Closeout for Single and Multiple Projects

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

• Explain the reasons closing out projects and phases is a valuable and necessary part of the management of single and multiple projects.

• Describe the elements of a closing process in the areas of transition, administrative closure, and salvage.

• Provide rewards and praise for project team members.

• Conduct a Lessons Learned process and recover value from the project for future projects.

• Recognize and avoid typical problems in closing a project.

• Develop a closeout checklist for single and multiple projects.

Estimated timing for this chapter:

| Reading | 40 minutes |

| Exercises | 60 minutes |

| Review Questions | 10 minutes |

| Total Time | 1 hour 50 minutes |

CLOSING TIME

Project closeout is the final phase of project management, in which you bring the project to a close, deliver the deliverables, ensure customer satisfaction, and do the administrative activities necessary to wind down the operation.

You don’t merely close out a project, you also close out each phase of a long project. Why close out a phase? Let’s imagine you’re bringing a new computer to market. The first phase may be a competition among different ideas for the new computer. The end of the phase is the decision on which way to go. The project changes its nature at the end of a phase. You may not need or want the same team going forward; different skills and processes are required. The same thing will be true of the design phase, the manufacturing phase, the marketing and distribution phase, and the maintenance phase.

When you’re managing multiple projects, you’ll close out each individual project at least once, depending on the number of phases. If your collection of projects is also a project in its own right, you’ll close out the overall project as well.

Although closeout seems fairly straightforward, it’s more complex — and much more important — than it may appear on first glance. In this chapter, you’ll learn not merely how to close out projects, but also why it’s vital to your success.

CLOSING PROCESSES

To finish a project, you have to finish and deliver its output (product or service) to the customer, doing whatever installation, transition, training, or operation is necessary to hand off the work. Not officially separate, but requiring a whole new world of attention, is the process of obtaining customer approvals, verifying deliverables, and ensuring overall satisfaction with the job. That can vary from being simple and straightforward to being a highly complex negotiation.

You must perform the technical and operational tasks necessary to deliver project outputs and shut down the work. Contract closeout is an important step on any project that has used contracts, either by issuing contracts to others, or in many cases, performing the project as a contractor. Depending on your organization’s policies, contract closeout can involve numerous steps, including verification, completing forms, negotiating exceptions and change orders, final invoicing, and approving invoices.

There may be ongoing operational work that results from your project. If you’re an IT department that’s just implemented the well-known business software system known as SAP, for example, the project has ended, but operational responsibility for running and maintaining the software remains. You need a transition plan to ensure this takes place properly.

It’s also time to extract value and opportunity from the project. Good project managers prepare Lessons Learned files, examine the project for information and resources that can be reused, and capture project metrics to improve future estimating and to power internal improvement efforts.

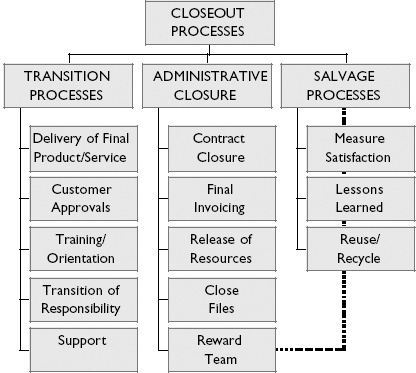

Exhibit 11-1 shows the activities in the closeout process. Not all projects require all the activities shown, nor do they require that each activity be performed with equal depth and rigor.

xhibit 11-1

Closeout Processes

TRANSITION PROCESSES

Finishing the project work doesn’t automatically mean finishing the project. The output of the project — the product or service you have developed — has to be transferred to the next owner in the process. That new owner may be an external customer or it may be some function inside your own organization. It can even be you, if you’re the primary user or beneficiary of the product or service. No matter who it is, there’s almost always work involved in turning it over.

Deliver the Final Product or Service

Who gets the product or service? Where does the product or service need to be? How will you get it there? Do you have to install or adjust what you’ve done at that location? What are all the pieces and components you need to provide? Is there documentation to go with it? Are you responsible for packaging and shipping? Does shipping time count against your deadline?

The time to ask most of these questions is early in the project. Remember that each deliverable takes a minimum of one work package to accomplish. You need to be able to draw a clear linkage between each deliverable and the work package where it is created.

Transition itself adds deliverables to the project: if you have to build an insulated shipping container, contract a trucking company, and buy insurance for the shipment, these are project activities that take time and cost money.

