Chapter at a glance

Managerial work is interpersonal work, and the word "yes" can often open doors, particularly in situations prone to conflict or involving negotiations. Here's what to look for in Chapter 10. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

WHAT IS THE NATURE OF CONFLICT IN ORGANIZATIONS?

Types of Conflict

Levels of Conflict

Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict

Culture and Conflict

HOW CAN CONFLICT BE MANAGED?

Stages of Conflict

Causes of Conflict

Indirect Conflict Management Strategies

Direct Conflict Management Strategies

WHAT IS THE NATURE OF NEGOTIATION IN ORGANIZATIONS?

Negotiation Goals and Outcomes

Ethical Aspects of Negotiation

Organizational Settings for Negotiation

Culture and Negotiation

WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES FOR NEGOTIATION?

Distributive Negotiation

Integrative Negotiation

How to Gain Integrative Agreements

Common Negotiation Pitfalls

Third-Party Roles in Negotiation

Why is it that a CEO brought in from outside the industry fared the best as the big three automakers went into crisis mode during the economic downturn? That's a question that Ford Motor Company's chairman, William Clay Ford Jr., is happy to answer. The person he's talking about is Alan Mulally, a former Boeing executive hired to retool the automaker and put it back on a competitive track. Bill Ford says: "Alan was the right choice and it gets more right every day."

Many wondered at the time if an "airplane guy" could run an auto company. But Mulally's management experience and insights are proving well up to the task. One consultant remarked: "The speed with which Mulally has transformed Ford into a more nimble and healthy operation has been one of the more impressive jobs I've seen." He went on to say that without Mulally's impact Ford might well have gone out of business. One of his senior managers says: "I'm going into my fourth year on the job. I've never had such consistency of purpose before."

Alan Mulally makes mark by restructuring Ford.

In addition to many changes to modernize plants and streamline operations, Mulally tackled the problems dealing with functional chimneys and a lack of open communication. William Ford says that the firm had a culture that "loved to meet" and in which managers got together to discuss the message they wanted to communicate to the top executives: all agreement, no conflict. Mulally changed that with a focus on transparency, data-based decision making, and cooperation between divisions. When some of the senior executives balked and tried to complain to Ford, he refused to listen and reinforced Mulally's authority to run the firm his way. And when executives were reluctant to resolve conflicts among themselves, Mulally remained tough: "They can either work together or they can come see me," he says. And he hasn't shied away from the United Auto Workers Union either. He negotiated new agreements that brought labor costs down to be more competitive with arch-rival Toyota.

don't underestimate the power of "yes"

The daily work of organizations revolves around people and the interpersonal dynamics involved in getting them engaged in goal accomplishment. And just as in the case of Alan Mulally at Ford, we all need skills to work well with others who don't always agree with us and in team situations that are often complicated and stressful.[471] Conflict occurs whenever disagreements exist in a social situation over issues of substance, or whenever emotional antagonisms create frictions between individuals or groups.[472] Team leaders and members can spend considerable time dealing with conflicts; sometimes they are directly involved, and other times they act as mediators or neutral third parties to help resolve conflicts between other people.[473] Managers have to be comfortable with conflict dynamics in the workplace and know how to best deal with them. This includes being able to recognize situations that have the potential for conflict and address them in ways that will best serve the needs of both the organization and the people involved.[474]

Conflicts in teams, at work, and in our personal lives occur in at least two basic forms—substantive and emotional. Both types are common, ever present, and challenging. The question is: How well prepared are you to deal successfully with them?

Substantive conflict is a fundamental disagreement over ends or goals to be pursued and the means for their accomplishment.[475] A dispute with one's boss or other team members over a plan of action to be followed, such as the marketing strategy for a new product, is an example of substantive conflict. When people work together every day, it is only normal that different viewpoints on a variety of substantive workplace issues will arise. At times people will disagree over such things as team and organizational goals, the allocation of resources, the distribution of rewards, policies and procedures, and task assignments.

Substantive conflict involves fundamental disagreement over ends or goals to be pursued and the means for their accomplishment.

In contrast, emotional conflict involves interpersonal difficulties that arise over feelings of anger, mistrust, dislike, fear, resentment, and the like.[476] This conflict is commonly known as a "clash of personalities." How many times, for example, have you heard comments such as "I can't stand working with him" or "She always rubs me the wrong way" or "I wouldn't do what he asked if you begged me"? When emotional conflicts creep into work situations, they can drain energies and distract people from task priorities and goals. They can emerge in a wide variety of settings and are common in teams, among co-workers, and in superior-subordinate relationships.

Emotional conflict involves interpersonal difficulties that arise over feelings of anger, mistrust, dislike, fear, resentment, and the like.

Our first tendency may be to think of conflict as something that happens between people, and that is certainly a valid example of what we can call "interpersonal conflict." But scholars point out that conflicts in teams and organizations need to be recognized and understood on other levels as well. The full range of conflicts that we experience at work includes those emerging from the interpersonal, intrapersonal, intergroup, and interorganizational levels.

