Chapter Eight

Working Practices

The working practices presented in this chapter are commonly accepted guidelines, or good tips, for you to think about while you are editing. Some offer specific techniques to follow, while others simply suggest some good habits that you may consider as you work. You may not encounter these precise scenarios on every job or in each motion media project, but you should be aware that they may come up. You will learn how to recognize them and you will find ways to address them appropriately. The working practices have been developed over time and have been found to work within many editing styles and within different genres. Each project should be viewed with fresh eyes and you will be left to judge whether or not these working practices apply to the piece that you are editing.

It should be noted that in today’s highly visual media marketplace there are many venues where motion images are displayed. The variety of television programming, webisodes, commercials, short films, feature films, documentaries, promotional videos, broadcast news packages, etc. all require some degree of editing before they are experienced by the viewing public. As you advance in your editing career, you will learn what each of these program types requires for its individual editorial workflow and established styles, etc. Starting with the following section of working practices as a solid base, you will be in a good position to fine-tune and augment your own list of editing “dos” and “don’ts.”

Finally, there will be cases where an editor has done everything right – the correct type of edit, the correct elements, etc. – so that in theory the cut or dissolve or wipe should work. But it does not. One of the skills of an editor is to analyze the material and find out why the awkward edit exists. Of course, it could be that an exact cause cannot be found, but it is still up to you to find a solution. Editing is not a perfect craft. There is always room for creativity and discovery, and that is part of the fun of the process.

1. Pay Careful Attention to Media and Project Organization

Reason

As much as editing is about creative, visual storytelling, the process relies heavily on efficiency and timeliness. Establishing good habits of project asset management and organization will help an editor to work more confidently through any project.

Solution

Known drive allocations, clear folder structures, and purposeful naming conventions across the board can go a long way in helping any person involved with the post-production workflow to stay on top of his or her project’s materials. Solid organization is key – especially if more than one person has to share time working on the video piece.

Whenever possible, original source media files need to have a complete set of copies on another drive as back-up. Keep your functional set of source files in the same folder on the same drive throughout the edit. Give your project a name that will be short and clear to all who need to access it. It can be helpful to pre-create bins/folders inside your project for some of the most common assets: footage, sequence versions, music, SFX, titles, imported graphics, etc. Using a date as part of a name (for a bin or sequence) can help you to figure out what is old and what is most recent. Many editing software apps have the ability to color code files, sort and sift bin contents, or make duplicates of pointer or source files with different names.

Exception

No exceptions. Even the most simple or quick project should follow your same good habits of organization. Keep everything where it belongs and you will reduce your risks of headaches and lower your stress levels.

2. Learn and Use Keyboard Shortcuts

Reason

All video-editing applications have some keyboard shortcuts available and the professional-level software has many that can even be customized per user. Moving the mouse and clicking buttons and menus in the interface is a good way to first figure out how an application functions, but it is time consuming and not entirely elegant. Learning and using the available keyboard shortcuts that execute commands in the application will save time. Speed and efficiency are highly valued in post-production.

Solution

When you are first starting out, take note of the equivalent keyboard command each time you mouse-open a menu to select a function. Try new keyboard shortcuts every time you work in that particular software. Over time, you will remember what lives where and you will use the shortcuts more and more. Most applications will have a master list of keyboard commands in their Help menu. Some even come with a “cheat-sheet” PDF or printout that shows the icon for the command on each programmed key cap.

As several of the major video-editing applications can live on either a Windows or a Macintosh operating system, it would also be very wise for you to become familiar with some basic operating system keyboard shortcuts as well.

Exception

Certain functions in each video-editing application cannot be mapped to keyboard keystrokes, so they can only be selected by using the mouse cursor to click within the interface. Also, depending on your software, the layout of the interface buttons for simple and frequently used commands may make it easier sometimes to just click the mouse. The “Function” keys on certain small keyboard laptops can be a bit snarky at times as well and may have to be “freed” from operating system command mapping. Also be aware that some apps embed certain commands on the numeric keypad of full-size keyboards and, sometimes, such key equivalents are not present on laptop keyboards.

FIGURE 8.1 Using keyboard shortcuts within the editing application will greatly increase an editor’s efficiency. Memorizing and using the most common operating system keyboard commands is also advisable.

3. Organize Your Timeline Tracks and Maintain Consistency Across Projects

Reason

You can potentially have many different types of video and audio sources that will need to find a home in your sequence. If you organize your video and audio tracks in the timeline so that they contain particular assets, you always know where to place things. Simplicity and clarity lead to efficiency and speed during the editing process.

Solution

Create an order to the track content. Perhaps V1 and V2 are reserved for production video, V3 is for keyed titles, and V4 is for keyed imported graphics. On the audio side, you may place sync audio production tracks on A1 and A2, voice-over narration on A3 and A4, ambient clips (NATS) on A5 and A6, music tracks on A7 through A10, SFX on A11 and A12, etc.

The order of video tracks does matter for image processing with special effects and keyed titles, etc. but audio tracks can live wherever you wish. The point is that you should figure out an orderly arrangement for media types that fit your workflow and your style. If you maintain this track organization across sequences and across editing jobs, then you will work more efficiently. Capability and speed are valuable skills for an editor to possess.

Exception

Even the most basic of video sequences will still default to production footage living on V1 and sync audio living on A1 and A2. That is an aspect of track media organization. Also be aware that certain post-production facilities use prescribed track orders of their own to maintain consistency across their edit suites and edited programming. It is always best to check with the producers or engineers to see how they want things set up when you are doing work in someone else’s “house.”

FIGURE 8.2 Some software allows for track panel renaming. This may help with sequence organization across projects.

4. Keep Your Rough Cut Long

Reason

No matter what kind of programming you are editing, this guideline applies. Keep your sequence longer in the first pass or two after the full construction of the assembly edit. Without knowing overall pacing or timing issues or scene-ordering issues, it will be hard to make final decisions about shot, scene, and sequence length. You will be better able to judge what can be removed after the entire assembly edit has been viewed a few times. If usable material is already missing from the rough cut, then you may be inadvertently ignoring a better creative opportunity.

Solution

From the outset, you should include everything from picture and sound tracks that you feel will help to properly show/tell the story. At that early stage of editing, you really do not know what will be useful or superfluous, so keep it all in. After a pass or two at the entire piece, you will get a much better feel for what works and what does not, what should stay and what should really go.

Often, you have much more material than the final running time of the program will allow (30-second commercial, 15-minute educational video, 30-minute situation comedy show, two-hour feature film, etc.). Some things that were initially included in your first versions of the edit will stand out as unnecessary. Other times, you will have to make hard choices that call for removing very good segments just to make the final running time cut-off. Regardless, you should always start with the most material and then pare it down – that is what editing is all about.

Exception

Some news packages have extremely short airtime and you will not be able to pad out the first cuts and then tweak. You will most likely have very little time to finesse and you will simply have just enough time to cut something together to get it to air in the right time slot.

Motion media pieces made for the web (YouTube, Hulu, vlogs, even Netflix and Amazon Prime originals) are not specifically limited to time slot durations (unlike shows that air on traditional commercial broadcast television). These projects can add more material if the quality of the show can bear it out – although many do keep to the traditional time slot durations because they are future-proofing their sale and playback by traditional television broadcasting networks.

5. Review Each Edit or Series of Edits as You Make Them

Reason

You will not know how the shot transition works if you do not watch it play back after you perform the edit. Without reviewing the edits in your sequence, with real-time playback and not scrubbing, you will not be able to appropriately judge any matching action, dialogue continuity, shot timing, overall scene pacing, etc.

