Chapter at a glance

To get the best teamwork you have to build teams with strong team processes. Here's what to look for in Chapter 8. Don't forget to check your learning with the Summary Questions & Answers and Self-Test in the end-of-chapter Study Guide.

HOW CAN WE CREATE HIGH-PERFORMANCE TEAMS?

Characteristics of High-Performance Teams

The Team-Building Process

Team-Building Alternatives

HOW CAN TEAM PROCESSES BE IMPROVED?

Entry of New Members

Task and Maintenance Leadership

Roles and Role Dynamics

Team Norms

Team Cohesiveness

Inter-Team Dynamics

HOW CAN TEAM COMMUNICATIONS BE IMPROVED?

Communication Networks

Proxemics and Use of Space

Communication Technologies

HOW CAN TEAM DECISIONS BE IMPROVED?

Ways Teams Make Decisions

Assets and Liabilities of Team Decisions

Groupthink Symptoms and Remedies

Team Decision Techniques

Have you had your dose of reality TV this week? It's turned into quite the phenomenon, but not just one for the living room voyeur. Welcome to the new world of "reality" team-building.

Chances are that while you have probably tuned in to one of the many TV reality shows, you couldn't imagine actually being on one. But get ready, your next corporate training stop may be reality-based. It seems some organizations are finding the "reality" notion is a great way to accomplish team-building and drive innovation.

"There's something magical about taking smart people out of their safety zones and making them spend night and day together."

Best Buy sent teams of salespeople, all strangers at the start, to live together for 10 weeks in Los Angeles apartments. The purpose was to engage one another and come up with new ideas for the firm. One of the ideas was for Best Buy Studio, a new venture serving small businesses with Web design services and consulting. Jeremy Sevush came up with the idea, and with support from his team, he was able to implement it shortly after moving out of the apartment. He says: "Living together and knowing we only had 10 weeks sped up our team-building process."

John Wopert runs the program for Best Buy from his consulting firm Team upStart. He claims: "There's something magical about taking smart people out of their safety zones and making them spend night and day together."

Some call the reality team-building experiences "extreme brainstorming," and it seems to fit today's generation of workers. In a program called Real Whirled, small teams from Whirlpool live together for seven weeks while using the company's appliances. IBM has a program called Extreme Blue to incubate new business ideas.

teams are hard work but they can be worth it

Are you an iPod, iPhone, iTouch, or iMac user? Have you ever wondered who and what launched Apple, Inc. on the pathway to giving us a stream of innovative and trendsetting products? We might say that the story started with Apple's co-founder Steve Jobs, the first Macintosh computer, and a very special team. The "Mac" was Jobs's brainchild; and to create it he put together a team of high-achievers who were excited and turned on to a highly challenging task. They worked all hours and at an unrelenting pace, while housed in a separate building flying the Jolly Roger. To display their independence from Apple's normal bureaucracy, the MacIntosh team combined youthful enthusiasm with great expertise and commitment to an exciting goal. In the process they set a new benchmark for product innovation as well as new standards for what makes for a high-performance team.[394]

The Apple story and the opening vignette on reality team-building are interesting examples of how teams and teamwork can be harnessed to stimulate innovations. But let's not forget that there are a lot of solid contributions made by good, old-fashioned, everyday teams in organizations as well—the cross-functional, problem-solving, virtual, and self-managing teams introduced in the last chapter. We also need to remember, as scholar J. Richard Hackman points out, that many teams underperform and fail to live up to their potential; they simply, as Hackman says, "don't work."[395] The question becomes: What differentiates high performing teams from the also-rans?

Some "must have" team leadership skills are described in OB Savvy 8.1. And it's appropriate that "setting a clear and challenging direction" is at the top of the list.[396] Whatever the purpose or tasks, the foundation for any high performing team is a set of members who believe in team goals and are motivated to work hard to accomplish them. Indeed, an essential criterion of a high-performance team is that the members feel "collectively accountable" for moving together in what Hackman calls "a compelling direction" toward a goal. Yet, he points out that in "most" teams, members don't agree on the goal and don't share an understanding of what the team is supposed to accomplish.[397]

High-performance teams also are able to turn a general sense of purpose into specific performance objectives. Whereas a shared sense of purpose gives general direction to a team, commitment to targeted performance results makes this purpose truly meaningful. Specific objectives provide a clear focus for solving problems and resolving conflicts. They also set standards for measuring results and obtaining performance feedback. And they help group members understand the need for collective versus purely individual efforts. Again, the Macintosh story sets an example. In November, 1983, Wired magazine's correspondent Steven Levy was given a sneak look at what he had been told was the "machine that was supposed to change the world." He says: "I also met the people who created that machine. They were groggy and almost giddy from three years of creation. Their eyes blazed with Visine and fire. They told me that with Macintosh, they were going to "put a dent in the Universe." Their leader, Steven P. Jobs, told them so. They also told me how Jobs referred to this new computer: 'Insanely Great.'"[398]

Members of high-performance teams have the right mix of skills, including technical, problem-solving, decision-making, and interpersonal skills. A high-performance team has strong core values that help guide team members' attitudes and behaviors in directions consistent with the team's purpose. Such values act as an internal control system for a group or team that can substitute for outside direction and supervisory attention.

In order to create and maintain high-performance teams, all elements of the open systems model of team effectiveness discussed in the last chapter must be addressed and successfully managed. Teamwork doesn't always happen naturally when a group of people comes together to work on a task; it is something that team members and leaders must work hard to achieve.

In the sports world coaches and managers spend a lot of time at the start of each season to join new members with old ones and form a strong team. Yet we all know that even the most experienced teams can run into problems as a season progresses. Members slack off or become disgruntled with one another; some have performance "slumps" and others criticize them for it; some are traded gladly or unhappily to other teams. Even world-champion teams have losing streaks, and the most talented players can lose motivation at times, quibble among themselves, and end up contributing little to team success. When these things happen, concerned owners, managers, and players are apt to examine their problems, take corrective action to rebuild the team, and restore the teamwork needed to achieve high-performance results.[399]

Workgroups and teams face similar challenges. When newly formed, they must master many challenges as members learn how to work together while passing through the stages of team development. Even when mature, most work teams encounter problems of insufficient teamwork at different points in time. At the very least we can say that teams sometimes need help to perform well and that teamwork always needs to be nurtured. This is why a process known as team-building is so important. It is a sequence of planned activities designed to gather and analyze data on the functioning of a team and to initiate changes designed to improve teamwork and increase team effectiveness.[400] When done well and at the right times, team-building is an effective way to deal with teamwork problems or to help prevent them from occurring in the first place.

