SECTION 2

PROJECT ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN

,

2.1 Organizing for Project Management

2.2 Project Organization Charting

2.3 Authority-Responsibility-Accountability

2.4 Project Management Training

2.1 ORGANIZING FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT

2.1.1 Introduction

This section provides an examination of the organizational design used for the management of projects. It addresses shortcomings in the traditional organization designs as well as the strengths of the project organization.

2.1.2 Shortcomings of the Traditional Organizational Design

• Traditional organizational hierarchies tend to be slow, inflexible, and fail to provide for an organizational focus of project activities.

• Barriers commonly exist in the traditional organization, which stifles the horizontal flow of activities required when projects are undertaken.

• Inadequate delegation of authority and responsibility to support project activities is a common problem in the traditional organizations.

A modification of traditional organizational design is required to support project activities.

The project organization is an integration of the project stakeholders. |

2.1.3 The Project Organization

• The project organization is a temporary design used to denote an interorganizational team pulled together for the management of the project.

• Personnel in the project organization are drawn from the supporting functional elements of the enterprise.

When a project team is assembled and superimposed on the existing traditional structure, a matrix organization is formed. Figure 2.1 portrays a basic project management matrix organizational design.

FIGURE 2.1 A basic management matrix.

2.1.4 Alternative Forms of the Project Organization

Functional organization. The project is divided and assigned to functional entities with project coordination being carried out informally by functional and higher level managers.

The functional matrix. The project manager is assigned with the authority to manage the project across the functions of the enterprise.

The balanced matrix. A design where the project manager shares the authority and responsibility for the project with the functional managers.

The traditional matrix. The project manager and the functional manager share explicit complementary authority and responsibility for the management of the project.

2.1.5 Traditional Departmentalization

The most commonly used traditional means used to decentralize authority, responsibility, and accountability include the following:

• Functional departmentalization, where the decentralized organizational units are based on common specialties, such as finance, engineering, and manufacturing

• Product departmentalization, in which organizational units are responsible for a product or product lines

• Customer departmentalization, where the decentralized units are designated around customer groups, such as the Department of Defense

• Territorial departmentalization, where the organizational units are based on geographic lines; for example, Southwestern Pennsylvania marketing area

• Process departmentalization, where the human and other resources are based on a flow of work such as an oil refinery

2.1.6 The Matrix Organization

In the matrix organization, there is a sharing of authority, responsibility, and accountability among the project team and the supporting functional units of the organization. The matrix organizational unit also takes into consideration outside stakeholder organizations that have vested interests in the project. The matrix organization is characterized by specific delineation of individual and collective roles in the management of the project.

TABLE 2.1 The Project-Functional Interface

2.1.7 The Project-Functional Interface in the Matrix Organization

It is at this interface that the relative and complementary authority-responsibility-accountability roles of the project manager and the functional manager come into focus. Table 2.1 suggests a boilerplate model that can be used as a guide to understand the interface of relative authority, responsibility, and accountability within the matrix organization.

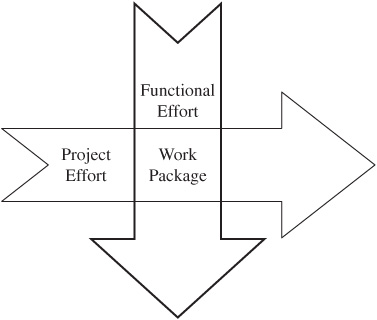

2.1.8 Basic Form of the Matrix

In its most basic form, a matrix organization looks like the model in Fig. 2.2, where the project and functional interface comes about through the project work package. Each work package is a “bundle of skills” for which an individual or individuals have responsibility to carry out in supporting the project.

FIGURE 2.2 Interfaces of the project and functional effort around the project work package. (Source: David I. Cleland and Lewis R. Ireland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2007, p. 193.)

2.1.9 Roles of the Project Manager

Many roles are carried out by the project manager. A few of these key roles are indicated below:

• A strategist in developing a sense of direction for the use of project resources

• A negotiator in obtaining resources to support the project

• An organizer to pull together a team to act as a focal point for the management of the project

• A leader to recruit and provide oversight over the planning and execution of resources to support the project

• A mentor in providing counseling and consultation to members of the project team

• A motivator in creating an environment for the project team that brings out the best performance of the team

• A controller who maintains oversight over the efficacy with which resources are being used to support project objectives

• Finally, a diplomat who builds and maintains alliances with the project stakeholders to gain their support of the project purposes

2.1.10 A Controversial Design

The matrix organizational design has been praised and condemned; it has had its value, problems, and abuses. The review that follows examines some of the characteristics of a weak and a strong matrix.

