7. Liberate Your Cost Structures

There are good revenues and bad ones. Good revenues build relationships and repeat business and come with healthy gross margins, often due to the firm's ability to differentiate products and services. This gives it both pricing power, and the ability to continuously cut costs faster than its competition, without hurting relationships and repeat business. Bad revenues are just commodity transactions that push the ecosystem toward even more price-cutting as companies fight for market share. The sell-off of cars in the early 2000s at zero-percent financing arguably falls into the former category, while telemarketing and mass mailings about "You have been pre-approved for a new mortgage" clearly fall in the latter, bad revenue category.

Whichever the case, growth should not come at the expense of profit. As well-known business strategist Peter Drucker puts it, profit is the cost of staying in business.1 In a commoditized world with little pricing power, this means that cost rather than revenue is the real generator of profit. If you cut prices without cutting costs, profits are hurt. If your competitor cuts costs, along with prices, which of you will still be in business tomorrow?

If growth cannot come at the expense of profit, it also will not come from cutting costs. Cost cutting can increase short-term profitability, but it is basically a holding action until revenues can provide the leverage for profits. In the post-NASDAQ, post-9/11 era, with the rapid globalization of the early years of this new century, executives had no choice but to cut costs wherever they could. Cost cutting became the price of staying in business. But it is not a vehicle for growth. Cost cutting can stop the race for growth dead at the starting gate, when managers admit that they think a $10,000 idea could be worth a million in new business, but "budgets are frozen and any travel has to be pre-authorized." The logic of business then shifts from "innovation at a sensible price" to "only costs count." It's the freeze of too much aversion to risk, and without risk there is no growth.

In addition, whether made through mergers and acquisitions, reorganization, or competitive repositioning, aggressive growth initiatives frequently generate massive restructuring costs—as much as 80 percent of profits for many Fortune 500 firms. Companies have to pay severance costs for laying off employees, employees that had been hired for the firm's future expansion. Facilities close, leases are canceled, and long-term assets are "withdrawn," which means that they are no longer assets, they are liabilities.

And yet, the most common executive response is to cut prices, hoping to maintain or increase revenues by taking market share. These dying firms hope they can outlast their competitors, slash costs to increase profits, or buy revenue growth through acquisitions.

The Platform Solution: Changing Cost Structures

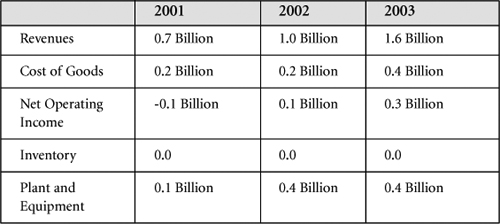

There is an alternative. Table 7.1 presents summary financial data from a Fortune 500 corporation. On the surface, it looks like there is reason for concern.

Table 7.1 Summary Financial Data

Company X sees where high price erosion and high labor-cost growth, coupled with low overall growth, is leading and it doesn't like it. That's why the firm is re-inventing itself: Its new focus on collaborative relationships and selective outsourcing cuts overhead costs by several billion dollars a year, and supply chain management initiatives reduce the incremental cost of supporting transaction volume growth by a few more billions. There is no way that this company's cost cutting will block the inevitable result of price erosion. This is not just cost cutting, however. The company is changing its cost structures. It is building a business platform that enables cost optionality, a balance between fixed and variable costs, coupled with choices about which processes to maintain in-house, which to outsource, and which to co-source.

The platform will likely be expensive to create because there are many up-front costs that include process design and streamlining, facilitating cultural change, skill building, and information technology investments. Even with a platform, competitive intensity and the resulting ecosystem response produces constant price pressure. But the platform is enabling a long-term change in cost structures and revenue growth opportunities. In this example, the company correctly recognizes that its productivity will not come from cost cutting, but from a combination of cost optionality and new collaborations. Cost optionality helps it become more efficient through collaboration and more effective in its value web opportunities.

