SECTION 7

PROJECT PLANNING AND CONTROL

,

7.2 Establishing Project Priorities

7.4 Project Monitoring, Evaluation, and Control

7.8 Outsourcing Project Management

7.9 Establishing a Project Management System

7.10 Managing Costs in Projects

7.11 Project Work Breakdown Structure

7.1 PROJECT PLANNING

7.1.1 Introduction

Project planning is the process of having a vision for the project and thinking through the strategy for how a project will be implemented to achieve the desired goals. The finished plan will describe what is to be accomplished and how it is to be accomplished as well as stating what will not be done.

Project planning is perhaps the most important part of a project in that it defines goals and strategies by sorting through several courses of action to select the most favorable roadmap. Once the goals that will lead to client satisfaction are defined, all planning leads to their achievement through concentrated effort to describe the roadmap and application of resources to various tasks or work packages.

Project planning is a top-down approach to the continual elaboration of details that explicitly documents the objectives, goals, and strategies necessary to accomplish the project. A successful plan guides the project team to satisfaction of the project’s cost, schedule, and technical performance goals.

7.1.2 The Need for Project Planning

No single element has more impact on the success of a project than project planning. There are numerous examples of poor planning in projects that caused major replanning efforts during critical times during project execution. Goals have been poorly defined, deliverable products have been redefined, customers have not understood the process, and the project team has been unsure of the next steps. Weak project planning will nearly always yield poor results.

Successful planning leads to successful projects. |

There are many reasons for weak project planning. Some of the more common are:

• Senior management and the customer emphasize starting the work quickly to see some progress in building the product.

• Concepts and principles of project planning have not been taught in U.S. schools of higher education.

• Project team members have little experience or training in project planning.

• Project planning and project execution are different skill sets.

7.1.3 Organizational Context for Project Planning

Project planning is done within the context of the organization—relying heavily on the organization’s strategic and business goals. All planning must flow down from the organization’s high-order plans to ensure that project planning is accomplished within the context of the organization’s:

• Mission or purpose

• Strategic and business objectives and goals

• Project management capabilities

Projects must have a strategic and operational fit with the organization to be successful. When projects are randomly started or selected without regard for the business, industry, or technology, it is highly likely that they will not meet their full potential for the organization.

7.1.4 Project Plan Contents

A project plan for a large project requires extensive description of project management components and the functions that are required. A project plan would include the following items.

• Scope statement—the description of the project, its goals, and the extent of the project in terms of technical, time, and cost.

• Work breakdown structure (WBS)—the division of the project into manageable parts for work assignment and control. The WBS also will be used in such areas as communication, cost estimating, scheduling, and work authorization.

• Schedule—the work laid out over time, which will typically be at two levels, detail and summary. The schedule will also contain milestones for the control of project progress and validation of work accomplishment.

• Project budget—the cost estimate converted into a time-phased expenditure plan that gives an expected rate at which funds will be used to complete the project.

• Risk assessment—the detailed analysis of the project’s work and associated risk. The assessment will give visibility into areas of risk for managing throughout the project.

• Interface plan—the description of external interfaces for the project’s product. This may be physical, electrical, hydraulic, digital, or other external connections for the project’s product.

• Work authorization plan—the process and practice for authorizing the release and completion of work packages. It is a part of the control mechanism for regulating and validating work accomplishment.

• Logistic support plan—a document that describes the means for supporting the project’s product after the project is complete. It may describe such items as the repair and maintenance of the product once it is commissioned.

• Communication plan—the description of the process and practice of communicating project information to internal and external participants. This would typically include a list of who is to receive what information and the frequency. Team meeting management would also be described in this document.

• Procurement plan—the description of the goods and services that will be obtained for the project, to include details on when to request them and when they are needed for the project.

• Quality assurance plan—the description of actions to be taken to build confidence that the project’s product will meet client needs.

• Human resource list or plan—the list or description of human resources required for the project and when they are needed. Typically, an organization will name individuals, but often there will only be a skill identified for a period of time.

• Stakeholder management plan—the description of the stakeholders and how they will be managed in a proactive manner to ensure the project progresses as planned.

• Project closeout plan—the process and practices to be used to close all activities and reassign resources upon completion of the project. This may include transition planning for handover of functions or activities that must be continued, such as transfer of a building that was used by the project team.

• Product commissioning plan—the process and practices to be used to commission a product, such as testing an electrical generator for the client and operating the generator for a period of time.

Project plans consist of several sections or chapters, depending upon the size of the project and the extent of project planning. Planners may scale down the following list of sections to fit the project size and need for detailed instructions. All projects regardless of size will have the following—some formally stated in a project plan and others informally stated.

• Project statement of work (SOW)—a succinct description of the work to be accomplished and how it will be accomplished. The SOW may include blueprints, drawings, and other illustrations that describe the work.

• Technical specification—the technical parameters for a product that will result from the project. Typically, this document describes the details of a product to be built. It should be noted that a part of the project may be to write the technical specifications for client approval.

• Technical goals for the project—a list of the features, attributes, and functions that the project must achieve to be successful. These may be included in the SOW and technical specification.

• Schedule goals for the project—a list of dates and accomplishments that must be achieved. This may include dates for project phases, milestones for critical dates to be met, and project review dates. Project planners will typically focus on the end date or the product delivery date.

• Cost goals for the project—a single or phased list of expenses for the project. Short projects typically have a single dollar value stated, whereas long-term projects may have time-phased expenditure requirements.

7.1.5 Sequence of Planning Actions

Planning is a building block process—sequence is important. |

Project planning should follow a sequence that builds on prior planning and document development. The detailing of tasks and actions is a logical flowdown from higher-order documents. This hierarchy of documents requires that one be completed before another is started. Thus, the sequence of planning is important.

• Project charter—this is typically the first project document and follows project selection. It describes in general terms the project’s purpose, general parameters such as time and cost objectives, appointment of the project manager, definition of the roles and responsibilities for all participants on the project team, identification of the client, and any other authorization or limitation placed on the project manager.

• Requirements definition—the process of converting general statements into measurable parameters for the project’s product and service. Technical parameters and descriptions must be documented to establish the description of the end product—the objective of the project.

• Project planning sequence—the sequence of building the project plan, like a schedule, aligns the order in which planning will be accomplished. First in planning is to define what is the end product of the project and describe it fully to promote understanding about the product’s scope. This is typically the technical specification and statement of work. Next, one can schedule the work, followed by the pricing of work. Once these functions are accomplished, other planning will use pieces and parts to develop plan components.

7.1.6 Project Work Packages

Critical to project success is the process of defining project work packages. Project work packages are the lowest level of management for project work. Whereas the detailed WBS defines the lowest-level part of the projects, the natural work package may be a combination of these parts. These are combined into work packages for assignment and tracking of progress to one work unit—whether it is a single person, a small team, or a vendor.

Uses and consideration for use of work packages are many. Some of the more important items are as follows:

• Decide which work packages will be done in-house.

• Identify project work packages that will be subcontracted.

• Obtain the commitment of the responsible functional work managers.

• Plan for the allocation of appropriate funds through the organizational work authorization system.