1. Weak matrix:

• Failure to understand the individual and collective roles of the participants in the matrix

• An inherent suspicion of an organizational design that departs from the traditional model of the organization

• A failure on the part of senior management to stipulate in writing the relative roles to be carried out in the matrix organization

• Lack of trust, integrity, loyalty, and commitment on the part of the members

• Failure to develop the project team

• Individual and collective roles have been defined in terms of authority-responsibility-accountability.

• The project manager delegates authority as required to strengthen the team members.

• Team members respect the prerogatives of the functional managers, and the roles of other stakeholders on the project.

• Conflict over territorial issues is promptly resolved.

• Continuous team development is carried out to define and strengthen the roles of the team members and other stakeholders.

2.1.11 Project Manager–Customer Interface

The interactions between a project manager and the customer are depicted in Fig. 2.3. The reciprocal interrelationships portrayed in this figure are only representative of the myriad of interaction that occurs. Key decisions and factors likely to have impact on the project should be channeled through the respective project managers.

2.1.12 Summary

In this section, alternative designs for the project organization were presented. In such organizations a clear definition of the individual and collective roles of the project participants is required. Several models of organizational design were presented to include the commonly used “matrix organization.” The characteristics of both a weak and a strong design were presented, along with a brief description of the interface that project managers have with customers.

FIGURE 2.3 Contractor–project manager relationships. (Source: Adapted from David I. Cleland, “Project Management—An Innovation in Management Thought and Theory,” Air University Review, January-February 1965, p. 19.)

2.2 PROJECT ORGANIZATION CHARTING

2.2.1 Introduction

This section of the Handbook describes project organization charting, or the alignment of the organization within the context of authority and responsibility. The linear responsibility chart (LRC) is a primary tool for this.

2.2.2 The Traditional Organization Chart

At best, the typical pyramidal organization chart is an oversimplification of the organization because of its general nature. Although it describes the framework of the organization, and can be used to acquaint people with the nature of the organizational structure—how the work in the organization is generally broken down—it lacks specificity regarding individual and collective roles. It does little to clarify the myriad reciprocal relationships among members of the project stakeholders. As a static model of the enterprise, the traditional chart does little to clarify how people are supposed to operate together in doing the work of the enterprise. An alternative is needed—the LRC.

The LRC portrays who works with whom. |

2.2.3 Linear Responsibility Chart

An LRC displays the coupling of the project work packages with people in the organization. These couplings are the outcome of bringing the key elements of an LRC together. These key elements include:

• An organizational position

• An element of work—the work package

• An organizational interface point

• A legend to describe a relationship

• A procedure for creating the LRC

• A commitment to make the LRC work

Figure 2.4 shows the basic nature of an LRC with the “P” indicating primary responsibility for the work package.

FIGURE 2.4 Essential structure of a linear responsibility chart. (Source: David I. Cleland and Lewis R. Ireland, Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2007, p. 234.)

2.2.4 Work Package—Organizational Position Interfaces

A work package is a single, discrete unit of work that has a singular identity that can be assigned to one individual, and to other individuals who are involved in doing the work on the work package. Work packages are directly related to specific organizational positions. These positions and the responsibilities assigned to them in carrying out the use of resources on the work package requirements constitute the basis for the LRC. The authority and responsibility regarding a work package and an organizational position are depicted in a suitable legend, a sample of which follows:

1. Actual responsibility

2. General supervision

3. Must be consulted

4. May be consulted

5. Must be notified

6. Approval authority

Figure 2.5 shows an LRC for the authority-responsibility-accountability relationships within a matrix organization.

FIGURE 2.5 A linear responsibility chart of project management relationships.

2.2.5 Development of the LRC

The development of an LRC should be done cooperatively with the project team members. Once completed, an LRC can become a “living document” to be used for the following:

• Portray formal, expected authority-responsibility-accountability roles.

• Acquaint all stakeholders with the specifics of how the work packages are divided up on the project.

• Contribute to the commitment and motivation of team members since they can see what is expected of them.

• Provide a standard for the role that the project manager and the team members can monitor regarding what people are doing on the project.

2.2.6 Summary

In this section, the use of an LRC has been described as a means of better understanding of the individual and collective roles on the project team. An LRC can serve to facilitate the coordinated performance of the team—since everyone would better understand their individual and collective role on the project team.

