Chapter 1. ECM Defined

In this chapter, we will lay out the fundamental building blocks of ECM. This will help you understand at a high level what you will need to include as part of a comprehensive strategy for managing content in SharePoint. Almost anyone can create a server farm and then create a site collection and start adding content to a document library. Typically and unfortunately, that’s how most SharePoint projects begin to fail. What you will gain from the following sections is a much broader scope of ECM to help you prevent this from happening.

What is Enterprise Content Management?

Enterprise Content Management (ECM) is not a technology, and SharePoint is not an out-of-the-box ECM solution. These two statements contradict what some have thought to be fact and the marketing slicks and PowerPoint presentations so many of us have seen. You might be asking yourself, “What gives, we bought into SharePoint so that we could have an ECM Solution?”

ECM is a set of practices, processes, and methodology that make the technology morph into the most effective way to store, secure, and consume content. SharePoint is a platform, a grab bag of features, and technology that can be molded into a fantastic ECM solution.

ECM is also not moving what has been done in shared drives to a web-based modern platform. Consider how shared drives evolve, how much file duplication and organizational chaos is typically found in shared drives accessed by a community of users. It is extremely hard to find anything resembling structure. Ask yourself the following questions:

Does your company have a documented File Naming Convention policy?

Do the Shared Drives you work with follow a common Directory naming structure?

Can you easily navigate another department or workgroups Directory structure and find a file?

Most will answer no to these questions, and when asked in a group setting these questions usually provoke eye rolling, scoffs, and jeers. The organization and planning of Shared Drives happens in real-time during content creation. This is often impounded by busy workdays, staff changes, and different personal organizational strategies. Ultimately, this approach is not considered a solution for proper content management.

One must acknowledge that unplanned ECM is the process of taking this same structure and lack of planning and modernizing it. Simply doing a one-for-one transposition of the Share Drive into SharePoint results in an even more rapid use of a very bad system.

ECM is the opposite of this; it requires up-front planning and practical application of information architecture. It assumes a standardization of proven methods for capturing, naming, and storing content. In the past, this required a lot of effort and thought on the part of the user. But more and more, technology is taking over for the unfriendly pieces.

In most cases, the information stored in an ECM system is used to support the primary corporate data found in traditional line-of-business (LOB) systems, such as contract management, human resources management (HRMS), customer relationship management (CRM), or enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. You can commonly find “ECM solutions” with content not attached to LOB applications. Usually, this is a sign of bad ECM, but there can be exceptions. An increasing number of ECM systems are now being used to drive complex LOB activities because people often end up looking for an important document or record to answer a question or to complete a business transaction.

It often takes organizations several failed attempts to realize that without proper ECM no platform can succeed as a content management system. And without a platform with the right set of features, and end-user ease-of-use ECM can’t succeed. The core feature sets of an ECM solution are as follows:

Storage of documents

Document viewing

Document editing

Document security

Metadata model

Versioning of documents

Check-in/check-out of documents

SharePoint today lends itself very nicely as an ECM solution, but that has not always been the case. SharePoint has evolved to provide all the necessary components of an ECM solution, capable of facilitating the complete life cycle of content management. Prior to SharePoint 2010, you could not implement a structured system that would be considered a suitable tool for large scale ECM.

Starting with SharePoint 2007 MOSS, core ECM functionality outlined above was brought into the platform. While SharePoint 2007 could be molded into a reasonable ECM solution for small business, it missed some core functionality in the following areas:

eDiscovery

Electronic forms

Records declarations

Consistent metadata models

Business process management

User and service level audit logs

Compound documents

With SharePoint 2010, this functionality was introduced, and SharePoint was finally a full-blown ECM solution capable of delivering at almost every level. SharePoint 2010 was still lacking in a few areas, such as more robust business process management, document auditing, information architecture, and capture for document imaging. In these cases, third-party solutions appeared out of the Microsoft Partner community and took the 90 percent to 100 percent. We will highlight some of possibilities for widely used third-party solutions that you will want to evaluate, depending on your specific project requirements.

Note

In this book we will focus on ECM related features. While SharePoint can be used for many information management use cases we will not be including or highlighting areas like Business Intelligence, Web Content Management, or Social Collaboration.

With the release of SharePoint 2013, the following additional features are included:

Disposition of sites

Federated eDiscovery

These are two desperately needed ECM tools we will discuss later. SharePoint 2013 also brings some new challenges. The new user interface is better for user adoption but trickier from a governance standpoint. For example, the new “Share” feature, when not properly governed, will cause uncontrolled propagation of site security. Remember SharePoint sprawl, mentioned in the Introduction? The rapid adoption of the Share feature without governance can aggravate sprawl. We will discuss this in greater detail later.

Now that we know that SharePoint 2010 and, more importantly, SharePoint 2013 offer the complete feature set of ECM and then some, we can discuss how organizations can leverage SharePoint as a complete ECM Solution.

A very common misperception about ECM in SharePoint exists with organizations that believe that, by using team sites and collaboration features or by uploading content from shared drives, they are performing ECM. This simply is not the case. These are manifestations of the same bad content habits in a more modern way. This points to one of the primary reasons that ECM projects in SharePoint fail.

Speaking the same language is a common issue and is the trickiest to identify and mind-bogglingly hard to address. Very often, knowledge workers who request the need for technology for more efficient document processes do not possess the knowledge to ask the right questions of the IT professionals who are responsible for delivering a solution.

To mitigate this, many organizations are utilizing the role of business analyst to bridge the gap between user requirements, IT implementation, and operational benefits to the organization. This role can be justified, but return on investment (ROI) can be hard to measure in terms of hard dollar costs versus savings. The ROI for a position such as business analyst is best determined by looking at the soft costs and opportunity costs of getting it right the first time.

Too often, organizations look only at raw capital expense put into deploying ECM, which is the cost of employee time, professional services, hardware costs, and software licensing. They don’t factor in what it will take in terms of change management, user adoption, and the implementation of new policies and amendments. In some cases, the deployment of a SharePoint ECM solution can require changes to job function or description for certain aspects of department operations for individual roles. These are just some of the areas where a business analyst adds tremendous value.

As you can see, the communication gap is not a trivial issue. It requires admission from both the end-users and IT that they are not communicating and perhaps don’t know how the organization operates today. And it even sometimes requires an individual just to manage the requirements gathering and communication.

We have defined at a high level what ECM is, why SharePoint is an ECM solution, and the problems organizations face when taking the SharePoint platform and configuring it to deliver a complete ECM solution. Before we go further let’s dig into the details of the ECM components.

In this section of the book, we will look at the definitions of each component of the ECM stack, and in later chapters, we will examine the full details about each component’s use and implementation in SharePoint.

