CHAPTER 5

Economic Growth and Challenges of Remaining an Advanced Country

Over-Stretching Is Required for Economic Growth

The preceding four chapters are all about how an economy could stagnate, sometimes for an extended period, when it is in Cases 3 and 4. This chapter discusses the opposite case, the drivers of economic growth. Not surprisingly, economic growth is highly relevant to an economy in Case 1 or 2.

Much has been written about economic growth since the days of Thomas Malthus. However, the recent emphasis on productivity and demographics by economists seeking to explain growth has placed the growth debate on the misleading path.

At the most fundamental level, someone must spend more than they earn for an economy to grow. If businesses and households behave prudently and spend only what they earn in each period, the economy may be stable, but it will not grow. For it to expand, some entities must over-stretch themselves—either by borrowing money or drawing down savings.

A business will do so if it finds an attractive investment opportunity that seems to offer returns that are higher than the borrowing costs. Similarly, a household might borrow money or reduce its savings if it finds an item that it feels it cannot live without. It should be noted that business and household borrowings to purchase existing assets do not count here—these transactions only result in a change of ownership and do not add to GDP.

Economic growth, therefore, requires either (1) a continuous supply of attractive investment opportunities capable of persuading companies to borrow money or (2) a continuous flow of new and exciting products that consumers want to buy, even if that means reducing savings or going into debt. Many factors influence the availability of investment opportunities and “must have” products, and demographics and productivity considerations are just two of them.

A government can also over-stretch by borrowing and spending money to increase economic growth. So-called pump-priming via fiscal stimulus is an attempt by the government to over-stretch itself in order to put a weak economy back on a growth path. Government investment in social infrastructure may also give businesses more reasons to over-stretch and thereby spur growth.

But unless the economy is in Case 3 or 4, government over-stretching cannot be relied on for too long because it can crowd out private-sector investments and increase the burden on future taxpayers. As government investments tend to be less efficient than the private-sector equivalent, economic growth often slows when the former start to crowd out the latter.

If attractive investment opportunities and “must-have” products are plentiful, there will be no shortage of private-sector borrowers, and the economy is in Case 1 or 2. When that is the case, policy makers should rely more on monetary policy because it will be highly effective in steering the economy. An overreliance on fiscal policy under such circumstances will only result in the crowding-out of private-sector investments and a general misallocation of resources. In other words, when the economy is in either of those two cases, standard textbook theory regarding the undesirability of fiscal policy and the desirability of monetary policy applies.

Consumer- and Business-Driven Economic Growth

For the economy to continue growing, there must be good reasons for businesses and households to over-stretch themselves on a sustained basis. For consumer-driven growth to continue, the recurrent emergence of new “must-have” products is necessary.

The problem is that it is difficult to forecast when such blockbuster products might emerge, because predicting the inventions and innovations that lead to such products has proved to be notoriously difficult. It is also hard to foresee what will appeal to consumers' rapidly changing tastes. This uncertainty is particularly acute in the developed world, where households already own most of life's necessities.

In contrast, business-driven growth is more robust because companies are always under pressure from shareholders to expand their operations and generate more profits. It is also businesses that create the products that consumers find irresistible. While there is no guarantee that businesses will hit upon such products or find other investment opportunities, they tend to be more dependable drivers of economic growth than fickle consumers.

Positive Fallacy-of-Composition during Golden Era

During the golden era, when businesses are faced with a surfeit of domestic investment opportunities and the purchasing power of consumers is growing rapidly, as is explained in Figure 3.1 in Chapter 3, corporate decisions to over-stretch by investing in capacity- and productivity-enhancing equipment are not difficult to make. That, in turn, often creates a positive fallacy of composition that serves to accelerate economic growth.

Because one person's expenditures are another's income, if all households and businesses “live beyond their means” and begin consuming and investing more, their incomes will increase by an amount equal to the growth in expenditures. For example, if everyone decides to over-stretch by spending 10 percent more than they earn, either by dis-saving or by borrowing money, their incomes will also increase by 10 percent because everyone else will be spending 10 percent more than before.

With incomes up by 10 percent, the initial decision to over-stretch no longer appears especially reckless relative to current incomes—this is what might be called the “paradox of dis-saving.” This positive fallacy of composition with rapidly increasing incomes may lead to an even greater willingness to consume and invest on the part of consumers and businesses. This virtuous growth cycle is observed frequently during the golden era and is another example of one plus one not equaling two in macroeconomics. The growth momentum created by this positive feedback loop is also one reason why economic growth is taken for granted during the golden era.

A vast number of Japanese households in the late 1950s sought to acquire sanshu-no-jingi, or the “three sacred items”—a black-and-white television set, a refrigerator, and a washing machine—even if they had to borrow money to do so. Those purchases added significantly to the Japanese economy's rapid growth during that period. This is the opposite of Keynes's “paradox of thrift”; by collectively living beyond their means, consumers can drive the economy into a virtuous growth cycle. The rapid growth experienced by an economy in a bubble—for example, the surge in Japanese gross domestic product (GDP) before the bubble burst in 1990 (Figure 2.1)—is probably due to this paradox. As long as the paradox is producing positive outcomes, however, most people are happy to go along with it.

For this positive fallacy of composition to continue, there must be sufficient and concurrent growth in savings to draw upon. That is why economies that favor savings will grow faster than those that do not when there are plenty of good reasons for businesses and households to over-stretch themselves. When the economy is in Case 1 or 2, therefore, saving is a virtue, as is noted in Chapter 3.

Two Strategies for Businesses to Follow

While there is no guarantee that there will always be attractive investment opportunities worth borrowing money for, there are basically two growth paths for businesses to follow amid that uncertainty. They can try to develop either new products and services capable of wowing customers (Strategy A) or new ways to supply existing products and services at lower cost (Strategy B).

Strategy A, when successful, will lead to rapid growth not only for the company but also for the economy as a whole by spurring consumer-driven economic growth. If the new product displaces old products, total expenditures in the economy may not increase significantly, apart from the investment required to develop the new product. But chances are high that companies that lost market share to the new entrant will try to regain it by investing in the development and production of near-substitutes. Those investments will add to GDP growth.

On the other hand, this strategy is also risky because predicting profitable inventions and innovations is notoriously difficult, as noted earlier. This strategy may also require access to leading-edge technologies that only a few companies have access to. This strategy is therefore pursued mostly by businesses in the developed world with both the financial strength to take risks and access to the intellectual property rights framework needed to protect newly developed products.

Strategy B, which involves making existing products more cheaply, also provides a powerful motive to borrow and invest for entrepreneurs who believe they have devised a better way to produce existing services and products. Because consumers do not have to over-stretch as much to buy these cheaper products, a company pursuing Strategy B may earn a healthy return on capital by capturing market share quickly.

The emergence of companies offering competitively priced products may also force existing producers to invest more in productivity-enhancing equipment to stay competitive. The resultant over-stretching by rival firms adds to both economic and productivity growth.

Most businesses follow a mixture of Strategy A and Strategy B depending on their product lines. But the main source of growth is likely to be Strategy A in the advanced economies and Strategy B in the emerging economies.

Profit Motive and Productivity

Whether following Strategy A or B, most businesses are constantly on the lookout for ways to increase profitability by enhancing productivity, and they are likely to borrow and invest in machinery and innovations that lead to lower costs and higher profits. Many businesses may also be forced into investing in new equipment to raise productivity just to remain competitive. Those investment expenditures will add to economic growth.