• Develop procurement specifications and other desired contractual terms for the delivery of the goods and services to be provided by outside vendors.

• Develop the master work package schedule.

• Identify the strategic issues that the project is likely to face.

• Estimate the project costs.

• Develop the project budgets, funding plans, and other resource plans.

7.1.7 Competences for Project Planning

Planners must know what can be translated from a plan to a working situation. Simple concepts and straightforward work approaches in plans are more easily put into practice than complex approaches. Planners should not make the project plan any more complex than needed to describe the requirements.

Planners need to visualize the overall requirement and describe in detail how tasks are to be performed. Planning is accomplished from general to specific. Planners must identify the general requirement and continue to elaborate on the work until it is in sufficient detail for another person to understand.

Planners also must understand the fundamental principles of planning. Planning is taking a mission, developing goals, assembling facts, supplementing facts with assumptions, and describing the process. Treating an area lightly or omitting facts or assumptions can lead to a flawed plan.

7.1.8 Planning Responsibilities

The primary responsibility for planning the project typically rests with the project leader. The project leader prepares the project plan, using the project team and other available resources, for presentation to senior management. The plan must be complete and describe the entire process for performing the project work and delivering the product to the customer.

Project team members are responsible for contributing to the development of the project plan and ensuring that the work described can be achieved with the listed resources. Team members contribute their technical knowledge of the product and the process by which it is built. Working cooperatively, team members ensure the project plan is factual and realistic for the performing team.

Senior management is responsible for approving a complete project plan that is success-oriented. Senior management also has responsibility for rejecting a weak plan or one that does not meet the criteria for describing the project’s work. Weak plans result from poor planning and inadequate review by the approval authority.

Functional managers are also responsible for project planning when they have elements to prepare. For example, an engineering function may prepare the drawings that graphically describe the product. Any weakness in the drawings will transfer to the plan and ultimately the project.

7.1.9 Adverse Affects on Project Planning

There are many different items that can have both positive and negative impacts on project planning. These items need to be considered from the applicability and potential negative impact. Remember that the success or failure of the project may hinge upon one or more items.

A list of items that can adversely affect project planning and the quality of the resulting project plan follows. This list is not inclusive, but it provides a general identification of areas for consideration.

• Need for clear customer requirements and understanding with the customer

• Need for well-defined goals for quality/technical, schedule/time, and cost/price

• Need to identify facts and assumptions regarding the project

• Need to identify issues related to the project and resolution prior to project execution

• Need for a capable tracking and control system to be in place prior to project execution

• Need for a risk analysis to be conducted prior to project execution and mitigation or completion of contingency planning

• Need to identify the right skills and resources during planning and ensure that they are available through normal procedures (either internal to the organization or contracted)

• Need to identify interfaces and dependencies and coordinate same

• Need to identify major issues during project planning

• Need to ensure work is planned to be accomplished by phase and that there is an approval process to move to each new phase

• Need to see closeout of the project is planned and delivery or transition of the product is defined

These top-level items are essential to ensure the detailed planning is conducted. Detailed planning for the project follows the organization’s project methodology and defines the individual requirements. This detailed plan provides the guidance to team members on how to execute the project.

7.1.10 Common Errors and Excuses of Project Planning

There is a tendency to make excuses for poor planning. This is a natural reaction when the person feels that planning has little value to the project. Some examples used in different projects reflect the types of excuses.

• Actual situation was poorly defined requirement. “I use rolling-wave planning. I plan a little and work a little.” This excuse is an attempt to say the planning for the project can be done in phases or “waves” without the requirement being well thought through. Incomplete planning during the planning phase will not converge on the technical solution. Any plan that does not include all phases and the delivery of the product is flawed. Delivery of the product in the plan demonstrates an understanding of the technical solution.

• Improper use of assumptions. “I have an assumption that covers that part of the project.” This is an attempt to divert attention away from a critical aspect of the project and avoid doing the required research or coordination of that area. To continue with an assumption when the matter should be resolved is to have a flawed plan.

• Lack of documented facts. “I don’t list facts because they never change.” Facts must be listed because they form the basis for the project and are supplemented by assumptions where facts are not available. Listing facts also ensures that the plan approving authority has all information regarding the project and agrees to those facts.

• Mixing facts and assumptions. “I don’t differentiate between facts and assumptions. They are all the same to me.” Facts and assumptions are uniquely different in that facts change only when there has been a misunderstanding. Assumptions are anticipated future positive outcomes that must become true statements or the project will be impacted. Assumptions require tracking and managing to ensure a successful project.

• Inadequate planning. “Plans never come true anyway. So I just wing it and please the boss with something that looks good.” Actual performance seldom exactly replicates the project plan, but in many cases is very close to the plan. Planning provides a direction and ensures most areas are thought through and options are weighed. Good plans will ensure most situations are covered and then the few variations can be managed.

• Complex plans. “My plans are so sophisticated that most people cannot understand them. Planning is one of my strengths.” Any plan that is complex or unduly complicated will probably be misunderstood or misinterpreted. Plans should be simple and complete. Planning is to make things clear and avoid confusion.

• Planning projects from technology orientation. “It takes someone familiar with the technology to do the planning.” Understanding the technology may be required in some areas of preparing a project plan. However, most of the planning is around the business aspects of the project, and the planner needs to understand how the organization works, how schedules will work, where resources are located, how much the project will cost, and how to communicate with all stakeholders.

There are many examples of errors and excuses used in planning. These are typically used when the planner is unsure of what is required in the plan or an area seems to be intuitively easy. When the plan-approving authority acts on an incomplete plan, he/she becomes a part of the weakness in planning.

7.1.11 Benefits of Proper Project Planning

Significant benefits are derived from thoroughly planning projects. Benefits have not been documented because of inadequate measures of effectiveness for comparison between projects. Industry, project size, and technology involved dictate the parameters that should be used to plan a project. Some rules of thumb that have been gleaned over several years of planning and implementing projects give some guidance.

Good project planning yields benefits. |

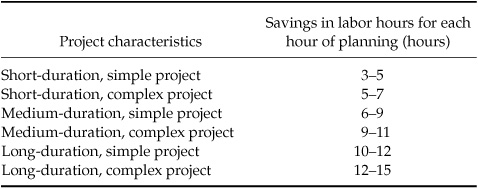

The range of these rules of thumb is dependent on the planning knowledge and skills of the project team as well as the willingness of senior managers to enforce proper planning. It is obvious that planning, as the foundation for future project work, should be in the range of 3 to 7 percent of the time and budget. More complex projects may require more time and funds. Table 7.1 is an example of a rule of thumb for planning.

Benefits of proper planning show that good plans lead to projects that can be more easily executed in a consistent fashion for better end results. Plans that guide project execution to the proper technical solution are of significant benefit to an organization in terms of productivity and profitability.

TABLE 7.1 Rule of thumb for project planning benefits

Experience shows that significant savings in time can be achieved by proper planning. Some rules of thumb have been developed based on more than 20 years of work on projects. The duration and complexity of the project play significantly in the savings. There is an increased savings when proper planning is performed on more complex and longer-duration projects.