The ECM stack

We started this chapter telling you that ECM is not a technology, but rather a methodology. This implies that to execute on those methodologies there must be some collection of technology that can do it. The ECM stack is where we stop talking about ECM as a single comprehensive object and start breaking it into its pieces. It’s in the pieces that we align the methods to technology.

The ECM Stack includes all the components of an ECM solution. It is sometimes referred to as the document life cycle. The document life cycle is defined as all possible stages that a document can encounter in its life. The primary stages and components are shown in Figure 1-1.

First comes the Capture stage, which puts the content into the system. The next stage, Store, focuses on storing content, which is predominantly achieved automatically with technology. This is the proper committing of the captured content to the system and is both the logical and physical storage of the content and associated metadata. These two stages feed the ECM system with appropriate content. These stages are considered by most knowledge workers to be the least beneficial to their operation, but without them, knowledge workers have nothing to execute on. It’s in the Manage, Deliver, and Process stages where the real value of the content becomes obvious.

We have found that in user adoption it’s a lot easier to convince users to engage in the management, delivery, and processing of content than in the Capture and Store stages. However, without good capture and storag e of content, effective management, delivery, and processing can’t happen. Later we will discuss strategies for user adoption.

The goal is to spend most planning effort on the quality of the Capture, Store, and Manage stages so that very little effort is required for the Delivery, Process, and Preserve stages. Arguably, the lion shares of the planning for ECM are in the Capture, Store, and Manage stages, while the Delivery, Process, and Preserve stages should be nearly effortless, with good content being put into SharePoint.

We have laid out the document life cycle in Figure 1-2. The diagram is laid out to signify two additional aspects. First, on an X-axis, we have outlined features in each of the document life cycle stages and listed them in order of the most commonly used features in SharePoint to the least commonly used. Second, on a Y-axis, we have ordered each document life cycle according to the amount of planning and configuration effort that should be placed on each stage.

It’s important to think of these stages, beginning with Capture and ending with Preserve, as having “downstream” effects. What happens, the good and bad, while capturing content directly impacts the quality in the Deliver and Preserve stages. If content is captured and identified inconsistently or if a minimalist approach is taken to applying metadata, the ability to find the content will be greatly diminished.

While the greatest benefits to the majority of users is found by searching and finding content in the Deliver stage, the understanding and adherence to the “downstream” concept will ensure that you take capture seriously. The proper attention to detail in each stage will ensure successful results for knowledge workers when they are searching, processing, or managing content. We will define each of these document life cycle stages in this chapter.

Ultimately, these components align to a feature or combination of features in SharePoint. These technologies/features/aspects combine to make the overall ECM solution. Some deployments can have additional components, and at the later stages of the ECM stack, for example, some organizations can omit preservation and eDiscovery. This inclusion of these later stages is usually driven by specific business needs or regulatory compliance requirements. We find that, for the most part, all organizations will or should deploy some aspect of all these stages.

As we said earlier, each SharePoint component aligns to a feature or combination of features. In later sections of this book, we will explain the alignment and provide examples. Now let’s look at each stage in more detail.

Capture

Think of Capture as grabbing information: grabbing it from existing content stored elsewhere, grabbing it from the minds of its curators, or grabbing it from one format and transforming it into another. We capture content constantly without knowing it. Even the process of writing this book is a form of “born-digital” capture.

Capture is the process of preparing, collecting, and indexing content before being stored in an ECM Platform. Capture into SharePoint can happen in the following six distinct ways, ordered by most common to least common:

Without the Capture stage, content does not get into the system. Often this stage is transparent to users because they do it so frequently that they do not realize they are doing it.

This can cause problems in the planning stages of ECM deployment. As depicted in Figure 1-2, Capture is the second-most used stage in ECM, and requires the most planning. We all recognize that this is step one, so failure here results in failure in any downstream stages.

As one of the primary goals for this book, we want to make sure that your ECM team is speaking the same language, so let’s look at the specific types of content capture so that we are all on the same page.

File upload

File upload is the most common way users contribute content to SharePoint. Here we are mostly referring to ad hoc user-driven file upload, but the mechanism can also be used in bulk either by a user or by an unattended script.

Users are most accustomed to browsing to a local file location, selecting the file, and uploading it to a designated space in SharePoint. It is one of the slowest capture processes, but it usually results in the greatest quality of content and metadata.

Primarily performed as a singular activity, based on immediate needs to share or manage a document collaboratively with other users, the file upload method is rarely used to bulk load content into SharePoint. Although users might attempt to do so, it is not recommended.

Document uploading can happen by both browsing to a local folder or network directory and selecting a document(s) to upload. In addition, users can simply drag files onto the document library web interface.

Note

There is a SharePoint user interface limitation of 100 items for bulk operations in the web interface. You can use scripting tools such as Windows PowerShell to perform bulk-loading operations for larger volumes of content.

Organizations can elect to automate the initial load of content into SharePoint, leveraging either Windows PowerShell scripts or migration tools. In later chapters, we will explain both the risks and the benefits of this approach.

One key element of the manual document upload is the process from the users’ perspective. Where are they finding the content? My Documents? A Shared drive? This could highlight some issues that you certainly don’t want transferred over. What are they uploading? Certain file formats don’t belong in ECM, so do you allow your users to upload anything they have access to? What metadata must they complete for a successful upload? We will address these issues in detail in the next chapter.

Microsoft Office documents

Office documents are a born-digital method of capture. These documents have never known a physical existence. This comes with a lot of advantages. This is when a user creates a document in the Microsoft Office suite (PowerPoint, Word, Excel, and so on), which supports the saving of documents directly into an accessible document library.

The advantages of the born-digital method are improved capture accuracy and, most importantly, ease of use. In this mode of operation, SharePoint libraries are “save as” locations for content. Using Office as a client application to contribute content to SharePoint is also a solution that most end-users embrace, because it’s similar to how they have always worked with content.

This encourages knowledge workers to adopt habits leading them away from the storage of content in “My Documents” and “Shared Drives,” which is one step closer to better capture. However, this approach works best when knowledge workers are located within the corporate firewall that is connected to the farm 24/7. Lapses in connectivity can cause problems with upload, versioning, and, more painfully, user adoption.

Proper user training can help with this, and SharePoint “Workspaces” is another alternative. Workspaces is a client Office application that allows content saved in a specific location to be automatically uploaded to SharePoint. Conversely, it allows the viewing of SharePoint Libraries as a folder on your desktop. This is very similar to “Explorer view” and, for the purposes of this book, is considered the same tool.

While Workspaces and “Explorer view” can be used for project portals and personal file repositories, they should not be used for ECM. From a technical point of view, the functionality in Workspaces actually allows the bypassing of proper ECM functionality such as managed meta data columns. From a strategic point of view, if you offer users Workspaces, they are encouraged to live in a My Documents type structure and not a proper ECM. Give the users Workspaces, and you will never be able to take it away.

