Chapter 1

Recording and Running Macros in the Office Applications

In this first chapter, you'll explore the easiest way to get started with Visual Basic for Applications (VBA): recording simple macros using the Macro Recorder that's built into the Office applications. Then you'll see how to run your macros to perform useful tasks.

I'll define the term macro in a moment. For now, just note that by recording macros, you can automate straightforward but tediously repetitive tasks and speed up your regular work. You can also use the Macro Recorder to create VBA code that performs the actions you need and then edit the code to customize it—adding flexibility and power. In fact, VBA is a real powerhouse if you know how to use it. This book shows you how to tap into that power.

What Is VBA and What Can You Do with It?

Visual Basic for Applications is a programming language created by Microsoft that is built into applications. You use VBA to automate operations in all the main Office applications—Word, Excel, Outlook, Access, and PowerPoint.

But please don't be put off by the notion that you'll be programming; as you'll see shortly, working with VBA is nearly always quite easy. In fact, often you need not actually write any VBA yourself; you can merely record it—letting the Office application write all the VBA “code.”

The phrase automate operations in applications is perhaps a bit abstract. So here are a few examples of how to use VBA to streamline tasks, avoid burdensome repetition, customize the applications' interfaces, and in general improve your efficiency:

- You can record a macro that automatically carries out a series of actions that you frequently perform. Let's say that you often edit Word documents written by a co-worker, but she sets the zoom level to 100. You prefer to zoom 150. All you need to automatically change the zoom level is this VBA code:

ActiveWindow.ActivePane.View.Zoom.Percentage = 150

You could even put the code into a special location in Word that will automatically execute this zoom for every document you open:

Sub AutoOpen()ActiveWindow.ActivePane.View.Zoom.Percentage = 150End Sub

And don't worry, you need not even know these programming terms like ActiveWindow or View.Zoom. Just turn on the Macro Recorder, then manually click View, then Zoom, then set 150 percent. The recorder will watch these steps you take, then write the necessary VBA code that can reproduce those steps. You write no code at all!

- You can write code that performs actions a certain number of times and that makes decisions depending on the situation in which it is running. For example, it could carry out a series of actions on every presentation that's open in PowerPoint.

- You can use VBA to modify the look or behavior of the user interface. VBA can, for example, interact with the user by displaying forms, or custom dialog boxes, that enable the user to make choices and specify settings. You might display a set of formatting options—showing controls such as check boxes and option buttons—that the user can select. Then when the user closes the dialog box, your macro takes appropriate actions based on the user's input.

- You can take actions via VBA that you can't do easily, or at all, when directly manipulating the user interface by hand. For example, when you're working interactively in most applications, you're limited to working with the active file—the active document in Word, the active workbook in Excel, and so on. By using VBA, you can access and manage files that aren't active.

- You can have one application control another application. For example, you can make Word place a table from a Word document into an Excel worksheet.

These tasks, and many more, will be explored throughout this book.

The Difference between Visual Basic and Visual Basic for Applications

VBA is based on Visual Basic, a programming language derived from BASIC. BASIC, created in 1963, stands for Beginner's All-Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code. BASIC is designed to be user-friendly because it employs recognizable English words (or variations on them) rather than the abstruse and incomprehensible programming terms found in languages like C. In addition to its English-like diction, BASIC's designers endeavored to keep its punctuation and syntax as simple and familiar as possible as well.

Visual Basic is visual in that it offers efficient shortcuts such as drag-and-drop programming techniques and many graphical elements.

But in spite of these programmer-friendly features, VB is as powerful and efficient as any other programming language!

Visual Basic for Applications—the variant of VB that we'll be working with in this book—is a version of Visual Basic tailored to manage the Microsoft Office applications.

Each Office application has its own collection of objects (features and behaviors). The set available in each application differs somewhat because no two applications share the exact same features and commands.

For example, some VBA objects available in Word are not available in Excel (and vice versa) because some of Word's tools, like the Table of Contents generator, are not appropriate in Excel.

However, the large set of primary commands, fundamental structure, and core programming techniques of VBA in Word and VBA in Excel are the same. So you'll find that it's often quite easy to translate your knowledge of VBA in Word to VBA in Excel (or indeed to any VBA-enabled application).

For example, you'd use the Save method (a method is essentially an action that can be carried out) to save a file in Excel VBA, Word VBA, or PowerPoint VBA. What differs is the object involved. In Excel VBA, the command would be ActiveWorkbook.Save, whereas in Word VBA it would be ActiveDocument.Save and in PowerPoint it would be ActivePresentation.Save.

VBA always works within a host application (such as Access or Word). With the exception of a few stand-alone programs that are usually best created with Visual Basic .NET, a host application always needs to be open for VBA to run. This means that you can't build stand-alone applications with VBA the way you can with Visual Basic. If you wish, you can hide the host application from the users so that all they see is the interface (typically user forms) that you give to your VBA procedures. By doing this, you can create the illusion of a stand-alone application. But VBA is rarely used for this purpose. If you want to write self-sufficient programs, investigate Visual Basic Express.

What Are Visual Basic .NET and Visual Basic Express?

Visual Basic .NET (VB .NET) is just one version of Microsoft's long history of BASIC language implementations. BASIC contains a vast set of libraries of prewritten code that allow you to do pretty much anything that Windows is capable of. Although VB .NET is generally employed to write stand-alone applications, you can tap into its libraries from within a VBA macro should you need to.

Just remember, each Office application has its own object library, but the .NET libraries themselves contain many additional capabilities (often to manipulate the Windows operating system). So, if you need a capability that you can't find within VBA or an Office application's object library, the resources of the entire .NET library are also available to you.

Visual Basic Express is a free version of VB .NET. After you've worked with VBA in this book, you might want to download and explore Visual Studio Express for Desktop at:

https://www.visualstudio.com/en-us/products/visual-studio-express-vs.aspx

You can use the Community version, or scroll down in the page to locate the Express version.