Obtain Customer Approvals

Who decides whether the product or service is satisfactory? Whose signature is necessary? How will the customer evaluate the work we’ve done? Is the evaluation based on objective or subjective criteria? What documents, forms, or contracts do we need?

As with most aspects of project management, whether single or multiple, make sure you define the necessary actions well in advance; you don’t want to be in the situation of trying to figure out who needs to accept it when you’re trying to finish up.

Provide Training and Orientation for Users and Operators

What training, orientation, or familiarization do you need to provide owners, users, operators, and consumers of the product or service? At a minimum, you normally need to provide a walk-around with the new owners to familiarize them with the operation or maintenance of the product or service. In some cases, training turns into a project all its own.

Transition Responsibility for Operation and Maintenance

What parts of the operation and maintenance of the product or service will belong to the customer or user? What parts will remain the responsibility of your organization? At what point do these responsibilities move from the project management team to someone else?

If the new product you just ordered is damaged in shipping, your claim is often against the shipper, not the original manufacturer. That’s an example of the transitioning of responsibility for operation and maintenance. If it’s working when it leaves the manufacturer, the manufacturer has delivered as promised.

In planning for closeout, consider issues of transition. When does your responsibility end and someone else’s begin? Don’t leave these issues to chance or to later interpretation.

Establish Support Systems and Provide Support

After the project is over, are you completely done with the product or service, or will you have an ongoing support relationship with it? Will you provide any sort of warranty or guarantee? If the product or service fails in operation, to what extent are you responsible or liable? Is maintenance and support a potential profit center? If you are doing the project for internal use, are you also the operator and maintainer (common in IT development)?

Even if the project is complete, your involvement with the product or service may not be. This is not necessarily a bad thing: you can make a lot of money in maintenance and support. As with most other closeout concerns, what’s important is to spell out these issues clearly and in advance of need so that you avoid confusion and error.

Think About It …

What transition closeout issues are you likely to encounter on your projects? How can you plan, control, and gain maximum benefit from the transition process?

ADMINISTRATIVE CLOSURE

Administrative closure is internal to the organization. It’s what you and your team must do so that your own organization considers the project to be finished. Because the organization’s policies tend to remain relatively constant over time, you have the opportunity to standardize some of these processes, or they may already exist in a standardized form. If you’re not aware of your organizational procedures in this area, or if they haven’t been sufficiently developed, getting this under control is another aspect of planning for a successful project.

Close Out Contracts

If your project has involved procurement or contracting activities, you have to close these out with your contracting office. At a minimum, the contracting office needs to know that any supplies or services you purchased were in fact delivered, that there are no outstanding issues or claims, and that necessary paperwork has been provided. Invoices have to be received in order to be paid.

Contract documentation needs to be archived in case of future issues. Sometimes there are additional requirements, such as obtaining workman’s lien releases on a construction project.

Submit Final Invoices

Your customer has to pay the invoice, but is not usually obligated to pay invoices never submitted. Often, one of the most essential parts of the job from your organization’s point of view is to submit the necessary invoices and documentation to customers. In some cases, you may receive a series of partial payments, especially on a longer-term project; in this case, you have to invoice periodically throughout the project.

Even if the project is completely internal to the organization, there are still payment issues: billing and timesheet allocation for internal staff, updated information for the accounting department, and other processes the organization uses to ensure that information on your spending gets picked up in the overall financials.

Release Project Resources for Other Work

During the project, you tend to accumulate resources: people who temporarily support the project work, tools and equipment, and other things that have value beyond your own project. It’s commonly a responsibility of the individual project manager to make sure the job site is cleaned up and resources returned to the organization for future use. As a manager of multiple projects, this becomes a key focus area for you as well: the person most in need of those project resources is usually you.

Close Project Files and Finalize Internal Administrative Procedures

The project file not only allows you to archive critical project information, but also helps you with the next step, which is analyzing the project for Lessons Learned. Some of this information needs to be part of the company’s formal and legal archives, but other information may be stored more informally.

Check with your legal department on organizational policies about saving and discarding information, especially contractual information. Make sure you comply with all those policies. In general, saving project information is a good tool, because it provides you with an increasingly valuable base from which to develop estimates and risks for future projects.

Because full and proper archiving takes significant amounts of time and focus, it may be difficult to do it well. If you’ve maintained project files and a project binder throughout the process, archiving the project may simply involve a review of materials and moving them from the active part of your files to the storage portion.