While many Office documents are manually created, we recommend coaching users to create documents in Office that are saved directly to SharePoint Libraries or, even better, to create content by using built-in Office Web Applications.

Native SharePoint documents

The second type of born digital document is the native SharePoint document. Native SharePoint documents are those documents created without the use of an external client. They very often are Office documents with the addition of blogs, wikis, and pages. For documents, this is done using a feature in SharePoint called Office Web Applications OWA.

Note

Office Web Applications is an add-on in SharePoint 2010 and SharePoint 2013 that allows users to create content in-browser instead of using a client application. It requires Office CALs, and it has some limited functionality compared to client applications. In most cases, it is all a typical knowledge worker needs.

SharePoint now supports the authoring of documents directly in the browser. The majority of the required functionality found in Microsoft Office client applications can be found inside the browser, making content capture of 90 percent of documents very easy to perform directly in SharePoint. Today, this is not the most commonly used form of capture; however, it is the future and the desired method to guide users toward.

As we look to the future of ECM, natively born-digital documents will take over, shortening the time to capture, increasing the accuracy of content capture and its metadata, and being more acceptable to end-users. The challenge of this approach is to make sure that an organization is current in browser and operating system support.

We now move to types of Capture that are more use-case specific and sometimes omitted by organizations.

Electronic form capture

Electronic form submission is one way to get user content into SharePoint. The process enables individuals to complete online forms often referred to as e-forms, and the results of form submission are saved directly to SharePoint. The person completing the form very often will not have access to the form submission content nor necessarily be a named user in SharePoint.

The preferred approach to electronic form submissions in SharePoint is the Microsoft product called InfoPath, because it is a tightly integrated electronic form solution. However, it is also possible to leverage third-party or custom e-form solutions. We will include references to additional resources that can be used for e-form solutions in SharePoint later in this book.

Note

Because individuals who submit forms are most often not the consumers of content in this capture scenario, security is a primary concern. Often, it’s important that submissions are not accessible to submitters.

One of the most neglected aspects of form capture is form design. Without good electronic form design, the information entered into the form rapidly diminishes in quality. Because electronic forms are one of the best ways to capture structured information and metadata, we encourage organizations to spend considerable time on the usability, presentation, and transformation of their forms.

For purposes of this book, discussion of the specifics of e-forms and InfoPath will be omitted. Rather, forms will be highlighted as a way to get content into SharePoint.

Document scanning

Often, documents are not born digital. They begin as physical entities, but they need to be a part of the ECM system just as critically as born-digital documents. The process of capturing this content is called document imaging or document scanning.

This process occurs in three primary ways: ad hoc, departmental/distributed, or production capture. The process also can include image-only capture or capture with intelligent conversion technology.

The owner of the content at their client workstation performs ad hoc capture with an attached document scanner. Departmental/distributed capture is an extension of this, but shared document imaging stations are usually shared among several knowledge works. Finally, production capture focuses on centralizing all capture operations, controlling the indexing, and performing advanced processing and data collection functions in a predictable manner.

How organizations pick one type of capture over another depends on the document maturity of an organization or their own structure. Later we will go into detail about how the various types of capture can be incorporated into SharePoint. While SharePoint does not have natively built-in scanning functionality, there are several ways to incorporate ad hoc and departmental scanning. Production scanning is often considered as a process outside of SharePoint.

Content streams

Sometimes content is not created by a user but rather by another system. “Integration” is a rather broad term that describes connecting disparate systems. For purposes of ECM, we will define a specific type of integration where only content and metadata are transferred from outside SharePoint into SharePoint and refer to it as content streams.

A content stream can come from any electronic source and is defined as the ingestion or publishing of metadata and content via some standard such as Windows PowerShell, REST, XML, and RSS. An example would be the consumption of news feeds inside of a SharePoint page or the publishing of RSS feeds for a list to be consumed by another system.

The functions are broad, covering many different methods for integrating the capture of content in SharePoint. The most important thing to understand is the necessity and governance of such integrations and how it relates to the other forms of capture. For example, surfacing documents that live in another content system impacts the way an organization will plan their ECM environment and train their users.

After content is captured, it has to be properly stored. This moves us to the Store process.

Store

Storage is not just the writing of a document’s content to a list or library. It also refers to all aspects of that document, including its security, its history, and its metadata. The following pieces of document storage are listed in the order that they should be implemented and used:

Storage is the physical and logical storage of content and associated metadata. The distinction is important. Some might consider storage as equivalent to file shares and databases. The danger in this is that in ECM we add a strong logical component to storage in the form of metadata. It’s this metadata that makes downstream ECM processes possible. Without it, you end up neglecting information architecture in favor of a new representation of the old shared drive paradigm or forgetting that the physical file has to be saved somewhere as well. This results both in no planning for scalability and in hitting a wall at some content storage limit.

In SharePoint, the physical storage happens in Microsoft SQL databases. These databases are referred to as content databases. This is the physical location of the BLOB object that makes up the documents content. Metadata is stored in a separate location and then linked to the content BLOB.

Information Architecture is the logical storage of content. This includes web applications, site collections, sites, list, libraries, and content types. This includes their configuration, number, and relationship to each other.

Arguably, information architecture is one of the most critical components to successful ECM and is where an organization will spend the majority of its time planning.

SharePoint also supports configuration of Remote BLOB (Binary Large Objects) Storage (RBS). We will talk more about this in Chapter 2.

RBS can facilitate a measure of scalability for specific use-cases that involve large individual file sizes and/or high volumes of objects. The configuration of RBS can be targeted to specific SharePoint Web Apps, Site Collections, or individual sites.

An example of this would be large engineering vector files and high-volume document imaging solutions. In most use-cases, RBS is not necessary, and storing the objects in the database has the advantage of providing one source from a backup and disaster recovery perspective.

To continue the theme of making sure that your ECM team is speaking the same language, let’s look at the specific aspects of a standard SharePoint information architecture so that we are all on the same page.

Information Architecture

Often, Information Architecture is confused with one of its individual components, such as folders or site collections, rather than looking at it holistically. We find that while many organizations implement Information Architecture organically, very few know what it is. We can visualize all aspects of Information Architecture in Figure 1-3, showing that this is the logical location of content in SharePoint. The figure shows, in a hierarchical order, all aspects that define the logical storage of a document and how its metadata is represented. In later chapters, we will define each of these and their use in detail.

The growing trend is to make the repository portion of Information Architecture as flat as possible and the metadata portion as comprehensive as possible. Later in the book, we will talk about the theoretically ideal Information Architecture and align it with practical implementations of SharePoint. We will come up with guidelines for designing your Information Architecture.