It should be noted, however, that the economy in this case did not grow because of increased productivity. It grew because firms over-stretched themselves in the hope of raising profits when cost-cutting innovations presented themselves. If they did not over-stretch in acquiring the new equipment, their productivity might improve, but the economy would not expand because total expenditures would remain the same. This means the concept of “cash flow management” in post-bubble Japan that is noted in Chapter 2, where companies refuse to borrow money and invest only as much as cash flow will allow, has not been helpful to the country's economic growth.

The preceding discussion also suggests that the profit motive and technological progress in cost-reducing equipment are important drivers of productivity-enhancing investments. Of the two, the importance of the profit motive was amply demonstrated by the persistence of slow economic growth in communist economies where such a motive was absent. Technological progress in cost-cutting equipment, on the other hand, often depends on scientific discoveries and technological innovations that are difficult to forecast, as noted earlier.

Problems with the Concept and Measurement of Productivity

The concept of productivity is also not so straightforward. It has been said for decades that Japan's manufacturing sector is highly productive, but its service sector is not. There is no question that the former is true, but if the latter were also true, Japan should have been flooded with foreign retailers and other service providers that are more productive than their Japanese rivals.

U.S. and European retailers have made numerous attempts over the decades to enter the Japanese market. After all, Japan was the world's second largest consumer market until 2010, when China took away that title. But almost all of these attempts failed, and there is still no meaningful foreign penetration of the Japanese retail market.

The reason for this failure is simple. There is a big difference in the relative factor prices of real estate, energy, and labor between Japan and the West. In Japan, real estate and energy prices are high relative to the cost of labor, whereas the opposite is true in the West. As a result, a typical Japanese retailer will try to use as little real estate and energy as possible relative to workers to maximize profits, whereas a Western retailer will take the opposite tack. Japanese stores therefore tend to be smaller establishments staffed by many employees, while Western stores are generally huge, well-lit establishments staffed by only a few people.

When revenues are divided by the number of workers, Japanese stores are naturally outperformed by Western establishments. But this so-called “labor productivity” figure is meaningless without considering the productivity figures for the floor space and energy used, where Japan comes out looking significantly better than the West.

Western retailers who did not understand this point and operated stores in Japan the same way they did at home lost a great deal of money before eventually having to leave. Any attempt to raise so-called “labor productivity” in Japan is futile unless relative factor prices in the country are the same as in the West.

This also implies that actual labor productivity should be measured per unit of capital—including land. But measuring the amount of capital available to each worker is extremely difficult, if not impossible. There are, however, some anecdotal cross-country comparisons.

A traveling Australian entertainment group has been performing “Thomas the Tank Engine” for children around the world with the same stage props for years. The props are set up in theaters in each country by the same number of young part-time workers. The Australian manager of the group told the author's son, who was one of the part-time workers in Japan, that in any other country, setting up the props takes a minimum of four hours, and often six hours or more. But in Japan, he said, it never takes more than two hours even though different workers are involved each year. This anecdote suggests young Japanese part-time workers may be more productive than their peers elsewhere.

It could be argued that cross-country productivity comparisons should be made based on total factor productivity instead of labor productivity. This is easier said than done, since it may require adding apples and oranges when different factors of production are involved.

One way to get around this problem in comparing retail sector productivity is to examine final selling prices across countries, since retailers with higher total factor productivity should be able to sell products at lower prices.

The Big Mac index compiled by the Economist magazine is useful in this regard because the quality of Big Macs is the same everywhere in the world (see Figure 9.3 in Chapter 9). Although the original objective of the index was to determine the over- and under-valuation of currencies on a purchasing power parity basis, it is interesting to note that in Japan, which has the same per capita GDP as Europe, Big Macs are sold at a much lower price than in Europe, even though Japan imports almost all of its ingredients from abroad. This suggests either that the yen is undervalued, or that the Japanese operation has a much higher total factor productivity than the European operations.

It was not always this way. Prices in Japan used to be much higher than the international norm, and Tokyo was consistently voted the world's most expensive city well into the 1990s. The gap in prices was so bad that there was even a Japanese word, naigai-kakakusa, to describe the huge disparity between domestic and international prices. The gulf was so wide that the author used to buy everything from daily necessities to motor oil in the United States and bring them back to Tokyo in suitcases.

But this all changed when the shock of an incredibly strong yen—the Japanese currency climbed to 79.75 yen/dollar in April 19951—finally kicked open the domestic market to imports. The relentless competition among domestic retail establishments that followed made Japan one of the cheapest places to dine and shop in the developed world.

Japan now has over 4,000 so-called 100-yen shops offering everything from quality household wares to stationary items from around the world for 100 yen (about $.80) each. Many of these stores are selling goods at the lowest prices seen anywhere in the world. The fact that they are often sitting on some of the most expensive real estate in the world suggests that total factor productivity is high. Since these shops have appeared, no one in Japan talks about naigai-kakakusa anymore.

Profitability and Physical Productivity

Another problem with productivity is that it is often confused with profitability. In the mid-1980s, many Japanese companies borrowed and invested heavily in the latest equipment and factories to make themselves even more competitive. The exchange rate at the time was 240 yen to the dollar. But when those factories came on line in the late 1980s, the exchange rate had fallen to 120 yen to the dollar, reflecting a stronger yen. The companies that had made these investments were badly hurt, and economic growth slowed.

Japanese companies enjoyed higher physical productivity with their newer equipment and factories, but capacity utilization and profitability were far lower. When the exchange rate went to 80 yen to the dollar in the mid-1990s, many of these companies were referred to as “zombies” because of their earlier over-stretching, even though their physical productivity was still second to none.

Many observers who argue that Japanese GDP growth declined because of reduced productivity growth are mistaking profitability for productivity. It is the decline in profitable investment opportunities due to the strong yen that has weighed on investment (i.e., over-stretching) and GDP growth. Investment also declined after the bubble burst in 1990 because so many companies faced balance sheet problems, and productivity growth slowed because there was less investment.

As is noted in Chapter 4, productivity growth has recently slowed in almost all advanced countries because they have become pursued economies, with lower returns on capital than are available in emerging markets. With shareholders clamoring for higher returns on capital, it has become difficult for companies in these countries to justify investing in less profitable projects at home. That, in turn, has lowered both economic and productivity growth in the advanced nations.

Higher Productivity Does Not Necessarily Lead to Higher Wages in Pursued Economies

Even if businesses invest in productivity-enhancing equipment at home in a pursued era, such investments do not increase the wages or purchasing power of workers the way they did during the golden era. U.S. President Joe Biden noted during his 2020 election campaign that U.S. productivity had risen 70 percent between 1979 and 2018 while wages had grown only 12 percent in real terms. This decoupling of wages and productivity growth has much to do with the fact that the United States and other advanced economies are now in the pursued era.

The Western economies until the 1980s, and Japan until the 1990s, were in a golden era where attractive domestic investment opportunities were plentiful but the supply of labor was limited. That led to annual increases in wages as the expanding economy moved along the upward-sloping labor supply curve from K to P in Figure 3.1. This wage growth was also the key driver of domestic demand because it increased workers' purchasing power.

Businesses facing rising wages as well as greater demand for their products expanded investment both to boost productivity (to remain competitive) and to expand capacity (to meet additional demand). Wage growth and productivity growth therefore moved together, with the former driving the latter.

For the last 30 years, however, businesses in advanced countries have realized that the return on capital is higher in low-wage emerging markets than in their high-wage home markets, and they have shifted their investment destinations accordingly. Instead of paying higher wages at home, they simply moved production abroad. That has resulted in the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs at home and slower economic growth. The loose domestic labor market conditions that resulted removed the key reason for wages to rise. Consequently, companies are no longer forced to enhance productivity to pay ever-increasing wages.