In high-technology industries, the rule of thumb is a ten-to-one ratio for execution savings to planning for small to medium-sized projects with moderate complexity. For each hour spent planning, it is expected that ten hours will be saved in execution. This approximation assumes minimum planning skills by the project team. However, the planning process must be proven and adequate to result in a complete project plan.

7.1.12 Summary

Project planning is hard work that requires the commitment of several levels within an organization to ensure completeness and validity. The planners must do their best to write instructions for project execution at the proper level of detail. The project leader must provide guidance and develop the project plan that is a continual elaboration on the customer’s requirements. Most important, senior management must approve for implementation only plans that provide the project the best possibility of success.

Several items mitigate against good project planning. Both the customer and senior management often place emphasis on starting the project work (execution) before the planning is complete. This view of project work assumes more progress when the team is doing the project’s work. The importance of planning is played down.

Proper project planning has a beneficial effect on the success of the projects and reduces the stress on the executing project team. Proper project planning gives the customer and senior management the best prediction of the outcome of the project. Proper project planning also compresses the execution time for the project and reduces waste through rework.

7.2 ESTABLISHING PROJECT PRIORITIES

7.2.1 Introduction

In today’s dynamic work environment, it is often a question of setting priorities for our work and doing those first tasks that have the most urgency of need. If Parkinson’s law is correct that work expands to fill the time available, we need to identify and meet our obligations to the important work. Too often, we find ourselves inundated with tasks and without a plan or priority for the work.

Getting important work done first is critical to business. |

One individual stated the obvious when met with conflicting tasks: “I’m so busy with so many tasks that all I have time for is to make excuses why I am not getting anything done.” This is a situation where he should stop worrying about tasks until there is some order of importance assigned—either self-assigned priority, or let the boss sort the tasks as to urgency of need.

Another individual stated, “My boss keeps giving me more work and I don’t have time to complete the tasks that he has given me before.” When advised to make a priority list that ranked the urgency of need for the work efforts, he stated that the boss would just say, “Get all of the tasks done.” This individual was unable to either get his boss to prioritize the tasks or to put them into an urgency-of-need ranking. He did not have the time or people to perform all the tasks.

Projects are no different than individual work efforts—everything needs some ranking as to what is important and urgent. Projects established without a priority, or ranking as to what is needed first, create situations that are disruptive and conflicting for the person charged with leading the effort. Too often, everything is considered “priority one” by senior management.

7.2.2 Importance of Project Work

Most people will agree that projects are important because they were selected by the organization as a worthwhile venture. The degree of importance may be debated based on how one sees the contribution of a project to the organization. Some examples of the importance of projects are listed below.

• CEO—project makes a large revenue contribution to the organization.

• Vice president of projects—project is a showcase of what a project should be and an example for future project work.

• Director of finance—project requires a low investment of funds to perform and has a good cash flow into the organization.

• Project manager—project is doable with the available resources and gives a lot of satisfaction to the project team.

• Director of engineering—project has a challenging product design that will stretch the ability of our engineers.

• Director of marketing—project will meet the expectations of our clients and result in a lot of sales.

As seen from these examples, different people in the organization can assign unique definitions of importance to projects. These definitions of which project is most important rely on one’s organizational position rather than the organization’s goals. It is essential that the importance of work be defined through the goals, both strategic and operational, for the organization to ensure growth. Importance for a project, viewed from the organization’s goals, could be a combination of all the factors listed above.

The most important projects should receive first consideration for resources. |

“Urgency” relates to time and how soon the project’s product is needed. Priorities for projects show the relative order of need and the emphasis that must be assigned for allocating resources to perform the work. A “priority one” would receive resources before a “priority two” project, and so on, if there were conflicting resource requirements. A priority system guides managers in allocating resources as well as tracking the schedule for delivery.

“Urgency of need” is important for managing projects to meet the goals of the organization. When a priority system is flawed or not present, decision makers are often without the guidance to consistently emphasize and support projects that should be first in line for resources. Uninformed decisions can materially affect the organization’s business and impact client satisfaction through late deliveries.

7.2.3 The Project Priority System

Often the size of a project is identified as the priority for a product or service. Large projects are assumed to have the highest priority, and the resultant priority for resources. This type of priority system is flawed in that many times a small project has a significant impact on the organization’s business and is needed immediately. Resources should be given first to that project that must be delivered first.

Project priority is based on the contribution to the organization’s goals. |

The urgency of need for a project, or its priority, should be based on the project’s contribution to the business. Personal criteria should be set aside when establishing a priority for a project because those criteria may conflict with supporting the organization’s goals. A rigorous system of assigning priorities to projects is needed to ensure congruence with the organization’s purpose.

7.2.4 Rationale for Prioritizing Projects

Organizations should develop a list of reasons for assigning a high priority to a project. These reasons would flow down from the strategic and business goals as well as be supportive of marketing efforts. Some reasons for assigning a high priority to a project are listed for consideration.

• Promised project deliverables to client on a specific date.

• Early delivery of products to increase revenue stream.

• Project’s product feeds another important project.

• Project’s product improves company image.

• Project has a high potential for follow-on work if accomplished early.

Senior managers must decide which projects are more important—or the project manager and team members will. |

When there is no priority ranking, all projects take on equal status and importance. Senior managers with the responsibility for assigning a priority, or order of importance, to a project pass the decision to lower levels. Project managers working without a priority will typically assume that their project is the most important for the organization and seek resources on that basis.

Project team members working in a matrix organization often have latitude as to which project they will work on to accomplish specific tasks. When the priority is either “all is priority one” or there is no priority, the team member must make the decision as to what is to be accomplished. Experience shows that team members will sort on the following items to select the work when given no distinction between projects.

• Work that is most interesting or challenging

• Work supporting the project manager they like

• Work that is easiest to accomplish to show progress

• Work where friends are working

7.2.5 A Model Project Priority System

A model is a guide to a better solution. |

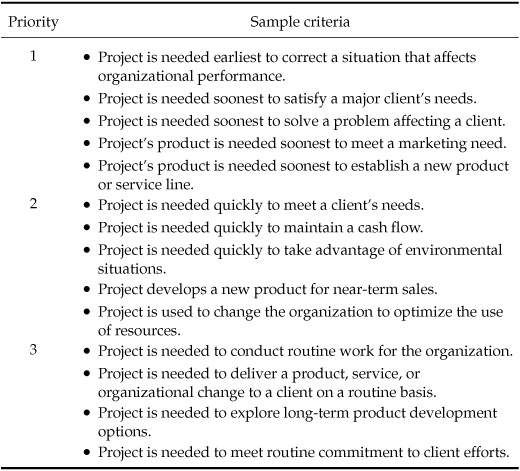

A typical project priority system should have from three to five priority categories. More categories diffuse the system, while fewer than three may not have the individual characteristics with which to differentiate between projects. The following may be a start for an organization in establishing a project priority system (Table 7.2).

TABLE 7.2 Sample Project Priority System

The above generic priority system is just a start at ranking the importance of projects to the organization. One needs to first identify the strategic and operational goals to ensure alignment of priorities with the organization’s purpose. Too often, “pet projects” serve the interests of a person rather than the organization. Linkage to the goals in a priority system is therefore critical to organizational success.