Note

What you might not realize is that a folder is just a piece of metadata. To file systems, a folder appears as an extension of the file name. What folders do is offer a single point of view for content, which is too limited because it doesn’t provide flexibility in terms of user search. Additionally, in situations that require support for large volumes of content, folders have inherent rendering limitations. By incorporating a flatter information architecture with more metadata, users can slice and dice content according to several variables at the same time, changing that single one-dimensional point of view into a multidimensional, flexible way to browse and search for content.

We dare to suggest that Information Architecture is not only the place where you will spend most of your time in planning a good ECM solution, but also a place where you can have fun. For those who strive to be organized, Information Architecture is where it happens.

In contrast, the use of proper metadata in content types instead of folders allows a user to slice and dice content on any number of combinations of information they want. Metadata provides a more flexible means of organizing and reorganizing content on the fly. Surfacing content in visual folder layouts is acceptable, but it must be used in conjunction with metadata and search.

Versioning

As documents come in to the right location, in the right format, they often need to be versioned.

Versioning is the process of storing earlier versions of a document with their associated time and date stamps. The earlier versions might be used to revert back to previous version, for comparison across versions and for sharing one version while a more current version is still being edited. This is not to be confused with tracking changes in a Word document; tracking changes is a function that facilitates the creation of versions, but it is not a version control system. In SharePoint, versioning can happen automatically. When a document is saved, it is possible to save a major version or a minor version. The versioning number system is what determines whether it’s major or minor. A minor version is everything to the right of the dot or decimal, and the major version is everything on the left side. For example, a document with version 3.5 has a major version of 3 and a minor version of 5.

Because major and minor versioning is usually used only when an organization publishes documents—for example, to an extranet or partner portal—the major version represents the published version while minor versions remain unpublished and continually edited. So while editors are working on version 3.5 and on to 4, the people who have access only to published versions see version 3. When versions are saved, the editor has the ability to add comments to help identify what changed in the version. Some versioning happens upon document upload and is automatic, based on filenames that already exist.

There are two dangers of versioning. The first is blindly enabled versioning, which could result in the overwriting of files without the users knowing. The second and more serious danger of versioning is the impact it has on content databases by adding a separate copy of the document and additional comment metadata. This can cause a site collection to get too large too fast.

One of the huge benefits of the SharePoint Platform is that anything and everything can be content. Besides file size limitations per file, there is no limitation on the type of file you can upload to SharePoint. However, there are best practices for choosing which file formats to support as a policy. The considerations are based on how functional the files are, how they can be viewed or edited, and whether they pose any security risks.

The most common formats used are MS Office documents and PDF files. But it’s not uncommon to see media files, CAD files, and other proprietary file formats. Another part of file formats in SharePoint is a mechanism called iFilter. The iFilter is what makes content useful to SharePoint. It exposes the internal content of the document in a way that SharePoint can index and search on it. It also is necessary for third-party products that run within SharePoint to visualize, edit, or otherwise work on the content.

Transformation

As we indicated in the From the field sidebar on formatting, transformation, while not always a consideration, often becomes an important consideration when it comes to the types of file formats you allow and the desired formats to have in the ECM system.

Transformation, also referred to as conversion, is the process of taking an original file format and converting or transforming it into another. The transformation process often is just a format change, but it can also include other processes, such as optical character recognition, natural language processing, translation, and other types of content manipulation that make the resulting document more useful. SharePoint has some built-in conversion functionality for Office documents and hooks to incorporate other transformation processes.

You now have the documents captured, properly stored in a content database in the right filing location according to your Information Architecture. You have them in the right format with versioning capabilities. Guess what? This is starting to look like a real ECM system. Now let’s work on managing the content that has found its way into SharePoint.

Manage

The Manage portion of Enterprise Content Management comprises all aspects around governance of the system. This includes informal and formal policies for users, the requirements for how content is captured, the requirements for how content is stored and secured, what is involved in records management, how and when content is deleted or consumed, and finally, but most ignored, how the system grows.

Governance is defined as bringing together all the elements necessary to facilitate the long-term preservation, accessibility, and disposition of content. This is first accomplished by establishing Organizational Policies and Procedures and often includes authoring and review of a document reviewed and approved by the Legal Department and then formally adopted by the Board of Directors. After this is completed, it can be used as a guideline for implementing a records management plan that includes a formal definition of records, how long they are to be kept, how they are disposed of, who has the authority, and what to do in case of litigation. In conjunction with well-defined Information Architecture, a complete governance plan can help ensure that the user adoption is high and that the extensibility of the ECM solution is straightforward

Governance includes the following elements:

Records management

Records management, like its broader parent, ECM, is a practice and methodology. However, records management requires a far more strict set of principles. Records management includes the following disciplines:

A record is a stamp in content, time, location, and metadata for a document. When a document is declared as a record, its content will not change; the metadata, such as last modified data, will not change; and its logical and physical storage location will not change. Very often, there is an additional step that occurs during records declaration, which is a reassignment of security so that individuals who don’t have authority cannot access the records.

In the past, SharePoint records management was limited only to record centers. A records center automatically declares all documents as records when they are saved in that site collection designated as a records center. However, now with SharePoint 2013, records declaration can happen in a records center or in any other library automatically, via a workflow, or with manual in-place records management.

Records and non-records alike might be subject to retention schedules. A retention schedule is a listing of all document types and their associated life spans. For example, a contract might be deleted five years after the termination date. Retention schedules are required in compliance-driven industries but are not common in smaller business. However, the use of retention schedules is an excellent discipline for any organization and can be a cheat sheet for implementing ECM in SharePoint.

Records management, even when implemented, does not apply to all content. The relevant content is determined by the retention schedule and is usually critical to business operation or contains potential risk/value associated with compliance or litigation. Organizations, even without records managers or records management policies, can choose to learn from the strict organization principles so that the can be better prepared for future compliance restrictions or litigation. The retention schedule also determines which elements of metadata are required or not. This particular practice of deciding what metadata is required or not, while mentioned here in records management, is mandatory for all organizations.

Note

Sometimes the enforcement of mandatory metadata is referred to as “management by the red asterisk” because of the symbol placed next to mandatory metadata fields. The plus of this strategy is that you get better metadata when content is added; the minus is that users add less content to avoid it. There is a balance to be achieved.

In your organization, it’s not the content you know about that can hurt you; it’s the content that you don’t know about.

Security and access

Another huge benefit to SharePoint is its ability to manage security at nearly any level. What you learned above about Information Architecture is an absolutely critical element in security considerations. The various site collections, sites, and libraries will all have separate security considerations.