Interpersonal conflict occurs between two or more individuals who are in opposition to one another. It may be substantive, emotional, or both. Two persons debating each other aggressively on the merits of hiring a specific job applicant is an example of a substantive interpersonal conflict. Two persons continually in disagreement over each other's choice of work attire is an example of an emotional interpersonal conflict. Interpersonal conflict often arises in the performance evaluation process. When P. J. Smoot became learning and development leader at International Paper's Memphis, Tennessee, office, for example, she recognized that the traditional concept of the boss passing judgment often fails in motivating subordinates and improving their performance. So she started a new program that began the reviews from the bottom up—with the employee's self-evaluation and a focus on the manager's job as a coach and facilitator. Her advice is to "Listen for understanding and then react honestly and constructively. Focus on the business goals, not the personality."[477]

Interpersonal conflict occurs between two or more individuals in opposition to each other.

Intrapersonal conflict is tension experienced within the individual due to actual or perceived pressures from incompatible goals or expectations. Approach-approach conflict occurs when a person must choose between two positive and equally attractive alternatives. An example is when someone has to choose between a valued promotion in the organization or a desirable new job with another firm. Avoidance-avoidance conflict occurs when a person must choose between two negative and equally unattractive alternatives. An example is being asked either to accept a job transfer to another town in an undesirable location or to have one's employment with an organization terminated. Approach-avoidance conflict occurs when a person must decide to do something that has both positive and negative consequences. An example is being offered a higher-paying job with responsibilities that make unwanted demands on one's personal time.

Intrapersonal conflict occurs within the individual because of actual or perceived pressures from incompatible goals or expectations.

Intergroup conflict occurs between teams, perhaps ones competing for scarce resources or rewards, and perhaps ones whose members have emotional problems with one another. The classic example is conflict among functional groups or departments, such as marketing and manufacturing, within organizations. Sometimes such conflicts have substantive roots, such as marketing focusing on sales revenue goals and manufacturing focusing on cost efficiency goals. Other times such conflicts have emotional roots as "egos" in the respective departments cause each to want to look better than the other in a certain situation. Intergroup conflict is quite common in organizations, and it can make the coordination and integration of task activities very difficult.[478] The growing use of cross-functional teams and task forces is one way of trying to minimize such conflicts by improving horizontal communication.

Intergroup conflict occurs among groups in an organization.

Interorganizational conflict is most commonly thought of in terms of the competition and rivalry that characterizes firms operating in the same markets. A good example is the continuing battle between U.S. businesses and their global rivals: Ford vs. Toyota, or Nokia vs. Motorola, for example. But interorganizational conflict is a much broader issue than that represented by market competition alone. Other common examples include disagreements between unions and the organizations employing their members, between government regulatory agencies and the organizations subject to their surveillance, between organizations and their suppliers, and between organizations and outside activist groups.

Interorganizational conflict occurs between organizations.

There is no doubt that conflict in organizations can be upsetting both to the individuals directly involved and to others affected by its occurrence. It can be quite uncomfortable, for example, to work in an environment in which two co-workers are continually hostile toward each other or two teams are always battling for top management attention. In OB, and as shown in Figure 10.1, however, we recognize that conflict can have both a functional or constructive side and a dysfunctional or destructive side.

Functional conflict, also called constructive conflict, results in benefits to individuals, the team, or the organization. On the positive side, conflict can bring important problems to the surface so they can be addressed. It can cause decisions to be considered carefully and perhaps reconsidered to ensure that the right path of action is being followed. It can increase the amount of information used for decision making. And it can offer opportunities for creativity that can improve individual, team, or organizational performance. Indeed, an effective manager or team leader is able to stimulate constructive conflict in situations in which satisfaction with the status quo inhibits needed change and development.

Functional conflict results in positive benefits to the group.

Dysfunctional conflict, or destructive conflict, works to the disadvantage of an individual or team. It diverts energies, hurts group cohesion, promotes interpersonal hostilities, and overall creates a negative environment for workers. This type of conflict occurs, for example, when two team members are unable to work together because of interpersonal differences—a destructive emotional conflict, or when the members of a work unit fail to act because they cannot agree on task goals—a destructive substantive conflict. Destructive conflicts of these types can decrease performance and job satisfaction as well as contribute to absenteeism and job turnover. Managers and team leaders should be alert to destructive conflicts and be quick to take action to prevent or eliminate them—or at least minimize their disadvantages.

Dysfunctional conflict works to the group's or organization's disadvantage.

Society today shows many signs of wear and tear in social relationships. We experience difficulties born of racial tensions, homophobia, gender gaps, and more. All trace their roots to tensions among people who are different from one another in some way. They are also a reminder that culture and cultural differences must be considered for their conflict potential. Among the dimensions of national culture, for example, substantial differences may be noted in time orientation. When persons from short-term cultures such as the United States try to work with persons from long-term cultures such as Japan, the likelihood of conflict developing is high. The same holds true when individualists work with collectivists and when persons from high-power-distance cultures work with those from low-power-distance cultures.[479]

