We’ve coded most of the page, and you now know most of what there is to know about new HTML5 elements and their semantics. But before we start work on the look of the site—which we do in Chapter 6—we’ll take a quick detour away from The HTML5 Herald’s front page to have a look at the sign-up page. This will illustrate what HTML5 has to offer in terms of web forms.

HTML5 web forms have introduced new form elements, input types, attributes, and other features. Many of these features we’ve been using in our interfaces for years: form validation, combo boxes, placeholder text, and the like. The difference is that where before we had to resort to JavaScript to create these behaviors, they’re now available directly in the browser; all you need to do is set an attribute in your markup to make them available.

HTML5 not only makes marking up forms easier on the developer, it’s also better for the user. With client-side validation being handled natively by the browser, there will be greater consistency across different sites, and many pages will load faster without all that redundant JavaScript.

Let’s dive in!

Forms are often the last thing developers include in their pages—many developers find forms just plain boring. The good news is that HTML5 injects a little bit more joy into coding forms. By the end of this chapter, we hope you’ll look forward to employing form elements, as appropriate, in your markup.

Let’s start off our sign-up form with plain, old-fashioned HTML:

<form id="register" method="post">

<hgroup>

<h1>Sign Me Up!</h1>

<h2>I would like to receive your fine publication.</h2>

</hgroup>

<ul>

<li>

<label for="register-name">My name is:</label>

<input type="text" id="register-name" name="name">

</li>

<li>

<label for="address">My email address is:</label>

<input type="text" id="address" name="address">

</li>

<li>

<label for="url">My website is located at:</label>

<input type="text" id="url" name="url">

</li>

<li>

<label for="password">I would like my password to be:</label>

<p>(at least 6 characters, no spaces)</p>

<input type="password" id="password" name="password">

</li>

<li>

<label for="rating">On a scale of 1 to 10, my knowledge of

↵HTML5 is:</label>

<input type="text" name="rating" id=rating">

</li>

<li>

<label for="startdate">Please start my subscription on:

↵</label>

<input type="text" id="startdate" name="startdate">

</li>

<li>

<label for="quantity">I would like to receive <input

↵type="text" name="quantity" id="quantity"> copies of <cite>

↵The HTML5 Herald</cite>.</label>

</li>

<li>

<label for="upsell">Also sign me up for <cite>The CSS3

↵Chronicle</cite></label>

<input type="checkbox" id="upsell" name="upsell">

</li>

<li>

<input type="submit" id="register-submit" value="Send Post

↵Haste">

</li>

</ul>

</form>

This sample registration form uses form elements that have been

available since the earliest versions of HTML. This form provides clues to

users about what type of data is expected in each field via the label and p

elements, so even your users on Netscape 4.7 and IE5 (kidding!) can

understand the form. It works, but it can certainly be improved

upon.

In this chapter we’re going to enhance this form to include HTML5’s features. HTML5 provides new input types specific to email addresses, URLs, numbers, dates, and more. In addition to those new input types, HTML5 also introduces attributes that can be used with both new and existent input types. These allow you to provide placeholder text, mark fields as required, and declare what type of data is acceptable—all without JavaScript.

We’ll cover all the newly added input types later in the chapter. Before we do that, let’s take a look at the new form attributes HTML5 provides.

For years, developers have written (or copied and pasted) snippets of JavaScript to validate the information users entered into form fields: what elements are required, what type of data is accepted, and so on. HTML5 provides us with several attributes that allow us to dictate what is an acceptable value, and inform the user of errors, all without the use of any JavaScript.

Browsers that support these HTML5 attributes will compare data entered by the user against regular expression patterns provided by the developer (you). Then they check to see if all required fields are indeed filled out, enable multiple values if allowed, and so on. Even better, including these attributes won’t harm older browsers; they’ll simply ignore the attributes they don’t understand. In fact, you can use these attributes and their values to power your scripting fallbacks, instead of hardcoding validation patterns into your JavaScript code, or adding superfluous classes to your markup. We’ll look at how this is done a bit later; for now, let’s go through each of the new attributes.

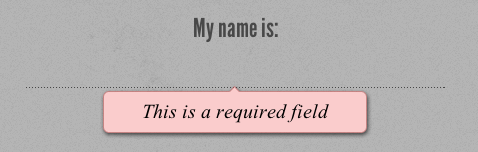

The Boolean required

attribute tells the browser to only submit the form if the field in

question is filled out correctly. Obviously, this means that the field

can’t be left empty, but it also means that, depending on other

attributes or the field’s type, only certain types of values will be

accepted. Later in the chapter, we’ll be covering different ways of

letting browsers know what kind of data is expected in a form.