Access levels are among those considerations. Who has access to what? Similar to Information Architecture, the hierarchy of security can spiral out of control. Security and access levels have a direct one-to-one relationship. For example, even though item level security can be achieved in SharePoint, the maintenance and risk of such a policy is high. Also, as with Information Architecture, the trend is to make security envelopes at the top level and flatten and widen the repository where security restrictions are applied. For example, instead of having a site collection for all departments and a site below it per department, organizations are making a site collection per department, with security at the site collection level instead of the site level.

SharePoint has the ability to show to users only content they have access to and also block users out of a repository completely, if necessary. This process is called security trimming and is a tremendous tool that you can use to help protect content and support compliance initiatives.

Security is one way to enforce governance, but it does not solve everything.

Note

Security trimming is the process of showing only the content that the currently logged in user has access to. For example, if you do a search for documents with the term “security” in it, SharePoint will first find all, for example, 100 documents that have the word “security” in it. But because the user logged in has security access to only 20 of those documents, SharePoint will show only the 20 documents the user has access to. This is true in libraries as well.

Policy

There are certain elements to governance that can be implemented with technology, some can be implemented only with rules, and others could be accomplished with either technology or written rule, so a decision must be made. For example, “management by the red asterisks” is the process of making certain metadata fields required for document upload. But this can encourage users not to use the system when over used, so it might be better for an organization to declare to its knowledge workers which metadata is required and which is not.

A policy is a written rule on how to use the system. What is written in a policy is one thing, but how the policy is implemented is far more important. Most policies will also need to have specific procedures and, in some cases, user training to make sure policies are understood. Policy is usually set at an executive, board, or steering committee level. The department management and knowledge workers familiar with the business process generally develop procedures. A policy that is simply published without documented procedures, training, and, ultimately, enforcement is rarely effective. Therefore, part of a policy system must include the enforcement system. What we mean when we say this is that if you are going to make the policy, you have to take action when it’s broken or the policy’s value is nullified.

Organizations might want to believe they can do without policy and utilize technology enforcement or rely on the better judgment of their users. This will ultimately lead to great adoption in the wrong way or to no user adoption at all. Not considering the policy system can result in ECM failure.

Change control

When an organization decides to take on a project like SharePoint, the requirements will slowly evolve with time. They actually start to evolve as soon as the project starts. However, if your organization is similar to others and plans for all adaptations along the way, you will be crippled by planning and ultimately finish nothing. There has to be a system that prepares for changes in requirements, technical environment, and business environment so that these changes do not halt the deployment of a system, prevent its adoption, or prevent its extensibility into future solutions for an organization.

Change control is the process of managing this change. In any system, the life of the system can be impacted heavily by change in organization structure, staff, or even just focus. Change control is the tool used to mitigate these negative impacts on the system so that they don’t accumulate to reduce the life of the system. In ECM, change control starts at the project kickoff and lasts throughout the life of the system on to the next one. It defines the roles, what happens when a change to the system is requested, and who is responsible for the longevity of the system.

By its very definition, ECM is global in scope, so most business systems and processes have an impact on other departments in one way or another. Truly understanding the impact that poor change management can have is usually felt when a system goes down or a process fails. This happens for a variety of reasons, and we have all been there when things go bad due to a random change made without planning, approval, and documentation.

Deliver

The content delivery stage is the process of enhancing content with new information or consuming the content it already has. This includes editing of existing documents, changing of metadata, and sharing of the content with other users. The components of the Deliver stage are as follows:

Search

Editing and viewing

Publishing

Users love the delivery portion of content management. It’s where they start to see the value of capture, storage, and management. The biggest value of content comes when it’s used effectively in a decision-making processes. To do so efficiently, the user interface and functions need to be created to facilitate the rapid viewing and editing of documents.

These tools should be fast and effective. The knowledge worker should burn as little time as possible getting to the desired content and spend the bulk of time reviewing and/or editing the content. The primary tools for delivery are search, editing, viewing, print, publishing, and collaboration.

Search

Search is the processes of using keywords or Boolean logic to locate content and information. The process of search is to issue a query and to review a set of results to determine an appropriate item. While the actual search query feature is fairly basic, the tools that isolate the correct piece of content or, even further, the correct page in the correct content are very complex. Such features include best bets, search refiners, and relevance.

Search can be both a positive and negative indicator. The more often that users find what they are looking for will imply that the Information Architecture is perfect. Also, the fact that you can search across the enterprise is empowering and reduces the time it takes for you to get to content. Therefore, search and Information Architecture are intimately tied and share joint planning. They are so tied, in fact, that they share components. Facets, also referred to as refiners, are components of Information Architecture as well.

The goal of search is to get users to content faster. Search can start out with very basic principles but quickly evolves to topics such as thumbnails, best bets, in-page relevance, and so on. Whatever the cool components of search, the end game is always the same: get the user to the right content with the fewest clicks.

Note

The approach we will stress is to put more energy into Information Architecture and encourage the use of other tools rather than search. But when search is needed, keep it simple until a specific requirement arises.

After a user finds the document, either via search or browsing, they have to be able to view and edit it.

Editing and viewing

While users don’t often realize where they spend their time or why they do what they do, a simple study will prove that users spend most their day in some sort of viewer. A web browser is a viewer, Outlook is a viewer for email clients, and SharePoint is a viewer for content. An amazing amount of time is spent reading and consuming content as compared to creating it. Most job functions spend the majority of their time consuming rather than creating, while other specific audiences, such as technical writers, business analysts, and publishers, spend a lot of time creating and editing. For this reason, the ability to do this seamlessly is critical.

With the exception for records and archived documents, the majority of content is living. It gets edited and viewed on a regular basis. SharePoint has built in viewers for Office documents. This allows you to work with the documents in the manner in which you are accustomed. For other varied file formats, a different type of editor might be required. It’s important in the planning process to understand how content will be consumed, edited, and repurposed.

You need to understand that viewing and editing ties heavily to the formats discussed in the Store stage of ECM. The fewer types of documents, the easier it is for organizations to creating great editing and viewing tools for them. The Office suite has the clear advantage of having essentially bundled viewing and editing capabilities with SharePoint, either with client applications or with Office Web Apps. Documents such as PDF, which is predominantly designed for viewing and not editing, have special considerations when it comes to ease of access. For example, do you allow users to open the PDFs in the browser or client application, or do they have to download to their local machine first?

While the aspects of viewing and editing seem obvious, its considerations are not, which is why it’s an essential component to ECM planning.

Publishing

Publishing, which contains aspects of both search and viewing, is the process of pushing content or allowing content to be pulled, by individuals who are not necessarily the curators, for viewing purposes only.