Celebrate Success and Reward Team Members

Your success is ultimately given to you by the work and achievement of other people. It’s appropriate for you as the project manager to accept some of the credit, because you would have had to accept all the blame. Honor and good policy demand, however, that you share that credit. Besides the dictates of simple good behavior, there are a number of practical payoffs you receive when you celebrate the work and achievement of your team and of the individuals on your team.

If you ask people what they’d most like to have as a reward for outstanding performance, the overwhelming chorus is usually “money!” And money is certainly one way to reward good performance. But the project manager is often not the supervisor of all team members, and you may not have the opportunity or the power to give people financial rewards. You can recommend them for financial rewards if your organization provides them, and that’s usually worth the effort, but money is frequently not an option.

Recognize that people often work more for self-esteem and self-actualization than for physical or material rewards. A sincere thank-you note (copies for the personnel file and for the supervisor of record or other appropriate senior managers) or some personal memento of the project experience has a surprisingly positive effect. The key is sincerity—if it’s clear you mean it, people will like it. If they don’t think you mean it, they’ll still take it (especially if it’s money) but it won’t particularly improve performance.

People can find enormous satisfaction in project work, because at the end they have something to show for their effort. The best kind of celebration is something that reminds them of that effort and applauds their performance in achieving it.

To celebrate the building of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, all staff received a little certificate of thanks, each hand-signed by the director. Down at the bottom was a tiny little souvenir: a one-inch square of silver fabric (complete with dry rot) taken from the restoration of the Spirit of St. Louis. The cash value was insignificant, but the celebration and reminder of achievement was very real indeed.

Your souvenir may not be something with historical significance, but that’s not what you need. Thoughtfulness, creativity, and a sense of shared achievement are what make tokens of recognition real and significant, and that’s something within all our grasps.

Notice the “dotted line” relationship in Exhibit 11-1 showing that rewarding the project team is also one of the closeout “salvage” processes, described in the following section. A team that feels appreciated and rewarded is ready for a new project. As a manager of multiple projects, you should remember that praising people isn’t merely part of the end of the current project, but is equally part of teeing up the next project.

Think About It …

What issues of administrative closure are you likely to encounter? What is the process for releasing people to additional work? What is the best way to reward and motivate your team at project’s end?

SALVAGE PROCESSES

In the same way that rewarding people for performance on the previous project may improve motivation and behavior on the next project, there are a variety of closeout activities that benefit future projects or the organization as a whole. We call these salvage processes, because they turn the leftover bits of the project into resources you can use later.

Measure and Ensure Customer Satisfaction

An unhappy customer isn’t just a sign of a problem with the current project, it’s a potential loss for the organization as a whole — and sometimes a personal loss for you as a manager of multiple projects. Consider the following research about customers from the Technical Assistance Research Programs (TARP):

• The average business doesn’t hear from 96% of unhappy customers.

• For every single complaint received, 26 people have unvoiced problems, six of which are serious.

• Of those who do not complain, 90% will not buy again or come back.

• Of those who do complain, as many as 70% will do business with you again if their complaint is resolved; 95% will return if their complaint is resolved quickly.

• The average customer with a complaint tells 9-10 people; 13% of complaining customers tell more than 20 people — and the number may not include you!

• People whose complaints are resolved tell an average of five people.

Source: http://www.rctaylor.com/Images/The_Price_of_a_Dissatisified_Customer.pdf. Referenced November 11, 2010.

Customer satisfaction metrics benchmark how well you did, but customer satisfaction isn’t something you leave to chance. Your job is to make sure you receive high marks in this area: customers need to be managed as well as served.

Perform a “Lessons Learned” Review

We strongly recommend that you make a formal project evaluation process a fundamental step in any project. There are enormous potential benefits to be gained from relatively minor effort. After all, every project, whether successful or not, demands substantial concentration and focus, creativity in problem solving, and a wide range of practical skills. Unfortunately, unless a specific effort is made to ensure the knowledge and experience learned on one project carries forward, much of the value is lost as the team turns to the next project in line.

It’s important to distinguish a Lessons Learned program from its evil twin cousin, “blamestorming”—the creative process of figuring out who will be the scapegoat for this project. In both activities, you spend time figuring out what went wrong and how it happened. In the second, once you’ve assigned guilt, the exercise is over. But in the first, the goal is not blame or faultfinding. For every mistake that was made by a specific individual on the team, there are usually several other people who could easily have made the same mistake. If all of us understand the mistake and know what to do in the future to avoid it, then we all profit.

