6. Expand Your Growth Space

Li & Fung built a value web with thousands of suppliers, each providing a specific component, such as fabric manufacturing, dyeing, sewing, buttons, yarn making, packing, and shipping. It is able to charge handsomely for its services and has taken over more and more planning and logistics for clients such as the Gap, Calvin Klein, and The Limited. Hong Kong-based TAL Apparel has built an equally effective value web, one that makes 12.5 percent of all dress shirts sold in the United States.1 It, too, is very profitable and has a strong reputation for entrepreneurship. Both companies are expanding across their entire business ecosystem of geography, services, and partners. Neither of them brands the end product but instead strengthens client brands and customer service. And they grow and grow.

Apparel is a horrendously tough business for both manufacturers and retailers. Retail prices affect what manufacturers can charge, and for basic apparel goods, prices have been flat or declining for over a decade. TAL has seen its own prices fall by 20 percent in five years. Levi Strauss, once the producer of premium price jeans, no longer manufactures in the U.S. and now must survive in a competitive environment where the average price of jeans has dropped from $40 in 1998 to $34 in 2003, with large retail chains selling them at $24. In late 2002, the last major U.S. shirt-making facility closed down. Competitive intensity is ever-increasing due to the three interacting forces of globalization, deregulation, and technology.

Technology enables scattered operations to be globally coordinated; both TAL and Li & Fung invest heavily in their technology platforms, which fuel their globalization as country after country moves to expand its activities. In fact, while East Asian growth in apparel making has been fairly flat in recent years, the Caribbean has been increasing capacity at 30 percent per annum.

The World Trade Organization mandated an end to textile quotas, which has led to aggressive expansion in countries like India and Indonesia.

The Internet has also become a contributor to competitive intensity, with Amazon as one of its leaders: In late 2002, Amazon announced that it was teaming up with the Gap, Land's End, Nordstrom, and Target to offer more than 400 popular brands in its Apparel and Accessories Store. This store includes all the features of Amazon's platform, including buyer reviews, catalogs, search, and price comparison services.

The impact of this competitive intensity on the ecosystem is overcapacity everywhere, particularly since, in the apparel industry, componentization is a natural by-product of technology. Instead of manufacturing a shirt, as was the case in the heyday of the textile industry, companies like Li & Fung assemble it, often by coordinating dozens of factories scattered across the globe. TAL goes one step beyond in its relationship with JC Penney because TAL decides what to make and then tells JC Penney what the retailer has bought.

These two Hong Kong-based companies, TAL and Li & Fung, built growth engines in an industry that is truly commodity hell. TAL CEO Dr. Harry Lee transformed the business from a "Take Control" to a "Let Go" strategy, a more nimble and successful response to commoditization for both TAL and its customers. This process was not easy or quick to accomplish. TAL's Take Control strategy had failed; it had relied on a U.S. wholesaler that handled its shirts, so when that company went bankrupt, TAL bought it, but TAL's managers did not understand the wholesaling business—within three years, they'd lost $50 million on the acquisition and shut the company down. Dr. Harry Lee said that the firm lost "their pants and underwear" trying to brand TAL goods in the marketplace.2 TAL's effort to sell branded items in the U.S. through acquiring a Mexican factory met the same fate.

In the 1980s, TAL shifted its business strategy to help other companies work more effectively rather than remain trapped as a low-cost supplier. It built the foundation of its value web through investments in supply chain management and logistics services, enabled by information technology. This made TAL a strong supplier: Clients placed orders and TAL fulfilled them. The company built a strong relationship with retailer JC Penney and, in mid-1995, established a new service where it could replenish Penney's stock in one week, a dramatic improvement over the industry standard of six months. This was a remarkable accomplishment, but other firms were catching up on basic supply chain management.

