SECTION 6

PROJECT INITIATION AND EXECUTION

,

6.1 Project Selection Considerations

6.3 Legal Considerations in Project Management

6.5 Developing Winning Proposals

6.8 Project Contract Negotiations and Administration

6.1 PROJECT SELECTION CONSIDERATIONS

6.1.1 Introduction

Selecting projects for an organization is important because of competing requirements and the need to bring the most value to the organization. Selecting projects for the business is critical to ensure continuity of the organization in a profitable mode. Random methods typically will not optimize the projects being pursued and will not enhance the organization’s growth.

Internal project selection is often a random process that uses ideas generated by the marketing department or managers with needs for better capabilities. These ideas often do not have the payback capability or are optimistic in the outcomes and results. Developing projects may require that some brainstorming techniques are used, but the most benefit should be gained through a better selection process.

External projects, or projects that are a part of the organization’s business, also require a structure for selection. Random bidding or accepting projects because it is work and may generate a profit are inherently counterproductive in the strategic position. A focused business plan that provides guidance as to project selection and criteria will enhance an organization’s long-term position.

Selection criteria are needed for both internal and external projects. |

6.1.2 Internal Project Selection Process

Selecting internal projects is as important as selecting external projects. The criteria are different and the selection process most often differs. Internal projects typically do not have as much weight on financial gain and more on enhancing the organization’s capability.

Internal projects are typically an investment in the organization. Investments can come in many forms and the criteria for selecting internal projects may be unique to an organization. Some criteria that have been used in the past are listed below in no rank or specific order:

• Enhance organization’s image. Example: hosting a picnic for handicapped children to demonstrate the organization’s commitment to social issues.

• Enhance the productivity of a department. Example: streamlining a process for document management, both storage and retrieval.

• Optimize operations. Example: move a department to a location closer to its customer.

• Develop a new product or change an existing one. Example: upgrade software that is used internally for producing drawings.

• Develop a new marketing strategy. Example: change emphasis on new methods of doing business.

• Strategic prerequisite. Example: need to implement strategic project that depends on information technology, such as E-Commerce.

The cost of each must be assessed for affordability, payback time, contribution to the organization’s profit or cash flow. It may be difficult to assess the cost and benefit of each project, but the process for evaluating and selecting projects needs rigor.

6.1.3 External Project Selection Process

External projects are the source of revenue for many organizations. The organization’s business is based on bidding for and executing projects that generate revenue streams and a profit. Selecting the appropriate projects is often critical to the growth of an organization because it is in the project delivery mode.

Organizations may start small and grow with the performance of projects over a matter of years. The bidding process is key to winning contracts, but first the type of contract being proposed is important. Winning contracts that an organization cannot deliver or detracts from the core business can cause an organization to fail to meet its goals.

Organizations should first determine the business that they desire to compete in and within that business line, identify the core competences. Three to five core competences may be the best for an organization to pursue because of the requirement for selected skills, similar processes, and consistent management capability. More than five core competences may defuse the efforts of small to medium organizations.

General selection criteria for external, revenue-generating projects would be similar to the following:

• Matches the organization’s core competences.

• Requirements are within the skills and knowledge of the staff or new resources that may be hired.

• Technology requirements are within the capability of the organization.

• Management processes are capable of handling the project.

• The project contributes to the organization’s public image and business image.

Other specific criteria may be applied to project selection based on the organization’s business dynamics. For example, an organization may be extracting itself from certain types of projects or from a business line for lack of sufficient margin. These projects would not be bid or bids would be priced to make sufficient margin for continuation of the line.

6.1.4 Other Considerations for Project Selection

Although a project manager is usually not directly involved in the selection process of projects to support enterprise purposes, he/she should have a general understanding of some of the approaches that are used to determine which project to initiate. Senior managers have the responsibility to make the selection of such projects regarding:

• New or modified products

• New or modified services

• New or modified organizational processes to support product and service strategies

• Projects that are used to do basic and applied research in a field of potential interest to the organization

TABLE 6.1 Project Selection Questions

• Will there be a “customer” for the product or service coming out of the project? |

• Will the project results survive in a contest with the competition? |

• Will the project results support a recognized need in the design and execution of organizational strategies? |

• Can the organization handle the risk and uncertainty likely to be associated with the project? |

• What is the probability of the project being completed on time, within budget, and at the same time satisfying its technical performance objectives? |

• Will the project results provide value to a customer? |

• Will the project ultimately provide a satisfactory return on investment to the organization? |

• Finally, the bottom-line question: Will the project results have an operational or strategic fit in the design and execution of future products and services? |

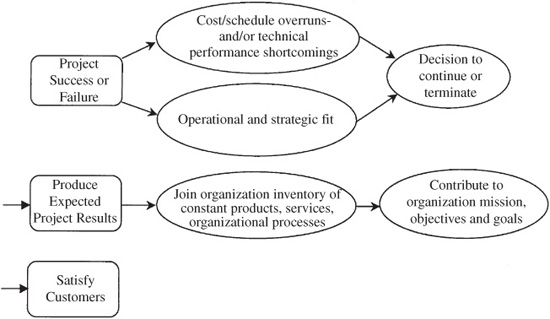

A major concern of the senior managers should be to gain insight into the promise that projects hold for future competition. Senior managers, in their evaluation of projects, need to find answers to the questions outlined in Table 6.1.

As the senior managers consider the alternative projects that are already underway in the organization, as well as new emerging projects, the above questions can help the review process and facilitate the making of decisions for which senior managers have the responsibility.

In addition, as senior managers review and seek answers to these questions, an important message will be sent throughout the organization: Projects are important in the design and execution of our organizational strategies!

6.1.5 Strategic and Operational Fit

Senior managers of an enterprise are expected to act as a team in selecting those projects whose probable outcome will enhance the competitiveness of the organization. Managers need to be aware of the general nature of project selection models and processes.

There are two basic types of project selection models—numerical and qualitative. The numerical model uses numbers to indicate a value that the project could have for the organization, whereas the qualitative uses subjective perceptions of the value likely to be created by the project.

Project selection models do not make decisions, people do. Such models can provide useful insight into the forces and factors likely to impact the value that the project can provide to the organization. However sophisticated the model, it is only a partial representation of the factors likely to impact the selection of a project. A selection model should be easy to calculate and easy to understand.

6.1.6 Other Factors

The factors to consider in the selection of a project will differ according to the organization’s mission, objectives, and goals. In addition to the above questions that need to be asked about the project, other factors can serve as a starting point:

• Anticipated payback period

• Return on investment

• Potential contribution to organizational strategies

• Support of key organizational managers

• Likely impact on project stakeholders

• Stage of the technical development

• Existing project management competence of the organization

• Compatibility of existing support by way of equipment, facility, and materials

• Potential market for the project results

Managers should use some techniques to facilitate the development of data bases to facilitate the decision process, such as:

Brainstorming—or the process of getting new ideas out by a group of people in the organization.

Focus groups—where groups of experts get together to evaluate and discuss a set of criteria about potential projects, and make recommendations to the decision makers.

