CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

To define money and explain the functions of money.

To identify the various measures and components of the U.S. money supply and different monetary standards.

To introduce the financial institutions that are important for the maintenance and control of the U.S. money supply, and to highlight commercial banks and commercial bank regulation.

To explain the role of the Federal Reserve system, its organization, and the functions that Federal Reserve banks perform.

To discuss recent legislative and structural changes in the financial institutions system.

We have explored several topics that in one way or another involve money. For example, we learned that economic activity expands or contracts as the size of the spending stream increases or decreases and that with inflation the purchasing power of money deteriorates. Without money, modern economies as we know them could not exist. Even though money does not itself produce goods and services, as do land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship, it makes large-scale production and distribution possible. If a nation's monetary system becomes unstable, adverse economic consequences can result.

In this chapter we will deal with some basics about money, banks and other financial institutions, and the Federal Reserve, which plays an extremely critical role in the functioning of the economy and is regularly covered in the media. While this chapter provides information that may correct some myths for you (for example, money is backed by gold and silver), more importantly, it lays the groundwork for Chapter 8, where we study how money is actually created and destroyed and the effects of money on economic activity.

In recent years, the development and growth of financial services that operate outside of the banking system have created a number of issues for the U. S. macroeconomy, including a serious financial crisis that began in 2007. This chapter touches on these entities and the crisis.

MONEY

The Definition and Functions of Money

Very simply, money is anything that is generally accepted as a medium of exchange. A medium of exchange is something that people are readily willing to accept in payment for purchases of goods, services, and resources because they know it can be easily used for further transactions. In the United States a $10 bill is a medium of exchange because people are willing to take this bill in payment, knowing that it can be used for other purchases.

Money

Anything that is generally accepted as a medium of exchange.

Medium of Exchange

Something that is generally accepted as payment for goods, services, and resources; the primary function of money.

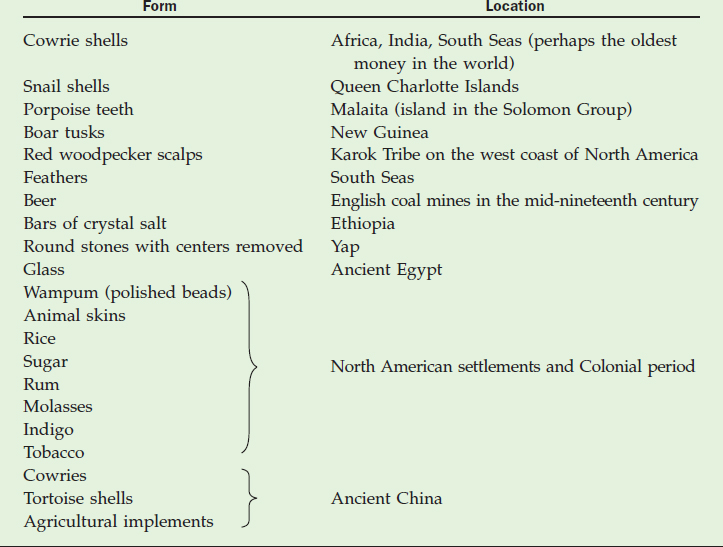

Many people believe that money must be made of precious metal or be backed by a tangible asset, such as gold or silver. This is not true. Because a medium of exchange can be anything, possibilities for money include precious metals, stones, beads, coins, cigarettes, pieces of paper, and electronically transferred numbers. The physical form that money takes makes no difference as long as it is the generally accepted means of payment for purchases in an economy. Some unusual types of money that have been used at different times and in different places are listed in Table 7.1.

If anything can serve as money, how is the value of money determined? Because money is a medium of exchange, the value of any money—a $20 bill, for example—is measured by the goods, services, and resources that it can purchase. Inflation causes the value of money to decline because fewer goods, services, and resources can be purchased with the same amount of money. Small, incremental increases in the general level of prices or serious bouts of inflation will cause a decline in the value of money: The decline can happen gradually or be a quick, significant deterioration.

Value of Money

Measured by the goods, services, and resources that money can purchase.

What would happen if there were no money—no generally accepted means of payment? In the absence of a medium of exchange, a barter system would develop. With barter, a direct exchange of goods and services occurs: A student might exchange some camping gear in return for a psychology textbook. With barter, people have to expend a lot of energy locating someone willing to take what they offer in trade for what they want. In today's world, few people operate on a barter system since it is virtually impossible to have much economic development by trading in this manner. A medium of exchange, or money, removes the problems of barter.

Barter System

System in which goods and services are exchanged for each other rather than for money.

TABLE 7.1 Different Forms of Money

Anything can serve as money in a society, provided it is generally accepted as payment for goods, services, and resources.

Source: Norman Angell, The Story of Money (Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishing Co., 1929), pp. 73–76, 78–80, 82, 84, 85, 88–90.

While money serves primarily as a medium of exchange, it also performs two additional functions: It is a measure of value, and it provides a method for storing wealth and delaying payments. Every nation's money is expressed in terms of a base unit. In the United States, the base unit is the dollar; in Japan, the yen; and in many countries belonging to the European Union, the euro. With a base unit, the value of every resource, good, and service can be expressed in terms of that unit: A house, for example, might be worth 220,000 times a dollar unit ($220,000) and a car 22,000 times the unit ($22,000). Money's function as a base unit makes it easy to create simple comparisons among the values of goods and services, and the ability to express those values in terms of a common measure greatly reduces the information needed to make economic decisions.

Measure of Value

A function of money; the value of every good, service, and resource can be expressed in terms of an economy's base unit of money.

Method for Storing Wealth and Delaying Payments

A function of money; allows for saving, or storing wealth for future use, and permits credit, or delayed payments.

Money also provides a method for storing wealth: It allows us to accumulate wealth or income to use in the future. For example, the $100 bill you have had since 2008 will still add one hundred dollars to your bank account balance when handed to a teller for deposit sometime in the future. With money, we can save from our current income, and a system of lending and borrowing is possible. It is this function that is critical to a stable economy.

APPLICATION 7.1

FIXED ASSETS, OR: WHY A LOAN IN YAP IS HARD TO ROLL OVER

FIXED ASSETS, OR: WHY A LOAN IN YAP IS HARD TO ROLL OVER

Yap, Micronesia—On this tiny South Pacific island, life is easy and the currency is hard.

Elsewhere, the world's troubled monetary system creaks along…. But on Yap the currency is as solid as a rock. In fact, it is rock. Limestone to be precise.

For nearly 2,000 years the Yapese have used large stone wheels to pay for major purchases, such as land, canoes and permission to marry. Yap is a U.S. trust territory, and the dollar is used in grocery stores and gas stations. But reliance on stone money … continues.

Buying property with stones is “much easier than buying it with U.S. dollars,” says John Chodad, who recently purchased a building lot with a 30-inch stone wheel. “We don't know the value of the U.S. dollar.” Others on this 37-square-mile island 530 miles southwest of Guam use both dollars and stones. Venito Gurtmag, a builder, recently accepted a four-foot-wide stone disk and $8,700 for a house he built in an outlying village.

Stone wheels don't make good pocket money, so for small transactions, Yapese use other forms of currency, such as beer. Beer is proffered as payment for all sorts of odd jobs, including construction….

Besides stone wheels and beer, the Yapese sometimes spend gaw, consisting of necklaces of stone beads strung together around a whale's tooth. They also can buy things with yar, a currency made from large sea shells. But these are small change.

The people of Yap have been using stone money ever since a Yapese warrior named Anagumang first brought the huge stones over from limestone caverns on neighboring Palau, some 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. Inspired by the moon, he fashioned the stone into large circles. The rest is history.