There are no two ways about it—costs create or limit profits. Cost structures, by contrast, the balance between fixed- and variable-cost options, create or limit growth with profit. They can turn business expansion into immediate and sustainable profits. Platform companies are not locked into the cost profile of the traditional firm, and as component users, they can choose more and more variable-cost processes and services (as does P&G, for instance). As component providers, they can build fixed-cost platforms that exploit scale, specialized add-on skills, and low overhead to service multiple clients (Flextronics). In some instances, component providers can become trusted intermediaries coordinating entire component markets (Li & Fung).

This is the creative economy in action.

The BMW/Magna collaboration illustrates this duality, as do the JC Penney/TAL and P&G/IBM relationships. These transform the client's cost options for capital investment, scaling on demand (pay as you go for what you use, rather than pay up front), and component quality. It also creates an expansion space for the providers, though as they serve many clients, they must themselves take on many of the risks of their clients' now obsolete in-house value chain business model.

When business growth opportunities become cost structure options too, this duality becomes extraordinarily powerful and has already led to a transformation of income statements and balance sheets of growth platform leaders. Compared with their competitors, they use half the working capital per unit of sales, have half the GSA2 overhead, and enjoy at least a similar edge in revenue per employee.

Growth platform companies have four ways to leverage their cost/growth structures and avoid the trap of growth at the expense of cost efficiency, or cost cutting at the expense of growth:

- Directly reduce costs through componentization.

- Shift from fixed-cost operations to variable-cost components.

- Leverage other firms' components.

- Reduce restructuring costs.

Being able to combine all these cost structure options creates a significant competitive edge.

Directly Reduce Costs Through Componentization

Dell's 2003 revenues were a little more than half those of HP. The differences in financial metrics are presented in Table 7.2.3

Table 7.2 Dell Versus HP Financials

Every product that Dell sells is built on standard components, and it has never launched a creative innovation for the industry. Dell's net margin in its core personal computer business is just 3 percent, while its gross margins keep falling. Dell also remains a relatively small firm in its ecosystem, with 15 percent of the personal computer market and just a single digit percentage of servers, storage, and peripherals. It spends just 1.5 percent of revenues on R&D, arguably a core investment for high-tech company innovation. Finally, Dell is also reducing prices by an average of 18 percent annually.

But the financials clearly show that Dell makes a lot of money, even as it drives ecosystem prices lower and lower. While its gross margins drop and remain far below those of HP and other competitors, Dell's net margins maintain it as the industry leader in profitability.

Michael Dell has always stressed that his growth platform was based on componentization, reflecting his assumption of the inevitability of componentization in the high-tech business. Here are some of his most relevant observations, made back in 1998:4

"Companies that were stars ten years ago, the Digital Equipments of this world, had to build massive infrastructures to produce everything a computer needed. They had no choice but to become expert in a wide array of components, many of which had nothing to do with creating value for the customer."

"How can you grow so much faster without all those physical assets? There are fewer things to manage, fewer things to go wrong."

"Outsourcing...is almost always getting rid of a problem a company hasn't been able to solve... That is not what we are doing. We focus on how we can coordinate our activities to create the most value to our customers."

Dell could not have achieved this coordination without the rapidly emerging standardization of industry interfaces. Digital Equipment created the mini-computer and was a growth leader for several decades but it misread trends that Dell spotted and exploited. Digital bet its future on proprietary systems and products, the reverse of componentization, and fell from growth leader to takeover target as a result. By contrast, Dell let go, adopting Microsoft's operating system and the Intel microprocessor as its growth vehicle.

Had UNIX or Apple's Macintosh operating system become the standard, or Motorola's CPU chips led the market, or had Dell tried to simultaneously support DOS, CPM, and UNIX, Dell's strategy would have failed and Michael Dell's earlier statements would amount to an epitaph for a company that bet on the wrong platform.

The point we want to emphasize is the direct linkage between growth and cost structures. By co-sourcing everything that they could, Dell minimized capital investment. There is an immediate saving here because inventory is not an asset but a drain on working capital. Facilities must be able to earn back their investment cost to justify their retention. A microprocessor chip fabrication plant, for example, may cost upwards of a billion dollars to build and is costly to adapt to changing technologies. That's why Dell's philosophy is not to build, but to use.