People who are not able or willing to recognize and respect cultural differences can contribute to the emergence of dysfunctional situations in multicultural teams. On the other hand, sensitivity and respect when working across cultures can often tap the performance advantages of both diversity and constructive conflict. Consider these comments from members of a joint European and American project team at Corning. "Something magical happens," says engineer John Thomas. "Europeans are very creative thinkers; they take time to really reflect on a problem to come up with the very best theoretical solution, Americans are more tactical and practical—we want to get down to developing a working solution as soon as possible." His partner at Fontainebleau in France says: "The French are more focused on ideas and concepts. If we get blocked in the execution of those ideas, we give up. Not the Americans. They pay more attention to details, processes, and time schedules. They make sure they are prepared and have involved everyone in the planning process so that they won't get blocked. But it's best if you mix the two approaches. In the end, you will achieve the best results."[480]

Conflict can be addressed in many ways, but the important goal is to achieve or set the stage for true conflict resolution—a situation in which the underlying reasons for dysfunctional conflict are eliminated. When conflicts go unresolved the stage is often set for future conflicts of the same or related sort. Rather than trying to deny the existence of conflict or settle on a temporary resolution, it is always best to deal with important conflicts in such ways that they are completely re-solved.[481] This requires a good understanding of the stages of conflict, the potential causes of conflict, and indirect and direct approaches to conflict management.

Conflict resolution occurs when the reasons for a conflict are eliminated.

Most conflicts develop in stages, as shown in Figure 10.2. Conflict antecedents establish the conditions from which conflicts are likely to develop. When the antecedent conditions become the basis for substantive or emotional differences between people or groups, the stage of perceived conflict exists. Of course, this perception may be held by only one of the conflicting parties. It is important to distinguish between perceived and felt conflict. When conflict is felt, it is experienced as tension that motivates the person to take action to reduce feelings of discomfort. For conflict to be resolved, all parties should perceive the conflict and feel the need to do something about it.

Manifest conflict is expressed openly in behavior. It is followed by conflict aftermath. At this stage removing or correcting the antecedents results in conflict resolution while failing to do so results in conflict suppression. With suppression, no change in antecedent conditions occurs even though the manifest conflict behaviors may be temporarily controlled. This occurs, for example, when one or both parties choose to ignore conflict in their dealings with one another. Conflict suppression is a superficial and often temporary state that leaves the situation open to future conflicts over similar issues. Although it is perhaps useful in the short run, only true conflict resolution establishes conditions that eliminate an existing conflict and reduce the potential for it to recur in the future.

The very nature of organizations as hierarchical systems provides a basis for conflict as individuals and teams work within the authority structure. Vertical conflict occurs between levels and commonly involves supervisor-subordinate and team leader-team member disagreements over resources, goals, deadlines, or performance results. Horizontal conflict occurs between persons or groups working at the same hierarchical level. These disputes commonly involve goal incompatibilities, resource scarcities, or purely interpersonal factors. And, line-staff conflict involves disagreements between line and staff personnel over who has authority and control over decisions on matters such as budgets, technology, and human resource practices. Also common are role ambiguity conflicts that occur when the communication of task expectations is unclear or upsetting in some way, such as a team member receiving different expectations from different sources. Conflict is likely when individuals or teams are placed in ambiguous situations where it is difficult for them to understand just who is responsible for what, and why.

Task and workflow interdependencies are breeding grounds for conflicts. Disputes and open disagreements may erupt among people and teams that are required to cooperate to meet challenging goals.[482] When interdependence is high—that is, when a person or group must rely on or ask for contributions from one or more others to achieve its goals—conflicts often occur. You will notice this, for example, in a fast-food restaurant, when the people serving the food have to wait too long for it to be delivered from the cooks. Conflict escalates with structural differentiation where different teams and work units pursue different goals with different time horizons as shown in Figure 10.3. Conflict also develops out of domain ambiguities when individuals or teams lack adequate task direction or goals and misunderstand such things as customer jurisdiction or scope of authority.

Actual or perceived resource scarcity can foster destructive competition. When resources are scarce, working relationships are likely to suffer. This is especially true in organizations that are experiencing downsizing or financial difficulties. As cutbacks occur, various individuals or teams try to position themselves to gain or retain maximum shares of the shrinking resource pool. They are also likely to resist resource redistribution or to employ countermeasures to defend their resources from redistribution to others.

Also, power or value asymmetries in work relationships can create conflict. They exist when interdependent people or teams differ substantially from one another in status and influence or in values. Conflict resulting from asymmetry is prone to occur, for example, when a low-power person needs the help of a high-power person who does not respond, when people who hold dramatically different values are forced to work together on a task, or when a high-status person is required to interact with and perhaps be dependent on someone of lower status.

Most managers will tell you that not all conflict management in teams and organizations can be resolved by getting the people involved to adopt new attitudes, behaviors, and stances toward one another. Think about it. Aren't there likely to be times when personalities and emotions prove irreconcilable? In such cases a more indirect or structural approach to conflict management can often help. It uses such strategies as reduced interdependence, appeals to common goals, hierarchical referral, and alterations in the use of mythology and scripts to deal with the conflict situation.

Reduced Interdependence When workflow conflicts exist, managers can adjust the level of interdependency among teams or individuals.[483] One simple option is decoupling, or taking action to eliminate or reduce the required contact between conflicting parties. In some cases team tasks can be adjusted to reduce the number of required points of coordination. The conflicting units can then be separated from one another, and each can be provided separate access to valued resources. Although decoupling may reduce conflict, it may also result in duplication and a poor allocation of valued resources.