Spanish clothier Zara had also shortened store replenishment to days and introduced 12,000 different designs a year. The Swedish company Hennes & Mauritz learned to treat fashion goods as if they were "perishable produce: keep it fresh and keep it moving."3 H&M outsourced production to a huge network of 900 factories in 21 countries and focused on speeding up design; it can now move a garment from concept to store floor in as little as three weeks.

Both Zara and H&M have built a successful growth platform to meet their own needs. Zara has close to a thousand stores and makes most of its products in Spain. H&M has grown its number of stores by 75 percent in six years, commands gross margins of over 50 percent, and same store sales are increasing by 4–5 percent a year. Whether or not the two companies can sustain growth is uncertain in the volatile fashion industry. The Gap was once the hottest chain in the United States but struggled abroad, and the Body Shop slipped into a struggle-and-reconstruct situation after years of tremendous growth. These companies built strong value chains and must continue to keep control of them if they are to maintain their edge. As many have found, they can rapidly expand at first, through opportunistic site location and franchising, but then run out of expansion space, sometimes quite literally so, when franchisees find that the franchise has opened another store in their region. The value chain has a relatively fixed length.

TAL uses a different business model, a value web rather than a value chain. TAL CEO Dr. Lee explains that he learned from the firm's failed acquisition of its U.S. wholesaler that inventory management and matching supply to demand were the critical competitive needs, not just product. He saw that JC Penney was warehousing up to nine months of shirt inventory, shirts that were going out of style as they sat. This stock level was twice that of Penney's main competitors. To solve this supply chain failure, he proposed on a visit to Penney's headquarters that TAL supply shirts directly to stores instead of sending bulk orders to JC Penney warehouses.

The idea was quickly rejected and each division of JC Penney had its own objections. Primarily, warehousing said it would be a disaster if TAL did not deliver the right goods to the right store on schedule, while IT worried about incompatibilities between the two computer systems. It was years later that a new commitment to reducing inventories across JC Penney led to the plan being revived and successfully piloted. A few months later, TAL was delivering shirts directly to all of Penney's North American stores and inventories dropped immediately.

The next idea that Lee proposed was the value web leap. Why not have the TAL staff in Hong Kong forecast how many shirts each store would need each week? Penney's existing sales forecasts were often missed, sometimes dramatically overestimating demand and other times resulting in stock-outs of fast-moving items. TAL reasoned that if it could get sales data straight from the stores, it could monitor the customer's pulse and respond instantly to any changes, ordering more fabric and increasing production where needed.

The results have been dramatic: zero inventory for Penney's in-house shirt brands.4 TAL will make and send as little as one custom-made shirt to a store. JC Penney also let go of design and handed it over to TAL. TAL's New York and Dallas teams now come up with a proposed design and within a few months produce and test market 100,000 new shirts. Not all will sell, but the system lets customers, not marketing managers, choose what to buy. A JC Penney executive comments that, "When we can put something on the floor that the customer has already voted on, that's where we make a lot of money."5

TAL is now the world's largest shirt maker. It has extended its value web to add services in the non-physical areas of logistics. Because its technology platform is highly componentized and built on industry interface standards, it has also been able to quickly incorporate new software that enables electronic transactions, replacing the costly trade financing processes that added almost $250 to the cost of each order.

TAL invests in R&D that has led to several industry-leading innovations that it now licenses; a widely praised example is its Pucker-Free seam technology that greatly improves wrinkle-resistant, non-iron shirts. Brooks Brothers was an early adopter of this technology.

TAL is successful because JC Penney let go. The degree of power that JC Penney turned over to TAL is radical. "You are giving away a pretty important function when you outsource your inventory management. That's not something a lot of retailers want to part with."6 In return, TAL also lets go of many common suppliers' rules. For example, TAL will occasionally misestimate a store's requirements. When that happens, TAL picks up the extra cost for shipping by air instead of sea. It synchronizes its main factories in Asia, together with a garment factory in Mexico and a weaving and spinning mill in North Carolina, along with its many suppliers of buttons, zips, thread, fabric, and so on. These components are assembled to provide a commodity good and the result is that JC Penney pays no price premium for its house brands.