2.3 AUTHORITY-RESPONSIBILITY-ACCOUNTABILITY

2.3.1 Introduction

In this section, a description is offered concerning the matter of how authority, responsibility, and accountability (A-R-A) are provided to complement the organizational design used for management of projects.

2.3.2 Defined Authority

Authority is defined as a legal or rightful power to command or act. As applied to the manager, authority is the power to command others to act or not to act. There are two basic kinds of authority:

• De jure authority is the legal or rightful power to command or act in the management of a project. This authority is usually expressed in the form of a policy, position description, appointment letter, or other form of documentation. De jure authority attaches to an organizational position.

• De facto authority is that influence brought to the management of a project by reason of a person’s knowledge, skill, interpersonal abilities, competence, expertise, and so forth.

Power is the possession of an organizational role augmented with sufficient knowledge, expertise, interpersonal skills, dedication, networks, alliances, and so forth, that gives an individual extraordinary influence over other people.

Authority, responsibility, and accountability are unifying forces in organizations. |

2.3.3 A-R-A Failures

Most failures of A-R-A in the project organizational design can be attributed to one or more of the following factors:

• Failure to define the legal A-R-A of the major participants in the project organizational design, such as the matrix form

• Unwillingness of project people to share A-R-A in the project affairs

• Lack of understanding of the theoretical construction of the matrix

• Existence of a cultural ambience that reinforces the “command and control” mentality of the traditional organizational design

2.3.4 Documenting A-R-A

Suitable documentation should be published concerning the A-R of the major project participants. Figure 2.6 is one example of the nature of such documentation.

2.3.5 Defining Responsibility

Responsibility, a corollary of authority, is a state, quality, or fact of being answerable for the use of resources on a project and the realization of the project objectives.

FIGURE 2.6 Project-functional organizational interface. (Source: David I. Cleland and William R. King, Systems Analysis and Project Management, 3d ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 1983, p. 353.)

FIGURE 2.7 Project management organizational design.

2.3.6 Defining Accountability

Accountability is the state of assuming liability for something of value, whether through a contract or because of one’s position of responsibility.

Figure 2.7 is a summary of Fig. 2.6 and is one way of portraying these forces. Cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters are elements around which A-R-A force flow. Each organizational level in this figure provides an ambience for both individual and collective roles.

2.3.7 Summary

In this section, the concepts of A-R-A have been presented. Authority was described as having two major elements: de jure and de facto. Responsibility was described as the state of being held answerable for the use of resources and results. Accountability is the state of being liable for the use of resources in the creation of value. Great care should be taken to develop and disseminate organizational documentation throughout the enterprise that describes and delegates the elements of authority, responsibility, and accountability needed for people to perform on the project.

2.4 PROJECT MANAGEMENT TRAINING

2.4.1 Introduction

Training is an important aspect of raising knowledge levels and changing behavior of individuals on projects. Training gives the individuals greater capability to perform at higher levels of productivity and make greater contributions to project success. Interpersonal skills training is as important as knowledge training on project management functions because of the team challenges in managing projects.

Skill training also is important for the tools of project management. These tools fulfill the requirements for time planning (schedule tool), reporting (graphics and correspondence), cost tracking and computing (spreadsheet), and managing data (database tool). Tool training, however, does not replace the knowledge requirements for project management functions.

All personnel do not require the same type or level of training within knowledge or skill areas. Some training is for familiarization, or broad general knowledge, while other training is for detailed working knowledge. The position and responsibilities of the person dictate the level of knowledge required and training requirements.

Training also has to consider whether the individuals being trained possess knowledge that is inappropriate and must be unlearned prior to new knowledge being learned or whether the training is the first exposure. There is also training to reinforce concepts and knowledge as well as advanced training that builds on prior training.

We trained in the appropriate knowledge and interpersonal skills! |

2.4.2 Project Management Knowledge and Skills

Senior leaders have been promoted within an organization because they are experts in traditional management concepts. Few senior leaders have been involved in project management as a discipline. Those few who have been in project management have not been able to keep pace with the maturing of the methodologies and technologies.

Senior leaders have also been omitted from the training in current project management discipline through failure to develop appropriate courses of instruction. Senior leaders do not need the same level of knowledge and do not need to know the details.

General knowledge of concepts and principles as well as an ability to interpret the information generated by project reporting is more appropriate. Senior leaders must be able to use that information to determine how to support projects, how to link strategic goals to projects, and how to take corrective action when the information gives early signs of failure.