Organize a Lessons Learned meeting and circulate a list of discussion questions as the agenda before the meeting. Exhibit 11-2 provides a list of sample questions with which to start. Encourage free and open discussion and try to keep it positive. If people are primarily concerned with avoiding blame, little value will result.

Complete your project by developing a Lessons Learned document in the form of a report. Exhibit 11-3 provides an outline you can use. To the extent that any part of the document is a discussion of project mistakes, avoid naming names. Even if your intent is not to cast blame, finding one’s name in print associated with an error is not comforting to most people. Focus on the future. How will the next project or projects run better, more smoothly, with fewer errors, with higher quality, and with more accurate cost and schedule performance? Start this as an organizational tradition, and watch all the projects in the organization improve!

xhibit 11-2

Sample Questions for Lessons Learned Sessions

• What did we do right?

• What things surprised us on this project that weren’t in our plan?

• Where could we improve?

• What mistakes did we make?

• What should we experiment with on our next project?

• What did we learn by doing this project?

• What could we automate or simplify that we do over and over again?

• What other value could we extract from the project we just completed?

• What skills do we anticipate we need to improve our project performance?

• How well did we perform the project management process? How did it help us?

• If there was one thing we could do over again, what would it be?

• What’s one good thing each team member did that helped the project?

• How does the customer feel about how we performed and the quality of the result?

Identify Opportunities to Reuse and Recycle

A 3M scientist, Dr. Spencer Silver, accidentally developed a “low-tack” adhesive in 1968, but nobody could figure out anything useful to do with it. In 1974 a colleague, Art Fry, used the adhesive to anchor bookmarks in his hymnal, but in 1977, a market test of the concept failed. 3M tried again a year later, with a massive free samples campaign, and by 1980 Post-it® notes were a major product line.

Projects often create significant incidental value, but a lot of that value doesn’t pay off unless it’s recognized and exploited. Looking for value in unexpected places can pay great dividends. Sometimes even failed projects yield value. If Pisa’s tower didn’t lean, who would visit it?

Exhibit 11-4 lists potential sources of resources and opportunity for future projects.

xhibit 11-3

Outline for a Lessons Learned Report

1. Introduction

a. Purpose and objectives of the Lessons Learned report

b. Summary of recommendations for continuous improvement

2. Description of the Project

a. Summary of original goals and objectives, purpose of the project

b. Timeline of the project from initiation to closeout, summary of major milestones and components

c. Overall evaluation of the project outcome

i. How did the project outcome affect our business and the customer’s business?

ii. Did it meet time, cost, and performance goals?

3. Evaluation and Assessment Process

a. Technical evaluation of performance information

b. Financial analysis of the project

c. Interviews, brainstorming sessions, and surveys

4. Key Lessons Learned Questions

a. What did we do right?

b. Where could we improve?

c. What surprises did we encounter?

i. Should we expect these surprises to recur?

ii. How did they affect the project?

d. What did we learn or accomplish on this project that will help us on future projects?

5. Recommendations and Suggestions for Future Improvement

xhibit 11-4

Finding Resources and Opportunity for Future Projects

• What processes or tools did we develop in the course of this project that might be used again?

• What value can be extracted from things we tried that weren’t successful?

• What parts of our plan for the current project can be used as a template for future projects?

• If we had had perfect knowledge, what might we have done differently? Should any of those things be part of how we run the next project?

Think About It …

What salvage process issues are you likely to encounter on the project? How will you gain maximum value for future projects?

TYPICAL PROBLEMS IN CLOSING A PROJECT

Problems in closing out a project fit into two overall categories:

• Problems that arise in the process of closeout

• Problems that have been ignored or missed in earlier stages of the project

Project closeout is everyone’s final opportunity to ensure that the project delivers what it should. Any unmet needs are brought onto the table now. Some problems that arise during closeout are not necessarily leftovers from unresolved problems, however. These include:

• Problems with customer acceptance. Customer needs can mutate on short notice. Even if you’ve kept close ties with your customer throughout the project, last-minute changes can throw project completion for a loop. Although a last-minute surprise may not always be avoidable, even a little advance notice beats none at all. If you haven’t solved a problem yet, the second-best thing is to have a plan for solving it.