Publishing incorporates versioning in the storage stage, formatting, and ease of access either by targeted search or great Information Architecture. Usually, publishing also includes portals that are branded with basic themes or other more complex branding to make it a great landing page for content consumption. These portals are called intranets or extranets. Content on intranets and extranets is usually read only and comes from another location within the ECM system. This book will discuss in detail creating and managing content for publishing, or rather, the locations from which content is pushed. It will not cover in detail the configuration and branding of such intranet and extranet portals.

Process

Content is not just viewed on an ad hoc basis, or edited, which is essentially another type of capture. Hopefully, it is incorporated into a decision-making process or line-of-business process. The problem is that these types of processes are usually designated for structured information in SharePoint, such as lists. Documents have an additional element of complexity because their content is unstructured, which means incorporating them into any process requires special consideration about their associated metadata.

Process is taking what has been stored in content and incorporating it into another line-of-business activity. These processes are often unmanned and automatic. However, a manually driven process still falls into this aspect of ECM. The elements of process are as follows:

Workflow

The most common example of process is referred to as approval workflows. This is the process of routing a content item or transaction through a series of predefined steps for approval between different layers of management. This is very common in Human Resources, Finance, and Procurement.

For purposes of this book, workflow describes a process that contains one or more states or steps, incorporates user and system tasks, and is routed in a single direction. The purpose of workflows is to take metadata and content and turn them into action. A SharePoint workflow requires an existing business process to be well understood and defined. In most cases, work just gets done, but the flow of how that is accomplished is not documented or fully understood by all knowledge workers. To facilitate that process from beginning to end, there are user driven activities, management decisions, and transactional exceptions that need to be reviewed and completed. Workflows are very high-value items to automate, but most organizations underestimate the amount of due diligence required to prepare for a workflow automation project.

In ECM, the considerations around workflow are not just the content that is moved around via workflow but the steps and considerations of the content flow itself.

Business Process Management (BPM)

Business Process Management looks very similar to workflow, but it differs in that it allows for multidirectional processes, ability to version processes, and change control for processes. It is said that workflow is available out-of-the-box with SharePoint, but BPM usually comes via third-party solutions. The biggest technical difference is not just the workflows that can be created but also the management of those workflows.

In later chapters, workflow and BPM will be discussed together with the assumption that the user is performing out-of-the-box SharePoint functionality.

Business Intelligence and BigData

After content has been captured and processed, gaining insights from the content is a great way to take their value even further. Business intelligence (BI) is a broad category of technology that extracts greater value from content.

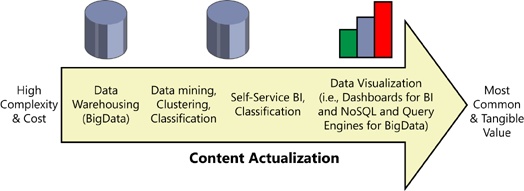

The bridge between BI and BigData is very strong. Therefore, we have lumped them together. Both increase the value of the data and assume some sort of structure and good metadata. Arguably, BI is a subset of BigData, although BigData implies manipulation of large datasets, whereas BI could be big or small. We illustrate this in Figure 1-4 by showing content actualization, starting with the most complex and highest cost and moving toward the most commonly used to achieve tangible business value.

BI really falls into the following three types:

Dashboards and Key Performance Indicators This is most often what people are referring to when they say BI. In SharePoint, this is Performance Point and Conditional Formatting.

User-driven BI This requires some data expertise and is usually performed using Excel and PowerPivot.

Data mining Data mining is the intelligent extraction of value, and in SharePoint, it relies on a third-party tool.

Today, most people refer to BI as the ability to visualize large amounts of data in a graphical way, such as a graph. These are referred to as Dashboards or Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). They are fed by structured content, but unstructured content can be incorporated by using technologies such as Natural Language Processing, Text Analytics, Auto-Classification, or incorporating search into the analysis.

User-driven Business intelligence in SharePoint manifests itself as Excel spreadsheets and, more popularly, the PowerPivot add-in for Excel and SharePoint that allows a user to manipulate data in three dimensions or cubes.

Data mining is the most advanced and expensive use of BI. SharePoint can certainly be a source of information for advanced data mining tools but does not natively have data mining tools.

Arguably, BigData is just another definition of, or a broader definition of, a business system that includes and implies larger data sets and the use of a new database approach called NoSQL. Again, SharePoint does not have native BigData support, but it can certainly be used as a source for BigData third-party tools.

eDiscovery

A very specific type of processing of content is called eDiscovery. This particular process is one that organizations hope to avoid. Not only is the process of audits, litigation, and so on painful to the organization, the cost of such processes when not planned for is phenomenal.

Note

An organization of 250–500 employees with 2–3 TB of data will pay in excess of $300,000 to cover the cost of just eDiscovery associated with litigation. Organizations well prepared for eDiscovery not only reduce the cost when they are faced with a matter; they improve the overall organization of their ECM system. A matter is the subject of legal action, compliance, or content audit. Discovery is the process of gathering content associated with the subject.

When planned for, this cost can be dramatically reduced. And the process of planning for eDiscovery, fortunately, is the same as all aspects discussed in search and Information Architecture. Why? Because eDiscovery is essentially search combined with records management.

eDiscovery seems like some abstract term, but it really talks about an advanced form of search. In a later chapter, we will go into more details about what eDiscovery is, how it’s used, why it’s used, and how it works in SharePoint. eDiscovery is the identification, isolation, and locking of any content that pertains to a matter. The most common instance of a “matter” is litigation. However, a matter could relate to the Freedom of Information Act, content audits, and so on. After eDiscovery is run and content is identified, it must be isolated and separated from content not associated with the matter. The relevant content must be held as a record so that it is not updated or modified, which would make its value null.

It’s safe to say that delivery and process are the areas we all enjoy the most when it comes to consuming content. It’s also the area where the greatest investments and advances in technology are happening. The goal of ECM is to get users to spend more time in the Process stage and less in the Capture, Store, and Preserve stages of ECM.

Preserve

Content, just like everything else, has a shelf life. Most of the time, content that expires is deleted. This is beneficial to organizations from a compliance and legal perspective and as a part of ECM, but there is some content that is long lived. This type of content, when not consumed regularly, just takes up needless space in an ECM system.

Content preservation is about taking that active content generated as part of ECM and moving it to a location in a format that can be accessed, although infrequently, in the foreseeable future. The important aspect of preservation is storage. In this context, storage refers to both the physical storage of the content and the format that the content will be stored in.

Most organizations prefer to use the high-availability content databases for active and vital content only. For archive content, the preference is to see its metadata but not allow the content to take up space in the content databases. This can be done by using tools such as remote blob storage (RBS).

