borrowers. And the central bank bears responsibility for both.

FIGURE 6.10 Well-Capitalized Banks Will Not Prevent Balance Sheet Recession

Financial Crises Can Be Contained in about Two Years If Properly Addressed

The 2008 GFC created a great deal of financial turmoil: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, Merrill Lynch was rescued by Bank of America, Morgan Stanley needed help from Mitsubishi UFJ, and the economy struggled under a credit crunch. Nevertheless, the seize-up in financial markets—as indicated by the sharp increase in the Chicago Fed's financial conditions index triggered by the Lehman shock—had largely subsided by 2010, a little more than two years later (Figure 4.3). Growth in banks' assets and liabilities also began to normalize in about two years (Figure 8.11), and conditions in the interbank market returned to normal around the same time (Figure 8.12).

This was because the authorities responded appropriately with the measures prescribed for Case 2 in Chapter 1. The U.S. government, for example, injected capital via the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in October 2008 and allowed banks to roll over impaired commercial real estate loans with the Policy Statement on Prudent Commercial Real Estate Loan Workout (“pretend and extend”) in October 2009.

In Japan, the government responded to the nationwide banking crisis in 1997, which was triggered by the failure of Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, by injecting capital into the banks and offering generous loan guarantees to borrowers. The debilitating credit crunch that was causing so much economic pain began to ease about two years later, in 1999 (see Figures 6.2 and 8.7). The point is that even a major financial crisis, which is a lender-side problem, can be contained in about two years if appropriate policies are implemented.

Recovery from Balance Sheet Recessions Takes Far Longer than Two Years

The same cannot be said for balance sheet recessions, which involve borrower-side problems. Both Europe and the United States suffered balance sheet recessions lasting nearly a decade after Lehman went under. Economic growth and inflation remained depressed even though the Fed and the ECB took interest rates to zero and engaged in truly astronomical amounts of quantitative easing.

As is explained in Chapters 1 and 2, a key reason for this is that individual households and businesses are all behaving responsibly by trying to restore their financial health, and there is no way they can do anything else. But when everyone deleverages at the same time, it creates the unintended consequence (i.e., the fallacy-of-composition problem) of a disappearance of borrowers and triggers a deflationary spiral.

Both Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and Vice Chairwoman Janet Yellen were cognizant of this danger and managed to save the economy by repeatedly warning Congress that the United States would fall off a “fiscal cliff” if it pursued fiscal consolidation. In contrast, policy makers in the Eurozone were ignorant of this danger and proceeded to push their economies off the cliff. In the ensuing collapse, Spain's unemployment rate surged to 26 percent and Greece's GDP plunged by 27 percent.

These experiences indicate that a balance sheet recession will continue until the majority of people have finished repairing their balance sheets, a process that can easily take a decade because of the fallacy-of-composition problem that makes balance sheet repairs doubly difficult. Having banks that are well capitalized increases the probability that the two-year lender-side problems will be relatively mild, but they do nothing to mitigate the 10-year borrower-side problems, which can be extremely painful.

Calling the Post-2008 Economic Downturn the GFC Was a Mistake

Unfortunately, the economics profession was completely oblivious to the concept of a balance sheet recession when Lehman Brothers failed and the GFC ensued in 2008. Even today, few understand the dangers inherent in such a recession.

In retrospect, it was a major mistake to have dubbed the post-2008 economic downturn the “global financial crisis,” or GFC. Even though the long and painful recession had some elements of a financial crisis during the first two years, the far bigger problem was that millions of household and business balance sheets were underwater and required nearly a decade to repair. But because it was called the GFC, most commentators looked only at what was happening in the financial sector and ignored what was happening to the balance sheets of households and businesses. Those businesses and individuals with impaired balance sheets also had every reason to hide that fact until their financial health is restored, as is mentioned in Chapter 2. The fact that most commentators in academia and the markets in 2008 were totally unaware of the ailment called balance sheet recession made them pay even less attention to the impaired balance sheets of the private sector.

As is noted in Chapter 1, it was Mikhail Gorbachev who said, “You cannot solve the problem until you call it by its right name.” The post-2008 debacle should have been called the Great Balance Sheet Recession, or GBSR, instead of the GFC. But because it was dubbed the GFC, most people never paid attention to the most important driver of the recession. That has left open the possibility that the world will repeat the mistake of underestimating the devastating impact of balance sheet repairs by the private sector after a bubble bursts.

Chairman Powell's comment that we need not worry too much about elevated asset prices because banks are now better capitalized than in 2008 reflects this sort of complacency. Both house prices and commercial real estate prices (Figure 4.7) have now risen well beyond their previous bubble peaks. If these bubbles burst, the U.S. economy will be back to square one, facing years of painful balance sheet recession all over again.

The ECB's Policy Review Was Far from Adequate

European house prices are also far above the bubble-era highs in many parts of the continent (Figure 2.4). In spite of the growing danger that another bubble is in the making, the ECB policy review unveiled in July 2021 did not even mention that private-sector balance sheet problems were a key reason why the Eurozone economy has been depressed since 2008 (this point is explained further in Chapter 7). Instead, it argued that the slump was attributable to a lower real equilibrium interest rate resulting from “a decline in productivity growth, demographic factors and persistently higher demand for safe and liquid assets in the wake of the global financial crisis.”14 Here, “real equilibrium interest rate” refers to the rate of interest that will allow policy makers to consistently achieve their inflation target.