And if you're interested in manipulating Windows itself, you might want to look at AutoHotKey. It's a powerful resource for those wanting more control over their computer:

Understanding Macro Basics

A macro is a sequence of commands that can be executed at will. That's also exactly the definition of a computer program. Macros, however, are generally short programs—dedicated to a single task. Think of it like this: A normal computer program, such as Photoshop or Chrome, has many capabilities. Chrome can save links to your favorite sites, show you the underlying code of any web page (Ctrl+Shift+I), block websites, display full-screen when you press F11, and so on.

A macro is smaller, dedicated to accomplishing just one of these tasks, such as displaying full-screen. So a macro would likely add one new feature to the huge collection of features already built into an Office application.

In some applications, you can set a macro to run itself automatically. For instance, you might create a macro in Word to automate basic formatting tasks on a type of document you regularly receive incorrectly formatted. As you'll see in Chapter 6, “Working with Variables, Constants, and Enumerations,” in a discussion of the AutoExec feature, you can specify that a macro run automatically upon opening a document of that type.

A macro is a type of subroutine (sometimes also called a subprocedure or function). Generally, people tend to use the shorter, more informal terms sub, procedure, or routine.

As you'll soon see, the Visual Basic Editor starts each of your macros' code with the word Sub. So just note that a macro is a single procedure, whereas a computer program like Photoshop or Word contains a collection of many procedures.

In an Office application that supports the VBA Macro Recorder (Word or Excel), you can create macros in two ways:

- Turn on the Macro Recorder and just perform by hand the sequence of actions you want the macro to perform. Clicks, typing, dragging, dropping—whatever you do is recorded.

- Open the Visual Basic Editor and type the VBA commands into it to write a macro without first recording it.

There's also a useful hybrid approach that combines recording with editing. First record the sequence of actions, and then later, in the Visual Basic Editor, you can view and edit your macro. You could delete any unneeded commands. Or type in new commands. Or use the editor's Toolbox feature to drag and drop user-interface elements (such as message boxes and dialog boxes) into your macro so users can make decisions and choose options for how to run it. Macros are marvelously flexible, and the VBA Editor is famously powerful yet easy to use. This editor is to programming what Word is to writing—a very mature, efficient, and well-designed toolbox.

Once you've created a macro, you specify how you want the user to trigger it. In most applications, you can assign a macro to the Ribbon, to the Quick Access Toolbar, or to a shortcut key combination. This makes it very easy to run the macro by merely clicking an icon or pressing a shortcut key (such as Alt+R). You can also optionally assign your macro to a Quick Access Toolbar button or keyboard shortcut when you first record the macro, via a dialog box that automatically appears when you begin a recording.

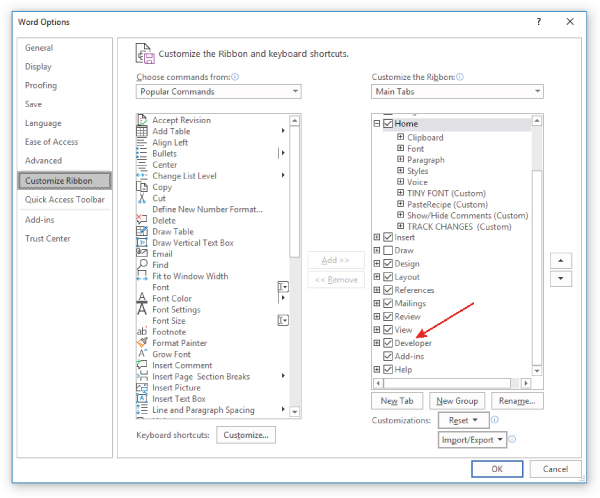

You'll see how all this works shortly. It's simple. (To assign a macro to the Ribbon, first record it, then right-click the Ribbon and choose Customize The Ribbon. Click the Choose Commands From drop-down box, then click the Macros entry to display all your macros.)

Recording a Macro

The easiest way to create VBA code is to record a macro using the Macro Recorder. Only Word and Excel include a Macro Recorder.

You switch on the Macro Recorder, optionally assign a trigger that will later run the macro (a toolbar button or a shortcut key combination), perform the actions you want in the macro, and then switch off the Macro Recorder. As you perform the actions, the Macro Recorder translates them into commands—code—in the VBA programming language.

Once you finish recording the macro, you can view the code in the Visual Basic Editor and modify it if you wish. If the code works perfectly as you recorded it, you never have to look at it—you can just run the macro at any time by clicking the toolbar button or key combination you assigned to the macro.

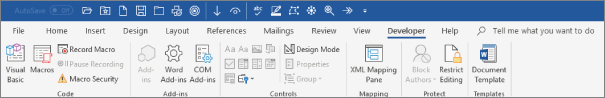

Displaying the Developer Tab on the Ribbon

Before going any further, ensure that the Developer (programmer) tab is visible in your Ribbon. This tab is your gateway to macros, VBA, and the VBA Editor. By default, Microsoft doesn't display this option—so as to avoid confusing non-programmers. (Access and OneNote don't even have this tab. Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Outlook do.) But because you are a programmer, you'll want to add the Developer tab to your Ribbon (see Figure 1.1):

- Click the File tab, then click Options.

They've moved Options way down to the bottom-left of the screen.

- Click Customize Ribbon.

- In the list box on the right, scroll down and click Developer to select it.

- Click the OK button to close the Options dialog box.

Figure 1.1 Click here to add your Developer tab.

You'll now see a new Developer tab to the right of the default tabs on your Ribbon.

In the following sections, you'll look at the stages involved in recording a macro. The process is easy, but you need to be familiar with some background if you haven't recorded macros before. After the general explanations, you'll record example macros in Word and Excel. (Later in the book you'll examine and modify those macros, after you learn how to use the Visual Basic Editor. So please don't delete them.)