Were the shirt retailing business not so constantly pressured by commoditization, there would be little incentive for JC Penney to let go. Were the industry not so componentized, TAL's strategy of fitting the component pieces together would not be practical. Without its growth platform, TAL would have to compete on a control-based strategy in an increasingly difficult business market, but instead, it has growth options everywhere. Ashworth, the leader in "golf-inspired" sportswear, views TAL as key to its being able to keep ahead of commodity competitors. TAL remains a success due to its new capabilities in such areas as trade financing, opportunities to extend its platform into the Asian consumer market and to European customers, and through its distinctive role in helping clients do their own business better.

TAL's value web is a success and a growth engine because of commoditization, not in spite of it.

Where Is Your Firm's Growth Engine?

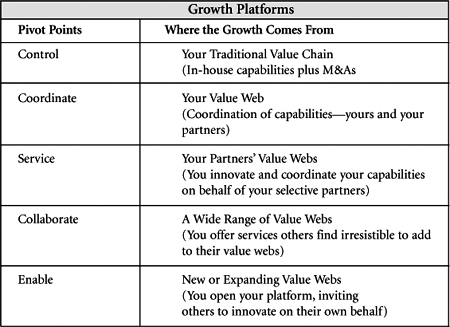

TAL and JC Penney are both letting go, yet they have different growth platforms. How then does a company identify its own platform? By answering one question: Where will our growth come from? We suggest that there are five pivotal choices. We use "pivotal" in the sense that they are the focus—the pivot point—for defining strategic intent and hence the governance, interface standards, and synchronicity of the platform. They are pivotal also in that the choice is crucial and consequential.

Each of the five types of growth platforms can be described by an action: Control, Coordinate, Service, Collaborate, and Enable. Table 6.1 defines these pivot points and the growth associated with each.

Let's explore each in more detail:

- Control—In the power player model, growth comes from perfecting the traditional value chain, growing and managing in-house capabilities, along with mergers and acquisitions. Just about everything is proprietary. There is very little letting go, and little growth too; the control model has a pretty dismal growth record in that regard. A few companies are still able to make it work, though (Southwest Airlines being an excellent example).

- Coordinate—Growth comes from the ability to build a value web and coordinate a wide range of component capabilities, both the firm's own and those provided by expanding its access to outside relationships. The imperative is to build your own value web, making effective use of partners and of creative, rather than reactionary, sourcing models. This is the blueprint for most large companies. P&G is an example of a formerly control-focused company that has made the shift to coordination. Coordinating companies rely on synchronization of relationships but on their own terms. They let go through their strong focus on coordinating value web relationships, especially in supply chain management. This is clearly where JC Penney is heading. The major challenge in making the shift from control to coordination is getting the culture to let go and become truly collaborative. (We explore this key aspect of organizational mobilization in Chapter 8, "From Vision to Results: The Leadership Agenda.")

- Service—Firms grow by innovating and coordinating their own capabilities on behalf of partners. They build tight relationships with selected clients, and grow as their partners move from control to coordination and thus expand their value space. Examples are Magna and Timken in manufacturing, Flextronics and Solectron in electronics, TAL and Li & Fung in retailing, and IBM and Accenture in IT and business processes. Service platform companies grow through their contributions to a componentized ecosystem. It is not coincidental that service platform firms are proliferating in highly commoditized ecosystems, such as car manufacturing and consumer electronics, or that few are household names. They are component "suppliers" that offer more than just supplying things. They even give up their own brand because they are part of a coordinated value web owned by the client. The combination of coordination brand players and service component platform specialists is exemplified in the relationships between JC Penney and TAL, BMW and Magna, and even the HR services that IBM manages for P&G; they generate innovation through components, allowing brand players to get out of the commoditization bind. Their skill is in relationship management, increasingly the differentiator in any commodity business.