Dell's real growth began in 1996 when it began to use the Internet as a coordination platform for process components. It provided customized web sites for large customers that incorporated their business rules for procurement along with a wide range of self-management services, including product configuration, software downloading, and troubleshooting. Dell has over 200 business process patents—and no technology patents—and has so fine-tuned its supply chain that its inventory levels are the lowest in the industry, saving capital and enabling Dell to cycle new components into its products in less than two weeks.

By adding storage, servers, printers, and PDAs to its product line, Dell has deliberately targeted the commodity market, and brought companies like EMC and server, printer, and PDA makers onto its customer service and supply chain management platforms, effectively moving them into its commoditization machine. Dell did not have to acquire these companies. If their innovations create successful products, Dell also gains, yet it has very little risk if they fail, since they are only components.

Dell is best known for its inventory management. Inventory, of course, consists of goods that are bought before they are sold, which means that they have a carrying cost. This carrying cost is easily calculated as the weighted average cost of capital for the firm (the opportunity cost for tying up the funds) and the implicit "fee" that investors are charging the company. A firm that does not generate after-tax cash flows that exceed the cost of capital is draining shareholder value. Inventory does this; it is exactly like stashing a few thousand dollars in a mattress. It sits there and cannot be used profitably elsewhere.

The cost of capital for a well-run firm is in the range of 8–16 percent so that $1 million of inventory costs $30,000 for each quarter that it's held. In the meantime, the price the product commands may drop 2 percent—$20,000—or more. Lack of the process base to manage inventory thus provides what we refer to as a business inefficiency penalty on the company of $50,000 per quarter. If the company's net margin is 5 percent, this means that the gross profit on the sale is wiped out by the inventory cost. That is not the way to grow. It was once, but only as long as a company or industry could pass on its cost increases to customers.

Shifting Away from Fixed-Cost Operations

A business component, whether a process, a product, or a commercial service, is a variable-cost opportunity for a buyer and a revenue opportunity for a seller. That has truly profound consequences for business design and is the long-term force behind the growth in global sourcing. For the first time in business history, organizations can integrate components across geography, companies, and organizational functions on any scale.

An extreme example of a completely scale-free business is Yahoo!, which is a value web built on other's components: search engines, stores, financial services, news providers, business auctions, and hundreds of other services, more than would fit on a single page.

These informational components are all variable costs for Yahoo!. It owns none of them. Yahoo! Travel, for example, is a partnership with Travelocity. As with Amazon, it took hundreds of millions of dollars to build the Yahoo! technology and relationship platform, but Yahoo! now has as broad a range of cost options as any firm could enjoy. There is minimal incentive for it to add fixed costs or own and operate any of the services that it offers. Its 2003 financial report shows this cost optionality, outlined in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3 Yahoo!'s Financials5

Yahoo!'s ability to scale via components is shown by comparing its revenue growth to its fixed asset and operating cost growth. This is also the opportunity of the pure online player: a cost structure that is fundamentally variable and that thus leverages flexibility and margins. Yahoo! pays only for what it uses, and component owners typically pay Yahoo! a commission to add their component to its platform.

Such a cost structure may not be well suited to other companies, however. Wal-Mart, for instance, needs stores and facilities, about $52 billion of assets, along with its inventories, which adds on another $25 billion, and the labor costs of over 1 million employees. Its cost of sales is $191 billion on sales of $244 billion. Wal-Mart is moving in the same direction as Yahoo!, though, because it is using its platform to componentize the supply chain and move to a variable-cost structure. Vendor-managed inventory (VMI) is an example of a component that is coordinated through Wal-Mart's platform on a cost basis. Wal-Mart does not "buy" the goods; the supplier stocks the shelf and Wal-Mart pays when the goods are actually sold. Its VMI partnership with P&G transformed their supplier and retailer relationship from control-based to collaboration. P&G stocks the shelves and forecasts future sales trends on the basis of componentized links to Wal-Mart's in-store point of sale data. Wal-Mart carries no costs of inventory for the product.

More and more companies are turning expensive fixed costs into variable costs and improving quality at the same time through what we call an incremental evolution rather than a radical revolution. Many of the examples we have discussed in earlier chapters have moved manufacturing from in-house to component sourcing. Commodity back-office processes that add no value for the company but tie up capital and add to overhead are being outsourced: call centers, document processing, and HR administration are leading examples.