Buffering is another approach that can be used when the inputs of one team are the outputs of another. The classic buffering technique is to build an inventory, or buffer, between the teams so that any output slowdown or excess is absorbed by the inventory and does not directly pressure the target group. Although it reduces conflict, this technique is increasingly out of favor because it increases inventory costs. This consequence is contrary to the elements of just-in-time delivery, which is now valued in operations management.

Conflict management can sometimes be facilitated by assigning people to serve as formal linking pins between groups that are prone to conflict.[484] Persons in linking-pin roles, such as project liaisons, are expected to understand the operations, members, needs, and norms of their host teams. They are supposed to use this knowledge to help the team work better with others in order to accomplish mutual tasks. Although expensive, this technique is often used when different specialized groups, such as engineering and sales, must closely coordinate their efforts on complex and long-term projects.

Appeals to Common Goals An appeal to common goals can focus the attention of potentially conflicting individuals and teams on one mutually desirable conclusion. By elevating the potential dispute to a common framework wherein the parties recognize their mutual interdependence in achieving common goals, petty disputes can be put in perspective. In a course team where members are arguing over content choices for a PowerPoint presentation, for example, it might help to remind everyone that the goal is to impress the instructor and get an "A" for the presentation and that this is only possible if everyone contributes their best. An appeal to higher goals offers a common frame of reference that can be very helpful for analyzing differences and reconciling disagreements.

Hierarchical Referral Hierarchical referral uses the chain of command for conflict resolution.[485] Here, problems are moved from the level of conflicting individuals or teams and referred up the hierarchy for more senior managers to address. Whereas hierarchical referral can be definitive in a given case, it also has limitations. If conflict is severe and recurring, the continual use of hierarchical referral may not result in true conflict resolution. Managers removed from day-to-day affairs may fail to diagnose the real causes of a conflict, and conflict resolution may be superficial. Busy managers may tend to consider most conflicts as results of poor interpersonal relations and may act quickly to replace a person with a perceived "personality" problem.

Altering Scripts and Myths In some situations, conflict is superficially managed by scripts, or behavioral routines, that become part of the organization's culture.[486] The scripts become rituals that allow the conflicting parties to vent their frustrations and to recognize that they are mutually dependent on one another via the larger corporation. An example is a monthly meeting of "department heads," which is held presumably for purposes of coordination and problem solving but actually becomes just a polite forum for superficial agreement.[487] Managers in such cases know their scripts and accept the difficulty of truly resolving any major conflicts. By sticking with the script, expressing only low-key disagreement, and then quickly acting as if everything has been resolved, for instance, the managers publicly act as if problems are being addressed. Such scripts can be altered to allow and encourage active confrontation of issues and disagreements.

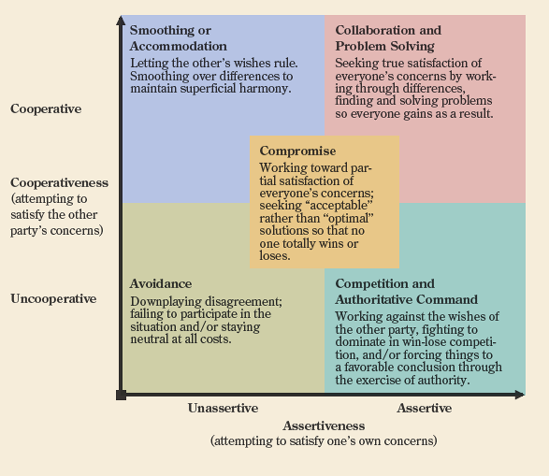

In addition to the indirect conflict management strategies just discussed, it is also very important for everyone to understand how conflict management plays out in face-to-face fashion. Figure 10.4 shows five direct conflict management strategies that vary in their emphasis on cooperativeness and assertiveness in the interpersonal dynamics of the situation. Consultants and academics generally agree that true conflict resolution can occur only when the underlying substantive and emotional reasons for the conflict are identified and dealt with through a solution that allows all conflicting parties to "win." However, the reality is that direct conflict management may pursue lose-lose and win-lose as well as win-win outcomes.[488]

Lose-Lose Strategies Lose-lose conflict occurs when nobody really gets what he or she wants in a conflict situation. The underlying reasons for the conflict remain unaffected, and a similar conflict is likely to occur in the future. Lose-lose outcomes are likely when the conflict management strategies involve little or no assertiveness.

Avoidance is an extreme form that basically displays no attention toward a conflict. No one acts assertively or cooperatively; everyone simply pretends the conflict does not really exist and hopes it will go away. Accommodation, or smoothing as it is sometimes called, involves playing down differences among the conflicting parties and highlighting similarities and areas of agreement. This peaceful coexistence ignores the real essence of a given conflict and often creates frustration and resentment. Compromise occurs when each party shows moderate assertiveness and cooperation and is ultimately willing to give up something of value to the other. As a result of no one getting their full desires, the antecedent conditions for future conflicts are established. See OB Savvy 15.1 for tips on when to use this and other conflict management styles.

Avoidance involves pretending a conflict does not really exist.

Accommodation, or smoothing, involves playing down differences and finding areas of agreement.

Compromise occurs when each party gives up something of value to the other.