Project leaders must know the overall status of the project at any time. There is a need to be able to interpret the information generated by the project to recognize early signs of slippage in any area. Therefore, the knowledge required is a working level understanding of the project and being able to visualize the convergence of the technical solution. Project leaders must be human resource managers as well as negotiators, communicators, and technically qualified in their industry or discipline.

Project leaders, depending upon the size of the project and the authority delegated, may have the need for more detailed working knowledge to be a “working project leader” or more general knowledge if a “managing” project leader.

Project planners are the principal planners for projects and must have the detailed knowledge of the concepts, principles, techniques, and tools of planning. Planning knowledge and skills are not taught in the U.S. system of higher education. Therefore, many of the planners have learned planning in the apprenticeship method with much of the work being trial and error. Planning, as the design of how the work will be performed, is a critical aspect of project management.

Project team members must be familiar with the methodology and flow of project management before being assigned to a project for the most effective and productive effort. Understanding the guidelines and checkpoints in a project supports the work. They also must understand their role in measuring project progress, such as how to report progress against a schedule.

2.4.3 General Categories of People Involved in Projects

There are generally four levels of individuals who need to have some knowledge of project management. This includes the capability of project management to deliver against strategic goals, approval process, and allocation of resources to projects while tracking their progress, direction of project planning, execution and closeout, and details of the project work and work processes.

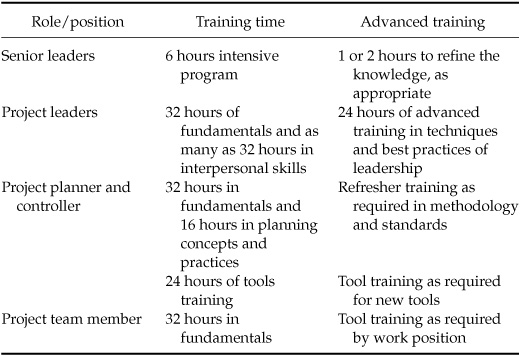

Table 2.2 summarizes the categories of people involved in projects and the level of knowledge required to effectively meet their responsibilities.

In evaluating the training requirements, it is helpful to match responsibilities, knowledge, and skill requirements to the position. A detailed analysis of an organization’s requirements is helpful to understand the type and level of training needed to improve individual’s capabilities.

A general list of knowledge and skill areas is shown in Table 2.3. It matches the training requirement to the position. This is a start point and assumes that all persons need training in the identified area.

TABLE 2.2 Responsibility—Role—Knowledge Matrix

TABLE 2.3 Knowledge and Skill Areas for Project Participants

One of the major challenges in projects is for the senior leaders to understand project capabilities and the role of senior leadership in linking projects to strategic goals. Typically, projects are initiated based on near-term requirements that may or may not contribute to the organization’s strategic position in the future. Only senior leadership can bridge the strategic to the operational areas.

Tool training is often viewed as the solution to weak project management. Training in a scheduling tool may be viewed as the only need for project leaders. However, the list in Table 2.3 clearly demonstrates the need for training in the methodology, techniques, standards, principles, fundamentals, and interpersonal skills. An effective project leader needs both knowledge and skills.

2.4.4 Developing Training Programs

Organizations need a plan for the selecting and designing training for individuals having responsibilities for project successes. Training should begin with senior leaders and cascade down to the working level of the project. This training may be accomplished in parallel rather than series. Table 2.4 suggests the type of training that may be given to individuals filling different positions.

It is important to understand that the actions of the senior leaders affect the project planning, execution, and control. Therefore, senior leaders need to understand their roles and implement the practices for linking strategic goals to projects. This prevents training project team members in their procedures and then changing the procedures to meet new guidance from the senior leadership.

TABLE 2.4 Role and Training Matrix

Referring back to the general requirements in Table 2.3, the time allocated to the training of personnel is depicted in Table 2.4.

This general outline of training provides a point of departure. An audit should be conducted to identify training requirements for each individual. What are the knowledge and skills needed for each position within an organization and what do the individuals possess? What existing knowledge is inappropriate for the organization and what retraining is required? These basic questions should guide a person in making an audit training of needs.

2.4.5 Summary

Project management training has a broader scope than just the project team. The range of training includes senior leaders and project sponsors to link their roles in the project management process with the work being accomplished. Senior leadership needs to understand the general area of projects and the indicators of progress to fulfill their strategic and operational responsibilities.