Yapese lean the stone wheels against their houses or prop up rows of them in village “banks.” Most of the stones are 2 1/2 to five feet in diameter, but some are as much as 12 feet across. Each has a hole in the center so it can be slipped onto the trunk of a fallen betel-nut tree and carried. It takes 20 men to lift some wheels.

By custom, the stones are worthless when broken. You never hear people on Yap musing about wanting a piece of the rock. Rather than risk a broken stone—or back—Yapese tend to leave the larger stones where they are and make a mental accounting that the ownership has been transferred….

The worth of stone money doesn't depend on size. Instead, the pieces are valued by how hard it was to get them here….

There are some decided advantages to using massive stones for money. They are immune to black-market trading, for one thing, and they pose formidable obstacles to pickpockets. In addition, there aren't any sterile debates about how to stabilize the Yapese monetary system. With only about 6,600 stone wheels remaining on the island, the money-supply level stays put. “If you have it, you have it,” shrugs Andrew Ken, a Yapese monetary thinker.

But stone money has its limits. Linus Ruuamau, the manager of one of the island's few retail stores, won't accept it for general merchandise. And Al Azuma, who manages the local Bank of Hawaii branch, the only conventional financial institution here, isn't interested in limestone deposits or any sort of shell game. So the money, left uninvested, just gathers moss.

But stone money accords well with Yapese traditions. “There are a lot of instances here where you cannot use U.S. money,” Mr. Gurtmag says. One is the settling of disputes. Unlike most money, stones sometimes can buy happiness, of a sort; if a Yapese wants to settle an argument, he brings his adversary stone money as a token. “The apology is accepted without question,” Mr. Chodad says. “If you used dollars, there'd be an argument over whether it was enough.”

Source: Reprinted by permission of The Wall Street Journal, Copyright © 1990 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. License number 2167141466402.

If there is a question about the future acceptability of what today we call money, people might be unwilling to save and institutions unwilling to lend for investment or other purposes. A bank might be reluctant to make a student loan or lend a developer millions of dollars this year if there were questions about the usability of future repayments.

The functions of money, as well as some of the types of money described in this section, are illustrated in Application 7.1, “Fixed Assets, Or: Why a Loan in Yap Is Hard to Roll Over.”

The Money Supply

Every economy has a supply of money that is used to carry out transactions. What makes up the money supply of the U.S. economy and how large is this supply? This is a more difficult question than it appears to be since people look at what is actually money in different ways. For example, some people think that a savings account is money while others do not. As a result, we have two different official definitions of the money supply, with one broader than the other because it includes additional components.

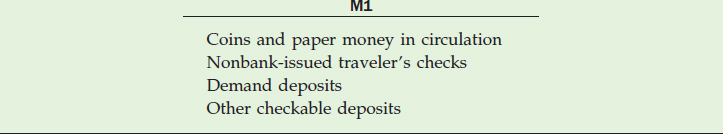

TABLE 7.2 The U.S. Money Supply: M1

M1 is the narrower definition of the U.S. money supply.

Source: Federal Reserve, “Money Stock Measures,” http://www.federalreserve.gov/Releases/H6/Current/, April 19, 2012.

The narrower definition of the money supply is called M1. The components of this definition are listed in Table 7.2: coins and paper money in circulation, nonbank-issued traveler's checks, almost all demand deposits (checking accounts) at commercial banks, and accounts called other checkable deposits.1

M1

Narrower definition of the U.S. money supply; includes coins and paper money in circulation, some traveler's checks, most demand deposits, and other checkable deposits.

Components of M1 In the U.S. economy, coins, which are issued by the U.S. Mint, are token money: The value of the metal in the coin is less than the face value of the coin. If this were not the case, coins might disappear from circulation. For example, in the past, when the price of copper increased to a level where a penny contained almost one cent worth of copper, pennies became short in supply. Today, pennies are made almost entirely of zinc. Information about U.S. coins—history, composition, and more—can be found at www.usmint.gov.

Token Money

Money with a face value greater than the value of the commodity from which it is made.

Paper money constitutes a larger share of our money supply than coins. Almost all U.S. paper money is Federal Reserve Notes. (Notice the inscription on the top of a paper bill that states “Federal Reserve Note.”) Federal Reserve banks, which will be discussed shortly, issue and back this paper money. Coins and paper money make up currency.

Federal Reserve Notes

Paper money issued by the Federal Reserve banks; includes almost all paper money in circulation.

Currency

Coins and paper money.

Traveler's checks, which can be used in the United States or abroad, are purchased from banking organizations as well as from American Express and other companies. However, only traveler's checks from “nonbank issuers” are categorized separately in M1, and these constitute the smallest component of M1.

The demand deposit component of the money supply is checking account balances kept primarily at commercial banks. These deposits include small balances kept by individuals as well as large sums kept by businesses and nonprofit institutions for payroll and other payment purposes. Demand deposits are merely bookkeeping numbers. When a check or online payment is deposited or one is written and cleared, numbers are transferred from one set of records or computer entries to another. Because demand deposits are a large portion of the U.S. money supply, we need to realize that much of the money supply is simply numbers in accounts. Some people might think that checks themselves are money, but they are not. A check is just a piece of paper that gives a bank the authority to transfer funds in an account to someone else or to cash.

Demand Deposits

Checking account balances kept primarily at commercial banks.

TABLE 7.3 Currency, Traveler's Checks, Demand Deposits, and Other Checkable Deposits (Billions of Dollars)a

Currency has surpassed demand deposits and other checkable deposits as the largest component of the M1 money supply.

Source: Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), Tables B-1, B-69, B-70.

Other checkable deposits are similar to demand deposits but offer interest on the funds in these accounts. The distinction between these and demand deposits is made for technical reasons. Most of us, including merchants, utility companies, and other payment receivers, pay almost no attention to the distinction among checks, drafts, withdrawal orders, or other technical names given to these accounts. These accounts were introduced in the early 1980s and are provided by banks and other depository institutions.

Other Checkable Deposits

Interest-bearing accounts similar to demand deposits offered by financial depository institutions.

Table 7.3 gives the amount of each component of the M1 money supply as well as other important money-related information. Notice that before 2000 checking-type accounts (demand deposits and other checkable deposits together) were the largest part of M1. People tended to pay for large, expensive items, like a big-screen TV, or to pay rent with a check associated with one of these types of accounts. Employers typically paid their bills and employees with a check.

After 2000, data show that the currency component of M1 has grown significantly, and in some cases it has been the largest component. Some of the early impetus for the reliance on cash for payments came with the Y2K scare when people feared that a major computer crash would occur on January 1, 2000, and bank records would be lost. Since then a number of changes in banking have occurred: ATM machines are popular and can be easily found on street corners, in stores, and just about everywhere; bank money market accounts provide limited checking abilities and higher interest rates causing people to use them for large purchases; there is an increased reliance on credit cards rather than writing out a check for everyday spending; and businesses have found ways to keep their funds in interest-bearing non M1 components and transfer them to demand deposits when needed.

Notice the column in Table 7.3 that shows the total M1 money supply for each year as a percentage of that year's GDP. Every year the total amount spent on new goods and services exceeds the amount of money in circulation. For example, the money supply in 2010 was equal to only 12.7 percent of the total expenditures made on new goods and services that year. Obviously, so much output can be purchased with so few dollars because the same dollars are spent several times over during the course of the year.

TABLE 7.4 The U.S. Money Supply: M2

M2 is the broader definition of the U.S. money supply

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “The Components of the Monetary Aggregates,” The Federal Reserve System: Purposes and Functions, Washington, DC, 9th edition, p. 22.