Reformat

It is very common to reformat content when it’s preserved. Ten years ago, the trend was to convert content to microfiche, but today it’s PDF/A. The purpose of reformatting is to ensure that it’s not editable and to ensure that it can be viewed in the future. The reformat process also includes the purging of unnecessary versions and metadata. In addition to reformatting, many organizations also choose to compress their content.

Note

PDF/A is a special PDF format designed for long-time archival of content. It is an open standard that helps ensure the quality of the content and the ability to retrieve the content in any viewer designed to read the format. In addition to the content, it contains standards from metadata.

Reformatting also has the consideration of viewing. How can you be sure that the content you have preserved can be viewed in the future? This is where librarians and content preservationists excel.

Compression

One major consideration for reformatting is the size of files. There is a process of compression that is often considered for reducing the size of files prior to final preservation. The problem is that it’s rare to find compression technology that does not alter the content of a document during the compression process. Lossy content, or content that loses quality each time it is converted and/or compressed, is similar to the result of taking a picture of a picture. Over time, information is lost, and the possibilities for editing, consuming, and repurposing content in the future diminish with each iteration.

Compression is just one type of transformation process that is commonly used in ECM. This process reduces the file size of a document without loss of integrity of the content. With graphics, compression can reduce the quality of graphics, but the content of the documents remains. Compression becomes significantly important when discussing ways to save space and archival processes.

Overall, preservation is not all too common, and as the cost of storage reduces and technology for managing content improves, it becomes less and less common. For that reason, preservation will be referred to in this book as a possible end to a document’s life in SharePoint, using such tools as RBS and SendTo locations.

Why use ECM?

Now that we have covered all the aspects of ECM, let’s talk about the “why” and “who.” Specifically, why should your company, department, or team implement ECM? Who will be responsible for implementing ECM, and who will use and benefit from it? The remainder of the book will then cover the “how.”

Do not mistake the question of why you should pursue ECM with anything your organization has in terms of current SharePoint implementation. Our goal for “why” you will implement ECM is a question that assumes the perfect hypothetical ECM system, a system where a knowledge worker’s effort to capture and categorize content is minimal but the amount of metadata capture is high, and the cost of finding and consuming the content is very low.

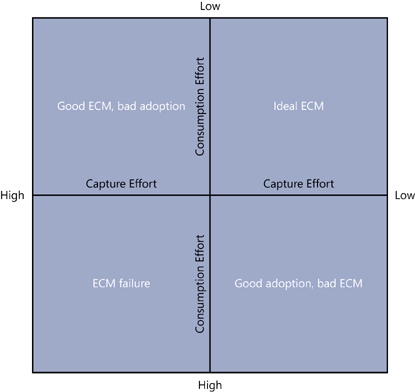

These goals are often at odds with each other. For example, expecting a user to enter content into SharePoint in the perfect way means that at time of capture they have to put in additional effort. By not getting the content captured in an ideal manner, the findability of content suffers from long search times and getting, at best, duplicate content and, at worst, the wrong content. In Figure 1-5, we show the contrast in effort between getting content into SharePoint (Capture) and retrieving or finding content (Consumption). Ultimately, you want to automate the process of capturing content to provide enough structured and validated metadata to make the consumption of the content relatively easy.

Note

Findability is a measure of the effort it takes to locate a document. Content with greater findability enables a user who intends to locate a document to do so with the least amount of effort. Findability can happen at the platform level with tools that improve the quality of all searches, and at the content level with better metadata. You will sometimes hear the term putability, which, similar to the term findability, is the measure of how easy it is for a user to contribute high-quality, easily findable documents inside of SharePoint.

It was said earlier that it is possible for organizations to plan forever. So it’s important to note that all aspects of ECM come with a balance. The emphasis is unique to each organization and its current environment. While it’s frustrating, it’s a fact of ECM life, and it needs to be accepted.

Therefore, for the sake of this section, we will assume that the ideal ECM solution exists. Your organization’s motivating factors for implementing ECM will come from two primary drivers: reactive or proactive.

Proactive driver

It’s rare for knowledge workers without the skill set of content management to be interested in ECM without a reactive driver. However, you might have departments or managers that promote a culture that values organization. And from the perspective of being organized, they embrace the methodologies of ECM. Ironically, it’s also these departments and this culture that resist change, because they very often have a well-established system for filling content and are not much interested in taking that away.

Another area where organizations are proactive is when ECM has a direct impact on operational costs. This is most often where content touches a line-of-business application. This can be found in health care, insurance, accounting and finance, banking, and so on—that is, organizations where everything has a process and there is content involved. The benefit of these organizations is that they usually already have a retention schedule and content that varies very little in topic, so building an ECM solution is very simple.

And finally, there are the select few, like the book’s authors, who love the idea of getting content under control so that greater value can be attained. It is our goal that some readers of this book will finish in this category. Now let’s talk about those reactive drivers which are a more common catalyst for ECM.

Reactive driver

Reactive organizations have faced some negative event where the cost of poor ECM was evident. The most common such events are litigation and compliance, where a company was the defendant or claimant in a lawsuit. I’m sure that you can spot something in your organization where you can’t help but laugh at the way things are done. At some point, these areas of operation, you hope, are addressed with new approaches.

The second most common is compliance driven. A good example is if your organization operates in an industry that is compliance-heavy, like health care, insurance, or banking. These industries deal with a tremendous amount of regulatory burden. In fact, many of the legislative actions taken to create regulations like SOX (Sarbanes-Oxley), HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), and Dodd–Frank (Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act) contain very specific provisions that can be complied with by using components of an ECM solution.

The benefit of the later reactive scenario is that very often, in such cases, the implementation of ECM is very clearly defined, and it’s more a matter of conformity. Most often, these organizations, due to their history in the industry, already have a good sense of what needs to be done, and their business challenge is adoption rather than implementation.

For the reactive scenario in litigation, these organizations very often were not aware of what was wrong until it hit them. The process of getting content associated with this litigation is called eDiscovery. Later in this book, we talk in more detail about eDiscovery. The cost associated with eDiscovery is phenomenal. Therefore, to be better prepared and to mitigate these costs in the future, organizations are deploying proper ECM solutions and participating in what is called early discovery.

The reactive scenario is not what the world of ECM hopes companies are using as their primary driver for implementing ECM. The hope is that organizations are thinking about what it takes to best actualize content, get the most value from content, and to make their knowledge workers as effective as they can.

This scenario is very rare and usually combined with one of the above reactive scenarios. There are a handful of organizations who believe that if they better capture, store, and deliver content, their costs of working with content will be reduced, the effectiveness of their staff increased, and finally, that they can move that content into more valuable decision-making processes, such as workflow and BigData.

How can you use information to make better decisions?