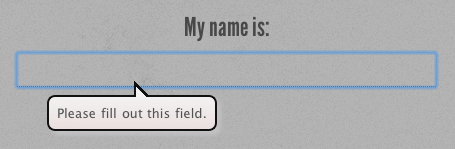

If a required field is empty or invalid, the form will fail to submit, and focus will move to the first invalid form element. Opera, Firefox, and Chrome provide the user with error messages; for example, “Please fill out this field” or “You have to specify a value” if left empty, and “Please enter an email address” or “xyz is not in the format this page requires” when the data type or pattern is wrong.

Note: Out of focus?

Time for a quick refresher: a form element is

focused either when a user clicks on the field

with their mouse, or tabs to it with their keyboard. For input elements, typing with the keyboard

will enter data into that element.

In

JavaScript terminology, the focus event

will fire on a form element when it receives focus, and the

blur event will fire when it loses

focus.

In CSS, the :focus pseudo-class can be used

to style elements that currently have focus.

The required attribute can be

set on any input type except

button,

range,

color, and

hidden, all of which generally have a

default value. As with other Boolean attributes we’ve seen so far, the

syntax is either simply required, or

required="required" if you’re using XHTML

syntax.

Let’s add the required

attribute to our sign-up form. We’ll make the name, email address,

password, and subscription start date fields required:

<ul>

<li>

<label for="register-name">My name is:</label>

<input type="text" id="register-name" name="name"

↵required aria-required="true">

</li>

<li>

<label for="email">My email address is:</label>

<input type="text" id="email" name="email"

↵required aria-required="true">

</li>

<li>

<label for="url">My website is located at:</label>

<input type="text" id="url" name="url">

</li>

<li>

<label for="password">I would like my password to be:</label>

<p>(at least 6 characters, no spaces)</p>

<input type="password" id="password" name="password"

↵required aria-required="true">

</li>

<li>

<label for="rating">On a scale of 1 to 10, my knowledge of

↵HTML5 is:</label>

<input type="text" name="rating" type="range">

</li>

<li>

<label for="startdate">Please start my subscription on:

↵</label>

<input type="text" id="startdate" name="startdate"

↵required aria-required="true">

</li>

<li>

<label for="quantity">I would like to receive <input

↵type="text" name="quantity" id="quantity"> copies of <cite>

↵The HTML5 Herald</cite></label>

</li>

<li>

<label for="upsell">Also sign me up for <cite>The CSS3

↵Chronicle</cite></label>

<input type="checkbox" id="upsell" name="upsell">

</li>

<li>

<input type="submit" id="register-submit" value="Send Post

↵Haste">

</li>

</ul>

For improved accessibility, whenever the required attribute is included, add the ARIA

attribute aria-required="true". Many screen readers

lack support for the new HTML5 attributes, but many

do have support for WAI-ARIA roles, so there’s a chance that adding this role

could let a user know that the field is required—see Appendix B for a brief introduction to

WAI-ARIA.

Figure 4.1, Figure 4.2, and Figure 4.3 show the behavior of the required attribute when you attempt to submit the form.

You can style required form elements with the

:required pseudo-class. You can also style valid or

invalid fields with the

:valid and

:invalid pseudo-classes. With these

pseudo-classes and a little CSS magic, you can provide visual cues to

sighted users indicating which fields are required, and also give

feedback for successful data entry:

input:required {

background-image: url('../images/required.png'),

}

input:focus:invalid {

background-image: url('../images/invalid.png'),

}

input:focus:valid {

background-image: url('../images/valid.png'),

}

We’re adding a background image (an asterisk) to required form fields. We’ve also added separate background images to valid and invalid fields. The change is only apparent when the form element has focus, to keep the form from looking too cluttered.

Warning: Beware Default Styles

Note that Firefox 4 applies its own styles to invalid elements (a red shadow), as shown in Figure 4.1 earlier. You may want to remove the native drop shadow with the following CSS:

:invalid { box-shadow: none; }

Tip: Backwards Compatibility

Older browsers mightn’t support the

:required pseudo-class, but you can still provide

targeted styles using the attribute selector:

input:required,

input[required] {

background-image: url('../images/required.png'),

}

You can also use this attribute as a hook for form validation

in browsers without support for HTML5. Your JavaScript code can check for the presence of the

required attribute on empty

elements, and fail to submit the form if any are found.