The drawbacks to selecting and implementing projects that do not have a priority based on organizational goals are many. Some of the more common issues are as follows:

• Project is unique and receives resources that should be used elsewhere.

• Project may contribute to an individual’s agenda without benefit for the organization.

• Project is not a building block for organizational success.

• Project detracts from the “real work” of the organization.

7.2.6 Implementation of a Priority System

Once a priority system is defined and established in policy, there is a need for rigorous implementation to ensure the benefits are realized as soon as possible. The above three-level priority system is an example of what might be implemented, but with greater detail for how priorities are assigned and how they may be changed on a project.

Organizations without a priority system need to establish a working group to review all active and candidate projects for their contribution to the organization. Using a guide and understanding the strategic, business, and marketing goals of the organization, the working group would classify all projects into groups. An example of the classification groups might be as follows:

• Continue the project and change its priority to a higher ranking.

• Continue the project and change its priority to a lower ranking.

• Continue the project and retain its priority.

• Terminate the project as being inconsistent with the strategic and operational goals of the organization. Harvest all product components or scrape all components.

• Modify the project to align with the organization’s strategic and operational goals. Assign a priority consistent with the project’s contribution to the organization.

• Place project on hold until a review is conducted to determine its value to the organization.

Project priority can change during the execution phase to either a higher priority or lower priority. If the organization’s goals change, there is a need to ensure the project is still a viable entity within the changing direction. Changes to the strategic goals, for example, could cause a project to be cancelled if the organization was no longer pursuing a particular product line. Another situation that could cause a change to priority is a shift in the market or a client’s needs.

7.2.7 Advantages of a Priority System

A project priority system, when properly used, makes the decision process a rigorous process based on facts and organizational needs. Random ranking of project priorities results in less than optimal performance for the organization through poor resource allocation and utilization. Some rationale for establishing and using a disciplined process is suggested:

• Better utilization of resources by placing the resources where they will do the most for the organization

• Reduced conflict between projects for resources by establishing the order of importance for projects

• Possible termination of projects that are low yield and low priority

• Possible expedited projects to gain early benefits for important projects

Priority systems establish the basis for selecting projects and communicating the importance of each project to the organization. When consistently applied, a priority unifies the efforts of everyone in the organization toward success—i.e., the best allocation of resources to meet the organization’s goals. Without a system of priorities, allocation of resources becomes a random process.

7.2.8 Summary

Priorities for projects establish the basis for allocating resources to meet the organization’s strategic and business goals. When senior managers insist that all projects are “priority one,” the decision as to what is important is passed to the lower echelons of workers to decide what to do first. These individuals, typically, do not have the information or knowledge of the organization’s operations to make a valid selection of “important work.”

Randomly selected and prioritized projects typically do not apply the proper emphasis on delivering products through projects in an efficient manner that is supportive of organizational goals. Random selection of projects increases the risks against achieving organizational goals through an arbitrary process that may or may not be consistent with the project management process.

Developing and implementing a prioritization system for projects that are unique to the organization should be tailored around the strategic and business goals. Any change to these goals should trigger a review and adjustment to the priority allocation system. Further, there should be a review of the system if the environment or client’s needs change.

7.3 PROJECT SCHEDULING

7.3.1 Introduction

Scheduling of projects is considered one of the basic requirements of project planning. Over the past 60 years, scheduling has matured and the tools associated with scheduling have improved significantly. Scheduling tools are available to nearly all projects for developing time lines.

Through the use of automated tools, almost any project team member can accomplish scheduling. These schedules vary in sophistication and utility based on the understanding that the preparer has of scheduling practices. There is a tendency to either put too much in a schedule or too little. The right balance is often not known by the preparer.

Another challenge to proper scheduling is the definition of terms used by different tool manufacturers for product differentiation. Some refer to the schedule as the project plan and others mix the terms for the lowest level of work in the schedule as task, activity, or work package. Standardization of the terms is needed to ensure consistent communication of the schedule components.

7.3.2 Key Scheduling Definitions

The key definitions used in scheduling include:

• Task—the lowest level of work in a project schedule.

• Milestone—the non-resource-consuming task that is used to signify a critical control point in the schedule. Milestones use neither time nor resources.

• Critical path method (CPM)—a method of network scheduling that determines the longest time path through the project. The longest path is called the critical path and there may be more than one critical path. CPM, in its original form, depicted the tasks by the arrows and the nodes showed logical connectivity.

• Program evaluation and review technique (PERT)—a method similar to CPM that uses three time estimates to calculate the longest time path. PERT and CPM are used interchangeably by some individuals.

• Precedence diagram method (PDM)—a CPM derivative scheduling method that uses the nodes for tasks and the arrows for logical connectivity.

• Work breakdown structure—a disciplined process of defining the product within a project. It decomposes the project’s work to the required visible level and defines those items. (See Sec. 7.11.)

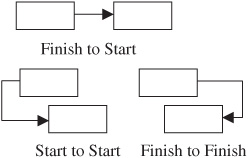

• Scheduling relationships for tasks—the logical relationship between two tasks. There are three recommended relationships: (1) “finish to start” when one task is completed and the next one starts; (2) “start to start” when two tasks start at the same time; and (3) “finish to finish” when two tasks are completed at the same time. These relationships are often modified by lead (prior to) or lag (following) time constraints.

7.3.3 Project Schedule Purposes

The basic purpose of the schedule is to describe the work that will be accomplished over time. This laying out of the work on a time line provides the plan for the work sequence and at what time to start and finish tasks. Sequencing the work ensures that it is all in the time frame for the project and that the project completion is identified.

A second purpose of the schedule is to communicate to all stakeholders that all work has been included for the project and that tasks will be accomplished at a specified time. The communication of this information ensures confidence is conveyed for the project’s activities. This coordination of the scheduled work supports a united effort in completing the project.

The third purpose of the schedule is to establish the benchmark for comparing the actual performance with the plan. The schedule depicts what is expected and actual performance shows how closely the work results match. Schedule validity is achieved when there are no significant, unexplained variances.

7.3.4 Preparing a Schedule

Preparing a schedule requires using the WBS, which defines the project work. This work is then converted to tasks and summary tasks that depict work to be accomplished. The WBS defines the product or functions required for the complete project and should be used to provide discipline to the process.

Some organizations use a task list to develop the schedule items. This method has application in research projects and projects without the formal structure required of a disciplined process such as the WBS. In these projects, the outcome or product of the project is unknown. Using a task list also gives a random level of detail for tasks as well as opens the possibility that some tasks are not identified.

Once the tasks are identified, place them in a Gantt chart or bar chart format. Scheduling tools permit this and allow manipulation of the information to continue the process. Use a standard task duration as an initial solution and connect the work into its logical sequence for performance.

Evaluate each task to determine whether it is a “fixed duration,” requires a fixed amount of time regardless of the number of resources, or if it is “effort driven,” may expand or contract based on the assignment of resources for completion. Assign resources to the tasks and develop a critical path.

Figure 7.1 shows a simple Gantt chart that has tasks with different durations and relationships. This chart also includes lines showing the relationship between tasks. The chart does not show whether the tasks are fixed duration or effort drive, have a fixed start or the links drive the start, and if the tasks are resource loaded or not.

