chapter one

The relationship between Emotional Intelligence and job performance

An evidence-based literature review with implications for scientists and engineers

Mark L. Lengnick-Hall

University of Texas at San Antonio

Christopher B. Stone

Wichita State University

Contents

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI)—also known as emotional competence—has been a focus of research interest for several decades. At its most general description, EI has been defined as the “ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions” (Salovey & Mayer, 1990, p. 189). Joseph and Newman (2010) report that EI has stimulated interest among human resource practitioners who have embraced the concept and used it in personnel hiring and training. They provide evidence of this interest by identifying 57 consulting firms dedicated primarily to EI, 90 organisations that specialise in training or assessment of EI, 30 EI certification programmes, and 5 EI “universities”—and this was in 2008. We can only imagine how this EI “industry” has grown since then.

There continues to be debate among those who consider EI a major organisational tool versus those who question its utility and scientific foundation. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an evidence-based review of existing high-quality research and scientific knowledge regarding the relationship between EI and job performance. Additionally, we provide implications for the role of EI in the job performance of scientists and engineers.

We follow the principles of evidence-based management practice as outlined by Barends, Rousseau, and Briner (2017): (1) translating a practical issue into an answerable question, (2) systematically searching for and retrieving evidence, (3) critically judging the evidence, (4) pulling together the evidence, (5) incorporating the evidence into the decision-making process, and then (6) evaluating the outcome of the decision taken. Our focus in this chapter is on steps (1)—(4). We leave steps (5) and (6) to decision-makers in organisations.

In this chapter, we ask specific questions about the relationship between EI and job performance, systematically search for and retrieve a particularly high-quality source of evidence (published and peer-reviewed articles), and critically examine the quality and implications of the findings. We also examine and assess the pattern and extent of such evidence.

Emotional intelligence

Part of the controversy regarding EI hinges on construct clarity. Two alternative approaches have been taken in defining EI. In one approach—the ability-based approach—EI is viewed as a type of intelligence or aptitude that overlaps logically with cognitive ability. This is the approach taken by Salovey and Mayer (1990) who define EI as a set of abilities that includes four branches or dimensions, including (1) accurately perceiving emotions in one’s self and others (emotional perception); (2) using emotions to facilitate thinking (emotional facilitation); (3) understanding emotions, emotional language, and the signals conveyed by emotions (emotional understanding); and (4) managing emotions so as to attain specific goals (emotional regulation). In contrast, mixed EI models view EI as a combination of intellect and various measures of personality and affect (Joseph and Newman, 2010). To further complicate the issue, many believe ability-based EI to not only have a stronger theoretical foundation but also be a weaker predictor of job performance, whereas mixed EI is believed to have a weaker theoretical foundation but is believed to be a stronger predictor of job performance.

In this chapter, we seek answers to the following questions:

Is there a relationship between EI and job performance? If so, how strong is it?

Does EI incrementally predict job performance when measures of personality and cognitive intelligence are included as predictors?

What mediates the relationship between EI and job performance?

What moderates the relationship between EI and job performance?

Methodology

We searched three major multidisciplinary databases: (1) ABI/INFORM Collection, (2) Business Source Complete, and (3) PsycINFO. ABI/INFORM Collection provides access to three electronic resources which can be searched simultaneously: (1) ABI/INFORM Dateline, (2) ABI/INFORM Global, and (3) ABI/INFORM Trade & Industry. ABI/INFORM Global indexes and abstracts over 1,800 business periodicals. ABI/INFORM Trade & Industry offers more than 750 specific trade and industry publications, while ABI/INFORM Dateline provides access to 170 local, city, state, and regional business publications. Business Source Complete provides full-text coverage for over 9,400 general and scholarly business journals and other sources in marketing, management, economics, finance, accounting, and international business. PsycINFO covers professional and academic literature in psychology and related disciplines, including medicine, psychiatry, sociology, education, and linguistics. It indexes and abstracts articles in more than 1,900 journals worldwide.

Our procedure across these databases involved searching for article titles and abstracts for the terms “emotional intelligence” OR “emotional competence” AND “job performance” or “work performance.” Our goal was to narrow our results only to articles examining the relationship between EI and job performance. We searched exclusively for articles in which our key search terms (emotional intelligence, emotional competence, job performance, and work performance) were included in the title or the abstract to ensure that we only identified articles that were specifically about our topic of interest and excluded articles which did not examine the relationship between EI and job performance.