The placeholder attribute

allows a short hint to be displayed inside the form element, space

permitting, telling the user what data should be entered in that field.

The placeholder text disappears when the field gains focus, and

reappears on blur if no data was entered. Developers have provided this

functionality with JavaScript for years, but in HTML5 the placeholder

attribute allows it to happen natively, with no JavaScript

required.

For The HTML5 Herald’s sign-up form, we’ll put a placeholder on the website URL and start date fields:

<li> <label for="url">My website is located at:</label> <input type="text" id="url" name="url" ↵placeholder="http://example.com"> </li> … <li> <label for="startdate">Please start my subscription on:</label> <input type="text" id="startdate" name="startdate" required ↵aria-required="true" placeholder="1911-03-17"> </li>

Because support for the placeholder attribute is still restricted to

the latest crop of browsers, you shouldn’t rely on it as the only way to

inform users of requirements. If your hint exceeds the size of the

field, describe the requirements in the input’s title attribute or in text next to the

input element.

Currently, Safari, Chrome, Opera, and Firefox 4 support the

placeholder attribute.

Like everything else in this chapter, it won’t hurt

nonsupporting browsers to include the placeholder attribute.

As with the required

attribute, you can make use of the placeholder attribute and its value to

make older browsers behave as if they supported it—all by using a

little JavaScript magic.

Here’s how you’d go about it: first, use JavaScript to determine

which browsers lack support. Then, in those browsers, use a function

that creates a “faux” placeholder. The function needs to determine

which form fields contain the placeholder attribute, then temporarily

grab that attribute’s content and put it in the value attribute.

Then you need to set up two event handlers: one to clear the

field’s value on focus, and another to replace the placeholder value

on blur if the form control’s value is still null

or an empty string. If you do use this trick, make sure that the value

of your placeholder attribute

isn’t one that users might actually enter, and remember to clear the

faux placeholder when the form is submitted. Otherwise, you’ll have

lots of “(XXX) XXX-XXXX” submissions!

Let’s look at a sample JavaScript snippet (using the jQuery

JavaScript library for brevity) to progressively enhance our form

elements using the placeholder

attribute.

Note: jQuery

In the code examples that follow, and throughout the rest of the book, we’ll be using the jQuery JavaScript library. While all the effects we’ll be adding could be accomplished with plain JavaScript, we find that jQuery code is generally more readable; thus, it helps to illustrate what we want to focus on—the HTML5 APIs—rather than spending time explaining a lot of hairy JavaScript.

Here’s our placeholder polyfill:

<script>

if(!Modernizr.input.placeholder) {

$("input[placeholder], textarea[placeholder]").each(function() {

if($(this).val()==""){

$(this).val($(this).attr("placeholder"));

$(this).focus(function(){

if($(this).val()==$(this).attr("placeholder")) {

$(this).val("");

$(this).removeClass('placeholder'),

}

});

$(this).blur(function(){

if($(this).val()==""){

$(this).val($(this).attr("placeholder"));

$(this).addClass('placeholder'),

}

});

}

});

$('form').submit(function(){

// first do all the checking for required

// element and form validation.

// Only remove placeholders before final submission

var placeheld = $(this).find('[placeholder]'),

for(var i=0; i<placeheld.length; i++){

if($(placeheld[i]).val() ==

↵$(placeheld[i]).attr('placeholder')) {

// if not required, set value to empty before submitting

$(placeheld[i]).attr('value',''),

}

}

});

}

</script>

The first point to note about this script is that we’re using

the

Modernizr

JavaScript library to detect support for the placeholder attribute. There’s more

information about Modernizr in Appendix A,

but for now it’s enough to understand that it provides you with a

whole raft of true or false

properties for the presence of given HTML5 and CSS3 features in the

browser. In this case, the property we’re using is fairly

self-explanatory. Modernizr.input.placeholder

will be true if the browser supports placeholder, and false

if it doesn’t.

If we’ve determined that placeholder support is absent, we grab

all the input and textarea elements on the page with a

placeholder attribute. For each

of them, we check that the value isn’t empty, then replace that value

with the value of the placeholder

attribute. In the process, we add the placeholder

class to the element, so you can lighten

the color of the font in your CSS, or otherwise make it look more like

a native placeholder. When the user focuses on the input with the faux

placeholder, the script clears the value and removes the class. When the user removes focus, the

script checks to see if there is a value. If not, we add the

placeholder text and class back

in.

