AS I STARTED writing this book, I decided I should buy an external hard drive to backup these chapters. I went to the NewEgg.com Web site to make a purchase. It took me at least 10 visits and over three hours to make this purchase. Why? Because every time I went to visit the site, there were dozens—no, make that hundreds—of hard drives to choose from. And they were pretty much all the same. All the same size, all the same capacity, all the same price. They differed in shape and color. That purchase took me a long time.

One interesting thing about choices is that we think we want a lot of them, but in actuality, a lot of choices hinders our decision-making process. If given a choice between a few alternatives or numerous choices, we will most likely want as many choices as possible. But research shows it doesn’t help us as much as we think. This is a classic case where what we think we want (conscious brain) is just plain wrong. We really don’t make better decisions with more choices, but we think we do. Too many choices just makes us freeze and then we make no choice at all.

We say we want a lot of choices, but the reality is that when we have a lot of choices, we can’t decide.

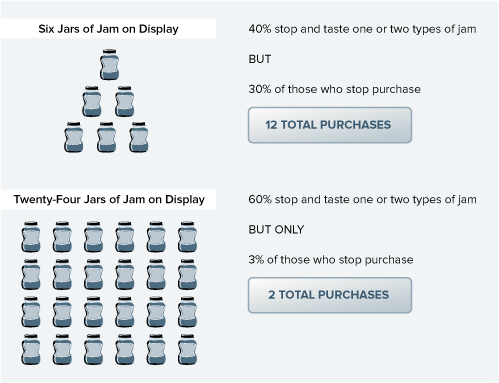

IYENGAR AND LEPPER (2000) tested the theory that if we’re provided with too many choices, we don’t choose at all. Experimenters set up booths at a busy upscale grocery store in Menlo Park, California, and posed as store employees. They alternated the product selections on the table. Half of the time, there were six choices of fruit jam for shoppers to taste. Half of the time, there were 24 jars of jam to taste.

Did it make a difference how many jars there were? Yes, it did. When there were 24 jars of jam on the table, 60 percent of shoppers passing the table stopped and tasted jam. When there were six jars of jam on the table, only 40 percent stopped to taste. So does that mean that more choices are a good thing?

But wait, there’s more.

You would think that people would taste more varieties of jam when the table had 24 flavors. But they didn’t. People tasted one to two varieties, whether there were six or 24 choices available.

And how did varying the selection influence purchases? Of the shoppers who stopped at the table with six jars, 30 percent actually purchased the brand of jam they had tried. Of those who stopped at the table with 24 jars, only three percent purchased jam.

So what do we learn from this? A bigger selection attracted a bigger crowd, but that crowd purchased fewer products than the group presented with fewer choices.

To give you an example of the numbers, if 100 shoppers came by (they actually had more than that in the study, but 100 makes the calculations easy for our purposes):

• At the table with 24 jars, 60 stopped to taste jam but only two purchased jam.

• At the table with six jars, 40 tasted jam and 12 purchased jam.

Less is more.

More jars means more people stop by, but fewer people purchase.

Lots of choices will grab our attention, but too many choices overwhelm us—to the point where we likely won’t buy at all.

A REALTOR FRIEND of mine says prospective home buyers come to her with a list of what’s important to them in buying a house, yet she doesn’t fully believe their list truly reflects what’s important to them. Her experience is that individuals fall in love with a house even though the house fails to meet many of the criteria they have on their “must have” list.

Why?

We like to think that our choices are based on a logical weighing of one choice versus another, but there is a lot of research that shows that our choices are not logical. In fact, we aren’t consciously aware of why we are choosing one item over another. And after we make a choice, we can’t even accurately explain why we made the choice we did. We will try to make up a reason, but it probably isn’t accurate.

Wilson (2002) showed people four types of pantyhose and asked them to select the type they would prefer to buy. People had definite preferences. (Most of them chose the pair that was farthest to the right on the table.) What they didn’t know was that all the pantyhose were exactly alike.

When asked why they chose the one on the far right, they provided a variety of reasons, including “it’s softer” or “it’s stronger.”

IN FACT, THERE is some research that shows that a logical analysis of a purchase, or an analysis of your likes and dislikes, may be a harmful thing to engage in.

Wilson and Kraft (1993) asked couples to analyze their relationships and write lists of why they liked the person they were involved with. Wilson then compared the longevity of the relationship in these couples to the longevity of relationships in a control group that was not asked to logically analyze their relationship. Analyzing the relationships resulted in the relationship ending sooner than the relationships where couples were not asked for an analysis.

Analyzing doesn’t just ruin relationships, but it also seems to ruin your satisfaction with the purchases you make. Wilson (1993) studied individuals buying art posters:

• Group A analyzed why they liked and didn’t like five art posters.

• Group B did not do any analysis.

Each individual in each group then picked one poster to take home. Two weeks later, researchers contacted them to see how happy they were with their choices. Those in Group B, who didn’t analyze the art they took home, were happier with their choices than those in Group A (who had analyzed their art).

Dijksterhuis and van Olden (2005) performed the study again, but they added a few twists. Participants were told the study focused on evaluating art. Everyone in the study was brought in to look at art posters, one at a time, for 15 seconds on a computer screen. Then, after looking at the posters, they were assigned to one of three conditions where they performed more tasks:

• In the Conscious Thought condition, participants looked at each poster one by one on the computer screen and were asked to analyze carefully whether they liked each poster and why or why not. They were given paper and pen to record their analyses. Then all the posters appeared on one screen, and they were asked to pick the one they liked the best.