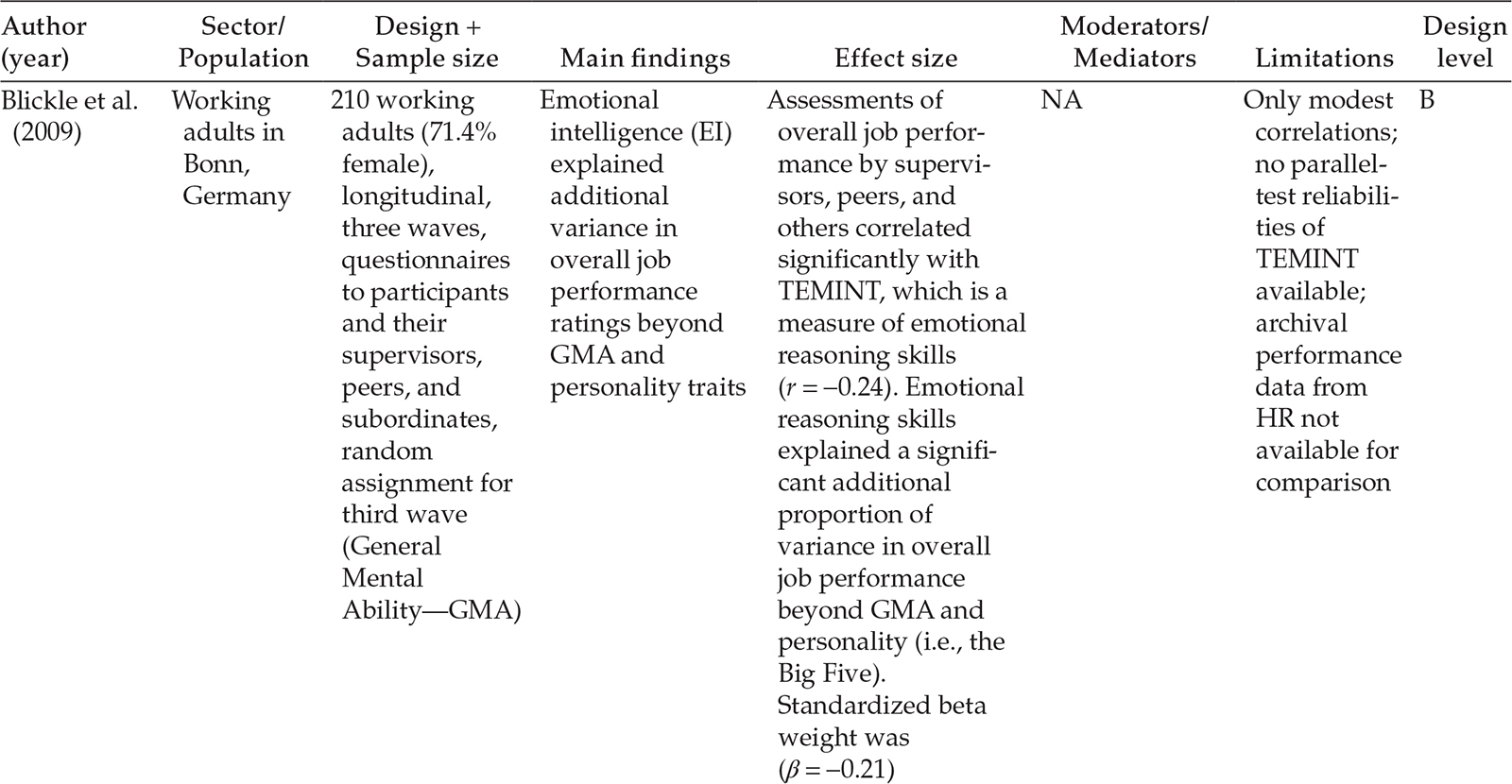

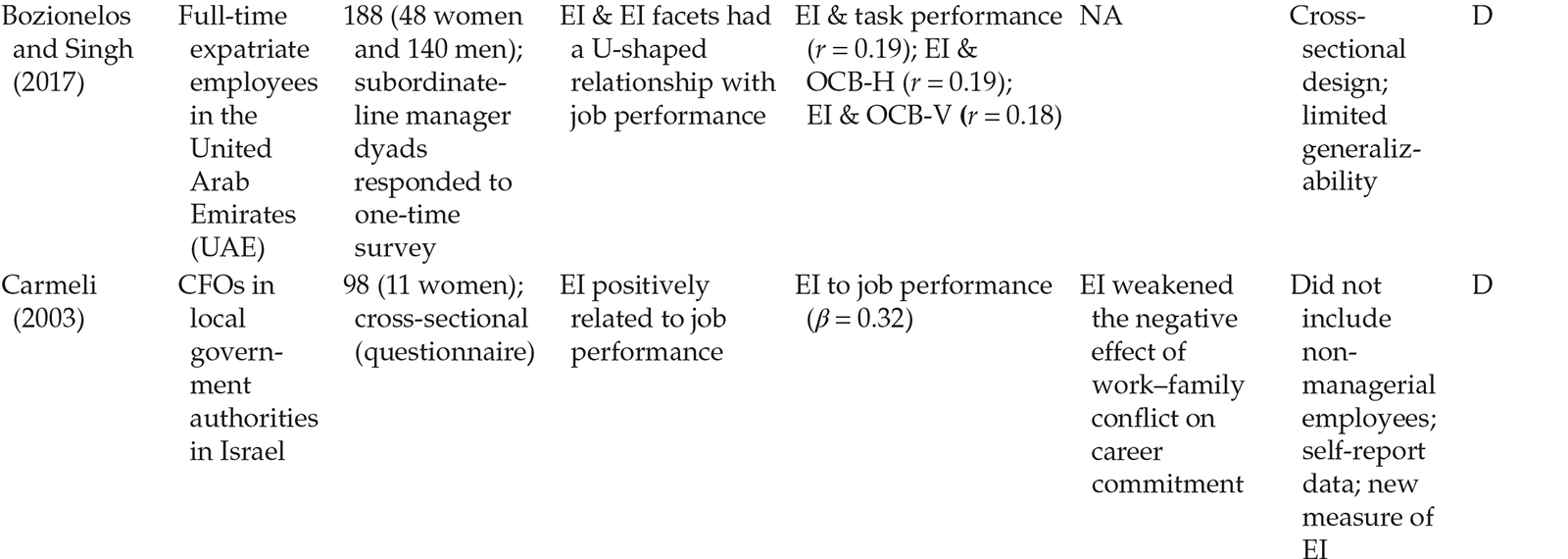

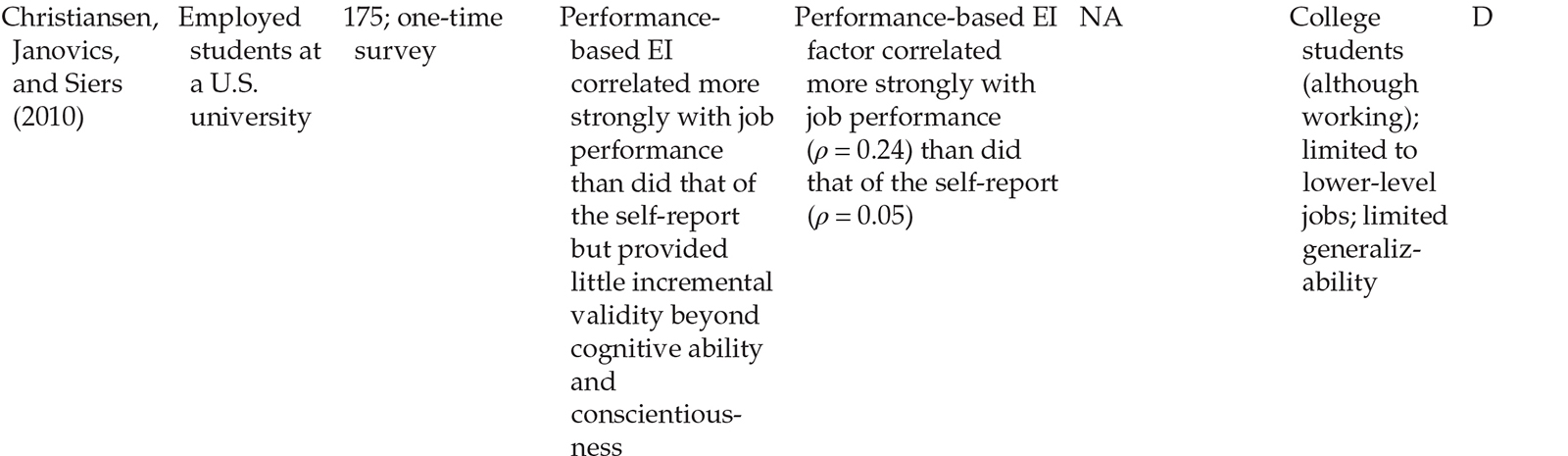

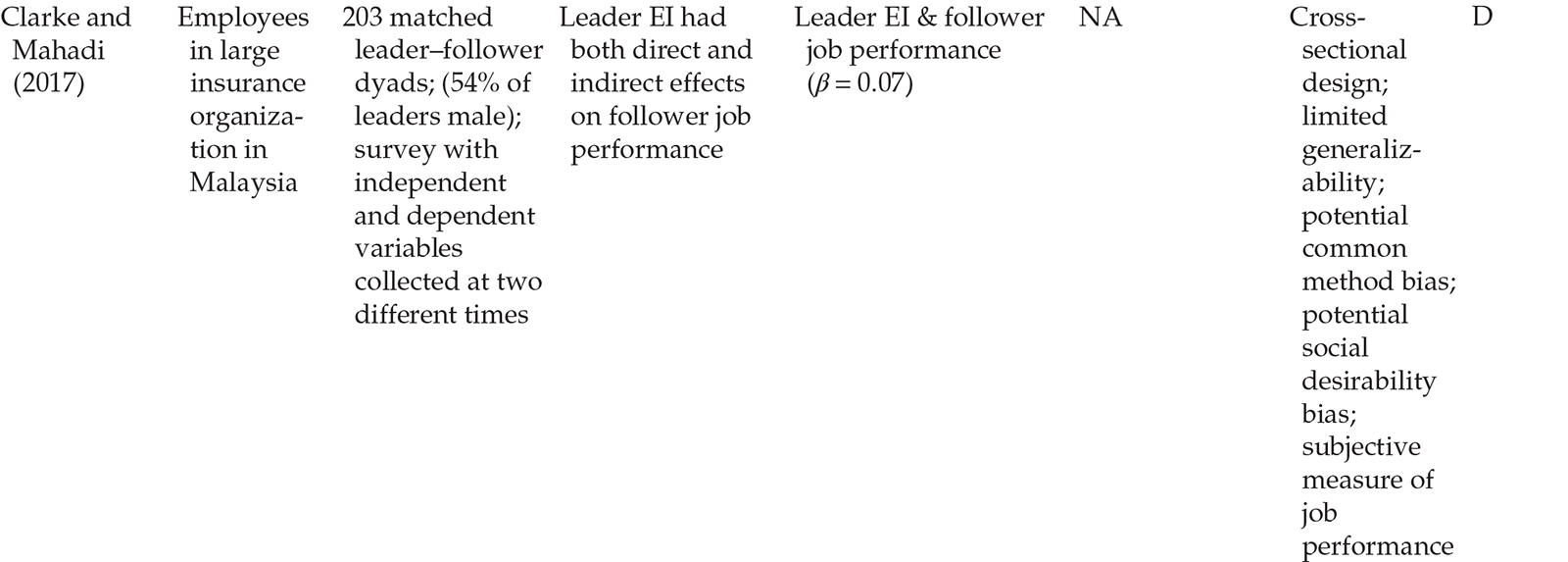

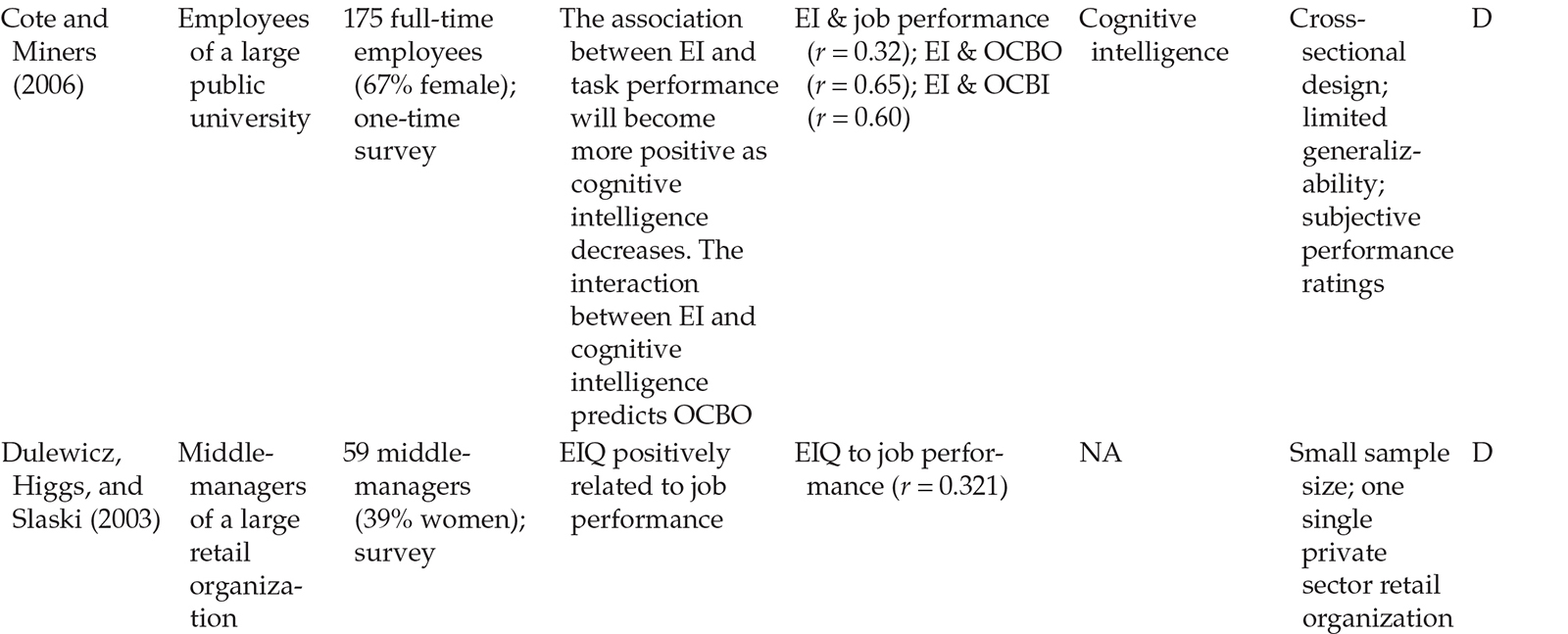

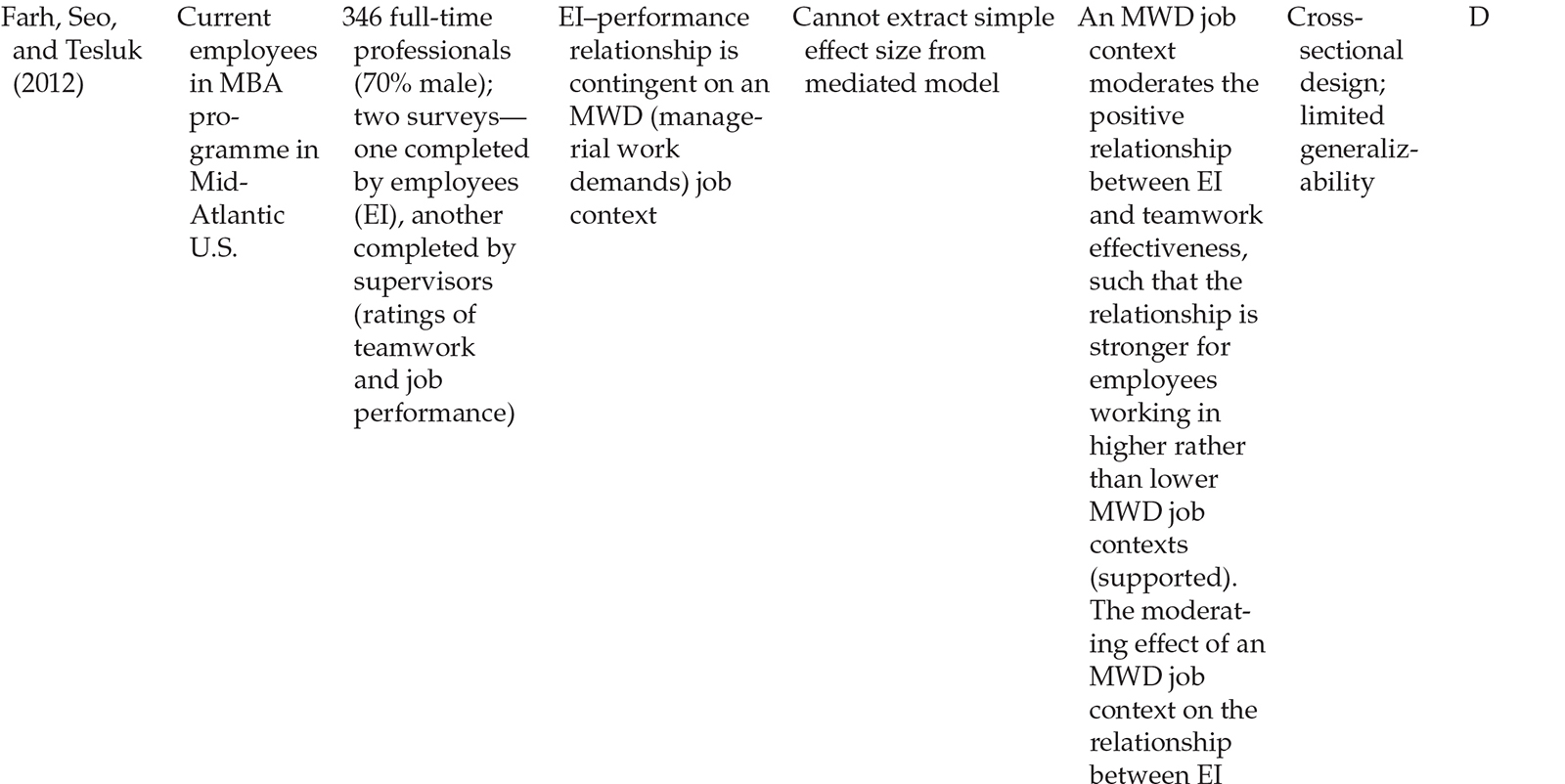

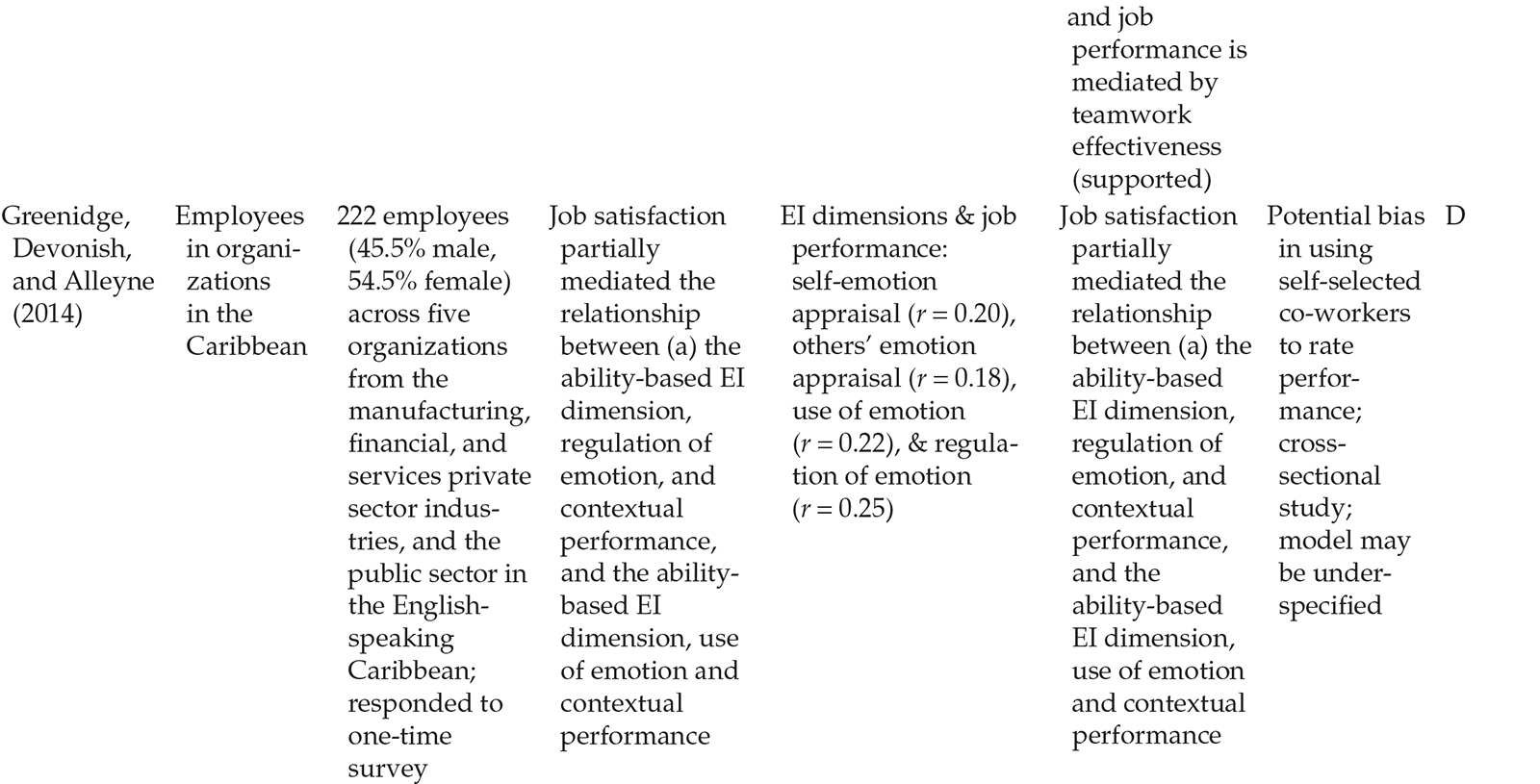

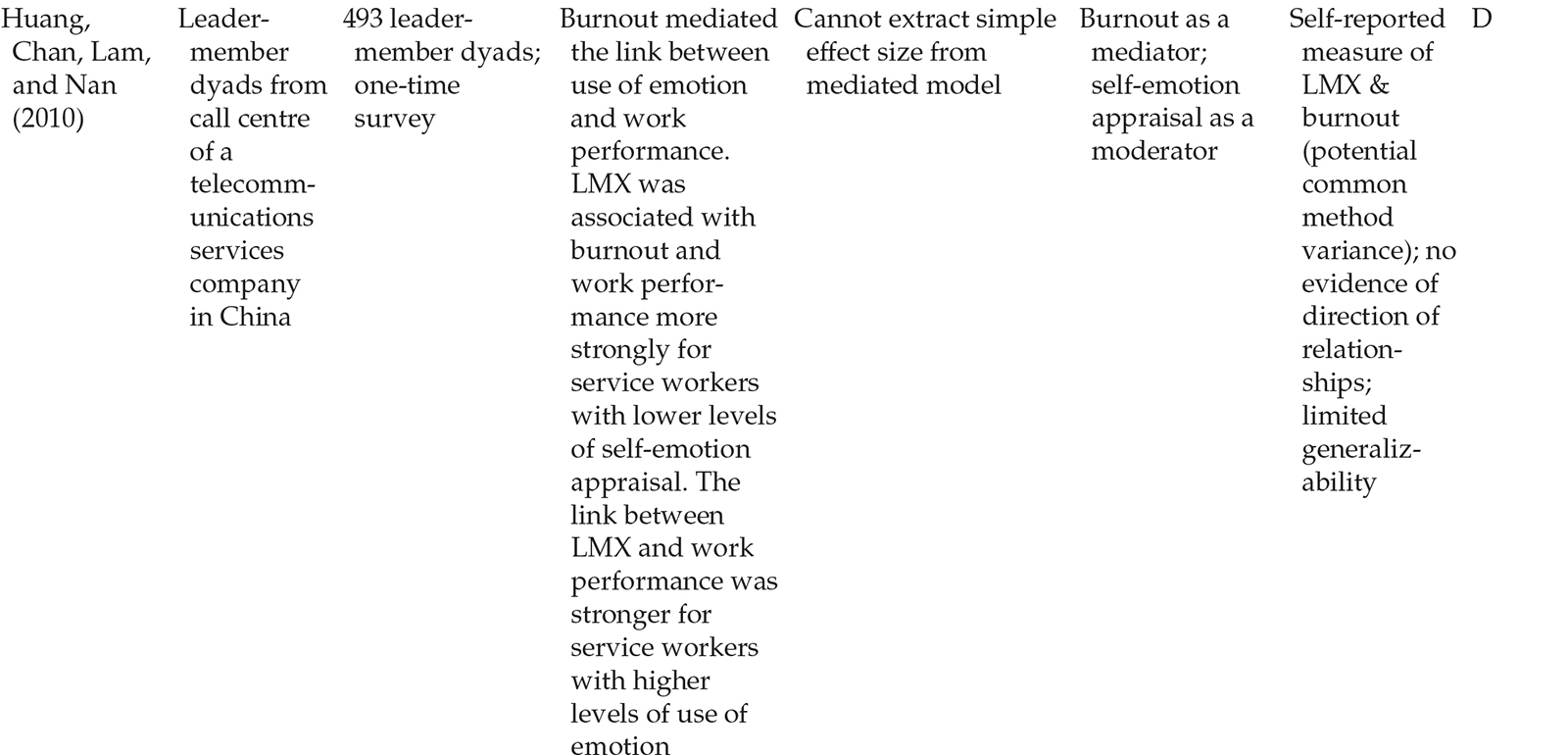

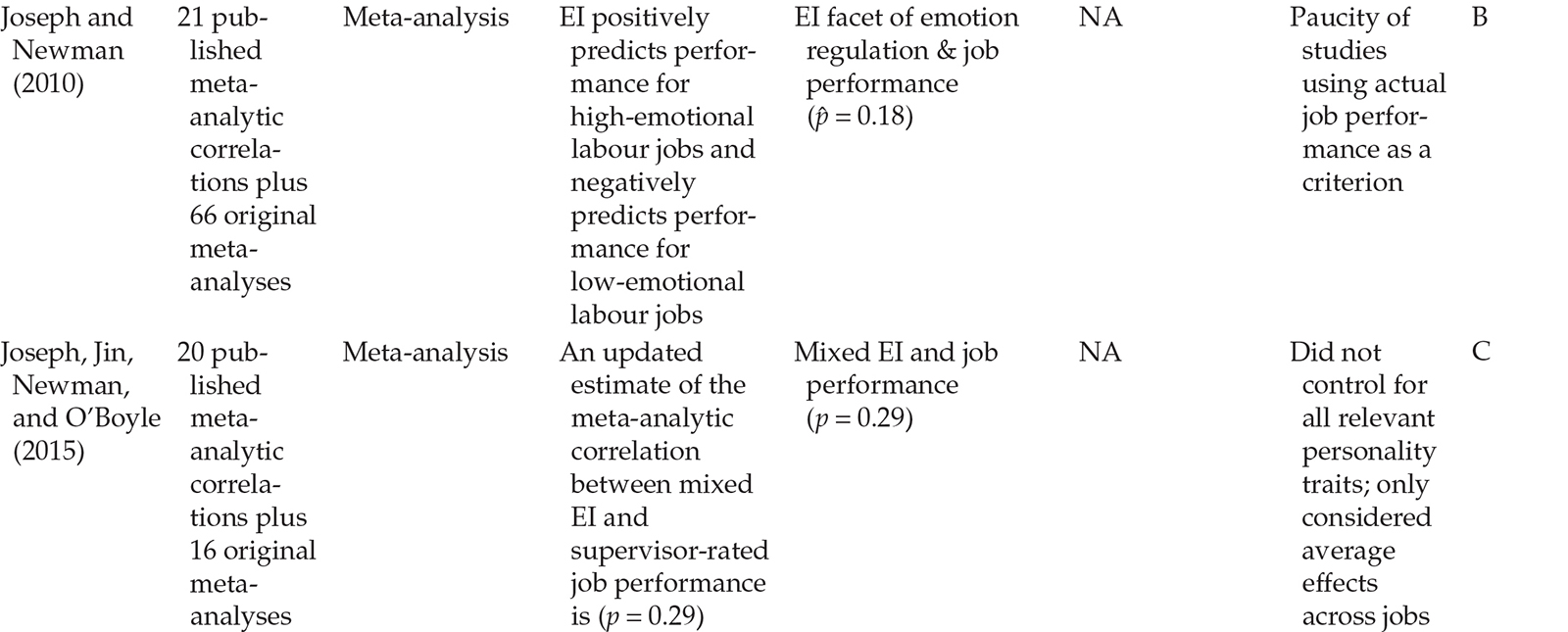

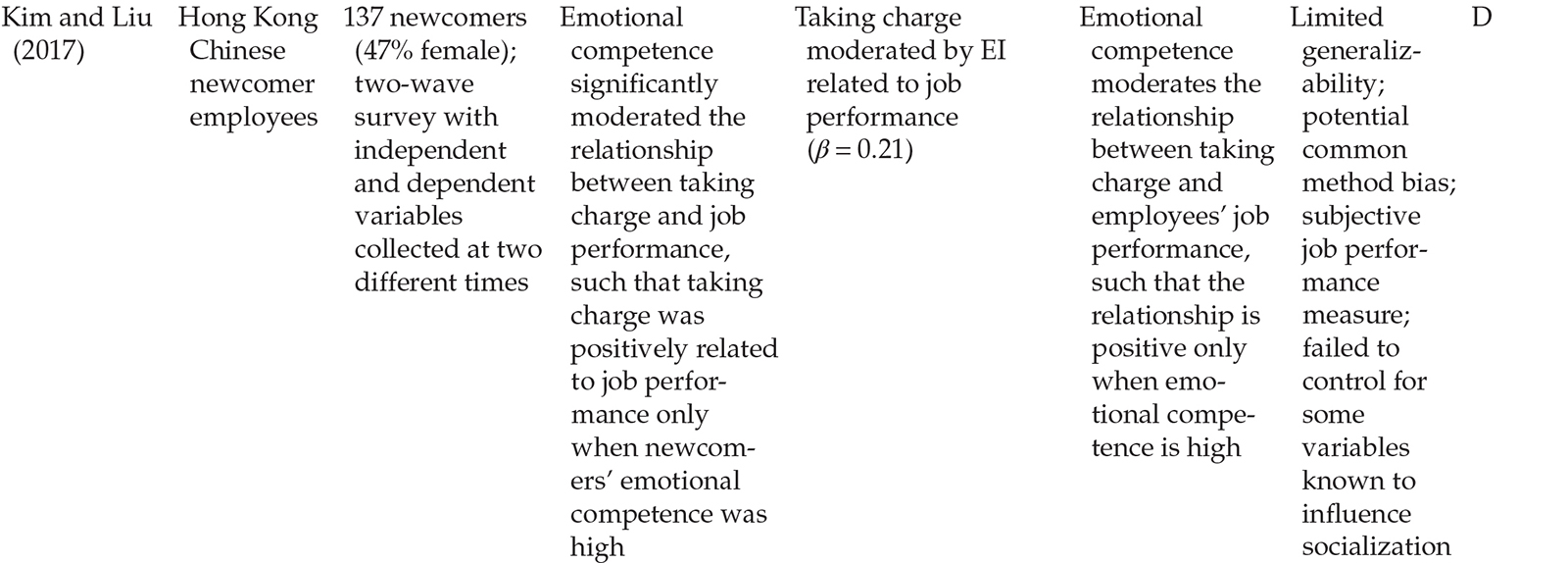

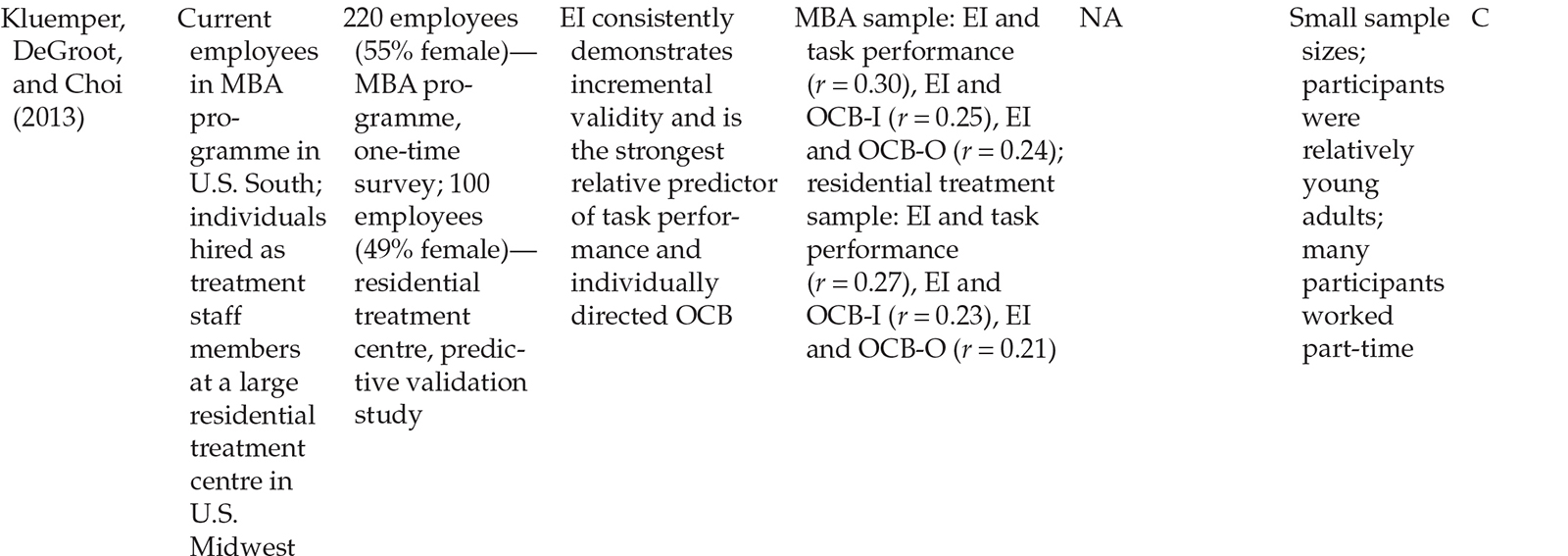

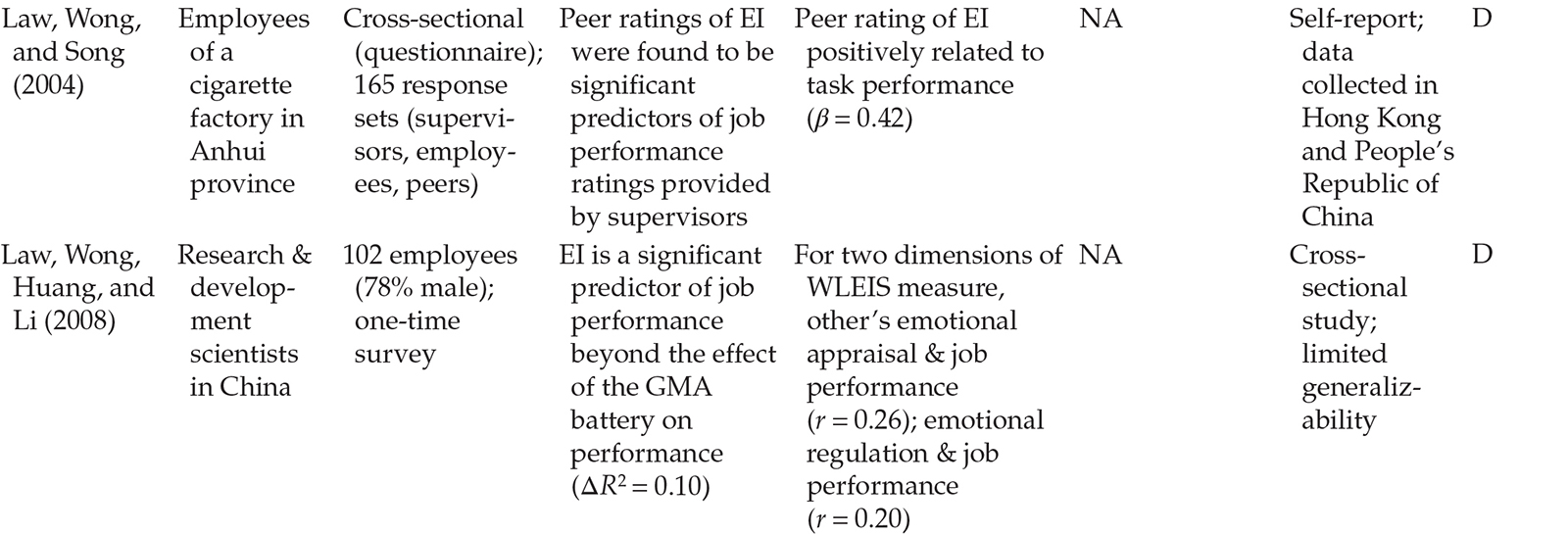

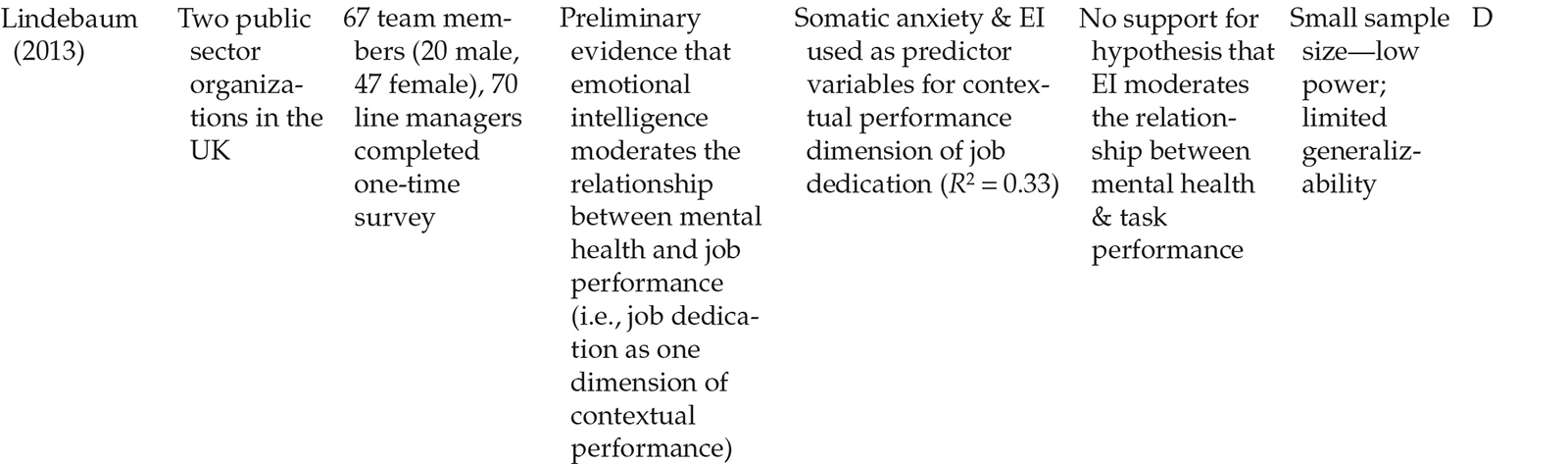

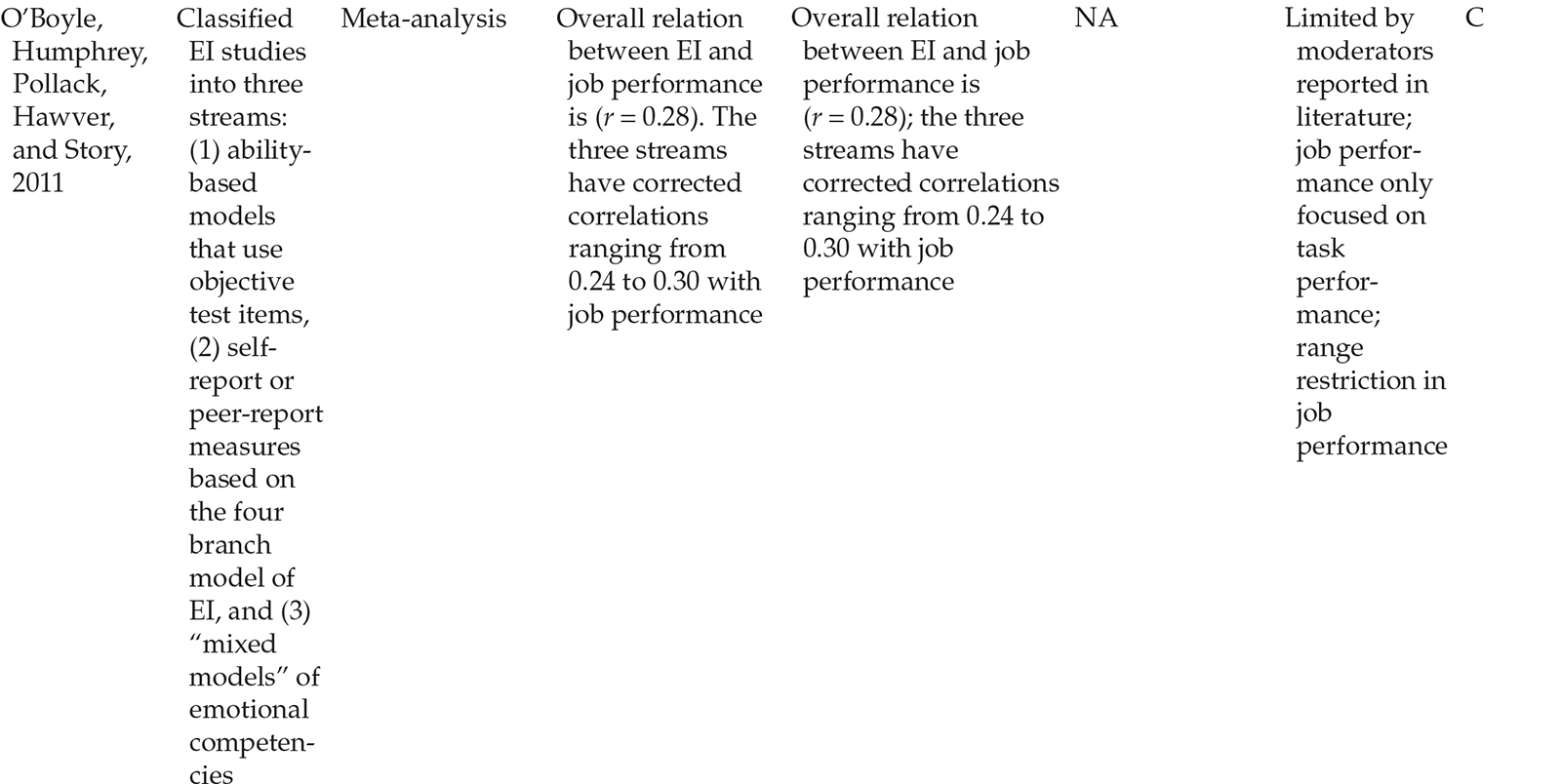

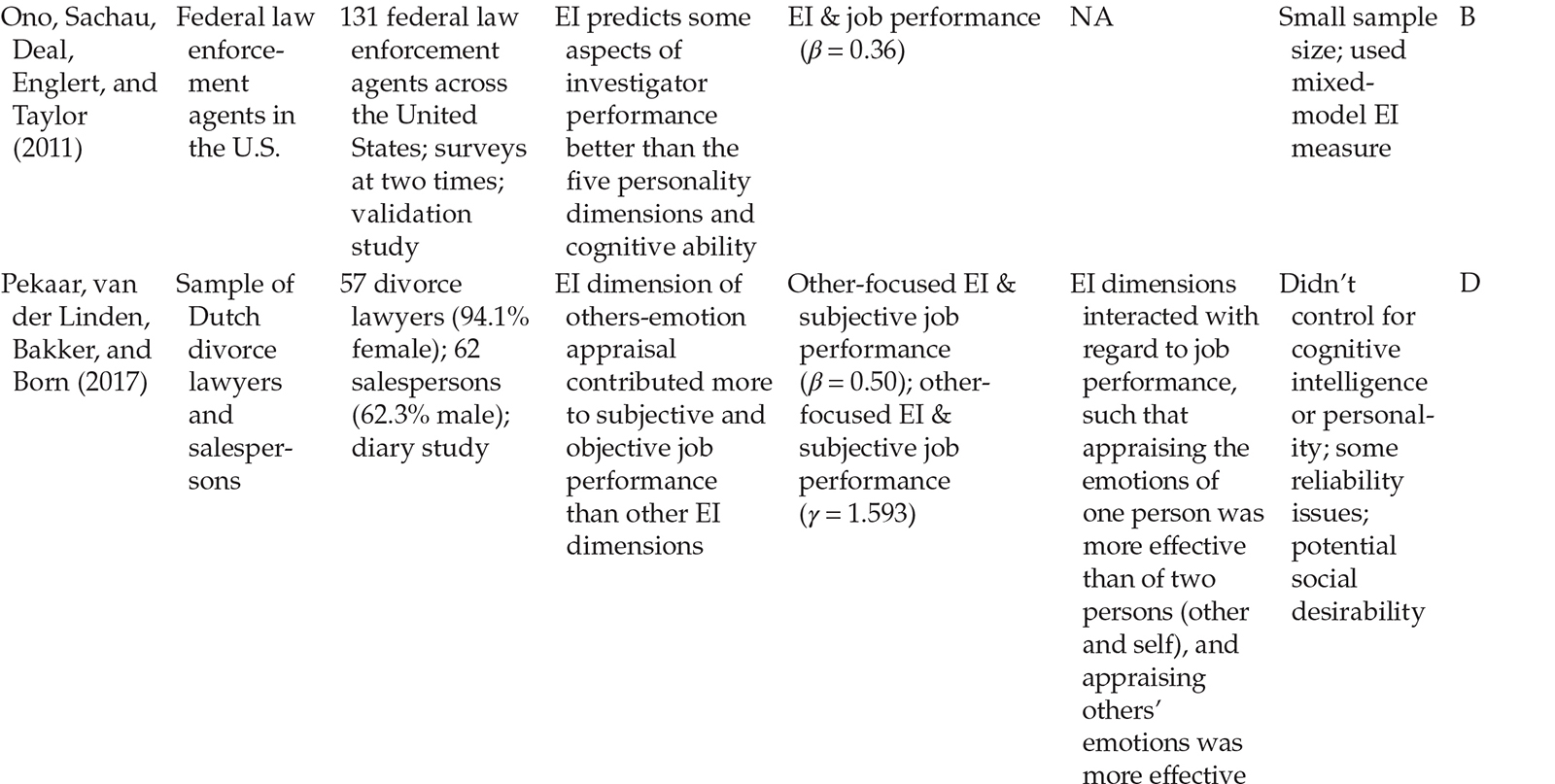

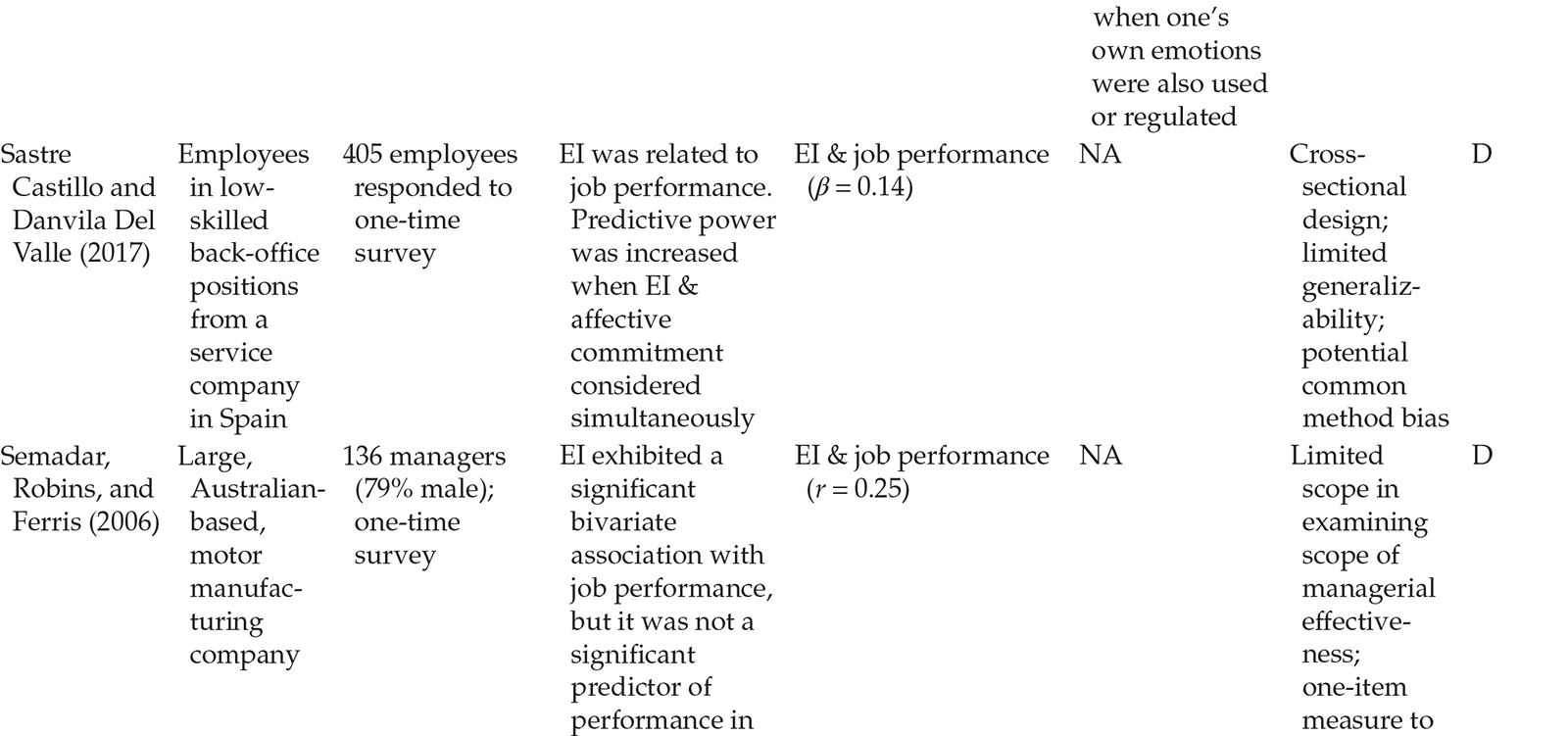

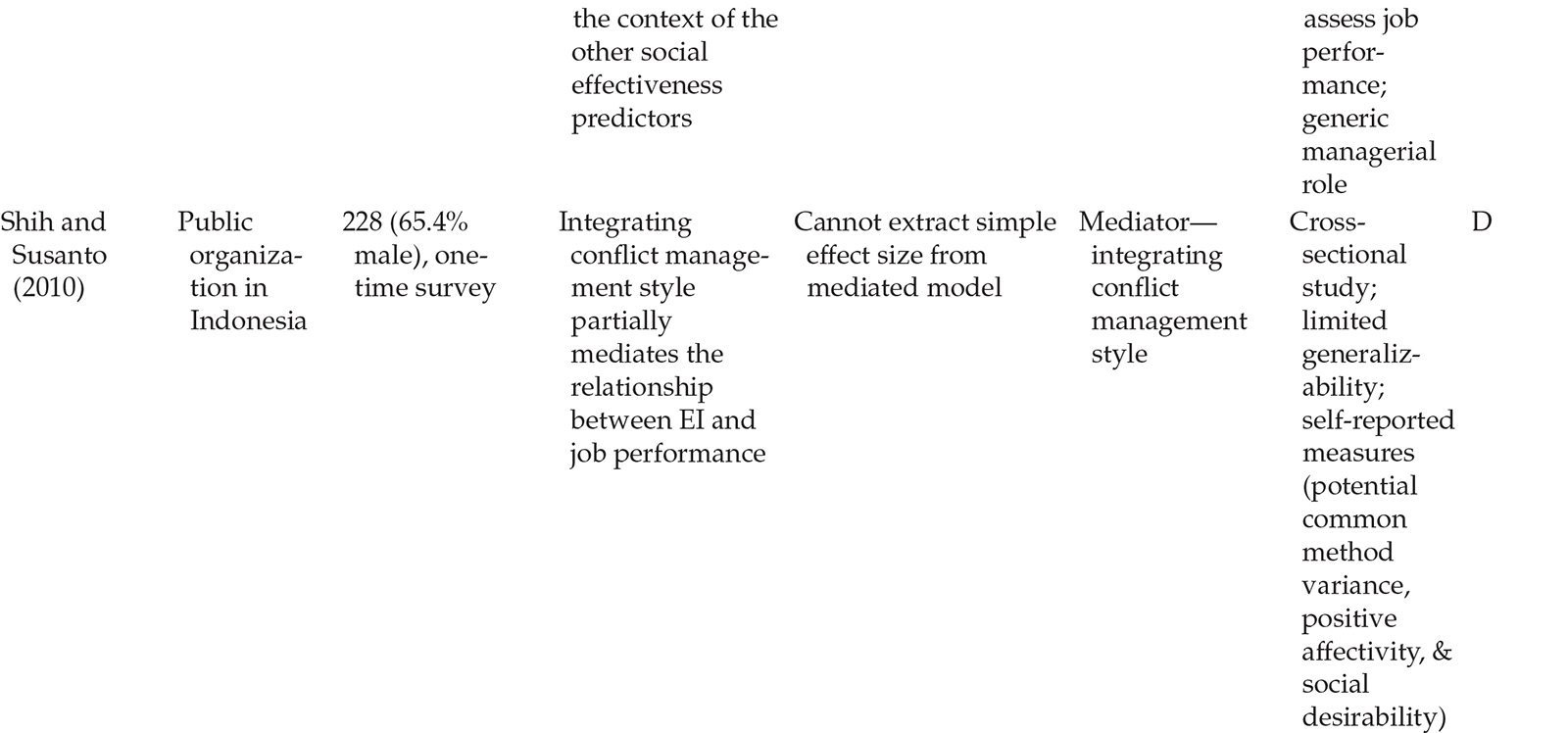

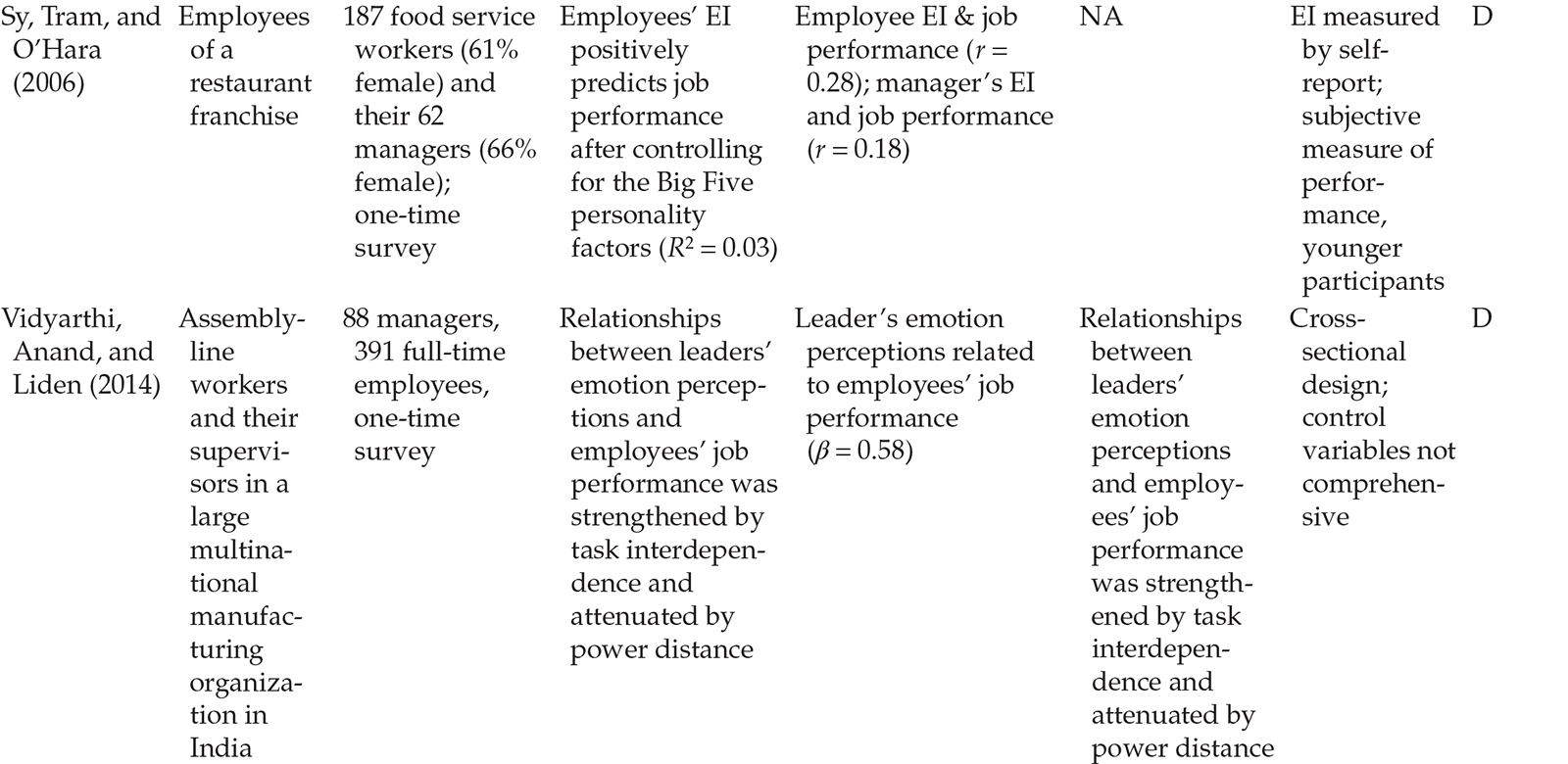

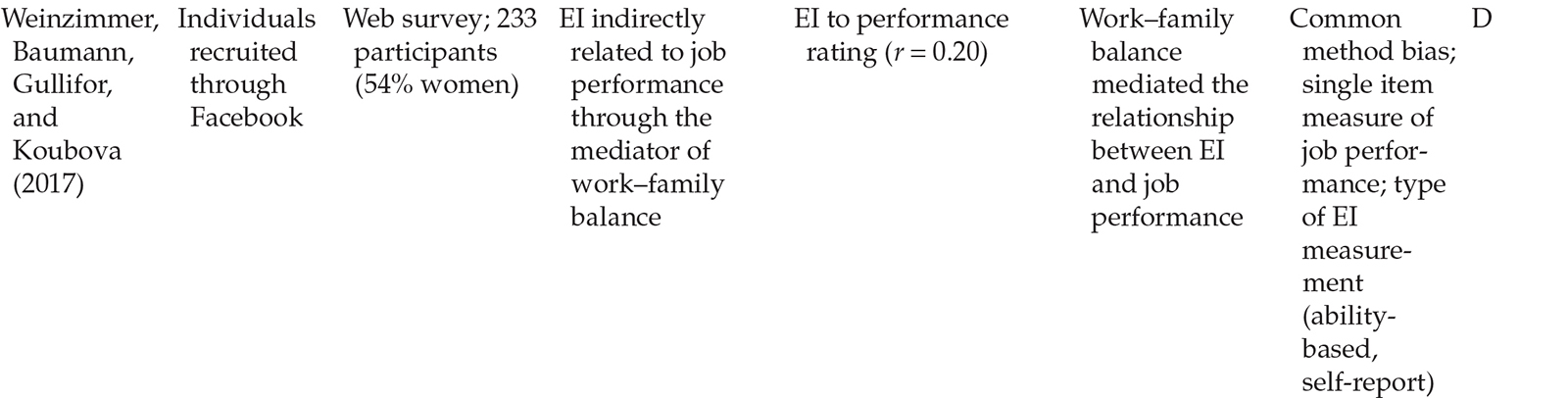

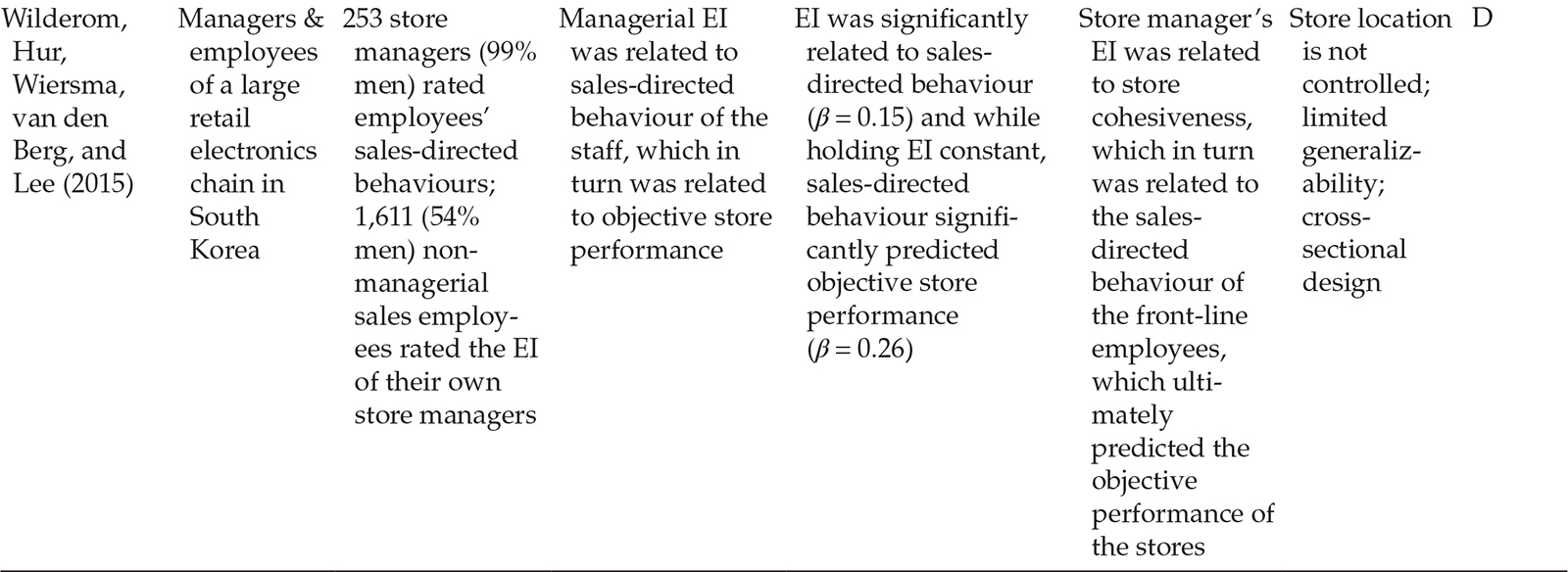

Our search of the three publication databases resulted in 303 peer-reviewed articles. We then eliminated articles (as done by Marler & Boudreau, 2017) in journals that were not on the Journal Quality List (JQL), 63rd edition, July 29, 2018 (Harzing, 2018). Next, we eliminated duplicate articles from our list. For the