Solution

After an edit or a series of edits in the assembly stage, you should move your playhead earlier in the timeline and watch across the shots and the cuts that you have just laid in. Watching every single edit may take up some time during this phase, but you need to gauge your progress frequently. During the rough and fine cut stages, you should review each trim and tweak as it is being worked on to know if you are getting the timing that is needed. After you complete an entire scene, it would be wise to sit back, watch it through from beginning to end, and note any moments that seem to require more attention.

Exception

Even projects that have a very fast turnaround time will require the editing and reviewing process.

6. Duplicate Your Sequence Before Making Major Changes

Reason

Moving ahead with your sequence construction is your main goal, but sometimes you can take one step forward just to take two steps back. Rather than keeping one version of your sequence that you constantly change around trying to get to your final edit, it is preferable to copy, duplicate, or iterate your sequence so you maintain an archive of your progress across time.

Solution

Each video-editing software application should have a way for an editor to make a copy of the sequence under construction in the project. Some apps copy while others duplicate, but your goal is to keep your current version as it is and make any new changes (especially significant changes) to a new version. Some editors append things like “_v1” or “_v16” to the name of the sequence to keep track of the chronology of versions. Others tag the date to the end of the name, etc. This way, if you (or the client) are displeased with the direction in which a particular section of the sequence is going, it is easy to open an older, archived version and replace parts in the newer version as needed.

Exception

If your sequence has a very brief turnaround time or it is just a fun project for yourself, this may not be necessary, but otherwise, duplicating/copying a sequence into versions can become a good habit to get into.

7. Seek Feedback While Editing Your Motion Picture

Reason

A project worked on for many hours, days, or sometimes months can become stale to you over time. The fresh eyes of other individuals may help you to see weaknesses that you could no longer objectively notice. Parts that you have grown fond of may not actually be suitable to the overall story. It may also be that you are having some difficulties with a certain scene’s assembly or you are hitting a wall trying to find ways to bridge two disparate segments of the project.

Solution

It is strongly advisable for an editor to show his or her work to other people to get their feedback. Just because you, as an editor, think something really works does not mean that it will play the same way for others. Often, showing your work to other people will bring up points that need to be addressed, edits that do not quite work, or even places that are rather successful.

Listening to constructive feedback and suggestions from other people and creating your own solution to those potential problem areas is an essential skill that you will need to develop as an editor. You may feel that you have done everything right, but the opinions of others bear a certain weight as well – especially if they are paying you.

Exception

Unless you live alone in a cave somewhere, you should always make time to have other people review your edited piece. No one should work in a feedback vacuum.

8. Put Aside Your Edited Sequence for a While and Watch It Again with Fresh Eyes

Reason

When you are the editor of a feature film or any long-form documentary piece, etc., you become “married” to the movie. You live with it day in and day out, sometimes for weeks or months at a time. You are often listening to the same sections over and over and over again. You grow to anticipate the words and the pictures until they no longer really stand out in your mind but are part of the editing “wallpaper.” It becomes very easy to blind yourself to edits that are not working or entire sections that may play better in another location within the sequence.

Solution

Time allowing, you would be wise to take a break from the editing process. A day or two away from the well-known material will help you to forget the exact pacing, the cut points, the lines of dialogue, etc. – perhaps not forget entirely, but you will be watching the piece with less anticipation. This respite should give you fresh eyes and ears to view and listen to your story. When you approach the same material with fresh senses, you may pick up on which edits are not working and which scenes within the piece may play better elsewhere.

Exception

Obviously, if you are involved with much shorter or more straightforward cutting jobs that have a quick turnaround time, then you will not have the luxury of taking a day or two away from the material to refresh your senses. You will hope that an overnight break will be enough time away for you to be more critical of your own work come morning.

9. Use Shots with Matching Headroom When Cutting a Dialogue Scene

Reason

Let us assume that the clean single MCU shots found in Figure 8.3 are part of an established two-person dialogue scene. To cut from a shot with correctly framed headroom to another shot with incorrectly framed headroom will look as if one of the subjects has suddenly altered her height.

To cut from one take of Character A with incorrectly framed headroom to a good shot of Character B and then back to another correct take of Character A will make it look as if A is bobbing up and down.

Solution

The incorrectly framed headroom shot is nearly impossible to correct. Video-editing software may have the ability to resize and reframe the footage, but enlarging video frames may cause image quality to degrade depending on the resolution of the original footage. If the poorly framed MCU of Character A is of high enough resolution (full HD or higher), you could enlarge it to a standard close-up and edit it with the well-framed MCU of Character B. Otherwise, some of the footage might be usable for cutaways, if it is not too badly framed. If there is not more than one take of this action or dialogue delivery, the entire shot might have to be rejected and replaced by another, even if the speaker is not seen to be speaking. An over-the-shoulder two-shot may be a solution – or stick to the wider two-shot as a safety.

Exception

The exception here is when the two shots being edited together both suffer from the same bad headroom framing. Obviously, if the headroom is completely wrong, the shots may not look traditionally well framed, but because you may not be able to do much about it, throw caution to the wind and go for the shots with the best performance regardless of headroom. If the performance is engaging enough, most viewers may not even notice the differences in framing.

FIGURE 8.3 Beware of headroom issues when cutting “answering” coverage shots of a dialogue scene.

10. Avoid Shots Where Distracting Objects Are Too Near to the Subject’s Head

Reason

This is a question of shot composition that has failed at the shooting stage. As an editor, you will not be able to change this questionably composed image. The presence of unwanted lines, shapes, objects, signs, etc. in the shot’s background can be rather confusing or distracting to the viewer. It may also result in a humorous reaction not wanted by the filmmakers at that time. If offered such a shot, it is best not to use it if at all possible (Figure 8.4).

Solution

There really is no solution to this problem short of using some special effects like a picture-in-picture, a split screen, or some kind of mask, clone, or blur effect that either crops or obscures the offending background object. Of course, if the filmmakers made such a composition intentionally for comedic reasons, then it would be appropriate for use.

FIGURE 8.4 Poor shot composition is not the fault of the editor, but the choice to use any of these shots in the final edit does fall under her or his domain. Omit, use effects, or just go for it, but be aware of the possible consequences when the audience observe these oddly placed background objects.

Exception

You may be able to use this shot if it has a very shallow depth of field and the background (containing the offending object) is almost completely out of focus. The only other possible use is in a fast montage, where the shot is seen only for a very brief period of time.

11. Avoid Shots Where the Subject Gets Awkwardly Cut Off at the Edge of the Frame

Reason

This type of framing may be considered aesthetically unpleasing by many viewers, but that would not be your fault for you did not shoot the footage. Attempting to use closer shots (medium shots, medium close-ups) that have such framing will cause complications for the edit. When the partial face of a character is in one shot and then that same face needs to be cut to for the next shot, it will cause a jump cut or potentially a continuity problem with action, line delivery, performance, or screen direction (Figure 8.5).

FIGURE 8.5 Compositions like these can make a smooth edit tricky. Try to avoid using footage that contains missing heads or where portions of faces are only partially visible.

Solution

Sometimes the shot can be used, but it depends what comes before and what comes after. It also depends on the duration of the shot and the type of motion media project being edited.

Exception

These shots could be used in music videos, commercials, experimental films, and maybe in quick-cut action scenes, or where clips before and after do not cause a jump cut.

12. Cut Matched Shots in a Back-and-Forth Dialogue Scene

Reason

As you edit coverage from a traditional dialogue scene between two characters, you will most likely move in from a wide two-shot to tighter singles or over-the-shoulder shots. This allows the audience to get more familiar with the characters and their actions/reactions during the scene.