Win-Lose Strategies In win-lose conflict, one party achieves its desires at the expense and to the exclusion of the other party's desires. This is a high-assertiveness and low-cooperativeness situation. It may result from outright competition in which one party achieves a victory through force, superior skill, or domination. It may also occur as a result of authoritative command, whereby a formal authority such as manager or team leader simply dictates a solution and specifies what is gained and what is lost by whom. Win-lose strategies of these types fail to address the root causes of the conflict and tend to suppress the desires of at least one of the conflicting parties. As a result, future conflicts over the same issues are likely to occur.

Win-Win Strategies Win-win conflict is achieved by a blend of both high cooperativeness and high assertiveness.[489] Collaboration, or problem solving, involves recognition by all conflicting parties that something is wrong and needs attention. It stresses gathering and evaluating information in solving disputes and making choices. Win-win outcomes eliminate the reasons for continuing or resurrecting the conflict because nothing has been avoided or suppressed. All relevant issues are raised and openly discussed.

Collaboration involves recognition that something is wrong and needs attention through problem solving.

The ultimate test for collaboration and a win-win solution is whether or not the conflicting parties see that the solution to the conflict (1) achieves each party's goals, (2) is acceptable to both parties, and (3) establishes a process whereby all parties involved see a responsibility to be open and honest about facts and feelings. When success in each of these areas is achieved, the likelihood of true conflict resolution is greatly increased. However, it is also important to recognize that collaboration and problem solving often take time and consume lots of energy; something to which the parties must be willing to commit. Collaboration and problem solving may not be feasible if the firm's dominant culture rewards competition too highly and fails to place a value on cooperation.[490] And finally, OB Savvy 10.2 points out that each of the conflict management strategies has advantages under certain conditions.

Picture yourself trying to make a decision in the following situation: You are about to order a new state-of-the-art notebook computer for a team member in your department. Then another team member submits a request for one of a different brand. Your boss says that only one brand can be ordered. Or consider this one: You have been offered a new job in another city and want to take it, but are disappointed with the salary. You've heard friends talk of how they "negotiated" better offers when taking jobs. You are concerned about the costs of relocating and would like a signing bonus as well as a guarantee of an early salary review.

The preceding examples are just two of the many situations that involve negotiation—the process of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences.[491] Negotiation has special significance in teams and work settings, where disagreements are likely to arise over such diverse matters as wage rates, task objectives, performance evaluations, job assignments, work schedules, work locations, and more.

Negotiation is the process of making joint decisions when the parties involved have different preferences.

Two important goals must be considered in any negotiation: substance goals and relationship goals. Substance goals deal with outcomes that relate to the "content" issues under negotiation. The dollar amount of a wage agreement in a collective-bargaining situation is one example. Relationship goals deal with outcomes that relate to how well people involved in the negotiation and any constituencies they may represent are able to work with one another once the process is concluded. An example is the ability of union members and management representatives to work together effectively after a contract dispute has been settled.

Unfortunately, many negotiations result in damaged relationships because the negotiating parties become preoccupied with substance goals and self-interests. In contrast, effective negotiation occurs when substance issues are resolved and working relationships are maintained or even improved. Three criteria for effective negotiation are:

Effective negotiation occurs when substance issues are resolved and working relationships are maintained or improved.

Quality—The negotiation results offer a "quality" agreement that is wise and satisfactory to all sides.

Harmony—The negotiation is "harmonious" and fosters rather than inhibits good interpersonal relations.

Efficiency—The negotiation is "efficient" and no more time consuming or costly than absolutely necessary.

Managers and others involved in negotiations should strive for high ethical standards of conduct, but this goal can get sidetracked by an overemphasis on self-interests. The motivation to behave ethically in negotiations is put to the test by each party's desire to "get more" than the other from the negotiation and/or by a belief that there are insufficient resources to satisfy all parties.[492] After the heat of negotiations dies down, the parties involved often try to rationalize or explain away questionable ethics as unavoidable, harmless, or justified. Such after-the-fact rationalizations may be offset by long-run negative consequences, such as not being able to achieve one's wishes again the next time. At the very least the unethical party may be the target of revenge tactics by those who were disadvantaged. Furthermore, once some people have behaved unethically in one situation, they may become entrapped by such behavior and prone to display it again in the future.[493]

Managers and team leaders should be prepared to participate in at least four major action settings for negotiations. In two-party negotiation the manager negotiates directly with one other person. In a group negotiation the manager is part of a team or group whose members are negotiating to arrive at a common decision. In an intergroup negotiation the manager is part of a group that is negotiating with another group to arrive at a decision regarding a problem or situation affecting both. And in a constituency negotiation each party represents a broader constituency, for example, representatives of management and labor negotiating a collective bargaining agreement.

The existence of cultural differences in time orientation, individualism, collectivism, and power distance can have a substantial impact on negotiation. For example, when American business executives try to negotiate quickly with their Chinese counterparts, culture is not always on their side. A typical Chinese approach to negotiation might move much more slowly, require the development of good interpersonal relationships prior to reaching any agreement, display reluctance to commit everything to writing, and anticipate that any agreement reached will be subject to modification as future circumstances may require.[494] All this is quite the opposite of the typical expectations of negotiators used to the individualist and short-term American culture.