Milestones are inserted in the schedule at critical points to signify completion of a phase or transition to another work group. In the above example, the one milestone used is for completion of the project. Other milestones may be used to control components of the work and for reporting purposes.

Simple relationships between tasks are best to schedule the work when one task is complete and the next one is started (finish to start). There are occasions that dictate task relationships such as two tasks beginning at the same time (start to start) and two tasks completing at the same time (finish to finish). These may entail delays or advances on one or the other task to make the relationship more complex.

FIGURE 7.1 Simple Gantt chart.

FIGURE 7.2 Task relationship chart.

As a rule of thumb, the finish to start for tasks should be used for about 90 to 95 percent of the relationships. Start to start should be approximately 3 to 7 percent of the relationships. Finish to finish should be 2 to 3 percent of the relationships.

Figure 7.2 shows the relationships of tasks. The upper left tasks show the finish to start relationship. Below and to the left is the start to start relationship with the finish to finish relationship just to the right.

A fixed duration task is shown in the upper area of the next illustration. This task cannot be reduced in duration regardless of the number of resources assigned. An example of this is a four-hour meeting with 10 people. If eight attend or if 12 attend, the meeting is still four hours in duration.

An effort-driven task is shown in the lower area of the illustration. The shaded areas in Fig. 7.3 depict change in duration. The longer shaded area indicates that less than one full resource is assigned to the task; say for example, one person is assigned 50 percent of the time. Less than a full resource causes the task to become longer in duration. The shaded area above the task indicates more than one resource is assigned and the task is therefore shorter in duration. For example, assigning two people to a task reduces the duration to half the estimated duration.

7.3.5 Resource Loading a Schedule

Assigning resources to a schedule is accomplished by matching the proper skill sets with the task requirements. Resources are only assigned to the lowest level tasks and no assignments to milestones. At least one resource is required for each task, while some large tasks may require several resources with similar or different skills.

The number of resources assigned determines effort driven task duration. Each additional resource decreases the duration of the task. There are, however, limitations on the number of resources that can effectively work on a single task. Large tasks may need to be divided for better control and resource utilization. Some principles for assigning resources to tasks include:

• Assign one resource per task as a minimum and make that resource full time on the task.

• Assign similar resources to tasks for the same amount of time to ensure best effort.

• Ensure resources are assigned by name rather than skill to identify specifically who will be working on tasks.

• Update the schedule with the resources at least 30 days in the future (some resources will leave the organization and not be available for the project).

7.3.6 Schedule Tracking and Control

The resource-loaded schedule is implemented after being approved by the project leader or senior management. Implementation is the allocation of tasks to be started and ensuring the resources are informed when the work is to start. This initial effort starts the clock running on the project toward the completion date.

Project status and progress are collected on a periodic basis, typically weekly. The performing individuals report tasks completed, percent complete of tasks, and percent remaining on started tasks. Actual progress is posted to the schedule and variances are plotted. Variances represent work that is ahead or behind schedule.

Variances in the schedule may result from inadequate estimates of the amount of work required on tasks, poor control over the work being accomplished on the tasks, lower productivity levels on the tasks, or late starts on tasks. Variances must be analyzed to determine the impact on the schedule and costs. Major variances may require significant changes to the schedule while minor variances may only dictate the situation be more closely monitored.

Variances on the critical path have the potential for negatively impacting the project completion date. These variances may require additional resources be placed on tasks on the critical path or that the logical relationships between tasks on the critical path be changed. Any change to the schedule will probably be less efficient than the original schedule unless there is better information for predicting the future.

7.3.7 Summary

Scheduling is a mature technique and practice. Tools and techniques have been perfected that support the rapid development of schedules and ease of change. These tools and techniques, however, use subjective data, such as estimates of task duration and estimates of labor skills that can materially affect the outcome of the project’s delivery on time. Scheduling skills are familiar to many members of the project team and each may assist in developing or managing the time line.

Schedules should be as simple as possible for ease of development and ease of understanding by all the stakeholders. Relying on the fundamental procedures and practices of scheduling will provide a solution that is superior to complex task relationships and resource assignment by less than 100 percent of effort. The more complex is the schedule, the more difficult is the management of the schedule.

Tracking and controlling the schedule status and progress provide the measurement of the effectiveness of the schedule as a plan for the project. Significant variances and discovered work are indications of weak schedule planning. Small variances and explainable variances give assurance that the schedule is workable and represents the best solution for the project.

7.4 PROJECT MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND CONTROL

7.4.1 Introduction

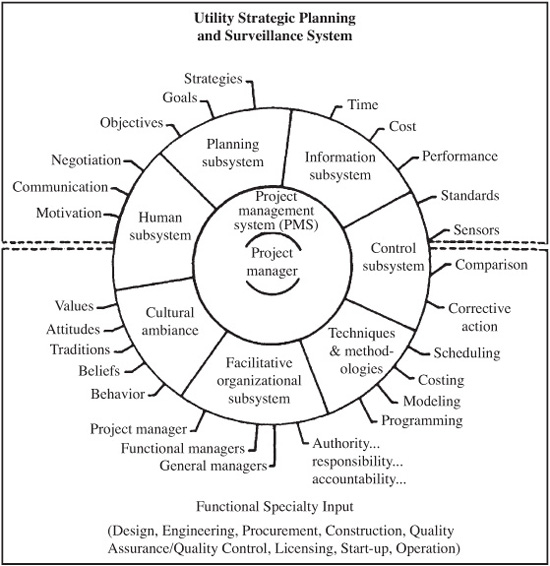

In this section, information will be provided concerning how project performance can be monitored, evaluated, and controlled. Control is the process of maintaining oversight over the use of the resources on the project to determine how well the actual project results are being accomplished to meet planned project cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives. There are four key elements in a control system as depicted in Fig. 7.4.

FIGURE 7.4 The project control system. (Source: David I. Cleland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, 3d ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 1999, p. 325.)

In order to properly assess project progress, several conditions and understandings are required. These are:

• Team members must understand and be committed to the importance of the process of project monitoring, evaluation, and control.

• Information derived from the WBS is required to measure project progress.

• The work package is the basic project unit around which progress on the project can be measured and evaluated.

• Information used for project control purposes must be relevant, timely, and amenable to the plotting of trends in the use of project resources.

• Measurement of project results must start with an evaluation of the status of all of the work packages on the project.

• Information collected and compiled concerning the status of the project must be tempered by the judgment of the project team members and executives concerned.

7.4.2 Elements in the Control System

These elements are drawn from Fig. 7.4.

1. Establishing standards from the project plan typically include:

• Scope of work

• Product specifications

• Work breakdown structure

• Work packages

• Cost estimates

• Master and supporting schedules

• Technical performance objectives

• Financial forecasts and funding plans

• Quality/reliability standards

• Owner satisfaction

• Stakeholder satisfaction

• General/senior manager satisfaction

• Project team satisfaction

• Vendor/subcontractor performance metrics

• Project team effectiveness

• Other performance standards derived from the project plan

2. Observing performance involves receiving relevant, sufficient and timely information about the status of the project, which comes from many sources:

• Formal reports

• Briefings

• Informal conversations

• Review meetings

• Miscellaneous documentation, such as customer perceptions; letters; e-mail; memoranda; audit reports; “walking the project”; observations; talking with stakeholders; listening; and listening some more

During the project review meetings, asking and seeking answers to the following questions can give valuable insight into how well the project is doing. These questions include:

• Where is the project with respect to schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives and goals?