The action steps for team-building are highlighted in Figure 8.1. Although it is tempting to view the process as something that consultants or outside experts are hired to do, the fact is that it can and should be part of any team leader and manager's action repertoire. Team-building begins when someone notices an actual or a potential problem with team effectiveness. Data is gathered to examine the problem. This can be done by questionnaire, interview, nominal group meeting, or other creative methods. The goal is to get good answers to such questions as: "How well are we doing in terms of task accomplishment?" "How satisfied are we as individuals with the group and the way it operates?" Members then work together to analyze the data, plan for improvements, and implement the action plans.

Note that the entire team-building process is highly collaborative. Everyone is expected to participate actively as team functioning is assessed and decisions are made on what needs to be done to improve team performance in the future.

Team-building can be accomplished in a wide variety of ways. In the formal retreat approach, team-building takes place during an off-site "retreat." The agenda, which may cover from one to several days, is designed to engage team members in a variety of assessment and planning tasks. These are initiated by a review of team functioning using data gathered through survey, interviews, or other means. Formal retreats are often held with the assistance of a consultant, who is either hired from the outside or made available from in-house staff. Team-building retreats offer opportunities for intense and concentrated efforts to examine group accomplishments and operations.

The outdoor experience approach is an increasingly popular team-building activity that may be done on its own or in combination with other approaches. It places group members in a variety of physically challenging situations that must be mastered through teamwork, not through individual work. By having to work together in the face of difficult obstacles, team members are supposed to experience increased self-confidence, more respect for others' capabilities, and a greater commitment to teamwork. On one fall day, for example, a team of employees from American Electric Power (AEP) went to an outdoor camp for a day of team-building activities. They worked on problems like how to get six members through a spider-web maze of bungee cords strung 2 feet above the ground. When her colleagues lifted Judy Gallo into their hands to pass her over the obstacle, she was nervous. But a trainer told the team this was just like solving a problem together at the office. The spider Web was just another performance constraint, like the difficult policy issues or financial limits they might face at work. After "high-fives" for making it through the Web, Judy's team jumped tree stumps together, passed hula hoops while holding hands, and more. Says one team trainer, "We throw clients into situations to try and bring out the traits of a good team."[401]

Not all team-building is done at a formal retreat or with the assistance of outside consultants. In a continuous improvement approach, the manager, team leader, or group members themselves take responsibility for regularly engaging in the team-building process. This method can be as simple as periodic meetings that implement the team-building steps; it can also include self-managed formal retreats. In all cases, the team members commit themselves to continuously monitoring group development and accomplishments and making the day-to-day changes needed to ensure team effectiveness. Such continuous improvement of teamwork is essential to the themes of total quality and total service management so important to organizations today.

As more and more jobs are turned over to teams, and as more and more traditional supervisors are asked to function as team leaders, special problems relating to team processes may arise. Team leaders and members alike must be prepared to deal positively with such issues as introducing new members, handling disagreements on goals and responsibilities, resolving delays and disputes when making decisions, reducing friction, and dealing with interpersonal conflicts. These are all targets for team-building. And given the complex nature of group dynamics, team-building is, in a sense, never finished. Something is always happening that creates the need for further leadership efforts to help improve team processes.

Special difficulties are likely to occur when members first get together in a new group or team, or when new members join an existing team. Problems arise as new members try to understand what is expected of them while dealing with the anxiety and discomfort of a new social setting. New members, for example, may worry about the following issues.

Participation—"Will I be allowed to participate?"

Goals—"Do I share the same goals as others?"

Control—"Will I be able to influence what takes place?"

Relationships—"How close do people get?"

Processes—"Are conflicts likely to be upsetting?"

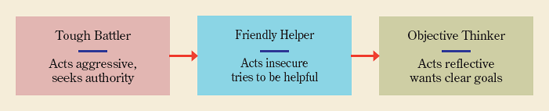

Edgar Schein points out that people may try to cope with individual entry problems in self-serving ways that may hinder team development and performance.[402] He identifies three behavior profiles that are common in such situations.

The tough battler is frustrated by a lack of identity in the new group and may act aggressively or reject authority. This person wants answers to this question: "Who am I in this group?" The best team response may be to allow the new member to share his or her skills and interests, and then have a discussion about how they can best be used to help the team. The friendly helper is insecure, suffering uncertainties of intimacy and control. This person may show extraordinary support for others, behave in a dependent way, and seek alliances in subgroups or cliques. The friendly helper needs to know whether he or she will be liked. The best team response may be to offer support and encouragement while encouraging the new member to be more confident in joining team activities and discussions. The objective thinker is anxious about how personal needs will be met in the group. This person may act in a passive, reflective, and even single-minded manner while struggling with the fit between individual goals and group directions. The best team response may be to engage in a discussion to clarify team goals and expectations, and to clarify member roles in meeting them.

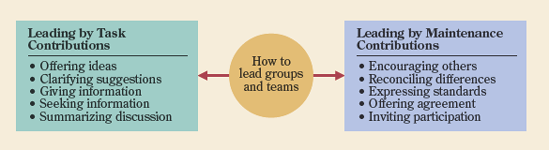

Research in social psychology suggests that teams have both "task needs" and "maintenance needs," and that both must be met for teams to be successful.[403] Even though a team leader should be able to meet these needs at the appropriate times, each team member is responsible as well. This sharing of responsibilities for making task and maintenance contributions that move a group forward is called distributed leadership, and it is usually well evidenced in high-performance teams.