remaining 27 articles in scholarly peer-reviewed journals, we extracted the following information: (1) author and year of publication, (2) sector/population, (3) design and sample size, (4) main findings, (5) effect size, (6) moderators/mediators, (7) limitations, and (8) design level (using criteria by Barends, Rousseau, & Briner, 2017). See Table 1.1.

Critical evaluation of evidence

In order to answer our research questions, we reviewed the information collected in Table 1.1, as well as examining the retained articles in more detail. We looked for patterns across the studies including: (1) Sector/population—Were the sectors/populations more homogeneous or more heterogeneous in terms of types of participants and countries where participants resided? (2) Design and sample size—Were stronger or weaker research designs used by researchers? Were studies able to provide stronger or weaker evidence for causality when assessing the relationship between EI and job performance? Were samples large or small? (3) Main findings—Was the evidence consistent? (i.e., pointing to identical or similar conclusions?); Was the evidence contested? (one or more study/studies directly refutes or contests the findings of other studies, raising questions about the trustworthiness of the purported effect?); Was the evidence mixed? (studies based on a variety of different designs or methods, applied in a range of contexts, have produced results that suggest underlying difference in the nature of the effects observed or important differences across studies that are not yet well understood?).

Results

Our discussion of results is organised around the key research questions posed at the beginning of the chapter.

Is there a relationship between EI and job performance? If so, how strong is it?

First, how is job performance typically operationalised in EI research? Task performance is the core substantive duties that are formally recognised as part of the job; but in addition to task performance, organisational citizenship behaviours (OCB) or contextual performance concerns activities that contribute to the achievement of the objectives of an organisation, but are not formally recognised (Cote & Miners, 2006). In EI research, objective task performance is rarely measured. More typically, EI research relies