This is a great example of an HTML5 polyfill: we use JavaScript to provide support only for those browsers that lack native support, and we do it by leveraging the HTML5 elements and attributes already in place, rather than resorting to additional classes or hardcoded values in our JavaScript.

The pattern attribute enables

you to provide a regular expression that the user’s input must match in

order to be considered valid. For any input where the user can enter free-form

text, you can limit what syntax is acceptable with the pattern attribute.

The regular expression language used in patterns is the same

Perl-based regular expression syntax as JavaScript, except that the

pattern attribute must match the

entire value, not just a subset. When including a pattern, you should always indicate to users

what is the expected (and required) pattern. Since browsers currently

show the value of the title

attribute on hover like a tooltip, include pattern instructions that are

more detailed than placeholder text, and which form a coherent

statement.

Note: The Skinny on Regular Expressions

Regular expressions are a feature of most

programming languages that allow developers to specify patterns of

characters and check to see if a given string matches the pattern.

Regular expressions are famously indecipherable to the uninitiated.

For instance, one possible regular expression to check if a string is

formatted as an email address looks like this:

[A-Z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Z0-9.-]+.[A-Z]{2,4}.

A full tutorial on the syntax of regular expressions is beyond the scope of this book, but there are plenty of great resources and tutorials available online if you’d like to learn. Alternately, you can search the Web or ask around on forums for a pattern that will serve your purposes.

For a simple example, let’s add a pattern attribute to the password field in

our form. We want to enforce the requirement that the password be at

least six characters long, with no spaces:

<li>

<label for="password">I would like my password to be:</label>

<p>(at least 6 characters, no spaces)</p>

<input type="password" id="password" name="password" required

↵pattern="S{6,}">

</li>

S refers to “any nonwhitespace character,” and

{6,} means “at least six times.” If you wanted to

stipulate the maximum amount of characters, the syntax would be, for

example, S{6,10} for between six and ten

characters.

As with the required

attribute, the pattern attribute

will prevent the form being submitted if the pattern isn’t matched, and

will provide an error message.

If your pattern is not a valid regular expression, it will be

ignored for the purposes of validation. Note also that similar to the

placeholder and required attributes, you can use the value

of this attribute to provide the basis for your JavaScript validation

code for nonsupporting browsers.

The Boolean disabled

attribute has been around longer than HTML5, but it has been expanded

on, to a degree. It can be used with any form control except the new

output element—and unlike previous

versions of HTML, HTML5 allows you to set the disabled attribute on a fieldset and have it apply to all the form

elements contained in that fieldset.

Generally, form elements with the disabled attribute have the content grayed

out in the browser—the text is lighter than the color of values in

enabled form controls. Browsers will prohibit the user from focusing on

a form control that has the disabled attribute set. This attribute is

often used to disable the submit button until all fields are correctly

filled out, for example.

You can employ the

:disabled pseudo-class in your CSS to

style disabled form controls.

Form controls with the disabled attribute aren’t submitted along

with the form; so their values will be inaccessible to your form

processing code on the server side. If you want a value that users are

unable to edit, but can still see and submit, use the readonly attribute.

The readonly attribute is

similar to the disabled attribute:

it makes it impossible for the user to edit the form field. Unlike

disabled, however, the field

can receive focus, and its value is submitted with

the form.

In a comments form, we may want to include the URL of the current page or the title of the article that is being commented on, letting the user know that we are collecting this data without allowing them to change it:

<label for="about">Article Title</label> <input type="text" name="about" id="about" readonly>

The multiple attribute, if

present, indicates that multiple values can be entered in a form

control. While it has been available in previous versions of HTML, it

only applied to the select element.

In HTML5, it can be added to email and

file input types as well. If present, the user can

select more than one file, or include several comma-separated email

addresses.

At the time of writing, multiple file input is only supported in Chrome, Opera, and Firefox.

Note: Spaces or Commas?

You may notice that the iOS touch keyboard for email inputs includes a space. Of course, spaces aren’t permitted in email addresses, but some browsers allow you to separate multiple emails with spaces. Firefox 4 and Opera both support multiple emails separated with either commas or spaces. WebKit has no support for the space separator, even though the space is included in the touch keyboard.

Soon, all browsers will allow extra whitespace. This is how most users will likely enter the data; plus, this allowance has recently been added to the specification.