- Collaborate—A firm grows through dynamic value web participation by offering a range of services to any client/co-sourcer/partner. FedEx, IBM, and UPS are exemplars in this regard. Collaborative firms offer services such as shipping, payroll processing, call center expertise, and IT operations, providing generic components rather than the industry-specific offerings of service platform companies. They profit and grow by offering the same service to a wide range of customers, their key organizational skill is sales, and their core platform priority is synchronization and reliability of service.

- Enable—A small number of very skilled value web players add to their growth and open their platform capabilities by inviting others to innovate on their behalf. Growth comes as these partners expand and reward the enabler, often in the form of commissions, referrals, and shared business. Amazon and eBay increasingly rely on new uses of their platforms that they do not initiate, but enable. This is an extension of collaboration in that a firm with a distinctive set of platform capabilities offers some of its components to allow other firms to innovate. The enabler gains from fees, through partnerships, and in the creation of new value webs. IBM and P&G have turned their patent portfolios into very profitable licensed components available even to competitors.

These growth pivots are not mutually exclusive. The stronger the platform becomes, the more growth opportunities become available. Here we use stronger in terms of governance rules that expand collaborative roles, the range of standardized technology, process and service interfaces, and synchronicity, scale, reliability, and responsiveness. Remember that a growth platform can expand well beyond its own control spaces into new coordination spaces, service spaces, collaboration spaces, and innovation spaces. The driver of growth is "more" rather than "bigger."

Letting Go: Moving from Control to Coordination

Coordination is the obvious pivot point and blueprint for most large companies. It is the natural evolution from the value chain to a value web because the company stays at the center of its own web. We've seen this move in several of our examples. A.G. Lafley is transforming P&G based on the premise that they will "do what they are best at and nothing more."7 P&G is outsourcing HR administration, IT operations, and the manufacturing of products like Ivory Soap. They are also strengthening their beauty products brands and expanding their value web to include healthcare products like the over-the-counter drug Prilosec.

Wal-Mart's move to coordination actually started with P&G. As Wal-Mart's founder Sam Walton described the story,8 until the mid-1980s Wal-Mart and P&G had a very adversarial relationship. P&G would dictate how much Wal-Mart would sell and at what price. Wal-Mart would, in turn, threaten to drop P&G products or give it bad shelf space. There was no sharing of data, joint planning, or systems coordination. A mutual friend arranged a canoe trip for Sam and Lou Pritchett, P&G's vice president of sales. On the trip, the two men decided to reexamine the adversarial relationship starting with a top executive joint-planning meeting. The result was a plan for Wal-Mart to share its point-of-sales data so that P&G could take responsibility for managing Wal-Mart's inventory. That plan not only changed the relationship between Wal-Mart and P&G, it reduced costs and improved operations for both companies. It also changed forever the way in which Wal-Mart runs its business. That was the starting point for Wal-Mart's componentization and coordination with a wide range of vendors. But first, both Wal-Mart and P&G had to relinquish control and build new coordination capabilities; 18 years later, Wal-Mart is still transforming.

In one of its most recent moves, Wal-Mart is requiring all vendors to put RFID tags on all pallets. At the same time, it is streamlining the distribution centers and working toward item-based RFID tags with shelf readers so that vendors like P&G don't just manage inventory levels, but can deliver directly to stores, refilling depleted shelves and bypassing the distribution centers completely. Wal-Mart should be able to double the volume of goods sold without building another distribution center, according to some industry analysts.

GE is focused on simplification, process entitlement, centralization, and outsourcing to free up resources for innovation. Their role as a coordinator of their own value web is evident in GE Healthcare's centers of excellence. But GE is not just a coordinator, remotely monitoring MR scanners in hospitals, turbines on ships, and railroad services that increase on-time operations. They play a service role in other companyies' value webs in addition to coordinating their own web. Like GE, IBM is known as a coordinator in the hardware and software business, but increasingly plays the service role in other value webs for IT operations and HR administration.