If businesses invest at home in the pursued era, they do so to improve profitability. Even if wages are not rising, there is no reason not to invest in equipment that lowers costs and boosts profitability. The resultant improvements in productivity do not translate into higher wages because wages themselves are determined by the labor market, where conditions are much looser than during the golden era.

During the golden era, labor productivity and wages moved in tandem because it was the rising wages that forced companies to enhance worker productivity. During the pursued era, the benefits of improved productivity brought about by corporate investments go to those who made the investments, not to the workers.

Will Higher Minimum Wage Boost Productivity?

Some have argued that the government should then raise the minimum wage to boost labor productivity. Although rising wages will force some companies to make more productivity-enhancing investments, higher unemployment could also result if the wages are rising because of government decree and not because of tighter labor market conditions.

An attempt to raise the minimum wage in a pursued economy also risks shifting even more investment to emerging economies by further depressing the domestic return on capital. Unlike their predecessors in the golden era, many businesses in the pursued era have production facilities located around the world. That means proposals to raise the minimum wage should be approached carefully inasmuch as they have the potential to further reduce already low domestic returns on capital and create more unemployment.

The point is that businesses do not engage in productivity- or capacity-enhancing investments if they see no money in it. Productivity growth is the result of businesses responding to the emergence of cost-cutting investment opportunities that increase their return on capital. When such opportunities present themselves in the form of technological progress and are acted on by businesses that over-stretch themselves, both economic and productivity growth will accelerate.

Whether that growth benefits labor depends on the tightness of the labor market. That, in turn, is often determined by whether the economy is in the golden era or the pursued era. In the golden era, the macroeconomic tide originating from a surfeit of domestic investment opportunities prompts businesses to expand, increasing demand for labor in a tight labor market, thereby raising all wages. In the pursued era, when returns on capital are higher abroad than at home, there is unlikely to be a macroeconomic tide that lifts all wages. Instead, individual workers must enhance their own productivity by learning new skills if they want to increase their income. Businesses will continue to invest more to boost productivity, but the resultant increase in productivity does not often lead to higher wages in a much looser labor market of the pursued era.

Export-Driven Economic Growth Faces Fewer Hurdles

For many industries in the developed world, significantly cheaper labor costs in the emerging economies eliminate the option of pursuing Strategy B at home. Barring revolutionary discoveries or innovations that drastically improve domestic productivity, it simply does not make sense for them to continue with Strategy B. That is why they became pursued economies in the first place, and why so many companies in these countries are forced to pursue the more difficult Strategy A.

For businesses located in the emerging world, on the other hand, wage levels often make the pursuit of Strategy B highly attractive. For instance, wages in Japan and China were far lower than those in the West when the two countries first entered the global market in the 1950s and 1980s, respectively. All manufacturers had to do was to produce quality products cheaply (which, of course, is not easy), and the products would basically sell themselves in overseas markets.

These less-expensive products sold themselves because there was no need for consumers in importing nations to over-stretch when buying them. On the contrary, consumers in the importing nations were saving money by switching to lower-priced imports, which is the opposite of over-stretching. From the perspective of exporting countries, foreign consumers were doing the over-stretching that helped their exports and economies to grow, but individual consumers in importing countries saw themselves as under-stretching by shifting their purchases to cheaper imports. (The inherent contradiction here is discussed further in Chapter 9, which looks at global trade.)

That means that even if the products themselves are not new and do not “wow” consumers, exporting companies and countries can grow rapidly as long as their products can be priced competitively in overseas markets. Japan and all the other countries that successfully achieved export-led economic growth in the postwar period started out with Strategy B.

Even though most businesses pursue a combination of Strategy A and B depending on the product line, most companies in pursued countries are forced into the riskier and more difficult Strategy A, resulting in slower growth for the economy. Businesses in emerging markets, on the other hand, are either in the pre–Lewis Turning Point (LTP) urbanization era or the post-LTP golden era and tend to pursue the easier, less risky Strategy B, which leads to faster economic growth.

Import-Substitution Model Seldom Sustainable

The emphasis on over-stretching to explain economic growth also helps to explain why the export-driven model of economic growth has been more successful than the import-substitution model pursued by some countries. In the latter case, the captive market provided by protectionist government policies initially boosts the profitability of businesses benefiting from the protection. That prompts them to increase investment at home, accelerating economic growth. But someone in the economy must continuously over-stretch themselves for this growth model to remain viable.

For that to happen, businesses must continuously come up with new and exciting products to wow domestic consumers, something that has proved difficult for underdeveloped local industries requiring government protection. The limited size of the domestic market also leads to correspondingly high production costs, making these products less attractive to consumers. In addition, their high cost limits their appeal to foreign consumers, making it difficult for businesses to pursue Strategy B. In other words, this growth model effectively asks businesses in developing countries to pursue the more difficult Strategy A.

That is why after a promising initial boost to growth, this model has never remained viable for long in any country—although it has been tried by many countries in Latin America and elsewhere in the 1950s and 1960s.

Transparency Is the Greatest Attraction of U.S. Market

The export-driven model of growth does have one requirement that the import-substitution model never had to worry about: access to foreign markets. Before 1945, access to foreign markets was limited for most countries because all nations had erected numerous barriers to trade. Indeed, revenue from tariffs had been a major source of government income for centuries. With many foreign markets effectively closed, most countries had no choice but to pursue the import-substitution model of growth. That, in turn, placed substantial constraints on global economic growth.

All that changed after World War II when the United States introduced a free-trade regime under General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), as is noted in Chapter 4. Even though the concept and practice of free trade had been observed from time to time in the past, the U.S. decision to open its vast domestic market—which accounted for nearly 30 percent of global GDP at the time—was a game-changer.

Japan, realizing the far-reaching implications of the U.S. policy change, placed its best and brightest in exporting industries and started growing rapidly. The Japanese success was soon followed by Taiwan, South Korea, and others. Wartime technological breakthroughs helped, of course, but without free trade it would be difficult to explain the rapid economic growth of countries such as West Germany and Japan, which depended heavily on the U.S. market.