Not to be confused with the form element, the form

attribute in HTML5

allows you to associate form elements with forms in which they’re not

nested. This means you can now associate a fieldset or form control with

any other form in the document. The form attribute takes as its value the

id of the form element with which the fieldset or

control should be associated.

If the attribute is omitted, the control will only be submitted

with the form in which it’s

nested.

The autocomplete attribute

specifies whether the form, or a form control, should have autocomplete

functionality. For most form fields, this will be a drop-down that

appears when the user begins typing. For password fields, it’s the

ability to save the password in the browser. Support for this attribute

has been present in browsers for years, though it was never in the

specification until HTML5.

By default, autocomplete is on. You may have noticed this the last

time you filled out a form. In order to disable it, use

autocomplete="off". This is a good idea for sensitive

information, such as a credit card number, or information that will

never need to be reused, like a CAPTCHA.

Autocompletion is also controlled by the browser. The user will

have to turn on the autocomplete functionality in their browser for it

to work at all; however, setting the autocomplete attribute to off overrides this preference.

Datalists are currently only supported in Firefox and

Opera, but they are very cool. They fulfill a common requirement: a text

field with a set of predefined autocomplete options. Unlike the select element, the user can enter whatever

data they like, but they’ll be presented with a set of suggested options

in a drop-down as they type.

The datalist element, much like

select, is a list of options, with

each one placed in an option element.

You then associate the datalist with

an input using the list attribute

on the input. The list attribute takes as its value the

id attribute of the datalist you want to associate with the input.

One datalist can be associated with

several input fields.

Here’s what this would look like in practice:

<label for="favcolor">Favorite Color</label> <input type="text" list="colors" id="favcolor" name="favcolor"> <datalist id="colors"> <option value="Blue"> <option value="Green"> <option value="Pink"> <option value="Purple"> </datalist>

In supporting browsers, this will display a simple text field that drops down a list of suggested answers when focused. Figure 4.4 shows what this looks like.

You’re probably already familiar with the input element’s type attribute. This is the attribute that

determines what kind of form input will be presented to the user. If it is

omitted—or, in the case of new input types and older browsers, not

understood—it still works: the input

will default to type="text". This is the key that makes

HTML5 forms usable today. If you use a new input type, like

email or search, older browsers will

simply present users with a standard text field.

Our sign-up form currently uses four of the ten input types you’re

familiar with: checkbox, text,

password, and submit. Here’s the

full list of types that were available before HTML5:

-

button -

checkbox -

file -

hidden -

image -

password -

radio -

reset -

submit -

text

HTML5 gives us input types that provide for more data-specific UI elements and native data validation. HTML5 has a total of 13 new input types:

-

search -

email -

url -

tel -

datetime -

date -

month -

week -

time -

datetime-local -

number -

range -

color

Let’s look at each of these new types in detail, and see how we can put them to use.

The search input type

(type="search") provides a search field—a one-line

text input control for entering one or more search terms. The spec

states:

The difference between the text state and the search state is primarily stylistic: on platforms where search fields are distinguished from regular text fields, the search state might result in an appearance consistent with the platform's search fields rather than appearing like a regular text field.

Many browsers style search inputs in a manner

consistent with the browser or the operating system’s search boxes. Some

browsers have added the ability to clear the input with the click of a mouse, by providing an

icon once text is entered into the field. You

can see this behavior in Chrome on Mac OS X in Figure 4.5.

Currently, only Chrome and Safari provide a button to clear the field. Opera 11 displays a rounded corner box without a control to clear the field, but switches to display a normal text field if any styling, such as a background color, is applied.

While you can still use type="text" for search

fields, the new search type is a visual cue as to where the user needs

to go to search the site, and provides an interface the user is

accustomed to. The HTML5 Herald has no search

field, but here’s an example of how you’d use it:

<form id="search" method="get">

<input type="search" id="s" name="s">

<input type="submit" value="Search">

</form>

Since search, like all the new input types,

appears as a regular text box in nonsupporting browsers, there’s no

reason not to use it when appropriate.

The email type

(type="email") is, unsurprisingly, used for

specifying one or more email addresses. It supports the Boolean multiple attribute, allowing for multiple,

comma-separated email addresses.

Let’s change our form to use type="email" for

the registrant’s email address:

<label for="email">My email address is</label>

<input type="email" id="email" name="email">

If you change the input type from text to

email, as we’ve done here, you’ll notice no visible

change in the user interface; the input still looks like a plain text

field. However, there are differences behind the scenes.