The average turnover of the money supply in relationship to annual GDP is termed the velocity of money. That is, velocity measures the average number of times a dollar is spent during a year as it is used for the purchase of new goods and services. The far right-hand column of Table 7.3 gives the velocity of M1. Notice that from 1985 to 2000 velocity fluctuated very little: The average dollar was spent about seven times a year. This should be no surprise: We are fairly consistent about the frequency of receiving paychecks and making major payments. However, velocity jumped in 2000 but lessened again in 2010.2

Velocity of Money

Average number of times the money supply is turned over in a year in relationship to GDP.

M2: The Broader Definition of the Money Supply As we said, there are differing opinions as to what constitutes money and because of this two definitions of the money supply are used. M1 is considered by many to be too narrow, especially with the growth of new types of accounts not included in M1 that can be used to buy goods and services or readily converted to payment instruments. Suppose a person receives a paycheck for $1,000 and puts $500 into a demand deposit account, $200 into a savings account, and $300 into a money market deposit account that pays interest and allows limited checking privileges. According to the definition of M1, only the $500 deposited in the checking account would be considered money. Although the funds in the savings account are easily transferable to a checking account or cash and the funds in the money market deposit account can be spent, they are not counted in M1.

The broader definition of the money supply, M2, is given in Table 7.4. Notice that it builds on M1, adding money market deposit accounts, savings deposits, certificates of deposit (time deposits) of less than $100,000, and some money market funds. M2 is considered by many observers to be an important measure of the money supply because it includes money market deposit accounts that allow limited checkable transactions and savings and time deposits that can be easily converted to spendable funds.

M2

M1 plus savings and small-denomination time deposit accounts, money market deposit accounts, and other financial instruments.

In other words, many of the components have a high degree of liquidity. Not surprisingly, there is a substantial difference in the sizes of M1 and M2. At the beginning of 2012, M1 was $2.2 trillion and M2 was $9.8 trillion.3

Liquidity

Ease of converting an asset to its value in cash or spendable funds.

Monetary Standards People are often curious and sometimes concerned about what backs our money and that of other countries. Economies have monetary standards, or designations, for the backing of their money supply. An economy in which money is backed by something of tangible value, such as gold or silver, is on a commodity monetary standard. If the money is backed by gold, the economy is on a gold standard; if it is backed by silver, the economy is on a silver standard.

Commodity Monetary Standard

An economy's money is backed by something of tangible value, such as gold or silver.

For much of its history, the U.S. economy was on a commodity standard. Prior to 1933 the United States had a gold-coin standard, where gold not only backed the money supply but also freely circulated in the hands of the public. The use of gold pieces as money was common. Then, U.S. citizens were asked to turn their gold in to the government, and in 1934 the United States went on a gold-bullion standard. This meant that gold backed the money supply but was no longer available to the general public. Under this gold-bullion standard, however, foreign holders of dollars were paid in gold. In the years after 1950, more and more international debts were paid in gold, and the U.S. gold supply gradually diminished. This brought about a reduction in the gold backing of the money supply. By 1971, official U.S. gold reserves had decreased to the point where the gold supply was frozen. U.S. gold was to be made available to no one, and the dollar was no longer to be converted to gold, not even to settle international transactions.

Since 1971, the U.S. economy has been on a paper monetary standard. This means that money itself has little or no intrinsic value and that it does not represent a claim to any commodity, such as gold or silver. What backs paper money is the strength of the economy, the willingness of people to accept the money in exchange for goods and services, and faith and trust in the purchasing power of the money.

Paper Monetary Standard

An economy's money is not backed by anything of tangible value such as gold or silver.

What is better for an economy, a paper standard or a commodity standard? It is easy to argue that there is more faith in money if it is backed by gold or silver, but history does not bear this out. In the past, panics and monetary crises have occurred even when money was backed by a precious metal. In fact, the knowledge that paper money can be converted into gold or silver can make people act more dramatically on their fears.

But the most important reason that advanced economies turn to a paper standard is that the amount of gold or silver a nation possesses generally has very little to do with its economic needs and potential. It is much more important that the amount of money in an economy be tied to the country's economic conditions rather than the availability of a commodity like gold or silver. But there is always a warning with a paper standard. The administrators of the money supply must be informed and impeccably trustworthy in the decisions they make concerning the money supply and carefully manage it. Without proper controls, serious economic problems can arise.

FINANCIAL DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS

In the United States, there are organizations called financial depository institutions (FDI) that play an extremely important role in the economy because of their association with the money supply. To be classified as an FDI, two functions must be performed: accept and maintain deposits, and make loans. Commercial banks are the most important of the financial depository institutions, but thrifts like savings associations and credit unions are also among these organizations. While they may seem similar to us, they are different in the kinds of deposits and loans they are permitted to offer and the degree of regulation they face.

Financial Depository Institution

Institution that accepts and maintains deposits, and makes loans; can create and destroy money.

Financial depository institutions are vital to the economy because they have the ability to create and destroy money. Here is one of our myths to correct. Many people think that money is created only when currency is printed. This is not so. Money is created when loans are made by financial depository institutions and destroyed when loans are repaid. The process for doing this will be thoroughly explored in the next chapter. For now we want to let you know that these institutions, with their special abilities to accept deposits and make loans, are central to expanding and contracting the money supply.

Commercial Banks

The primary financial depository institution is the commercial bank—where most individuals, businesses, and nonprofit organizations do their banking. A commercial bank attracts deposits by offering checking accounts, or demand deposits, as well as other deposit arrangements, makes loans to businesses and individuals, and performs a number of other functions. Banks earn profit for their owners by attracting deposits and converting them to interest-earning assets such as loans. In 2011, there were about 6,300 commercial banks and 83,000 branches in the United States.4

Commercial Bank

Institution that holds and maintains checking accounts (demand deposits) for its customers, makes commercial (business) and other loans, and performs other functions.

In 1980, Congress passed a significant piece of banking legislation that leveled the playing field for most financial institutions and made them almost indistinguishable: the Monetary Control Act of 1980. Before this act, the ability to make loans to businesses was held almost exclusively by commercial banks.

We saw in Table 7.3 that in 2010 approximately 28 percent of M1 was in demand deposits, or checking accounts, at commercial banks. In addition, commercial banks held some portion of other checkable deposits as well as trillions in savings and time deposits. The huge dollar value of these deposits makes commercial banks the most important of all financial depository institutions.

Commercial Bank Regulation Commercial banks are unique: They are profit-driven businesses but play an essential role in maintaining and changing the size of the U.S. money supply. Since their actions are key to the economy, we must ensure that commercial banks be sound and secure, and not abuse their money-creating abilities. To accomplish this aim, a number of agencies set standards and regulations for commercial banks that include, for example, the backing needed for deposits, the allowable riskiness of loans, and the money capital necessary to open a bank.

All commercial banks must be incorporated, or have a corporate charter. Because both the federal and state governments have the right to charter banks, the United States has a dual banking system: That is, a bank may be chartered by the federal government or by a state government. Federally chartered banks are called national banks, and state-chartered banks are simply called state banks.

Dual Banking System

Label given to the U.S. banking system because both the federal and state governments have the right to charter banks.

National Bank

Commercial bank incorporated under a federal rather than a state charter.

State Bank

Commercial bank incorporated under a state charter.

While bank regulation appears to be scattered among several agencies, there is order among them to prevent duplication of bank-examining tasks and an exacerbation of the disruption that comes with a visit from the examiners. The following gives the various agencies with which a bank may have to deal.