Why Shift the Costs When You Can Avoid Them?

The Internet is a proven vehicle for turning a company's administrative back-office cost into the customer's valued front office. Self-management gives customers convenience, control, and flexibility in handling their relationships with a company, and the company can immediately move overhead into variable costs. Hundreds of instances of just this transformation have made the Web an integral organizational process coordination channel as well as online customer-service channel. Here's just one: 80 percent of the 60 million phone calls Wells Fargo received each year were for account balance information, at a per-call cost of around $10. Self-service via the Web drops this cost to 10 cents or less per call. If Wells Fargo wasn't able to recognize the inherent value of componentizing its customer service, it could well have chosen to outsource its call center overseas, cutting cost by a percentage but never leveraging its architecture to grow.

Much of this customer self-management avoids costs rather than cutting costs. FedEx estimates that it avoided adding more than 600 customer service reps through its web site self-management business componentization.6 Customer, employee, and vendor self-service helped IBM avoid over $5 billion in expenses. IBM simply put customer service, procurement, and e-learning online and reduced the duplicate offline processes. This cost avoidance is a growth enhancer because the increase in revenues does not produce a comparable increase in cost or overhead.

One distinctive feature of companies that componentize their business is that they aggressively push commoditization. They exploit their cost edge not to increase but to cut prices, to reduce margin for component suppliers, not platform players. Amazon cut the price of best-selling books by 50 percent at a time when it was still a long way from making profits;7 this shot across the metaphorical bow of Barnes & Noble was a bet on Amazon's growth platform. Amazon has also absorbed expensive shipping costs as a "free" incentive to customers, but its cost structures mean that it can afford these reductions in margin while its competitors cannot.

In the commodity PC space, Dell has exploited its platform capabilities to drive down prices. On one occasion, when ex-HP Chairman Carly Fiorina announced that earnings would fall below forecast because of industry price-cutting, Dell slashed personal computer prices by 22 percent the very next day.8 It could afford to do so because of its cost structures; it has an overhead of only 9 percent and, because of its direct model and platform capabilities, it only holds four days of inventory. Its low overhead is a direct result of its highly componentized supply chain and innovations in process, rather than product innovation.

Overhead is now the main controllable cost of a business. In the old control economy, raw materials and labor typically amounted to about 85 percent of costs, and overhead was what was left over. In commoditized ecosystems, such as auto parts, consumer electronics, and consumer loans, prices are normalized, and if one player cuts prices, the rest have little choice but to follow. Global sourcing then logically becomes the norm, because componentization and labor costs drop. As this process continues, overhead becomes the main differentiator of financial performance, a frightening situation for any old guard firm.

Overhead is cost that adds nothing to performance. Its only value is negative; when administrative functions fail, they cause disruptions, and when they are handled well, customers get billed, HR flows smoothly, and travel expenses get paid promptly. That's it. The obvious solution is to componentize them and shrink the controllable cost base. GE componentized internal back-office processes. IBM, Sun Microsystems, FedEx, Cisco, Wells Fargo, and Southwest componentize customer ordering and support. Supply chain management and logistics leaders synchronize complex relationships via standard interfaces. Fortune 1000 firms componentize processes via their technology platforms and outsource call centers and HR administration.

Overhead is also the edge for platform-based electronic component suppliers. Their clients operate with 16–20 percent overhead levels, but they can focus their own operations very narrowly and operate with just 3–5 percent overhead. This is achieved through the opposite change: high fixed costs give them economies of scale, but rigidity in the range of services that they provide.

Leveraging Components, Even If They Aren't Your Own

FedEx was "dismissed as an also-ran to UPS" not long ago and to Wall Street, it looked as if FedEx was doomed to years of shrinking revenues and falling margins. Some analysts even went so far as to suggest "FedEx would disappear in a takeover."9 The analysts were wrong, and FedEx has come back by building a bang-up ground network. Its resurgence came from the surprising growth of a ground-delivery service that FedEx "cobbled together" from acquisitions and the use of independent trucking firms.