Dell may be the best known of the value web coordinators, synchronizing a complex value web that includes many players. Yet Dell owns and operates very little of its "core" business and does almost no research. Like P&G and Wal-Mart, it has a much narrower focus than a traditional control player, but Dell also provides a glimpse of the future where competitors start new businesses in ecosystems that have componentized or are in the process of componentizing. In an industry bifurcating between the high-value solutions providers and the lower-end component space, Dell has chosen to build its business upon industry-standard parts and components. Microsoft does the software R&D and recruits and coordinates thousands of application partners, Intel makes the microprocessors, and component manufacturers design and make printers, displays, memory chips, and motherboards. Dell couldn't afford to create every piece of the value chain, so Dell built a platform that synchronizes all activities based on its direct-sell model.

The move to coordination is a natural one for control players, but it's not easy; it takes focus and discipline. As the world componentizes, more companies will enter an ecosystem that is already componentized and they won't go through the decomposition process.

More Than Service with a Smile

Service platform companies are built on commodity components that they augment in some way—generally through specialized, highly focused service and a commitment to quality. An exemplar in this regard is American Axle and Manufacturing. Its founder, Richard Dauch, played a major role as a top executive in Chrysler's rejuvenation in the 1980s. After he left Chrysler, Dauch scouted for new opportunities in manufacturing. One came from another of his previous employers, GM, which was busy restructuring and had put up for sale five old Detroit axle and drive train plants. Some of the machinery was 40 years old and the plants were in total disrepair.

And yet their components were critical for GM. Indeed, as part of the purchase agreement, GM agreed to keep buying most of the plants' output if quality was improved. In response, Dauch built a new service platform, with GM as its main client. Today, about 80 percent of AAM's total output is still purchased by GM, though AAM is rapidly adding new clients, including domestic and foreign truck makers. In addition to rebuilding and modernizing the plants, Dauch upgraded his employee base; a ninth-grade education had been the norm, and now the average employee has two years of college. The average age dropped from 50 to 39 and the workforce became more diversified, though still predominantly male. AAM has doubled productivity and has been profitable in every year of its decade-old existence, with sales of over $4 billion. AT Kearney ranked it as the best financial performer among automotive parts "Tier I" suppliers.

People are one key element of AAM's platform governance. Another is its Factory Information System that monitors every aspect of operations. Dauch is a stickler for measuring everything the company does, down to the micrometer scale for components, a level at which differences are invisible to the human eye. AAM largely grew with the surge in GM's light truck business, an example of how clients' value web growth is the driver for service platform growth. AAM has been able to bring jobs back from Mexico and win contracts for work previously done in China, both bucking the predominant trend in the automotive industry. Dauch says that he is building a low-cost country in Detroit.

Magna and Flextronics, described earlier, are paralleling AAM's path. They focus on services to a well-defined range of clients, compete on price—as they must in a commodity environment—but differentiate through added services. In AAM's case, the differentiator is quality management, for Magna it is engineering and production expertise, and for Flextronics, scale, reliability, and low overhead. In each case, large manufacturers come to rely on them for commodity components that many other players can offer, but they add a platform capability that few can equal. They live with commoditization, focusing their innovation and capital investment on quality and process improvements.

By changing from suppliers to service linkers, Magna, Flextronics, TAL, Li & Fung, AAM, and IBM Global Services complement the moves of firms like BMW, P&G, and JC Penney from control to coordination. Together, the companies create a symmetry of capabilities: GM gets quality at the best price and AAM gets volume. JC Penney gets greatly improved inventory management and capital efficiency and TAL gains growth. The result is the synchronization of a value web that in the old days could not exist. In the old days, don't forget, GM made almost all its own parts, JC Penney managed its own inventory, and BMW made its own cars. There is a growth engine that is allowing large companies to let go of their in-house operations model, as service platform firms pick up more and more business on their behalf.

