CHAPTER 18 Revenue Recognition

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe and apply the revenue recognition principle.

- Describe accounting issues for revenue recognition at point of sale.

- Apply the percentage-of-completion method for long-term contracts.

- Apply the completed-contract method for long-term contracts.

- Identify the proper accounting for losses on long-term contracts.

- Describe the installment-sales method of accounting.

- Explain the cost-recovery method of accounting.

It's Back

Several years after passage, the accounting world continues to be preoccupied with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Unfortunately, SOX did not solve one of the classic accounting issues—how to properly account for revenue. In fact, revenue recognition practices are the most prevalent reasons for accounting restatements. A number of the revenue recognition issues relate to possible fraudulent behavior by company executives and employees.

As a result of such revenue recognition problems, the SEC has increased its enforcement actions in this area. In some of these cases, companies made significant adjustments to previously issued financial statements. As Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant of the SEC, indicated, “When people cross over the boundaries of legitimate reporting, the Commission will take appropriate action to ensure the fairness and integrity that investors need and depend on every day.”

Consider some SEC actions:

- The SEC charged the former co-chairman and CEO of Qwest Communications International Inc. and eight other former Qwest officers and employees with fraud and other violations of the federal securities laws. Three of these people fraudulently characterized nonrecurring revenue from one-time sales as revenue from recurring data and Internet services. The SEC release notes that internal correspondence likened Qwest's dependence on these transactions to fill the gap between actual and projected revenue to an addiction.

- The SEC filed a complaint against three former senior officers of iGo Corp., alleging that the defendants collectively caused iGo to improperly recognize revenue on consignment sales and products that were not shipped or that were shipped after the end of a fiscal quarter.

- The SEC filed a complaint against the former CEO and chairman of Homestore Inc. and its former executive vice president of business development, alleging that they engaged in a fraudulent scheme to overstate advertising and subscription revenues. The scheme involved a complex structure of “round-trip” transactions using various third-party companies that, in essence, allowed Homestore to recognize its own cash as revenue.

- The SEC claims that Lantronix deliberately sent excessive product to distributors and granted them generous return rights and extended payment terms. In addition, as part of its alleged channel stuffing and to prevent product returns, Lantronix loaned funds to a third party to purchase Lantronix products from one of its distributors. The third party later returned the product. The SEC also asserted that Lantronix engaged in other improper revenue recognition practices, including shipping without a purchase order and recognizing revenue on a contingent sale.

![]() CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

CONCEPTUAL FOCUS

- See the Underlying Concepts on pages 1043, 1057, 1068, and 1069.

- Read the Evolving Issue on this page.

![]() INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

INTERNATIONAL FOCUS

- See the International Perspectives on pages 1042, 1063, and 1079.

- Read the IFRS Insights on pages 1109–1115 for a discussion of:

- Long-term contracts

- Cost-recovery method

Though the cases cited involved fraud and irregularity, not all revenue recognition errors are intentional. For example, in April 2005 American Home Mortgage Investment Corp. announced that it would reverse revenue recognized from its fourth-quarter 2004 loan securitization and would recognize it in the first quarter of 2005 instead. As a result, American Home restated its financial results for 2004.

So, how does a company ensure that revenue transactions are recorded properly? Some answers will become apparent after you study this chapter.

Sources: Cheryl de Mesa Graziano, “Revenue Recognition: A Perennial Problem,” Financial Executive (July 14, 2005), www.fei.org/mag/articles/7-2005_revenue.cfm; and S. Taub, “SEC Accuses Ex-CFO of Channel Stuffing,” CFO.com (September 30, 2006).

Evolving Issue REVENUE RECOGNITION

Evolving Issue REVENUE RECOGNITION

This chapter provides the present GAAP related to revenue recognition as of February 28, 2013. It is highly likely that later in 2013, the FASB and IASB will issue a new converged pronouncement on revenue recognition. For the most recent information concerning how the new guidelines will impact revenue recognition, go to the book's companion website, www.wiley.com/college/kieso.

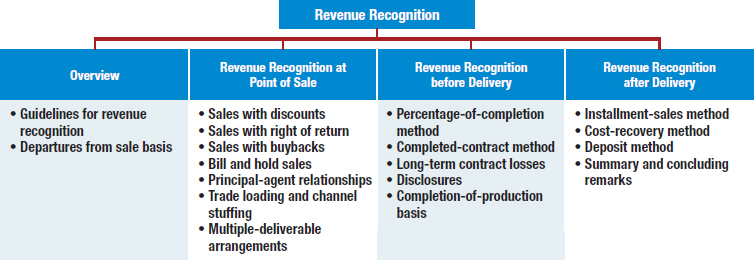

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 18

As indicated in the opening story, the issue of when revenue should be recognized is complex. The many methods of marketing products and services make it difficult to develop guidelines that will apply to all situations. This chapter provides you with general guidelines used in most business transactions. The content and organization of the chapter are as follows.

OVERVIEW OF REVENUE RECOGNITION

Most revenue transactions pose few problems for revenue recognition. This is because, in many cases, the transaction is initiated and completed at the same time. However, not all transactions are that simple. For example, consider a customer who enters into a mobile phone contract with a company such as Verizon. The customer is often provided with a package that may include a handset, free minutes of talk time, data downloads, and text messaging service. In addition, some providers will bundle that with a fixed-line broadband service. At the same time, customers may pay for these services in a variety of ways, possibly receiving a discount on the handset, then paying higher prices for connection fees, and so forth. In some cases, depending on the package purchased, the company may provide free applications in subsequent periods. How then should the various pieces of this sale be reported by Verizon? The answer is not obvious.

It is therefore not surprising that a recent survey of financial executives noted that the revenue recognition process is increasingly more complex to manage, prone to error, and material to financial statements compared to any other area in financial reporting. The report went on to note that revenue recognition is a top fraud risk and that regardless of the accounting rules followed (GAAP or IFRS), the risk or errors and inaccuracies in revenue reporting is significant.1

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

The FASB and IASB have a joint project to improve the accounting for revenue.

Indeed, both the FASB and the IASB indicate that the present state of reporting for revenue is unsatisfactory. IFRS is criticized because it lacks guidance in a number of areas. For example, IFRS has one basic standard on revenue recognition—IAS 18—plus some limited guidance related to certain minor topics. In contrast, GAAP has numerous standards related to revenue recognition (by some counts over 100), but many believe the standards are often inconsistent with one another. Thus, the accounting for revenues provides a most fitting contrast of the principles-based (IFRS) and rules-based (GAAP) approaches. While both sides have their advocates, the FASB and IASB recognize a number of deficiencies in this area.2

Unfortunately, inappropriate recognition of revenue can occur in any industry. Products that are sold to distributors for resale pose different risks than products or services that are sold directly to customers. Sales in high-technology industries, where rapid product obsolescence is a significant issue, pose different risks than sales of inventory with a longer life, such as farm or construction equipment, automobiles, trucks, and appliances.3 As a consequence, as discussed in the opening story, restatements for improper revenue recognition are relatively common and can lead to significant share price adjustments.

Guidelines for Revenue Recognition

Revenue arises from ordinary operations and is referred to by various names such as sales, fees, rent, interest, royalties, and service revenue. Gains, on the other hand, may or may not arise in the normal course of operations. Typical gains are gains on sale of noncurrent assets or unrealized gains related to investments or noncurrent assets. The primary issue related to revenue recognition is when to recognize the revenue.

As indicated in Chapter 2, the revenue recognition principle developed by the FASB and IASB in a recent exposure draft indicates that companies recognize revenue in the accounting period when a performance obligation is satisfied. Until new revenue recognition rules are adopted, existing GAAP guidelines for revenue recognition are quite broad. On top of the broad guidelines, certain industries have specific additional guidelines that provide further insight into when revenue should be recognized. The revenue recognition principle under current GAAP provides that companies should recognize revenue4 (1) when it is realized or realizable, and (2) when it is earned.5 Therefore, proper revenue recognition revolves around three terms:

- Revenues are realized when a company exchanges goods and services for cash or claims to cash (receivables).