This shouldn't be surprising to anyone who knows FedEx's history, because FedEx has always been a platform-driven company. It didn't cobble anything together but integrated new business components into its platform.

FedEx's expansion of its ground operations required no restructuring. The only restructuring costs were for early retirement and severance programs in its mature core Express business.

Chairman and founder Fred Smith explains, "there is no other restructuring required, in our opinion, to achieve our margin goals."10 The aggressive expansion that included acquisitions was not a disruption to the organization or a new stress for the culture; it was an enhancement of capabilities.

One analyst highlights the platform payoff for FedEx: "The key decision for FedEx was to resist building a system from scratch."11 Instead, in 1998, it purchased Caliber Systems, owner of Roadway Package System, Roberts Express, Viking Freight, and some regional trucking companies. FedEx also hired independent truckers, operating out of 27 regional hubs, to build FedEx Ground from scratch. FedEx reported that its total investment in freight and ground over the five years (1998–2002) was $3 billion. The truckers immediately benefited from the FedEx technology and process base with scheduling and coordination, and the hubs have long been at the leading edge of automation: Packages that enter are automatically routed through the delivery management system, and FedEx is in the freight and ground delivery package business for what looks like a very reasonable investment.

Technology is a core part of the FedEx platform and has been since 1979, when the COSMOS global tracking system was introduced. In the 1980s, it gave away a 100,000 PCs to large customers, enabling them to self-manage their transactions and accounts. In 1986, it launched SuperTracker, a hand-held barcode scanner, to capture package information, and three years later launched its on-board satellite-based communication system to track vehicles. FedEx was a very early adopter of the Web, providing package tracking for all customers. (UPS was introducing its own innovations, too.) By 1998, FedEx was spending a billion dollars a year on its technology/process infrastructure, on revenues of $10 billion.

FedEx Ground meant a sharp turn away from its Express strategy. A key element had always been its exploitation of airline deregulation of larger freight planes. While its competitors bought space on airline carriers' planes—a variable cost—FedEx built its own airline—a largely fixed cost—of more than 600 planes. FedEx used the very same platform in its Express services to ensure the same level of quality with Ground, and its own cost efficiency but with far more cost optionality; the independent truckers work under incentive-based long-term contracts.

Growth platforms are far more than technology. FedEx's platform, like that of Southwest Airlines, was built on governance rules for mobilizing and rewarding people and for ensuring that they take responsibility and follow the corporate way. One of FedEx's few missteps came in the late 1970s when it acquired a British company during a down period in the UK economy, acquiring a largely unionized labor force strongly opposed to change. FedEx had built a strong set of governance principles and organizational practices that had led to a highly disciplined and motivated culture but this organizational platform did not transfer to the UK firm. After rebuilding, FedEx's UK operation is a leader in Europe, not a laggard, and FedEx's platform reaches out effectively across all of Europe.

In 2003, FedEx extended its platform by purchasing Kinko's for $2.2 billion. A thriving business, Kinko's offers many opportunities for FedEx to grow, including the increased shipping services for the many small businesses that use Kinko's as their office, and the many added extra pickup points. How about storing spare parts for FedEx logistics service customers? The Kinko's locations are in major cities, near business complexes, and are now mini-warehouses that FedEx can use to pick up and deliver parts. Same platform, extended value web.

The competition between FedEx and UPS has been to the benefit of customers and has played a major role in the reshaping of business logistics. Their platform is their strategy. In many instances, they are so integral to customers' operations that they are now part of their customer platform. And that is what collaborative value webs are all about.

The Fixed-Cost Burden

Companies that have a largely variable-cost structure can adjust volumes quickly and easily. They add or reduce costs as they go, and their restructuring charges are low and infrequent. Fixed costs, on the other hand, do not go away so simply. It is sensible for companies to dispose of old facilities when they can replace them with new ones, but is it logical to do the same with people or assets that are not critical to the success of the business and that others can provide on a variable-cost basis?

Shifting to a variable cost, co-sourcing structure helps mitigate these problems. When restructuring charges are a recurring item on the income statement, it is time to rethink cost structures. The platform edge comes from having more options. We do not suggest that companies move to a variable-cost environment as a matter of routine, but we do argue that a fixed-cost structure that results in restructuring charge after restructuring charge is surely not well suited to a changing environment.