Figure 8.2 describes task activities as the various things team members and leaders do that directly contribute to the performance of important group tasks. They include initiating discussion, sharing information, asking information of others, clarifying something that has been said, and summarizing the status of a deliberation.[404] A team will have difficulty accomplishing its objectives when task activities are not well performed. In an effective team, by contrast, members pitch in to contribute important task leadership as needed.

The figure also shows that maintenance activities support the social and interpersonal relationships among team members. They help a team stay intact and healthy as an ongoing and well-functioning social system. A team member or leader can contribute maintenance leadership by encouraging the participation of others, trying to harmonize differences of opinion, praising the contributions of others, and agreeing to go along with a popular course of action. When maintenance leadership is poor, members become dissatisfied with one another, the value of their group membership diminishes, and emotional conflicts may drain energies otherwise needed for task performance. In an effective team, by contrast, maintenance activities support the relationships needed for team members to work well together over time.

In addition to helping meet a group's task and maintenance needs, team members share additional responsibility for avoiding and eliminating any disruptive behaviors that harm the group process. These dysfunctional activities include bullying and being overly aggressive toward other members, withdrawing and refusing to cooperate with others, horsing around when there is work to be done, using the group as a forum for self-confession, talking too much about irrelevant matters, and trying to compete for attention and recognition. Incivility or antisocial behavior by members can be especially disruptive of team dynamics and performance. Research shows that persons who are targets of harsh leadership, social exclusion, and harmful rumors often end up working less hard, performing less well, being late and absent more, and reducing their commitment.[405]

In groups and teams, new and old members alike need to know what others expect of them and what they can expect from others. A role is a set of expectations associated with a job or position on a team. When team members are unclear about their roles or experience conflicting role demands, performance problems can occur. Although this is a common problem, it can be managed through awareness of role dynamics and their causes. Simply put, teams tend to perform better when their members have clear and realistic expectations regarding their tasks and responsibilities.

A role is a set of expectations for a team member or person in a job.

Role ambiguity occurs when a person is uncertain about his or her role in a job or on a team. In new group or team situations, role ambiguities may create problems as members find that their work efforts are wasted or unappreciated by others. Even in mature groups and teams, the failure of members to share expectations and listen to one another may, at times, create a similar lack of understanding.

Role ambiguity occurs when someone is uncertain about what is expected of him or her.

Being asked to do too much or too little as a team member can also create problems. Role overload occurs when too much is expected and someone feels overwhelmed. Role underload is just the opposite; it occurs when too little is expected and the individual feels underused. Both role overload and role underload can cause stress, dissatisfaction, and performance problems.

Role overload occurs when too much work is expected of the individual.

Role underload occurs when too little work is expected of the individual.

Role conflict occurs when a person is unable to meet the expectations of others. The individual understands what needs to be done but for some reason cannot comply. The resulting tension is stressful, and can reduce satisfaction; it can affect an individual's performance and relationships with other group members. There are four common forms of role conflict that people at work and in teams can experience.

Role conflict occurs when someone is unable to respond to role expectations that conflict with one another.

Intrasender role conflict occurs when the same person sends conflicting expectations. Example: Team leader—"You need to get the report written right away, but I need you to help me with the Power Point presentation."

Intersender role conflict occurs when different people signal conflicting and mutually exclusive expectations. Example: Team leader (to you)—"Your job is to criticize our decisions so that we don't make mistakes." Team member (to you)—"You always seem so negative, can't you be more positive for a change?"

Person-role conflict occurs when a person's values and needs come into conflict with role expectations. Example: Other team members (showing agreement with each other)—"We didn't get enough questionnaires back, so quickly everyone just make up two additional ones." You (to yourself)—"Mmm, I don't think this is right."

Inter-role conflict occurs when the expectations of two or more roles held by the same individual become incompatible, such as the conflict between work and family demands. Example: Team leader—"Don't forget the big meeting we have scheduled for Thursday evening." You (to yourself)—"But my daughter is playing in her first little-league soccer game at that same time."

A technique known as role negotiation is a helpful team-building activity for managing role dynamics. This is a process in which team members meet to discuss, clarify, and agree upon the role expectations each holds for the other. Such a negotiation might begin, for example, with one member writing down this request of another: "If you were to do the following, it would help me to improve my performance on the team." Her list of requests might include such things as: "respect it when I say that I can't meet some evenings because I have family obligations to fulfill"—indicating role conflict; "stop asking for so much detail when we are working hard with tight deadlines"—indicating role overload; and "try to make yourself available when I need to speak with you to clarify goals and expectations"—indicating role ambiguity.

The role dynamics we have just discussed develop in large part from conflicts and concerns regarding what team members expect of one another and of themselves. This brings up the issue of team norms—the ideas or beliefs about how members are expected to behave. They can be considered as rules or standards of conduct that are supposed to guide team members.[406] Norms help members to guide their own behavior and predict what others will do. When someone violates a team norm, other members typically respond in ways that are aimed at enforcing it and bringing behavior back into alignment with the norm. These responses may include subtle hints, direct criticisms, or reprimands; at the extreme someone violating team norms may be ostracized or even be expelled.

Norms are rules or standards for the behavior of group members.

Types of Team Norms A key norm in any team setting is the performance norm that conveys expectations about how hard team members should work and what the team should accomplish. In some teams the performance norm is strong; there is no doubt that all members are expected to work very hard, that high performance is the goal, and if someone slacks off they get reminded to work hard or end up removed from the team. In other teams the performance norm is weak; members are left to work hard or not as they like, with little concern expressed by the other members.

The best case for any manager is to be leading work teams with high performance norms. But many other norms also influence the day-to-day functioning of teams. In order for a task force or a committee to operate effectively, for example, norms regarding attendance at meetings, punctuality, preparedness, criticism, and social behavior are needed. Teams also commonly have norms regarding how to deal with supervisors, colleagues, and customers, as well as norms establishing guidelines for honesty and ethical behaviors. You can often find norms being expressed in everyday conversations. The following examples show the types of norms that operate with positive and negative implications for teams and organizations.[407]

Ethics norms—"We try to make ethical decisions, and we expect others to do the same" (positive); "Don't worry about inflating your expense account; everyone does it here" (negative).