- Charter Authority. The charter sets up the first line of regulation: National banks are regulated by a federal agency and state banks by a state banking agency.

- The Federal Reserve. The Fed, which we will discuss shortly, has various levels of regulatory authority. The Federal Reserve regulates its own members, which include all national banks (they must belong) and state banks that choose to belong, or become “state member banks.” The Federal Reserve also imposes some uniform regulations on all commercial banks extending its authority and lessening the distinction between Federal Reserve member and nonmember banks.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Additional regulation comes from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which was established in 1933 and insures deposits in commercial banks up to a specified amount. All national and state member banks are insured and nonmember state banks may affiliate with the FDIC. Relatively few banks are nonmember noninsured state banks.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

Government agency established in 1933 to insure deposits in commercial banks up to a specified amount.

Bank Failures With such extensive regulation, can banks fail? Banks are no different from other businesses that no longer have the assets necessary to pay their debts. Despite regulation, banks and other financial depository institutions have found themselves in this same bankruptcy-prone position.

Bank failure is easy to understand with some basic accounting terminology. Recall that the two functions of a financial depository institution are to make loans and to hold deposits. The loans of a bank are a major asset (what the bank owns), and its deposits are a major liability (what the bank owes). The net worth of a bank is its assets minus its liabilities.

Asset

Something that an individual or business owns; can be used to cover liabilities.

Liability

A claim on assets; an obligation or a debt of an individual or a business.

Net Worth

Assets minus liabilities; the monetary value of a business.

A bank fails when its assets are no longer sufficient to cover liabilities that must be paid. This is usually the result of heavy loan losses combined with deposit withdrawals. For example, if a bank loans a developer $50 million to build a subdivision of homes, the bank has an asset of $50 million. If the developer goes belly up, perhaps unable to sell the homes in various stages of construction, the bank becomes the new owner of those homes. It will likely not receive the full $50 million it loaned as it tries to dispose of this construction project. In short, the bank is “stuck” with an asset of less than $50 million, or has taken a loan loss. This has been the situation with banks that in recent years have had many houses and properties in foreclosure: They cannot recoup the amounts they loaned.

When a bank's assets decline, it has fewer funds available for depositors who want to withdraw their money from the bank; in other words, it cannot meet the demands of the holders of its liabilities. If a bank has made too many bad loans, it may simply not be solvent. With an insured bank in this position, the FDIC steps in and guarantees that depositors with accounts of less than a specified amount will receive their money. With an uninsured bank, depositors have no such promise, and their funds may be lost.

APPLICATION 7.2

AM I COVERED?

AM I COVERED?

Sally took her $1,000 paycheck to her bank, deposited it into her checking account, and went home. Ed took his $1,000 paycheck to his bank, cashed it for ten $100 bills, and took them home and buried them in his backyard. The next day Sally's bank failed and closed, and an earthquake dropped Ed's backyard and stash of hundred-dollar bills into the Pacific Ocean. Ed lost all of his money, but what about Sally? If Sally's account is in a bank insured by the FDIC, she will likely get all her money covered by the insurance back within a few days following the bank's closing. Since the FDIC began in 1933, customers of failed banks have gotten all of their insured money back.

Is everything you put in an insured bank automatically protected by the FDIC? No. There are certain restrictions on what and how much is protected. Funds in checking or savings accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), money market funds, and some retirement accounts and trusts are insured. But if you use your insured bank to buy U.S. Treasury securities or invest in mutual funds made up of a variety of corporate stocks or other investment products, that money is not insured by the FDIC. Also, and perhaps not surprisingly, the FDIC does not protect the contents of your safe deposit box if it is crushed or burned, or protect you if you are a victim of identity theft.

Also, simply having an account in an FDIC-insured institution does not mean that you will get all your money back if something goes wrong: There are limits on the amount insured. If you have one or more insured accounts in only your name at an FDIC-protected bank, the maximum you can recover is $250,000. If you have a checking account with a balance of $50,000, you'll get $50,000 back. But if one or more accounts together have balances over $250,000, when the bank fails you'll only get $250,000.

There is a way to get more than $250,000 in protection from an FDIC-covered bank—put the funds into a joint account where two or more people have equal rights to the funds, such as an account in the name of a husband and wife. In this case, the maximum protection would be $500,000 ($250,000 for each named account holder). There are also some reimbursement rules about retirement accounts, trusts, and such.

What might you want to do if you inherit some money or you cash a hot stock tip that brings the total balance of your accounts in an FDIC-insured bank over the maximum insurable amount? Your best bet might be to open an account for some of your funds at another FDIC-insured bank—and probably not convert the funds into cash that is buried in your yard!

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, http://www.fdic.gov/deposit.

The number of bank failures in the United States took a serious upturn during the financial crisis that began in 2008 (which will be covered shortly). From 2000 until 2008, there were few failures with just three failures in most years. But in 2009, 2010, and 2011, there were a total of 389 failures. As just explained, in these cases assets could not meet the liabilities. These banks were located throughout the country and in most instances were acquired by another bank. While these numbers are serious, they do not approach the record number of bank failures during the Great Depression—for example, 4,004 in 1933 alone.5

Application 7.2, “Am I Covered?,” gives some information on how the FDIC protects people with accounts in banks. There is valuable information here as many people invest their funds in various instruments that are not insured and find themselves in trouble when their money becomes worth less.

Other Financial Depository Institutions

Other financial depository institutions that play an important role with the money supply are thrift institutions, such as savings associations and banks, and credit unions. In 2010, there were 1,128 insured savings institutions and 7,339 credit unions. Although the number of these institutions is larger than the number of commercial banks, their total size is smaller. In 2010, assets of all savings institutions and credit unions together were just 18 percent of commercial bank assets.6

In the early 1980s, significant changes were made in the legislation regulating these institutions to permit them to offer a greater variety of deposit accounts, to make different types of loans, and to bring some aspects of their operations under Federal Reserve control. The deregulation of deposits and loans, however, caused a serious crisis in the savings and loan industry, requiring financial intervention from the government.

The future of some of these financial depository institutions remains unclear. The number of thrifts and credit unions has fallen in recent years. The closing and merging of failing savings banks, switches from a savings to a commercial bank charter, and the acquisition of savings institutions by commercial banks have all contributed to this movement.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

While the Federal Reserve is familiar to us through media coverage, many people are unaware of the considerable power and authority that it has over our money and the economy. A paper monetary standard, like the one under which we operate, requires careful control. That job has been given to the Federal Reserve. And, as we will learn in Chapter 8, through its control of the supply of money the Fed has the ability to influence levels of employment and prices and affect unemployment and inflation problems.

Created in 1913, the Federal Reserve system has been charged to

- oversee the money supply and adjust its size to meet the needs of the economy,

- coordinate commercial banking operations, and

- regulate some aspects of all depository institutions.

Prior to the creation of the Fed, there was little central organization, a hodgepodge of state and federal banking laws, a history of questionable banking practices, and a recurrence of monetary panics.

Federal Reserve System

Coordinates commercial banking operations, regulates some aspects of all depository institutions, and oversees the U.S. money supply.