Use of consultants—to provide expert opinions concerning the potential of the project, such as the availability of adequate technology to support the project technical objectives.

6.1.7 Project Selection Models

The use of appropriate numerical and qualitative models is dependent on the information available, the competence of the decision managers to understand that information, and their ability to understand what the project-selection models can do. There are a few selection models that can be used to guide the decision about project selection made by the managers.

Qualitative methods—when there is general information that can be used in the model.

Q-Sort—technique to rank-order projects based on a preselected set of criteria.

Decision-tree model—where a series of branches on the decision tree are used to determine which project best fits the needs of the enterprise.

Scoring models—when sufficient information is available about the potential value of the projects to the organization.

Payback period—used to determine the amount of time required for a project to return to cash flow equal to the amount of the original investment.

Return on investment—where an evaluation of a potential project indicates a given level or rate of return.

Other approaches are available which occur as the result of an emergency need such as:

• A senior manager’s “pet” project

• An operating requirement which can be resolved only through the introduction of new facilities, equipment, or materials

• A competitive need to meet or exceed the competitor’s performance in the market place

• Extension of a successful product or service capability

6.1.8 Financial Considerations of Project Selection

All projects must contribute to the financial health of the organization, or a management decision made to pursue a specific project for good reason. There are many reasons for pursuing projects that either will show no profit or a loss. Some of these reasons include:

• The project is bid to obtain experience in that field. This builds on the organization’s capability through some loss of profit.

• The project is bid to keep key technical staff employed. An organization may have a gap between work and a project that has no profit can be used to retain and pay the key technical staff. A temporary layoff could lose that capability.

• The project is bid because the organization knows the offer or will change his/her mind on the requirements. This project will be a profitable effort because the changing requirements will also result in increased expenditures. The project is initially viewed as a loss if the requirements are the same. The organization is at risk to provide the original requirements, but is betting on a change.

• The project is bid to become aligned with a major organization or to establish a basis for follow-on business. This project will typically establish the capability of the organization and position for new work that is profitable. There may also be benefits in demonstrating an alliance with a well-known organization.

Financial return and profit are the typical indicators of success for selecting projects. Each project is reduced to a cost and the financial return that the project will bring. There are simple and complex methods of measuring the value of a project. It is recommended that the simplest form of value measurement be used and that the complex methods only be used when required.

Return on investment (ROI) is the most common approach to earnings analysis. The earnings before interest expense and taxes are related to the total investment are used in calculating ROI. ROI measures the return in money related to all project expenses. This is simply stated as:

Total project revenues divided by all costs to complete the project.

For example, (anticipated) project revenues equal $1,500,000 and total project costs are $1,200,000. The ROI is thus $1.5 million divided by $1.2 million, or $1.25 million. This measure that shows an ROI greater than 1 yields a profit while less than 1 is a loss.

ROIs may be used to compare similar projects as a potential measure of profitability and become a useful tool in the project selection process. It permits comparison of dissimilar projects on a common scale as it contributes to the organization’s financial health.

Internal rate of return (IRR) is another approach to calculating the rate of return for a project. IRR incorporates the concept of net present value (NPV). IRR more accurately reflects the value of a project when there is a long-term project and the payment is in the future.

NPV calculates the value of money today that is paid in the future. For example, $100 earned and paid today is worth $100. If the $100 is earned today and paid in one year, an inflation rate of 3 percent would decrease the payment value by $3, or a payout of $97.

The IRR approach on a project would look at the cost of the project at various time periods and calculate the net present value of each expenditure period. Then the payments would be calculated to reflect the NPV. A comparison of the period expenditures with payment schedules would provide the information to compute total IRR.

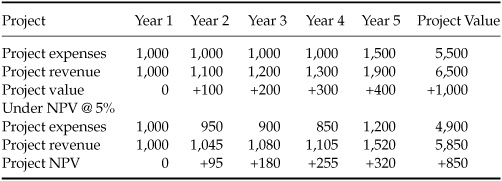

An example is shown in Table 6.2 for comparison of a project over 5 years demonstrates the concept. The nondiscounted version shows the simple approach to determining the ratio. The discounted version incorporates NPV to obtain the IRR. Long-term project values may need to be calculated by the NPV method for IRR just to make a realistic comparison. Short-term project values may not have the need when inflation rates are low.

TABLE 6.2 Net Present Value for Projects

The table shows the difference between using a simple expense-payment approach and the NPV calculations with a 5 percent discounting per year. Note that the first year is not discounted in this example, although some organizations will use a discounted rate for each year.

NPV discounts expenses and funds received in future periods. The monetary value of a project is less than the computed amount when using the NPV and computing an IRR. The nondiscounted version of Project A gives a ratio of 1 to 1.18. The NPV discounted version, or IRR, gives a ratio of 1 to 1.19. Higher discount rates, deferred payments, and a different expense or payment profile would distort the ratio significantly.

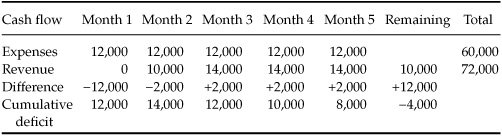

Cash flow analysis is another useful tool to determine whether a project should be selected. An organization with little capital operating in a period of high interest rates may need to perform a cashflow analysis. This will determine the amount of money required for expenses and the payment schedule for a project.

Cash flow is typically computed on a monthly basis where a project’s expenses are estimated to determine the outward flow of money and the estimated payments each month from the project. A 5-month project, for example, could have an expense to revenue profile as shown Table 6.3.

The project will require financing between $8,000 and $14,000 during its life. This profile of more expenses than revenues throughout the life of the project dictates that financing be obtained to support the difference. Project selection must consider the need for additional funds and the cost of those funds during the project life.

6.1.9 Summary

Project selection is more than identifying an idea or finding a profitable venture that contributes to the organization’s financial health. Projects must fit within the core competences of the organization and bring benefits to the organization. Random project selection practices may deliver the wrong benefits and suboptimize the organization’s project capabilities.

Using the simplest approach to select projects is best and ensures all pertinent factors are considered. Having criteria for selecting projects provides an objective structure for sorting through numerous choices. First, the project should fit the organization’s strategic goals and bring benefits to the organization. Secondly, the project must bring financial benefits to the organization. Financial benefits should be assessed through one or more approaches such as ROI, IRR, and cash flow analysis.

6.2 PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY

6.2.1 Introduction

A project feasibility study is accomplished when there is reason to believe an idea or request for proposal has merit and can provide an opportunity to initiate a project. It is an examination of the viability of a project and its ability to provide a value greater than the effort or resources consumed. Typically, it is a general view of a concept that may or may not prove to be feasible for an organization.

Feasibility studies may be used for many different purposes, but in this section focuses on the business attributes of a future project. The study results in a recommendation to either choose an alternative or to not pursue the project. Selection of the best of say three alternatives may not produce the desired results and, therefore, the project would not be a viable option.