Most service firms also have to be coordinators of their own value web. They build and enhance components that differentiate them and let go of those that don't: If they retain ownership of components that don't differentiate them and are available on the open market, they waste capital and scarce management resources, reducing growth opportunities.

Creating Markets Through Collaboration

The notion of "complementarity" is extended from specialist component services to general purpose ones that companies such as UPS, FedEx, First Data, and eBay have as their growth platform strategy. These firms all fuel their growth through customer growth and play an active role in supporting that growth. If they were just suppliers, they would grow or shrink with the overall economy, as most companies do. Instead, they exploit their platform to offer partners and customers components that are flexible and enable innovation.

FedEx and UPS

Here are a few examples that have worked for FedEx and UPS, many of which we have discussed earlier:

- Deploy components on demand, as needed—Using FedEx or UPS requires no long-term planning or new facilities.

- Contribute to coordination across the client value space—Amazon is as much a shipping company as an order fulfillment retailer, and their order-to-delivery processes are fully synchronized with FedEx and UPS.

- Transform cost structures—FedEx and UPS are variable cost to their customers.

- Open up collaborative and service opportunities to create new capabilities—Fender's new synchronization of its delivery and service for top-end guitars exemplifies this type of collaboration.

- Add to customer flexibility and adaptiveness as it creates specialized services for select customers—HP offers printer repairs without ever being involved in the process. UPS does this by exploiting its core pick-up and delivery services, augmented by warehousing, parts inventory management, and repair technicians.

First Data

From the time that the first bank credit card was issued in 1951, Visa International, Inc. and MasterCard International, Inc. have dominated the credit card business. These two associations were formed by the member banks to provide card services, including brand marketing and back-office switching networks. They started out as a service for the banks but in an effort to strengthen the brand, they exerted more control, limiting the cards that member banks could issue and mandating which cards retailers could handle. Times have changed, and with the bank consolidation of recent years, over 50 percent of cards are issued by less than a dozen banks. The Internet has made it far simpler to build networks, and card transaction volumes are also increasing rapidly with debit card transactions, the most rapidly growing segment of the market. Squeezed by lower profit margins and the transaction costs associated with paper-based debit card processing, retailers are actively looking for ways to reduce their transaction costs.

First Data offers these retailers a viable alternative. First Data was founded in 1992 when American Express decided to spin off its credit card processing operations as an independent company. Between 1992 and 2002, revenue increased by 500 percent and profits by 700 percent. Today, First Data provides card-processing services for over 1,400 card issuers with 398 million accounts on file, processing 37 percent of all credit card transactions.9 In early 2004, they completed the purchase of Concord EFS, giving First Data merchant services that enables millions of merchants worldwide to accept any type of electronic payment easily and securely. Today, First Data handles more than half of the PIN-debit transaction market through its Star network.

First Data offers banks card-processing services, and while they continue to expand those services, they also leverage their collaborative platform to offer banks additional services like co-branded cards, in competition with Visa and MasterCard. They can offer the banks a larger share of each transaction because of their efficient operations and expanding transaction volume. For the merchants, they offer a lower cost, more secure debit card service, and with the explosive growth in debit cards, First Data is leveraging that growth because of their platform and win-win-win approach to the game.

eBay

eBay illustrates the same principles of growth through collaboration. It provides a service that millions of customers use every day, and leverages the collaborative pivot point to enable customer innovations through the use of its platform. For example, government agencies discovered that they could see as much as three times the price through eBay as they do with regular public auctions. Retailers use eBay to sell returned goods or to dispose of excess inventory. Many small businesses have transformed their own operations through access to the eBay technology and process platform (including payments, support, and training). eBay's chairman estimates that there are now well over 100,000 such small-scale entrepreneurs who use eBay as their business infrastructure. It is the infrastructure that differentiates eBay as collaborator and makes the firm much more than an auction transaction site.