Planning the Macro

Before you even start the Macro Recorder, it's sometimes a good idea to do a little planning. Think about what you will do in the macro. In most cases, you can just record a macro and not worry about the context. You can just record it with a document open.

But in some situations you need to ensure that a special context is set up before you start the recording. For example, you might want to create a macro in Word that does some kind of editing, such as italicizing and underlining a word. To do this, you'll want to first have the blinking “insertion” cursor on a word that's not italicized or underlined. You don't want to record the actions of moving the insertion cursor to a particular word. That would make your macro specific to this document, and this word in this document. You usually want a macro to work with more than just one particular document. Your macro is intended to just italicize and underline whatever word is currently under the blinking cursor in any document.

Nevertheless, most simple macros can be recorded without any special planning. Just record whatever you want the macro to do.

Some recorded macros write the code to perform any necessary setup themselves. The setup context will be recorded and made part of the macro. In these cases, you should make sure the application is in the state that the macro expects before you start recording the macro.

For example, if, to do its job, a macro needs a blank active workbook in Excel, the macro itself should create that blank workbook rather than using whichever workbook happens to be active at the time. This saves the user a step when the macro runs. So to do this, start recording before launching a blank active workbook.

Starting the Macro Recorder

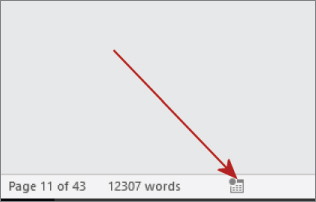

Start the Macro Recorder by clicking the Developer tab on the Ribbon and then clicking the Record Macro button (Figure 1.2). You can also click the Macro Record button on the status bar at the bottom of the application. (With this approach, you don't have to open the Developer tab. Just click the button on the status bar.) It looks like this:

Figure 1.2 Find this Record Macro button on the status bar.

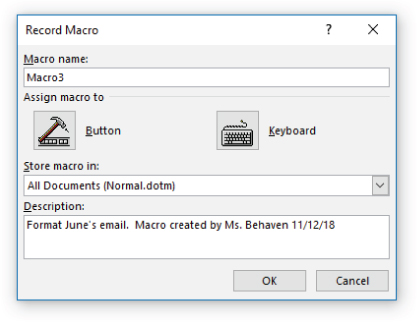

As soon as you start the Macro Recorder, the Record Macro dialog box opens. You see that this new macro has been given a default macro name (Macro1, Macro2, and so on). You can accept that default name or change it. There's also an optional description to fill in if you wish.

To stop the Macro Recorder, you can click the Stop Recording button in the Developer tab. You can alternatively stop the recording by clicking the square black button that appears during recording on the status bar, down on the bottom left of the application's window. (It's the record icon, blackened.)

Once the Recorder is stopped, the square button is replaced with the icon that you can click to start recording a new macro. (In Word for the Mac, click the REC indicator rather than double-clicking it.)

The appearance of the Record Macro dialog box varies somewhat in Word and Excel because the dialog box must offer suitable options to accommodate the varying capabilities particular to each application. In each case, you get to name the macro and add a description of it. In most cases, you can also specify where to save the macro—for example, Word offers two options:

- For global use (making the macro available to all Word documents), store it in the file named

normal.dotm. - If it is merely to be used in the currently active document, choose to store it in a file with the document's name and the

.dotmfilename extension.

An ordinary Word template has a .dotx filename extension, but macros are stored in a file with the filename extension .dotm.

Excel allows you three options: to store macros in the current workbook, or in a new workbook, or for use with all Excel workbooks, in the Personal Macro Workbook. It's the Excel equivalent of Word's Normal.dotm file. (Excel's Personal Macro workbook is saved in a file named Personal.xlsb.) We'll look at this special hidden workbook shortly.

The Record Macro dialog box also lets you specify how you want the macro triggered. Word displays buttons you can click to either open a dialog for entering a shortcut key combination or open the Word Options dialog where you can create a button for this macro that will appear on the Quick Access Toolbar. Excel limits you to Ctrl+ shortcut key combinations as a way of launching macros, so there is no button to display a full keyboard shortcut dialog like the one in Word. Excel has only a small text box where you can enter the key that will be paired with Ctrl as the shortcut.

Most of the Microsoft applications that host VBA have the Developer tab from which you control macro recording, launch the Visual Basic Editor, and otherwise manage macros. Access, however, groups several of its macro-related tools in a Database Tools tab (which is visible by default) and also has a Macro option on its Create tab.

Figure 1.3 shows the Record Macro dialog box for Word with a custom name and description entered. Figure 1.4 shows Word's version of the Developer tab on the Ribbon.

Figure 1.3 In the Record Macro dialog box, enter a name for the macro you're about to record. You can type a concise description in the Description box. This is the Record Macro dialog box for Word.

Figure 1.4 You can use the Developer tab on the Ribbon to work with macros.

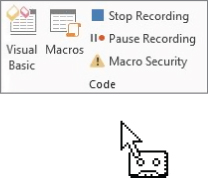

Here's what the primary Visual Basic features on the Ribbon's Developer tab (or Access's Database Tools tab) do:

- Run Macro button Only Access has this Ribbon button. It displays a Run Macro dialog box, in which you can choose the macro to execute (run). Many aspects of VBA in Access are unique only to Access, and Chapter 28, “Understanding the Access Object Model and Key Objects,” covers them in depth.

- Record Macro button Displays the Record Macro dialog box in Word or Excel.

- Macro Security button Displays the Trust Center macro settings dialog. You'll examine this feature in detail in Chapter 19 . This button allows you to specify whether and how you want macros enabled.

- Visual Basic button Switches to the Visual Basic Editor. You'll begin working in the Visual Basic Editor in Chapter 2, “Getting Started with the Visual Basic Editor” (and you'll spend most of the rest of the book employing it).