- Revenues are realizable when assets a company receives in exchange are readily convertible to known amounts of cash or claims to cash.

- Revenues are earned when a company has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues—that is, when the earnings process is complete or virtually complete.6

Four revenue transactions are recognized in accordance with this principle:

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

Revenues are inflows of assets and/or settlements of liabilities from delivering or producing goods, providing services, or other earning activities that constitute a company's ongoing major or central operations during a period.

- Companies recognize revenue from selling products at the date of sale. This date is usually interpreted to mean the date of delivery to customers.

- Companies recognize revenue from services provided, when services have been performed and are billable.

- Companies recognize revenue from permitting others to use enterprise assets, such as interest, rent, and royalties, as time passes or as the assets are used.

- Companies recognize revenue from disposing of assets other than products at the date of sale.

These revenue transactions are diagrammed in Illustration 18-1.

The preceding statements are the basis of accounting for revenue transactions. Yet, in practice there are departures from the revenue recognition principle. Companies sometimes recognize revenue at other points in the earning process, owing in great measure to the considerable variety of revenue transactions.7

Departures from the Sale Basis

An FASB study found some common reasons for departures from the sale basis.8 One reason is a desire to recognize earlier than the time of sale the effect of earning activities. Earlier recognition is appropriate if there is a high degree of certainty about the amount of revenue earned. A second reason is a desire to delay recognition of revenue beyond the time of sale. Delayed recognition is appropriate if the degree of uncertainty concerning the amount of either revenue or costs is sufficiently high or if the sale does not represent substantial completion of the earnings process.

This chapter focuses on two of the four general types of revenue transactions described earlier: (1) selling products and (2) providing services. Both of these are sales transactions. (In several other sections of the textbook, we discuss the other two types of revenue transactions—revenue from permitting others to use enterprise assets, and revenue from disposing of assets other than products.) Our discussion of product sales transactions in this chapter is organized around the following topics:

- Revenue recognition at point of sale (delivery).

- Revenue recognition before delivery.

- Revenue recognition after delivery.

Illustration 18-2 depicts this organization of revenue recognition topics.

What do the numbers mean? LIABILITY OR REVENUE?

Suppose you purchased a gift card for spa services at Sundara Spa for $300. The gift card expires at the end of six months. When should Sundara record the revenue? Here are two choices:

- At the time Sundara receives the cash for the gift card.

- At the time Sundara provides the service to the gift-card holder.

If you answered number 2, you would be right. Companies should recognize revenue when the obligation is satisfied—which is when Sundara performs the service.

Now let's add a few more facts. Suppose that the gift-card holder fails to use the card in the six-month period. Statistics show that between 2 and 15 percent of gift-card holders never redeem their cards. So, do you still believe that Sundara should record the revenue at the expiration date?

If you say you are not sure, you are probably right. Here is why: Certain states do not recognize expiration dates, and therefore the customer has the right to redeem an otherwise expired gift card at any time. Let's say for the moment we are in one of these states. Because the card holder may never redeem, when can Sundara recognize the revenue? In that case, Sundara would have to show statistically that after a certain period of time, the likelihood of redemption is remote. If it can make that case, it can recognize the revenue. Otherwise, it may have to wait a long time.

Unfortunately, Sundara may still have a problem. It may be required to turn over the value of the spa services to the state. The treatment for unclaimed gift cards may fall under the abandoned-and-unclaimed-property laws. Most common unclaimed items are required to be remitted to the states after a five-year period. Failure to report and remit the property can result in additional fines and penalties. So if Sundara is in a state where unclaimed property must be sent to the state, Sundara should report a liability on its balance sheet.

New federal laws enacted in 2010 added additional complexity for gift-card issuers. The Federal Reserve rules expand disclosure requirements to consumers and put restrictions on dormancy, inactivity, and service fees, which can kick in only after a consumer has not used a gift card for at least a year. It also generally prohibits the sale or issuance of gift cards if they have an expiration date of less than five years. While the legislation aims to improve consumer protections, it may compete with a morass of conflicting state laws. The biggest challenge for gift-card programs is to determine on a state-by-state basis whether or not their gift-card programs are compliant. As one analyst noted, “you need three sets of books—GAAP books, tax books, and what I'll call legal books.” So while customers and marketing departments love gift cards, they can create headaches for the finance department.

Sources: PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Issues Surrounding the Recognition of Gift Card Sales and Escheat Liabilities,” Quick Brief (December 2004); and R. Banham, “Looking in the Mouth of the Gift Card,” CFO.com (September 1, 2011).

REVENUE RECOGNITION AT POINT OF SALE (DELIVERY)

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe accounting issues for revenue recognition at point of sale.

According to the FASB's Concepts Statement No. 5, companies usually meet the two conditions for recognizing revenue (being realized or realizable and being earned) by the time they deliver products or render services to customers.9 Therefore, companies commonly recognize revenues from manufacturing and selling activities at point of sale (usually meaning delivery).10 Implementation problems, however, can arise. We discuss some of these problematic situations on the following pages.

![]() See the FASB Codification section (page 1086).

See the FASB Codification section (page 1086).

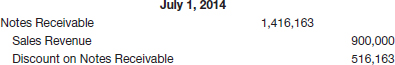

Sales with Discounts

Any trade discounts or volume rebates should reduce consideration received and reduce revenue earned. In addition, if the payment is delayed, the seller should impute an interest rate for the difference between the cash or cash equivalent price and the deferred amount. In essence, the seller is financing the sale and should record interest revenue over the payment term. Illustrations 18-3 and 18-4 provide examples of transactions that illustrate these points.

In this case, Sansung makes the following entry on March 31, 2014.

![]()

Assuming that Sansung's customers meet the discount threshold, Sansung makes the following entry.

![]()

If Sansung's customers fail to meet the discount threshold, Sansung makes the following entry upon payment.

![]()

As indicated in Chapter 7 (page 352), Sales Discounts Forfeited is reported in the “Other revenue” section of the income statement.

In some cases, companies provide cash discounts to customers for a short period of time (often referred to as prompt settlement discounts). For example, assume that terms are payment due in 60 days, but if payment is made within 5 days, a 2 percent discount is given. These prompt settlement discounts should reduce revenues, if material. In most cases, companies record the revenue at full price (gross) and record a sales discount if payment is made within the discount period.

When a sales transaction involves a financing arrangement, the fair value is determined either by measuring the consideration received or by discounting the payment using an imputed interest rate. The imputed interest rate is the more clearly determinable of either (1) the prevailing rate for a similar instrument of an issuer with a similar credit rating, or (2) a rate of interest that discounts the nominal amount of the instrument to the current sales price of the goods or services. [2] This issue is addressed in Illustration 18-4.

The journal entry to record SEK's sale to Grant Company is as follows (ignoring the cost of goods sold entry).

SEK makes the following entry to record interest revenue.

![]()

Sales with Right of Return

Whether cash or credit sales are involved, a special problem arises with claims for returns and allowances. In Chapter 7, we presented the accounting treatment for normal returns and allowances. However, certain companies experience such a high rate of returns—a high ratio of returned merchandise to sales—that they find it necessary to postpone reporting sales until the return privilege has substantially expired.

For example, in the publishing industry, the rate of return approaches 25 percent for hardcover books and 65 percent for some magazines. Other types of companies that experience high return rates are perishable food dealers, distributors who sell to retail outlets, recording-industry companies, and some toy and sporting goods manufacturers. Returns in these industries are frequently made either through a right of contract or as a matter of practice involving “guaranteed sales” agreements or consignments.