Established film grammar would suggest that the production team shot matching coverage of each character for this scene (this is not always the case, but let us assume that we have these assets within the footage that you are editing). It is possible that you may have been given a variety of shot types for each character (medium shot, medium close-up, close-up, over-the-shoulder shot, etc.). Matching shots, when recorded with similar focal lengths, at similar distances from the subject, and under similar lighting conditions, often yield similar frame composition, focus depths, etc. Audiences like to see two similar shots cut together as opposed to two mismatched shots within the same scene’s back-and-forth dialogue. It creates a coherence and a flow to the visual imagery.

In Diagram A in Figure 8.6, two people are standing having a conversation. Cameras 1 and 2 are at a similar distance from each subject, Character A and Character B. Both of the shots are taken, for example, at a narrow lens angle (telephoto or long focal length) and both of the shots are framed as medium close-ups. When this is the case, the editor has subjects roughly the same size in the frame and backgrounds that are out of focus to the same extent. The audience get to focus their attention solely on the speaking characters.

FIGURE 8.6 Diagram A – matching coverage generated by reciprocating camera placement and lens angle of view; Diagram B – mismatching coverage due to altered camera distance and focal length; Diagram C – the depth of field changes with focal length. (Photo credits: Anthony Martel)

In Diagram B, the position for Camera 2 has changed. The shot type should remain the same: a medium close-up. So at the new set-up for Camera 2, the lens angle will now have to be wider (shorter focal length). In this case, the background may be in focus and the perspective on the distant background may be altered. Consequently, the editor would be cutting from a medium close-up with an out-of-focus background to a medium close-up with an in-focus background revealing a wider field of view.

Solution

If a selection of good shots is available, then preference should be given to those with similarity in the quality of framing, focus, lighting, and perspective. If not, then see if you could cut away or insert some other shot in between to distract the audience from noticing the dissimilar shots.

Exception

The exception to this practice is where a wide angle must be used to show a subject moving from foreground to background or the other way around. Generally, with significant available light, the wider the lens angle used, the more the picture background is in focus. In other words, the depth of field is greater (Diagram C in Figure 8.6). Additionally, shots of unmatched visual qualities may have to be edited together in this scenario if those are the only takes made available to you.

13. Ensure that Subjects Talking on the Telephone Appear to Be Looking Across the Screen at One Another

Reason

Traditionally, film grammar indicates that the characters speaking over the telephone from two separate locations should be composed so that they look across the empty frame, and from opposite sides. This will generate the idea in the viewer’s mind that they are addressing one another across the screen as you cut from one single shot to the next and back again (Figure 8.7). The subjects’ look room, lines of attention, and screen placements, etc. all combine to engage the audience in the conversation.

Solution

Hope that the composition of the footage for this scene was done in such a fashion. Otherwise, edit whatever material you have because you cannot alter the subject’s placement within the frame unless you use a flip effect and reverse the video image horizontally (provided there are no written words or numbers on the screen that would then appear backward). If both shots are framed correctly, you may even create a split-screen effect with this coverage and have both faces on screen at one time.

Exception

There may be good dramatic reasons to change this working practice. If one person is shot with his or her back directly toward the camera, then the direction of the other person may be changed if the footage allows it. Additionally, if the coverage of each individual shows him or her moving around with mobile phones, then this practice may not apply due to the constantly changing action line of each shot.

FIGURE 8.7 Static shots of a two-person telephone dialogue recorded in two separate locations should be treated as if the subjects occupied the same film space and were speaking to one another in person. Proper framing and look room should be present in the shots. Joining them together in a split screen can be easily achieved.

14. In a Three-Person Dialogue, Beware of Cutting from a Two-Shot to Another Two-Shot

Reason

If you have coverage of a three-person dialogue scene that contains several two-shots, then in all likelihood the central character will appear to jump from one side of the screen to the other (Figure 8.8). A shot taken from Camera Position 1 shows the center person (Character B) on the right-hand side of the screen with Character A on the left. If you now cut to another two-shot from Camera Position 2, then this shot will show Character B on the left-hand side of the screen, with Character C on the right-hand side. This is a screen placement jump cut for Character B and can disrupt the visual flow of the shots and confuse or annoy the audience.

FIGURE 8.8 In this example, three people covered by two two-shots will result in a compositional jump for Character B from frame right to frame left at the cut point. Instead, use any other coverage to separate the connection of the troublesome two-shots.

Solution

Provided other coverage shots are available, cut to a single shot of a person instead. For example, cut from a two-shot of Characters A and B to a medium close-up of Character C. Or, conversely, cut from a medium close-up of Character A to a two-shot of Characters B and C.

You could also cut back out to a wide shot of the entire trio between both of the two-shots, provided there is appropriate continuity. If available and appropriate, you could also edit in a cutaway or insert shot before you return to Characters A, B, and C.

Exception

There are no exceptions to this practice unless the style of editing for this project accepts and encourages such visual jumps.

15. With a Single Subject, Try to Avoid Cutting to the Same Camera Angle

Reason

There is a strong chance that a jump cut would result if you edit two shots taken from an identical or extremely similar camera angle (see the six elements of the cut in Chapter Five). This relates directly to the traditional film shooting practice known as the 30-degree rule, whereby each coverage shot of the same subject or object in a scene should come from the same side of the axis of action and be at least 30 degrees different in camera placement along the 180-degree shooting arc.

In Example 1 of Figure 8.9, cutting from the medium shot at Camera Position A into a medium close-up at Camera Position B could present a problem in the form of a jump cut. Cutting from a medium close-up to a medium shot, however, is less of a problem.

Solution

It would be better to cut to a medium close-up from a different camera angle, provided one was actually recorded by the production team.

FIGURE 8.9 Example 1 shows a cut-in or an axial punch-in. Example 2 shows a more traditional shot option for the cut. A new angle and focal length help to lessen the chance of a jump cut for the audience.

In Example 2 in Figure 8.9, Camera Position B has moved to the right, creating an angle on the subject that is more 3/4 frontal. If a shot from this position were available, the cut to the new angle would be more traditional and the risk of a jump cut would be reduced.

In the case where a shot from an alternative angle does not exist, then a cutaway could be used to separate the medium shot and the medium close-up of the same character on the same lens axis. This cutaway (of something appropriate to the scene) would allow the audience a visual break and the jump cut effect would not be experienced. This practice is more or less acceptable if you cut out to the medium shot from the medium close-up.

Exception

One exception to this practice is when cutting two shots together that are very dissimilar, such as when a great distance is covered between the two shots set up along the same lens axis. Of course, for creative reasons, you could edit a series of cut-ins along the same lens axis to achieve a quick punching-in effect – a zoom without the zoom, as it were.

16. Beware of Screen Placement Issues with an Object of Interest

Reason

Even when the human subjects are on the correct sides of the screen in the coverage shots, the audience will have an additional visual reference, sometimes called the object of interest or the point of interest.

For example, a two-shot of a man and a woman (Shot 1 in Figure 8.10) shows a painting that is framed center screen. Cutting to the man (Shot 2) will show the painting screen left. Cutting now to the woman (Shot 3), the object of interest (the painting) has jumped to screen right. Even though the edit is technically correct, the point of interest jumps, and this can be visually distracting.

Solution

Where an object of interest is evident, either keep it in the same area of the frame, or select the shots that either eliminate it altogether or minimize its on-screen presence (Shot 4).