Organizational and personal pride norms—"It's a tradition around here for people to stand up for the company when others criticize it unfairly" (positive); "In our company, they are always trying to take advantage of us" (negative).

High-achievement norms—"On our team, people always try to work hard" (positive); "There's no point in trying harder on our team; nobody else does" (negative).

Support and helpfulness norms—"People on this committee are good listeners and actively seek out the ideas and opinions of others" (positive); "On this committee it's dog-eat-dog and save your own skin" (negative).

Improvement and change norms—"In our department people are always looking for better ways of doing things" (positive); "Around here, people hang on to the old ways even after they have outlived their usefulness" (negative).

How to Influence Team Norms There are several things managers and team leaders can do to help their teams develop and operate with positive norms, ones that foster high performance as well as membership satisfaction. The first thing is to always act as a positive role model. In other words, the team leader should be the exemplar of the norm; always demonstrating it in his or her everyday behavior as part of the team. It is helpful to hold meetings where time is set aside for members to discuss team goals and also discuss team norms that can best contribute to their achievement. Norms are too important to be left to chance; the more directly they are discussed and confronted in the early stages of team development the better.

Team leaders should always try to select members who can and will live up to the desired norms; they should provide training and support so that members are able to live up to them; and they should reward and positively reinforce desired behaviors. This is a full-cycle approach to team norm development—select the right people, give them training and support, and then make sure that rewards and positive reinforcements are contingent on doing the right things while on the team. Finally, team leaders should hold regular meetings to discuss team performance and plan how to improve it in the future.

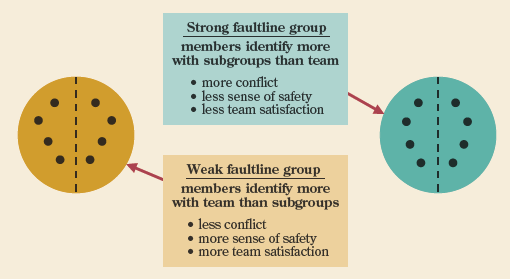

The cohesiveness of a group or team is the degree to which members are attracted to and motivated to remain part of it.[408] We might think of it as the "feel good" factor that causes people to value their membership on a team, positively identify with it, and strive to maintain positive relationships with other members. Because cohesive teams are such a source of personal satisfaction, their members tend to display fairly predictable behaviors that differentiate them from members of less cohesive teams—they are more energetic when working on team activities, less likely to be absent, less likely to quit the team, and more likely to be happy about performance success and sad about failures. Cohesive teams are able to satisfy a broad range of individual needs, often providing a source of loyalty, security, and esteem for their members.

Cohesiveness is the degree to which members are attracted to a group and motivated to remain a part of it.

Team Cohesiveness and Conformity to Norms Even though cohesive groups are good for their members, they may or may not be good for the organization. The issue is performance: will the cohesive team also be a high-performance team? The answer to this question depends on the match of cohesiveness with performance norms. And the guiding rule of conformity in team dynamics is: The greater the cohesiveness of a team, the greater the conformity of members to team norms. You can remember it this way:

Figure 8.3 shows the performance implications of this rule of conformity. When the performance norms are positive in a highly cohesive work group or team, the resulting conformity to the norm should have a positive effect on both team performance and member satisfaction. This is a best-case situation for team members, the team leader, and the organization. When the performance norms are negative in a highly cohesive group, however, the same power of conformity creates a worst-case situation for the team leader and the organization. Although the high cohesiveness leaves the team members feeling loyal and satisfied, they are also highly motivated to conform to the negative performance norm. In this situation the team is good for the members but performs poorly. In between these two extremes are two mixed-case situations for teams low in cohesion. Because there is little conformity to either the positive or negative norm, member behaviors will vary and team performance will most likely fall on the moderate or low side.

How to Influence Team Cohesiveness What can a manager or team leader do to tackle the worst-case and mixed-case scenarios just described? The answer rests with some basic understandings about the factors influencing team cohesiveness. Cohesiveness tends to be high when teams are more homogeneous in make-up, that is, when members are similar in age, attitudes, needs, and backgrounds. Cohesiveness also tends to be high in teams of small size, where members respect one another's competencies, agree on common goals, and work together rather than alone on team tasks. And cohesiveness tends to increase when groups are physically isolated from others and when they experience performance success or crisis.

Figure 8.4 shows how team cohesiveness can be increased or decreased by making changes in such things as goals, membership composition, interactions, size, rewards, competition, location, and duration. When the team norms are positive but cohesiveness is lacking, the goal is to take actions to increase cohesion and gain more conformity to the positive norms. But when team norms are negative and cohesiveness is high, just the opposite may have to be done. The goal in this situation is to reduce cohesiveness and thus reduce conformity to the negative norms. Finally, it should be remembered that team norms can be positively influenced to harness the power of conformity in teams that are already cohesive or in those where cohesion is being rebuilt or strengthened.

In the prior discussion it was pointed out that the presence of competition with other teams tends to create more cohesiveness within a team. This raises the issue of what happens between, not just within, teams. The term inter-team dynamics refers to the dynamics that take place between two or more teams in these and other similar situations. Organizations ideally operate as cooperative systems in which the various components support one another. In the real world, however, competition and inter-team problems often develop within an organization and with mixed consequences.

Inter-team dynamics are relationships between groups cooperating and competing with one another.

On the negative side, such as when manufacturing and sales units don't get along, between-team dynamics may drain and divert energies because members spend too much time focusing on their animosities or conflicts with another team than on the performance of their own.[409] On the positive side, competition among teams can stimulate them to become more cohesive, work harder, become more focused on key tasks, develop more internal loyalty and satisfaction, or achieve a higher level of creativity in problem solving. This effect is demonstrated at virtually any intercollegiate athletic event, and it is common in work settings as well. Sony, for example, once rallied its workers around the slogan: "Beat Matsushita whatsoever."[410]

A variety of steps can be taken to avoid negative and achieve positive effects from inter-team dynamics. Teams engaged in destructive competition, for example, can be refocused on a common enemy or a common goal. Direct negotiations can be held among the teams. Members can also be engaged in intergroup team-building that brings about positive interactions and through which the members of different teams learn how to work more cooperatively together. Reward systems can also be refocused to emphasize team contributions to overall organizational performance and on how much teams help out one another.