- Macros button Opens the classic Macros dialog from which you can run, step into (start the Visual Basic Editor in Break mode, more about this in Chapter 3, “Editing Recorded Macros”), edit, create, delete, or open the macro project organizer dialog. (Not all of these options are available in all applications. For example, PowerPoint has no organizer.) Word and Excel have a similar Macros button in the Ribbon's View tab. This button has the ability to open the Macros dialog but can also start recording a macro. Note that Break mode is also referred to as Step mode.

- Add-Ins This is where you can access templates, styles, and specialized code libraries.

- Controls A set of control buttons that, when clicked, insert user-interface components—such as a drop-down list box—into an open document. Similar components can also be added to macros that you create in the VBA Editor. In Chapters 14, “Creating Simple Custom Dialog Boxes,” and 15, “Creating Complex Forms,” we'll explore this user-interface topic.

- Design Mode button Toggles between Design mode and Regular mode. When in Design mode you can add or edit embedded controls in documents. In Regular mode you can interact normally with controls (controls can accept information from the user via typing or mouse clicks).

- Properties button This button is enabled only if you're in Design mode. It allows you to edit the properties of the document (such as removing personal information).

- XML button This section of the Developer tab is explored in Chapters 21 to 24.

- Restrict Editing button Allows you to specify what formatting or editing others are allowed to perform.

- Document Template button Here you can see or modify the current template, or manage add-ins or the global template.

Naming a Macro

Next, enter a name for the new macro in the Macro Name field in the Record Macro dialog box. The name must comply with the following conventions:

- It must start with a letter; after that, it can contain both letters and numbers.

- It can be up to 80 characters long.

- It can contain underscores, which are useful for separating words, such as File_Save.

- It cannot contain spaces, punctuation, or special characters, such as ! or *.

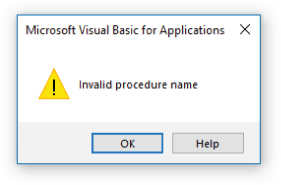

INVALID MACRO NAMES

Word and Excel raise objections to an invalid macro name. If you enter a prohibited macro name in the Record Macro dialog box, these applications let you know—in their own way—as soon as you click the OK button. Word displays a brief, rather cursory message, while Excel gives more helpful info. Figure 1.5 shows how these applications respond to an invalid macro name once it's entered.

Figure 1.5 The dialog boxes supplied by Word and Excel showing invalid macro names.

DESCRIBING YOUR MACROS

Type a description for the macro in the Description text box. Recall that this description is to help you (and anyone you share the macro with) identify the macro and understand when to use it. If the macro runs successfully only under particular conditions, you can note them briefly in the Description text box. For example, if the user must make a selection in the document before running the macro in Word, mention that.

You now need to choose where to store the macro. Your choices with Word and Excel are as follows:

- Word Recall that in Word, if you want to restrict availability of the macro to just the current template (

.dotmfile) or document (.docmfile), choose that template or document from the Store Macro In drop-down list in the Record Macro dialog box shown in Figure 1.2. If you want the macro to be available no matter which template you're working in, make sure the default setting—All Documents (Normal.dotm)—appears in the Store Macro In combo box. (If you're not clear on what Word's templates are and what they do, see the sidebar “Understanding Word'sNormal.dotm,Templates, and Documents” later in this chapter). - Excel In Excel, you can choose to store the macro in This Workbook (the active workbook), a new workbook, or Personal Macro Workbook. The Personal Macro Workbook is a special workbook named

Personal.xlsb. Excel creates this Personal Macro Workbook the first time you choose to store a macro in the Personal Macro Workbook. By keeping your macros and other customizations in the Personal Macro Workbook, you can make them available to any of your procedures. Recall that the Personal Macro Workbook is similar to Word's global macros storage file namedNormal.dotm. If you choose New Workbook, Excel creates a new workbook for you and creates the macro in it.

STORING YOUR MACROS

Word and Excel automatically store recorded macros in a default location in the specified document, template, workbook, or presentation:

- Word Word stores each recorded macro in a module named NewMacros in the selected template or document, so you'll always know where to find a macro after you've recorded it. This can be a bit confusing because there can be multiple NewMacros folders visible in the Project Explorer pane in the Visual Basic Editor. (This happens because there can be more than one project open—such as several documents open simultaneously, each with its own NewMacros folder holding the macros embedded within each document.) Think of NewMacros as merely a holding area for macros—until you move them to another module with a more descriptive name. (Of course, if you create only a handful of macros, you don't need to go to the trouble of creating various special modules to subdivide them into categories. You can just leave everything in a

NewMacrosmodule. As always, how clerical you need to be depends on how organized your mind and memory are. And also on the size of the collection you're dealing with.)If a NewMacros

module doesn't yet exist, the Macro Recorder creates it. Because it receives each macro recorded into its document or template, a NewMacros module can soon grow large if you record many macros. The NewMacros module in the default global template,Normal.dotm, is especially likely to grow bloated, because it receives each macro you record unless you specify another document or template prior to recording. Some people like to clear out the NewMacros module from time to time, putting recorded macros you want to keep into other modules and disposing of any useless or temp recorded macros. I don't have that many macros, so I find no problem simply leaving them within the NewMacros module. - Excel Excel stores each recorded macro for any given session in a new module named

Modulen, where n is the lowest unused number in ascending sequence (Module1,Module2, and so on). Any macros you create in the next session go into a new module with the next available number. So, if you record macros frequently with Excel, you'll most likely need to consolidate (copy and paste) the macros you want to keep so that they're not scattered across many modules.