When we think about negotiating for something, perhaps cars and salaries are the first things that pop into mind. But in organizations, managers and workers alike are constantly negotiating over not only just pay and raises, but also such things as work goals or preferences and access to any variety of scarce resources. These resources may be money, time, people, facilities, equipment, and so on. In all such cases the general approach to, or strategy for, the negotiation can have a major influence on its outcomes. In OB we generally talk about two broad approaches—distributive and integrative.

In distributive negotiation the focus is on "positions" staked out or declared by conflicting parties. Each party is trying to claim certain portions of the available "pie" whose overall size is considered fixed. In integrative negotiation, sometimes called principled negotiation, the focus is on the "merits" of the issues. Everyone involved tries to enlarge the available pie and find mutually agreed-upon ways of distributing it, rather than stake claims to certain portions of it.[495] Think of the conversations you overhear and are part of in team situations. The notion of "my way or the highway" is analogous to distribution negotiation; "let's find a way to make this work for both of us" is more akin to integrative negotiation.

Distributive negotiation focuses on positions staked out or declared by the parties involved, each of whom is trying to claim certain portions of the available pie.

Integrative negotiation focuses on the merits of the issues, and the parties involved try to enlarge the available pie rather than stake claims to certain portions of it.

In distributive bargaining approaches, the participants would each ask this question: "Who is going to get this resource?" This question frames the negotiation as a "win-lose" episode that will have a major impact on how parties approach the negotiation process and the outcomes that may be achieved. A case of distributive negotiation usually unfolds in one of two directions, with neither one nor the other yielding optimal results.

"Hard" distributive negotiation takes place when each party holds out to get its own way. This leads to competition, whereby each party seeks dominance over the other and tries to maximize self-interests. The hard approach may lead to a win-lose outcome in which one party dominates and gains. Or it can lead to an impasse.

"Soft" distributive negotiation, in contrast, takes place when one party is willing to make concessions to the other to get things over with. In this case one party tries to find ways to meet the other's desires. A soft approach leads to accommodation, in which one party gives in to the other, or to compromise, in which each party gives up something of value in order to reach agreement. In either case at least some latent dissatisfaction is likely to develop. Even when the soft approach results in compromise (e.g., splitting the difference between the initial positions equally), dissatisfaction may exist since each party is still deprived of what it originally wanted.

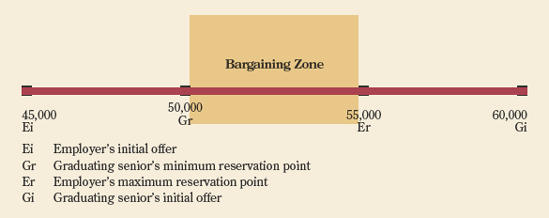

Figure 10.5 illustrates the basic elements of classic two-party negotiation by the example of the graduating senior negotiating a job offer with a corporate recruiter.[496] Look at the situation first from the graduate's perspective. She has told the recruiter that she would like a salary of $55,000; this is her initial offer. But she also has in mind a minimum reservation point of $50,000—the lowest salary that she will accept for this job. Thus she communicates a salary request of $55,000 but is willing to accept one as low as $50,000. The situation is somewhat the reverse from the recruiter's perspective. His initial offer to the graduate is $45,000, and his maximum reservation point is $55,000; this is the most he is prepared to pay.

The bargaining zone is defined as the range between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum reservation point. In Figure 10.5, the bargaining zone is $50,000-$55,000. This is a positive bargaining zone since the reservation points of the two parties overlap. Whenever a positive bargaining zone exists, bargaining has room to unfold. Had the graduate's minimum reservation point been greater than the recruiter's maximum reservation point (for example, $57,000), no room would have existed for bargaining. Classic two-party bargaining always involves the delicate tasks of first discovering the respective reservation points (one's own and the other's), and then working toward an agreement that lies somewhere within the resulting bargaining zone and is acceptable to each party.

The bargaining zone is the range between one party's minimum reservation point and the other party's maximum.

In the integrative approach to negotiation, participants begin by asking not "Who's going to get this resource?" but "How can the resource best be used?" The latter question is much less confrontational than the former, and it permits a broader range of alternatives to be considered in the negotiation process. From the outset there is much more of a "win-win" orientation.

At one extreme, integrative negotiation may involve selective avoidance, in which both parties realize that there are more important things on which to focus their time and attention. The time, energy, and effort needed to negotiate may not be worth the rewards. Compromise can also play a role in the integrative approach, but it must have an enduring basis. This is most likely to occur when the compromise involves each party giving up something of perceived lesser personal value to gain something of greater value. For instance, in the classic two-party bargaining case over salary, both the graduate and the recruiter could expand the negotiation to include the starting date of the job. Because it will be a year before the candidate's first vacation, she may be willing to take a little less money if she can start a few weeks later. Finally, integrative negotiation may involve true collaboration. In this case, the negotiating parties engage in problem solving to arrive at a mutual agreement that maximizes benefits to each.