Feasibility studies should always be conducted prior to the start of a project. Once an investment is made in a project, it is more difficult to justify termination because of the expenditure. Once a project is started, however, it may be necessary to validate that the situation has or has not changed to justify continuation or termination. These follow-on feasibility studies may be used to validate continuing on the course of action, recommending an alternative course of action, or termination of the project.

6.2.2 Common Factors of a Project Feasibility Study

There are several common factors that need to be included in a study of project viability to ensure all facets are addressed. This allows assessment of the potential of an idea or proposal in a comprehensive manner to ensure a valid study. These factors are as follows:

• Technology and system integration—the availability of technology to solve the problem posed by the idea or proposal and the capability to integrate the parts of the system. This is a review of the technology available or within the organization to solve the proposal.

• Economics—the cost versus benefit derived from conducting the project. Typically, this is a calculation of the price of doing the project compared to the value of the completed product.

• Legality—the ability to produce the project’s end result without violating any law, such as copyright or patent infringement, and the product operates within the bounds of the law in such areas a health and safety. Other legal requirements may apply for special purpose products, e.g., protection of personal information for data handling machines.

• Operation—the ability of the proposed product to solve the problem presented by the idea or proposal. Any product considered must solve the problem or it is not a feasible solution.

• Time—the time frame in which a feasible solution can be used before the product would become obsolete. A solution taking too long to develop may be overcome by events and the problem has taken on new dimensions.

6.2.3 Preparing the Feasibility Study

Procedures for preparing a feasibility study should follow a standard practice to ensure coverage of all areas. The following steps are suggested as a basic format:

• Define the idea or request for proposal. This step is critical to understand the idea or request for proposal. It is important to ensure the true concept and get agreement with the tasking party. Getting agreement with the senior manager ensures that one is working in the right direction to conduct the feasibility study. Document the agreed upon statement.

• List facts and assumptions. Following the definition of the concept, one needs to list all the available related facts. Where facts are not available, list assumptions needed to complete the study. Facts are true elements while assumptions are anticipated true elements of the future. List all the facts and assumptions separately.

• Develop possible solutions. Using the common factors of a feasibility study, develop solutions to the problem of whether the concept is feasible. This initial development brings the issues into focus and brings a sharper image of the problem. It also identifies areas where insufficient information is available and must be collected to flesh out the solutions. Although brainstorming may be used to develop possible solutions, they must be documented.

• Research and collect information. Using the solutions developed above, research and collect additional information that relates to the concept. Fill in the voids and bridge the gaps found while developing solutions to the problem. Note where there is insufficient information available to continue with a solution after conducting the research. Document the pertinent information and where there is insufficient information.

• Analyze the information. Analyze the collected information to ensure that it is valid and pertinent to the concept. Invalid information can lead to the wrong conclusions—and a wrong solution to the problem. Document the analysis methods used for later reference.

• Develop alternative solutions. Refine the developed possible solutions and develop alternatives that could solve the problem. Ideally, it is best to have three or four solutions. Too many solutions probably indicate some are near duplicates and too few indicate a limited scope of the study. Document the new alternative solutions.

• Evaluate alternatives and develop conclusions. Compare the alternatives to determine whether there are duplicates. Eliminate duplicate solutions using the same information and facts. Winnow the number of possible solutions to less than five, with at least one solution being that the project is not feasible. Draw some conclusions from the comparisons and document them.

• Select the best alternative and recommend a solution. Rank the solutions and select the one with the most potential. This may result in a recommendation that the project is not feasible within the constraints identified in the analysis. It may also result in a solution that is high risk in one or more of the common factors of a feasibility study. A single recommendation should be made with justification for the solution.

A well-done feasibility study is a clear path to solving the problem or issue that is presented in the definition part. One should check to see whether the logic of statements or there are missing parts that cause a gap in the study. Documenting information throughout the process allows a person to review the process for validity and traceability of actions.

6.2.4 Common Problems of Feasibility Studies

Some common problems found with feasibility studies may be identified by asking the following questions before, during, and after development. These questions should cause one to think through the actions and development process.

• Is the issue too broad to be able to define clearly?

• Is the issue properly defined and stated in written form?

• Are facts and assumptions clear and valid?

• Are there any unnecessary facts or assumptions that are not related to the issue or concept?

• Are there sufficient facts and assumptions to conduct the study?

• Is the discussion of facts, assumptions, and information too long?

• Is there enough information collected to justify the conclusions?

• Do conclusions follow the analysis?

• Are there a limited number of options or courses of action—typically three to five?

• Are assessment criteria invalid or too limited?

• Do the conclusions include a discussion?

• Do the conclusion and recommendations answer the issue statement?

6.2.5 Format for a Feasibility Study

A sample format for a feasibility study is provided for use as a guide in the development and reporting the results. This format may be modified to accommodate the actual study.

SUBJECT: Briefly describe the study’s contents here.

1. Problem. Write a concise statement of the problem, stated as a task, in the infinitive or question form; for example, To determine the feasibility of. . . . normally include the who, what, when, and where if pertinent.

2. Background. Provide a lead-in to the study, briefly stating why the problem exists.

3. Facts. State facts that influence the problem or its solution. Make sure the facts are stated and attributed correctly. The data must stand alone; either it is a clear fact or is attributed to a source that asserts it true. There is no limit to the number of facts. Provide all the facts relevant to the problem (not just the facts used to support the study). State any guidance given by the authority directing the study. Refer to annexes as necessary for amplification, references, mathematical formulas, or tabular data.

4. Assumptions. Identify any assumptions necessary for a logical discussion of the problem and augmentation of the facts. If deleting the assumption has no effect on the problem, you do not need the assumption.

5. Courses of action. List all possible suitable, feasible, acceptable, distinguishable, and complete courses of actions. If a course of action (COA) is not self-explanatory, include a brief explanation of what the COA consists of to ensure the reader understands. If the COA is complex, refer to an annex for a complete description (including pertinent COA facts).

a. COA 1. List specifically by name, for example, complete project integration.

b. COA 2. Same as above.

c. COA 3. Same as above.

6. Criteria. List the criteria used to judge COAs. Criteria serve as yardsticks or benchmarks against which to measure each COA. Define criteria to ensure the reader understands them. Be specific. For example, if using cost as a criterion, talk about that measurement in dollars. Use criteria that relate to the facts and assumptions. There should be a fact or an assumption listed in paragraph 3 or 4, respectively, that supports each of the criteria. The sum of the facts and assumptions should at a minimum be greater than the number of criteria. Consider criteria in three related but distinct areas, as indicted below.

a. Screening criteria. Define screening criteria that a COA must meet to be suitable, feasible, acceptable, distinguishable, and complete. Accept or reject a COA based solely on these criteria. Define each criterion and state the required standard in absolute terms. For example, using cost as a screening criterion, define cost as dollars and specify the maximum (or minimum) cost you can pay. In subsequent subparagraphs, describe failed COAs and state why they failed.

b. Evaluation criteria. This is the criteria used to measure, evaluate, and rank-order each COA during analysis and comparison paragraphs. Use issues that will determine the quality of each COA and define how to measure each COA against each criterion and specify the preferred state for each. For example, define cost as total cost including research, development, production, and distribution in dollars—less is better; or cost is manufacturer’s suggested retail price—less is better. Establish a dividing line that separates advantages and disadvantages for a criterion. An evaluation criterion must rank-order COAs to be valid. Some criteria may be both screening and evaluation criteria, such as, cost. You may use one definition of cost; however, the required or benchmark value cannot be the same for both screening and evaluation criteria. If the value is the same, the criteria will not distinguish between advantages and disadvantages for remaining COAs.