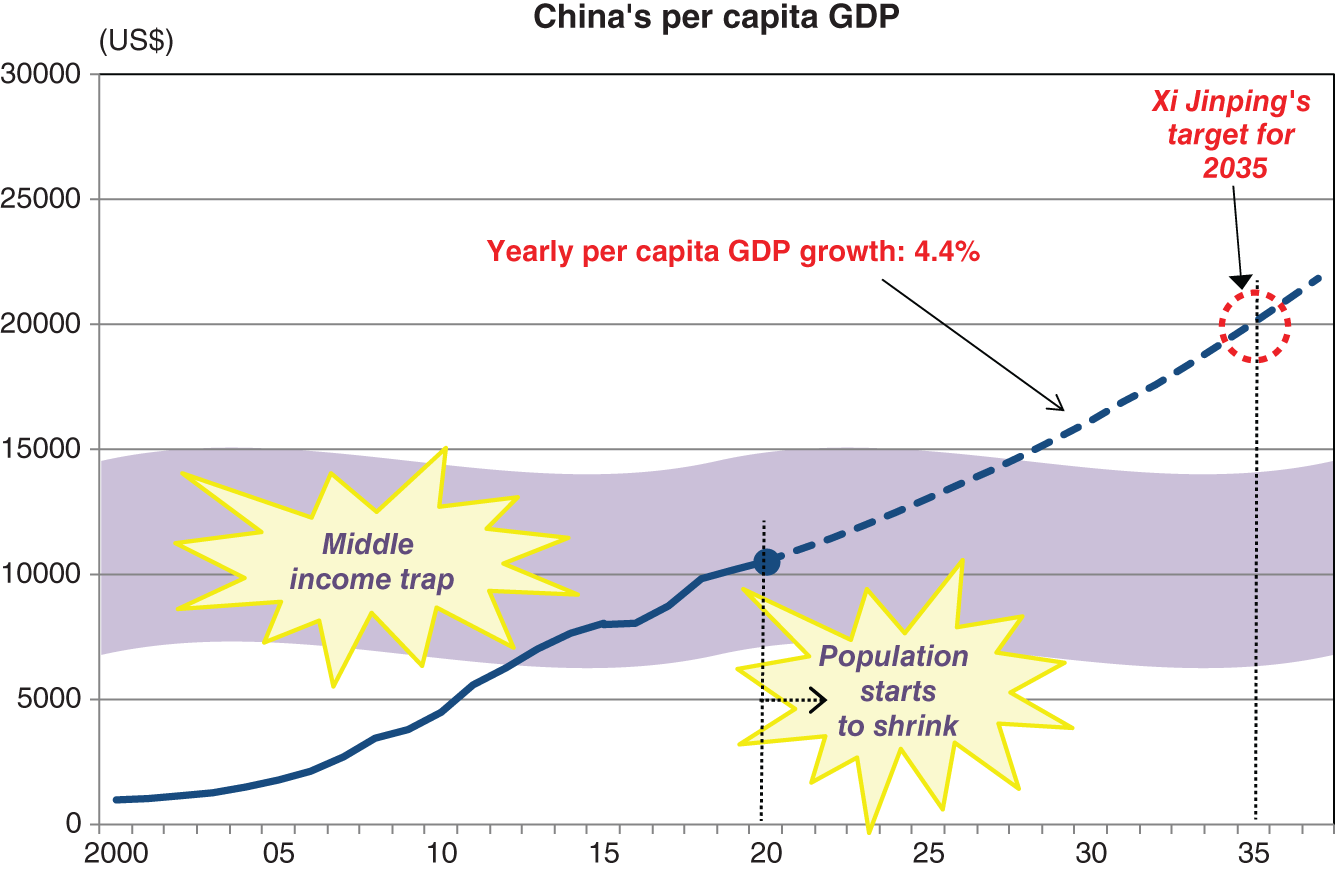

The end of the Cold War in 1990 then allowed Communist and former Communist countries to join the free trade bandwagon. China, with its low labor costs, benefited most. Capitalizing on the U.S.-built free trade regime, China raised its per capita GDP from a paltry $300 in 1978 to over $10,000 in 2019 for 1.4 billion people, representing the greatest burst of economic growth in history. Indeed, all countries that have relied on exports to achieve economic growth after 1945 have done so by tapping into the U.S. market.

The Importance of Recognizing the Source of Over-Stretching

The importance placed on the U.S. market by the Japanese came as a cultural shock to the author when he moved from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to Nomura Research Institute (NRI) in Tokyo in 1984. When forecasting GDP growth, it was typical in the United States to start the exercise by estimating personal consumption, which is the biggest component of U.S. GDP. From there, projections of other, smaller components of GDP such as fixed capital investment and net exports were added to come up with a final figure.

In Japan, which was already the second largest economy in the world, the forecasting exercise at NRI, the oldest, largest, and most influential private think-tank in the country at the time, started with an elaborate forecast of the U.S. economy. Projections for Western Europe were then added to come up with a forecast of Japan's exports. Exports were followed by fixed capital investment, and forecasts of personal consumption and other items came after that. This was in spite of the fact that personal consumption was the biggest single component of Japan's GDP and was far larger than exports.

The Japanese knew that exports were the key driver of growth, and that it was foreigners who were doing the crucial over-stretching. They knew from experience that if exports slumped, other components of GDP would also stagnate. They understood that as far as growth is concerned, where the over-stretching is happening is more important than the size of the sector itself. Even if exports are not the biggest sector, if that is where most of the over-stretching is taking place, then that is where the focus should lie when forecasting overall economic growth.

Even today, the United States remains a crucial market for both developed and developing countries, including Japan, Europe, and China. This is due not only to the size of the U.S. market, but also to its great transparency and the absence of nontariff trade barriers. From a business standpoint, transparency is often as important as—if not more important than—the size of the market itself.

For instance, the nominal GDP of the 27 European Union nations was equal to 73.1 percent of U.S. GDP in 2020, and in the mid-1990s Japanese GDP approached 70 percent of U.S. output. In 2020, China's nominal GDP was 71.2 percent of the U.S. figure.2 However, the companies and countries that would suffer from being shut out of U.S. market far outnumber those that would be hurt by being kept out of the other three markets.

The reason is that the other three markets are less transparent than the United States and therefore require much greater efforts by foreign exporters. The return on capital for marketing efforts in these three markets is therefore lower than in the United States. As a result, many companies do not even try to penetrate the other three markets.

The difficulty of breaking into the Japanese market, for example, was amply demonstrated until quite recently by the existence of many so-called export-only manufacturers in Japan. These companies existed because they could earn a much higher return on capital by concentrating their marketing efforts in more transparent overseas markets—and particularly the U.S. market—instead of trying to crack the more difficult domestic market. This transparency is also why many governments—including those of Japan, China, and Europe—were so eager to conclude a “deal” with former President Donald Trump when he was pushing a protectionist “America First” agenda.

The Middle-Income Trap and Difficulty of Transitioning from Strategy B to Strategy A

Advanced countries at the receiving end of emerging economies' export drive have largely exhausted low-hanging investment (i.e., over-stretching) opportunities at home, and their economic growth has slowed, even though business executives are paid a great deal to identify profitable investment opportunities. The West was shocked when Japan emerged as a fierce competitor in the 1970s, pushing many well-known manufacturers out of business and forcing remaining companies to focus on the more difficult Strategy A.

Japan then experienced a similar shock when the Asian Tigers began chasing it in the 1990s, as did the Asian Tigers themselves when Chinese competition appeared in the 2000s. Today, the Chinese are worried that many of their industries and jobs will migrate to Vietnam and other lower-wage countries, even though China's per capita GDP is still significantly lower than that of the advanced economies.

Wages in successful emerging economies will eventually approach the levels of the developed world. However, only countries that leveraged know-how and capital acquired during the pursuit of Strategy B to develop superior products that are necessary for Strategy A have succeeded in breaking into the ranks of developed nations. Those that fail to accumulate the necessary know-how and capital might initially achieve a certain amount of export-driven economic growth, but investment slows once domestic wages rise to a level that makes Strategy B unprofitable. Growth in these countries then stagnates as they find themselves in the so-called middle-income trap.

The middle-income trap refers to the slowdown in economic growth that occurs when rising domestic wages cause a country to lose its status as a low-cost producer. When that point is reached, domestic and foreign companies start moving factories to emerging economies with even lower wage costs. That causes investment and growth to decline unless explicit reforms are undertaken to increase the return on capital, thereby prompting both domestic and foreign companies to continue expanding their investment in the country.

Indeed, only a handful of countries outside the West have managed to escape this trap and achieve advanced-economy status. This short list contains Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore, while the number of countries struggling to escape from the trap continues to increase with globalization. As more and more developing countries adopt the export-led growth model and enter the global supply chain, many middle-income countries are facing challenges—in the form of this “trap”—that are similar to those faced by pursued countries.

Demographics and Corporate Investment Decisions

Where do demographics, a favorite subject of economists, fit in this framework? In today's globalized market, domestic demographics should have increasingly less influence on corporate investment decisions—except when a firm has difficulty finding workers or its business is closely tied to the fortunes of a certain geographic region. In all other cases, it should be global demographics that matter for businesses operating in a globalized market.

