The Nightmare Begins

They were humans once, these beasts that populate the cinema screen, the modern novel, and the occasional nightmare. They lived, they laughed, they loved, they died—then a legendary plot twist came along: they didn’t stay in the grave. They came back with a hunger and a vengeance.

They became zombies.

Risen from cemeteries and tombs, these are the walking dead.

If this mythic monster keeps you awake at night, it’s probably because it contains slivers of all the scariest legends. The zombie has been pieced together, a la Frankenstein’s monster, over thousands of years. Swathed in tattered burial clothes, the zombie embodies our collective memories of ancestral worship and our fear of death. It has walked through the fog-shrouded history of England, Germany, Romania, Iceland, Brazil, Haiti, West Africa, and the United States before reaching the cinematic screen in George Romero’s 1968 film, Night of the Living Dead. You might think these creatures first launched into the public arena in the 1932 movie, White Zombie, starring Béla Lugosi, or the 1936 film, Revolt of the Zombies. But in truth, the macabre roots of the zombie legend began long, long ago, in an age when all our stories were told in whispers, when men and women crouched in fear of the capricious gods they worshipped.

Back to the Past

The zombie legend began with legendary beings: the gods of ancient Greece, Egypt, and Sumeria. In the ancient world, it was believed that only a god could travel the distance from death to life. Like forbidden fruit, this was not the stuff of mortals. In Greek legends, love drove Orpheus on his journey to the underworld, where he tried to rescue his dead wife, Eurydice. He almost succeeded in bringing her back but failed by disobeying Hades’ orders and glancing back at his wife before she crossed into the upper world. A somewhat similar Egyptian love-story-wrapped-in-myth tells of the god Osiris, murdered by his brother Set, then magically resurrected by his sister and wife, Isis. As time passed and this story was retold, it metamorphosed, first granting immortality to Egyptian kings, and then later, in the New Kingdom era (16th century B.C. to the 11th century B.C.) to all people who knew and performed the proper rituals.

This is the twisted path legends often take, changing slightly with each retelling.

As time passed, stories began to spread throughout the world about others who had returned from the dead. From the Sumerian tales of the god/king Tammuz rescued from the underworld by Inanna to the Hebrew Old Testament stories of Elijah and Elisha raising children from the dead to the Celtic ceremonial slaying of an aging king in the belief that his spirit would then inhabit a younger king, death was now seen as a door that could swing both ways.

Unfortunately, once it began to swing open, what walked through wasn’t always friendly.

Common Ancestors

Today, those of us living in the Western world view ghosts as insubstantial and without substance. But this wasn’t always the case. This particular viewpoint of spirits didn’t become popular until the Victorian era. Before that, the returning dead were believed to be corporeal creatures with the ability to do harm or good—although they seemed to opt for harm more often.

In Romania, these creatures were called moroi (benevolent spirits), or strigoi (malevolent spirits). When believed to be departed family members, these emissaries of the returning dead were often invited into homes and given a meal. This particular wraith is a common ancestor to both vampires and zombies. In Iceland, the Vikings believed in draugars, corpse-white or coal-black creatures who returned from the grave with malicious intent. Many of the Sagas of Icelanders from the 9th to the 14th centuries A.D., like the Laxdoela and the Eyrbyggja and the Grettis, include tales of dead men coming back for vengeance or sport. It was believed that the draugar could eat the flesh and drink the blood of their victims.

During the 12th to the 15th century, both England and Germany joined in on the telling of tales, with medieval ghost stories written by monks, courtiers, and churchmen. English writers included William of Newburgh (1136-1198), a Yorkshire canon who wrote that ghosts attacked people and drank their blood, and the 14th-century monk of Byland Abbey who wrote of James Tankerlay, an infamous ghost who returned from the grave to attack his former concubine. Walter Map (1140-1210), courtier of King Henry II of England, wrote some of the earliest vampire stories, while his contemporary, William of Newburgh (1136-1198) wrote of medieval revenants, corpses that returned from the grave.

At this point, the door to the world of the dead no longer swung open on occasion. It had been left ajar. These ghosts and spirits of written folklore had physical bodies—they could eat meals, drink alcohol, and get in fights with humans. Like disobedient children, they refused to stay in the tomb at night, preferring to carouse and stir up trouble. Consequently, their rotting bodies were often exhumed, then burned, staked, or chopped in bits, sometimes replete with a ceremonial beheading, similar to what we associate with vampires today.