The change becomes apparent if you’re using an iOS device. When you focus on the email field, the iPhone, iPad, and iPod will all display a keyboard optimized for email entry (with a shortcut key for the @ symbol), as shown in Figure 4.6.

Firefox, Chrome, and Opera also provide error messaging for

email inputs: if you try to submit a form with

content unrecognizable as one or more email addresses, the browser will

tell you what is wrong. The default error messages are shown in Figure 4.7.

Figure 4.7. Error messages for incorrectly formatted email addresses on Firefox 4 (left) and Opera 11 (right)

Note: Custom Validation Messages

Don’t like the error messages provided? In some

browsers, you can set your own with

.setCustomValidity(errorMsg).

setCustomValidity takes as its only parameter

the error message you want to provide. You can pass an empty string to

setCustomValidity if you want to remove the

error message entirely.

Unfortunately, while you can change the content of the message, you’re stuck with its appearance, at least for now.

The url input (type="url")

is used for specifying a web address. Much like

email, it will display as a normal text field. On

many touch screens, the on-screen keyboard displayed will be optimized

for web address entry, with a forward slash (/) and a “.com” shortcut

key.

Let’s update our registration form to use the

url input type:

<label for="url">My website is located at:</label>

<input type="url" id="url" name="url">

Opera, Firefox, and WebKit support the

url input type, reporting the input as invalid if the

URL is incorrectly formatted. Only the general format of a URL is

validated, so, for example, q://example.xyz will be

considered valid, even though q:// isn’t a real

protocol and .xyz isn’t a real top-level domain. As

such, if you want the value entered to conform to a more specific

format, provide information in your label (or in a placeholder) to let

your users know, and use the pattern attribute to ensure that it’s

correct—we’ll cover pattern in

detail later in this chapter.

Note: WebKit

When we refer to WebKit in this book, we’re referring to browsers that use the WebKit rendering engine. This includes Safari (both on the desktop and on iOS), Google Chrome, the Android browser, and a number of other mobile browsers. You can find more information about the WebKit open source project at http://www.webkit.org/.

For telephone numbers, use the tel input type

(type="tel"). Unlike the url and

email types, the tel type doesn’t

enforce a particular syntax or pattern. Letters and numbers—indeed, any

characters other than new lines or carriage returns—are valid. There’s a good reason for this: all over the world

countries have different types of valid phone numbers, with various

lengths and punctuation, so it would be impossible to specify a single

format as standard. For example, in the USA, +1(415)555-1212 is just as

well understood as 415.555.1212.

You can encourage a particular format by including a placeholder

with the correct syntax, or a comment after the input with an example.

Additionally, you can stipulate a format by using the pattern attribute or the

setCustomValidity method to

provide for client-side validation.

The number type

(type="number") provides an input for entering a

number. Usually, this is a “spinner” box, where you can either enter a

number or click on the up or down arrows to select a number.

Let’s change our quantity field to use the

number input type:

<label for="quantity">I would like to receive <input type="number"

↵name="quantity" id="quantity"> copies of <cite>The HTML5 Herald

↵</cite></label>

Figure 4.8 shows what this looks like in Opera.

The number input has

min and

max attributes to

specify the minimum and maximum values allowed. We highly recommend that

you use these, otherwise the up and down arrows might lead to different

(and very odd) values depending on the browser.

Warning: When is a number not a number?

There will be times when you may think you want to use

number, when in reality another input type is more

appropriate. For example, it might seem to make sense that a street

address should be a number. But think about it: would you want to

click the spinner box all the way up to 34154? More importantly, many

street numbers have non-numeric portions: think 24½ or 36B, neither of

which work with the number input type.

Additionally, account numbers may be a mixture of letters and

numbers, or have dashes. If you know the pattern of your number, use

the pattern attribute. Just

remember not to use number if the range is

extensive or the number could contain non-numeric characters and the

field is required. If the field is optional, you might want to use

number anyway, in order to prompt the number

keyboard as the default on touchscreen devices.

If you do decide that number is the way to

go, remember also that the

pattern attribute

is unsupported in the number type. In other words,

if the browser supports the number type, that

supersedes any pattern. That

said, feel free to include a pattern, in case the browser supports

pattern but not the

number input type.

You can also provide a

step attribute, which

determines the increment by which the number steps up or down when

clicking the up and down arrows. The min, max, and step attributes are supported in Opera and

WebKit.

On many touchscreen devices, focusing on a

number input type will bring up a number touch pad

(rather than a full keyboard).

