CHAPTER 6

General Discussion and Conclusions

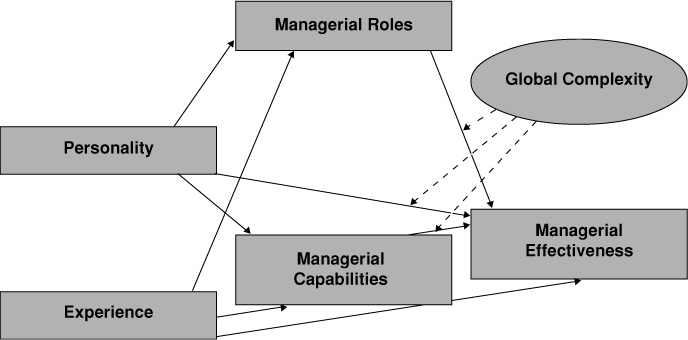

This report presents a conceptual model designed to help identify what it takes to be an effective global manager. The model is based on the literature and our experience working with international executives. With this research we have been able to help answer questions about roles, characteristics, traits, and experiences of effective global managers.

Returning to our conceptual model (see Figure 1 on p. 3), the antecedent variable personality does help to explain the kinds of managerial capabilities and role behaviors a manager is most likely to acquire. Personality is also associated with managerial effectiveness as predicted. Personality was not, however, related to a manager’s previous work experience. Therefore, we have modified the model, as reflected in Figure 6 (p. 62), to reflect this change.

Experience, the other antecedent variable, was not a predictor of effectiveness. Its inclusion in the model, however, turned out to be more fruitful than we had anticipated. Our results revealed a paradox for managers who aspire to be global leaders. On one hand, exposure to other cultures is probably critical for developing the skills needed for global roles. Just as the personality variables share variance with many of the critical global skills, suggesting a link between traits and skill acquisition, a primarily post hoc review of the relationship between cosmopolitan experiences reveals a link between experience and skill set (see Appendices C and D). On the other hand, managers with these experiences were rated lower in some cases by their bosses on the interpersonal criterion measure (this phenomenon will be discussed more fully later in this section).

The remaining variables in the model, managerial capabilities and managerial roles, were in one form or another associated with managerial effectiveness as predicted.

We suggest that the revised model provides a useful heuristic to identify, appreciate, and explain the relationships among traits, experiences, skills, and capabilities needed to be an effective manager in a global role. These results show that as complexity accrues from the manager’s simultaneously juggling time zones, country infrastructures, and cultural expectations, there is a shift in the skills, capacities, traits, and experiences needed for managerial effectiveness. We now turn our attention to the research questions for which the model was constructed.

What Do Global Managers Do?

The global executives we studied placed great importance on the roles of liaison (networking across organizational boundaries) and spokesperson, suggesting that as work responsibility shifts from domestic to global, managers place greater emphasis on external roles that take place at the organization’s periphery. Our global manager subjects also rated the managerial capabilities of cultural adaptability, international business knowledge, and time management as more important to their job than did local managers. These results track with our definition of a global manager—one who manages and leads across distance, borders, and cultural expectations. An intriguing outcome, worthy of further investigation, is that the roles and capabilities identified by global managers as most important to their work—liaison, spokesperson, and time management—were not the roles and capabilities that their bosses identified as significant to managerial effectiveness.

What Does It Take for a Manager to Be Effective when the Work Is Global in Scope?

The patterns of traits, role skills, and capabilities global managers need to be effective is similar to that of domestic managers. The bosses of global managers say emotional stability, skill in the roles of leader and decision maker, and the ability to cope with stress are key components to managerial effectiveness regardless of the job’s global complexity. In addition, bosses look to conscientiousness, skill in the role of negotiator and innovator, business knowledge, international business knowledge, cultural adaptability, and the ability to take the perspective of others as significant to the effectiveness of global managers.

In regard to how personality relates to managerial effectiveness, emotional stability occupies an important place. It appears that the action roles (decision maker and negotiator) are relatively more critical to the global manager than to the domestic manager. The learning capabilities were also significantly more critical to effectiveness ratings for the global manager.

While these results may be intuitively satisfying, it is somewhat surprising that conscientiousness and business knowledge were not significantly related to effectiveness ratings for the domestic managers. (It’s important to note, however, that all of these results could be an artifact of this particular sample.)

As for the relationship between experience and effectiveness, many of the results did not support our conjectures. Neither early exposure to other languages and cultures, experience living in other countries, multilingualism at work, nor past experience working with heterogeneous workgroups predicted effectiveness ratings in a global or domestic context. In fact, managers who fit the highly cosmopolitan profile (for example, those that were multilingual and widely traveled) were rated low by their bosses on how well liked and trusted their peers and other colleagues in their organizations found them to be. This finding revealed a paradoxical dark side for managers whose bosses perceived them as being cosmopolitan: exposure to other cultures through education, expatriate experience, language, and travel are critical to developing the skills needed to be an effective global manager, but these same factors are associated with negative ratings from bosses on at least one facet of effectiveness.