Exception

An exception to this working practice is where the object of interest is so small as to be negligible, where it is far in the background, or where it is out of focus. You may also find that some other subject in the action of the scene obstructs the object of interest, either partially or totally.

FIGURE 8.10 Much like a person can jump sides of the frame in a three-person back-and-forth dialogue, objects of interest can do the same thing. Tighter shots may hide the object jumping left, then right, and back again.

17. Edit in a Wide Shot as Soon as Possible After a Series of Close-Up Shots in a Group Scene

Reason

It can be easy for the audience to forget the exact location of subjects in the film space, especially during a fast-moving production. After a series of medium shots, medium close-ups, and close-ups, particularly those with out-of-focus backgrounds, it becomes important to re-establish the scene’s and the subjects’ location. If you choose to introduce a series of characters, all in close-up, then you should show them all again grouped together in the wide shot.

Solution

Be careful about editing an entire sequence with only close-ups – unless there is a need to do so.

Even one quick cut to a long shot, showing the relationship of the subjects to each other and to their surroundings, gives a much better grounding to the scene for the viewing audience.

FIGURE 8.11 After a series of closer shots, it may be helpful to show a wide shot to re-establish the scene in the viewer’s mind.

Exception

The exception to this practice is where the location or scene is well known to the audience, such as the main set of a popular TV show.

18. Cut to a Close Shot of a New Subject Soon After He or She Enters a Scene

Reason

This may be the first appearance of this subject and the audience will want to know who he or she is. The audience should be shown the new information as soon as is practical.

A long shot will only show the new subject in relationship to other subjects and to the location, but someone new entering the wide scene needs to be shown in a closer shot to be more properly identified.

Solution

Edit in a closer shot of the subject at the earliest opportunity. This also applies if the character is not new but has not been seen by the audience for some time. Support the audience’s understanding of the story by reminding them of events and people through tighter shots that provide the necessary details.

FIGURE 8.12 Inform the audience by showing them a closer shot of a new character entering a scene.

Exception

The obvious exceptions are when the character is an extra or a “bit” player, needs a delayed introduction for comedic reasons, or needs to be kept secret for narrative purposes.

19. Use an Establishing Shot to Set Up a New Scene’s Location

Reason

The audience not only like to know what is happening in a new scene, but also where it is happening. They benefit from seeing some form of visual “geography” that establishes the relationship between the environment and the subjects in the scene that unfolds there.

Solution

Some form of wide shot – for example, a long shot, a very long shot, or an extreme long shot – will be helpful. This wide shot should serve a number of purposes, such as to give some geography of the scene, to show time of day or season of year, to establish the relationship of the character(s) to the surroundings, and/or to establish a general impression of the movement of the subjects.

In documentary or non-fiction motion media productions, these types of establishing shots should be among the B-roll footage. For any kind of project that lacks these shots in its original, visual material, consider using stock footage libraries or still photographs of locations – perhaps with a motion effect to provide some energy.

Exception

You may opt, for creative reasons, not to show an establishing shot but rather to cut right in to the scene, perhaps in a close-up shot of some element within the set. Then you could pull back and show a wider shot of the location of the scene. This method creates more of an anti-establishing shot. It stresses audio ambience over exterior imagery while you are grounding the viewer in the new location, and makes for a refreshing change. If the scene is shown in closer shots and seems to take place in an unknown location, the actual establishing wide shot could be shown last as a sort of reveal and a surprise for the audience – perhaps for shock, perhaps for comic intent, or perhaps purely as information.

FIGURE 8.13 Using a wider shot to open a new sequence of scenes at a new location can help to ground the audience and provide much-needed information with one image. This holds true for both exterior and interior locations within your story.

20. Use Close-Ups of Subjects in a Scene for the Greatest Emotional Effect

Reason

A close-up of anyone’s face is a very intimate shot. It carries with it a great deal of visual information and, depending on the expression of the face and the context within the story at that point, it can easily sway the audience emotionally. Using such a powerful shot too early in a scene’s development could dilute the efficacy of close-ups when they are used later to make an emotional point or underscore a certain counter-current in the storyline through a reaction shot.

Solution

Save the close-up shot of the character or characters for when the audience will benefit most from seeing the actors’ faces in such intimate detail. The close-up will yield a clearer assessment of a character’s emotional or mental state to the viewer. If the drama or tension of the scene is rising, cutting to closer shots toward the climax will provide the audience with more emotionally engaging visuals. This effect will be watered down if you go to the close-up shots too soon in a scene’s development – or, perhaps even worse, if you allow the energy to dissipate by cutting back out to the wide shot too frequently.

FIGURE 8.14 The close-up conveys much emotional detail. Use where appropriate, but often later in the scene is preferable for the greatest emotional effect on the audience.

Exception

Documentary and news talking-head interviews will be recorded mostly in medium shots and closer. You will have to use these shots right away in the sequence. Often, fictional narrative television and web programming will have significantly more coverage with close shots of individuals due to the smaller screen on which they get displayed. Cutting to such close-up shots sooner in each scene could be encouraged for television and internet programming. Additionally, if the lighting on a close-up of the character partially or entirely obscures the face for narrative purposes (to protect an identity, create mystery, etc.), then these shots should be edited in the sequence as required.

21. Cut Away from Subjects Soon After Their Look Rests upon Their Object of Interest

Reason

A shot depicting a subject looking at some object of interest off screen is the perfect set-up for a reveal to the audience. In general, you would cut to the shot of the object of interest next. The motivation for this edit arises out of the character’s look and initial facial reaction to the yet-to-be-seen object off screen. Once the physical movement of head and eyes has come to a rest, the audience will likewise wish to see what is now being focused upon – hence the cut to the shot of the object which reveals the new information (Figure 8.15).

Solution

The editor hopes that the actor was instructed during production to look off screen and react to some object. He or she further hopes that the actor achieves the look with a final solid head placement and eye-line to some object off screen. It is the solidity of the final look – the focusing of the eyes along a particular line – and a facial reaction of recognition that create the strongest cut point.

Exception

Clearly, if no take of the “looking” shot ends with a solid, strong gaze from the actor, then you cannot cut away at the moment of the eyes’ focus. You will have to find the most acceptable point of recognition on the actor’s face and then cut. Faster action sequences or scenes that involve multiple objects off screen do not necessarily call for a static head and focused eye-line from the actor.

FIGURE 8.15 Allowing the actor’s eyes to lock onto the off-screen object of interest generates a need within the viewer to also see this new object. This motivated cut to the object of interest is often called a reveal.

22. Use J-Cuts and L-Cuts to Smooth Over Transitions

Reason

Straight cuts on all picture and audio track edits can feel rather staccato – especially in dialogue scenes. It can really improve the flow of a scene if sometimes the incoming sound starts under the outgoing picture clip (a J-cut), or, conversely, the outgoing sound carries on under the incoming picture clip (an L-cut).

Solution

Sound bridges are useful both within scenes and between scenes or segments of a video. The idea behind the J-cut stems from real life where a person will hear a sound and then look to see what is making that sound – audio information leading to new visual information. The L-cut allows the audience to acclimate to new visual data while they are momentarily carried forward by the familiar audio that they have already been experiencing in the preceding clip. Rather than an abrupt changeover in both picture and sound information, this staggered approach can smooth over edit points and propel the audience forward with a little more finesse.

FIGURE 8.16 Simply by trimming the audio track cut point for Clip A and Clip B, you can turn a straight cut into an L-cut or a J-cut split edit or sound bridge.