• Where are the project work packages with respect to schedule, cost, and technical performance objectives and goals?

• What is going right on the project?

• What is going wrong?

• What opportunities are emerging?

• Does the project continue to have an operational or strategic fit with the organization’s mission?

• Is there anything that should be done that is not being done, and are we doing things we shouldn’t be doing?

• Are the project stakeholders comfortable with the results of the project?

• How is the project customer’s image; is the customer happy with the way things are going?

• Has an independent project evaluation been conducted?

• Is the project being managed on a total “project management systems” basis?

• Is the project team an effective organization?

• Does the project take advantage of the strength that the organization possesses?

• Does the project avoid a dependence on the weakness of the organization?

• Is the project making money for the organization?

Ongoing monitoring of the project performance should be carried out at the following levels:

• The work package level

• The functional manager’s level

• The project team level

• The general manager’s level

• The project owner’s level

3. Comparing planned and actual performance in the use of resources on the project to determine how well such use has contributed to the fulfillment of the project objectives. Project performance must be evaluated on a regular basis to identify variances from plans.

An important part of the control process is to take preventive action to solve actual or anticipated problems. The major preventive actions include strategies for:

• Overall change control that involves coordinating project changes across the entire project

• Scope control

• Schedule control

• Cost control

• Technical (product) control

• Risk control

The functioning of an effective project control system in the context of comparing planned actual performance includes the opportunity to find answers to several questions about the project:

• How is the project performing?

• If there are deviations from the project plan, what are the causes of these deviations?

• What can be done to correct these deviations?

• What can be done to prevent these deviations in the future?

• How many open issues are there compared with our history of projects at this point and size?

4. Corrective action can take many strategies to bring the planned and actual use of resources back into harmony. Some of these strategies include:

• Replanning

• Reallocation of funds

• Reallocation of resources

• Reassignment of authority/responsibility

• Rescheduling

• Revising cost estimates

• Modification of technical performance objectives

• Change project scope

• Change product specifications

• Terminate the project

• Stopping work on the project and replanning/redirecting the entire project

7.4.3 Project Audits

Project audits provide an opportunity to have an independent and expert appraisal of where the project stands. The basic purposes of an audit include:

• Determining what is going right, and why

• Determining what is going wrong, and why

• Identifying forces and factors that have prevented or may prevent achievement of cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives

• Evaluating the efficiency of existing project management strategy, including organizational support, policies, procedures, practices, techniques, guidelines, action plans, funding patterns, and human and nonhuman resource utilization

• Providing for an exchange of ideas, information, problems, solutions, and strategies with the project team members

TABLE 7.3 Project Audit Activities

A project audit should cover key activities depending on the nature of the project. A sample of these key activities is included in Table 7.3.

7.4.4 Postproject Reviews

Postproject reviews can serve to identify and pass on to other project teams the efficiency and effectiveness with which a particular project has been managed. Such reviews provide insight into the degree of “success” or “failure” of a project, as well as a composite of lessons learned from a review of all the projects in the organization’s portfolio of projects. The results of such reviews can provide insight into such matters as:

• Accuracy of estimating project costs

• Better means of anticipating and minimizing risk

• Evaluation of project contractors

• Improve future project management

7.4.5 Summary

In this section, the basic control cycle was presented as a model on which to base a philosophy and process for the monitoring, evaluation, and control of a project. The key elements in this control cycle were explained, along with suggestions on what could be done by way of corrective action to get the project back in harmony with the project plan. Finally, basic ideas were presented about project audits and postproject reviews as a means of evaluating a particular project, and passing on the “lessons learned” to other project teams.

7.5 PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT

7.5.1 Introduction

Risk in a project is the probability that some adverse event will negatively impact the project’s goals. Project goals are the baseline for measuring the risk to the project and the risks are typically against the cost, time, and technical goals. There may be other goals, such as customer satisfaction, that will be considered.

All projects have some risk or there would not be projects. Projects are initiated when there is some element of risk and management wants the sharp focus of a project plan and team to perform the work. Too much risk is sometimes assumed without the requisite understanding of the elements that can cause the project to fail. Too little risk means the project is not pushing the thresholds for cost, time, and technical performance.

7.5.2 Project Uncertainty

Uncertainty is a major contributor to project risk. Complete uncertainty is the total lack of information while certainty is the totality of information. Projects will typically not have all the information to plan and execute the work. Sometime a project leader may have as little as 40 percent of the required information and must proceed because of commitments to customer or market conditions. It is estimated that project leaders will have between 40 and 80 percent of the required information during the planning phase of most projects.

Figure 7.5 shows the complete range of available information and gives a perspective of the spectrum of complete uncertainty to complete certainty.

Uncertainty is often accounted for in project assumptions. When there is insufficient information available to make a decision or plan a project, assumptions bridge the gap. Assumptions are reasonable, but not without the probability of failure if they do not come true.

FIGURE 7.5 Uncertainty to certainty spectrum.

Project uncertainty has been identified in several different areas within an organization. Some of the areas that have been most visible are as follows:

• State of the art for the technology used

• Organizational capability to perform repeatable project management processes

• Availability of technical and project management skills

• Equipment availability for the project

• External project interfaces

• External project suppliers

• Technical impasses

• Test results for products of the project

7.5.3 Internal and External Project Risk

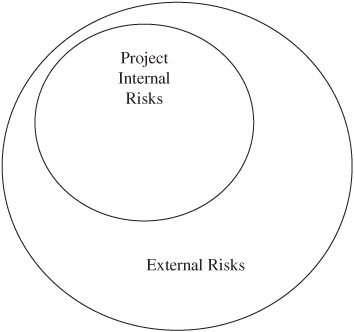

Risk may be divided into two categories: internal project risk and external project risk. See Fig. 7.6 for a conceptual view of the two categories of risk. Internal project risk is that risk inherent in the project that the project leader has control over and can reduce through direct actions, such as developing contingency plans. External project risk is that risk which is outside the control of the project leaders. Examples of this would be project interfaces that are unknown and the interface definitions are being accomplished by another party.

FIGURE 7.6 Project internal and external risks.

Internal project risks are part of the constraints placed on the project through establishing goals. The delivery date for the product may be optimistic and the plan has to reflect that date. Planning will focus on the delivery date and schedule of work to ensure the delivery is feasible. Cost is typically an area that is constrained. Planning will drive the type and quantity of resources that will be used on the project, even when the budget is less than desired. Technical solutions will be placed in jeopardy when the delivery time is optimistic and the funds are limited.

External project risks may be influenced by the project leader and anticipated, but there is no direct control over the risk events. These risks are influenced through agreements and contracts with other parties. The degree of influence exercised by the project leader is determined by the identification of external risks and the cooperation extended by the other party. Some examples of other parties could be other project leaders, functional managers, vendors, and contractors.