There are several possible explanations for this paradox. Ratiu (1983) has written that international executives are seen as being extremely effective but also as chameleon-like. In other words, the flexibility and innovation global managers bring to bear on their situations may contribute to their being seen as inconstant; therefore, they may be disliked and mistrusted by other people in their organizations. Bennett’s (1993) work on the effects of marginality also provides insight into this paradox. Her work describes how some individuals develop an identity that is independent of culture as a response to spending a considerable amount of time living in different cultures. Their cultural independence enables them to better negotiate between cultures, but at the same time their independence forces a wedge between their relationships and affects perceptions of effectiveness.

In investigating cohort homogeneity as one of the experience variables, we wanted to test the hypothesis that there are situations in which a boss’s ratings of an individual’s effectiveness may be influenced by how similar that individual is to other senior managers (in this case demographics—age, native country, company tenure, education, race, and gender). In three of the four companies, we found modest cohort effects, although not in the direction predicted. These results suggest that being unlike others in terms of education, nationality, gender, and tenure may affect bosses’ perceptions of effectiveness.

How Can Organizations Best Select and Develop Effective Global Managers?

To answer this question it’s necessary to simplify our initial model for understanding and position it as an integrated framework for development. Building upon the significant statistical, albeit modest, relationships that exist between bosses’ effectiveness ratings and four pivotal skills (cultural adaptability, international business knowledge, perspective taking, and skill in the role of innovator), it’s possible to extricate the skills and capabilities unique to the high-global-complexity condition. That is beyond the scope of this report. We have expounded on those ideas to create such a framework in Success for the New Global Manager: How to Work Across Distances, Countries, and Cultures (Dalton, Ernst, Deal, & Leslie, 2002).

Although practical uses of our model find their rightful home in that book, it’s helpful here to discuss some of the relationships that emerged from our study. For example, readers should note the relationship between the five personality variables and the four pivotal skills. Cultural adaptability and international business knowledge are related to neuroticism (negatively) and conscientiousness (positively). This could be interpreted to mean that individuals who are able to tolerate the ambiguity and relativity of what they know (neuroticism) and who possess the determination and persistence to learn new ways of doing things (conscientiousness) may be more likely to acquire the knowledge and skills to do business in appropriate ways in other cultures. Individuals who have some appreciation for their own personality will have a greater appreciation for how hard or easy it might be for them to acquire the skills associated with cultural adaptability and international business knowledge.

Individuals who have high scores on the trait of agreeableness are more likely to be skilled at perspective taking (seeing the world through someone else’s eyes). In other words, these managers have an inclination toward empathy. Although agreeableness is not directly related to effectiveness, it is related to skills associated with taking the perspective of others. One might surmise that managers with low agreeableness scores would have greater difficulty learning the skill of perspective taking.

Individuals who have high scores on the traits of openness and extraversion are also more skilled at playing the role of innovator. These managers are inclined to see novel associations and are able to persuade others to see these new possibilities. Again, knowledge of one’s own personality preferences may help a manager more realistically set his or her development goals.

Looking at the experience variables languages spoken, countries lived in, and past expatriate experience, an individual with some measure of cultural adaptability and international business knowledge is also more likely to speak more languages, have lived in more places, and have been an expatriate. It is possible that these individuals can be encouraged to learn languages, to travel, and to seek out expatriate experience with a focused understanding of what is to be learned from such experiences. Finally, because the number of languages one speaks is statistically related to one’s skill as an innovator, there is the intriguing possibility that managers who speak more than one language might also be those most inclined to see novel associations and make unique connections. This suggests that those managers who aspire to global jobs can gain benefits from trying to learn another language even if they never become proficient enough to conduct business in that language.

Certain skills and capabilities are common to managerial work whether that work is global or domestic. But subsequent examinations of culture tell us that these common characteristics play out differently as the cultural context, country infrastructure, and distance shift and interact. A manager (or anyone, for that matter) able to make that shift will have specialized knowledge and unique personal capabilities.

We propose that individuals wishing to develop such specialized knowledge and capabilities will benefit from understanding themselves and from knowing what experiences facilitate the development of this knowledge and these capabilities (travel, foreign language instruction, and expatriate experience, for example).

Limitations

Although the sample size is international, most cultural regions of the world are severely underrepresented. These data are also influenced by rater bias. Managers rated themselves on all of the personality, role, and capability scales. The shared variance among the independent variables interfered with our ability to use regression methodology.

Finally, the instrumentation was designed by Americans, and the surveys were administered in English. The criterion measures focused primarily on activities that occur inside of the organization, not on activities that occur outside or at the boundaries.

These limitations aside, this research is quantitative in an arena replete with best practices, interview data, and case studies of exceptional individuals. The project has considered and integrated a broad number of variables drawn from a range of theoretical perspectives that offer different kinds of relationships to managerial effectiveness criteria. The subject pool is international and the organizations represent a variety of industry types in diverse locations.

It is our hope that as we have built productively on work done by others, we have also cleared away some of the underbrush for those scholars and practitioners who will follow our investigation with their own.