In Chapter 11 on communication and collaboration we provide extensive coverage of basic issues in interpersonal and organizational communication. The focus there is on such things as communication effectiveness, techniques for overcoming barriers and improving communication, information flows within organizations, and the use of collaborative communication technologies. And in teams, it is important to make sure that every member is strong and capable in basic communication and collaboration skills as discussed in Chapter 11. When the focus is on communication as a team process, the team-building questions are: What communication networks are being used by the team and why? How does space affect communication among team members? Is the team making good use of the available communication technologies?

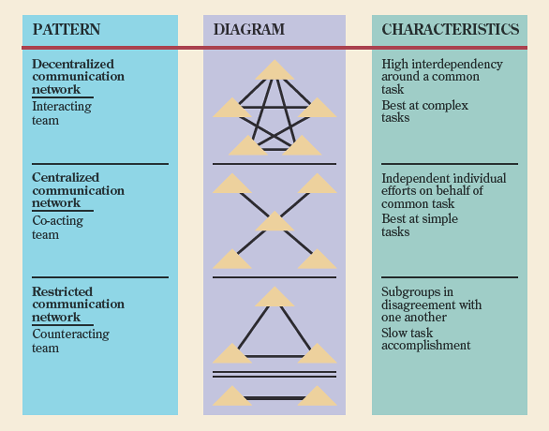

Three patterns typically emerge when team members interact with one another while working on team tasks—the interacting team, the co-acting team, and the counteracting team. Each is associated with a different communication network as shown in Figure 8.5.[411]

In order for a team to be effective and high-performing, the interaction pattern and communication network should fit well with the task at hand, ideally with the patterns and networks shifting as task demands develop and change over time. In fact, one of the most common mistakes discovered during team-building is that teams are not using the right interaction patterns and communication networks as they try to accomplish various tasks. An example might be a student project team whose members believe every member must always be present when any work gets done on the project; in other words, no one works on their own and everything is done together.

When task demands require intense interaction, this is best done with a decentralized communication network. Also called the star network or all-channel network, the basic characteristic is that everyone communicates as needed with everyone else; information flows back and forth constantly, with no one person serving as the center point.[412] This creates an interacting team in which all members communicate directly and share information with one another. Figure 8.5 indicates that decentralized communication networks work best when team tasks are complex and nonroutine, perhaps ones that involve uncertainty and require creativity. With success, member satisfaction on interacting teams is usually high.

In decentralized communication networks members communicate directly with one another.

When task demands allow for more independent work by team members, a centralized communication network is the best option. Also called the wheel network or chain network, its basic characteristic is the existence of a central "hub" through which one member, often the team leader, collects and distributes information among the other members. Members of such coaching teams work on assigned tasks independently while the hub keeps everyone linked together through some form of central coordination. Teams operating in this fashion divide up the work among members, who then work independently to complete their assigned tasks; results are passed to the hub member and pooled to create the finished product. The centralized network works best when team tasks are routine and easily subdivided. It is usually the hub member who experiences the most satisfaction on successful coaching teams.

Counteracting teams form when subgroups emerge within a team due to issue-specific disagreements, such as a temporary debate over the best means to achieve a goal, or emotional disagreements, such as personality clashes. In both cases a restricted communication network forms in which the subgroups contest each other's positions and restrict interactions with one another. The poor communication characteristic of such situations often creates problems, although there are times when counteracting teams might be set up to provide conflict and critical evaluation to help test out specific decisions or chosen courses of action.

An important but sometimes neglected part of communication in teams involves proxemics, or the use of space as people interact.[413] We know, for example, that office or workspace architecture is an important influence on communication behavior. It only makes sense that communication in teams might be improved by either arranging physical space to best support it, like moving chairs and tables into proximity with one another, or by choosing to meet in physical spaces that are conducive to communication, such as meeting in a small conference room in the library or classroom building rather than a busy coffee shop.

Proxemics involves the use of space as people interact.

Architects and consultants specializing in office design help executives build spaces conducive to the intense communication and teamwork needed today. When Sun Microsystems built its San Jose, California, facility, public spaces were designed to encourage communication among persons from different departments. Many meeting areas had no walls, and most walls were glass.[414] At Google headquarters, often called Googleplex, specially designed office "tents" are made of acrylics to allow both the sense of private personal space and transparency.[415] And at b&a advertising in Dublin, Ohio, an emphasis on open space supports the small ad agency's emphasis on creativity; after all, its Web address is www.babrain.com. Face-to-face communication is the rule at b&a to the point where internal e-mail among employees is banned. There are no offices or cubicles, and all office equipment is portable. Desks have wheels so that informal meetings can happen by people repositioning themselves for spontaneous collaboration. Even the formal meetings are held standing up in the company kitchen.[416]

It hardly seems necessary in the age of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube to mention that teams now have access to many useful technologies that can facilitate communication and break down the need to be face-to-face all or most of the time. We live and work in an age of instant messaging, individual–individual and group chats, e-mail and voice-mail, tweets and texting, wikis, online discussions, videoconferencing, and more. We are networked socially 24–7 to the extent we want, and there's no reason the members of a team can't utilize the same technologies to good advantage.