Exception

Some moments of a video, depending on the genre, can actually benefit from the hard, simultaneous cut between picture and sound clips in the timeline. Abrupt changes in audio levels (usually from quiet to loud) can “wake up” the audience with a sudden burst of sound energy. This is often accompanied by a changeover in the brightness of the video clips or the amount of visual movement within the imagery at the same time.

23. Create Continuous Motion Action Edits by Matching Physical Movements

Reason

The audience typically expect continuous motion when they watch a scene from a story that was shot in the continuity style of filmmaking. The movements of subjects and objects would be constant and uninterrupted in reality, so they should appear to have the same fluidity in a movie of this style. The various shots, from different angles and with different framing, should be cut together to present this illusion of continuous motion. The “blink” of the actual edit is masked by the matching movements from one shot of the coverage of the action to another shot of the continuation of that same action. The cut goes unnoticed by the audience (Figure 8.17).

Solution

Perhaps this can be best demonstrated with an example. The simple scene involves a woman sitting at a patio table. As she enjoys the morning, she lifts a mug of coffee and drinks. Shot A is a medium shot of the woman at the table and she lifts her mug of coffee – CUT TO – Shot B, a close-up shot continuing the coffee mug lift and showing the actual sipping of the beverage.

As you near the end of Shot A (the medium clip), you would cut somewhere along the motion path of the woman’s arm rising – not before the arm begins to move and not after it has fully brought the mug up to her mouth. This new tail frame, cut during the motion, will inform you where to begin Shot B.

You may start by trying to match the mug’s position in the first frame of Shot B exactly to the frame at the end of Shot A. This may or may not work. It is often suggested to begin Shot B three to five frames prior to the “ideal” visual frame for “perfect” physical continuity. Those fractions of a second of action are lost on viewers as they acclimate their eyes and minds to the new information on the screen in the second shot. Remember to always back up toward the beginning of Shot A and watch the edit at normal playback speed (scrubbing across the cut will not give you the true timing of the actions even though the object placement may seem correct on the screen at the two frames around the cut point).

FIGURE 8.17 Cutting on the action of subject movement (about two-thirds completed) will most often make for a smoother transition across the action edit. Viewers ignore the matching action cut as they absorb the new information in the second shot.

If there is a jump of some kind (not smooth movement), then experiment with cutting action a little earlier or a little later, and judge for yourself. The Trim Tools in your video-editing application will make this editing process easier. Most continuous action will benefit from trimming just a few frames at either the tail or the head, or sometimes a bit from both.

Exception

Any project that calls for a special visual style, such as jump cuts, or playing with the space/time continuum of actions and reactions, etc., does not always need to follow this practice.

Additionally, if the performance of an actor’s dialogue delivery during this scene is particularly engaging and dynamic, then allowing minor gaps in motion continuity may be fine because the audience will most likely be so attentive to the character’s words that the glitch in motion may go unnoticed.

24. When Cutting a Rise as an Action Edit, Cut Before the Subject’s Eyes Leave the Frame

Reason

A “rise” is any movement of a subject from within the frame to up and out of the top of the frame and then across the edit point in continuous action. In these shots, the camera does not tilt up to properly follow the movements of the subject and the head gets cut off. For example, the subject sits on a park bench and then stands up, someone climbs the rungs of a ladder, or a subject walks up steps. The action edit point could occur anywhere within the actor’s total movement up until the eyes are about to break the top of the frame.

It would be advisable to keep the actor’s eyes on screen for as long as possible in the first shot. The subject’s eyes are the natural focal point of the viewer’s attention. When they leave the frame, the audience lose that connection with the subject. Additionally, with no tilt up to maintain proper framing, the subject’s head is cut off and this just looks odd to the viewer. This gets worse in close shots when the rise occurs very quickly due to the magnification of the head within the shot’s framing.

Solution

A woman is seated at a park bench (Figure 8.18). The edit point in Shot 1 will be when her eyes approach the top of the screen (Frame 1B), cutting to Frame 2B in Shot 2. This may seem only a short distance, but actually the subject leans forward before rising. This happens naturally.

If the subject’s head is off screen when the cut is made (Frame 1C), then the edit will appear to be “late.” If the editor cuts before movement (Frame 1A), so that all of the movement is seen on the medium long shot (Frame 2A), then the edit may be deemed an “early cut.”

In these examples, early cuts are not normally as disturbing as late cuts. Watching most of the action from the second (wider) shot is not so wrong, especially if the woman continues up and out of the frame. However, the late cut example of Shot 1C and Shot 2C presents the issue of what the audience get to look at during the last few moments of Shot 1. Granted this transition will occur relatively quickly, but once the entire head clears the top of the frame, the audience are seeking some new information. They want to see the character’s face again and watch the continuous action of the move.

Exception

One exception to this practice is when the first shot is closer than a medium close-up. It is rather difficult to cut smoothly away from a close-up or big close-up on a rise. An early cut is almost inevitable due to the size of the face within the frame and the lack of physical space for the upward movement.

FIGURE 8.18 Examples of cutting on the rise. Column A shows the medium close-up of the character rising off the bench. Column B shows the medium long shot of the same action. Best practice may be to leave the subject’s eyes on screen for as long as possible and then cut away from Shot 1B to Shot 2B.

25. When Cutting to a Close-Up of an Action, Select a Version of the Close-Up Where the Action Is Slower

Reason

If the action of the close-up happens at the same speed as that of the wider shot, then the speed of the action, as seen on the close-up, seems faster. This is due to the relative size of the object within the closer framing. It is now a large object so it has very little screen space to move within the close-up frame. Any quick or even “normal” movement would appear to happen too quickly because the object has less distance to travel around the screen before it breaks out through an edge. You hope that the production team understood this phenomenon and got some of the close-up takes at a slower speed of object movement.

For example, in Figure 8.19, the subject is picking up a book in the wide shot. The close-up shows the hand also picking up the book. The action on the long shot is at normal speed and the book never leaves the frame. But in the closer shot, the book moves out of the frame very quickly. So, if the close-up action is carried out at the same speed, it seems faster.

FIGURE 8.19 Be aware of speed of action in closer shots where the magnified object’s movement clears the frame very quickly. Shot 1 is a medium long shot of a woman picking up a book. Shot 2 is a close-up highlighting the book’s movement out of the frame.

Solution

You hope that the director has provided an additional close-up with a slightly slower action. The slower version will appear to move at a “normal” speed. If necessary, your video-editing software may have motion effects built in that can slow down a shot just enough to be effective. Be forewarned, however, because a keen audience may easily detect this slight slow-motion effect.

Exception

This practice does not apply to close shots of moving machinery.

26. Understand the Visual Differences Between a Dolly-In and a Zoom

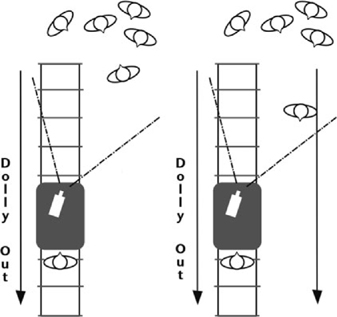

Reason

Many consider a “zooming” image to be a very unnatural visual effect due to its uniform magnification of distant objects. The camera does not move and the lens optically enlarges all visual elements within the frame. It has no change in perspective. The horizon (or far distance) and the middle distance will come toward you at the same speed as any objects in the foreground. As our eyes do not zoom, the “movement” through film space can seem unnatural and stand out to a viewer.