Information is just bits of data; it’s stored everywhere, and access to the information is abundant. Putting information in context provides the ability to acquire knowledge. Knowing when and where to use the knowledge gained from the information is wisdom. Putting wisdom into action is what differentiates individual performance and enables streamlined decision-making. As shown in Figure 1-6, each step represents a greater degree of meaning derived from content. Departments, workgroups, and knowledge workers who can harness the Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom steps will help an organization to perform at a high level.

Businesses generally make the mistake of thinking they are managing information by having hardware, software, and communications. In the majority of organizations, information is stuck in silos, duplicated without control and communicated in an inconsistent manner. A well-architected ECM solution can enable the enterprise to overcome the chaos and achieve remarkable results.

It is important to understand the difference between structured and unstructured content.

Structured content A simple example is the color of red. This can be seen as a keyword value pair and can be used to create lists, tables, and relational context. This type of content is easy to get value from but is harder to create.

Unstructured content This book is an example of unstructured content. This type of content amounts to 80 percent of all content and is easy to create.

The justification for ECM is to help knowledge workers create structure out of unstructured content. This helps them become more efficient by empowering them with content in the right context at the exact moment they need it. In today’s world, the volume of information is exploding at an exponential rate. Knowledge workers at every level of the enterprise are adopting a myriad of devices and technologies. Enterprises understand the value of information; we can all agree that the right information can mean the difference between success and failure. The only way the enterprise can get to the stated benefits of BigData, business intelligence, process efficiency, and business automation is to design, implement, and manage an ECM solution that focuses on helping knowledge workers access information successfully.

What is a flexible content structure? This is the ability for anyone to create, name, and store content without policies or requirements for organizing content in a meaningful way. This is what enterprise and knowledge workers have been allowed to do since the rise of the personal computer.

As long as the flexible content structure world exists, you need ECM. Most people think that because they are creating content they are managing it. This is blatantly false, and the end result is nothing short of chaos. Users have no idea where to find content; they spend most of the time searching and sifting through irrelevant and duplicative bits of information that was never stored with any thought of how to find the information later.

Return on investment

The primary drivers that create a positive economic impact on the enterprise are revenue growth and profitability. A secondary driver, like increased productivity, is more difficult to measure but nevertheless creates a substantial return on the investment for a well-structured ECM platform. We know that knowledge workers spend 5 to 15 percent of their time reading information, but up to 50 percent looking for it. The ability for a user to quickly find the information they are looking for is important. Even more important is finding that information in context of the business activities or systems that they already use.

To achieve even larger productivity gains, you have to move beyond just finding information and toward automating the collection, distribution, and processing of the information. ECM platforms provide a distinct advantage for business process improvement by automating common processes and reducing or eliminating redundant activities. Process re-engineering is a fundamental part of implementing a successful ECM platform. This goes beyond the technology and requires a commitment to change management and feedback loops to help determine where inefficiencies exist. Some of the changes will be procedural in nature and might require changes in human behavior, which is always more difficult than configuring the technology.

The duplication of content is pervasive. In a world where storage is cheap and nearly everything has a synchronization option, it’s important to think beyond just ease of access. At some point, the original content has to be discarded as it reaches the end of its life cycle. Your ability to ensure that content that needs to be deleted is actually deleted can provide the enterprise with cost avoidance by reducing the risk of having discoverable content in the eventual case of litigation.

Who does ECM target?

ECM targets different people for a variety of reasons and use cases. ECM is a set of disciplines that are used to guide the development of Information Architecture and governance.

A successful ECM platform supports the management of information for operational, transactional, and regulatory purposes. It provides access to the unstructured information assets that complete the record of a transaction, project, person, or activity. The information stored in an ECM platform is supportive in nature to all other systems used in the enterprise, putting structure around this information to control how it is used, who has access to it, and what processes are enabled to leverage it. As a document nears the end of its life cycle, the ECM platform is used to discard information to achieve compliance and reduce risk.

Everyone in the organization benefits from ECM. The key players that are targeted are broken down into those who implement and manage the SharePoint platform and those who access the information stored in SharePoint. Table 1-1 describes how to segment the roles and responsibilities of each of the individuals targeted.

Building expectations

SharePoint offers an amazing set of tools and functions that can be used to deploy a myriad of business solutions. To focus and give you tools that you can use from day one, we are providing an Information Architecture section. In this section, we will discuss the standard building blocks of a SharePoint ECM solution, namely Site Collections, Document Libraries, Content Types, and the Records Center. When you understand what these terms mean and how they work together, you can incorporate the control that every organization wants and needs. Governance can too often be unbalanced, creating either a system that is clunky and difficult to use or one that is too open and ends up being a digital landfill. This is where a well-defined taxonomy that is neither vague, overly granular, nor verbose will help everyone follow the same rules. We will look at types, best practices, and a real use case of taxonomy in action using the Term Store.

SharePoint 2013 is a very powerful on-premise server based solution that is also available as an off-premise Cloud solution. Primarily targeted at small and medium sized organizations, Office 365 takes minutes to sign up for but in the range of a few hours to be fully configured. Administrators will have immediate access to settings for provisioned services. The core Services, Lync and Exchange, are available in minutes, but initial configuration of a multitenant SharePoint site takes around two hours to complete. We will discuss the ins and outs of the configuration options and introduce the concept of the Office Store.

All versions of SharePoint have benefited from a large, talented, and enthusiastic partner community. SharePoint 2013 continues to provide great opportunities for Microsoft Business Partners and Independent Software Vendors to build complementary technologies and vertical solutions that extend the platform. We will outline some vendors and applications that you should evaluate during your project planning and requirements definition. Knowing what technologies are available and how they can help to make your SharePoint ECM solution better will be a real advantage.

The legal and regulatory aspects of ECM from FOIA to SOX can seem like an overwhelming bag of acronyms. To help you navigate what is relevant and what is not, we will introduce the most common laws and practices that you should consider and how to address them in SharePoint. Litigation is a pervasive part of the business landscape, and being able to support eDiscovery requirements in the event of a lawsuit is critical. We will cover the technical aspects of SharePoint that are necessary for performing legal holds, controlling full fidelity of content, and supporting chain of custody.

Next steps

We have covered the difference between SharePoint as a technology platform and ECM as a methodology. In Chapter 2, we will dig deeper into the ECM Stack and uncover in detail the complexities of each stage of the content life cycle. The sections will follow the same structure but include actionable steps you can take to get comfortable planning for ECM in SharePoint. As you’re reading through each section, you should be gathering pertinent information about your specific environment and creating a high-level roadmap for implementation.

At this point, you should begin identifying the stakeholders for the ECM solution you will be designing. You need to separate the functions of SharePoint from the information architecture that your organization will use going forward. Identify your existing content repositories both inside and outside of SharePoint, and determine where they meet or fall short of the principles we have outlined in this chapter.