BIG Ideas

Once large companies started to shift from control to coordination, many new value spaces opened up. Consider pharmaceutical research and development, where hospitals, companies, and individuals have become part of the value webs and large firms co-source the innovation. Product development may not even be crucial to certain firms. Analysts Scott Anthony and Clayton Christensen10 point to a small company, BIG (Big Idea Group), which acts as a link between "idea generators" and large companies looking for new product opportunities in such industries as toy making, housewares, and do-it-yourself home improvements. BIG rents a conference room and invites in literally anyone interested in pitching their ideas to a panel of experts. It winnows the ideas and takes the best to potentially interested clients, and then works with them to turn concept into product. BIG thus becomes a component in their larger enterprise capabilities and helps them think about innovation as a collaboration opportunity rather than an in-house monopoly.

Enabling Customer and Partner Innovation

eBay enables customer innovation through the use of its platform. As its customers grow, eBay grows. The next extension of such collaboration is to explicitly make your own platform the enabler of customer innovation. Platforms have become an invitation to coordinate component capabilities, to offer services, to mutually benefit from collaborative linkages, and to invent.

The most intriguing innovator in this regard is Amazon. In a book that is focused on generating profitable growth, it may seem somewhat odd for us to pick Amazon as an exemplar. After all, it took a lot of investor capital to build the Amazon platform, and it took years for the company to be profitable. But Amazon is a platform company, and it has grown and grown. This is a $5 billion business built from scratch, in less than 10 years. Had it been just a dot-com and transaction machine, it probably would have failed. The company did made mistakes and it has had to readjust its strategy more than once, but underlying Jeff Bezos's strategy has always been platform.

The core of the Amazon platform was their principle of becoming "the best place to find, discover, and buy any product or service available online."11 This was the brand-building control stage of Amazon's business evolution. "We intend to leverage our Internet platform to expand the range of products and services offered to our customers"12 became the story during the coordination stage. Our "third-party channel allows us to provide other companies with a set of e-commerce services and tools for the sale of their goods and services. We have third-party seller relationships with ToysRus.com, Inc.; Target Corporation; Circuit City Stores, Inc.; the Borders Group; Waterstones; Expedia, Inc...."13

Early in its development, Amazon tried to own relationships via equity positions in dot coms, including drugstore.com, pets.com, and living.com. Most of those were unsuccessful but Amazon remains very much in business. Having evolved its strategy, it now offers a "home" to retailers, its thousands of associates, and technology innovators. Bezos never thought of Amazon as a bookseller or even a retailer, but an infrastructure. That infrastructure helped rescue Toys "R" Us, and provided a viable way for Borders to "create" an Internet ordering channel without Borders operating its own ecommerce site. Amazon now gets over 20 percent of its unit sales, at a 15 percent commission, via other merchants. Amazon had already built the platform. These vendors help Amazon realize a bigger return.

Its most striking innovation was opening up its technology platform to outsiders. "Bit by bit, just like its Washington neighbor [Microsoft] did two decades ago, Amazon is building a platform: a stack of software on which thousands or millions of others can build businesses that in turn will bolster the platform in a self-reinforcing cycle."14 Merchants are incorporating Amazon web services software into their own systems; over 35,000 programmers have downloaded the free development kit. An example of business innovation via the Amazon platform is an individual who started selling books through Amazon in 2002. He then learned about an Amazon program that lets users scan a book's ISBN number and retrieve new and used sales information. He can now instantly see the going price for any used book on Amazon and can use this information when he visits thrift stores or yard sales to pick out maximally profitable books. Using this information, he has more than doubled his revenues from $100,000 to $250,000. That's what happens when you open your platform and invite your customers to innovate.

Amazon's growth comes from others' growth as well as its own.

Where does your company's growth come from?