(1) Define evaluation criteria. Each evaluation criterion is defined by five elements written in paragraph or narrative form.

• A short title (cost, for example)

• Definition (the amount of money to buy . . .)

• Unit of measure (for example, U.S. dollars, miles, acres)

• Dividing line or benchmark (The point at which a criterion becomes an advantage. Ideally the benchmark should result in gaining a tangible benefit. Be able to justify how you came up with the value—through reasoning, historical data, current allocation, averaging.)

• Formula [Stated in two different ways. That more or less is better. ($400 is an advantage, >$400 is a disadvantage, less is better) or subjectively in terms such as a night movement is better than a daylight movement.]

(2) Evaluation criterion #2. Again define and write the criterion in one coherent paragraph. To curtail length, do not use multiple subparagraphs.

(3) Evaluation criterion #3, and so on.

c. Weighting of criteria. Establish the relative importance of one criterion over the others. Explain how each criterion compares to each of the other criteria (equal, favored, slightly favored), or provide the values from the decision matrix and explain why you measured the criterion as such. Note: Screening criteria are not weighted. They are required absolute standards that each COA must meet or the COA is rejected.

7. Analysis. For each COA, list the advantages and disadvantages that result from testing the COAs against the stated evaluation criteria. Include the payoff value for each COA as tested. Do not compare one COA with the others (that is the next step). Do not introduce new criterion. If there are six criteria, there must be six advantages or disadvantages (as appropriate) for each COA. If there are many neutral payoffs, examine the criteria to ensure they are specific and examine the application of the criteria to ensure it is logical and objective. Neutral should rarely be used.

a. The first subparagraph of the analysis should state the results of applying the screening criterion if not already listed in paragraph 6a(2). List screened COAs as part of paragraph 6a for clarity and unity.

b. COA 1. (List the COA by name.)

(1) Advantage(s). List the advantages in narrative form in a single clear, concise paragraph. Explain why it is an advantage and provide the payoff value for the COA measured against the criteria. Do not use bullets; remember, the paper must stand alone.

(2) Disadvantage(s). List the disadvantages for each COA and explain why they are disadvantages. Include the payoff values or how the COA measured out.

c. COA 2.

(1) Advantage. If there is only one advantage or disadvantage, list it as shown here.

(2) Disadvantage. If there is no advantage or disadvantage, state none.

8. Comparison of the COAs.

a. After testing each COA against the stated criteria, compare the COAs to each other. Determine which COA best satisfies the criteria. Develop for the reader, in a logical, orderly manner, the rationale you use to reach the conclusion in paragraph 9 below. For example, Cost: COA 1 cost less than COA 2, which is equal to the cost of COA 4. COA 3 has the greatest cost.

b. You can use quantitative techniques (such as decision matrixes, select weights, and sensitivity analyses) to support your comparisons. Summarize the results of these quantitative techniques clearly so that the reader does not have to refer to an annex. Do not e x plain the quantitative technique, simply state what the results are. Remember, quantitative techniques are only tools to support the analysis and comparison. They are not the analysis and comparison.

9. Conclusion. Address the conclusion drawn from analyzing and comparing all the relevant factors (for example, COA 2 is the best COA because. . .). The conclusion must answer the problem statement. If it does not, then either the conclusion or the problem statement is incorrect.

10. Recommendation. Recommend a specific course of action (who, what, when, and where). The recommendation must solve the problem. If necessary or directed, place an implementing document as an attachment.

(Adapted from U.S. Army Field Manual 101-5, Staff Organization and Operations, Headquarters, Department of the Army, 31 May 1997.)

Note that this format is for a major decision-making operation. Smaller, short-term projects may use an abbreviated portion of this format. All items, however, should be covered is summary style.

6.2.6 Summary

This section gives some suggestions for the preparation of a feasibility study to determine whether a project should be initiated (or continued) based on available facts and information. There are considerations listed that are helpful in determining whether a valid feasibility study has been conducted as well as a format to guide one in the development of the study.

6.3 LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

6.3.1 Introduction

Project management is like any other management challenge. There are many laws, regulations, protocols, and conventions that have emerged that conditions the project manager’s authority in managing the project. Disputes concerning the project can delay, increase schedules or costs, or even result in the cancellation of the project. The project manager has access to a legal system in the United States, which usually provides a comprehensive framework that can guide the planning, and execution of a project.

6.3.2 The Legal Framework

The new project manager should recognize the potential for legal relationships that could impact the project. There are some specific agreements relative to the project that require particular attention and consideration such as:

• Contractual agreements with customer(s) and vendors.

• Internal work authorization initiatives that provide for the delegation of authority and the transfer of funds to perform work on project work packages. Although these agreements are not “contracts” per se, if care is taken to negotiate agreements with internal organizations of the organization, the chances are enhanced that they will more fully support the project.

• Relationships with project partners, such as a joint venture.

• Funding agreements in the case of a project that is funded externally. Because the lender or giver of funds has assumed considerable risk, control over the management may be desired, such as an increased role over the use of funds on the project.

• Regulators, whether local, state, or federal, are key stakeholders of the project. The roles and expectations of these stakeholders should be determined as soon as possible, to include definition and agreements for the legal relationship that is expected.

• Project insurers can provide for the reduction of the risks expected on the project. In seeking protection from an insurer, the project manager should carefully negotiate the coverage, limits and liabilities, responsibilities and authorities of the participants, and the means to be used for determining damages, if incurred.

• Licensing agreements involves the use of proprietary technology or other property rights.

• Other stakeholders, such as those defined in Sec. 4.4, who have or believe that they have some right or share in the manner in which resources are used on the project. These rights or shares are discussed in that section, and will be mentioned here only as a brief reminder:

• Governments

• End users of the project results

• Competitors

• Investors

• Intervenors or interest groups

• Employees

• Unions

Some of these stakeholders hold a contract with the organization that is sponsoring the project. For example, the employment contract held by employees is conditioned by nondiscrimination statutes, and the collective bargaining contract with the union. All of these contracts may restrict the project manager’s ability to assign employees to work on the project because of the potential of a lawsuit.

There are many complex, encompassing legal issues in which the project manager can become embroiled.

To guard against putting the project or some of its stakeholders at risk of legal action, the project manager and his/her team should seek an early and continuing relationship with the organization’s legal office. In our personal lives, the best time and manner to use lawyers is before we get into trouble! It is no different in project management.

6.3.3 The Contract Structure

Because the success or failure of the project usually centers on cost, schedule, quality, and technical considerations, the performance standards in these areas must be established early in project planning. There are four basic contracts, which the project manager can use:

• Fixed-price contracts—in which the contractors agree to execute a particular scope of work in a defined time period for a specified price.