Solution

Unlike a zoom shot, a dolly-in shot (sometimes called a truck-in or a push-in) is considered a more natural movement that will have a perspective change analogous to what our normal vision would produce. The camera lens, like our eyes, is moved closer to the subject, who appears to grow larger while the background remains “further away.”

The two sequences of shots in Figure 8.20 show the difference between the zoom and the dolly-in. Note the differences in size and apparent “nearness” of the doorway awning at the corner of the building in the background frame left.

It is also a common practice for filmmakers to combine lens and camera support movement within a complex shot. A shot containing a zoom may also be used if it contains another camera movement at the same time that helps to camouflage the zoom.

Examples of such shots include:

• a tilt with a zoom

• a pan with a zoom

• a crab dolly with a zoom

• a pedestal or boom elevation with a zoom, etc.

Exception

An example of a non-traditional zoom is when it “creeps,” i.e., when it is so slow that you actually do not realize it is a zoom. Slow zooms during long takes of slowly paced action or dialogue-driven shots will evolve the composition over a longer time and the subtle changes in framing happen so gradually that viewers will most likely not notice as they pay attention to the actors, etc. As an editor, you will find this type of shot relatively easy to cut into the program in its entirety, or to cut up with other reaction shots as necessary, because the zoom will be so slow that cutting on the lens movement will most likely not be noticed.

A zoom in TV news or other “reality”-type programming or sports coverage is another exception as it is more accepted within those genres. Obviously, a detail of the content or action is the motivation to make the zoom.

In addition, a zoom used in a shot without any discernible background, (e.g., a white wall, sky, or flat ocean) might possibly go unnoticed.

FIGURE 8.20 Zoom movements will alter perspectives on the film space, especially the background. The left column shows zoom movement and the right column shows dolly-in movement. Subjects receive similar magnification, but notice the differences in size and proximity of background elements, chiefly that triangular doorway awning seen in the background frame left.

27. Beware of Shots that Dolly Out without Motivation

Reason

A dolly track-out (sometimes called a truck-out or a pull-out) can often initiate a scene to show more of the location, or signal the end of a sequence or a scene. It may precede either a dissolve or a cut to another scene or even a fade-to-black. If no subject movement comes toward the camera initiating the track-out (backward, away from the established angle of view on the scene location), then the camera takes on a consciousness of its own. The audience may not be accustomed to the camera suddenly moving as if it were motivated by its own thoughts or desires (Figure 8.21).

Solution

The motivation for the dolly track-out will usually be included in the shot. In the case where no motivation is evident, or where motivation does not exist in the previous shot, see if the scene can still run without that tracking shot. Typically, dolly shots take a long time and can cost a production a lot of money, so it might not be an option to leave it out of the final edit.

Exception

If this is a visual treatment that has already been established in the motion picture (a free-moving camera with its own “motivations”), then it would be part of the style of the film and, therefore, appropriate to use. Another exception may be when a track-out precedes a narrative jump in time, location, or tempo, or where the dolly-out is the final shot of the production.

FIGURE 8.21 Understand when track-out dolly shots are motivated by subject movement and when they are not. A camera moving away from the location of a scene on its own appears to have a certain consciousness that may not be evident among the other scenes in the program.

28. Select the Best Version of a Pan or Crab Dolly Shot

Reason

Dolly moves and panning shots that follow talent movement are often rather tricky to record during production. Several variables and different crew members, plus the talent, are involved in their creation and it is easy for things to not quite flow as intended. When reviewing the takes of complex or developing shots like these, watch for the one with smooth camera movement, adequate lead room for the subject’s movement, proper focus, and good pacing. An audience watching a bumpy move, a bad composition, or a blurry moment in the shot may have their viewing experience compromised.

Solution

Again, an editor cannot change the quality of the shots that he or she is given, but must work with the material presented as best as possible. Seek out the best takes that are available that meet the criteria for such a shot. In some cases, you may use just the good portions of multiple takes and stitch them together with some cutaways. If there are a number of takes, a shot should be selected where the camera has “led the subject” (i.e., where there is more frame space before the subject than behind – as shown in Figure 8.22), has good focus throughout, and is smooth, with good pacing appropriate for the entire scene.

Exception

The exceptions to this practice may be found in fast-paced action shots, or even handheld cinéma vérité style shooting where the slightly jerky camera adds to a sense of immediacy, danger, or reality.

FIGURE 8.22 Select the crab dolly shots that provide stability, good focus, and ample lead room for talent movement.

29. Begin and End Each Pan, Tilt, or Dolly Shot on a Static Frame

Reason

Cutting into a shot that is already in motion can cause a jump cut effect within the mind of the viewer. Cutting away from a shot that is in motion to a static shot can also be jarring, but it may be more acceptable if the narrative calls for such a visual treatment.

Solution

The production team should provide pan, tilt, and dolly shots that begin with a static frame, move for the duration of action, and then end on a static frame. This is not always the case, but as an editor you would hope for this scenario (Figure 8.23).

If Shot 1 is a static, simple shot and you wish to cut to the complex moving shot (Shot 2), then you should keep those static frames at the head of Shot 2. This allows you to cut from static frames to static frames. The audience will treat this as an invisible edit because movement comes after the static transition.

FIGURE 8.23 The locked-off camera at the end of Shot 1 will help to create an invisible cut into the static start frames in dolly Shot 2.

At the end of Shot 2, after the tilt, pan, or dolly move, you would most likely wish to finish that shot on a static frame as well. You can then cut to Shot 3, the next static shot. This again provides an invisible edit for the audience: static to static.

Exception

If you decide to string several complex movement shots together, perhaps in an action sequence, then you can cut not static to static but moving to moving to keep the pace of the action going. One thing to watch out for in this scenario, however, is the speed of the camera movement and of the subject movement within the shots that you are cutting together. If the speeds are not matching or at least similar, this can cause visual interruptions to the flow of images and the audience may sense the shift in tempo.

30. Avoid Editing a Stationary Simple Shot After a Moving Complex Shot of the Same Subject

Reason

A cut from or into a camera movement may appear as a jump to the eye. A subject who is in motion in a dynamic Shot 1 but who is then shown as stationary in a static Shot 2 will appear to jump in time or space.

Solution

Take, for example, a subject who is moving across film space (right to left). The shot calls for her movement to be paralleled by a crab dolly (Figure 8.24). It is possible to cut to a static shot of the subject, but only when the subject has cleared the frame for a reasonable time prior to the cut. The end dolly of complex Shot 1 should be static prior to the cut to the simple static medium Shot 2 of the stationary subject.

There are two reasons for this. First, you may want to finish or clear the action in the shot before cutting out of the shot. Second, the pan or dolly is likely to be a complex shot. As such, like a developing shot, it should have a beginning (the initial static frame), a middle (the pan with another movement, tilt, or zoom), and an end (the final static frame).

The preferred place for the cut is on the static frame, where the camera is not moving even though the subject may be.

So, unless the camera stops, and/or the subject stops, and/or the subject is no longer in the frame, then it is better if the next shot does not show the same subject as stationary.

Exception

There are many scenarios where this guideline may be overruled. Depending on the material involved, the program type, the pacing of the footage, and the pacing of the scene being cut, you may choose to experiment with cutting into and out of action and stationary shots. Most likely, however, you will succeed in proving to yourself that it just does not look or feel right the majority of the time.

FIGURE 8.24 Allow the dolly action and subject movement to finish before cutting to a static shot of the same subject who appears stationary.

31. Avoid Cutting Pans and Tilts that Reverse Direction at the Cut Point

Reason

Screen direction and flow of motion have a continuity of their own. When object movement motivates a leading camera pan or tilt in Shot A and then Shot B reverses that object’s movement, a visual “crash” will occur at the cut point. Screen directions will have suddenly switched and the viewer will feel this reversal as a disorientation of visual flow.