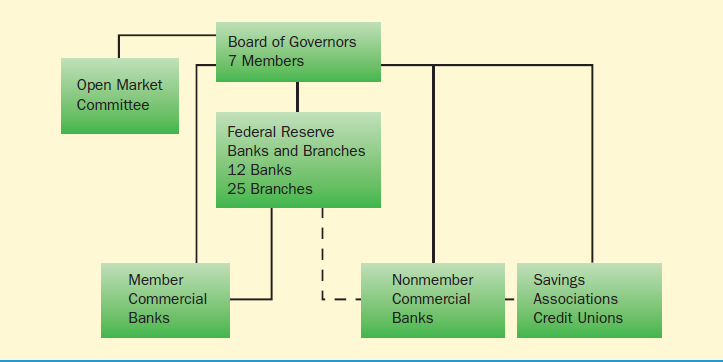

Organization of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve system is organized on both a functional and a geographic basis. Figure 7.1 outlines the important features in the system's functional structure. The system is headed by the seven-member Board of Governors, each appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate for a 14-year term.7 One member is designated by the president as chairperson and serves as the spokesperson for Federal Reserve policy. Ben Bernanke has been the well-known and carefully watched chair of the Board since January 2006.

Board of Governors

Seven-member board heading the Federal Reserve System; develops policies concerning money, banking, and other financial institution practices.

The Board of Governors has duties and responsibilities typical of a board of any organization: It sets goals and objectives for carrying out its charge and appropriate policies to meet them. The Open Market Committee, which includes the Board of Governors among its members, carries out the most important procedure for money supply control: It authorizes the buying and selling of government securities by the Federal Reserve.8 You can go to the Federal Reserve Web site, www.FederalReserve.gov, for the pictures and biographies of the current members of the Board of Governors.

Open Market Committee

Oversees the buying and selling of government securities by the Federal Reserve System.

FIGURE 7.1 Functional Structure of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is headed by the Board of Governors, and many system activities are carried out through the Federal Reserve banks and their branches.

At the center of the Federal Reserve system are 12 Federal Reserve banks and their 24 branches, located throughout the country. These are not commercial banks: They deal with commercial banks and other financial depository institutions and perform a variety of functions that will be covered shortly. Each Federal Reserve bank is an independent corporation with its own board of directors, and each bank carries out the same functions. The remainder of the Federal Reserve system is the country's financial depository institutions, which are influenced by Federal Reserve policies, and may depend on the Fed for certain services.

Federal Reserve Banks

Twelve banks that deal with commercial banks and other financial institutions.

The Fed is also organized geographically. The United States is divided into 12 Federal Reserve districts, each represented by a Federal Reserve bank that is responsible for its own branch banks and the member commercial banks in its geographic area. Figure 7.2 illustrates the 12 Federal Reserve districts. In what district do you live, and how close are you located to one of these banks?

Functions of the Federal Reserve Banks

What do the Federal Reserve banks do? The Federal Reserve banks and their branches perform a variety of functions that do not directly involve the typical commercial bank customer. In fact, there is little reason for the average individual or businessperson to ever enter a Federal Reserve bank.

Supervise and Examine Member Banks One function of each Federal Reserve bank is to supervise and examine member banks within its district. For this purpose, each Federal Reserve bank employs a staff of examiners who periodically check each member bank's financial condition and compliance with system regulations.

FIGURE 7.2 Federal Reserve Districts

The United States is divided into 12 Federal Reserve districts, each with its own Federal Reserve bank.

Source: Federal Reserve Bulletin, Spring 2005, p. 312.

Maintain Reserve Accounts Another Federal Reserve bank function is to maintain reserve accounts for financial depository institutions. A reserve account is a deposit in the name of a financial institution that is held at a Federal Reserve bank or other approved place. Financial depository institutions must have a reserve account and hold a minimum amount on reserve. However, the actual amount fluctuates daily and may exceed the minimum.

Reserve Account

Deposit in the name of a financial institution held at a Federal Reserve bank or other designated place.

Currency Circulation Federal Reserve banks provide the means for putting coins and paper money into or out of circulation. Each Fed bank maintains a warehouse of used and newly minted coins and paper money in its vaults (obviously with extensive security arrangements). When the public wants to carry more money in the form of coins and paper, as happens, for example, around the Christmas holidays, more checks, drafts, and such are cashed and more visits are made to ATM machines. And as financial institutions require more coins and paper money to convert their customers' deposits to currency, they order what they need from the Fed. When the Fed delivers cash to a financial institution, the cash is paid for out of that institution's reserve account. When less cash is wanted by the public, as happens, for example, after the Christmas holiday season, currency begins to build up at banks and other depository institutions. These institutions will return their cash to the Fed and receive credit in their reserve accounts. Also, when currency is worn out, it is retired by the Fed and, in the case of paper money, destroyed.

Check and Electronic Payment Clearing The Federal Reserve banks participate in the process of check and payment clearing. Each day the Federal Reserve processes millions of checks and electronic payments as financial institutions use the Fed as a payment clearinghouse. In short, the Fed participates in sorting checks and payments from deposits in financial institutions to be returned to the financial institution from which the deposit or check originated. For example, when you pay your tuition at your college with a check from your bank account, the Fed provides or oversees the means for transferring funds to your college from your bank.

When payment clearing is done within the same Federal Reserve district, the procedure is simple. However, if a check is drawn on an institution in another Federal Reserve district, it is forwarded to that district for further processing, or adds another step to the payments clearing mechanism.

Regardless of whether someone who has an account at a bank uses direct deposits, paper checks, or online banking, deposit and payment clearing causes a financial institution's reserve account to fluctuate. When a deposit is made at a financial institution and sent to the Fed for clearing, the full amount of that deposit is credited (added) to that institution's reserve account. When a check or other payment method is used by a customer with an account at a financial institution and that payment goes through the Fed clearing procedure, the full amount of that payment is subtracted from that institution's reserve account. This process causes a financial institution's reserve account to fluctuate daily, with the size of the fluctuation depending on the value of payments deposited and spent.

It is not necessary that all payments go through the Federal Reserve banks. Other clearinghouse arrangements exist. Regardless of the clearing payments mechanism, the effect on a financial depository institution's reserve account is the same: Deposits increase a bank's reserves, and payments from an account held by a bank's customers decrease its reserves.

Figure 7.3 show how a $100 check sent from an aunt in San Francisco to a niece in Atlanta travels through the payments-clearing system. When the niece deposits the check, it increases deposits in her bank by $100. When the check is sent by the niece's bank to the Atlanta Federal Reserve bank for clearing, her bank receives $100 in reserves. From Atlanta the check goes to the San Francisco Federal Reserve bank, where the aunt's bank loses $100 in reserves. Finally, the check goes to the aunt's bank, which lowers the balance in her account by $100.

Technology has created many changes in the payments clearing process. Check 21 went into law at the end of 2004 and legalizes an electronic picture of a check, allowing banks to use this picture in place of the canceled check. The process described in Figure 7.3 is the same but the electronic picture, rather than the actual check, allows for a quicker movement through the payments clearing process and eliminates shipping checks. In addition, the growth of the Automated Clearing House (ACH) Network has facilitated electronic payments.

Check 21

Law that allows electronic substitute checks for checkclearing purposes.

Automated Clearing House (ACH) Network

A large electronic payments network that facilitates a reliable, secure, and efficient payments system.

FIGURE 7.3 Check Clearing through the Federal Reserve System

Depository institution reserve accounts increase or decrease as checks move through the Federal Reserve's clearing system.

Fiscal Agents for the U.S. Government The Federal Reserve banks act as fiscal agents for the U.S. government by performing a variety of chores, such as servicing the checking accounts of the federal government and handling many of the tasks associated with the maintenance of Treasury securities, or the national debt.

Many of the functions performed by the Federal Reserve banks are necessary for the smooth operation of the banking system. However, sometimes commercial banks depend on each other instead of the Fed for these operational tasks. In this case, banks set up a relationship called correspondent banking. Typically, in this arrangement a smaller bank keeps some deposits with a larger bank and receives advice and various services in return.