Restructuring charges are often huge. One major manufacturer reported operating profit in the third quarter of 2003 of $866 million, but also reported restructuring charges of $501 million: 60 percent of profits. In their annual report, the firm further warns that their inability to implement their planned reorganization may cause them to have insufficient financial resources to carry out research and development. They also cite regional labor regulations and union contracts that may make it impossible to implement such reorganizations. Their industry was busy commoditizing while they are trapped in the death spiral of commodity hell. The result: low utilization ratios at manufacturing facilities, and higher ratios of fixed costs to sales.

Companies can exploit the componentization and platform capabilities to avoid getting stuck with restructuring as a cost of doing business. Another large corporation's Annual Report explains its $700 million, three-year restructuring costs this way: "Reduced full-time equivalent employees... Consolidation of 33 domestic branch offices... The removal of certain hardware, software, and equipment... Withdrawal from certain international operations... Sublease excess facilities... Reduction in administration office space... Write-downs of fixed assets... Initial restructuring charges in a 2001 Workforce reduction of $182 million, Facilities reduction of $139 million, Systems removal costing $61 million." Nowhere do they note that all of these costs might have been avoided through a variable-cost structure.

Finding the Balance Point Between Fixed and Variable Costs

IBM's Global Services organization has developed a useful way of thinking about the optimal cost structure for a firm. The logic is based on the observation that a firm can be fairly sure of some subset of its projected revenues for the coming years.

Here is a hypothetical example for a firm we will call XYZ. Its business plan aims for revenues of $2.3 billion. $1.8 billion of this is fairly certain and XYZ aims to optimize its cost structures to meet this level of sales, focusing on in-house resources. The next $0.3 billion is probable, the remaining $0.2 billion is more uncertain, and there is a possibility that sales could surge if the economy improves and new product introductions are successful. XYZ's planning process relies on handling the risk elements of the plan through variable-cost co-sourcing and value web relationships. The calculations are complex but the logic is clear: Hedge your risks and ensure your efficiency through cost optionality. XYZ develops cost-structure options assuming that the business plan will turn out to be on target. The high fixed-cost plan allows the firm to exploit scale and efficiency, but it loses flexibility and adds substantial risks if the $2.3 billion of revenues do not occur; XYZ then has an exposure of $500 million. That exposure is reduced by increasing the use of variable-cost sourcing.

The two extremes in the model are fixed costs and variable costs. Each has advantages and disadvantages that mostly depend on the predictability of market demand. Together they help define a "balance point" in the optimization of cost structures.

The balance point is essentially risk hedging: distinguishing between stable ongoing business, predictable extension business, and uncertain, at-risk business. The strategic question for any firm is always how to fund the risk growth. For ongoing business, it makes sense to use the firm's platform aggressively to attack overhead and reduce working capital via sourcing of component capabilities. Many fixed costs will remain in place and provide the company with its coordination base and platform foundations, but the result will be a cost-efficient company, bullet-proofed against commoditization.

Growth comes from expanding risk areas, however. This is where a company needs cost flexibility to ensure business flexibility. There are a number of factors to trade-off against each other: investment cost and time, scaling volumes up or down in response to customer demand, and organizational costs of cultural adaptation, new skills, and administrative additions.

No one can provide a reliable and foolproof way of handling growth risk, because if they could it wouldn't be risk, but this key area of business innovation can be handled through platform collaborations and made as much variable cost as is practical.

Each type of growth platform that we discussed in Chapter 6, "Expand Your Growth Space," pushes business more and more toward variable costs rather than fixed costs, but this is not an absolute. There will always be good reason for firms to keep some operations in-house and invest in fixed and intangible assets.

Letting go of fixed assets will help your business grow.

Summary

Growth should never come at the expense of profits, and in a commoditized world, cost, not revenue, is the generator of profit. At the same time, growth never comes from cutting costs alone, at least not in a long-term, sustainable manner. The solution is to change your cost structures, to build a business platform that enables you to find the optimal balance between fixed and variable costs, along with sufficient componentization to allow you to outsource or retain in-house based on the best expected results for your business.