Amid this diminished influence, an increase in the population will certainly be viewed by businesses as a good reason to expect consumer-led growth if those new additions to the population are able to find jobs and earn income. For those jobs to materialize, however, businesses themselves must feel that demand for their products will increase in the future.

A growing population is certainly one reason for businesses to believe that demand for their products and services will increase. However, few businesses are likely to rely solely on this factor when making investment decisions unless they are a monopoly, or something close to it. Instead, they will probably pay more attention to what their research and development departments are doing relative to competitors at home and abroad. They will also be watching factors that drive short- and medium-term fluctuations in demand, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, demographic trends are one factor in businesses' investment decisions, but usually not the dominant one.

Demographics may, however, have an outsized psychological influence on investment decisions if growth turns negative. If businesses are unable to find enough employees for their factories, that is a legitimate reason to move the plants overseas. But too often, businesses—even those that are globally active—may use a shrinking population as an excuse to do nothing. The author has encountered many global portfolio investors who skipped Japan altogether because “soon there won't be any Japanese left.” This is in spite of the fact that Japan remains the third largest economy in the world, and its companies still dominate many fields requiring cutting-edge technologies.

Even in those countries where the population is growing rapidly, if new entrants to the labor market are unable to find gainful employment—perhaps because of insufficient education or opportunity—the expanding population will only worsen poverty without adding much to economic growth. If poverty undermines social stability, businesses may be even less inclined to invest, and the country's economic growth will stagnate further. Many developing countries today are suffering from this kind of population explosion and the resulting social unrest.

When war-torn Japan faced this problem of too many people chasing too few jobs and social services in the 1950s, the government actively encouraged emigration of its people to destinations in South America so that those who remained had a chance to advance themselves economically. Many governments in the emerging economies of South and Southeast Asia today are also encouraging their workers to go abroad to reduce overcrowding at home. Some of these governments are even counting on those workers' overseas remittances to bolster their foreign currency reserves.

The fact that such de-population policies have had a positive impact on economic growth in certain developing countries suggests there may be an optimal rate of population growth that varies with the stage of economic development. In other words, both excessively high and excessively low population growth (relative to the optimal rate) can be detrimental to economic growth. Ultimately, the economic growth that relies on population growth is neither desirable nor sustainable because the planet simply cannot take unlimited expansion in human population.

Demographics as Endogenous to Economic Development

Demographic trends are also dependent on the stage of economic development. Before the Industrial Revolution, when most people lived on farms, families tended to have more children because the infant mortality rate was high, and children were expected to work on the family farm. There were also religious pressures in many parts of the world not to limit the number of children.

Once the economy enters the urbanizing industrial age, families tend to have fewer children, but rapidly increasing incomes—especially during the post-LTP golden era—and a fall in the infant mortality rate due to better public health often cause the population to expand, sometimes dramatically. Some of the emerging economies currently exporting workers are facing just this sort of population explosion.

Once the economy enters the pursued phase and becomes a post-industrial “knowledge-based society,” the birth rate falls even further. This happens not only because more women join the workforce, but also because parents realize that only children who receive a good education are likely to do well in such a society. This last point is most prominent in the education-obsessed East Asia, where birth rates have dropped sharply as families decided to have fewer children so that the children they do have can receive a quality education.

This trend has been amply demonstrated by the sustained decline in China's birth rate to the second lowest in the world after South Korea even after the government ended its one-child policy. It suggests that demographic trends are to a large degree endogenous to the stage of economic growth.

The Three-Pronged Reforms Needed for a Pursued Economy to Stay Ahead

In the pursued economies, where there are no more low-hanging investment opportunities and populations are aging, policy makers pushing for growth should concentrate their structural reform efforts on at least three areas. First, they should seek supply-side reforms such as deregulation and tax cuts that are designed to increase the return on capital at home. Second, they should encourage labor market flexibility so that businesses can take evasive action to fend off pursuers. Third, they should revamp the educational system to address both the increased human-capital requirements and the greater inequality that are specific to pursued economies.

These three challenges are unique to countries in the pursued phase, and these three policies are necessary for pursued countries to remain advanced economies. Policy makers must also pay more attention to trade deficits to safeguard free trade, as is explained in Chapter 9, and refrain from relying excessively on monetary policy, as is discussed in Chapter 4.

How the United States Answered Japan's Challenge

On all three fronts of structural reform, it is instructive to start with the real-world experiences of the United States in fending off Japan. This is the story of a pursued country that lost its high-tech leadership and then regained it two decades later. When the United States began losing industries left and right to Japanese competition in the mid-1970s, as is described in Chapter 3, it pursued a two-pronged approach in which it tried to keep Japanese imports from coming in too fast while simultaneously shoring up the competitiveness of domestic industries.

The United States utilized every means available to prevent Japanese imports from flooding the market while pushing for market-opening measures in Japan. These included dumping accusations, the Super 301 clause, various “gentlemen's agreements,” currency devaluation via the Plaza Accord of 1985, and an attempt to revamp the Japanese economy via the Structural Impediments Initiative of 1989. The author was directly involved in the U.S.-Japan trade frictions at that time and can say without qualification that the struggle was neither easy nor pleasant (some of the author's experiences are discussed in detail in Chapter 9).

Meanwhile, “Japanese management” was all the rage at U.S. business schools in the 1980s and 1990s. Harvard University professor Ezra Vogel's Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, published in 1979, was widely read by people on both sides of the Pacific. The business schools also recruited many Japanese students so they could discuss Japanese management styles in their classrooms. The challenge from a seemingly unstoppable Japan, coupled with the U.S. defeat in the Vietnam War, sent national confidence to an all-time low, while consumption of sushi went up sharply.

Reaganomics and Learning How to Run Faster

The United States was fortunate, however, that the supply-side reforms of President Ronald Reagan—who cut taxes and deregulated the economy drastically starting in the early 1980s—addressed the first of the three challenges of pursued economies by raising the return on capital at home. These policies encouraged innovators and entrepreneurs to generate new ideas and products, especially in the area of information technology.

Reaganomics itself was a response to the stagflation of the 1970s, which was characterized by frequent strikes, high inflation rates, substandard manufacturing quality, and mediocrity all around. It was a reaction against organized labor, which was still trying to extend gains made during the post-LTP golden era without realizing that the United States had already entered the pursued phase in the 1970s with the arrival of Japanese competition. The fact that the United States was losing so many industries and good jobs to Japan also created a sense of urgency that a break from the past was urgently needed.

People with ideas and drive began to take notice when President Reagan lowered taxes and deregulated the economy. These people then began pushing the technological envelope in many directions, eventually enabling the United States to regain the lead it had lost to the Japanese in many high-tech areas. Few Americans in the 1980s thought the nation would ever win back high-tech leadership from Japanese companies like Sony, Panasonic, and Toshiba, yet today, even the Tokyo offices of Japanese companies are full of products from such U.S. brands as Apple, Dell, and Microsoft.

In retrospect, “Japanese management” looked invincible in the 1980s, in part, because Japan was in a golden era with numerous positive feedback loops, whereas the United States was already in the pursued era. Today, few people extol the virtues of Japanese management because Japanese companies, now in the pursued era, are grappling with the same problems that confronted U.S. companies three decades ago. Some of them have already gone bankrupt or have been taken over by companies from pursuing countries. Indeed, the author came up with the concept of pursued economies after noticing that Japanese companies today face problems similar to those that U.S. companies struggled with three decades ago. This also implies that both management and labor must change as the economy moves from one era to the next.