• Unexpected staff turnover. When a project nears its end, most of the technical work is done, and the pace of work tends to slow somewhat. At the same time, in most organizations, other projects are ramping up and need staff. The desire of your technical performers to seek new work and the need of other project managers for trained staff combine to make an irresistible force to raid your staff.

• Missing documentation. The ability to do the work and the ability to keep good records of the work done aren’t particularly compatible. Documentation is often thought of as a last-minute activity that can be done in a halfhearted way, and there may be a scramble at the end of the project to get it done.

• Missing administrative deliverables. Your organization and your customer’s organization normally have administrative requirements for projects, including processing of sign-offs and approvals, completion of forms and paperwork, and delivery of resource and dollar use information to appropriate managers. It’s often the case that not all the mandatory administrative requirements are listed in a single place. Just when you think you’re finally complete with the project, you discover an entire new set of activities to be performed!

• Surprises in transition management. The transition from building something to using something, from designing something to manufacturing something, is fraught with challenges. From training to the inevitable small adjustments, from preparing documentation to overseeing the migration from old systems to new, this area requires careful planning and execution.

• Rumors. On large multiyear projects, people begin to worry whether they’ll have a home after the project is complete. Sometimes this worry is justified. If you know there will be some layoffs or terminations at the end of the project, you need to prepare for them. If, on the other hand, people will have continued employment, make sure they know about it, or else you’ll have people jumping ship prematurely.

CHECKLISTS AND PLANNING FOR CLOSEOUT

As with other stages in the project life cycle, begin thinking about closeout during the planning phase. What will have to be done in order for the project to be considered completely finished? Who will do these various tasks? How long will it take?

Especially in a multiple project environment, it’s highly desirable to standardize closeout planning. The first rule is to insist that every project plan have at least one WBS work package for closeout activities so that time and resources are available to get them done.

Another popular tool is to develop a closeout checklist, customized for the administrative and policy requirements of your organization and program. The form in Exhibit 11-5 is a standard U.S. Department of Defense closeout checklist.

xhibit 11-5

Closeout Checklist

Obtained from http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/infomgt/forms/eforms/dd1597.pdf on 11 November 2010.

CLOSING OUT IN THE MULTIPLE PROJECT ENVIRONMENT

If you’re managing multiple projects, proper closeout is the only way to get projects off your plate, and a proper Lessons Learned report is the best way to improve outcomes and lower costs on future projects. Take the time to standardize the templates, outlines, and processes you use in closing out and learning from projects.

Project closeout is the final phase of project management, in which you finish the work, deliver the output, ensure customer satisfaction, perform administrative tasks, and extract value that can be used in future projects or otherwise to benefit the organization.

You not only close out a project, but also each phase of a project. In managing multiple projects, standardizing closeout is highly desirable because you will be doing a lot of it.

Closeout processes fit into three categories: transition processes, administrative closure, and salvage processes. The best opportunity to have a smooth closeout is to plan for closeout early in the project. Standardize closeout processes across multiple projects when possible. Some closeout processes benefit future projects rather than the current one. Lessons Learned, rewarding the team, and salvaging value are bonus ways to extract extra benefit from the projects you do.

Review Questions

|

1. The activities of obtaining customer approval, providing training and orientation, and delivery are called: (a) administrative closure. (b) transition processes. (c) salvage processes. (d) release of resources. |

1. (b) |

|

2. It is important to close out phases as well as entire projects because: (a) each phase requires documentation for Federal tax purposes. (b) the customer needs to be part of every phase transition. (c) budgetary records must be updated on a regular basis. (d) at the end of each phase, the project often changes its nature. |

2. (d) |

|

3. Incidental value in a project refers to: (a) the “Lessons Learned” process of identifying key incidents. (b) money spent above and beyond the authorized budget. (c) things developed during the course of the project that can be reused or recycled for further benefit. (d) a project that involves a small amount of money compared to other projects. |

3. (c) |

|

4. To recognize members of the project team, a good project manager should always: (a) provide a cash incentive for excellent performance. (b) take into account that people often work more for self-esteem and self-actualization than for physical or material rewards. (c) provide a tangible souvenir of the project. (d) prepare a performance evaluation for each team member. |

4. (b) |

|

5. A proper “Lessons Learned” process involves: (a) determining who is at fault for each mistake. (b) an external review of the project by senior management. (c) achieving a blame-free understanding of project events for use in the future. (d) completing a closeout checklist. |

5. (c) |