Correspondent Banking

Interbank relationship involving deposits and various services.

Be sure at this point that you understand how a reserve account is changed, especially by check clearing. This understanding is key to the material in Chapter 8. You can use the Test Your Understanding, “Changes in a Bank's Reserve Account,” questions at the end of this chapter, and exercises in your Study Guide to explore some of the ways a bank's reserve account changes and to calculate reserve positions.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

CHANGES IN A BANK'S RESERVE ACCOUNTa

CHANGES IN A BANK'S RESERVE ACCOUNTa

- The First National Bank of Latrobe starts its day with $18,993,560 in its reserve account. During the day $1,256,780 in checks are deposited and cleared, and $1,379,000 in checks written by the bank's customers are cleared. How much is in First National's reserve account at the end of the day?___________

- California One begins its day with $35,664,440 in its reserve account at the Fed. During the day it returns $2,350,000 to the Fed in currency that has accumulated in its vaults. What is the bank's reserve account balance after the cash is returned?___________

- The MBMB Bank of El Campo has $12,450,221 in its reserve account at the beginning of the day. During the day, $644,970 in deposited checks and $788,450 in checks written by MBMB's customers are cleared. In addition, $350,000 in currency is delivered to the bank by the Fed. What is the bank's reserve account balance at the end of the day?___________

- Westmoreland Bank ends a Wednesday with $14,544,500 in its reserve account. On Thursday its customers deposit $345,660 in checks, and on Friday they deposit $467,845 in checks, both clearing on the day deposited. On Thursday and Friday, $266,890 and $351,115, respectively, in checks written by the bank's customers are cleared. In addition, the Fed picks up $100,000 in currency on Friday from Westmoreland to return to the Fed's vaults. How much does Westmoreland Bank have in its reserve account at the end of business on Friday?___________

a All depository institutions in this exercise are hypothetical.

Answers can be found at the back of the book.

RECENT TRENDS IN FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Since the early 1980s, after decades of traditional banking practices and strict government regulatory control over the banking system, U.S. financial institutions have changed significantly, especially over the last decade. We have seen increased similarities in the roles of financial institutions, consolidations and mergers that have created very large organizations, banks and other financial depository institutions move into new nonbank industries, and movement away from savings banks. More recently, we have been through a serious financial crisis, one of the most severe the United States has faced.

Legislative Changes

In 1980, one of the most significant laws pertaining to money and banking was passed: the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act. This law made financial depository institutions more similar in the deposit accounts they offer and the types of loans they make and eliminated much of the distinction between commercial banks and other financial depository institutions, such as savings and loans and credit unions. The Monetary Control Act also increased the authority of the Federal Reserve and added a new relationship between the Federal Reserve and nonmember depository institutions. In 1982 further legislation strengthened this trend.

Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980)

Legislation that increased the similarity among many financial institutions and increased the control of the Federal Reserve system.

In 1994 the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act was passed. This act opened the door for widespread interstate banking, or the ability for banking organizations to operate in more than one state. Today, we are used to large nationwide banks and likely don't remember that prior to the late 1970s, most banks were limited to operating facilities within a single state.

Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act (1994)

Allows banking organizations from one state to open or acquire banks, and to open branches, in other states.

Interstate Banking

The performance of services in more than one state by a single banking organization.

In 1999, significant new federal legislation that opened the door to the creation of huge financial institutions was passed: the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. This act tore down the strong firewall between commercial banking and other financial industries built in 1933 with the Glass-Steagall Act. Glass-Steagall had set an environment for control over banking by keeping banking apart from securities, insurance, and other financial industries. This separation would no longer hold.

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

Passed in 1999 to allow bank holding companies to become financial holding companies and engage in securities and insurance activities.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act influenced the activities of some holding companies, which are corporations formed for the purpose of owning, or holding, the controlling shares of stock in other corporations. Bank holding companies were permitted to become financial holding companies, and financial holding companies were now permitted to engage in a wide range of bank and nonbank activities. More specifically, these financial holding companies could now own corporations that engage in securities underwriting and dealing, and insurance agency and underwriting activities, as well as banking activities. Under Gramm-Leach-Bliley, the Federal Reserve was designated as the “umbrella” supervisor of the financial holding companies. Simply, a bank holding company could now add to its operation a variety of other types of corporations that it was not previously permitted to own.9

Holding Company

A corporation formed for the purpose of owning, or holding, the controlling shares of stock in other corporations.

Financial Holding Company

A holding company that can own the controlling shares of stock of corporations in banking, securities, insurance, and other financial activities.

In October 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act was passed in the middle of what we now label as “the financial crisis of 2007–2009.” The Act's purpose was to stem the possible collapse of a large number of banks and financial holding companies that began to fail. Housing was affected with rising numbers of foreclosures, credit was drying up, and there was much uncertainty over the future of the financial markets. This Act gave the U.S. Treasury about $350 billion initially, with another $350 billion later. This action by Congress brought controversy over the size of the bailout, continued exorbitant salaries to executives, and a lack of accountability.10

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act

Passed in 2008 to provide $700 billion to the U.S. Treasury for assistance in keeping financial companies from failing.

In July 2010, one of the most extensive acts regulating financial activities was passed: the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, known simply as Dodd-Frank. This Act followed the financial crisis of 2007-2009 and has been extremely controversial: Some critics say it is too limited in its oversight and others say it overly regulates the financial sector. Dodd-Frank was mentioned frequently during the political campaigns of 2012 as candidates took positions about enforcing or repealing it.

Dodd-Frank

Legislation passed in 2010 to increase accountability in and regulation over financial institutions and the instruments and products they provide.

Dodd-Frank is hundreds of pages and broad in scope. It strengthens consumer protection with new authority, heads off financial bailouts, creates an advance warning about systemic issues that threaten the economy, regulates exotic financial instruments, enforces regulations already in existence, and gives more oversight ability to the Federal Reserve, among other regulatory reforms.

Structural Changes

All of the legislative changes in regulations concerning branch banking, interstate banking, and the ability to form financial holding companies have changed the face of banking during the past three decades. In addition, advances in technology have altered the way banks do business and made it easier to complete transactions.

The size of a banking organization is largely determined by its ability to attract deposits, which, in turn, is influenced by location. Even with the growth in technology, people still want easy access to their banks. Banks in large urban areas with facilities in multiple locations have more potential to be large than banks located in small, rural communities with a few facilities. As a result, branch banking, where a bank operates more than one facility, is a significant factor in the size of a bank. In 2011, there were about 83,000 bank branches.11

TABLE 7.5 The 10 Largest Commercial Banks

The 10 largest banks are ranked by assets.

Source: “Large Commercial Banks,” Federal Reserve Statistical Release, April 27, 2012.

Branch Banking

Operation of more than one facility by a bank to perform its functions.

With the passage of Gramm-Leach-Bliley, there has been a growth in extremely large banking organizations. Table 7.5 gives the 10 largest commercial banks as of December 31, 2011. By the time you read this text, this list will have likely changed. Notice the size of the assets of these banks: The largest bank has close to $2 trillion in assets and is about five and one-half times the size of the fifth largest bank. These banks also have rather large numbers of branches, over 6,000 in one case.

Mutual Fund Growth A factor affecting the banking system is growth of the mutual fund industry. A mutual fund is a pool of dollars from depositors that is used to make financial investments in corporate stocks or bonds, government securities, or other instruments. Mutual funds compete with financial depository institutions for household savings and time deposits, and for providing funds for business loans. In 1990, there were about $1.1 billion of assets in mutual funds, and by 2010 that amount was over $11.8 trillion.12

Mutual Fund

Pool of money from depositors that is used to make investments.