Choosing How to Run a New Macro

Continuing our exploration of the Record Macro dialog box shown in Figure 1.3, at this point, after you've named the macro, typed a description, and chosen where to store it, it's time to choose how to trigger the macro. In other words, how do you want the user to run the macro: via a shortcut key or via a Quick Access Toolbar button? Good typists generally prefer shortcut keys (they don't have to take their hand off the keyboard to reach for the mouse). But buttons provide at least a visual hint of the macro's purpose. In addition, hovering your mouse on the button also displays the name of the macro.

Shortcut keys and buttons are handy for people who record a moderate number of macros and don't organize them in complex ways—moving them from one module to another. If you create a great number of macros and feel the need to move them into other modules, assigning a shortcut key or button prior to recording becomes less useful. This is because moving a macro from one module to another disconnects any way you've assigned for running the macro.

This limitation means that it makes sense to assign a way of running a macro—prior to recording—only if you're planning to use the macro in its recorded form (as opposed to, say, using part of it to create another macro) and from its module location. If you plan to move the macro or rename it, don't assign a way of running it now. Instead, wait until the macro is in its final form and location, and then assign the means of running it. See “Specifying How to Trigger an Existing Macro,” later in this chapter, for details on how to do this.

Personally, I don't have more than a few dozen macros that I use all the time, so I avoid the complications described in the previous paragraph and this chapter's sidebar titled “Manage Your Macros with Modules.” Instead, I just add shortcut keys when I first create the macro, and leave them all in a single version of Normal.dotm template. However, if you face more complicated situations—such as managing a big set of macros for a company—you might want to manage your macros with modules.

RUNNING A MACRO FROM THE RIBBON

Although it's not available in the Record Macro dialog box, you can add a macro to the Ribbon, like this:

- Right-click anywhere on the Ribbon.

- Click Customize The Ribbon on the context menu that pops out. The Word Options dialog box appears.

- In the Choose Commands From drop-down list, select Macros.

- Click a macro's name to select it in the list.

- Click an existing tab in the list of tabs in the right dialog box where you want to locate your macro.

- Then click the New Group button and specify the name of your custom group.

- Click the Rename button to give your new group a name.

- Click OK to close the Rename dialog box.

- Click the Add button to add your macro.

- Click the Rename button to give your macro an easily understood name, and optionally an icon.

- Click OK to close the Rename dialog box.

- Click OK to close the Word Options dialog box.

RUNNING A MACRO FROM THE QUICK ACCESS TOOLBAR

Here's how to use the Word Options dialog box to assign a macro to a button on the Quick Access Toolbar:

- Right-click anywhere on the Quick Access Toolbar (it's the set of icons in the upper-left corner, normally above the Ribbon), and a menu will appear.

This toolbar will be just below the Ribbon if you've previously selected the Show Quick Access Toolbar Below The Ribbon option from this menu.

- Click Customize Quick Access Toolbar on the menu.

The Word Options dialog box appears.

- In the Choose Commands From drop-down list, select Macros.

- Click a macro's name to select it in the list, as shown in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6 Choose a way to run the macro in Word's Options dialog box. - Click the Add button to insert this macro's name in the Customize Quick Access Toolbar list, as shown in Figure 1.6.

Word adds a button to the toolbar for the macro, giving it the macro's fully qualified name (its location plus its name), such as

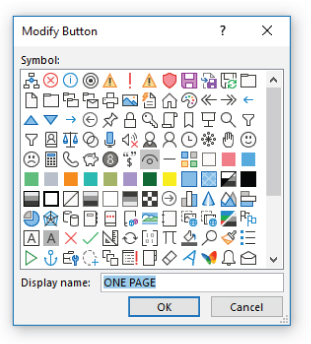

Normal.NewMacros.CreateDailyReport. This name consists of the name of the template or document in which the macro is stored, the name of the module that contains the macro, and the macro's name, respectively. You don't need all this information displayed when you hover your mouse pointer over the button. - To rename the button or menu item, click the Modify button at the bottom of the Customize Quick Access Toolbar list.

Whatever macro is highlighted (currently selected) in the list of toolbar items will be the one you're modifying.

- While you're modifying the macro's name, you might also want to choose a button icon that visually cues you about the macro's purpose (see Figure 1.7). To do that, just double-click whatever icon you want to use, then click OK.

Figure 1.7 Word gives the menu item or toolbar button the full name of the macro. Use this Modify Button dialog to change the name to something shorter and better.

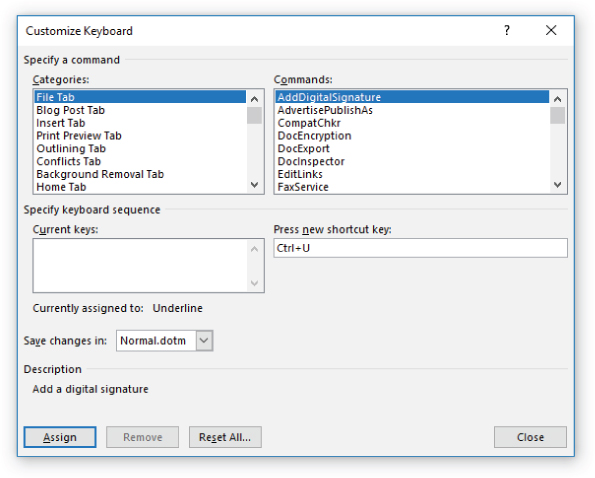

RUNNING A MACRO VIA A SHORTCUT KEY COMBINATION

To assign the macro to a key combination, follow these steps:

- Right-click the Ribbon and choose Customize The Ribbon from the menu that appears.

This opens the Word Options dialog.

- Click the Customize button next to Keyboard Shortcuts in the bottom left of the Word Options dialog box.

- Scroll down the Categories list box until you see Macros, then click Macros to select it.

- Click to select the name of the macro you want to assign a shortcut key combination to.

- Check the Current Keys list box to see if a key combination is already assigned.

If it is, you can press the Backspace key to clear the key combination if you wish, or you can employ multiple key combinations to launch the macro.