In effect we can think of technology as allowing and empowering teams to use virtual communication networks in which team members can always be in electronic communication with one another as well as with a central database. In effect the team works in both physical space and in virtual space, with the results achieved in each contributing to overall team performance. Technology, such as an online discussion forum, acts as the "hub member" in the centralized communication network; simultaneously, through chats and tweets and more, it acts as an ever-present "electronic router" that links members of decentralized networks on an as-needed and always-ready basis. General Electric, for example, started a "Tweet Squad" to advise employees how social networking could be used to improve internal collaboration; the insurer MetLife has its own social network, connect. MetLife, which facilitates collaboration through a Facebook-like setting.[417]

Of course, and as mentioned in the last chapter, there are certain steps that need to be taken to make sure that virtual teams and communication technologies are as successful as possible—things like doing online team-building so that members get to know one another, learn about and identify team goals, and otherwise develop a sense of cohesiveness.[418] And we shouldn't forget the protocols and just everyday "manners" of using technology as part of teamwork. For example, Richard Anderson, CEO of Delta Airlines, says: "I don't think it's appropriate to use Blackberrys in meetings. You might as well have a newspaper and open the newspaper up in the middle of the meeting."[419] Might we say the same for the classroom?

One of the most important activities for any team is decision making, the process of choosing among alternative courses of action. The topic is so important that the entire next chapter is devoted to it. There is no doubt that the quality and timeliness of decisions made and the processes through which they are arrived at can have an important impact on team effectiveness. One of the issues addressed in team-building is how a team goes about making decisions and whether or not these choices are good or bad for team performance.

Decision making is the process of choosing among alternative courses of action.

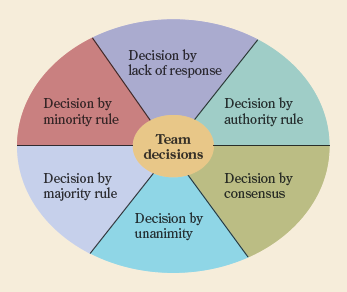

Consider the many teams of which you have been and are a part. Just how do major decisions get made? Most often there's a lot more going on than meets the eye. Edgar Schein, a noted scholar and consultant, has worked extensively with teams to identify, analyze, and improve their decision processes.[420] He observes that teams may make decisions through any of the six methods shown in Figure 8.6—lack of response, authority rule, minority rule, majority rule, consensus, or unanimity. Schein doesn't rule out any method, but he does point out the disadvantages that teams suffer when decisions are made without high levels of member involvement.

Lack of Response In decision by lack of response, one idea after another is suggested without any discussion taking place. When the team finally accepts an idea, all others have been bypassed and discarded by simple lack of response rather than by critical evaluation. This may be most common early in a team's development when new members are struggling to find their identities and confidence in team deliberations; it's also common in teams with low-performance norms and when members just don't care enough to get involved in what is taking place. But whenever lack of response drives decisions, it's relatively easy for a team to move off in the wrong, or at least not the best, direction.

Authority Rule In decision by authority rule, the chairperson, manager, or leader makes a decision for the team. This can be done with or without discussion and contributions by other members and is very time efficient. Whether the decision is a good one or a bad one depends on whether the authority figure has the necessary information and on how well other group members accept this approach. When the authority is also an expert, this decision approach can work well, assuming other members are willing to commit to the direction being set. But when an authority decision is made without expertise or member commitment, problems are likely.

Minority Rule In decision by minority rule, two or three people are able to dominate, or "railroad," the group into making a decision with which they agree. This is often done by providing a suggestion and then forcing quick agreement by challenging the group with such statements as: "Does anyone object? ... No? Well, let's go ahead then." While such forcing and bullying may get the team moving in a certain direction, the likelihood is that member commitment to making the decision successful will be low; "kickback" and "resistance," especially when things get difficult, aren't unusual in these situations.

Majority Rule One of the most common ways that groups make decisions is decision by majority rule. This usually takes place as a formal vote with members being polled publicly or confidentially to find the majority viewpoint. This method parallels the democratic political system and is often used without awareness of its potential problems. It's also common when team members get into disagreements that seem irreconcilable; voting is seen to be an easy way out of the situation. But the very process of voting creates coalitions, especially when the voting is close. That is, some team members will turn out to be "winners" and others will be "losers" after votes are tallied. Those in the minority—the "losers"—may feel left out or discarded without having had a fair say. As a result, they may be less enthusiastic about implementing the decision of the "winners." And their lingering resentments may impair team effectiveness in the future as they become more concerned about winning the next vote than doing what is best for the team as a whole.

Consensus Another decision alternative is consensus. Formally defined, decision by consensus occurs when discussion leads to one alternative being favored by most team members and the other members agreeing to support it. When a consensus is reached, even those who may have opposed the chosen course of action know that they have been listened to and have had a fair chance to influence the outcome. Consensus does not require unanimity. What it does require, as pointed out in Mastering Management, is the opportunity for any dissenting members to feel that they have been able to speak and that their voices have been heard.[421] Because of the extensive process involved in reaching a consensus decision, it may be inefficient from a time perspective, but it is very powerful in terms of generating commitments among members to making the final decision work best for the team.

Consensus is a group decision that has the expressed support of most members.

Unanimity A decision by unanimity may be the ideal state of affairs. Here, all team members agree totally on the course of action to be taken. This is a "logically perfect" decision situation that is extremely difficult to attain in actual practice. One reason that teams sometimes turn to authority decisions, majority voting, or even minority decisions, in fact, is the difficulty of managing the team process to achieve decisions by consensus or unanimity.

Just as with communication networks, the best teams don't limit themselves to any one of the decision methods just described. More likely, they move back and forth among them but somehow tend to use each in circumstances that are most appropriate. In our cases for example, we never complain when a department head makes an authority decision to have a welcome reception for new majors at the start of the academic year or to call for a faculty vote on a proposed new travel policy—things we are content to "leave to the boss" so to speak. Yet, we are quick to disapprove when a department head makes an authority decision to hire a new faculty member—something we believe should be made by consensus.

The key for our department head and any team leader is to use and support decision methods that best fit the problems and situations at hand. Achieving the goal of making timely and quality decisions to which the members are highly committed, however, always requires a good understanding of the potential assets and liabilities of decision making.[422] On the positive side, the more team-oriented decision methods, such as consensus and unanimity, offer the advantages of bringing more information, knowledge, and expertise to bear on a problem. The discussion tends to create broader understanding of the final decision; this, in turn, increases acceptance and strengthens the commitments of members to follow through and support the decision. But on the negative side, the "team" aspect of such decisions can be imperfect. Social pressures to conform might make some members unwilling to go against or criticize what appears to be the will of the majority. In the guise of a team decision, furthermore, a team leader or a few members might "railroad" or "force" other members to accept their preferred decision. And there is a time cost to the more deliberative team decision methods. Simply put, it usually takes a team longer to make a decision than it does an individual.