• Cost-reimbursement contract—used when the scope of work is not well-defined, the buyer assumes most of the risk in cost, schedules, and technical performance objectives. Normally these contracts will be reimbursed for all of their costs plus a percentage fee.

• Unit-price contracts—in which the buyer assumes all risk of changes in the scope, costs, and schedules of the project, and the contractor assumes the risk that the cost of performing a unit of work may be greater than estimated.

• Target-price contracts—in which the contracting parties establish cost and schedule standards with accompanying rewards and penalties for the seller of products or services.

There are variations for these types of contracts, as well as other specialized contracts that might be used. When the question of which contract to use, or the conditions in which it can be used, see the legal advisor! The potential for disputes in project management is always present. When disputes arise, the counsel of the local legal office should be sought as soon as possible.

6.3.4 Resolution of Disputes

• Mediation—in which a nonadjudicative process in which the disputing parties work with a neutral third party and attempt in good faith to resolve the disputes. The disputing parties are normally not bound to accept any proposed resolution by the third party.

• Arbitration—in which an impartial, binding adjudication of a dispute without resort to formal court proceedings is carried out. The arbitrator’s decision is final for all practical purposes. The award the arbitrator decides on will normally be final without resort to court proceedings.

• Litigation—a form that should be used as a last resort. When managed efficiently and effectively, litigation may be more cost effective than arbitration, since the parties do not pay the courts for the adjudicative work.

• Standing dispute-resolution board—in which a standing board is appointed at the beginning of a project to evaluate and decide disputes on a real-time basis. This form enables the resolution of disputes in a more timely manner. This type of board can be expensive, and is normally used on very large projects whose time frame extends over many years.

6.3.5 Documenting the Record

On the chance that one or more of the above forms of resolution of disputes will be needed, in addition to simply making good sense, records should be kept backing up decisions on the project. Minutes of planning and review meetings, organizational design selection, monitoring, evaluation, and control meetings should be maintained. In other words, use common sense and document the management of the project—in particular those management actions that have to do with the manner in which decisions are made and executed on the project. Certain information of a project is proprietary and should accordingly be adequately safeguarded.

If a dispute may arise, or has arisen, seek guidance from the counsel of the local legal office on how the documentation relative to the dispute should be researched and provided.

6.3.6 Project Changes

Changes to project cost, schedule, or technical performance parameters should be carefully documented and maintained for use in future disputes. The project manager should build a project change mechanism around the basic factors shown in Table 6.4.

6.3.7 Handling Potential Claims

• Be sure that all real and likely changes have been resolved before assuming that the project is a success.

TABLE 6.4 Project Change Mechanisms

• Evaluate how and when the contract changes may impact the project. |

• Authorize the change—after coordination with the relevant stakeholders. |

• Communicate the change to all concerned parties. |

• Modify the existing contracts or work agreements. |

• Near the end of the project, go through an explicit analysis, working with the project team and stakeholders, to ascertain if any claims should be instituted, or if there are any outstanding claims that need to be resolved.

• In all circumstances, see the legal counsel and obtain assistance. Keep in mind that the legal office is an office of functional experts, and like other functional entities, supports the project.

6.3.8 Summary

The project manager must understand the legal liabilities associated with the project stakeholders. All members of the project team should understand the basics of contracts, disputes, dispute resolution, and how the legal components of the project should be managed. The section closes with the admonition that the help of the local legal office should be sought when becoming involved in any legal matters involving the project.

6.4 PROJECT START-UP

6.4.1 Introduction

Getting a project started right is much easier than trying to correct erroneous expectations or redirecting the effort of the project team. For the best solution, it is always better to start with all the project team working in the same direction and committed to making the project a success. Once the project execution begins, the dynamics will keep it moving either in the right direction or the wrong direction.

Project start-up is the first opportunity to bring the entire project team into one location and have a mutual understanding as to the project, its goals, the expectations of the customer and senior management, and the relationships within the project team. This is the time for the project leader to set expectations and obtain the commitment of the individuals and the project team to the goals.

Starting a project on the right course is the first step to success. |

6.4.2 Getting Started

The first task for a project team is to build the project plan. With limited planning experience, the team must take the goals of the project and convert those to a coherent guide from start of execution through project closeout. The planning exercise is critical to obtaining commitment to the project as well as ensuring the team understands the work to be accomplished.

Project planning will require collaboration among the team members to design the solution to the problem and elaborate on the goals for the project. A typical set of tasks for the project team could be:

• Review and analyze the project’s goals and other amplifying documentation.

• Validate the project’s goals and feasibility of meeting the goals.

• Identify issues and seek resolution to them.

• Identify risks and seek mitigation options.

• Develop a product description or specification.

• Develop a work breakdown structure.

• Develop a project schedule.

• Develop a project budget.

• Develop supporting plans, including:

• Change control

• Scope control

• Risk

• Procurement

• Communication

• Quality

• Staffing

• (Other as needed)

• Obtain senior management’s approval of the plan.

Project planning by the team has become a joint effort, with some members performing parts that support the overall approach. For example, one member may write the staffing plan and another may write the risk plan. The entire team, however, reviews the final project plan for accuracy and completeness before seeking approval from senior management.

Project plans may also receive a peer review and comment. Often those who have worked in projects of a similar nature will be able to provide a critique of the plan and identify points that need clarification or special consideration.

6.4.3 Project Diary

A project diary is started on the first day of the project. The project diary is the place to record actions and activities that are informal, but have a bearing on the project. It may be viewed as a log of activities that affect the planning, execution and control of the project.

FIGURE 6.1 Example of a project diary.

The project diary is the history of many actions that may need to be reviewed and to record information that affects the project. Figure 6.1 is an example of project diary entries.

It is important to maintain the project diary for future reference. Although an informal document, it is a reference to continue follow-up on actions. Also, some issues and problems may be recurring and it is best to have a record of the number of times they occur.

6.4.4 Project Kickoff Goals

Planning a kickoff meeting should be driven by the goals that one will achieve. A kickoff meeting is not a social event where there is an exchange of pleasantries and backslapping, but it is an important launch point for the project.

Goals for the kickoff meeting should be:

• To establish the project leader as the single point of contact for the project and as the head of the project team. This includes announcing the project leader’s authority and responsibilities for the project planning, execution, control, and closeout.

• To establish the project team’s role and responsibilities for the project and obtaining commitment, individually and collectively, for the project’s success.

• To provide project background information and planning guidance. This includes all information needed by the project team to initiate the next phase of work.

6.4.5 Project Kickoff Meeting

When the project team is first assembled, it is essential that the project structure and purpose be communicated to all team members. The first meeting may be prior to the start of the planning or it may be at the start of execution. If there is a small team at start of planning and a larger team at start of execution, it may be necessary to hold two meetings.

Planning the kickoff meeting to ensure coverage of important items requires an agenda. This agenda could include all or a majority of the following:

• Set the tone and general expectations for the project team—project leader should describe the project in narrative with some graphics and describe the project’s importance to the organization. Senior management may also address the importance of the project and its contribution to the organization’s business.