The range input type

(type="range") displays a slider control in browsers that support it (currently

Opera and WebKit). As with the number type, it allows the

min,

max, and

step attributes. The

difference between number and

range, according to the spec, is that the exact value

of the number is unimportant with range. It’s ideal

for inputs where you want an imprecise number; for example, a customer

satisfaction survey asking clients to rate aspects of the service they

received.

Let’s change our registration form to use the

range input type. The field asking users to rate

their knowledge of HTML5 on a scale of 1 to 10 is perfect:

<label for="rating">On a scale of 1 to 10, my knowledge of HTML5

↵is:</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="10" name="rating" type="range">

The step attribute defaults

to 1, so it’s not required. Figure 4.9 shows what

this input type looks like in Safari.

The default value of a range is the midpoint of the slider—in other words, halfway between the minimum and the maximum.

The spec allows for a reversed slider (with values from right to left instead of from left to right) if the maximum specified is less than the minimum; however, currently no browsers support this.

The color input type

(type="color") provides the user with a color picker—or at least it does in Opera (and,

surprisingly, in the built-in browser on newer BlackBerry smartphones).

The color picker should return a hexadecimal RGB color value, such as

#FF3300.

Until this input type is fully supported, if you want to use a

color input, provide placeholder text indicating that a hexadecimal RGB

color format is required, and use the pattern attribute to restrict the entry to

only valid hexadecimal color values.

We don’t use color in our form, but, if we did, it would look a little like this:

<label for="clr">Color: </label>

<input id="clr" name="clr" type="text" placeholder="#FFFFFF"

↵pattern="#(?:[0-9A-Fa-f]{6}|[0-9A-Fa-f]{3})" required>

The resulting color picker is shown in Figure 4.10. Clicking the button brings up a full color wheel, allowing the user to select any hexadecimal color value.

WebKit browsers support the color input type as well, and can indicate whether the color is valid, but don’t provide a color picker … yet.

There are several new date and time input types, including

date, datetime,

datetime-local, month,

time, and week. All date and time

inputs accept data formatted according to the ISO 8601

standard.

-

date -

This comprises the date (year, month, and day), but no time; for example, 2004-06-24.

-

month -

Only includes the year and month; for example, 2012-12.

-

week -

This covers the year and week number (from 1 to 52); for example, 2011-W01 or 2012-W52.

-

time -

A time of day, using the military format (24-hour clock); for example, 22:00 instead of 10.00 p.m.

-

datetime -

This includes both the date and time, separated by a “T”, and followed by either a “Z” to represent UTC (Coordinated Universal Time), or by a time zone specified with a + or - character. For example, “2011-03-17T10:45-5:00” represents 10:45am on the 17th of March, 2011, in the UTC minus 5 hours time zone (Eastern Standard Time).

-

datetime-local -

Identical to

datetime, except that it omits the time zone.

The most commonly used of these types is date.

The specifications call for the browser to display a date control, yet

at the time of writing, only Opera does this by providing a calendar control.

Let’s change our subscription start date field to use the

date input type:

<label for="startdate">Please start my subscription on:</label>

<input type="date" min="1904-03-17" max="1904-05-17"

↵id="startdate" name="startdate" required aria-required="true"

↵placeholder="1911-03-17">

Now, we’ll have a calendar control when we view our form in Opera, as shown in Figure 4.11. Unfortunately, it’s unable to be styled with CSS at present.

For the month and week

types, Opera displays the same date picker, but only allows the user to

select full months or weeks. In those cases, individual days are unable

to be selected; instead, clicking on a day selects the whole month or

week.

Currently, WebKit provides some support for

the date input type, providing a user interface

similar to the number type, with up and down arrows.

Safari behaves a little oddly when it comes to this control; the default

value is the very first day of the Gregorian calendar: 1582-10-15. The

default in Chrome is 0001-01-01, and the maximum is 275760-09-13. Opera

functions more predictably, with the default value being the current

date. Because of these oddities, we highly recommend including a minimum

and maximum when using any of the date-based input types (all those

listed above, except time). As with

number, this is done with the min and max attributes.

The placeholder

attribute we added to our start date field earlier is made redundant in

Opera by the date picker interface, but it makes sense to leave it in

place to guide users of other browsers.

Eventually, when all browsers support the UI of all the new input

types, the placeholder attribute

will only be relevant on text,

search, URL,

telephone, email, and

password types. Until then, placeholders are a good

way to hint to your users what kind of data is expected in those

fields—remember that they’ll just look like regular text fields in

nonsupporting browsers.