- In the Press New Shortcut Key field, type the key combination you want to use to trigger the macro (see Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Set a shortcut key combination for the macro in the Customize Keyboard dialog box. - Check to see if this key combination is already used for another purpose.

If so, you can reassign it, or you can choose a different combination by pressing the Backspace key in the Press New Shortcut Key field.

- Be sure to click the Assign button when you're finished.

Just closing this dialog does not assign the key combination.

A key combination in Word can be any of the following:

- Alt plus either a function key or a regular key not used as a menu-access key.

- Ctrl plus a function key or a regular key.

- Shift plus a function key.

- Ctrl+Alt, Ctrl+Shift, Alt+Shift, or even Ctrl+Alt+Shift plus a regular key or function key. Pressing Ctrl+Alt+Shift and another key tends to be too awkward for practical use.

RUNNING A MACRO THE OLD-FASHIONED WAY

A clumsy, rarely used way to run a macro is to click the Developer tab in the Ribbon. To see how this works, follow these steps:

- Click the Macros icon.

- Click the name of the macro in a displayed list.

- Finally, click the Run button.

By the way, you can also run a macro from within the Visual Basic Editor by pressing F5. This is how you test macros while you're editing them. The macro in which the insertion cursor is located (the blinking vertical line) is the one that will execute when you press F5 in the editor.

ASSIGNING A WAY TO RUN A MACRO IN EXCEL

When you're recording a macro, Excel allows you to assign only a Ctrl shortcut key, not a button, to run it. If you want to assign a Quick Access Toolbar button to the macro, you need to do so after recording the macro (using the Customize feature as described shortly).

To assign a Ctrl shortcut key to run the macro you're recording, follow these steps:

- Start recording the macro to display the Record Macro dialog box, then click the Shortcut Key Ctl+text box to display the blinking insertion cursor.

- Press the shortcut key you want to use. (Press the Shift key at the same time if you want to include Shift in the shortcut.)

- In the Store Macro In drop-down list, specify where you want the Macro Recorder to store the macro. Your choices are as follows:

- This Workbook stores the macro in the active workbook. This option is useful for macros that belong to a particular workbook and do not need to be used elsewhere.

- New Workbook causes Excel to create a new workbook for you and store the macro in it. This option is useful for experimental macros that you'll need to edit before unleashing them on actual work.

- The option Personal Macro Workbook stores the macro in the Personal Macro Workbook, a special workbook named

PERSONAL.XLSB. By keeping your macros and other customizations in the Personal Macro Workbook, they can be made available to any of your procedures. They become global—available to all workbooks. If the Personal Macro Workbook does not exist yet, the Macro Recorder creates it automatically when you choose to store a macro in that option.

- Click the OK button to start recording the macro.

ASSIGNING A WAY TO RUN A MACRO IN POWERPOINT

PowerPoint does not let you record macros, but you can assign a way to run macros written in the Visual Basic Editor, as discussed in the section “Specifying How to Trigger an Existing Macro” later in this chapter.

ASSIGNING A WAY TO RUN A MACRO IN OUTLOOK

Outlook doesn't let you record macros, and by default macros are disabled. To enable macros in Outlook:

- Click the Developer tab on the Ribbon.

- Click the Macro Security icon (it's on the left in the Code section of the Ribbon).

The Trust Center dialog box opens.

- Click the Notification For All Macros option or the Enable All Macros option.

To see how to assign a way to run macros, see the section “Specifying How to Trigger an Existing Macro” later in this chapter.

RECORDING ACTIONS IN A MACRO

When you close the Record Macro dialog box in Word or Excel, the Macro Recorder begins recording the macro. Recall that the Macro Recorder displays the Stop Recording icon (a black square) in the status bar at the bottom left of the screen (and a Stop Recording button in the Developer tab on the Ribbon). In addition, Word displays a small symbol of a cassette tape on the mouse pointer (these tapes were used in the old days, prior to the invention of the CD).

Now you perform the sequence of actions you want to record. What exactly you can do varies from application to application, but in general, you can use the mouse to select items, make choices in dialog boxes, and select defined items in documents (such as cells in spreadsheets). You'll find a number of things that you can't do with the mouse, such as select items within a document window in Word. To select items in a Word document window, you have to use the keyboard (Shift+arrow keys, for example).

Running a Macro

To run a macro you've recorded, you can use four methods to run it within the application:

- If you assigned a Quick Access Toolbar button, use that.

- If you added your macro to the Ribbon, you can use that.

- If you specified a shortcut-key-combination macro, use it.

- A less convenient approach is to

-

- Click Developer ➢ Macros to display the Macros dialog box.

- Select the macro.

- Click the Run button.

Alternatively, you could double-click the macro name in the list box.

The macro runs, performing the actions in the sequence in which you recorded them. For example, suppose you create a macro in Excel that selects cell A2 in the current worksheet, boldfaces that cell, enters the text Yearly Sales, selects cell B2, and enters the number 100000 in it. The Macro Recorder recognizes and saves those five actions. VBA then performs all five actions, step-by-step, each time you run the macro—albeit quite rapidly.

Some applications (such as Word) let you undo most actions executed via VBA after the macro stops running (by pressing Ctrl+Z or clicking the Undo button on the Quick Access Toolbar, undoing one command at a time); other applications do not.

Recording a Sample Word Macro

In this section, you'll record a sample macro in Word. This macro selects the current word, cuts it, moves the insertion point one word to the right, and pastes the word back in. This is a straightforward sequence of actions that you'll work with later in the book, and view and edit in the Visual Basic Editor. (So don't delete this macro.)

Follow these steps to record the macro:

- Create a new document by pressing Ctrl+N.

- Start the Macro Recorder by clicking the Developer tab on the Ribbon, then clicking the Record Macro button. Or click the Macro Record button on the status bar at the bottom of the application. (With this shortcut, you don't have to open the Developer tab. Just click the button on the status bar.)