Solution

You hope that the production team maintained screen direction and visual continuity while they were shooting the coverage for the scene. If you do not have a continuous direction in the footage between Shot A and Shot B, then you can either not use Shot B or insert some other shot between the two to distract viewers and re-orient their sense of movement so that when Shot B comes on the screen, they are not disturbed by the alteration in the pan or tilt’s direction of movement.

You can also employ a flip effect to switch left/right direction of movement (if no text or numbers appear on the screen during the flipped shot).

Exception

As a creative practice, it may be worthwhile, given the appropriate topic in a program, to attempt to marry reversing pan or tilt shots to cause the visual crash for effect. A story with strong conflicting themes, an experimental film, a non-fiction promotional video, or a music video may exhibit such crash cuts.

32. Avoid Crossing the Action Line or the Screen Direction Will Be Reversed

Reason

Refer to the section on screen direction in Chapter Four.

In Diagram 1 of Figure 8.25, a conveyor belt moves boxes from frame left to frame right as seen from Camera Position A. The shot itself is shown in Image 2. If the line is crossed – i.e., if the next shot is taken from Camera Position B (see Diagram 1) – then the belt appears to be moving the boxes from right to left (Image 3).

Solution

Select shots from one side of the line only, or use a neutral cutaway between the shots if the line must be crossed. A close-up of part of the machinery not showing the belt movement would be suitable. In documentary or reality programming, you could also use a wipe to get from one side of the belt to the other.

FIGURE 8.25 The moving machinery establishes an action line and a screen direction. Shooting from the opposite side of the initial 180-degree arc would reverse the flow and flip directions, so try to avoid editing such conflicting shots.

Obviously, if the camera were to move from one side of the belt to the other during the shot, a jump cut would not appear, but the direction of the belt would still be reversed.

Exception

Shots (especially B-roll for a non-fiction program) recorded from the opposite side of the action line could certainly be edited together in a fast-paced montage sequence.

33. Avoid Cutting an Action Edit from a Two-Shot to Another Two-Shot of the Same Subjects

Reason

An action edit requires closely matching continuity of placement, movement, and general performance. With two moving subjects involved in the shots, it becomes that much more difficult for the editor to match the movements of each (Figure 8.26).

Solution

When cutting out of the two-shot, cut to a closer shot of one of the two characters, cut to some form of reaction shot, or possibly cut to a very long shot if it exists among the footage. Trying to match the action for all concerned parties would be difficult if you went for another two-shot from a different angle.

Exception

A much wider shot of the entire environment, including the two subjects, is more likely to hide any incongruous body movements, etc. Any event shot with multiple cameras may also avoid this issue because action would match across a multi-camera edit. If the action concerned is frenetic enough (a fight scene, extreme sports, fast dancing, etc.), then cutting from two-shot to two-shot may be perfectly acceptable with that sort of energy, confusion, or movement, although it would still appear as a jump cut.

FIGURE 8.26 Cut from the first medium long shot to any other coverage shot except another medium long shot still showing all subjects. An unwelcome jump cut will result if you do not follow this guideline.

34. Allow a Subject to Exit the Frame Completely Prior to Showing Him or Her Entering the Next Shot

Reason

In the “classic” screen-direction continuity action edit, it is advisable to allow the subject to leave the frame entirely in Shot A – especially when Shot B shows that same character, but at a new location and at a later film time. It is customary to cut away once the actor’s eyes have cleared the edge of the frame, because the face and eyes of the actor are what the audience will be watching, but showing the whole body clear the frame allows for a cut to any new location with no need for matching continuous body placement. Screen direction may still be maintained, however. If an emotional note has just played out in the scene and the characters depart, then you may want to linger on the empty location in Shot A for a beat or two to allow the audience time to soak in that quiet moment.

Solution

As seen in Figure 8.27, Shot A ends with the body no longer visible just prior to the cut. Introducing Shot B, the viewer will find an empty frame of a new location, and possibly a new time, to analyze. Then the actor or object will enter the frame. This allows something of interest to the viewer to remain on the screen at all times.

FIGURE 8.27 If you wish to jump a subject in place and time at a cut point, allow him or her to clear the frame entirely and have the new or incoming shot start empty. The new empty frame of Shot B will provide new visual data (place and time) to the viewer before the character strides in from the edge of the frame.

Exception

Extremely fast-paced action sequences may allow for portions of the subject’s body to remain on screen at the end of Shot A and appear already on screen at the start of Shot B. The increased speed of subject movement covers the jumps in subject screen placement at the cut point. If the pacing is too slow, however, the portions of the subject visible at opposite ends of the screen might cause a jump cut.

35. Maintain Screen Direction Across an Action Edit

Reason

This is a very basic practice for any moving subject within the accepted film grammar. The continuity of screen direction, even across the transition, should be constant. It helps to establish the directions of left and right within the film space and keeps the audience properly oriented within this fictional landscape (Figure 8.28).

Solution

The appropriate coverage with proper screen direction should be provided to you for the edit. If you do not get footage with proper screen direction maintained, then you had better seek a diverting cutaway shot to place in between shots. You may also choose to establish this “inconsistency” as a visual motif for this character or for the overall project.

Exception

The exceptions to this practice are when:

• the direction is actually seen to change on screen;

• there is a suggested change of direction on screen followed by a cutaway;

• the change of direction is caused by the cutaway (e.g., in the haunted house, running in one direction, seeing the ghost, then running the opposite way).

FIGURE 8.28 Screen direction of moving subjects should be maintained across action edits. (Photo credits: Zach Benard)

36. Avoid Making an Action Edit from a Long Shot of a Subject to a Close-Up of the Same Subject

Reason

It is a jump cut to be avoided, unless a shock effect is required or unless the character is recognizable and identifiable in the long shot and there is not much action to physically match when the close-up shot cuts on screen.

Solution

In Example 1 of Figure 8.29, the overhead schematic shows a man walking up to a car in a wide shot. He stops beside the car door to unlock it with his key. In two shots, it may look as it does in the images in the example.

It will cut together, but it is too much of a jump to the eyes of the audience, and the visual reaction may be, “Who is this new man?” or “Where have the first man and the car gone?” Unless this character and vehicle are extremely well known to the viewing audience, this edit can break the visual flow and is therefore discouraged.

It would be better to use three shots, as shown in Example 2: (1) the wide shot to set the scene; (2) the medium long shot at a different angle to show more details; and (3) the close-up shot from the first angle. The result of having the extra shot between the wide shot and the close-up is to make the scene flow more smoothly. Now the audience know who the man is, where he is going, and what he is doing.

Exception

This practice may be overruled if the established editing style of the program calls for such a visual treatment of the material.

FIGURE 8.29 If the coverage has been provided, you may find it beneficial to cut three shots (long, medium, close) rather than just two (long, close) so that the audience follow along with this series of action edits. (Photo credits: Anthony Martel)

37. Beware of Editing a Cut-to-Black Followed by a Cut-to-Full-Picture

Reason

A straight cut-to-black is a very serious statement in narrative film production. Because it is an abrupt change-over from visible picture to full black, it carries with it a very dramatic weight, especially when you cut straight out of that black to a new, full image in the next shot. Reserve this bold treatment for an appropriate project whose visual style can absorb this dramatic editing practice.