• Introduce team members to each other—team members introduce themselves and state their expertise that will contribute to the project’s success.

• Set expectations on working relationships—project leader discusses his or her expectations of what the team and team members can expect from him or her. Team members state what others may expect from them.

• Review project goals—project leader reviews the project goals with the team. The goals are expanded upon in terms of whether they are fixed or subject to change for any reason.

• Review senior management’s expectations for the project—project leader reviews senior management’s requirements for the project and what the team can expect from senior management in terms of support or involvement in the project.

• Review project plan and project status—project leader reviews the status of the project and discusses any progress previously made. This is the opportunity to identify the point at which the project team will start in the project’s life cycle.

• Identify challenges to project (issues, problems, risks)—project leader identifies and challenges to the project and discusses ongoing actions to resolve them.

• Question and answer period—this is an opportunity for the project team to ask questions about the project. It is also a time to clarify any erroneous perceptions and dispel any rumors about the project.

• Obtain commitment from project team for the work—project leader asks if any member has any reservations about committing to the project and obtains commitment from all participants to make the project successful. The project leader must also make a commitment to the team and to the project.

Bringing in senior management, the project sponsor, and functional managers to acknowledge the project’s importance and say a few words may be needed. Ensuring that the entire team and all team members are committed to the project is essential to getting a proper start.

6.4.6 Follow-On to Project Kickoff

Questions or comments that affect the success of the project must be resolved soon after the project kickoff meeting. Delayed answers and avoided questions raise doubts in the project team and will typically erode commitment.

Follow-on meetings may be required when the entire team is not at the initial kickoff meeting or when the composition of the team changes dramatically through matrix management or for other reasons. If there was less than full information about the project, a second meeting should be held.

Accomplishments that represent progress following the kickoff meeting should be celebrated. For example, when the kickoff meeting is prior to planning, the completion and approval of the plan should be celebrated. This celebration is an acknowledgement that the team is working together and meeting its commitment to the project.

6.4.7 Summary

Proper project start-up is critical to the success of the project’s goals and delivering the benefits of the project to the customer. Senior management, functional managers, the project leader, and the project team have important roles to play in getting the project started right. The project kickoff meeting is typically the time that all stakeholders converge to disseminate information and demonstrate their commitment to the project’s success.

Planning the project kickoff meeting by reviewing and confirming the goals is the project leader’s responsibility. Preparing an agenda and assembling information for presentation facilitates and make for an effective kickoff meeting. When appropriate, involvement of senior management to emphasize the importance of the project to the organization and their commitment to support the project can materially add to the meeting.

Follow-on meetings and celebration of achievements are important to reconfirm to the project team the importance of their role and commitment to project success. Changes to the project or project team may dictate a need to have more than one follow-on meeting.

A project diary is part of the initiation of the project and a log for informally recording actions and activities. It is the record of daily items that can affect project success and a source of information when additional discussion or action is needed on an item.

6.5 DEVELOPING WINNING PROPOSALS

6.5.1 Introduction

Proposals are the foundation for starting projects. Successful proposals are well planned, well written, cohesive, and competitively priced. Proposals may be either to an internal organization or external to a potential customer. Proposals to external customers are more formal and comprehensive.

All proposal efforts of any size have a proposal manager and a proposal team. The team is typically an ad hoc proposal team established for one specific effort. The temporary nature of the team requires that the proposal manager be able to quickly assemble and motivate the team. A kickoff meeting that communicates the need for the proposal and its importance to the organization is the best method.

Proposals tell the potential customers how you will satisfy their needs. |

6.5.2 Planning the Proposal Effort

Winning a contract from any proposal requires a dedicated effort to develop the document for delivery to the potential customer. This development requires a disciplined approach to writing and assembling the proposal as shown in Fig. 6.2. The success of the proposal is determined by whether it conveys the proper message and commitment to performing the work.

FIGURE 6.2 Strategy for winning the contract.

First, define a strategy for winning the contract through the proposal. What is the strategy and why will it work? This strategy results from the following:

• An in-depth analysis of the customer’s stated requirements or needs

• An analysis of competitors’ offerings

• An assessment of what your organization can offer

• A decision as to how to shape your proposal for the highest probability of winning

Once the strategy has been developed by a thorough assessment of the needs, competition, and your capabilities, the winning theme for the proposal is identified. The theme is the central idea, which provides cohesion to the proposal.

Responsibility for writing the proposal is assigned based on a task list and the available specialists. There is always a need for someone to ensure the cohesive theme is contained in all writings as well as addressing the technical aspects of the customer’s needs. The proposal manager must ensure all tasks have a qualified person assigned to write a portion of the proposal.

A schedule for proposal work is needed to ensure all critical dates are met. Most schedules will include the times and durations for meetings, dates of critical milestones in preparing the proposal and delivery date for the proposal. Timing is critical when the customer sets a “no later than” date for delivery or the proposal will be rejected.

Table 6.5 shows an example of a schedule shown with the general tasks associated with preparing a proposal. This matrix of tasks includes the start and finish dates for each task as well as the person responsible for performing the task.

The schedule is important to ensuring that the proposal is delivered to the customer on time. The above example shows discrete days for assignment and delivery. However, assignments may be delivered early so the editing and integration can be started early. A technical specialist may write his/her portion in half the allotted time and deliver it to the technical editor. This levels out the work for the technical editor as well as releases the technical specialist to other work.

TABLE 6.5 Schedule of Proposal Activities

For large, complex proposals it may be necessary to make smaller steps in the writing portion. Experience levels of the writers also contribute to the ease or difficulty in preparing a proposal. Steps for a large proposal may include the following:

• Develop the strategy and theme for the proposal. The strategy and theme are based on the customer’s requirements and the competitive offerings. Strategy and theme are designed to ensure a high probability of winning the contract through the proposal.

• Develop a detailed set of customer requirements and questions to be answered in the proposal. These detailed requirements and questions must be clearly addressed and readily identifiable in the proposal.

• Develop a detailed outline of the proposal similar to the table of contents for a textbook. Ensure any customer-prescribed format is followed when developing the outline. The outline must accommodate answering the questions and requirements identified in step 2.

• Develop a writing task list for all components of the proposal. This task list should identify the skills and knowledge required of the person writing the proposal section.

• Assign smaller tasks with shorter time frames to writers. Have each writer outline in bullet form his/her tasks to ensure consistency and following the proposal theme.

• Conduct frequent reviews of the writers’ work and ensure the customer’s requirements and questions are being answered.

• Using the detailed outline, prepare the framework and complete the general requirements of a proposal.

• Start integrating writers’ contributions early and ensure the contributions are responsive to customer requirements.

• Conduct frequent team reviews to show progress and to identify written work that needs revision or additional work to clarify the proposal.

• Assemble all written work and conduct a comprehensive review with senior management to obtain approval for release. Senior management’s approval is required because the proposal is a commitment of the organization.