Mutual funds appeal to individual savers who want a higher return than they can get from CDs or passbook savings and who are willing to assume some degree of risk. Unlike savings and time deposits in banks, mutual funds are not insured and the return to the owners of these funds fluctuates.

Savings and Loans Before the late 1980s, saving and loan associations were a large part of the financial institutions landscape. Since that time most have been merged into other institutions or simply closed. The legislative and structural changes that altered traditional banking roles were the basis for a substantial number of savings and loan failures in the late 1980s and 1990s. Deregulation contributed to these failures as many institutions, no longer operating with interest caps, offered unprofitably high interest rates to attract deposits. Also, with new freedom to provide different types of loans, some institutions offered loans with little or no collateral and speculated on risky real estate.

The failures and insolvencies of these savings and loans caused the federal government to provide significant amounts of financial assistance in what might have been the first Congressional financial bailout. When the price tag was finally tallied, the bailout for cleaning up the insolvencies was $480.9 billion or about $2,000 for every man, woman, and child in the United States.13

The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009

This chapter is concerned with traditional banking. Traditional banks are chartered by the federal or a state government, regulated in their operations and policies by the Federal Reserve, associated with agencies like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and provide demand deposits and other checkable deposits. Traditional banking holds the key for controlling the money supply (as we will read in Chapter 8).

In recent years, there has been the development and growth of a host of financial entities we label as shadow banks. Shadow banking refers to the institutions and markets that provide many of the traditional banking functions, but exist and function outside the regulated banking system. These can range from investment banks and mortgage companies to the provision of money market mutual funds. Shadow banks provide a means for investing money through a range of different opportunities.

Shadow Banking

The institutions and markets that engage in some traditional banking functions but operate outside of the traditional banking regulations.

It is important to understand that the shadow banking sector is not subject to the oversight, control, and regulation of traditional banks. These institutions have the ability to operate in a more creative fashion than traditional banks, even crafting financial instruments that may not be subject to control. Shadow banking companies and their traders are motivated to maximize profit like other businesses. In recent years, many of these shadow banking operations have grown to huge entities with a concentration of financial assets that can have an enormous impact on the economy, especially when they fail. It is the shadow banking sector that is primarily responsible for the financial crisis of 2007–2009.

During the financial crisis of 2007–2009, some financial institutions in the traditional and shadow banking sector found themselves in trouble. Some of the large investment banks had made investments that left them vulnerable and caused them to fail, like Lehman Brothers, or to be sold at low prices, or to need government bailouts to keep them afloat.

The mortgage market provides some insight into the crisis and gives you one example of the growth and operation of shadow banking. Mortgage market bundling was just one of the many creative financial instruments that were risky and began to fail, causing panic in shadow banking organizations as the crisis developed.

During the years prior to the financial crisis, the price of housing in some markets increased rapidly and the economy was in good shape. Many mortgage companies were eager to sell mortgages and offered deals to people who should not/could not qualify for the size of the mortgage they received. These shaky mortgages were labeled as subprime mortgages. Subprimes were attractive because they carried a high interest rate for the lender and frequently had a short time frame that caused a rate redo of the mortgage in a few years. In short, the lenders of the mortgage money thought they had a good deal with the high interest rate and the borrowers were happy to get a loan, sometimes counting on the rising value of the property as an opportunity to “flip it” and make a nice profit.

Subprime Mortgages

Borrowers have lower credit ratings and a greater risk of default; interest rates tend to be higher than prime mortgages.

Many mortgage companies began to bundle their prime and subprime mortgages and sell them as packages to institutions in the shadow banking sector. In the mortgage bundle was a mix of good, well-backed mortgages but also some subprime ones. The interest rate on the subprimes made the bundle attractive.

Mortgage Bundling

Mortgages are packaged together and sold as a group; mixed mortgage bundles are a collection of prime and subprime mortgages.

APPLICATION 7.3

BEN BERNANKE'S REFLECTIONS ON THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

BEN BERNANKE'S REFLECTIONS ON THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

Mr. Bernanke's speech was given on April 13, 2012, and focuses on the causes of the 2007–2009 financial crisis. This speech pulls from talks and testimonies he gave on the crisis and provides a perspective in its aftermath.

[In analyzing the crisis, earlier testimony] drew the distinction between triggers and vulnerabilities. The triggers of the crisis were the particular events or factors that touched off the events of 2007–2009—the proximate causes, if you will. Developments in the market for subprime mortgages were a prominent example of a trigger of the crisis. In contrast, the vulnerabilities were the structural, and more fundamental, weaknesses in the financial system and in regulation and supervision that served to propagate and amplify the initial shocks. In the private sector, some key vulnerabilities included high levels of leverage; excessive dependence on unstable short-term funding; deficiencies in risk management in major financial firms; and the use of exotic and nontransparent financial instruments that obscured concentrations or risk. In the public sector, my list of vulnerabilities would include gaps in the regulatory structure that allowed systemically important firms and markets to escape comprehensive supervision; failures of supervisors to effectively apply some existing authorities; and insufficient attention to threats to the stability of the system as a whole (that is, the lack of a macroprudential focus in regulation and supervision).

[In regard to the subprime mortgage issue] judged in relation to the size of global financial markets, aggregate exposures to subprime mortgages were quite modest. By way of comparison, it is not especially uncommon for one day's paper losses in global stock markets to exceed the losses on subprime mortgages suffered during the entire crisis, without obvious ill effect on market functioning or on the economy. Thus, losses on subprime mortgages can plausibly account for the massive reaction seen during the crisis only insofar as they interacted with other factors—more fundamental vulnerabilities—that served to amplify their effects.

A number of the vulnerabilities … were associated with the increased importance of the so-called shadow banking system…. Indeed, the very foundation of shadow banking and its rapid growth before the crisis was the widely held view [that safeguards] would protect shadow banking activities against runs and panics…. When it became clear to investors that these alternative protections might not be adequate to protect against losses, widespread flight from the shadow banking system occurred, … [Other vulnerabilities can be viewed as a consequence of poor risk management by financial institutions and investors]. Unfortunately, the crisis revealed a number of significant defects in private-sector risk management and risk controls, importantly including insufficient capacity by many large firms to track firmwide risk exposures…. [that] led in turn to inadequate risk diversification, so that losses—rather than being dispersed broadly—proved in some cases to be heavily concentrated among relatively few, highly leveraged companies….

In retrospect, it is clear that the statutory framework of financial regulation in place before the crisis contained serious gaps. Critically, shadow banking activities were, for the most part, not subject to consistent and effective regulatory oversight. Much shadow banking lacked meaningful prudential regulation…. The gaps in statutory authority had the additional effect of limiting the information available to regulators and consequently, may have made it more difficult to recognize the underlying vulnerabilities and complex linkages in the overall financial system….

A broader failing was that regulatory agencies and supervisory practices were focused on the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions or markets—what we now refer to as microprudential supervision. In the United States and most other advanced economies, no governmental entity had either a mandate or sufficient authority—now often called macroprudential authority—to take actions to limit systemic risks that could result from the collective behavior of financial institutions and markets.

Source: Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, “Some Reflections on the Crisis and the Policy Response,” given at the Russell Sage Foundation and The Century Foundation Conference on “Rethinking Finance,” New York, New York, April 13, 2012. www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20120413a.htm.