upon subjective ratings by managers, and occasionally, ratings by peers/co-workers. A few EI studies take a more expansive view of job performance and include measures of OCB. The best available evidence (from two meta-analyses and by examining the pattern of results in Table 1.1) for the relationship between EI and job performance is that the effect size is about r = 0.28. This is considered a “moderate” relationship by commonly accepted benchmarks of effect sizes (Cohen, 1977).

Table 1.1 Categorisation of peer-reviewed journal publications

Some cautions must be observed in placing confidence in the observed relationships between EI and job performance found in the literature. For example, we concluded the following from our assessment of the studies of the relationship between EI and job performance: (1) Most studies use relatively small sample sizes, most use convenience samples, and typically sample only one group or type of employees. (2) Most studies have limited generalisability; however, (3) even though small convenience samples are typical, when you take into account all of the studies, we found diversity in job types and people across a broad variety of countries. So, while individual studies may have limited generalisability, the collection of studies as a whole provides broader external validity. (4) Typically, EI studies use cross-sectional research designs with one-time surveys. A few studies measured independent and dependent variables at two different times. Consequently, inferences about causality must be viewed cautiously. (5) Most EI studies modelled the relationship between EI and job performance as linear, but one study (Bozionelos & Singh, 2017) found a U-shaped relationship. (6) Many studies are vulnerable to common method bias. (7) Several studies found effects for the relationship between supervisor’s EI on followers’ job performance. (8) While many studies assess the effects of overall EI on job performance, a number of studies also found significant effects for individual dimensions of EI on job performance. (9) A small number of studies used a predictive validation design providing stronger evidence for causality and eliminating alternative explanations.

Does EI incrementally predict job performance when measures of personality and cognitive intelligence are included as predictors?