Tip: Dynamic Dates

In our example above, we hardcoded the min and max values into our HTML. If, for example,

you wanted the minimum to be the day after the current date (this

makes sense for a newspaper subscription start date), this would

require updating the HTML every day. The best thing to do is

dynamically generate the minimum and maximum allowed dates on the

server side. A little PHP can go a long way:

<?php

function daysFromNow($days){

$added = ($days * 24 * 3600) + time();

echo(date("Y-m-d", $added));

}

?>

In our markup where we had static dates, we now dynamically create them with the above function:

<li>

<label for="startdate">Please start my subscription on:

↵</label>

<input type="date" min="<?php daysFromNow(1); ?>"

↵max="<?php daysFromNow(60); ?>" id="startdate"

↵name="startdate" required aria-required="true"

↵placeholder="1911-03-17">

</li>

This way, the user is limited to entering dates that make sense in the context of the form.

You can also include the

step attribute with

the date and time input types. For

example, step="6" on month will

limit the user to selecting either January or July. On

time and datetime inputs, the

step attribute must be expressed in

seconds, so step="900" on the time input type will

cause the input to step in increments of 15 minutes.

We’ve covered the new values for the input element’s type attribute, along with some attributes

that are valid on most form elements. But HTML5 web forms still have more

to offer us! There are four new form elements in HTML5: output, keygen, progress, and meter. We covered progress and meter in the last chapter, since they’re often

useful outside of forms, so let’s take a look at the other two

elements.

The purpose of the output

element is to accept and display the result of a calculation. The output

element should be used when the user can see the value, but not directly

manipulate it, and when the value can be derived from other values

entered in the form. An example use might be the total cost calculated

after shipping and taxes in a shopping cart.

The output element’s value is

contained between the opening and closing tags. Generally, it will make

sense to use JavaScript in the browser to update this value. The

output element has a

for attribute, which

is used to reference the ids of

form fields whose values went into the calculation of the output element’s value.

It’s worth noting that the output element’s name and value are submitted

along with the form.

The keygen element is a control

for generating a public-private

keypair and for submitting the public key from that key pair.

Opera, WebKit, and Firefox all support this element, rendering it as a

drop-down menu with options for the length of the generated keys; all

provide different options, though.

The keygen element introduces

two new attributes: the challenge

attribute specifies a string that is submitted along with the public

key, and the keytype attribute

specifies the type of key generated. At the time of writing, the only

supported keytype value is rsa, a common algorithm used in public-key

cryptography.

There have been a few other changes to form controls in HTML5.

Throughout this chapter, we’ve been talking about attributes that

apply to various form field elements; however, there are also some new

attributes specific to the form

element itself.

First, as we’ve seen, HTML5 provides a number of ways to natively

validate form fields; certain input types such as

email and url, for example, as

well as the required and pattern attributes. You may, however, want

to use these input types and attributes for styling or semantic reasons

without preventing the form being submitted. The new Boolean

novalidate attribute

allows a form to be submitted without native validation of its

fields.

Next, forms no longer need to have the

action attribute

defined. If omitted, the form will behave as though the action were set to the current page.

Lastly, the

autocomplete

attribute we introduced earlier can also be added directly to the

form element; in this case, it will

apply to all fields in that form unless those fields override it with

their own autocomplete

attribute.

In HTML5, you can have an optgroup as a child of another optgroup, which is useful for multilevel

select menus.

In HTML 4, we were required to specify a textarea element’s size by specifying values

for the rows and cols attributes. In HTML5, these attributes

are no longer required; you should use CSS to define a textarea’s width and height.

New in HTML5 is the

wrap attribute. This

attribute applies to the textarea

element, and can have the values soft (the default) or hard. With soft, the text is submitted without

line breaks other than those actually entered by the user,

whereas hard will submit any line

breaks introduced by the browser due to the size of the field. If you

set the wrap to hard, you need to specify a cols attribute.

As support for HTML5 input elements and attributes grows, sites will require less and less JavaScript for client-side validation and user interface enhancements, while browsers handle most of the heavy lifting. Legacy user agents are likely to stick around for the foreseeable future, but there is no reason to avoid moving forward and using HTML5 web forms, with appropriate polyfills and fallbacks filling the gaps where required.

In the next chapter, we’ll continue fleshing out The HTML5 Herald by adding what many consider to be HTML5’s killer feature: native video and audio.