Underlying the integrative or principled approach is a willingness to negotiate based on the merits of the situation. The foundations for gaining truly integrative agreements can be described as supportive attitudes, constructive behaviors, and good information.[497]

Attitudinal Foundations There are three attitudinal foundations of integrative agreements. First, each party must approach the negotiation with a willingness to trust the other party. This is a reason why ethics and maintaining relationships are so important in negotiations. Second, each party must convey a willingness to share information with the other party. Without shared information, effective problem solving is unlikely to occur. Third, each party must show a willingness to ask concrete questions of the other party. This further facilitates information sharing.

Behavioral Foundations During a negotiation all behavior is important for both its actual impact and the impressions it leaves behind. Accordingly, the following behavioral foundations of integrative agreements must be carefully considered and included in any negotiator's repertoire of skills and capabilities:

Separate people from the problem.

Don't allow emotional considerations to affect the negotiation.

Focus on interests rather than positions.

Avoid premature judgments.

Keep the identification of alternatives separate from their evaluation.

Judge possible agreements by set criteria or standards.

Information Foundations The information foundations of integrative agreements are substantial. They involve each party becoming familiar with the BATNA, or "best alternative to a negotiated agreement." That is, each party must know what he or she will do if an agreement cannot be reached. This requires that both negotiating parties identify and understand their personal interests in the situation. They must know what is really important to them in the case at hand, and they must come to understand the relative importance of the other party's interests. As difficult as it may seem, each party must achieve an understanding of what the other party values, even to the point of determining its BATNA.

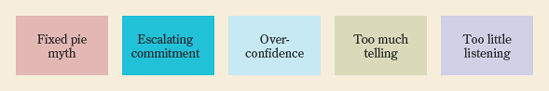

The negotiation process is admittedly complex on ethical, cultural, and many other grounds. It is further characterized by all the possible confusions of complex, and sometimes even volatile interpersonal and team dynamics. Accordingly, negotiators need to guard against some common negotiation pitfalls when acting individually and in teams.[498]

The first pitfall is the tendency in negotiation to stake out your position based on the assumption that in order to gain your way, something must be subtracted from the gains of the other party. This myth of the fixed pie is a purely distributive approach to negotiation. The whole concept of integrative negotiation is based on the premise that the pie can sometimes be expanded or used to the maximum advantage of all parties, not just one.

Second, because parties to negotiations often begin by stating extreme demands, the possibility of escalating commitment is high. That is, once demands have been stated, people become committed to them and are reluctant to back down. Concerns for protecting one's ego and saving face may lead to the irrational escalation of a conflict. Self-discipline is needed to spot this tendency in one's own behavior as well as in the behavior of others.

Third, negotiators often develop overconfidence that their positions are the only correct ones. This can lead them to ignore the other party's needs. In some cases negotiators completely fail to see merits in the other party's position—merits that an outside observer would be sure to spot. Such overconfidence makes it harder to reach a positive common agreement.

Fourth, communication problems can cause difficulties during a negotiation. It has been said that "negotiation is the process of communicating back and forth for the purpose of reaching a joint decision."[499] This process can break down because of a telling problem—the parties don't really talk to each other, at least not in the sense of making themselves truly understood. It can also be damaged by a hearing problem—the parties are unable or unwilling to listen well enough to understand what the other is saying. Indeed, positive negotiation is most likely when each party engages in active listening and frequently asks questions to clarify what the other is saying. Each party occasionally needs to "stand in the other party's shoes" and to view the situation from the other's perspective.[500]

Negotiation may sometimes be accomplished through the intervention of third parties, such as when stalemates occur and matters appear not resolvable under current circumstances. In a process called alternative dispute resolution, a neutral third party works with persons involved in a negotiation to help them resolve impasses and settle disputes. There are two primary forms through which ADR is implemented.

In arbitration, such as the salary arbitration now common in professional sports, the neutral third party acts as a "judge" and has the power to issue a decision that is binding on all parties. This ruling takes place after the arbitrator listens to the positions advanced by the parties involved in a dispute. In mediation, the neutral third party tries to engage the parties in a negotiated solution through persuasion and rational argument. This is a common approach in labor-management negotiations, where trained mediators acceptable to both sides are called in to help resolve bargaining impasses. Unlike an arbitrator, the mediator is not able to dictate a solution.

In arbitration a neutral third party acts as judge with the power to issue a decision binding for all parties.

In mediation a neutral third party tries to engage the parties in a negotiated solution through persuasion and rational argument.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 10.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 10 study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

What is the nature of conflict in organizations?

Conflict appears as a disagreement over issues of substance or emotional antagonisms that create friction between individuals or teams.

Conflict situations in organizations occur at intrapersonal, interpersonal, intergroup, and interorganizational levels.

When kept within tolerable limits, conflict can be a source of creativity and performance enhancement; it becomes destructive when these limits are exceeded.

Moderate levels of conflict can be functional for performance, stimulating effort and creativity.

Too little conflict is dysfunctional when it leads to complacency; too much conflict is dysfunctional when it overwhelms us.

How can conflict be managed?

Most typically, conflict develops through a series of stages, beginning with antecedent conditions and progressing into manifest conflict.

Unresolved prior conflicts set the stage for future conflicts of a similar nature.

Indirect conflict management strategies include appeals to common goals, hierarchical referral, organizational redesign, and the use of mythology and scripts.