Three alternative revenue recognition methods are available when the right of return exposes the seller to continued risks of ownership. These are (1) not recording a sale until all return privileges have expired; (2) recording the sale, but reducing sales by an estimate of future returns; and (3) recording the sale and accounting for the returns as they occur. The FASB concluded that if a company sells its product but gives the buyer the right to return it, the company should recognize revenue from the sales transactions at the time of sale only if all of the following six conditions have been met. [3]

- The seller's price to the buyer is substantially fixed or determinable at the date of sale.

- The buyer has paid the seller, or the buyer is obligated to pay the seller, and the obligation is not contingent on resale of the product.

- The buyer's obligation to the seller would not be changed in the event of theft or physical destruction or damage of the product.

- The buyer acquiring the product for resale has economic substance apart from that provided by the seller.

- The seller does not have significant obligations for future performance to directly bring about resale of the product by the buyer.

- The seller can reasonably estimate the amount of future returns.

What if the six conditions are not met? In that case, the company must recognize sales revenue and cost of sales either when the return privilege has substantially expired or when those six conditions subsequently are met, whichever occurs first. In the income statement, the company must reduce sales revenue and cost of sales by the amount of the estimated returns.11

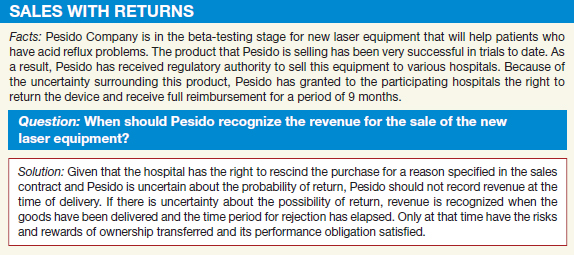

An example of a return situation is presented in Illustration 18-5.

Companies may retain only an insignificant risk of ownership when a refund or right of return is provided. For example, revenue is recognized at the time of sale (even though a right of return exists or refund is permitted), provided the seller can reliably estimate future returns. In this case, the seller recognizes an allowance for returns based on previous experience and other relevant factors.

Returning to the Pesido example, assume that Pesido sold $300,000 of laser equipment on August 1, 2014, and retains only an insignificant risk of ownership. On October 15, 2014, $10,000 in equipment was returned. In this case, Pesido makes the following entries.

At December 31, 2014, based on prior experience, Pesido estimates that returns on the remaining balance will be 4 percent. Pesido makes the following entry to record the expected returns.

The Sales Returns and Allowances account is reported as contra revenue in the income statement, and Allowance for Sales Returns and Allowances is reported as a contra account to Accounts Receivable in the balance sheet. As a result, the net revenue and net accounts receivable recognized are adjusted for the amount of the expected returns.

Sales with Buybacks

If a company sells a product in one period and agrees to buy it back in the next period, has the company sold the product? As indicated in Chapter 8, legal title has transferred in this situation. However, the economic substance of this transaction is that the seller retains the risks of ownership. Illustration 18-6 provides an example of a sale with a buyback provision.

Morgan records the sale and related cost of goods sold as follows.

Now assume that Morgan requires Lane to sign a note with repayment to be made in 24 monthly payments. Lane is also required to maintain the equipment at a certain level. Morgan sets the payment schedule such that it receives a normal lender's rate of return on the transaction. In addition, Morgan agrees to repurchase the equipment after two years for $95,000.

In this case, this arrangement appears to be a financing transaction rather than a sale. That is, Lane is required to maintain the equipment at a certain level and Morgan agrees to repurchase at a set price, resulting in a lender's return. Thus, the risks and rewards of ownership are to a great extent still with Morgan. When the seller has retained the risks and rewards of ownership, even though legal title has been transferred, the transaction is a financing arrangement and does not give rise to revenue.12 In other words, Morgan has not satisfied its performance obligation.

Bill and Hold Sales

Bill and hold sales result when the buyer is not yet ready to take delivery but does take title and accept billing. For example, a customer may request a company to enter into such an arrangement because of (1) lack of available space for the product, (2) delays in its production schedule, or (3) more than sufficient inventory in its distribution channel.13 Illustration 18-7 provides an example of a bill and hold arrangement.

Butler makes the following entry to record the bill and hold sale.

![]()

If a significant period of time elapses before payment, the accounts receivable is discounted. In addition, it is likely that one of the conditions above is violated (such as the normal payment terms). In this case, the most appropriate approach for bill and hold sales is to defer revenue recognition until the goods are delivered because the risks and rewards of ownership usually do not transfer until that point. [4]

Principal–Agent Relationships

In a principal–agent relationship, amounts collected on behalf of the principal are not revenue of the agent. Instead, revenue for the agent is the amount of the commission it receives (usually a percentage of the total revenue).

Classic Example

An example of principal-agent relationships is an airline that sells tickets through a travel agent. For example, assume that Fly-Away Travels sells airplane tickets for British Airways (BA) to various customers. In this case, the principal is BA and the agent is Fly-Away Travels. BA is acting as a principal because it has exposure to the significant risks and rewards associated with the sale of its services. Fly-Away is acting as an agent because it does not have exposure to significant risks and rewards related to the tickets. Although Fly-Away collects the full airfare from the client, it then remits this amount to BA less a commission. Fly-Away therefore should not record the full amount of the fare as revenue on its books—to do so overstates its revenue. Its revenue is the commission—not the full fare price. The risks and rewards of ownership are not transferred to Fly-Away because it does not bear any inventory risk as it sells tickets to customers.

This distinction is very important for revenue recognition purposes. Some might argue that there is no harm in letting Fly-Away record revenue for the full price of the ticket and then charging the cost of the ticket against the revenue (often referred to as the gross method of recognizing revenue). Others note that this approach overstates the agent's revenue and is misleading. The revenue received is the commission for providing the travel services, not the full fare price (often referred to as the net approach). The profession believes the net approach is the correct method for recognizing revenue in a principal-agent relationship. As a result, the FASB has developed specific criteria to determine when a principal-agent relationship exists.14 An important feature in deciding whether Fly-Away is acting as an agent is whether the amount it earns is predetermined, being either a fixed fee per transaction or a stated percentage of the amount billed to the customer.

What do the numbers mean? GROSSED OUT

As you learned in Chapter 4, many corporate executives obsess over the bottom line. However, analysts on the outside look at the big picture, which includes examination of both the top line and the important subtotals in the income statement, such as gross profit. Recently, the top line is causing some concern, with nearly all companies in the S&P 500 reporting a 2 percent decline in the bottom line while the top line saw revenue decline by 1 percent. This is troubling because it is the first decline in revenues since we crawled out of the recession following the financial crisis. McDonald's gave an ominous preview—it saw its first monthly sales decline in nine years. And the United States, rather than foreign markets, led the drop.

What about income subtotals like gross margin? These metrics too have been under pressure. There is concern that struggling companies may employ a number of manipulations to mask the impact of gross margin declines on the bottom line. In fact, Rite Aid prepares an income statement that omits the gross margin subtotal. That is not surprising when you consider that Rite Aid's gross margin has steadily declined from 28 percent in 2010 to 26 percent in 2012. Rite Aid has used a number of suspect accounting adjustments related to tax allowances and inventory gains to offset its weak gross margin.

Or, consider the classic case of Priceline.com, the company made famous by William Shatner's ads about “naming your own price” for airline tickets and hotel rooms. In one quarter, Priceline reported that it earned $152 million in revenues. But, that included the full amount customers paid for tickets, hotel rooms, and rental cars. Traditional travel agencies call that amount “gross bookings,” not revenues. And, much like regular travel agencies, Priceline keeps only a small portion of gross bookings—namely, the spread between the customers’ accepted bids and the price it paid for the merchandise. The rest, which Priceline calls “product costs,” it pays to the airlines and hotels that supply the tickets and rooms.