6.5.3 Proposal Contents

Proposals address three areas for the customer. These areas address: What are you going to do? How are you going to manage it? How much will it cost? These primary components are:

• Technical—what is being proposed and how it will be accomplished. This may be viewed as describing the work to be accomplished and the procedures used to perform the work. Another way of viewing this is “what problem is being solved and what is the approach to solving it.”

• Management—what is the proposed method for managing this project work and what other information is required to establish credibility. The customer wants to be assured the work will be well-managed for successful completion.

• Pricing—what is the proposed bid price and what are the proposed terms and conditions for payment. The customer will typically require the price information to be in a specific format that may include detailed breakout of pricing for parts of the project.

Assembling the three modules for delivery to the customer may vary significantly. Delivery may be required in one single bound document or in three separate documents. Instructions for the format and assembly will usually be in the customer’s solicitation document.

6.5.4 Technical Component of the Proposal

This component is concerned with the actual details of what is being proposed. The usual topics included are:

• Introduction—a nontechnical overview of the contents.

• Statement of the problem—a complete definition of the basic problem that will be solved with the proposed service, product, study, or other work.

• Technical discussion—a detailed discussion of the proposed service, product, study or other work being offered.

• Project plan—a description of the plan for achieving the goals of the proposed project.

• Task statement—a list of the primary tasks required to achieve the project plan.

• Summary—a brief nontechnical statement of the main points of the technical proposal.

• Appendices—detailed or lengthy technical information that contributes to the understanding of the technical proposal.

6.5.5 Management Component of the Proposal

This component is concerned with the actual details of what is being proposed for managing the project. The usual topics included are:

• Introduction—a nontechnical overview of the contents of the technical and management components.

• Project management—details of how the project will be managed.

• Organization history—a brief discussion of the developmental history of the organization.

• Administrative information—a description of the organizational structure, management, staff, and overall policies and procedures that relate to the capability to perform the project work.

• Past experience—an overview of experience of a similar nature that contributes to the project performance.

• Facilities—a description of the facilities that will be used to provide the proposed service or build the product.

• Summary—a brief restatement of the main points of the management component.

6.5.6 Pricing Component of the Proposal

This component is concerned with the details of the costs for the project and the proposed contractual terms and conditions. The usual topics included are:

• Introduction—a nontechnical overview of the main points of the technical and management components.

• Pricing summary—a summary of the costs for the proposed work.

• Supporting details—a breakout of the costs for items that appear in the pricing summary.

• Terms and conditions—a definitive statement of the proposed terms and conditions under which the product or service will be delivered.

• Cost estimating techniques used—a description of the methods used to determine the pricing in the proposal.

• Summary—a brief statement of the price of the proposed work and the major items being priced.

6.5.7 The Problem Being Solved

The most important aspect of any proposal is to identify and understand the problem that the customer is asking to be solved. Presenting your understanding of the problem and what is proposed to solve the problem is critical to being able to convince the customer that your proposal is the best one. Description of the problems usually involves:

• Nature of the problem

• History of the problem

• Characteristics of the optimal solution

• Alternative solutions considered

• Solution or approach selected

Describing the problem and the approach to solving the problem is the process of convincing the customer that you understand the situation. This area must be well stated both factually and convincingly to assure the customer that your proposal is the one to select. Identifying the wrong problem or providing subjective opinion will not convince the customer that your proposal gives the best solution.

6.5.8 Summary

Proposal writing is important to convey to a potential customer your understanding of the problem and that you have the best solution. The proposal states your technical approach to solving the problem, your management approach to the project, and the price at which you will perform the work.

Building a convincing proposal is a disciplined process that follows a general format with three components: technical, management, and pricing. The format provides the structure in which to describe your ability to meet the customer’s needs for a product or service. Completing the format to accurately communicate your capabilities and desire to perform the work is in the detail.

Winning proposals are developed by a technically competent, motivated team. The proposal manager sets the tone for the proposal development and assigns the detail tasks. Proposal managers are often involved in the details of integrating the written tasks and working with the technical editor to build a smooth flowing document.

6.6 PROJECT STATEMENT OF WORK

6.6.1 Introduction

A statement of work (SOW) is a formal, contractual document that states and defines work activities associated with a project’s contract. The SOW may relate to a contract that is the reason for the project or it may be a SOW directed at a project’s subcontractor. In either situation, the format and requirements for the document are subject to the nature of the work being preformed. The purpose of the SOW is the same: to specify How, When, and Where work will be accomplished.

There are many formats for SOWs, depending upon the type of goods and services requested. Furthermore, the type of contract used to obtain goods may affect the content of the SOW. Some suggested formats are included in this section for consideration

6.6.2 Topics within a Generic SOW

Topics typically included in the SOW are listed below. These topics may be elaborated in great detail or in summary fashion—depending upon the amount of control the requesting organization wants to exercise over the performing organization.

• Scope of work—describes the work to be accomplished in detail and specifies the precise nature of the work to be accomplished.

• Location of the work—describes where the work will be performed. It is the place for conduct of all work.

• Period of performance—sets forth the time frame for the conduct of the work and is typically a specific start and finish time.

• Deliverable schedule—sets forth the delivery of goods and services by describing what and when they will be each will be handed over.

• Applicable standards—specifies which standards must be adhered to in fulfillment of the contract.

• Acceptance criteria—sets forth the criteria by which the goods or services will be measured for acceptance at time of delivery.

• Special requirements—sets forth a required special hardware or software, any special workforce requirements (e.g., degrees, certifications, or security clearances), and anything else not covered in the contract terms and conditions.

• Type of contract and payment schedule—sets forth the type of contract and the schedule of payments to be made during contract implementation.

The above SOW assumes a tightly controlled environment whereby the performing contractor has little latitude in deciding how to accomplish the activities. Each area is specified and the performing contractor provides the expertise and workmanship to complete the tasks.

6.6.3 Sample of a SOW

This sample provides an outline for preparing a specific SOW. There may be sections in this outline that need not be included in all project’s SOWs. Consideration should be given, however, to include in a SOW: an introduction and a brief background for the project under which this SOW will be issued; the scope of the effort, and specific objectives to be achieved; a list of the most significant reference items relevant to the project; requirements that define precisely what is needed in terms of tasks to be performed and deliverables to be produced; and progress and compliance to detail reporting requirements for the project. Additional areas that may be included are; transmittal/delivery/accessibility provisions, security requirements, or other requirements specific to your project. Attachments, if any, may be included.

• Introduction and overview. This statement of work will be issued under contract (name of contract and contract number). Briefly describe the project and its relationship to your mission.

• Background. Write a brief narrative describing how this project “came into being.”

• Scope of work. Begin with a narrative paragraph describing the scope of work covered by this SOW. When applicable, include an overall hierarchy of the work being performed; it can be in form of a work breakdown structure (WBS).

• Objectives. List the specific objectives for this SOW in bullet form. Be sure they are consistent with the scope and fit within the WBS, if provided.

• Period of performance. This section identifies the period of performance for the funding to be obligated under this action. If this action is for incremental funding, then the projected total period of performance to project completion, should also be included.