There is consistent evidence that EI demonstrates incremental validity over other predictors of job performance. Kluemper, DeGroot, and Choi (2013) found that EI consistently demonstrates incremental validity and is the strongest predictor of task performance and individually directed OCB. Ono, Sachau, Deal, Englert, and Taylor (2011) found that EI predicts some aspects of criminal investigator performance better than the five personality dimensions and cognitive ability. Law, Wong, Huang, and Li (2008) found that EI is a significant predictor of job performance beyond the effect of the General Mental Ability (GMA) battery on performance. Sy, Tram, and O’Hara (2006) found employees’ EI positively predicts job performance after controlling for the Big Five personality factors. Blickle et al. (2009) found that EI explained additional variance in overall job performance ratings beyond GMA and personality traits.

What mediates the relationship between EI and job performance?

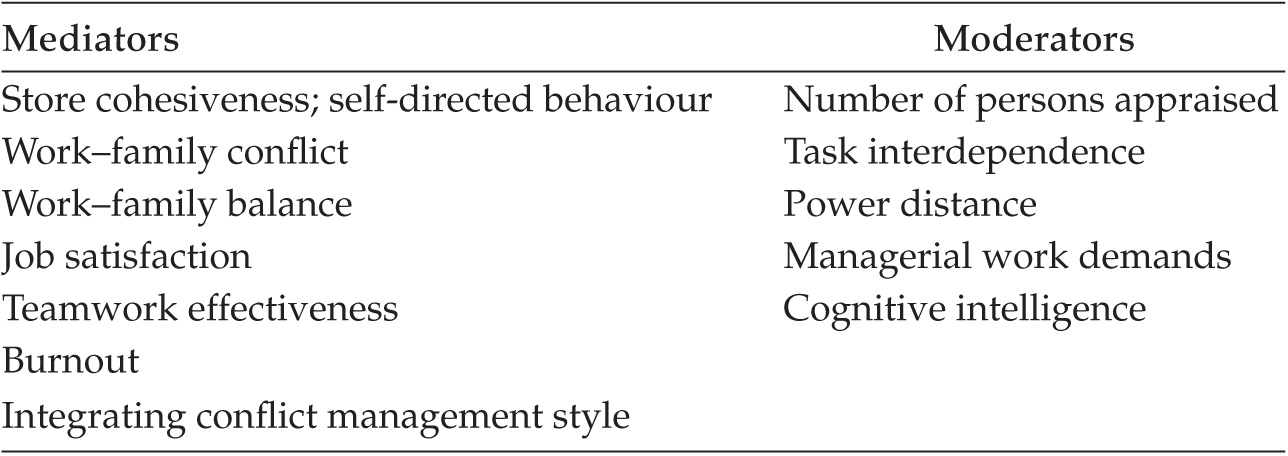

EI seems to affect job performance through several possible mediators (see Table 1.2).