However, Priceline's product costs came to $134 million, leaving Priceline just $18 million of what it calls “gross profit” and what most other companies would call revenues. And that's before all of Priceline's other costs—like advertising and salaries—which netted out to a loss of $102 million. The difference isn't academic. Priceline shares traded at about 23 times its reported revenues but at a mind-boggling 214 times its “gross profit.” This and other aggressive recognition practices explains the stricter revenue recognition guidance, indicating that if a company performs as an agent or broker without assuming the risks and rewards of ownership of the goods, the company should report sales on a net (fee) basis.

Sources: Jeremy Kahn, “Presto Chango! Sales Are Huge,” Fortune (March 20, 2000), p. 44; A. Catanach and E. Ketz, “RITE AID: Is Management Selling Drugs or Using Them?” Grumpy Old Accountants (August 22, 2011); and S. Jakab, “Weak Revenue Is New Worry for Investors,” Wall Street Journal (November 25, 2012).

Consignments

Another common principal-agent relationship involves consignments. In these cases, manufacturers (or wholesalers) deliver goods but retain title to the goods until they are sold. This specialized method of marketing certain types of products makes use of a device known as a consignment. Under this arrangement, the consignor (manufacturer or wholesaler) ships merchandise to the consignee (dealer), who is to act as an agent for the consignor in selling the merchandise. Both consignor and consignee are interested in selling—the former to make a profit or develop a market, the latter to make a commission on the sale.

The consignee accepts the merchandise and agrees to exercise due diligence in caring for and selling it. The consignee remits to the consignor cash received from customers, after deducting a sales commission and any chargeable expenses.

In consignment sales, the consignor uses a modified version of the sale basis of revenue recognition. That is, the consignor recognizes revenue only after receiving notification of sale and the cash remittance from the consignee. The consignor carries the merchandise as inventory throughout the consignment, separately classified as Inventory (consignments). The consignee does not record the merchandise as an asset on its books. Upon sale of the merchandise, the consignee has a liability for the net amount due the consignor. The consignor periodically receives from the consignee a report called account sales that shows the merchandise received, merchandise sold, expenses chargeable to the consignment, and the cash remitted. Revenue is then recognized by the consignor. Analysis of a consignment arrangement is provided in Illustration 18-8.

Under the consignment arrangement, the consignor accepts the risk that the merchandise might not sell and relieves the consignee of the need to commit part of its working capital to inventory. Companies use a variety of different systems and account titles to record consignments, but they all share the common goal of postponing the recognition of revenue until it is known that a sale to a third party has occurred.

Trade Loading and Channel Stuffing

One commentator describes trade loading this way: “Trade loading is a crazy, uneconomic, insidious practice through which manufacturers—trying to show sales, profits, and market share they don't actually have—induce their wholesale customers, known as the trade, to buy more product than they can promptly resell.” For example, the cigarette industry appears to have exaggerated a couple years’ operating profits by as much as $600 million by taking the profits from future years.

In the computer software industry, a similar practice is referred to as channel stuffing. When a software maker needed to make its financial results look good, it offered deep discounts to its distributors to overbuy and then recorded revenue when the software left the loading dock. Of course, the distributors’ inventories become bloated and the marketing channel gets too filled with product, but the software maker's current-period financials are improved. However, financial results in future periods will suffer, unless the company repeats the process.

Trade loading and channel stuffing distort operating results and “window dress” financial statements. In addition, similar to consignment transactions or sales with buyback agreements, these arrangements generally do not transfer the risks and rewards of ownership. If used without an appropriate allowance for sales returns, channel stuffing is a classic example of booking tomorrow's revenue today. Business managers need to be aware of the ethical dangers of misleading the financial community by engaging in such practices to improve their financial statements.

What do the numbers mean? NO TAKE-BACKS

Investors in Lucent Technologies were negatively affected when Lucent violated one of the fundamental criteria for revenue recognition—the “no take-back” rule. This rule holds that revenue should not be booked on inventory that is shipped if the customer can return it at some point in the future. In this particular case, Lucent agreed to take back shipped inventory from its distributors if the distributors were unable to sell the items to their customers.

In essence, Lucent was “stuffing the channel.” By booking sales when goods were shipped, even though they most likely would get them back, Lucent was able to report continued sales growth. However, Lucent investors got a nasty surprise when distributors returned those goods and Lucent had to restate its financial results. The restatement erased $679 million in revenues, turning an operating profit into a loss. In response to this bad news, Lucent's share price declined $1.31 per share, or 8.5 percent. Lucent is not alone in this practice. Sunbeam got caught stuffing the sales channel with barbeque grills and other outdoor items, which contributed to its troubles when it was forced to restate its earnings.

Investors can be tipped off to potential channel stuffing by carefully reviewing a company's revenue recognition policy for generous return policies or use of cash incentives to encourage distributors to buy products (as was done at Monsanto) and by watching inventory and receivables levels. When sales increase along with receivables, that's one sign that customers are not paying for goods shipped on credit. And growing inventory levels are an indicator that customers have all the goods they need. Both scenarios suggest a higher likelihood of goods being returned and revenues and income being restated. So remember, no take-backs!

Sources: Adapted from S. Young, “Lucent Slashes First Quarter Outlook, Erases Revenue from Latest Quarter,” Wall Street Journal Online (December 22, 2000); Tracey Byrnes, “Too Many Thin Mints: Spotting the Practice of Channel Stuffing,” Wall Street Journal Online (February 7, 2002); and H. Weitzman, “Monsanto to Restate Results After SEC Probe,” Financial Times (October 5, 2011).

Multiple-Deliverable Arrangements

One of the most difficult issues related to revenue recognition involves multiple-deliverable arrangements (MDAs). MDAs provide multiple products or services to customers as part of a single arrangement. The major accounting issues related to this type of arrangement are how to allocate the revenue to the various products and services and how to allocate the revenue to the proper period.

These issues are particularly complex in the technology area. Many devices have contracts that typically include such multiple deliverables as hardware, software, professional services, maintenance, and support—all of which are valued and accounted for differently. A classic example relates to the Apple iPhone and its AppleTV product. Basically, until a recent rule change, revenues and related costs were accounted for on a subscription basis over a period of years. The reason was that Apple provides future unspecified software upgrades and other features without charge. It was argued that Apple should defer a significant portion of the cash received for the iPhone and recognize it over future periods. At the same time, engineering, marketing, and warranty costs were expensed as incurred. As a result, Apple reported conservative numbers related to its iPhone revenue. However, as a result of efforts to more clearly define the various services related to an item such as the iPhone, Apple is now able to report more revenue at the point of sale.

In general, all units in a multiple-deliverable arrangement are considered separate units of accounting, provided that:

- A delivered item has value to the customer on a standalone basis; and

- The arrangement includes a general right of return relative to the delivered item; and

- Delivery or performance of the undelivered item is considered probable and substantially in the control of the seller.

Once the separate units of accounting are determined, the amount paid for the arrangement is allocated among the separate units based on relative fair value. A company determines fair value based on what the vendor could sell the component for on a standalone basis. If this information is not available, the seller may rely on third-party evidence or if not available, the seller may use its best estimate of what the item might sell for as a standalone unit. [6] Illustration 18-9 identifies the steps in the evaluation process.

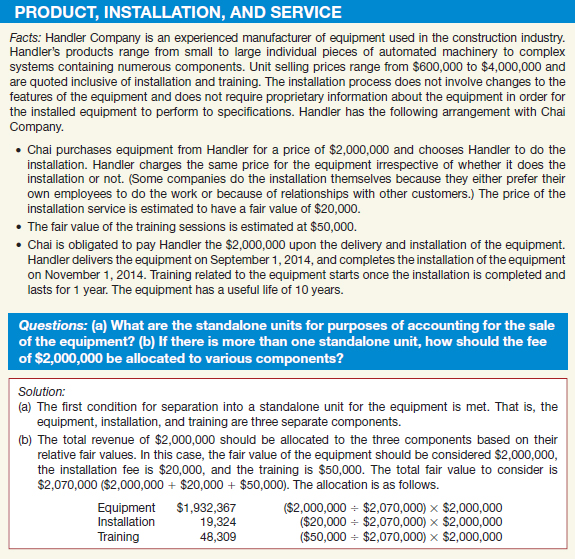

Presented in Illustrations 18-10 and 18-11 are two examples of the accounting for MDAs.