An important potential problem that arises when teams try to make decisions is groupthink—the tendency of members in highly cohesive groups to lose their critical evaluative capabilities.[423] As identified by social psychologist Irving Janis, group-think is a property of highly cohesive teams, and it occurs because team members seek conformity and become unwilling to criticize each other's ideas and suggestions. Desires to hold the team together, feel good, and avoid unpleasant disagreements bring about an overemphasis on agreement and an underemphasis on critical discussion. According to Janis, the result often is a poor decision.

Groupthink is the tendency of cohesive group members to lose their critical evaluative capabilities.

By way of historical examples Janis suggests that groupthink played a role in the lack of preparedness by U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor before the United States' entry into World War II. It has also been linked to flawed U.S. decision making during the Vietnam War, to events leading up to the space shuttle disasters, and, most recently, to failures of American intelligence agencies regarding the status of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Against this context, the following symptoms of teams displaying groupthink should be well within the sights of any team leader and member.[424]

Illusions of invulnerability—Members assume that the team is too good for criticism or beyond attack.

Rationalizing unpleasant and disconfirming data—Members refuse to accept contradictory data or to thoroughly consider alternatives.

Belief in inherent group morality—Members act as though the group is inherently right and above reproach.

Stereotyping competitors as weak, evil, and stupid—Members refuse to look realistically at other groups.

Applying direct pressure to deviants to conform to group wishes —Members refuse to tolerate anyone who suggests the team may be wrong.

Self-censorship by members—Members refuse to communicate personal concerns to the whole team.

Illusions of unanimity—Members accept consensus prematurely, without testing its completeness.

Mind guarding—Members protect the team from hearing disturbing ideas or outside viewpoints.

There is no doubt that groupthink is a serious threat to the quality of decision making in teams at all levels and in all types of organizations. Team leaders and members alike should be alert to its symptoms and be quick to take any necessary action to prevent its occurrence.[425] For example, President Kennedy chose to absent himself from certain strategy discussions by his cabinet during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This reportedly facilitated critical discussion and avoided tendencies for members to try to figure out what the president wanted and then give it to him. As a result the decision-making process was open and expansive, and the crisis was successfully resolved. Richard Anderson, Delta's CEO, follows a similar strategy to try to avoid groupthink in his executive team. Although he attends the meetings, he takes care to avoid groupthink. "I tend to be a stoic going into the meeting," he says. "I want the debate. I want to hear everybody's perspective, so you try to ask more questions than make statements."[426] OB Savvy 8.2 identifies a number of steps that teams and their leaders can take to avoid groupthink or at least minimize its occurrence.

In order to take full advantage of the team as a decision-making resource, care should be exercised to avoid groupthink and otherwise manage problems in team dynamics.[427] Team process losses often occur, for example, when meetings are poorly structured or poorly led as members try to work together. When tasks are complex, information is uncertain, creativity is needed, time is short, "strong" voices are dominant, and debates turn emotional and personal, decisions can easily get bogged down or go awry. Fortunately, there are some team decision techniques that can be helpful in such situations.[428]

Brainstorming In brainstorming, team members actively generate as many ideas and alternatives as possible, and they do so relatively quickly and without inhibitions. IBM, for example, uses online brainstorming as part of a program called Innovation Jam. It links IBM employees, customers, and consultants in an "open source" approach. Says CEO Samuel J. Palmisano: "A technology company takes its most valued secrets, opens them up to the world and says, O.K., world, you tell us what to do with them."[429]

brainstorming involves generating ideas through "freewheeling" and without criticism.

You are probably familiar with the rules that typically govern the brainstorming process. First, all criticism is ruled out. No one is allowed to judge or evaluate any ideas until the idea generation process has been completed. Second, "freewheeling" is welcomed. The emphasis is on creativity and imagination; the wilder or more radical the ideas, the better. Third, quantity is wanted. The emphasis is also on the number of ideas; the greater the number, the more likely a superior idea will appear. Fourth, "piggy-backing" is good. Everyone is encouraged to suggest how others' ideas can be turned into new ideas or how two or more ideas can be joined into still another new idea.

Nominal Group Technique In any team there will be times when the opinions of members differ so much that antagonistic arguments will develop during discussions. At other times the team is so large that open discussion and brain-storming are awkward to manage. In such cases a structured approach called the nominal group technique may be helpful, and it can be done face-to-face or in a computer-mediated meeting.[430]

The nominal group technique involves structured rules for generating and prioritizing ideas.

The technique begins by asking team members to respond individually and in writing to a nominal question, such as: "What should be done to improve the effectiveness of this work team?" Everyone is encouraged to list as many alternatives or ideas as they can. Next, participants in round-robin fashion are asked to read aloud their responses to the nominal question. A recorder writes each response on large newsprint or in a computer database as it is offered. No criticism is allowed. The recorder asks in round-robin fashion for any questions that may clarify specific items on the list, but no evaluation is allowed; the goal is simply to make sure that everyone present fully understands each response. A structured voting procedure is then used to prioritize responses to the nominal question and arrive at the choice or choices with the most support. This nominal group procedure allows ideas to be evaluated without risking the inhibitions, hostilities, and distortions that may occur in an open and unstructured team meeting.

Delphi Technique The Rand Corporation developed a third group-decision approach, the Delphi Technique, for situations when group members are unable to meet face-to-face. In this procedure, questionnaires are distributed online or in hard copy to a panel of decision makers, who submit initial responses to a decision coordinator. The coordinator summarizes the solutions and sends the summary back to the panel members, along with a follow-up questionnaire. Panel members again send in their responses, and the process is repeated until a consensus is reached and a clear decision emerges.