- In the Macro Name text box, enter

Transpose_Word_Right. - In the Store Macro In drop-down list, make sure All Documents (Normal.dotm) is selected, unless you want to assign the macro to a different template.

This and future examples in this book assume this macro is located in

Normal.dotm, so do store it there. - In the Description box, enter a description for the macro (see Figure 1.8).

Be fairly explicit and enter a description such as Transposes the current word with the word to its right. Created 5/15/19 by Nanci Luz Selest-Gomes.

- Assign a method of running the macro, as described in the previous section, if you want to. Create a toolbar button or assign a keyboard shortcut.

The method or methods you choose is strictly a matter of personal preference. If you'll need to move the macro to a different module (or a different template or document) later, don't assign a method of running the macro at this point.

- Click the OK button to dismiss the Word Options dialog box or the Customize Keyboard dialog box (or just click the OK button to dismiss the Record Macro dialog box if you chose not to assign a way of running the macro).

Now you're ready to record the macro. The Stop Recording option appears on the Ribbon and on the status bar, and the mouse pointer has a cassette-tape icon attached to it.

- As a quick demonstration of how you can pause recording, click the Pause Recording button on the Ribbon.

The cassette-tape icon disappears from the mouse pointer, and the Pause Recording button changes into a Resume Recording button.

- Enter a line of text in the document: The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

- Position the insertion point anywhere in the word quick, and then click the Resume Recording button on the Ribbon to reactivate the macro recorder.

- Record the actions for the macro as follows:

- Use Word's extend selection feature to select the word quick by pressing the F8 key twice.

- Press the Esc key to cancel Extend mode.

- Press Shift+Delete to cut the selected word to the Clipboard. The insertion point is now at the beginning of the word brown.

- Press Ctrl+right arrow to move the insertion point right by one word so that it's at the beginning of the word dog.

- Press Shift+Insert or Ctrl+V to paste in the cut word from the Clipboard.

- Press Ctrl+left arrow to move the insertion point one word to the left.

This restores the cursor to its original position.

- Click the Stop Recording button on the Ribbon or status bar.

Your sentence now reads, “The brown quick fox jumped over the lazy dog.”

You can now run this macro by using the toolbar button or keyboard shortcut that you assigned (if you chose to assign one). Alternatively, click the Macros button in the Developer tab and run the macro from the Macros dialog box.

At this point, Word has stored the macro in Normal.dot. If you don't save macros until you exit Word (or until an automated backup takes place), Word doesn't, by default, prompt you to save them then. It just saves them automatically. But it's best to click the Save button in the File tab to store Normal.dot now. That way, if Word or Windows crashes, you will avoid losing the macro.

Recording a Sample Excel Macro

In the following sections, you'll record a sample Excel macro. This macro creates a new workbook, enters a sequence of months into it, and then saves it. You'll work with this macro again in Chapter 3, so please don't delete it.

Create a Personal Macro Workbook If You Don't Have One Yet

If you don't already have a Personal Macro Workbook in Excel, you'll need to create one before you create this procedure. (If you do have a Personal Macro Workbook already, skip to the next section.) Follow these steps:

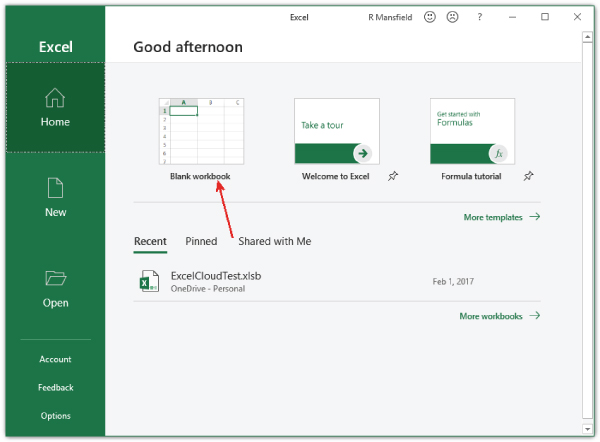

- Start Excel and click the blank workbook so you can see the Ribbon (see Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9 Clicking the blank workbook - Click the Developer tab in the Ribbon, then click the Record Macro button on the Ribbon (or just click the Record Macro button down below on the status bar) to display the Record Macro dialog box.

If the Developer tab isn't visible, follow the instructions earlier in this chapter in the section titled “Displaying the Developer Tab on the Ribbon.” If the macro options such as the Record Macro button are disabled—gray and can't be clicked—then follow the instructions earlier in this chapter in the sidebar titled “A Warning about Security.”

- Accept the default name for the macro because you'll be deleting it momentarily.

We're just creating the Personal Macro workbook at this point.

- In the Store Macro In drop-down list, choose Personal Macro workbook.

- Click the OK button to close the Record Macro dialog box and start recording the macro.

- Type a single character in whichever cell is active, and press the Enter key.

- Click the Stop Recording button on the Ribbon or status bar to stop recording the macro.

- Click the Unhide button on the View tab to display the Unhide dialog box.

- Select PERSONAL.XLSB and click the OK button.

- Click the Developer tab in the Ribbon, then click the Macros button on the Ribbon to display the Macros dialog box.

- Select the macro you recorded and click the Delete button to delete it.

- Click the Yes button in the confirmation message box.

You now have caused Excel to generate a Personal Macro Workbook that you can use from now on to hold your global macros.

Record the Macro

Now, to create a practice macro, start Excel and follow these steps:

- Create a new workbook by choosing File ➢ New ➢ Blank Workbook.

- Click the Developer tab in the Ribbon, then click the Record Macro button on the Ribbon (or just click the Record Macro button on the status bar at the bottom).

This displays the Record Macro dialog box, shown in Figure 1.3, with information entered.