Handler makes the following entries on November 1, 2014.

The sale of the equipment should be recognized once the installation is completed on November 1, 2014, and the installation fee also should be recognized because these services have been provided. The training revenues should be allocated on a straight-line basis starting on November 1, 2014, or $4,026 ($48,309 ÷ 12) per month for one year (unless a more appropriate method such as the percentage-of-completion method is warranted). The journal entry to recognize the training revenue for two months in 2014 is as follows.

![]()

Therefore, the total revenue recognized at December 31, 2014, is $1,959,743 ($1,932,367 + $19,324 + $8,052). Handler makes the following journal entry to recognize the training revenue in 2015, assuming adjusting entries are made at year-end.

![]()

Summary

Illustration 18-12 provides a summary of revenue recognition methods and related accounting guidance.

REVENUE RECOGNITION BEFORE DELIVERY

For the most part, companies recognize revenue at the point of sale (delivery) because at point of sale most of the uncertainties in the earning process are removed and the exchange price is known. Under certain circumstances, however, companies recognize revenue prior to completion and delivery. The most notable example is long-term construction contract accounting, which uses the percentage-of-completion method.

Long-term contracts frequently provide that the seller (builder) may bill the purchaser at intervals, as it reaches various points in the project. Examples of long-term contracts are construction-type contracts, development of military and commercial aircraft, weapons-delivery systems, and space exploration hardware. When the project consists of separable units, such as a group of buildings or miles of roadway, contract provisions may provide for delivery in installments. In that case, the seller would bill the buyer and transfer title at stated stages of completion, such as the completion of each building unit or every 10 miles of road. The accounting records should record sales when installments are “delivered.”15

Two distinctly different methods of accounting for long-term construction contracts are recognized.16 They are:

- Percentage-of-completion method. Companies recognize revenues and gross profits each period based upon the progress of the construction—that is, the percentage of completion. The company accumulates construction costs plus gross profit earned to date in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Process).

- Completed-contract method. Companies recognize revenues and gross profit only when the contract is completed. The company accumulates construction costs in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Process).

The rationale for using percentage-of-completion accounting is that under most of these contracts the buyer and seller have enforceable rights. The buyer has the legal right to require specific performance on the contract. The seller has the right to require progress payments that provide evidence of the buyer's ownership interest. As a result, a continuous sale occurs as the work progresses. Companies should recognize revenue according to that progression.

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

The percentage-of-completion method recognizes revenue from long-term contracts in the periods in which the revenue is earned. The firm contract fixes the selling price. And, if costs are estimable and collection reasonably assured, the revenue recognition concept is not violated.

Companies must use the percentage-of-completion method when estimates of progress toward completion, revenues, and costs are reasonably dependable and all of the following conditions exist. [7]

- The contract clearly specifies the enforceable rights regarding goods or services to be provided and received by the parties, the consideration to be exchanged, and the manner and terms of settlement.

- The buyer can be expected to satisfy all obligations under the contract.

- The contractor can be expected to perform the contractual obligations.

Companies should use the completed-contract method when one of the following conditions applies:

- When a company has primarily short-term contracts, or

- When a company cannot meet the conditions for using the percentage-of-completion method, or

- When there are inherent hazards in the contract beyond the normal, recurring business risks.

The presumption is that percentage-of-completion is the better method. Therefore, companies should use the completed-contract method only when the percentage-of-completion method is inappropriate. We discuss the two methods in more detail in the following sections.

Percentage-of-Completion Method

The percentage-of-completion method recognizes revenues, costs, and gross profit as a company makes progress toward completion on a long-term contract. To defer recognition of these items until completion of the entire contract is to misrepresent the efforts (costs) and accomplishments (revenues) of the accounting periods during the contract. In order to apply the percentage-of-completion method, a company must have some basis or standard for measuring the progress toward completion at particular interim dates.

Measuring the Progress toward Completion

As one practicing accountant wrote, “The big problem in applying the percentage-of-completion method … has to do with the ability to make reasonably accurate estimates of completion and the final gross profit.”17 Companies use various methods to determine the extent of progress toward completion. The most common are the cost-to-cost and units-of-delivery methods.18

The objective of all these methods is to measure the extent of progress in terms of costs, units, or value added. Companies identify the various measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked, tons produced, floors completed, etc.) and classify them as input or output measures. Input measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked) are efforts devoted to a contract. Output measures (with units of delivery measured as tons produced, floors of a building completed, miles of a highway completed) track results. Neither are universally applicable to all long-term projects. Their use requires the exercise of judgment and careful tailoring to the circumstances.

Both input and output measures have certain disadvantages. The input measure is based on an established relationship between a unit of input and productivity. If inefficiencies cause the productivity relationship to change, inaccurate measurements result. Another potential problem is front-end loading, in which significant up-front costs result in higher estimates of completion. To avoid this problem, companies should disregard some early-stage construction costs—for example, costs of uninstalled materials or costs of subcontracts not yet performed—if they do not relate to contract performance.

Similarly, output measures can produce inaccurate results if the units used are not comparable in time, effort, or cost to complete. For example, using floors (stories) completed can be deceiving. Completing the first floor of an eight-story building may require more than one-eighth the total cost because of the substructure and foundation construction.

The most popular input measure used to determine the progress toward completion is the cost-to-cost basis. Under this basis, a company like EDS measures the percentage of completion by comparing costs incurred to date with the most recent estimate of the total costs required to complete the contract. Illustration 18-13 shows the formula for the cost-to-cost basis.

Once EDS knows the percentage that costs incurred bear to total estimated costs, it applies that percentage to the total revenue or the estimated total gross profit on the contract. The resulting amount is the revenue or the gross profit to be recognized to date. Illustration 18-14 shows this computation.

To find the amounts of revenue and gross profit recognized each period, EDS subtracts total revenue or gross profit recognized in prior periods, as shown in Illustration 18-15.

Because the cost-to-cost method is widely used (without excluding other bases for measuring progress toward completion), we have adopted it for use in our examples. [8]

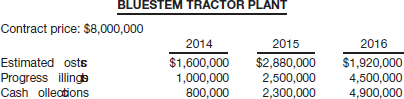

Example of Percentage-of-Completion Method—Cost-to-Cost Basis

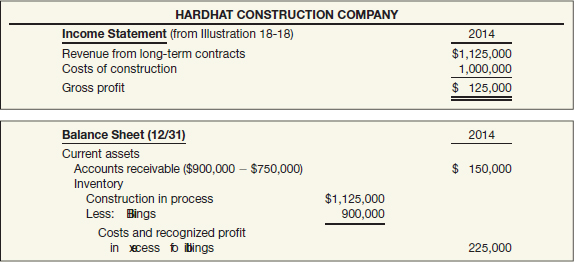

To illustrate the percentage-of-completion method, assume that Hardhat Construction Company has a contract to construct a $4,500,000 bridge at an estimated cost of $4,000,000. The contract is to start in July 2014, and the bridge is to be completed in October 2016. The following data pertain to the construction period. (Note that by the end of 2015, Hardhat has revised the estimated total cost from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000.)

Hardhat would compute the percentage complete as shown in Illustration 18-16.