7.5.4 Risk Identification

Risk events are the potential adverse affects on the project. Identification of these events should be first made during project initiation and then in project planning. During project initiation, the project leader should be identifying the project interfaces and the degree of difficulty in achieving those interfaces. There may also be early identification of internal project risks through such activities as anticipating using new technology or a new workforce.

Identifying internal project risks during planning starts with the goals and asking whether the plan will deliver the desired results. Starting with the technical aspects of the project, ask the question as to whether the solution is feasible within existing technology. Record any events that may fail and the probability of failure. Some guides to identifying risk are shown Table 7.4.

TABLE 7.4 Risk Identification Practices

• Checklists for project risk areas |

• Lessons learned from previous projects |

• Resource availability lists |

• Resource training records for applicable skills |

• Peer review of project plans |

• Senior management reviews of plans |

• Organizational project management capability audit |

Identify the schedule failures as planning is being accomplished. The schedule must have the assigned and available resources to perform the work or there is risk associated with the lack of qualified personnel to perform the work. The delivery of the product is always subject to evaluation for feasibility of finishing the work. Milestones may be dictated that would also be subject to evaluation for feasibility.

Cost risk is the total of the materials to build the technical solution and the human resources to perform the work. Other costs may be in the project, such as travel, shipping, and duties that may or may not be major cost drivers. The total cost is a budget that represents the time-phased expenditures for the project. Risks may be from total cost or the rate of expenditure if there is a cash flow constraint.

7.5.5 Risk Quantification

Risk quantification is a means of weighting the risk events so that risks may be ranked for mitigation. Figure 7.7 shows probability on a scale of 0 to 1.0 and the consequence of a risk event. Consequence for cost is in dollars and for schedule is duration of extra time required. Technical risk is the failure to achieve satisfactory functionality or performance. Technical risk is typically translated into additional cost or schedule duration.

A less precise quantification of a risk event is accomplished on a two-dimension matrix that has probability of occurrence on the vertical scale and consequence if the event occurs. The simple matrix of Fig. 7.8 may use a color scheme for management purposes.

Managing risk is accomplished in order of the magnitude of impact on the project. Green, for example, would require only that the risk event be monitored to ensure it did not increase. Yellow would indicate there was a need to actively monitor and reduce the risk where possible. Any increase would trigger a response. Red would indicate that some action is needed to either lower the risk event or take a different approach.

FIGURE 7.7 Risk quantification matrix.

FIGURE 7.8 Risk ranking by intersection.

7.5.6 Risk Mitigation

Mitigating or reducing risk is accomplished through changing the plan, adding resources, using a different technical approach, or other actions. As indicated in the quantification of risk matrix, all red events would be mitigated to either a yellow or green status prior to continuing. This reduction of risk, either through the probability of the event happening or the consequences of the outcome, improves the risk picture for the project.

Risk mitigation may not be possible for a risk event and senior management may be asked to decide whether a high-risk item is acceptable or whether the project should be cancelled. High-risk items may dictate some other action or a delay until better solutions can be found. The decision on risk events that have major consequences is typically reserved for senior management.

7.5.7 Contingency Planning

Contingency planning is a part of risk reduction through identifying and documenting alternative solutions if a risk event happens. When the decision is made to continue in spite of a major consequence, contingency plans are prepared. The contingency plan may be an alternate technical solution for technical problems, contracting out part of the work to a more qualified organization, reducing the scope of work, or using different technology.

Contingency plans for cost or schedule failures could include reducing the technical scope for less work, eliminating part of the project, changing the human resources, or other cost-cutting and work reduction efforts. It is important that the technical scope of the project be determined and whether there are changes to that area first. Cost and schedule changes will typically occur when there is a change to the technical scope.

7.5.8 Contingency Reserves

With several risk events, there will be some occurrences that have both cost and schedule implications. Any technical risk event that occurs will add cost to the project and increase the duration. Therefore, it is best to have some contingency reserves for both cost and schedule. Contingency reserve represents a percentage of the cost and a percentage of the schedule.

A cost contingency can be computed to some degree of accuracy by multiplying the probability of occurrence (probability in the range of 0 to 1.0) by the consequence of the risk event (in dollars). Thus, a risk event that has a probability of 0.6 of occurring and a consequence of $10,000 would have a negative value of $6000. This would be assigned a time for probable occurrence and plotted against the schedule.

A schedule contingency can be computed similarly to the cost contingency. Multiply the probability of occurrence (0 to 1.0) by the additional time that would be consumed (consequence) if the risk event occurred. This provides the negative value for additional units of time that will be required. A contingency of schedule in a high-risk project is a necessity.

Contingency reserves for cost and schedule are not required throughout the duration of the project. Once a risk event has been avoided and the project is continuing, any contingency reserve may be reduced by the amount of the negative value. For example, a cost risk that is avoided would permit release of any funds in a contingency reserve for that event to reduce the amount of money held for future use.

7.5.9 Risk Control Responsibility

The project leader is responsible for managing the project’s risks. Each risk event should be put on a schedule of when it may occur. In this manner, the project leader can monitor risks until they either occur or until the period of time has past. Risks that do not occur can be removed from the active tracking and any contingency can be removed from the project.

By placing the risk in the project schedule, one can maintain the time relationship between risk events. New or emerging risks can be inserted into the schedule, while past events can be marked complete. One method is to use a milestone for each risk event and identify each with a specific risk.

Risks that do not occur are easy to manage. Risks that occur will require intensive effort to maintain the forward progress of the project. Anticipating the risk event and the corrective action that may be required if it occurs will minimize the disruption.

7.5.10 Summary

Risk management requires a rigorous process to identify, quantify, mitigate, and manage risk events. High-risk items should be mitigated first and reduced to the level deemed acceptable by senior management. Moderate and low-risk events may be accepted without mitigation if their negative impact has little effect on the overall project.

In mitigating risk, the first area to address is the technical functions. Any risk in a technical area will typically extend into cost and schedule areas. Once the technical risk events are addressed, then schedule and cost may be addressed.

Schedule risk events will most likely affect cost. Any schedule slippage will affect the cost of resources and any fixed costs for the project. Assessing schedule risk events is the second area to be addressed after technical functions.

Cost is the last area to address and is affected by both technical and schedule. Cost is always affected by technical function rework and schedule delays. The resources required for the rework or new work as a result of risk events occurring will drive cost increases.

7.6 PROJECT AUDITING

7.6.1 Introduction

Project audits are conducted to determine whether the project is performing according to plan. There is an implied purpose of the project being successful, but success is contingent upon the project plan and its ability to guide the project team to a successful conclusion. Audits are a comparison of what is being accomplished versus what was planned to be accomplished.

The project audit is not a random assessment of the project. It is a planned activity that may be scheduled at a time in the execution of the project or when a certain threshold triggers a need for an audit. Planned audits may be conducted at different stages of the execution phase of a project. Triggered audits may be conducted when, for example, a project milestone is not achieved.