The Need for Labor Market Flexibility in Pursued Economies

Reagan also addressed the second policy challenge of pursued economies by pushing hard for a more flexible labor market. This was symbolized by his decision to fire the civilian air-traffic controllers who had gone on strike in defiance of federal regulations and replace them with military controllers. This bold action, widely supported by the public, finally broke the back of the labor unions that were still trying to extend gains made during the golden era.

Once the country enters the pursued phase, the whole economy must become more flexible to enable its businesses to take evasive action to fend off pursuers. Foreign competitors may suddenly show up from anywhere, often with a vastly different cost structure. When faced with such competition, businesses must downsize or abandon product lines that are no longer profitable and shift resources to areas that remain profitable.

These tough decisions—which must be made without delay—make it difficult for firms to maintain seniority-based wages and lifetime employment because both effectively turn labor into a fixed cost and undermine management's ability to take evasive action. Attaining this flexibility is a new challenge that is unique to the pursued era.

In contrast, during the golden era, when a country is a global leader or is chasing someone without being chased by anyone else, there is typically no need for evasive action. With a promising road ahead and no one visible in the rear-view mirror, businesses take a forward-looking approach and focus on finding good employees and retaining them for the long term. Seniority-based wages and lifetime employment are therefore typical features of the golden era—especially at successful companies—since such measures help maintain a stable and reliable workforce. In the United States, IBM and other top companies had lifetime employment systems during the golden era.

Reagan's deregulation, tax cuts, and anti-union actions enhanced the ability of U.S. businesses to fend off competitors from behind. Even though those measures hurt labor and aggravated income inequality in some quarters, chances are high that without them the post-1990 U.S. resurgence would have been much weaker or faltered altogether. After trying everything from protectionism and currency devaluation to studying Japanese management techniques, the United States concluded that when a country is being pursued from behind, the only real solution is to run faster—that is, to continuously generate new ideas, products, and designs that encourage consumers and businesses to over-stretch.

Supply-Side Reforms Need Time to Produce Results

Although the U.S. success in regaining the high-tech lead from Japan was a spectacular achievement, it took nearly 15 years. Reagan's concepts were implemented in the early 1980s, but it was not until Bill Clinton became president that those ideas bore fruit. The U.S. economy continued to struggle during Reagan's two terms and the single term of George H.W. Bush, who had served as vice president under Reagan.

The senior Bush achieved a number of monumental diplomatic successes, including the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and victory in the first Gulf War. Yet he lost his reelection campaign to a young governor from Arkansas named Bill Clinton whose only campaign slogan was, “It's the economy, stupid!” Bush's election loss suggests the economy was still far from satisfactory in the eyes of most Americans 12 years after Reaganomics was launched.

Once Clinton took over, however, the U.S. economy began to pick up—even though few today can remember any of his administration's economic policies. Things were going so well that the federal government was running budget surpluses by Clinton's second term. The conclusion to be drawn here is that while supply-side reforms are essential in a pursued economy, it can take many years for such measures to produce macroeconomic results that the public can recognize and appreciate.

The time needed for structural reforms to produce enough domestic investment opportunities for businesses to over-stretch themselves means the government must operate as “over-stretcher of last resort” in the meantime if the economy is in Case 3 or 4. There is simply no substitute for fiscal stimulus in the short run when the private sector is unable to find sufficient domestic investment opportunities to absorb all the savings generated in the economy.

Structural reform is not a panacea, either. Many economists argued for structural reforms instead of fiscal stimulus in post-1990 Japan and in the post-2008 Eurozone. But both economies suddenly lost steam not because of structural problems, but because they were suffering from post-bubble balance sheet problems. And only a government acting as borrower and spender of last resort can help an economy in a balance sheet recession, as is explained in Chapter 2.

The Challenge of Finding and Encouraging Innovators

With regard to the third challenge—having the right kind of educational system to match human capital requirements in pursued economies—the United States was fortunate to have had a long tradition of liberal arts education that encouraged students to think independently and challenge the status quo. Such thinkers are essential to creating the new products and services that are needed by businesses pursuing Strategy A in advanced countries.

The problem is that not everyone in a society can come up with new ideas or products, and it is not always the same group. It also takes an enormous amount of effort and perseverance to bring new products to market. But without innovators and entrepreneurs willing to persevere, the economy will stagnate or worse. The most important human-capital consideration for countries being pursued, therefore, is how to maximize the number of people capable of generating new ideas and businesses and how to incentivize them to focus on their creative efforts.

Only a limited number of people in any society are able to come up with such ideas. They are often found outside the mainstream because those in the mainstream have few incentives to think differently, and only those with an independent perspective can create something new. Some may also show little interest in educational achievement in the ordinary sense of the word. For those who want to create something new, learning about what was discovered in the past often seems a waste of time. Indeed, many successful start-ups have been founded by college dropouts.

Many innovators and potential entrepreneurs may infuriate and alienate the establishment with their “crazy” ideas. If sufficiently discouraged by the orthodoxy, they may withdraw altogether from their creative activities. Finding these people and encouraging them to focus on their creative pursuits is therefore no easy task.

In this regard, the West's tradition of liberal arts education has served it well. In particular, the notion that students must think for themselves and substantiate their thinking with logic and evidence instead of just absorbing and regurgitating what they have been taught is crucial in training people who can think differently and independently.

At some top universities in the United States, students who simply repeat what their professor said may only receive a “B” grade; an “A” requires that they go beyond the lectures and add something of their own. This training encourages them to challenge the status quo, which is the only way to come up with the new ideas and products that are essential for businesses pursuing Strategy A.

Liberal arts education has a long tradition in the West. It started with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, when the value of the human intellect was finally recognized after being suppressed for centuries by the Catholic Church. This long struggle to free the intellect from church authorities was not an easy one, and many brilliant thinkers were burned at the stake. Societies that went through this long and bloody struggle therefore tend to cherish the liberal arts tradition.

Societies that did not experience such struggles, however, may have to guard against the tendency of the educational hierarchy to worship “authorities” to the detriment of independent thinkers. Once such a hierarchy is established, it becomes difficult for new thinkers to gain an audience, especially when their ideas challenge the orthodoxy. The implication here is that citizens' creativity may not be fully utilized in societies where the educational establishment and other authorities continue to act like the Catholic Inquisitors of the past.

One problem, however, is that a true liberal arts education is expensive. It requires first-rate teachers to guide and motivate students, and those persons with such abilities are usually in strong demand elsewhere. Tuition at some of the top U.S. universities has reached almost obscene levels as a result. Furthermore, the ability to think independently does not guarantee that students will immediately find work upon graduation. As such, this type of education is usually reserved for those who can afford it, which exacerbates the already worsening income inequality in pursued economies as is noted in Chapter 3.

The Need for the Right Kind of Education

In contrast, the cookbook approach to education, where students simply absorb what teachers tell them, is cheaper and more practical in the sense that students at least leave school knowing how to cook. The vast majority of the population is exposed only to this type of education, where there is limited room to express creative ideas or challenge established concepts. Creative minds may be buried and forgotten in such establishments, like the proverbial diamonds in the rough.

In pursued economies, teachers in all schools should be asked to keep an eye out for students who seem likely to come up with something new and interesting. Once found, those students should be encouraged to pursue their creative passions.

The United States always had an excellent system of liberal arts education that encouraged students to challenge the status quo. It was therefore able to maintain the lead in scientific breakthroughs and new product development even as it fell behind the Japanese and others in manufacturing those new products at competitive prices.