The project team, to include the project leader, needs training for basic concepts, processes and principles of project management. The training on the organization’s methodology and best practices establishes the foundation for advanced and individual needs. Selected individuals in the project team will need advanced training.

2.5 WORKING IN PROJECTS

2.5.1 Introduction

Project work is unlike much of the production work, and is unique in its execution. It usually is not repetitive, but has some difference from prior projects. Project work is stimulating and challenging to most project practitioners.

Working in projects is working with change! |

2.5.2 Understanding Project Work for the Project Practitioner

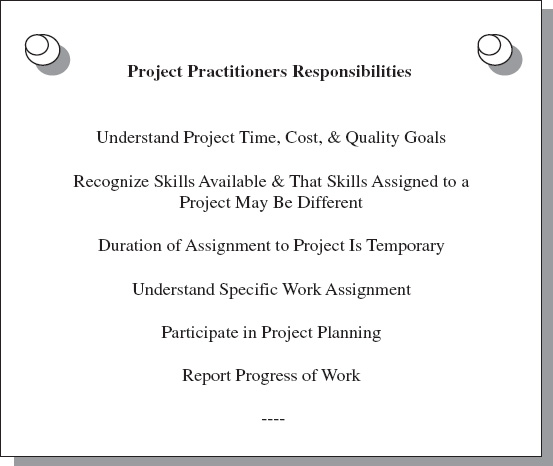

Project practitioners, whether assigned full or part time to a project, benefit from understanding the basic characteristics of the project as they relate to their responsibilities. Figure 2.8 depicts project characteristics to be understood.

FIGURE 2.8 Characteristics to be understood by project practitioners.

Characteristics of a project that affect practitioners in meeting their obligations are:

• Projects focus on goals centered on time, cost, and quality. In literature, these goals are equal. In reality, whether stated or not, these goals are ranked. Time is the most important goal, i.e., product delivery. Quality of the project’s product is second, i.e., the functionality and attributes that result from building to the design. Cost is the last goal to be considered.

• Project practitioners will receive tasks that are time constrained. Each task is dependent on receiving something and providing something to another task. This input-output process synchronizes the task with other tasks.

• Project practitioners will be assigned based on the need for skills. Often the skill requirements are not an exact match with the project practitioner. There may be greater or lesser skills. This mismatch is not a mistake; it is the way the process works and the best method available for assigning people.

When assigned to a project, recognize that there will be some difference between the skill requested and your skills. One should only raise an objection when the task cannot be completed because of a lack of knowledge. However, it is appropriate to identify the mismatch for future assignments and quality of work.

• Projects are temporary in nature. Duration of the assignment to a project can be predicted based on the need for a particular skill set. The assignment may be to accomplish one task or a series of tasks.

• Project practitioners should anticipate when they would be released from the project. Release may be to a resource pool or to another project. The goal should be to complete the current assignment as quickly and effectively as possible so as to contribute in other projects.

• Understanding the work requirement is critical to a project practitioner’s successful contribution to the project. The fast paced nature of some projects may cause miscommunication of requirements and misinterpretation of requirements.

• Project practitioners must understand the specific assignment and can confirm that by giving feedback to the project manager. Such statements as “I understand the requirement to be this” is one way of providing this feedback loop. It may be important to understand some of the background on the project. This may be obtained in a similar fashion by stating “I need some more baseline information on the project. Where may I get this information?” Ensure the task is understood prior to beginning work for the best solution.

• Project practitioners participate in project planning meetings and project status meetings. Everyone has a responsibility to understand the information being discussed and to contribute to the success of the project. There is a tendency not to raise issues if it does not directly affect the person’s individual work.

• Project practitioners have unique insight into the process and can make valuable contributions to planning and status meetings. When something is missing or going wrong, a person has a responsibility to identify the issue. This may be a missing interface specification or a leap over critical work in the project.

• Project participants will make reports of progress and status on the assigned tasks. This reporting of work accomplished is important to the project manager’s ability to accurately portray the project to customers and senior managers.

• Reporting progress with accuracy and honesty is a basic requirement. The project procedures should define the process for collecting information and reporting that information to a project control person. Some projects need progress to be measured in 10 percent increments and amount of work to complete the task in hours. Other projects require more precision such as a computed percentage by a scheduling system. When asked for future projections, ensure they are realistic.