• In the Unconscious Thought condition, participants engaged in a different task—they worked on anagrams—for the same amount of time. Then they were shown the posters again, all placed on a single screen, and asked which one they liked the best.

• In the Immediate Decision condition, participants were shown a single screen showing all the art posters and asked which poster they liked the most.

At the end of the experiment, the participants could choose a poster to take home. The researchers hypothesized that the Unconscious Thought participants (who worked on anagrams) had made their decisions unconsciously and would be most satisfied with their choices.

They were correct!

It seems that if we make our choice unconsciously, without conscious processing, then we stick with it over time. If we spend more time and logically analyze why we’re choosing what we’re choosing, we’re less satisfied over time with our choices.

YOU HAVE BEEN saving for a new car. You’ve got enough money saved to purchase a new Honda Civic. It’s a reliable car. It gets great mileage. You think it’s cute. If you save longer, you’ll be able to get the flashier Honda sports car (the S2000)—but it costs twice as much. You’d really like the S2000.

Which car will you purchase? Well, it might depend on where you are and what you are doing when you are trying to decide.

A relatively new technology called functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) lets us see into the brain while it is working. When certain parts of the brain are active, those parts will show up as colored lights on a computer display. A group of researchers (McClure et al, 2004) asked individuals to choose between certain money rewards. They could get a small amount of money ($5) now or a larger amount of money ($40) later. Researchers varied the amount of money, how difficult it was to calculate when you would get what amount, and how long participants would have to wait to get the larger amount (one week vs. two weeks).

When participants thought about waiting, and when they calculated how much they would get if they waited, the pre-frontal cortex (new brain) lit up. But when they thought about getting the money right away, the mid brain lit up—especially the area of the mid brain that involves pleasure. Apparently, our unconscious, emotional brain (mid brain) is activated when we imagine getting something that we think would be nice, pleasant, and rewarding—especially if we get It right away.

This implies that if we are making a decision about buying something, we will be swayed by whether we can have it right away. The mid brain will compete with the new brain about whether to wait.

If we are making a decision with the product right there in front of us, then we will be swayed by the product itself—the look, smell, or feel of it. Buying something on the Internet may not have that same immediacy and allure to the mid brain. In order for the mid brain to get engaged and say “now, now, now,” and in order for us to take action right away, something at the site has to get the attention of our mid brain.

IF WE SEE that we’ll get what we want right away, that will speak to the mid brain and encourage us to act.

For the mid brain, it’s all about immediacy. If the Web site can’t promise it immediately, the next best thing is to let us know it will be there very soon. Notice that in the message that follows, there is immediacy about when it will be delivered (tomorrow) and when you should order it (in the next 19 minutes).

The mid brain pays attention when it sees that it can get it by a certain date, and when there are only a few minutes left.

With sites like Apple’s iTunes, we can order and download music instantly. This is irresistible and has revolutionized how we buy music. Instead of driving to a store to purchase an entire CD, we can buy only the songs we want—instantly and with only a few clicks of a mouse.

IMAGINE THIS SCENARIO: You’ve just bought a digital camera for $689.99. Now you realize that you didn’t buy a carrying case. You don’t want to walk around with it in your pocket or bag, since it could get scratched. So you go online to shop for a camera case. Are you going to buy the nice, all-weather camera backpack for $89.95? Or are you going to save some money by purchasing a cloth case for only $9.97? The amount of $89.95 for a camera case seems a bit much. That’s because you are comparing it with a cloth camera case for $9.97.

When presented alongside much less expensive cases, the $89.95 case seems a little steep. In this case, you’ll probably choose a less expensive model.

If you had purchased the camera case when you first bought the camera, you probably would have chosen a nicer and more expensive case. In that situation, you are comparing $89.95 to the price of the $689.99 camera. Then $90 seems like a bargain compared to $689.99. And how does a $29.99 price grab you? In the example that follows, you’d likely purchase the seemingly cheap case for $29.99. And then you’ll put a logical reason on top of the decision, since you have to protect your expensive $689.99 investment.

This is an example of up-sell. In order for us to be influenced by this up-sell, the extra accessories have to appear at the time we are making the larger purchase.

The old brain is engaged if there is choice decision that involves contrast. The old brain is looking for basics. Big versus small; expensive versus inexpensive. It will make instant decisions about good and bad based on contrast.

YOU GO TO a Web site to buy a tent for camping. You answer some questions about the type of camping you plan to do. The site then recommends four tents that best match your use and compares the four tents based on 10 attributes (how waterproof they are, how much they weigh, how much air ventilation they have, and so on). Two of the four tents are “best buys” for the attributes that are important to you. Which tent will you buy?

Felfernig (2007) set up a research study to find out. Even though there were 10 attributes that the tents were compared on, participants focused only on two or three attributes. The researchers varied the order in which the tents appeared on the page: first, second, third, or fourth. It turns out that the most important attribute was not whether the tent was waterproof or if it had plenty of air ventilation. The most important attribute was the order in which the tents appeared on the page! Participants disregarded attributes and simply picked whichever tent was the first one to show on-screen. In fact, they picked the first tent 2.5 times more than any other. They chose the first tent 200 times; they chose the other three tents (combined) only 60 times. This is called an order effect.

The participants explained their choices, however, based on the logical decisions they thought they were making. For example, they explained the choice of tent #1 by saying, “This tent is the most waterproof.” They thought they were weighing all the attributes of all the tents, but in reality they were considering only a few attributes—and even those attributes didn’t matter. All that mattered was an unconscious reaction to which tent showed up first.

If you have a Web site, look carefully at the algorithms of what products appear in which order. Make sure the first item is the one you’d like to sell the most.