By the 1800s, another phenomenon began to stir the imagination and, subsequently, found its way into the pages of literature: Catalepsy, a physical condition that produces muscular rigidity and an appearance similar to death. Today, doctors believe catalepsy is associated with catatonic schizophrenia. Unfortunately, this condition went undiagnosed and untreated in the 19th century and because of it many sufferers went to an early grave—while still alive. Tormented by this fear, Edgar Allan Poe wrote The Premature Burial and The Fall of the House of Usher. This affliction also found its way into stories by Alexandre Dumas: The Count of Monte Cristo; Arthur Conan Doyle: The Adventure of the Resident Patient; and George Elliot: Silas Marner.

Real tales of catalepsy circulated as well.

In the late 1800s, a woman named Constance Whitney perished, or so it seemed. While still in her coffin, a sexton tried to pry off one of her rings. He accidentally cut her finger with a blade. At this point, she woke up, gave an audible sigh, and then went on to live for several years. A similar tale arises from Northern Ireland, where the body of a wealthy woman was exhumed by thieves. While attempting to steal one of her rings, the “dead” woman revived.

The terms “undead” and “back from the dead” began to take on new meanings. The line between life and death was blurring, setting the stage for the final act in this monster’s journey.

Voodoo

In the late 18th century, a Haitian slave uprising and a spirit-based belief system known as voodoo worked together to create an atmosphere of danger and dark magic—the perfect ingredients for the zombie myth to flourish. This belief system traveled from the tribal villages of Africa to the sugarcane plantations of the Caribbean, assimilating many Catholic customs along the way. It took root in Haiti (then known as Saint-Domingue), an island where the slaves soon outnumbered their owners by 10 to 1. Ultimately, voodoo became a political device with “priests”—or houngan—urging their followers to war against their owners. For some time, the Caribbean plantation owners worried that their slaves might rebel—a fear that manifested itself in Haiti in 1791. In this uprising, two different island voodoo traditions, Petro and Rada, joined forces, targeting the petit blancs and the plantation owners. These uprisings continued until 1804, when Haiti became an independent republic.

Fear played a large part in the 13-year revolution, and as a result, zombie myths began to circulate throughout the Caribbean and France. Outrageous stories were told about how the local Haitian houngan employed dark magic to raise the dead, thus creating their own soldiers to war against the militia. Rumors of cannibalism spread as well. Initially, these rumors were created to cause animosity toward the local Creoles and to help quell the rebellion.

Oddly enough, these rumors were the labor pangs that would give birth to the monster that now lumbers across our modern cinema.

The Zombie Slave

Voodoo legends continued into the 19th century, claiming that either a bokor, a houngan, or a mambo could raise the dead and make them do their bidding. Since that time, stories have been told of mindless victims found years after their supposed deaths, stories like the Haitian tale, later proven false, of Felicia Felix-Mentor, allegedly found wandering about in a trance-like state 30 years after her burial. Or the tale of Clairvius Narcisse, who supposedly died in Deschapelles, Haiti, on May 2, 1962, and was later found, alive, in a village in 1980. Narcisse claimed that a bokor had given him a poudre. After this, doctors declared him dead, Narcisse was buried, and later “resurrected.” Drugs given to him on a regular basis had allegedly numbed his senses and turned him into a zombie, after which he was sold as a slave to work on a sugarcane plantation.

Hoping to discover a new medicine, Dr. Wade Davis spent years investigating the various zombie powders used by bokors, then recorded his findings in The Serpent and the Rainbow and The Passage of Darkness. Davis concluded that a drug, or several drugs combined, had caused Narcisse’s condition. His theory, based on samples collected while in Haiti, stated that bokors combined tetrodotoxin (from puffer fish), toxins from marine toads, various lizards and spiders, human remains, and sometimes even ground glass to create the powder used in their rituals. Despite Davis’ research, the drug used to turn Narcisse into a zombie was never scientifically documented or proven.

Nonetheless, by this time, zombies had already achieved a level of notoriety, becoming the monster muse for both screenwriters and novelists. In 1929, W.B. Seabrook led the pack with Magic Island, a steamy voodoo tale set in turn-of-the-century Haiti. A flurry of movies followed that captured the essence of the voodoo zombie slave: White Zombie in 1932; Ouanga in 1936; Revolt of the Zombies in 1936; and I Walked with a Zombie in 1943. Then the mood changed in 1968 with the cult classic film, Night of the Living Dead, when George Romero introduced new elements: cannibalism, science fiction, and the zombie apocalypse. Heavily influenced by I Am Legend, the 1954 vampire novel by Richard Matheson, Romero’s tale no longer relied on voodoo or sorcery to raise the dead. Likewise, today, the modern zombie often bears the scars of science gone wrong, with resurrection caused by anything from outer space radiation to toxic gas to an incurable virus to a mysterious cell phone signal. Like the birth of Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, you can almost smell the electricity crackle as new ideas emerge. The legend continues to change with each retelling, as new books and movies grant the undead zombie new abilities—now he’s agile, now he’s intelligent, now he wants equal rights.