There are other unique aspects to projects. A project participant, however, should always ensure he or she meets the assigned responsibilities by understanding the requirement, ensuring their own skill sets are capable of performing the tasks, honest and accurate reporting of progress, and closure of the assigned task. Project practitioners should anticipate when his or her assignment to the project will be completed and plan for transition to other work.

2.5.3 Understanding the Project Manager

Project managers are different in management and leadership styles. The temporary nature of a project practitioner’s assignment may limit the exposure to the project manager and may not show the project manager’s style. Longer-term assignments mean understanding what the project manager wants and how he or she expects delivery.

Being assigned as a member of the project team on a full-time basis requires that the project practitioner quickly becomes aware of the project manager’s style. Understanding this style will allow rapid assimilation into the project environment and make the project practitioner more effective. Some means of understanding the project manager’s style are:

• Observe how the project manager interfaces with others. Is it friendly or more formal? Is assigning tasks a request or an order, written or formal?

• How are meetings conducted? Rigid, free-flowing, formal, informal, tightly controlled, other?

• How enthusiastic is the project manager over the project? High energy and enthusiastic, or other?

• What communication style is exhibited by the project manager? Open, formal, informal, clear and concise, minimum information, respectful, and other? Are there mission-type instructions or detailed instructions?

• How demanding is the project manager? Expects perfection, expects timely delivery of performance and information, expects extraordinary effort on tasks, easy going and not demanding?

• What projects has this person previously managed and what were the results?

• What close associations does this person has with others, both internal and external to the project? No associations with others and considered a loner; some associations with others in a technical field; likes to associate only with people external to the organization?

Project practitioners need to know the project manager to be able to understand instructions and how to please the project manager. Often, good performance is not enough. A person needs to build relations and avoid confrontations over technical or management issues.

2.5.4 Project Practitioner’s Growth

A project practitioner has an opportunity to grow both personally and professionally while working in projects. These growth opportunities are found in rapidly changing environments that continue to challenge the physical and intellectual being of a person. Meeting the challenges exercises the mind to find new and innovative ways of doing the work.

Projects provide the environment to grow. Work is nonrepetitive and requires individual contribution to solve the problems. It is a team effort in the best sense, and through the team effort a person gains insights into others’ thought processes. Everyone contributes to the outcome of a successful project.

Personal growth is gained through working with and respecting others’ competencies. The dynamic nature of temporary assignments will expose a person to more individuals than the production type work. These contacts with others expand the number of colleagues and the network of professionals.

Many projects are on the forefront of technology, leading the industry in technological advances. Working in these projects broadens one’s knowledge of a technical field and the existing state of the art for that technology. Exposure to new technology pushes the imagination to see where and how far technology may advance in the next 10 years.

In many situations, people have infrequent opportunity to communicate with different groups. In projects, project practitioners may be required to brief customers, senior managers, and others on their work. This drives a person to improve communication skills and gives the opportunity to make both information and decision briefings. A person learns better communication methods in fast moving situations.

Projects provide opportunities for project practitioners to be recognized for their work and contributions. The project team will acknowledge the work and, if exceptional, senior management will learn of the contribution. There may be plaques and certificates to recognize and publicly acknowledge a person’s contributions.

Last, the knowledge and skills learned while in projects will build on a project practitioner’s capability for future opportunities. The project practitioner will learn more and faster in the fast-paced environment of projects when there is total involvement in the work. Involvement in solving problems while performing the work will give a new depth to an individual’s understanding of the organization’s business.

2.5.5 Summary

Most people working in projects are not trained in project management techniques, but are individuals who perform selected elements of the project’s work. These individuals are project practitioners, i.e., those who bring skill sets other than project management and who may have little experience or understanding of project management. Getting started in the project may be difficult for the project practitioner.

Individuals assigned to projects have the expectation that their skill sets will be used. Assignments are made to be a “best fit,” which does not always mean a good fit.

General skills that project practitioners will need are communication skills, progress measurement and reporting skills, and interpersonal skills. These “soft skills” may not be present in all individuals and may require some team work to help the newly assigned project practitioner.

Specific skills that may be useful in a project environment are analytical skills to assess problems, problem solving skills for finding the best solutions, and research skills to collect objective information.

2.6 PROJECT OFFICE

2.6.1 Introduction

The project office is coming into use in many organizations to achieve the benefits of consolidation for many project management functions. Centralization of the functions permits an organization to gain consistency in practices as well as using common standards for such items as schedules and reports. Benefits derived from the project office are dependent on the functions, structure, and resources assigned.