An audit validates whether a project is or is not proceeding according to plan. |

7.6.2 Types of Project Audits

Project audits will vary according to the need for comparing the plan to the actual execution practices. Planning and conduct of the audit focus upon the purpose and expected outcome. Typical project audits are as follows:

• Progress audit—the review of project progress in terms of the three primary goals for schedule progress, budget expenditures, and technical progress. The outcome for this type of audit would be a comparison of the planned progress in each of the three areas against the actual accomplishments. This would provide senior management a report on the effectiveness of the project’s execution.

• Process audit—the review of practices by the project team to ensure they are following the prescribed process and that the process is effective in meeting the planned goals. One example of a process audit could be a test of a new piece of equipment to determine the functionality. The test process would provide assurance that the testing was producing the correct results. The results of the audit would provide confidence as to whether the process is capable of producing the desired outcome.

• System audit—the review of a technical or administrative system to ensure it is functioning according to the documented guidance. The system would typically be a project support operation or function such as issue management, change management, or communication plan. These areas would often be supporting functions for the overall project and areas that are critical to ensuring project accomplishment. The result of the audit would be a report on the adequacy of the system to support the project’s work.

• Product audit—the review of the technical accomplishment of the project in building the product. It is a comparison of the technical achievement according to the plan (e.g., product description, statement of work, specification) and compared to the actual. The outcome of the audit gives confidence as to the convergence of the technical parameters and the work. The result of the audit is a report stating the degree of convergence on the technical solution.

• Contract audit—the review of work on the project and a comparison with the contractual requirements to determine compliance. This audit provides confidence that the project team is performing the work required by the contract and that all specific requirements, such as workmanship or process usage, are being met. The result of the audit is a report of the degree of compliance with the contractual requirements.

• General audit—the review of all aspects of a project and a comparison of those planned versus actual accomplishments. This type of audit encompasses all areas of the project and is used to identify noncompliance with the plans, practices, processes, procedures, and requirements. The audit may vary as to the depth of examination and time spent in any one area. The result of this type of audit is a report on the degree of compliance with all requirements for conducting projects.

• Special audit—the review of specific parameters of a project to determine the progress or status of a project. This type of audit is typically triggered by a loss of confidence in the project’s achievements in a specific area and senior management desires to determine the actual progress or status of that area. The result of a special audit is a specifically focused report on the progress or status and, perhaps, recommendations for improvement of conditions.

7.6.3 Audit Teams

Audit teams are formed to conduct the various audits and to report the results of audits. The composition of the team is often dependent on the type of audit and any special purpose. The success of the audit team is dependent on the skills, knowledge, and ability of the individuals and the needs of the project. It is not necessary for a person auditing a project to be technically qualified in project work.

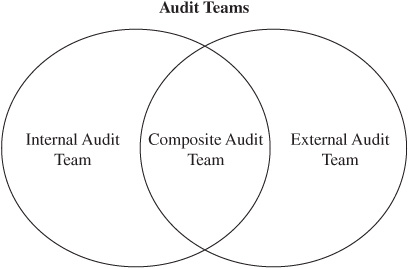

Figure 7.9 depicts the three types of audit teams and the overlap between internal and external team composition.

There are three basic types of audit teams: the internal team, the external team, and the composite team of both internal and external team members. The functions for each type may be similar, but the degree of independence in the audit is the primary difference.

• Internal project audit team—a select group of individuals from a project team that comprises an audit team. This team conducts self-audits of the project functions and identifies compliance issues. The team has credibility with the total project team and team members are familiar with the work. There is a rapid start-up and completion of the audit. Using project team members, however, detracts from the work that was to be performed and does not provide an objective assessment of the audited area.

• External audit team—a select group of individuals with specific skills, knowledge, and abilities that comprise an audit team, but have no member from the project team. This audit team has a high degree of independence and perceived objectivity in making the assessment. It does, however, require time and effort to form, become familiar with the project, and collect information. A dedicated external audit team can minimally impact the project’s progress while reaching objective findings.

• Composite audit team—a select group of individuals with specific skills, knowledge, and abilities that comprise an audit team, and are a mix of both internal and external resources. This composite arrangement obtains critical resources from the project and from other sources to build an audit team that can balance objectivity of assessment with the knowledge of the project work. A composite team has the strengths of being knowledgeable in the project work and the audit function while having minimal impact on the objectivity of the outcome.

There are many variations of the audit team and the source of people to form the team. Constraints on availability of technically qualified people and the urgency of need for the audit may drive a unique solution. One must recognize the strengths and weaknesses of the different variations and how the variations may negatively impact the desired results for the audit.

7.6.4 Planning Project Audits

Project audits must be planned to ensure the pertinent areas are examined and a comparison made of each area with the project plan, project standard, process, procedure, or practice. Planning provides the guide to how the audit will be conducted and what will be examined. Corrective actions are typically not part of the audit, but recommendations made by the project audit team are used to initiate required remedial actions.

A project audit plan should consider the following items:

• Purpose of audit. This is the reason for the audit and what it is to accomplish. An example of a purpose statement could be: “To audit the cost and schedule functions of Omega Project to determine the extent of compliance with the project plan.”

• Scope of audit. This would entail the amount of time to be spent on the audit as well as the areas to be examined. An example of a scope statement could be: “The audit team will have five days to audit Omega Project in the areas of cost and schedule at Newtown Plant. The team will review documents, discuss information with the project team, and compare the information against the baseline. A report will be rendered to Ms. Jo Smith within five working days following the audit.”

• Resources and assignments. This is a detailed list of the audit team and their skills. It would also give general assignments to each person for the audit, to include writing the report of findings.

• Methodology. This is a general approach as to how the audit will be conducted. It may describe the pertinent procedures for the conduct of the audit. For example, it may have detailed instructions as to documents to be reviewed or it may describe the function to be reviewed. This would include any preparation required prior to the audit, such as a meeting to discuss assignments and the depth of auditing services.

• Report. This describes the report that the audit team will render upon completion of the audit. It may range from a simple narrative report to detailed reports with briefings to selected audiences. The report is the deliverable product of the project audit team and represents its efforts in conducting the audit.

Random or quick fire audits do not have the same effectiveness as the planned one. Project audits must be conducted in a formal manner that is understood by the project team as well as senior management. Random and quick fire audits convey a message that the audit team is focused on finding fault. All audits should be to identify those areas in need of improvement and confirm that other areas are performing well.

7.6.5 Conducting the Project Audit

The project audit team, whether an independent or internal team, must always conduct itself in accordance with a set of guidelines that allow them to set a professional atmosphere. The audit team has an obligation to the project team as well as senior management to perform all duties in a professional manner.

Some guidelines that are helpful in conducting the audit are listed below:

• Be prepared to perform your part of the audit and use as little time of the project team as possible.

• Brief the project team on your mission and the time frame that is required to conduct the audit.

• Always ensure the project team members know your role and the mission of the audit team.

• Collect and record information in a formal manner; avoid misleading a project team member to obtain information.

• Allow project team members to initiate corrective action, but never direct any action.

• Do not promise any project team member anything; refer questions about the audit to the audit team leader.

• Be accurate in recording information and confirm the accuracy by obtaining feedback from the project team members.

• Immediately report any unsafe or illegal activity to the project audit team leader.

• When appropriate, give an informal debriefing to the project team prior to completing the audit.