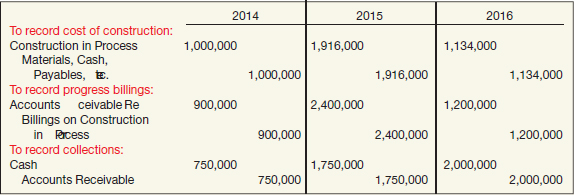

On the basis of the data above, Hardhat would make the following entries to record (1) the costs of construction, (2) progress billings, and (3) collections. These entries appear as summaries of the many transactions that would be entered individually as they occur during the year.

In this example, the costs incurred to date are a measure of the extent of progress toward completion. To determine this, Hardhat evaluates the costs incurred to date as a proportion of the estimated total costs to be incurred on the project. The estimated revenue and gross profit that Hardhat will recognize for each year are calculated as shown in Illustration 18-18.

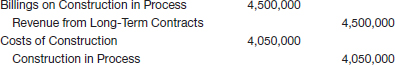

Illustration 18-19 shows Hardhat's entries to recognize revenue and gross profit each year and to record completion and final approval of the contract.

ILLUSTRATION 18-19 Journal Entries to Recognize Revenue and Gross Profit and to Record Contract Completion—Percentage-of-Completion Method, Cost-to-Cost Basis

Note that Hardhat debits gross profit (as computed in Illustration 18-18) to Construction in Process. Similarly, it credits Revenue from Long-Term Contracts for the amounts computed in Illustration 18-18. Hardhat then debits the difference between the amounts recognized each year for revenue and gross profit to a nominal account, Construction Expenses (similar to Cost of Goods Sold in a manufacturing company). It reports that amount in the income statement as the actual cost of construction incurred in that period. For example, Hardhat uses the actual costs of $1,000,000 to compute both the gross profit of $125,000 and the percent complete (25 percent).

Hardhat continues to accumulate costs in the Construction in Process account, in order to maintain a record of total costs incurred (plus recognized gross profit) to date. Although theoretically a series of “sales” takes place using the percentage-of-completion method, the selling company cannot remove the inventory cost until the construction is completed and transferred to the new owner. Hardhat's Construction in Process account for the bridge would include the following summarized entries over the term of the construction project.

Recall that the Hardhat Construction Company example contained a change in estimate: In the second year, 2015, it increased the estimated total costs from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000. The change in estimate is accounted for in a cumulative catch-up manner. This is done by first adjusting the percent completed to the new estimate of total costs. Next, Hardhat deducts the amount of revenues and gross profit recognized in prior periods from revenues and gross profit computed for progress to date. That is, it accounts for the change in estimate in the period of change. That way, the balance sheet at the end of the period of change and the accounting in subsequent periods are as they would have been if the revised estimate had been the original estimate.

Financial Statement Presentation—Percentage-of-Completion

Generally, when a company records a receivable from a sale, it reduces the Inventory account. Under the percentage-of-completion method, however, the company continues to carry both the receivable and the inventory. Subtracting the balance in the Billings account from Construction in Process avoids double-counting the inventory. During the life of the contract, Hardhat reports in the balance sheet the difference between the Construction in Process and the Billings on Construction in Process accounts. If that amount is a debit, Hardhat reports it as a current asset; if it is a credit, it reports it as a current liability.

At times, the costs incurred plus the gross profit recognized to date (the balance in Construction in Process) exceed the billings. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current asset entitled “Cost and recognized profit in excess of billings.” Hardhat can at any time calculate the unbilled portion of revenue recognized to date by subtracting the billings to date from the revenue recognized to date, as illustrated for 2014 for Hardhat Construction in Illustration 18-21.

At other times, the billings exceed costs incurred and gross profit to date. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current liability entitled “Billings in excess of costs and recognized profit.”

It probably has occurred to you that companies often have more than one project going at a time. When a company has a number of projects, costs exceed billings on some contracts and billings exceed costs on others. In such a case, the company segregates the contracts. The asset side includes only those contracts on which costs and recognized profit exceed billings. The liability side includes only those on which billings exceed costs and recognized profit. Separate disclosures of the dollar volume of billings and costs are preferable to a summary presentation of the net difference.

Using data from the bridge example, Hardhat Construction Company would report the status and results of its long-term construction activities under the percentage-of-completion method as shown in Illustration 18-22.

In 2015, its financial statement presentation is as follows.

In 2016, Hardhat's financial statements only include an income statement because the bridge project was completed and settled.

In addition, Hardhat should disclose the following information in each year.

Completed-Contract Method

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Apply the completed-contract method for long-term contracts.

Under the completed-contract method, companies recognize revenue and gross profit only at point of sale—that is, when the contract is completed. Under this method, companies accumulate costs of long-term contracts in process, but they make no interim charges or credits to income statement accounts for revenues, costs, or gross profit.

![]() International Perspective

International Perspective

IFRS prohibits the use of the completed-contract method of accounting for long-term construction contracts. Companies must use the percentage-of-completion method. If revenues and costs are difficult to estimate, then companies recognize revenue only to the extent of the cost incurred—a zero-profit approach.

The principal advantage of the completed-contract method is that reported revenue reflects final results rather than estimates of unperformed work. Its major disadvantage is that it does not reflect current performance when the period of a contract extends into more than one accounting period. Although operations may be fairly uniform during the period of the contract, the company will not report revenue until the year of completion, creating a distortion of earnings.

Under the completed-contract method, the company would make the same annual entries to record costs of construction, progress billings, and collections from customers as those illustrated under the percentage-of-completion method. The significant difference is that the company would not make entries to recognize revenue and gross profit.

For example, under the completed-contract method for the bridge project illustrated on the preceding pages, Hardhat Construction Company would make the following entries in 2016 to recognize revenue and costs and to close out the inventory and billing accounts.

Illustration 18-26 compares the amount of gross profit that Hardhat Construction Company would recognize for the bridge project under the two revenue recognition methods.

Under the completed-contract method, Hardhat Construction would report its long-term construction activities as follows.

Long-Term Contract Losses

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Identify the proper accounting for losses on long-term contracts.

Two types of losses can become evident under long-term contracts:19

- Loss in the current period on a profitable contract. This condition arises when, during construction, there is a significant increase in the estimated total contract costs but the increase does not eliminate all profit on the contract. Under the percentage-of-completion method only, the estimated cost increase requires a current-period adjustment of excess gross profit recognized on the project in prior periods. The company records this adjustment as a loss in the current period because it is a change in accounting estimate (discussed in Chapter 22).

- Loss on an unprofitable contract. Cost estimates at the end of the current period may indicate that a loss will result on completion of the entire contract. Under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the company must recognize in the current period the entire expected contract loss.

The treatment described for unprofitable contracts is consistent with the accounting custom of anticipating foreseeable losses to avoid overstatement of current and future income (conservatism).

Loss in Current Period

To illustrate a loss in the current period on a contract expected to be profitable upon completion, we'll continue with the Hardhat Construction Company bridge project. Assume that on December 31, 2015, Hardhat estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1,468,962 instead of $1,134,000 (refer to page 1059). Assuming all other data are the same as before, Hardhat would compute the percentage complete and recognize the loss as shown in Illustration 18-28. Compare these computations with those for 2015 in Illustration 18-16 (page 1059). The “percent complete” has dropped, from 72 percent to 66½ percent, due to the increase in estimated future costs to complete the contract.

The 2015 loss of $48,500 is a cumulative adjustment of the “excessive” gross profit recognized on the contract in 2014. Instead of restating the prior period, the company absorbs the prior period misstatement entirely in the current period. In this illustration, the adjustment was large enough to result in recognition of a loss.

Hardhat Construction would record the loss in 2015 as follows.

![]()

Hardhat will report the loss of $48,500 on the 2015 income statement as the difference between the reported revenues of $1,867,500 and the costs of $1,916,000.20 Under the completed-contract method, the company does not recognize a loss in 2015. Why not? Because the company still expects the contract to result in a profit, to be recognized in the year of completion.