A project office is typically started to reduce the cost of project management functions in an organization and improve the quality of project information provided to senior management. The actual implementation of the project office, however, achieves benefits that extend beyond this component. One of the primary benefits is that senior management receives uniform reports for decision making. Consistency for the organization, as well as all projects, provides a greater project management capability for the organization.

A project office is a support group that provides services to project managers, senior managers, and functional managers working on projects. The project office is usually not a decision-making body that replaces either senior managers or project managers. It does prepare information and reports, however, that support the decision-making process used by senior and project managers.

A project office may also be called by several different names. Some of the more common names are:

• Project support office

• Program support office

• Project management office

• Project management support office

• Program office

2.6.2 What Is a Project Office?

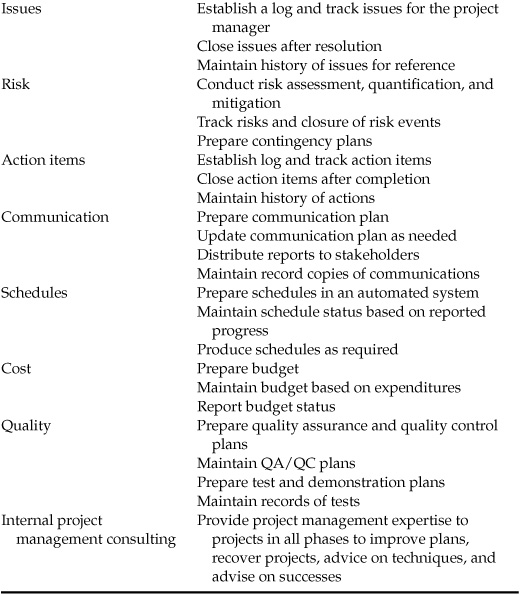

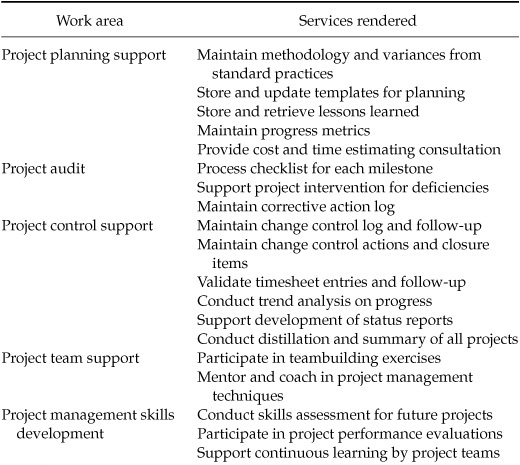

A project office is what an organization wants it to be. It can be as simple as a few people preparing and maintaining schedules to several people performing planning, reporting, quality assurance, collecting performance information, and functioning as the communication center for several projects. The project office is defined by the business needs for the organization and grows with those needs. Functions that a project office performs are shown in Table 2.5.

There are other functions that may be included in the project office. Determining whether the new items can be more effectively managed by the project manager is the criterion. One should not include items in the project office that do not directly support the projects.

2.6.3 Examples of Project Offices

Two project offices started within major organizations, one an energy company and the other a software company, reflect the differences in organizational needs. The energy company had a need to establish a project office to manage new and maintenance projects. The project management capability at the start was low because of the lack of formalized training for the project managers, few procedures because the company had recently reorganized, few techniques and practices because the former organization was distributed across several states, and weaknesses in organization practices that negatively impacted projects. A consultant was hired to form the core of the project office and provide scheduling support.

TABLE 2.5 Functions Performed by the Project Office

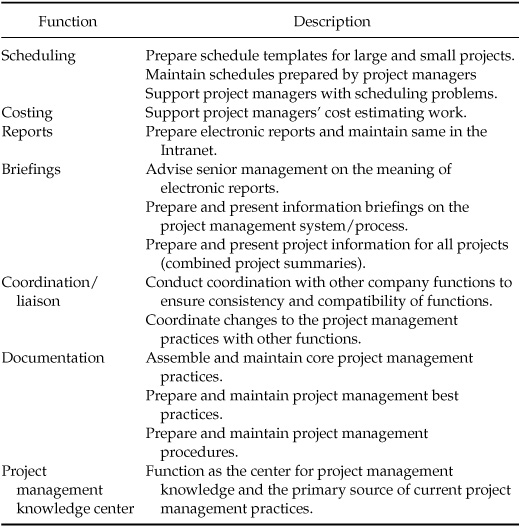

Over time, the project office assumed the role of coordinator with other business functions such as marketing, contracting, finance, and warehousing. Senior management saw the need for expanding the project office functions as depicted in Table 2.6.