In contrast, many countries in catch-up mode adopted a cookbook-style approach to education, which can prepare the maximum number of people for industrial employment in the shortest possible time. When a country is in catch-up mode and pursuing Strategy B, this type of system often appears sufficient because the hard work of inventing and developing something new is already being done by someone else in the developed world.

However, these countries will have to come up with new products and services themselves once they exhaust the low-hanging investment opportunities stemming from urbanization and industrialization. The question then is whether they can modify their educational systems to produce the independent and innovative thinkers and entrepreneurs needed for Strategy A in the pursued era. This can be a major challenge if society has discouraged people from thinking outside the box for too long since both teachers and students may be unable to cope with the new task of producing independent thinkers.

Although people in most societies can recall the names of famous native innovators and entrepreneurs, the issue for national policy makers is whether there are enough people like this to pull the entire economy forward. All the advanced countries are now in the pursued era, and they all need more innovators. Policy makers must therefore work harder to create an environment that will allow innovators to flourish. Countries with large populations may also need more innovators.

The Increased Importance of Education in the Pursued Era

Education also has a bigger payoff in the pursued era because a worker's income depends more on individual abilities than in the golden era, when it was often determined by macroeconomic factors such as GDP growth and by institutional factors such as union membership.

Moreover, businesses in the pursued era will not be investing as much in productivity-enhancing equipment to increase worker productivity as they did in the golden era. Even if they did, those investments would not benefit the workers as they had during the golden era. This means workers must take responsibility for educating themselves and expanding their skill sets if they want to improve their living standards.

The fact that workers are on their own in the pursued era also means inequality will worsen compared with the manufacturing-led golden era if workers do not improve their own skills. This makes education one of the few areas in which policy makers can address the pursued era's inherent tendency to exacerbate inequality.

This inequality problem, both real and perceived, has grown to the point where everything has become more difficult, including the reforms needed to overcome the challenges faced by the pursued economies. The difficulty has arisen in part because low or nonexistent wage growth for a large part of the population in pursued economies has made the average person less tolerant and forgiving compared with the golden era, when everyone was enjoying rising wages.

Ensuring equal access to a quality education is one area where policy makers can help reduce inequality in the pursued era. Given the high social and political costs of inequality in the advanced countries today, addressing this issue with improved educational access and quality makes good economic sense.

Unfortunately, this is one area where President Ronald Reagan failed miserably. Although his supply-side and labor-market reforms were essential for a pursued economy, he swung to the other extreme on education by drastically cutting federal spending. As Peter Temin of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology pointed out, this is one of the key reasons why inequality and the social divide in the United States have become such a big problem three decades later.3 If Reagan had understood that improving education is one of the three necessary policy initiatives for pursued economies, the U.S. social divide would be much smaller than it is.

Donald Trump made the same mistake. Although his supply-side reforms and efforts to help domestic manufacturers instead of Wall Street financiers were laudable, he also cut the federal budget for education. This worsened the nation's already serious inequality problems and made it more difficult to implement the policy changes needed to overcome the challenges of a pursued economy.

The Challenge of Keeping Students in School

Education is also far more important in the de-industrializing pursued era than in the manufacturing-led golden era because most good jobs in the former are in “knowledge-based” sectors requiring higher levels of education. In some countries, including the United States, the challenge in terms of education starts with the need to keep students in school long enough to learn something useful. Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen noted in a speech on June 21, 2016, that the median U.S. income is $85,000 for Asian-Americans, $67,000 for whites, and $40,000 for African Americans.4 And this order is consistent with the number of years they spent in school.

From the author's own experience with both the Japanese and American educational systems, this gap is due, at least in part, to the fact that many, if not most, Asian youth are brainwashed to the extent that the option of not studying no longer exists in their minds. The default option is to spend most of their waking hours studying.

When the author attended a Japanese elementary school as a boy, his school happened to have no classes on Saturdays, when nearly all other schools in the country did. When the author left the house on Saturday mornings, he was frequently stopped by adults asking him why he was not in school, as though he were some kind of delinquent. And each time he had to explain that his school had no classes on Saturdays. This shows just how much social pressure there was on every child in Japan to be in school studying five and a half days a week.

When the author moved to the United States at the age of 13 and enrolled in a public junior high school, he was shocked to find that many students there had no intention of studying at all. It came as a surprise because the idea that a 13-year-old could get away with not studying was unthinkable for someone from East Asia. And he envied these students because they seemed to enjoy their teenage lives much more than he did.

Fifty-five years later, some of those who neglected their studies might regret their decisions. But 55 years ago, in the midst of the “Golden Sixties,” many of them probably thought they could make a decent living without studying so hard. At the time, the United States was in its golden era, and it was quite possible for someone without an advanced degree to buy a three-bedroom house and a car with a V-8 engine, automatic transmission, and power steering.

Many of them saw their parents, who also lacked advanced degrees, still doing relatively well and assumed that the good life was within easy reach. Little did they know that the well-paying manufacturing jobs that generated rising wages for their parents would be lost to pursuing economies and that their lack of education would prevent them from moving higher up on the jobs ladder.

In retrospect, it could be said that the good life experienced during the golden era, when everyone benefited from economic growth, created a false sense of security for many who came to believe it would continue forever. Thus they were caught totally off guard when the United States entered the pursued phase.

Had they grown up in a country where they could see what happens to workers when a country enters the pursued phase, they probably would have been more diligent students. But there was no example for them to follow in the United States and Western Europe because they were the first ones in history to experience this phase of economic development. In a sense, those who did not apply themselves to their studies constitute a lost generation, since it is now too late for many of them to go back to school. These frustrated people blame their plight on visible targets such as immigrants and imports. Many of them also supported Donald Trump's “America First” policies. Their inclination to support extreme-right agendas, however, does not change the fact that they themselves lack the skills today's businesses need. Although their frustrations are understandable and some social safety net must be provided, at the end of the day people must realize that they need to acquire skills that are in demand since the clock cannot be turned back.

The High Price of Asian Educational Achievement

Many Asian-Americans, on the other hand, are the offspring of recent immigrants or are first-generation immigrants themselves. For centuries, China (starting in 598 A.D.) had an imperial examination system that assured upward social mobility for the educated. In Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, the focus on education was such that the largest building in most villages, towns, and cities a century ago was often the public school rather than city hall or mansions for the well-to-do.

With so much emphasis on education, the cultural imprinting to study hard still affects many of their offspring in the United States and elsewhere. Because of this cultural straitjacket on the issue of educational achievement, even the dimmest Asian student ends up studying and acquiring some useful skills. They may not be the most creative or articulate within their respective fields, and aspirations and talents that fell outside the confines of formal education may have been suppressed to the detriment of their self-actualization and true happiness, but at least they earn a decent paycheck.

Indeed, an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) survey of “life satisfaction” among 15-year-olds in 2015 indicated that Japan ranked 42 out of 47 countries, followed by South Korea, Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, and Turkey.5 In other words, the youth in these countries are having a miserable time. Meanwhile, the same East Asian countries all placed in the top 10 in the latest OECD scientific literacy tests. These results suggest the cultural differences regarding education that the author experienced 50 years ago still hold today—that is, educational achievement in Asia comes at a high cost. But those who study manage to earn a decent living, which pushes up the average income for the group.

For the other two groups, which do not have such a pervasive cultural straitjacket, much depends on the family or environment in which the child is raised. This is because it takes 15 years or more to realize the payoff from education. At a time when it is said that American corporate executives can only see as far as the next quarterly earnings report, it is a tall order for a child to commit to education when the economic payoff of such effort is 12, 16, or even 20 years away. Most students will therefore need a great deal of outside support to continue their long educational journey.