• Projected cost. If this action represents incremental or partial funding, list the total estimated cost for this task order, from this action to completion.

• References. All applicable documents referenced in this SOW are listed below. Where appropriate, a brief annotation should be provided to indicate the relevance of the document. Reference any specific requirements with regard to the use of these documents in performing the work under this SOW.

• Requirements. This section defines the requirements in terms of tasks to be performed, the end results/deliverables to be achieved, and the schedule of key dates. Important compliance requirements should be included with the task descriptions and deliverables.

• Tasks. The tasks to be performed under this contract shall be described in discrete functional areas, or subtasks, with each work area described clearly and completely. The Tasks description must provide sufficient detail that any contractor can understand the requirements, the methodology, and the outcomes and deliverables under the task.

• The contractor shall conduct the following tasks. List the tasks (number and name) in sequential order by phase (if applicable). Provide sufficient level of detail to enable the prospective contractor to plan personnel utilization and other requirements with maximum efficiency.

• Desired methodology

• Illustrations/drawings/diagrams, if any

• Specifications

• Data/property/facilities

• Level-of-effort

• Place/travel

• End results/deliverables. This section describes the products and tangible end results that are expected from each task contained in the previous section, the date each deliverable is due, and the buyer’s acceptance criteria.

• List of deliverables by task. For large efforts, deliverables may be divided by subtask. The following table provides a complete listing of the required deliverables by task. The table includes, task no. and name, end result/deliverable, tool for creating it, acceptance criteria, and intended use, as applicable.

• Schedules/milestones. The contractor shall maintain a detailed project schedule from which various project reports shall be produced. The following reports shall be provided:

• Who does what when report. The “who does what when” report shall be provided by the contractor with the initial submission, and again following negotiations. This report will be used by the buyer to assess the adequacy of the resources proposed by the contractor to accomplish the SOW.

• Other considerations. Include here any other relevant information for the performance of the SOW that does not fit elsewhere.

• Progress/compliance. The buyer requires the following from contractors in order to monitor progress and ensure compliance:

• Weekly status report

• Weekly meetings

• Monthly progress report

• Project management team (PMT) meetings

• Project reviews

• Outlines and drafts

• Transmittal/delivery/accessibility. The contractor shall provide two (2) hard copies of each paper deliverable and one electronic version.

• Notes. If for reasons of clarity or brevity previous sections need further amplification, use this section for that purpose and for all other information that does not logically fit into previous sections. The information designed to assist in determining the applicability of the specification and the selection of appropriate type, grade, or class of the product or service.

Note: This sample SOW has been adapted from a report format of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, D.C.

6.6.4 Other SOW Considerations

The SOW is often accompanied by a Specification that describes in detail the specific measures of the product being built by the project. Specifications compliment the SOW in that they detail the parameters of the product. Sometime, the specification items are included in the SOW.

In developing a SOW, one should consider the following items:

• What does the buyer want the performing contractor to do?

• How can one specify clearly the requirements?

• Are the requirements complete and understandable by all?

• Who does what in terms of the buyer and performing contractor?

• Does the SOW exercise enough control to give visibility into the work?

• Are the specified reports adequate to exercise control?

• Are the specified reviews adequate to exercise control?

• What criteria are used to measure the “goodness” of the product upon delivery?

6.6.5 Summary

A statement of work is simply the directions given to a performing contract by the buyer to ensure there is an understanding between the parties as to expectations of the buyer. The SOW should be clear and mutually agreed upon as to the meaning of its parts to accomplish the desired outcome. Furthermore, the SOW should be comprehensive in stating what, where, when, and how.

The SOW format is tailored to fit the needs of the buyer and a sample SOW may be a starting point from which one adds or subtracts items to ensure clear, unambiguous statements of the requirements. The SOW may also include specific parametric information that would normally be in a product specification.

6.7 SELECTING PM SOFTWARE

6.7.1 Introduction

Project management software programs have grown out of a need for better management of information in projects. Perhaps the first paper system was created by Henry L. Gantt in the early part of the twentieth century with the bar chart to schedule and control production efforts. This was not improved upon until the 1950s when the U.S. Navy and E.I. Dupont Company developed the program evaluation and review technique (PERT) and critical path method (CPM), respectively, as the foundation of modern schedule networks.

The advent of the computer and its growth since the 1980s has brought more and better software programs that meet the needs of project teams. Today, desktop computers with project management software give team members a powerful capability for planning and controlling projects. The software capabilities are dependent on the sophistication and complexity of the programs.

Project management software programs are available for projects with a variety of features. The cost of the programs range from $25 for the low end, basic scheduling tool to several thousands of dollars for the high end, mainframe hosted systems. The most popular programs, that is, those with the greatest sales volume, range in price from $300 to $600 for hosting on desktop computers.

Managing multiple projects or large projects that have many tasks and hundreds of resources requires the next step-up in project management software. Software that can accommodate projects or multiple projects with ease ranges in cost from approximately $2000 to $10,000. Selecting capable software will materially enhance the organization’s project management capability.

6.7.2 General Functions of Project Management Software

Project management software initially started with a scheduling function or the capability to layout tasks over time and track the progress of work. Later, the cost of project work was integrated into the software programs and most recently the resource management functions.

Project management software for the small to medium projects is currently designed to handle scheduling, resource management, and computed costs of resources. These general functions are addressed here, but not the more sophisticated functions, such as changing costs of resources over time.

Project management software generates critical decision-making information on time, cost, human resources, and material resources. |

Described below are the general functions that are the most common, and that provide the basics for all software programs. A short description is provided for each function:

• Time management—the capability to develop schedules that depict the work in tasks and summary activities. This is a planning requirement and then converts to a tracking function. Time management entails the capability to set a baseline and apply actual accomplishments into the schedule for measuring progress during the execution and closeout phases.

• Cost management—the capability to develop a project budget with detailed costs assigned to each task. The individual costs are summed to obtain the total anticipated cost of the project. Because costs are associated with each task and each task is placed in a time frame for execution, the budget is readily available as a time-phased plan for expenses. During execution and as resources are consumed, the system should be capable of accumulating expenditures for comparison against the baseline budget, both in detail and at the summary level.

• Human resource management—individuals with the requisite skills to accomplish project work on tasks are assigned to those tasks. This assignment makes the schedule a “resource-loaded” schedule with all identified people needed to complete the project. Because the resources are assigned to tasks, the time that they are required on the project is identified. The system should be capable of adding or changing the human resources during execution and closeout phases, as the situation dictates.

• Resources (other than human)—materials, equipment, vendor services, contracts, travel, rentals, and other costs may be required to complete the project. These resources can be assigned to tasks and the price of each entered into the schedule. This permits ordering and receipt of general resources for the project to meet the requirement in time for project continuation. The system should be capable of adding or changing the resources during execution and closeout phases, as the situation dictates.

These four categories are the minimum for software other than some low-end products that plan and track only schedule functions. These categories provide the capability to manage projects from extremely simple and of short durations to major projects with long durations.

6.7.3 Considerations for Software Selection