Solution

Some possible combinations for the end of a sequence or scene and the start of another are:

• cutting to the next picture;

• dissolving to the next picture;

• fading to black and then fading up to the next picture (dipping to black);

• cutting to black and then fading up to the next picture;

• fading to black and then cutting to the next picture.

FIGURE 8.30 A hard cut from a full picture to a full screen of opaque black can be jarring for the audience. Treat this dramatic transition with respect and use it appropriately.

Exception

The cut-to-black and cut-to-picture are used to break two entire programs, two productions, or two complete items from each other, or for a very dramatic effect. Cuts-to-black are often used in editing feature film trailers because the shots that are joined together to advertise the movie were not meant to be joined together and cuts-to-black add to the drama and mystery of the story. Also, the cut-to-black may quickly lead into a title (typically white font over black, opaque background).

38. Take Advantage of the Transition Point that Natural Wipes Offer

Reason

Natural wipes occur any time that an object moves past the camera lens and momentarily blocks the composition of the frame before it clears out of the way. The movement (typically horizontal, but sometimes vertical) provides the perfect motivation to make a cut or a wipe to a new shot in the same scene, or to transition into a new scene.

Solution

Really thoughtful filmmakers will actually pre-plan the talent blocking of main characters, or more often “extras,” to create the natural wipe moment for the editor to use. Other times, a simple happenstance like a van driving through the foreground of the shot on a long-lens exterior set-up can provide the motivation and the physical “image blocker” for the editor to create the natural wipe on his or her own initiative.

Regardless of who constructs it, a natural wipe is “natural” because it occurs during the shot while it is recorded – the wiping of the image on screen is inherent to the footage. Sometimes, during a complex dolly shot, the camera may crab past columns or pillars in a hotel lobby or a parking garage structure. Even though the objects are solid and unmoving, the camera’s movement past them will create a natural (solid vertical) wipe across the recorded images. These may become convenient or clever transition points for the editor to use (Figure 8.31).

It may be helpful to have several of these natural wipes within one scene but certainly within the entire motion media piece, as only one may stand out as awkward or uncharacteristic of the established visual style of the program. Multiple natural wipes create a visual motif for the show.

Also be watchful for production footage that may allow for (or require, if scripted that way) a natural wipe that occurs on vertical camera movement. A camera may rise up in Shot 1 (via a tilt, a jib arm boom, a crane, etc.) and move past a solid horizontal object, such as a ceiling, the wall over a doorway, heavily leafed tree branches, or even a star-filled night sky. Shot 2 of this mini-sequence would typically also have matching upward vertical movement, such as up from behind a desk or counter, or even “through” the floor. Join these two shots together to make it seem as though the camera has gone “up” to a new place, in both space and time.

Exception

Just because a natural wipe occurs within the footage, it does not mean that you must avail yourself of it and cut or wipe at that point, especially if it does not add to the overall scene or story flow.

FIGURE 8.31 An editor can take advantage of a natural wipe within the footage and either cut or wipe to a new shot at that time.

39. Take Advantage of the Transition Point that Whip Pans Offer

Reason

Much like the natural wipe, the whip pan (or flash pan) offers a very convenient and visually interesting motivation to transition from one shot to another. If planned by the filmmaker ahead of time, the fast motion blur generated at the end of a shot as the camera quickly spins horizontally will match with a corresponding motion blur at the start of another shot that is supposed to follow. The editor will join the tail blur of Shot A to the head blur of Shot B and the illusion, when watching the transition play itself through, will be that the motion of the blurring whip hurtles the viewer into a new location, time, or entirely different scene.

FIGURE 8.32 An editor can take advantage of the whip pan contained within two clips that were planned to be joined in this way. If no such whip pan occurred in either clip, then most video-editing software allows you to add blur effects and an editor could create the transition from scratch.

Solution

These whip pans (and, much less frequently, whip tilts) are usually designed and shot on purpose by the filmmaker during production. Unless there is a great deal of handheld footage that whips quickly left or right, then there will be little opportunity for an editor to create his or her own whip pans, although editing software may provide a cheat with some transition blur effects. Highly stylized shows or those with frenetic space/time jumps (like children’s programming, travel shows, or home & garden DIY shows) often employ these constructed pan/blur shot transition effects in post-production.

Exception

Not all whip pan transitions will play correctly. The tail of Shot A and the head of Shot B must be whip panning in the same direction and roughly at the same speed for this transition trick to work.

40. Do Not Use Video Track Dissolves During a Dialogue Scene

Reason

Dissolves typically represent a passage of time between the two video clips that are joined by that transition effect. Dissolves are also associated with a slowing of story time or a blending together of related visual elements to create a more profound, romantic, or otherwise “emotional” moment in the story. Dialogue scenes, typically, happen at one moment in continuous story time and should not need a transition effect to join the coverage shots together.

Solution

Straight cuts will most often be your safest bet when it comes to editing together the coverage shots of a dialogue scene. The pacing of the conversation is set by the timing between the video/audio clips of each character saying his or her lines or reacting to the lines of the others present. Time is usually immediate and continuous. A dissolve would suggest to the viewing audience that a more significant passage of time has somehow elapsed between clips. Additionally, as dissolve effects also act like audio cross-fades, there is a risk of compromising the outgoing and incoming lines of dialogue on the associated audio tracks.

FIGURE 8.33 Stay clear of using dissolve transition effects between dialogue coverage shots within a single scene, as shown in the first five images above. Unless the dialogue happens across a very long span of time, just use straight cuts within the dialogue scene edit.

Exception

Using dissolves to join video clips within a dialogue scene may be appropriate if the dialogue scene actually happens across a longer period of time. Example: Two friends lounge around their apartment on a lazy Sunday afternoon – only speaking occasionally – and the dissolves cover up the gaps in time between their spoken words to one another. It may also be appropriate to use dissolves during a dialogue scene if the scene also contains a short montage sequence of the subjects involved in the conversation simultaneously doing things and speaking across a longer period of time. Otherwise, stick to straight cuts.

41. Use a “Soft Cut” or Mini-Dissolve to Mask a Cut in Interview Footage

Reason

It is inevitable that an editor will have to cut down or in some way condense or “clean up” the spoken-word responses of an interviewee. This extraction of unusable words and picture will often result in a jump cut for the image. If the editor is lucky enough, the person being interviewed moved very little while speaking on camera in his or her medium shot or MCU. A short dissolve effect can smooth over this minor visual discrepancy.

Solution

Rather than using B-roll or some other cutaway to layer over the very subtle jump cuts, the editor may use a two-to four-frame dissolve across the cut to quickly but gently morph the two almost exactly matching video images of the speaker. A dissolve of such a short duration will either go entirely unnoticed (if the talent remained very still) or appear as a “soft cut” or minor melding effect rather than a hard jump in picture alignment.

Exception

Obviously, if the interviewee changed his or her body positioning or facial expression too much at the cut point, the dissolve, no matter how brief or long, will not successfully morph the two video clips together. A B-roll clip over audio would be preferable, or perhaps a noddy of the interviewer, if that is how the show is constructed.

42. Use a Dissolve Between Simile Shots

Reason

As you may know, a simile is a comparison of two unrelated subjects using the words “like” or “as” (e.g., “She’s as tough as nails”). Two shots that may not have anything in common within the context of the present scene or story can behave like a simile. The dissolve will unite the two different shots and a new meaning is created in the mind of the audience. A straight cut would not unite the subjects of the two different shots as blatantly; therefore, the audience might not understand the filmmaker’s “literary” intentions. Although a very old and slightly heavy-handed method of visual storytelling, the dissolved simile shot is still effectively used today, particularly in comedies and animations.

Solution