Those from families and communities with a strong commitment to education will naturally go further than those who do not enjoy such support. Even in households where parents are often absent or too busy to help, being a “nerd” is not so painful if the student is surrounded by hard-working classmates. But studying can be very hard for youths who do not receive support and encouragement to stay in school when others like them seem to be having so much fun outside school.

It is these youth who need help, because their eventual inability to contribute to the economy will be a loss to the entire society. They must also be made aware that they are now effectively competing with youth in the emerging world who are studying and working hard to achieve the living standards of those in the developed world.

An advanced degree is not for everyone, of course, but all students need to know what they are good at and what they enjoy doing so they can make appropriate choices given their personal circumstances. The emphasis on personal strengths and circumstances is important because workers in the pursued phase are really on their own, and the chances are high that they will not do well in a field they do not enjoy.

This means counselors advising students at regular intervals might have just as big an impact on the student's (and society's) final educational outcome as teachers and parents. In addition to supporting students who need outside encouragement to further their education, these counselors can help students discover what they are good at and what they enjoy doing so they can be directed to areas where they are likely to succeed. If possible, these counselors should also be trained to spot independent thinkers and encourage them to pursue their ideas further.

The Importance of a Proper Tax and Regulatory Environment

To maximize people's creative potential, countries in the pursued phase must also revamp their tax and regulatory regimes. It must be emphasized that to create something out of nothing and bring it to market often requires so much effort that “any rational person will give up,” in the words of Steve Jobs. In a similar vein, Thomas Edison famously claimed an invention is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.

Although some people are so driven that they require no external support, most find outside encouragement important during the long, risky, and difficult journey of producing something the world has never seen before. Financial, regulatory, and tax regimes should therefore do everything possible to encourage such individuals and businesses to pursue their pioneering efforts.

Thomas Piketty cited the retreat of progressive tax rates as the cause of widening inequality in the post-1970 developed world.6 But the United States, which led the reduction in tax rates, has regained its high-tech leadership while Europe and Japan, which did not go as far as the United States, have stagnated. This comparison suggests that tax and regulatory changes might have to be drastic enough for people to take notice.

The United States is considered one of the most unequal countries in the developed world, with the top few percent owning a large share of the nation's assets. But those at the very top are mostly founders of new companies (Figure 5.1) who have transformed the way people live and work around the world. Except for Warren Buffett, who made his money investing in the stock market, all of them became rich by taking risks and bringing something completely new and useful to the world.

There are some further down the list who made money in largely zero-sum financial or real estate investments or through established companies and inheritance. But in no other country is the list of the wealthiest people dominated by those who have created transformative technologies. The fact that seven of the top eight in the United States are self-made individuals with transformative ideas suggests that inequality has different implications in the United States than in other countries, where the top ranks are dominated by more traditional and established types of wealth.

Figure 5.1 suggests that the gradualist approach preferred by the traditional societies of Europe and Japan may not work well when a drastic push in innovation is required as the economy enters the pursued era. This outcome also suggests that a tax regime that was reasonable when a country was not being pursued may no longer be appropriate when it is.

| Rank | Name | Industry | Net Wealth |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeff Bezos | founder Amazon | $201 B |

| 2 | Elon Musk | founder Tesla, SpaceX | $190.5 B |

| 3 | Mark Zuckerberg | founder Facebook | $134.5 B |

| 4 | Bill Gates | founder Microsoft | $134 B |

| 5 | Larry Page | co-founder Google | $123 B |

| 6 | Sergey Brin | co-founder Google | $118.5B |

| 7 | Larry Ellison | co-founder Oracle | $117.3 B |

| 8 | Warren Buffett | chair and CEO Berkshire Hathaway | $102 B |

FIGURE 5.1 Richest Persons in the United States

Source: Forbes, “The Forbes 400: The Definitive Ranking of the Wealthiest Americans in 2021,” edited by Kerry A. Dolan, https://www.forbes.com/forbes-400/#45b49a177e2f

The Importance of Interpreting Inequality Statistics Correctly

One should also be careful when interpreting data on inequality, which are often presented as though we still live in an agricultural society. The key asset in an agricultural society is land. When data for such societies say the top 10 percent of the population owns 60 percent of the wealth, it is safe to assume that the other 90 percent is either crowded into slums in the remaining 40 percent of the country or is relegated to the status of sharecroppers with no hope for economic advancement.

Today, however, the wealth possessed by the richest individuals in the United States consists chiefly of shares in the companies they founded. For example, 91 percent of Jeff Bezos' wealth consists of shares in his own companies. The ratio is 97 percent for Mark Zuckerberg and 85 percent for Elon Musk. The shares in those companies are valued by the market and the public, not by an expropriation decree issued by a monarchy or a dictator. In other words, it is wealth that is created instead of being taken or stolen from others.

An increase in the wealth of these individuals therefore does not entail a decrease in the wealth of others, although that is what is often implied by those presenting such data. Moreover, most people in the advanced countries can lead dignified lives even if they are not especially rich.

In those agricultural societies where land ownership is largely in the hands of a privileged few, land reforms that give ownership rights to former sharecroppers often result in vast improvements in productivity and economic well-being. Similar expropriation policies in advanced countries today, on the other hand, might discourage risk-taking and over-stretching to such a degree that the economies would implode.

There are also certain risks that only wealthy individuals can take. Institutional investors and banks must comply with a host of governance rules designed to prevent the public's money from being exposed to excessive risk. But those rules make it difficult for such institutions to invest in start-ups, where failure rates are high but new ideas are often incubated and hatched.

It is said, for example, that only one in eight start-ups succeed. In other words, investors in this space typically experience seven failures before seeing a single success. Fund managers in banks or pension funds cannot post such a high failure rate and hope to keep their jobs. A rich individual who is accountable only to him- or herself, on the other hand, can allocate a certain amount of his wealth to such investments and wait out the seven failures to reach the one winning bet.

The United States also has an ecosystem of highly successful individuals who help nurture start-ups as venture capitalists. That has allowed the nation to stay ahead of other countries in many areas. While this system tends to make the rich even richer, it actually creates wealth instead of taking it away from someone else.

It is therefore time to treat inequality statistics in the advanced countries with a little more caution. They are not equivalent to land ownership data in agricultural societies.

Better Distribution of Medical Care or More New Medicine?

Another frequently raised inequality issue in the United States is the high cost of medical care. This is important because most Americans, who are brought up in the pioneering spirit of self-reliance, really do not want to talk about inequality as long as they are earning a living wage and have a dignified life.

Their rugged sense of self-reliance, however, could be shattered overnight with a catastrophic medical bill. Indeed, a huge share of personal bankruptcies filed in the United States is due to this cause. Even for those who are lucky enough to be healthy and have good health insurance, the fear that they might lose one or both at any time is undermining their faith in the system.

There is a huge room for improvement in the U.S. medical industry, especially in comparison to those available in Japan and some other countries. For example, an appendicitis operation in the United States can easily cost 20,000 dollars when the same operation in Japan can be done for only 3,000 dollars.7 Although Japanese doctors frequently complain that they are not paid enough, this one-to-seven difference in cost is adding to the sense of inequality and insecurity among many people in the United States. In other words, if an average American faced Japanese medical bills, his or her sense of inequality would be far less.

At the same time, it is said that almost all new drugs that are brought to the market in the world today are developed in the United States. This is because the United States does not impose a cap on drug prices the way it is imposed in very many other countries, including Japan. As a result, drug companies can recoup the enormous cost of developing a new drug only in the United States. This is indeed one of the reasons why the medical cost in the United States is so high.