At this point, the zombie-returned-from-the-dead can be worked into almost story or portrait. From Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice with Zombies to Max Brook’s World War Z, the grave is the limit.

It’s time to start digging.

Classic zombies walk with a shuffling gait, all limbs stiff, movement awkward, laborious and slow. The stumbling corpse out for revenge may have originated in Boris Karloff’s interpretation of another monster in the cult-favorite 1932 movie: The Mummy.

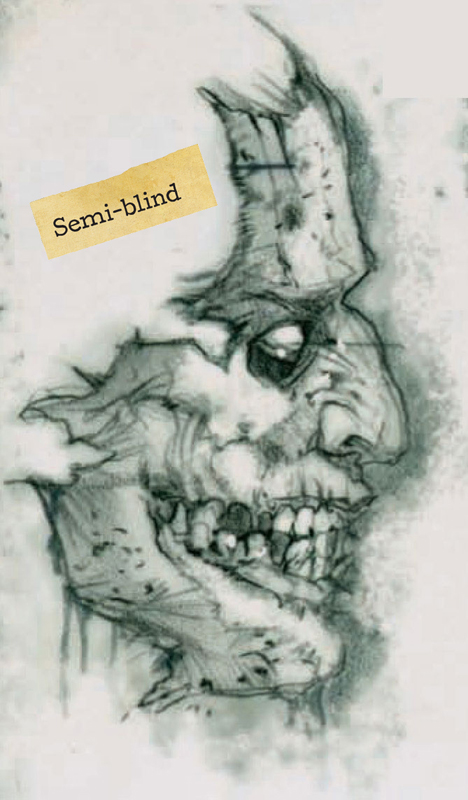

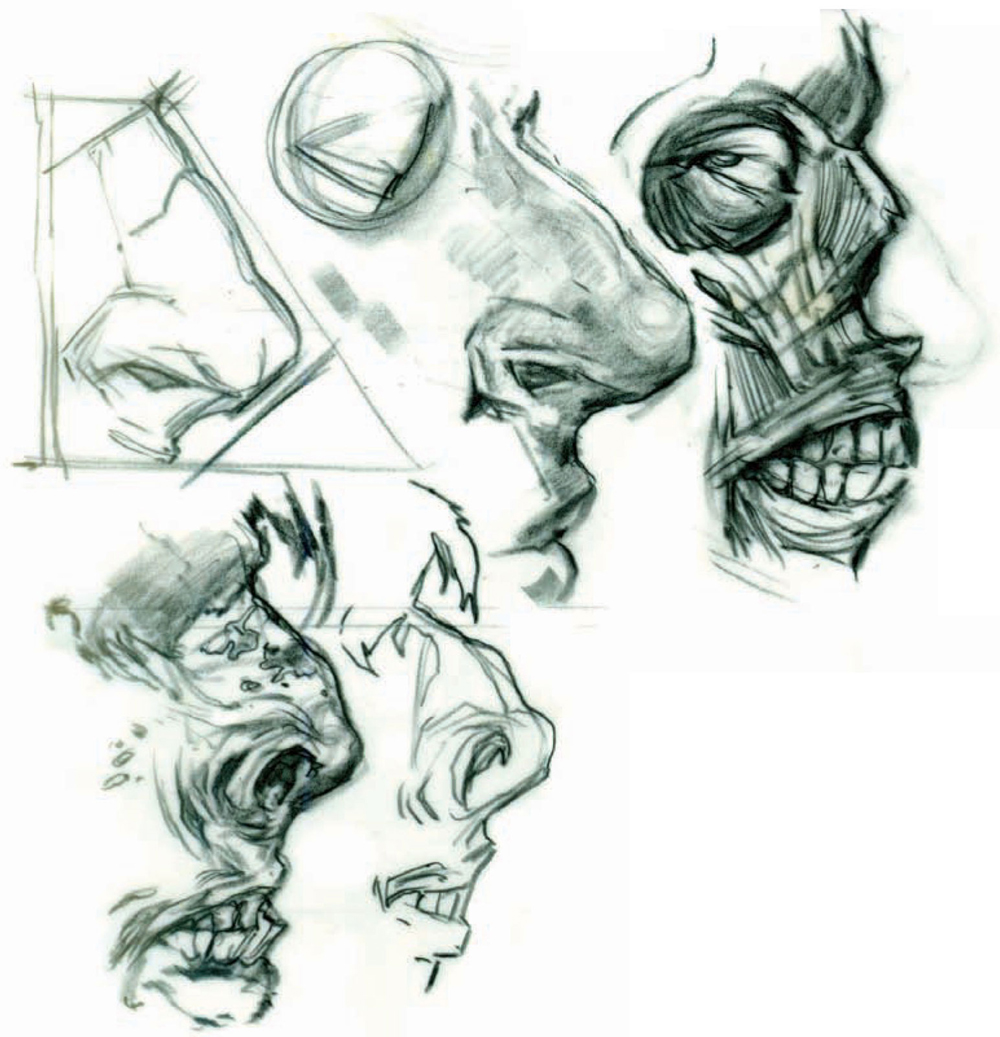

Every zombie starts as a normal human, then swiftly transforms from gorgeous to gruesome. To create your own undead monster, remember to pay close attention to the bone structure of your character. As the skin decays, all sorts of skeletal anatomy, sagging flesh, and broken bones will be exposed.

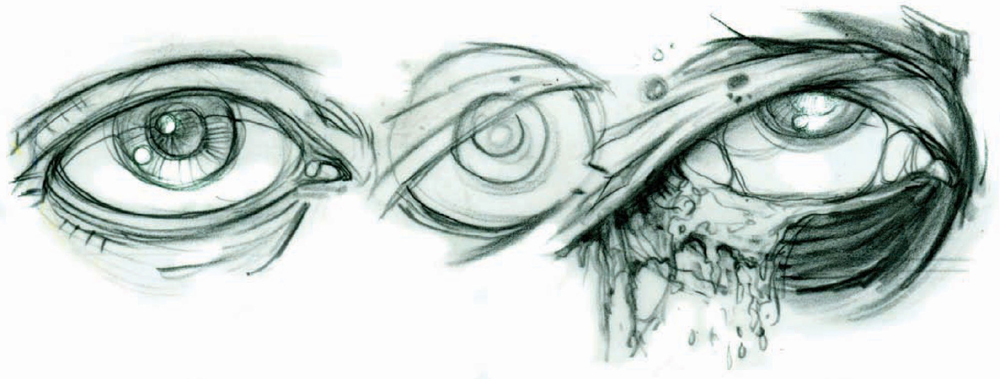

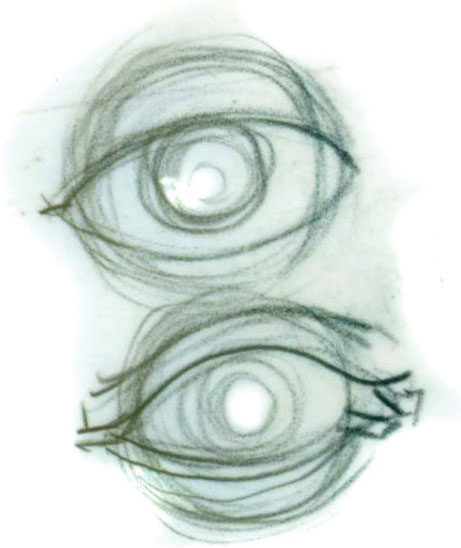

Eyes

Eyes say a lot about a person, or creature, so use this as an opportunity to express the true nature of your character. Begin by drawing a ball—this will remind you to “wrap” your lines and values around a 3-dimensional form. For an attractive human eye, the iris will remain centered in the white when it looks at you, leaving just a bit of space between it and the bottom lid.

For the zombie eye, move the iris so far up that only the bottom half shows. Then, draw in extra creases and wrinkles on the top and bottom lids, showing that the zombie has been missing his beauty sleep. Also, for a gruesome touch, you can add additional fluid and goo leaking from the inside of the eye. For a more wicked zombie, simply pull down the top lid, narrowing the inner canthus into a skinny slit.

As the flesh of the hand begins to disintegrate, you’ll find that the ligaments and bones create a network of long, thin lines. Keep the fingers curled and the tips pointed for good measure.

Nose

When drawing the zombie facial features, start with a generic drawing of a human face. For example, a normal nose has a bottom that typically runs parallel to the floor. In contrast, when drawing a zombie, give it a severe pug nose by pulling the nostrils up high and flattening the apex. For the zombie’s mouth, pull the lips back to reveal crooked and deformed teeth.