Loss on an Unprofitable Contract

To illustrate the accounting for an overall loss on a long-term contract, assume that at December 31, 2015, Hardhat Construction Company estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1,640,250 instead of $1,134,000. Revised estimates for the bridge contract are as follows.

Under the percentage-of-completion method, Hardhat recognized $125,000 of gross profit in 2014 (see Illustration 18-18 on page 1060). This amount must be offset in 2015 because it is no longer expected to be realized. In addition, since losses must be recognized as soon as estimable, the company must recognize the total estimated loss of $56,250 in 2015. Therefore, Hardhat must recognize a total loss of $181,250 ($125,000 + $56,250) in 2015.

Illustration 18-29 shows Hardhat's computation of the revenue to be recognized in 2015.

To compute the construction costs to be expensed in 2015, Hardhat adds the total loss to be recognized in 2015 ($125,000 + $56,250) to the revenue to be recognized in 2015. Illustration 18-30 shows this computation.

Hardhat Construction would record the long-term contract revenues, expenses, and loss in 2015 as follows.

![]()

At the end of 2015, Construction in Process has a balance of $2,859,750 as shown below.21

Under the completed-contract method, Hardhat also would recognize the contract loss of $56,250 through the following entry in 2015 (the year in which the loss first became evident).

![]()

Just as the Billings account balance cannot exceed the contract price, neither can the balance in Construction in Process exceed the contract price. In circumstances where the Construction in Process balance exceeds the billings, the company can deduct the recognized loss from such accumulated costs on the balance sheet. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the provision for the loss (the credit) may be combined with Construction in Process, thereby reducing the inventory balance. In those circumstances, however (as in the 2015 example above), where the billings exceed the accumulated costs, Hardhat must report separately on the balance sheet, as a current liability, the amount of the estimated loss. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, Hardhat would take the $56,250 loss, as estimated in 2015, from the Construction in Process account and report it separately as a current liability titled “Estimated liability from long-term contracts.” [9]

What do the numbers mean? LESS CONSERVATIVE

Halliburton provides engineering- and construction-related services in jobs around the world. Much of the company's work is completed under contract over long periods of time. The company uses percentage-of-completion accounting. The SEC started enforcement proceedings against the company related to its accounting for contract claims and disagreements with customers, including those arising from change orders and disputes about billable amounts and costs associated with a construction delay.

Prior to 1998, Halliburton took a very conservative approach to its accounting for disputed claims. As stated in the company's 1997 annual report, “Claims for additional compensation are recognized during the period such claims are resolved.” That is, the company waited until all disputes were resolved before recognizing associated revenues. In contrast, in 1998 the company recognized revenue for disputed claims before their resolution, using estimates of amounts expected to be recovered. Such revenue and its related profit are more tentative and are subject to possible later adjustment than revenue and profit recognized when all claims have been resolved. As a case in point, the company noted that it incurred losses of $99 million in 1998 related to customer claims.

The accounting method put in place in 1998 is more aggressive than the company's former policy, but it is still within the boundaries of generally accepted accounting principles. However, the SEC noted that over six quarters, Halliburton failed to disclose its change in accounting practice. In the absence of any disclosure, the SEC believed the investing public was misled about the precise nature of Halliburton's income in comparison to prior periods.

Similar issues have arisen in how Boeing accounts for losses on its Dreamliner aircraft long-term contracts. While costs for producing the first group of airplanes more than doubled in a recent year, the losses did not show up in Boeing's bottom line. The reason? Boeing is spreading the higher cost over future years when it expects costs to decline and profit margins to increase. Boeing recently increased the number of planes over which future cost will be spread from 400 to 1,100 due to increased demand for the planes, which further reduces the impact on profitability. The Halliburton and Boeing situations illustrate the difficulty of using estimates in percentage-of-completion accounting and the impact of those estimates on the financial statements.

Sources: “Failure to Disclose a 1998 Change in Accounting Practice,” SEC (August 3, 2004), www.sec.gov/news/press/2004-104.htm. See also “Accounting Ace Charles Mulford Answers Accounting Questions,” Wall Street Journal Online (June 7, 2002); and J. Ostrower, “Dreamliner Hits a Milestone,” Wall Street Journal (June 8, 2012).

Disclosures in Financial Statements

Construction contractors usually make some unique financial statement disclosures in addition to those required of all businesses. Generally, these additional disclosures are made in the notes to the financial statements. For example, a construction contractor should disclose the following: the method of recognizing revenue, [10] the basis used to classify assets and liabilities as current (the nature and length of the operating cycle), the basis for recording inventory, the effects of any revision of estimates, the amount of backlog on uncompleted contracts, and the details about receivables (billed and unbilled, maturity, interest rates, retainage provisions, and significant individual or group concentrations of credit risk).

Completion-of-Production Basis

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

This is not an exception to the revenue recognition principle. At the completion of production, realization is virtually assured and the earning process is substantially completed.

In certain cases, companies recognize revenue at the completion of production even though no sale has been made. Examples of such situations involve precious metals or agricultural products with assured prices. Under the completion-of-production basis, companies recognize revenue when these metals are mined or agricultural crops harvested because the sales price is reasonably assured, the units are interchangeable, and no significant costs are involved in distributing the product.22 (See discussion in Chapter 9, page 481, “Valuation at Net Realizable Value.”)

Likewise, when sale or cash receipt precedes production and delivery, as in the case of magazine subscriptions, companies recognize revenues as earned by production and delivery.23

REVENUE RECOGNITION AFTER DELIVERY

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe the installment-sales method of accounting.

In some cases, the collection of the sales price is not reasonably assured and revenue recognition is deferred. One of two methods is generally employed to defer revenue recognition until the company receives cash: the installment-sales method or the cost-recovery method. A third method, the deposit method, applies in situations in which a company receives cash prior to delivery or transfer of the property; the company records that receipt as a deposit because the sales transaction is incomplete. This section examines these three methods.

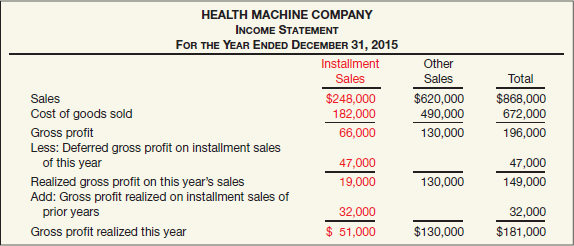

Installment-Sales Method

The installment-sales method recognizes income in the periods of collection rather than in the period of sale. The logic underlying this method is that when there is no reasonable approach for estimating the degree of collectibility, companies should not recognize revenue until cash is collected.

The expression “installment sales” generally describes any type of sale for which payment is required in periodic installments over an extended period of time. All types of farm and home equipment as well as home furnishings are sold on an installment basis. The heavy equipment industry also sometimes uses the method for machine installations paid for over a long period. Another application of the method is in land-development sales.

![]() Underlying Concepts

Underlying Concepts

Realization is a critical part of revenue recognition. Thus, if a high degree of uncertainty exists about collectibility, a company must defer revenue recognition.

Because payment is spread over a relatively long period, the risk of loss resulting from uncollectible accounts is greater in installment-sales transactions than in ordinary sales. Consequently, selling companies use various devices to protect themselves. Two common devices are (1) the use of a conditional sales contract, which specifies that title to the item sold does not pass to the purchaser until all payments are made, and (2) use of notes secured by a chattel (personal property) mortgage on the article sold. Either of these permits the seller to “repossess” the goods sold if the purchaser defaults on one or more payments. The seller can then resell the repossessed merchandise at whatever price it will bring to compensate for the uncollected installments and the expense of repossession.

Under the installment-sales method of accounting, companies defer income recognition until the period of cash collection. They recognize both revenues and costs of sales in the period of sale, but defer the related gross profit to those periods in which they collect the cash. Thus, instead of deferring the sale, along with related costs and expenses, to the future periods of anticipated collection, the company defers only the proportional gross profit. This approach is equivalent to deferring both sales and cost of sales. Other expenses—that is, selling expense, administrative expense, and so on—are not deferred.