For example, one study found that the relationship between EI and job performance was mediated by teamwork effectiveness in a team environment (Farh, Seo, and Tesluk, 2012). Another study found that integrating conflict management style mediated the relationship between EI and job performance (Shih & Susanto, 2010). Two studies (Carmeli, 2003; Weinzimmer, Baumann, Gullifor, & Koubova, 2017) found that the relationship between EI and job performance was mediated by its effects on work–family conflict and work–family balance.

Several studies examined mediators of particular dimensions of EI. For example, one study found that the dimension regulation of emotion was mediated by job satisfaction in influencing contextual performance (Vidyarthi, Anand, & Liden, 2014). That study also found that job satisfaction mediated the relationship between the EI dimension use of emotion and contextual performance. Another study found that the relationship between the EI dimension use of emotion and work performance was mediated by its influence in lowering burnout (Huang, Chan, Lam, & Nan, 2010). One study found that store managers’ EI was related to store cohesiveness, which in turn was related to the sales-directed behaviour of the frontline employees, which ultimately predicted the objective performance of the stores (Wilderom, Hur, Wiersma, van den Berg, & Lee, 2015).

Table 1.2 Mediators and moderators of the EI→job performance relationship

What moderates the relationship between EI and job performance?

One study found that EI dimensions interacted with regard to job performance, such that appraising the emotions of one person was more effective than appraising the emotions of two persons (other and self), and appraising others’ emotions was more effective when one’s own emotions were also used or regulated. Kim and Liu (2017) found that emotional competence moderates the relationship between taking charge and employees’ job performance, such that the relationship is positive only when emotional competence is high. Vidyarthi, Anand, and Liden (2014) found that relationships between leaders’ emotion perceptions and employees’ job performance was strengthened by task interdependence and attenuated by power distance. Farh, Seo, and Tesluk (2012) found that job context moderates the positive relationship between EI and teamwork effectiveness, such that the relationship is stronger for employees working in job contexts with higher rather than lower managerial work demands (MWD). Huang, Chan, Lam, and Nan (2010) found that one of the EI dimensions moderated the relationship between LMX and work performance such that the link between LMX and work performance was stronger for service workers with higher levels of use of emotion.

Discussion and implications for scientists and engineers

It seems logical to infer that in almost all work settings, individuals have to cooperate with others and do at least some group work tasks (O’Boyle, Humphrey, Pollack, Hawver, & Story, 2011). Furthermore, jobs in the service sector—especially those involving interactions with customers—seem likely candidates for hiring employees with high levels of EI. And, while some scientists and engineers may function as “lone rangers,” fulfilling their job requirements with little or no interpersonal interaction, it is hard to imagine many of those types of jobs in today’s team-oriented work environment. Consequently, working with others in science and engineering project teams requires not only heavy doses of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) knowledge and skills; it also requires the ability to work and cooperate with others, share knowledge, and combine complementary and supplementary skill sets in the production of outcomes. Farh, Seo, and Tesluk (2012) explained that someone with high emotional perception is more likely to recognise when a team member is under significant stress by observing the team member’s emotional cues and, as a result, to assist that team member by offering to off-load some responsibilities and/or make extra efforts to coordinate work activities.

One intriguing study has implications for what organisations might expect from using EI in selection and training for scientists and engineers. Cote and Miners (2006) proposed and tested a compensatory model of EI. Compensatory models propose that a specific ability predicts performance more strongly in a person who lacks other abilities than in a person who has other abilities that are related to performance. Cote and Miners (2006) assert that if compensatory effects exist, EI should predict job performance only some of the time, depending upon other abilities that individuals possess. More specifically, they proposed that cognitive intelligence moderates the association between EI and job performance, such that the association becomes more positive as cognitive intelligence decreases. Thus, if true for scientists and engineers, EI would be more beneficial to those who are lower in cognitive intelligence. This research needs replication in order to provide stronger evidence for organisations to act upon however.

Another study also offers insights into when EI might be important for scientists and engineers. Using trait activation theory (TAT), Farh, Seo, and Tesluk (2012) proposed that traits (in this case EI) more strongly predict trait-relevant behaviour when organisational contexts contain trait-relevant cues, which in turn activate individuals’ traits and cause individuals to behave in ways that are consistent with their standing on those traits. These researchers proposed that the relationship between EI and job performance is strengthened (moderated) in job contexts involving high MWD, or jobs requiring the management of diverse individuals, functions, and lines of business. Therefore, scientists and engineers who are promoted to managerial positions will likely benefit from having higher EI.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have conducted a systematic, evidence-based review of the relationship between EI and job performance. We have found that there is a moderate size effect for that relationship, approximately r = 0.28. Furthermore, EI provides incremental validity in predicting job performance beyond cognitive intelligence and personality factors. While there is a significant relationship between EI and job performance, that relationship can be moderated by a number of factors. Furthermore, the EI and job performance relationship is mediated by a number of factors as well. This information is useful to organisational decision-makers who contemplate measuring EI and using it for decision-making, such as hiring, training, and other human resource activities.

With respect to scientists and engineers, EI seems likely to be an important factor especially in contexts where there is a team environment, such as research and development teams. Furthermore, scientists and engineers who are put into management and leadership positions will likely be more effective if they have higher EI. The only scientists and engineers who may not benefit as much from higher levels of EI are those who work solo and have high cognitive intelligence. But we suspect there are very few of those employees in today’s workplace.

Overall, EI seems to be an important trait with a growing evidence base for its utility in organisations. However, organisational decision-makers will be wise to acquaint themselves with that evidence base and factor that knowledge into how they apply it.

References

Barends, E., Rousseau, D. M., & Briner, R. B. (Eds.). (2017). CEBMa guideline for rapid evidence assessments in management and organisations, Version 1.0. Center for Evidence Based Management, Amsterdam. Available from www.cebma.org/guidelines/

Blickle, G., Momm, T. S., Kramer, J., Mierke, J., Liu, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (2009). Construct and criterion-related validation of a measure of emotional reasoning skills: A two-study investigation. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17(1), 101–118.

Bozionelos, N., & Singh, S. K. (2017). The relationship of emotional intelligence with task and contextual performance: More than it meets the linear eye. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 206–211.

Carmeli, A. (2003). The relationship between emotional intelligence and work attitudes, behavior and outcomes: An examination among senior managers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(8), 788–813.

Christiansen, N. D., Janovics, J. E., & Siers, B. P. (2010). Emotional intelligence in selection contexts: Measurement method, criterion-related validity, and vulnerability to response distortion. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 18(1), 87–101.

Clarke, N., & Mahadi, N. (2017). Differences between follower and dyadic measures of LMX as mediators of emotional intelligence and employee performance, well-being, and turnover intention. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 26(3), 373–384.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cote, S., & Miners, C. T. (2006). Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and job performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 1–28.

Dulewicz, V., Higgs, M., & Slaski, M. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence: Content, construct and criterion-related validity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(5), 405–420.

Farh, C. I., Seo, M. G., & Tesluk, P. E. (2012). Emotional intelligence, teamwork effectiveness, and job performance: The moderating role of job context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 890.

Greenidge, D., Devonish, D., & Alleyne, P. (2014). The relationship between ability-based emotional intelligence and contextual performance and counterproductive work behaviors: A test of the mediating effects of job satisfaction. Human Performance, 27(3), 225–242.

Harzing, A. W. (2018). Journal quality list. Retrieved from https://harzing.com/download/jql-2018-07-subject.pdf

Huang, X., Chan, S. C., Lam, W., & Nan, X. (2010). The joint effect of leader–member exchange and emotional intelligence on burnout and work performance in call centers in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(7), 1124–1144.

Joseph, D. L., Jin, J., Newman, D. A., & O’Boyle, E. H. (2015). Why does self-reported emotional intelligence predict job performance? A meta-analytic investigation of mixed EI. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 298.

Joseph, D. L., & Newman, D. A. (2010). Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 54.

Kim, T. Y., & Liu, Z. (2017). Taking charge and employee outcomes: The moderating effect of emotional competence. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(5), 775–793.

Kluemper, D. H., DeGroot, T., & Choi, S. (2013). Emotion management ability: Predicting task performance, citizenship, and deviance. Journal of Management, 39(4), 878–905.

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., Huang, G. H., & Li, X. (2008). The effects of emotional intelligence on job performance and life satisfaction for the research and development scientists in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(1), 51–69.

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., & Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 483.

Lindebaum, D. (2013). Does emotional intelligence moderate the relationship between mental health and job performance? An exploratory study. European Management Journal, 31(6), 538–548.

Marler, J. H., & Boudreau, J. W. (2017). An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 3–26.

O’Boyle, E. H., Jr., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., & Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 32(5), 788–818.

Ono, M., Sachau, D. A., Deal, W. P., Englert, D. R., & Taylor, M. D. (2011). Cognitive ability, emotional intelligence, and the big five personality dimensions as predictors of criminal investigator performance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(5), 471–491.

Pekaar, K. A., van der Linden, D., Bakker, A. B., & Born, M. P. (2017). Emotional intelligence and job performance: The role of enactment and focus on others’ emotions. Human Performance, 30(2–3), 135–153.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211.

Sastre Castillo, M. Á., & Danvila Del Valle, I. (2017). Is emotional intelligence the panacea for a better job performance? A study on low-skilled back office jobs. Employee Relations, 39(5), 683–698.

Semadar, A., Robins, G., & Ferris, G. R. (2006). Comparing the validity of multiple social effectiveness constructs in the prediction of managerial job performance. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 27(4), 443–461.

Shih, H. A., & Susanto, E. (2010). Conflict management styles, emotional intelligence, and job performance in public organisations. International Journal of Conflict Management, 21(2), 147–168.

Sy, T., Tram, S., & O’Hara, L. A. (2006). Relation of employee and manager emotional intelligence to job satisfaction and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 461–473.

Vidyarthi, P. R., Anand, S., & Liden, R. C. (2014). Do emotionally perceptive leaders motivate higher employee performance? The moderating role of task interdependence and power distance. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 232–244.

Weinzimmer, L. G., Baumann, H. M., Gullifor, D. P., & Koubova, V. (2017). Emotional intelligence and job performance: The mediating role of work-family balance. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157(3), 322–337.

Wilderom, C. P., Hur, Y., Wiersma, U. J., van den Berg, P. T., & Lee, J. (2015). From manager’s emotional intelligence to objective store performance: Through store cohesiveness and sales-directed employee behavior. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 36(6), 825–844.