These learning activities from The OB Skills Workbook are suggested for Chapter 8.

Cases for Critical Thinking | Team and Experiential Exercises | Self-Assessment Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 8 Study guide: Summary Questions and Answers

How can we create high-performance teams?

Team-building is a collaborative approach to improving group process and performance.

High-performance teams have core values, clear performance objectives, the right mix of skills, and creativity.

Team-building is a data-based approach to analyzing group performance and taking steps to improve performance in the future.

Team-building is participative and engages all group members in collaborative problem solving and action.

How can team processes be improved?

Individual entry problems are common when new teams are formed and when new members join existing teams.

Task leadership involves initiating, summarizing, and making direct contributions to the group's task agenda; maintenance leadership involves gate-keeping, encouraging, and supporting the social fabric of the group over time.

Distributed leadership occurs when team members step in to provide helpful task and maintenance activities and discourage disruptive activities.

Role difficulties occur when expectations for group members are unclear, overwhelming, underwhelming, or conflicting.

Norms are the standards or rules of conduct that influence the behavior of team members; cohesiveness is the attractiveness of the team to its members.

Members of highly cohesive groups value their membership and are very loyal to the group; they also tend to conform to group norms.

The best situation is a team with positive performance norms and high cohesiveness.

Intergroup dynamics are the forces that operate between two or more groups.

How can team communications be improved?

Effective teams use alternative communication networks and decision-making methods to best complete tasks.

Interacting groups with decentralized networks tend to perform well on complex tasks; co-acting groups with centralized networks may do well at simple tasks.

Restricted communication networks are common in counteracting groups with subgroup disagreements.

Wise choices on proxemics, or the use of space, can help teams improve communication among members.

Information technology ranging from e-mail to instant messaging, tweets, and discussion groups can improve communication in teams, but it must be well used.

How can team decisions be improved?

Teams can make decisions by lack of response, authority rule, minority rule, majority rule, consensus, and unanimity.

Although team decisions often make more information available for problem solving and generate more understanding and commitment, the potential liabilities of group decision making include social pressures to conform and greater time requirements.

Groupthink is a tendency of members of highly cohesive teams to lose their critical evaluative capabilities and make poor decisions.

Techniques for improving creativity in teams include brainstorming and the nominal group technique.

Brainstorming (p. 199)

Centralized communication network (p. 193)

Cohesiveness (p. 188)

Consensus (p. 196)

Decentralized communication network (p. 192)

Decision making (p. 195)

Delphi technique (p. 200)

Disruptive behavior (p. 185)

Distributed leadership (p. 184)

Groupthink (p. 198)

Inter-team dynamics (p. 190)

Maintenance activities (p. 184)

Nominal group technique (p. 200)

Norms (p. 186)

Proxemics (p. 194)

Restricted communication network (p. 193)

Role (p. 185)

Role ambiguity (p. 185)

Role conflict (p. 185)

Role negotiation (p. 186)

Role overload (p. 185)

Role underload (p. 185)

Rule of conformity (p. 188)

Task activities (p. 184)

Team-building (p. 181)

Virtual communication networks (p. 194)

One of the essential criteria of a true team is ____________. (a) large size (b) homogeneous membership (c) isolation from outsiders (d) collective accountability

The team-building process can best be described as participative, data-based, and ____________. (a) action-oriented (b) leader-centered (c) ineffective (d) short-term

A person facing an ethical dilemma involving differences between personal values and the expectations of the team is experiencing ____________ conflict. (a) personrole (b) intrasender role (c) intersender role (d) interrole

The statement "On our team, people always try to do their best" is an example of a(n) ____________ norm. (a) support and helpfulness (b) high-achievement (c) organizational pride (d) organizational improvement

Highly cohesive teams tend to be ____________. (a) bad for organizations (b) good for members (c) good for social loafing (d) bad for norm conformity

To increase team cohesiveness, one would ____________. (a) make the group bigger (b) increase membership diversity (c) isolate the group from others (d) relax performance pressures

A team member who does a good job at summarizing discussion, offering new ideas, and clarifying points made by others is providing leadership by contributing ____________ activities to the group process. (a) required (b) disruptive (c) task (d) maintenance

When someone is being aggressive, makes inappropriate jokes, or talks about irrelevant matters in a group meeting, these are all examples of ____________. (a) dysfunctional behaviors (b) maintenance activities (c) task activities (d) role dynamics

If you heard from an employee of a local bank that "it's a tradition here for us to stand up and defend the bank when someone criticizes it," you could assume that the bank employees had strong ____________ norms. (a) support and helpfulness (b) organizational and personal pride (c) ethical and social responsibility (d) improvement and change

What can be predicted when you know that a work team is highly cohesive? (a) high-performance results (b) high member satisfaction (c) positive performance norms (d) status congruity

When two groups are in competition with one another, ____________ may be expected within each group. (a) more in-group loyalty (b) less reliance on the leader (c) poor task focus (d) more conflict

A co-acting group is most likely to use a(n) ____________ communication network. (a) interacting (b) decentralized (c) centralized (d) restricted

A complex problem is best dealt with by a team using a(n) ____________ communication network. (a) all-channel (b) wheel (c) chain (d) linear

The tendency of teams to lose their critical evaluative capabilities during decision making is a phenomenon called ____________. (a) groupthink (b) the slippage effect (c) decision congruence (d) group consensus

When a team decision requires a high degree of commitment for its implementation, a(n) ____________ decision is generally preferred. (a) authority (b) majority-vote (c) consensus (d) railroading

Describe the steps in a typical team-building process.

How can a team leader build positive group norms?

How do cohesiveness and conformity to norms influence group performance?

How can inter-team competition be bad and good for organizations?

Alejandro Puron recently encountered a dilemma in working with his employer's diversity task force. One of the team members claimed that a task force must always be unanimous in its recommendations. "Otherwise," she said, "we will not have a true consensus." Alejandro, the current task force leader, disagrees. He believes that unanimity is desirable but not always necessary to achieve consensus. You are a management consultant specializing in using groups in organizations. Alejandro calls you for advice. What would you tell him and why?