When the economy began to slide in 2007 and people lost their jobs, many were unable to pay their mortgages. In addition, the price of housing declined, sometimes severely, in many markets. As a result, many shadow banking institutions were left holding a bundle of mortgages that included many that were nonperforming. In addition, the value of the property in the bundle was declining. So, now that $500,000 mortgage couldn't be paid and, worse yet, the house was worth less than $500,000. In other words, what some thought was a good deal wasn't and it left them holding a bag of declining value. This meant that a major asset of the holder was worth less and less. Now the organization faced a real issue: do we panic and try to sell these bundles at a lesser price or do we hold onto an asset that is worth much less? Each of these decisions means a decline in the value of the organization.

The mortgage situation was just one example of “what looked good on paper” having some underlying problems and issues. The underlying problems and the financial crisis were extremely complex and today we are still trying to sort it all out. Books are being written to try to analyze the situation and delve into the details of the crisis. Application 7.3, “Ben Bernanke's Reflections on the Financial Crisis,” will give you some good information to understand the causes and problems that led to this significant financial crisis. Mr. Bernanke's speech is a good perspective and is available in its entirety on the web (see footnote of the application). If you are interested in learning more about the crisis, this speech is a good starting point.

UP FOR DEBATE

SHOULD CONGRESS ENACT MORE STRINGENT REGULATIONS OVER THE BANKING SYSTEM?

SHOULD CONGRESS ENACT MORE STRINGENT REGULATIONS OVER THE BANKING SYSTEM?

From 1980 to 2010, the banking industry became more deregulated. However, the near collapse of many large banks in 2008 caused Congress to provide a $700 billion bailout for the financial services industry and brought more regulation with Dodd-Frank. But the debate over the extent of regulation needed to ensure safety and stability in banking continues. Should Congress enact more stringent regulations over the banking system?

YES The crisis of 2008 is certainly indicative of the need to return to more stringent banking regulation. From the Depression in the 1930s until more recent years, the United States enjoyed a fairly safe and secure banking industry. During that time, the banking industry was regulated in terms of the activities that banks could undertake, and their size was limited because of various regulations. Banks were more personal places for customers such as business owners, who could turn to their local banker for loans.

While banks are profit-seeking corporations and their stockholders like to see the highest dividends possible, the banking industry is unlike others. Safe and secure banking is essential to a healthy economy. Once the banking system goes, the entire economy becomes dysfunctional. This reality became quite apparent with the quick approval in Congress of a substantial bailout of the financial services industry in the fall of 2008. The collapse of these institutions would have crippled the economy.

It may not be in the best interest of consumers to continue on the road of mergers, consolidations, and adding securities and insurance services to these large banking entities. For one, bank customers may end up with fewer choices, higher prices, and less responsiveness—all results of less competition in markets. In addition, the assumption of less risk with investments because they are bought through a bank, particularly among consumers who mistakenly believe that the FDIC is ensuring these transactions, could hurt the less informed customer.

NO Returning to an era of more stringent banking regulation because of the “sins” of a few is like punishing an entire classroom of children for the actions of one. Just because a few of the financial services holding companies engaged in poor, risky business practices, this is no reason to return to the old style of banking. The action that is needed is better audits and supervision of these financial services companies.

The ability of banks to become financial holding companies has benefits for consumers. Now bank customers can take advantage of a wider array of products in one place to meet their increasingly sophisticated needs. Rather than banking at one location, investing at a second, and taking care of insurance needs at a third, customers can conduct all of these activities at the same place. In addition, with all of these new opportunities, competition in these industries should increase, giving consumers more choices and better prices and services. It also can lead to more efficient operations.

Finally, banks and financial holding companies are profit-seeking corporations that thrive when their owners, the holders of their stock, see a profit from the company's operations. If banks are reregulated, this may come at the disadvantage of their stockholders. In addition, these financial holding companies have provided good jobs with excellent salaries to a large number of people who could now become unemployed.

With all of the changes in the regulation of banking and the bailouts required to salvage many financial institutions in recent years, there remains a great deal of controversy over the extent to which the financial sector should be regulated. The passage of Dodd-Frank continues to be a major topic as some believe it is too stringent and should be repealed. Up for Debate, “Should Congress Enact More Stringent Regulations over the Banking System?,” gives some of the arguments on each side of this issue.

Summary

- Money is a medium of exchange, or something generally accepted as a means of payment for goods, services, and resources. Without money to facilitate transactions, an economy would need to rely on a barter system. Money also serves as a measure of value and as a method for storing wealth and delaying payment. The value of money is measured by the goods, services, and resources it can purchase. Inflation causes the value of money to fall.

- There are two definitions of the U.S. money supply. M1, the narrower definition, includes coins and paper money in circulation, nonbank-issued traveler's checks, demand deposits (checking accounts) at commercial banks, and other checkable deposits. The other definition, M2, is important because it includes M1 plus accounts that have limited checkable features and accounts that are easily convertible to cash.

- In any year, the economy's money supply is smaller than the value of goods and services produced, or GDP. The velocity of money measures the average annual turnover of the money supply in relation to GDP.

- When money is backed by something tangible, such as gold or silver, the economy is on a commodity standard. At one time, U.S. money was backed by gold. Today, the United States is on a paper standard, where money is generally backed by people's willingness to accept it and by the strength of the economy. A paper standard has both advantages and disadvantages.

- Financial depository institutions, such as commercial banks, savings associations, and credit unions, play a critical role in the economy because they can create and destroy money through their loan-making activities. Commercial banks are the most important of these financial institutions. Agencies, such as federal and state banking authorities, the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, regulate commercial banks.

- The Federal Reserve system coordinates commercial banking operations, regulates other financial depository institutions, and oversees the U.S. money supply. The system, which is organized geographically into 12 districts, is headed by the Board of Governors. The 12 Federal Reserve banks and their branches provide services to financial institutions rather than directly to the general public. The functions of the Federal Reserve banks include supervising and examining the operations of member banks in their districts, maintaining reserve accounts, circulating coins and paper money, clearing checks and some electronic payments, and acting as fiscal agents for the federal government.

- Significant changes have occurred in the U.S. banking system since the Monetary Control Act of 1980 made financial depository institutions more similar. In 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act permitted the formation of bank and financial holding companies that allow banking organizations to conduct securities and insurance activities. Deregulation was reversed in 2010 with the Dodd-Frank Act.

- Other significant banking changes include the financial bailout through the Emergency Stabilization Act, the increase in popularity of mutual funds, the elimination of most savings and loan associations, and the recent financial crisis of 2007–2009.

Key Terms and Concepts

Money

Medium of exchange

Value of money

Barter system

Measure of value

Functions of money

Method for storing wealth and delaying payments

Definitions of the money supply

M1

Token money

Federal Reserve Notes

Currency

Demand deposits

Other checkable deposits

Velocity of money

M2

Liquidity

Commodity monetary standard

Paper monetary standard

Financial depository institution

Commercial bank

Dual banking system

National bank

State bank

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)

Asset

Liability

Net worth

Federal Reserve system

Board of Governors

Federal Reserve banks

Organization of the Federal Reserve system

Reserve account

Check 21

Correspondent banking

Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980)

Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act (1994)

Interstate banking

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

Holding company

Financial holding company

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act

Dodd-Frank

Branch banking

Mutual fund

Shadow banking

Subprime mortgages

Mortgage bundling

Review Questions

- List the basic functions of money and explain how a $20 bill fulfills each of these functions.

- How much is a $20 bill worth? How is its value measured and what causes that value to change?

- What are the basic components of M1 and M2? How do these two measures differ? In your opinion, which is a better measure of the money supply? Why?

- Answer the following questions concerning financial depository institutions.

- What distinguishes commercial banks from other financial depository institutions? Why are commercial banks so important?