This project office functioned very well in an environment that was initially at a low level of project management maturity. The willingness of the senior managers, project managers, and functional department managers to change to better management practices was probably the greatest factor in the successful implementation of a project office. The skills and knowledge of the consultant who established the project office was also a major contributor to gaining the confidence of those being supported.

TABLE 2.6 Project Office at an Energy Company

The software company’s project office was less ambitious and the scope of the project office was less than the energy company’s efforts. The primary difference being that the energy company started from little formal project management activity and the software company had an ongoing more formal project management capability. The software company, however, was not consistent in its practices and used project managers in technical and scheduling roles. The software company was attempting to change from random practices to uniform practices. Senior management did not understand their need for project management.

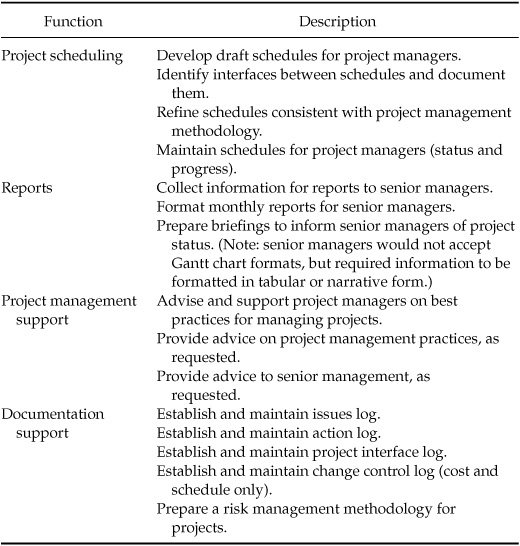

TABLE 2.7 Project Office at a Software Company

The software company established a project office with four consultants with the goal of transferring the work to internal employees. Functions planned for the project office are listed in Table 2.7.

This project office was challenged for several reasons. Senior management did not understand the functions of a project office and did not support changes to current practices by project managers. Several project managers viewed the project office as a hindrance to their practices as well as a threat to their jobs. Most of the project managers were well qualified in technical skills, but were familiar with only basic scheduling skills.

Resistance to change resulted in the project office being reduced from four consultants to three, then to two and finally one. The last functions performed by consultants were primarily administrative in nature while other functions were performed by one employee. The project office provided minimum services to the organization and in the end served more as an administrative office than a source of project management services.

2.6.4 Project Office Implementation

Starting a project office and moving it into a mature capability for an organization requires several steps. These steps are:

• Define the services to be provided by the project office. Get senior management and project manager agreement on the services. The initial project office may evolve, but it is important to have an agreed upon scope of work.

• Define the staffing skills and roles for the project office personnel. The skills and roles of the assigned personnel will determine the amount of support that can be provided.

• Establish and announce the start of the project office. Have a plan for early successes in supporting project managers and senior managers. Celebrate the early successes.

• Work closely with senior and project managers to understand their needs and meet those needs. As project managers are relieved of the routine work that the project office performs, additional requirements may emerge.

• Grow the project office’s services through continually meeting business needs while providing services to the project managers.

• Refine the skills and roles of the project office as involvement continues with the customers of the project office.

• Deliver only the best products to customers.

The project office must have the support of senior management for initiation. Success of the project office will be determined by the customers. Customers are those individuals receiving products and services from the project office. The primary customers are:

• Senior managers

• Project managers or leaders

• Project team members

• Functional managers

• Stakeholders such as the recipient of the projects’ products

Implementation is top down for the authority to start and maintain the project office. The continuation of the project office as a viable entity of the organization is determined by the customers. If the customers are not pleased with services, senior management’s support will erode and the project office will be discontinued.

2.6.5 Summary

A project office serves the business needs of the organization and relieves project managers of routine tasks. Project offices also serve the needs of executives in information gathering and formatting to understand the progress being made on projects. The project office is defined by the organization to meet the business needs of the organization and to further the business goals. Extraneous functions should not be included in the project office unless they directly support the projects.

The consolidation of several functions of project management brings about consistency in practices as well as application of project management standards. This consolidation can bring about more efficiencies as well as better products to support the projects. The consolidation of functions does not take away the decisions for senior of project managers. The products of the project office support those decisions.