- Enter the name for the macro in the Macro Name text box:

Add_Months. - In the Shortcut Key text box, enter a shortcut key if you want to.

Remember that you can always change the shortcut key later, so you're not forced to enter one at this point.

- In the Store Macro In drop-down list, choose whether to store the macro in your Personal Macro Workbook, in a new workbook, or in this active workbook.

As discussed a little earlier in this chapter, storing the macro in the Personal Macro Workbook gives you the most flexibility because it is Excel's global macro container. For this example, don't store the macro in the active workbook. Instead, store it in your Personal Macro Workbook. Remember, we'll use this macro in future examples later in this book.

- Type a description for the macro in the Description text box.

- Click the OK button to dismiss the Record Macro dialog box and start recording the macro.

When Excel starts running it sometimes randomly doesn't open the Personal Macro Workbook. So if you see an error message telling you that your “Personal Macro Workbook in the startup folder must stay open for recording,” you'll need to open it by hand. If it's necessary to do that, follow these steps:

- Close the Record Macro dialog box.

- Choose File ➢ Options ➢ Trust Center.

- Click the Trust Center Settings button.

- Click Trusted Locations in the left pane.

- Click to select “Excel default location: User StartUp” then look down to where it says Path and you'll find the location you want on the hard drive.

It should resemble this:

C:UsersYournameAppDataRoamingMicrosoftExcelXLSTART.

Use File Explorer to find this path, then double-click the PERSONAL.XLSB file to open it.

- Continue on to step 8.

- Click cell A1 to select it.

It may already be selected; click it anyway because you need to record this click instruction.

- Enter January 2019 and press the right arrow key to select cell B1.

Excel automatically changes the date to your default date format. That's fine.

- Enter February 2019 and press the left arrow key to select cell A1 again.

- Drag your mouse from cell A1 to cell B1 so that those two cells are selected.

- Drag the fill handle from cell B1 to cell L1 so that Excel's AutoFill feature enters the months March 2019 through December 2019 in the cells.

The fill handle is the small black dot in the lower-right corner of the selection frame. You'll know you're on it when the cursor changes from a white to a black cross.

- Click the Stop Recording button on the Ribbon.

It's on the left side of the Developer tab—in the Code section.

Now let's test our new macro:

- Create a new workbook by choosing File ➢ New ➢ Blank Workbook.

- On the Developer tab, click the Macros button to open the Macro dialog box.

- Double-click PERSONAL.XLSB!Add_Months.

You should now be able to see the months filled into the new workbook.

Go ahead and delete the two workbooks you created in this session. They're no longer needed. Just click the X in the upper-right corner to close them, then choose Don't Save. But do save the PERSONAL.XLST workbook. You'll see a message asking if you want to save the changes you made to the Personal Macro Workbook. Click Save All.

Specifying How to Trigger an Existing Macro

If you didn't assign a way of running the macro when you recorded it, you can do that now as described here.

Assigning a Macro to a Quick Access Toolbar Button in Word

To assign a macro to the Quick Access Toolbar, follow these steps:

- Right-click anywhere on the Quick Access Toolbar (it's the set of icons in the upper-left corner, by default above the Ribbon). A menu appears.

- Click Customize Quick Access Toolbar on the menu. The Word Options dialog box appears.

- In the Choose Commands From drop-down list, select Macros.

- Click the name of the macro you want to assign a button to.

- Click the Add button to copy the macro name into the list of buttons on the right.

- Click the Modify button if you want to assign a different icon or modify the button's name.

- Click OK to close the dialog.

Assigning a Macro to a Shortcut Key Combination

The section “Running a Macro via a Shortcut Key Combination,” earlier in this chapter, explained how to do this in Word. PowerPoint and Access do not let you assign a macro to a key combination. Excel uses a slightly different approach than Word, limiting you to Ctrl and Shift combinations, as described earlier in this chapter in the section “Assigning a Way to Run a Macro in Excel.”

Deleting a Macro

To delete a macro you no longer need, follow these steps:

- Click Developer ➢ Macros to display the Macros dialog box.

- Choose the macro in the Macro Name list box.

- Click the Delete button.

- In the warning message box that appears, click the Yes button.

- Click the Close button or the Cancel button to close the Macros dialog box.

Or, you can just

- Locate the macro in your VBA editor.

- Highlight it, and press the Del key to remove it.

- Click the Developer tab, and then on the far left, click the Visual Basic icon to open the editor.

The Bottom Line

- Record a macro. The easiest way to create a macro is to simply record it. Whatever you type or click—all your behaviors—are translated into VBA automatically and saved as a macro.

- Master It Turn on the macro recorder in Word and create a macro that moves the insertion cursor up three lines. Then turn off the macro recorder and test the new macro.

- Assign a macro to a button or keyboard shortcut. You can trigger a macro using three convenient methods: clicking an entry on the Ribbon, clicking a button in the Quick Access Toolbar, or using a keyboard shortcut. You are responsible for assigning a macro to any or all of these methods.

- Master It Assign an existing macro to a new Quick Access Toolbar button.

- Run a macro. Macros are most efficiently triggered via a Ribbon entry, or by clicking a button on the Quick Access Toolbar, or by pressing a shortcut key combination such as Alt+N or Ctrl+Alt+F. When you begin recording a macro, the Record Macro dialog has buttons that allow you to assign the new macro to a shortcut key or toolbar button. However, if you are using the Visual Basic Editor, you can run a macro by simply pressing F5.

- Master It Execute a macro from within the Visual Basic Editor.

- Delete a macro. It's useful to keep your collection of macros current and manageable. If you no longer need a macro, remove it. Macros can be directly deleted from the Visual Basic Editor or by clicking the Delete button in the Macros dialog (opened by choosing Developer ➢ Macros).

- Master It Temporarily remove a macro, then restore it, using the Visual Basic Editor.