Direct conflict management strategies engage different tendencies toward cooperativeness and assertiveness to styles of avoidance, accommodation, compromise, competition, and collaboration.

Win-win conflict is achieved through collaboration and problem solving.

Win-lose conflict is associated with competition and authoritative command.

Lose-lose conflict results from avoidance, smoothing or accommodation, and compromise.

What is the nature of negotiation in organizations?

Negotiation is the process of making decisions and reaching agreement in situations in which the participants have different preferences.

Managers may find themselves involved in various types of negotiation situations, including two-party, group, intergroup, and constituency negotiation.

Effective negotiation occurs when both substance goals (dealing with outcomes) and relationship goals (dealing with processes) are achieved.

Ethical problems in negotiation can arise when people become manipulative and dishonest in trying to satisfy their self-interests at any cost.

What are the different strategies for negotiation?

The distributive approach to negotiation emphasizes win-lose outcomes; the integrative or principled approach to negotiation emphasizes win-win outcomes.

In distributive negotiation the focus of each party is on staking out positions in the attempt to claim desired portions of a "fixed pie."

In integrative negotiation, sometimes called principled negotiation, the focus is on determining the merits of the issues and finding ways to satisfy one another's needs.

The success of negotiations often depends on avoiding common pitfalls such as the myth of the fixed pie, escalating commitment, overconfidence, and both the telling and hearing problems.

When negotiations are at an impasse, third-party approaches such as mediation and arbitration offer alternative and structured ways for dispute resolution.

Accommodation (smoothing) (p. 241)

Arbitration (p. 249)

Authoritative command (p. 241)

Avoidance (p. 241)

Bargaining zone (p. 246)

Collaboration (p. 241)

Competition (p. 241)

Compromise (p. 241)

Conflict (p. 232)

Conflict resolution (p. 236)

Distributive negotiation (p. 244)

Dysfunctional conflict (p. 234)

Effective negotiation (p. 242)

Emotional conflict (p. 232)

Functional conflict (p. 234)

Integrative negotiation (p. 244)

Intergroup conflict (p. 233)

Interorganizational conflict (p. 233)

Interpersonal conflict (p. 233)

Intrapersonal conflict (p. 233)

Mediation (p. 249)

Negotiation (p. 242)

Substantive conflict (p. 232)

A/an ____________ conflict occurs in the form of a fundamental disagreement over ends or goals and the means for accomplishment. (a) relationship (b) emotional (c) substantive (d) procedural

The indirect conflict management approach that uses chain of command for conflict resolution is known as ____________. (a) hierarchical referral (b) avoidance (c) smoothing (d) appeal to common goals

Conflict that ends up being "functional" for the people and organization involved would most likely be ____________. (a) of high intensity (b) of moderate intensity (c) of low intensity (d) nonexistent

One of the problems with the suppression of conflicts is that it ____________. (a) creates winners and losers (b) is often a temporary solution that sets the stage for future conflict (c) works only with emotional conflicts (d) works only with substantive conflicts

When a manager asks people in conflict to remember the mission and purpose of the organization and to try to reconcile their differences in that context, she is using a conflict management approach known as ____________. (a) reduced interdependence (b) buffering (c) resource expansion (d) appeal to common goals

The best time to use accommodation in conflict management is ____________. (a) when quick and decisive action is vital (b) when you want to build "credit" for use in later disagreements (c) when people need to cool down and gain perspective (d) when temporary settlement of complex issues is needed

Which is an indirect approach to managing conflict? (a) buffering (b) win-lose (c) workflow interdependency (d) power asymmetry

A lose-lose conflict is likely when the conflict management approach focuses on ____________. (a) linking pin roles (b) altering scripts (c) accommodation (d) problem-solving

Which approach to conflict management can be best described as both highly cooperative and highly assertive? (a) competition (b) compromise (c) accommodation (d) collaboration

Both ____________ goals should be considered in any negotiation. (a) performance and evaluation (b) task and substance (c) substance and relationship (d) task and performance

The three criteria for effective negotiation are ____________. (a) harmony, efficiency, and quality (b) quality, efficiency, and effectiveness (c) ethical behavior, practicality, and cost-effectiveness (d) quality, practicality, and productivity

Which statement is true? (a) Principled negotiation leads to accommodation. (b) Hard distributive negotiation leads to collaboration. (c) Soft distributive negotiation leads to accommodation or compromise. (d) Hard distributive negotiation leads to win-win conflicts.

Another name for integrative negotiation is ____________. (a) arbitration (b) mediation (c) principled negotiation (d) smoothing

When a person approaches a negotiation with the assumption that in order for him to gain his way, the other party must lose or give up something, which negotiation pitfall is being exhibited? (a) myth of the fixed pie (b) escalating commitment (c) overconfidence (d) hearing problem

In the process of alternative dispute resolution known as ____________, a neutral third party acts as a "judge" to determine how a conflict will be resolved. (a) mediation (b) arbitration (c) conciliation (d) collaboration

List and discuss three conflict situations faced by managers.

List and discuss the major indirect conflict management approaches.

Under what conditions might a manager use avoidance or accommodation?

Compare and contrast distributive and integrative negotiation. Which is more desirable? Why?