Growth Options and Opportunities

A business growth platform is an enabler, a springboard, a foundation, and a coordination mechanism. In and of itself, it does not generate growth, but it creates options that are not available to firms trapped in commodity hell. But you can't see these options until you truly let go to grow because many are opportunistic and unpredictable, coming from shifts in the environment, new potential partnerships, and innovations in how business components are combined and deployed.

Here are just a few of the platform owner's growth advantages:

- Once a platform is in place, adding new capabilities is an incremental move instead of a strategic investment. That favorably transforms both risk and investment cost. It may take many years and hundreds of million of dollars to build a platform with the scale and capabilities of an Amazon, and it unquestionably demands sustained executive leadership to establish the governance rules and roles of a GE. Once in place and reliable, however, the platform will enable you and your partners the flexibility needed to adjust to new demands in the ecosystem.

- Partnerships are then only limited by the standardized interfaces that the platform can support: technology interfaces, process interfaces, and customer interfaces.

- Growth is not limited to internal development. The most powerful way to create growth is through other companies' growth, via collaborations that provide mutual benefits. The platform also binds the partners so that there is less likelihood of a component-only player disrupting the relationship on the basis of price.

- The nature of innovation changes from something special and unique to a process of everyday opportunistic experimentation and advances along many process, service, relationship, and product fronts.

- Platform players have expanding and collaborative co-sourcing options, to a degree that the term "outsourcing" becomes a misnomer. Co-sourcing, the collaborative creation of value web-based process capabilities, where each player brings distinctive strengths, adds value; it doesn't reduce costs.

- New organizational structures and coordination processes can be quickly created to reflect the ever-evolving business ecosystem.

Lest we seem to be promising the moon, options are only options; they are not sure things. Our position is obviously one of advocacy, and we aim to convince you, our reader, that a platform-centered view of the growth opportunity is a necessity. There is danger, and at times we may underplay the complexities, uncertainties, and risks. Moreover, there are no guarantees in business and, while platform-based leaders have a decided edge in growth and innovation, other factors can erode or even cancel out that edge.

American Airlines dominated every area of innovation and performance in the 1970s through the early 1990s, with Southwest moving along a very different business growth path. American's platform gave it an edge in launching the first frequent flyer program, and it was only American that for many years linked information across passenger, marketing, reservations, and planning. It was able to use this synchronized information as the base for its hubbing strategy. At the time, Chairman Robert Crandall stated that given the choice of selling off Saber, its reservation system, or the airline, he would sell the airline.

Meanwhile, Southwest Airlines avoided hubbing in favor of point-to-point service along selected routes, and standardized on a single plane, the Boeing 737, which reduced maintenance costs, simplified processes, and reduced inventory needs. It componentized its route structures, and its governance policies placed a huge emphasis on employee relationships because employees were the core of its platform. Southwest treated reservations as an operational commodity, whereas for American, it was a major element in its strategic innovation.15

In the early 1990s, American's operations platform was the base for its success, but in an era of change, flexibility is a key to success. In the airline business, change comes quickly and successful platforms can be replaced by innovative new platforms overnight. Platforms wear out and an operations platform does not generate growth, though it provides the functions and capabilities to move with growth. Operations platforms provide tremendous efficiencies and frequently grow over time. They often lack the flexibility required when major discontinuities occur, however.

Sabre Holdings Corp., spun off from American in 2000, has invested more than $100 million to transform its operational platform into a growth platform. They are creating a new way of doing business, a component-based platform that will enable Sabre to transition from a transaction service to a service value web, providing components that will enable travel agents to redesign their own businesses.

Southwest recognized early on the commoditized future and built a component platform that it leverages every day to grow.

Summary

Once you've created a flexible, integrated platform, profitable growth comes just as much from expanding into new market segments as being more efficient within your own segment. With the three interacting forces of deregulation, globalization, and technology comes greater competitive intensity too, so growth must come from new market segments to be sustainable. The key question remains: Where is your firm's growth engine?