The classic zombie no longer dominates the landscape in monster lore. Today new variations continually spring up, like corroded links in an evolutionary chain gone awry. Tattered skin and exposed bone may always be in vogue, but the rest of the zombie package is open for interpretation.

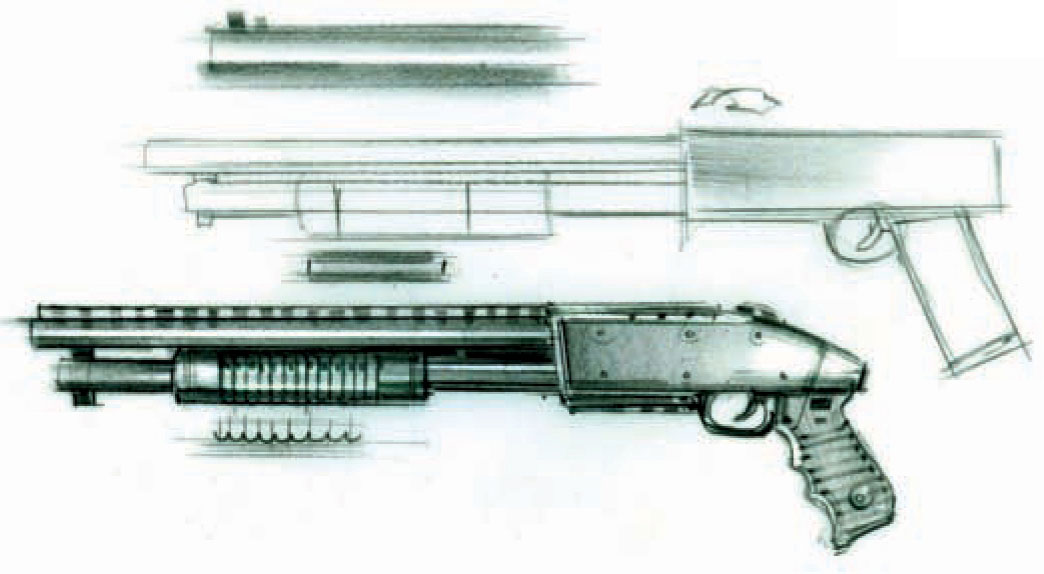

In every good zombie story, there comes a point where running away from the monster just isn’t enough. The bad guy needs to be destroyed. Unless you set him on fire, this undead creature will only return to the crypt if his head is blown off, cut off, or crushed. That means your protagonist will need an arsenal of guns, knives, or hatchets if he hopes to live.

Here we see some of the more effective weapons that have been used to dispatch the local zombie over the years. As with any drawing, start off with the simplest of shapes that represent the subject, for example, circles, cylinders, and rectangles. Keep the following three things in mind when creating believable weapons or gadgets:

• Number one: Keep the lines crisp and clean.

• Number two: Always imagine the forms are solid masses so that you can shade and add value accordingly.

• Number three: The perspective must be accurate. As long as the perspective is correct, you can exaggerate the foreshortening, making the drawing more dynamic.

Background elements play a major role in making your zombie illustration look real. Spooky details, like a menacing tree or a creepy spider, help to make your imaginary world more real. Tombstones and crypts, the resting places that all zombies have forsaken, provide visual reminders that these creatures have supernaturally risen from the grave.

Tree

Next, we’re going to create a tree that would look perfect on a zombie’s front yard. Begin with some simple linear shapes for the trunk. We’re going to draw a very human-like form, reminiscent of the trees from your childhood nightmares. Once you’re satisfied with the line drawing, add some organic curves and folds to the tree, similar to what you would find on a long robe. Leave the branches bare and keep the ends sharp, like claws. We want this tree to have a form similar to that of a headless zombie.

Spider

Incredibly easy to draw, spiders add a whimsical, yet eerie, touch to an illustration. Begin with basic shapes to put together a recognizable form of a spider. Keep the tips of their legs razor-sharp to give them a dangerous edge. Finally, add some extra hair to the legs and abdomen of these terrifying critters and you’re done.

Tombstones and Graves

Now we’ll focus on the birthplace of the zombie—the gravesite. Start off with basic block shapes. If desired, you can do a little research on old tombstones first. When drawing, make sure your lines are clean and the perspective is accurate. Add some different textures like cracks and smudges to create a grittier, dirtier feel. You can also put sandpaper beneath the drawing when you do the shading to add to the texture.