Thus, the installment-sales method matches cost and expenses against sales through the gross profit figure, but no further. Companies using the installment-sales method generally record operating expenses without regard to the fact that they will defer some portion of the year's gross profit. This practice is often justified on the basis that (1) these expenses do not follow sales as closely as does the cost of goods sold, and (2) accurate apportionment among periods would be so difficult that it could not be justified by the benefits gained.24

Acceptability of the Installment-Sales Method

The use of the installment-sales method for revenue recognition has fluctuated widely. At one time, it was widely accepted for installment-sales transactions. Somewhat paradoxically, as installment-sales transactions increased in popularity, acceptance and use of the installment-sales method decreased. Finally, the profession concluded that except in special circumstances, “the installment method of recognizing revenue is not acceptable.” [11] The rationale for this position is simple. Because the installment method recognizes no income until cash is collected, it is not in accordance with the accrual-accounting concept.

Use of the installment-sales method was often justified on the grounds that the risk of not collecting an account receivable may be so great that the sale itself is not sufficient evidence that recognition should occur. In some cases, this reasoning is valid but not in a majority of cases. The general approach is that a company should recognize a completed sale. If the company expects bad debts, it should record this possibility as separate estimates of uncollectibles. Although collection expenses, repossession expenses, and bad debts are an unavoidable part of installment-sales activities, the incurrence of these costs and the collectibility of the receivables are reasonably predictable.

We study this topic in intermediate accounting because the method is acceptable in cases where a company believes there to be no reasonable basis of estimating the degree of collectibility. In addition, the sales method of revenue recognition has certain weaknesses when used for franchise and land-development operations. Application of the sales method to franchise and license operations has resulted in the abuse described earlier as “front-end loading.” In some cases, franchisors recognized revenue prematurely, when they granted a franchise or issued a license, rather than when revenue was earned or the cash is received. Many land-development ventures were susceptible to the same abuses. As a result, the FASB prescribes application of the installment-sales method of accounting for sales of real estate under certain circumstances. [12]25

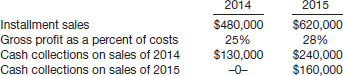

Procedure for Deferring Revenue and Cost of Sales of Merchandise

One could work out a procedure that deferred both the uncollected portion of the sales price and the proportionate part of the cost of the goods sold. Instead of apportioning both sales price and cost over the period of collection, however, the installment-sales method defers only the gross profit. This procedure has exactly the same effect as deferring both sales and cost of sales, but it requires only one deferred account rather than two.

For the sales in any one year, the steps companies use to defer gross profit are as follows.

- During the year, record both sales and cost of sales in the regular way, using the special accounts described later, and compute the rate of gross profit on installment-sales transactions.

- At the end of the year, apply the rate of gross profit to the cash collections of the current year's installment sales, to arrive at the realized gross profit.

- Defer to future years the gross profit not realized.

For sales made in prior years, companies apply the gross profit rate of each year's sales against cash collections of accounts receivable resulting from that year's sales, to arrive at the realized gross profit.

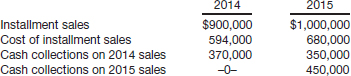

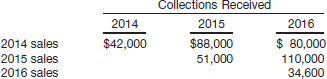

Special accounts must be used in the installment-sales method. These accounts provide certain information required to determine the realized and unrealized gross profit in each year of operations. In computing net income under the installment-sales method as generally applied, the only peculiarity is the deferral of gross profit until realized by accounts receivable collection. We will use the following data to illustrate the installment-sales method in accounting for the sales of merchandise.

To simplify this example, we have excluded interest charges. Summary entries in general journal form for the year 2014 are as follows.

Illustration 18-32 shows computation of the realized and deferred gross profit for the year 2014.

Summary entries in journal form for year 2 (2015) are as follows.

Illustration 18-33 shows computation of the realized and deferred gross profit for the year 2015.

The entries in 2016 would be similar to those of 2015, and the total gross profit taken up or realized would be $64,000, as shown by the computations in Illustration 18-34.

In summary, here are the basic concepts you should understand about accounting for installment sales:

- How to compute a proper gross profit percentage.

- How to record installment sales, cost of installment sales, and deferred gross profit.

- How to compute realized gross profit on installment receivables.

- How the deferred gross profit balance at the end of the year results from applying the gross profit rate to the installment accounts receivable.

Additional Problems of Installment-Sales Accounting

In addition to computing realized and deferred gross profit currently, other problems are involved in accounting for installment-sales transactions. These problems are related to:

- Interest on installment contracts.

- Uncollectible accounts.

- Defaults and repossessions.

Interest on Installment Contracts. Because the collection of installment receivables is spread over a long period, it is customary to charge the buyer interest on the unpaid balance. The seller and buyer set up a schedule of equal payments consisting of interest and principal. Each successive payment is attributable to a smaller amount of interest and a correspondingly larger amount of principal, as shown in Illustration 18-35. This illustration assumes that a company sells for $3,000 an asset costing $2,400 (rate of gross profit = 20%), with interest of 8 percent included in the three installments of $1,164.10.

The company accounts for interest separate from the gross profit recognized on the installment-sales collections during the period, by recognizing interest revenue at the time of its cash receipt.

Uncollectible Accounts. The problem of bad debts or uncollectible accounts receivable is somewhat different for concerns selling on an installment basis because of a repossession feature commonly incorporated in the sales agreement. This feature gives the selling company an opportunity to recoup an uncollectible account through repossession and resale of repossessed merchandise. If the experience of the company indicates that repossessions do not, as a rule, compensate for uncollectible balances, it may be advisable to provide for such losses through charges to a special bad debt expense account, just as is done for other credit sales.

Defaults and Repossessions. Depending on the terms of the sales contract and the policy of the credit department, the seller can repossess merchandise sold under an installment arrangement if the purchaser fails to meet payment requirements. The seller may then recondition repossessed merchandise before offering it for resale, for either cash or installment payments.

The accounting for repossessions recognizes that the company is not likely to collect the related installment receivable and should write it off. Along with the installment account receivable, the company must remove the applicable deferred gross profit using the following entry.

![]()

This entry assumes that the company will record the repossessed merchandise at exactly the amount of the uncollected account less the deferred gross profit applicable. This assumption may or may not be proper. To determine the correct amount, the company should consider the condition of the repossessed merchandise, the cost of reconditioning, and the market for secondhand merchandise of that particular type. The objective should be to put any asset acquired on the books at its fair value, or at the best possible approximation of fair value when fair value is not determinable. A loss can occur if the fair value of the repossessed merchandise is less than the uncollected balance less the deferred gross profit. In that case, the company should record a “loss on repossession” at the date of repossession.26

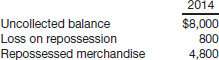

To illustrate the required entry, assume that Klein Brothers sells a refrigerator to Marilyn Hunt for $1,500 on September 1, 2014. Terms require a down payment of $600 and $60 on the first of every month for 15 months, starting October 1, 2014. It is further assumed that the refrigerator cost $900 and that Klein Brothers priced it to provide a 40 percent rate of gross profit on selling price. At the year-end, December 31, 2014, Klein Brothers should have collected a total of $180 in addition to the original down payment.

If Hunt makes her January and February payments in 2015 and then defaults, the account balances applicable to Hunt at time of default are as shown in Illustration 18-36.

As indicated, Klein Brothers compute the balance of deferred gross profit applicable to Hunt's account by applying the gross profit rate for the year of sale to the balance of Hunt's account receivable: 40 percent of $600, or $240. The account balances are therefore:

![]()

Klein repossesses the refrigerator following Hunt's default. If Klein sets the estimated fair value of the repossessed article at $150, it would make the following entry to record the repossession.