THIS CHAPTER PROVIDES the information you need to become an educated bond buyer. Although it may be tempting to skip this material and flip to the chapter on buying bonds, consider this: it will be much harder to profit from the money-making strategies we outline if you don't understand bond basics. Read this chapter to get an overview and refer back to it when you need a refresher to help you understand a particular investment. When we first identify a word or term, we highlight it in boldface to make it easier for you to relocate it.

To induce you to read further, remember that bond returns can be quite lucrative. Consider that when stocks collectively took a hit during the market downturn that began in March 2000 and continued into 2002, the 10-year Treasury bond gained 22 percent in value between May 15 and November 7, 2001.[46] At the same time, tax-exempt municipal bonds provided yields of 5 percent for bonds maturing between fifteen and nineteen years, and 30-year Treasuries were yielding 5.35 percent. That 5 percent return on municipal bonds is a taxable equivalent yield of better than 7.7 percent for someone in the highest tax bracket, a return that comes with little risk. Trust us. The more you know about bonds, the better off you'll be.

Let's start at the beginning. Every bond has two components: (1) a time span and (2) a face value. The face value is the term used to describe the amount of money or principal you will receive at the end of the specified time span when the bond comes due.

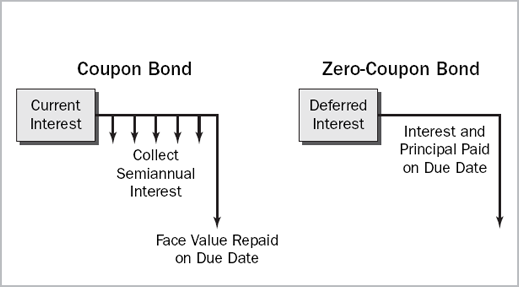

There are two basic ways to earn income from this arrangement (see Figure 5.1). In the first, you receive regular interest payments over the life of the bond. As briefly noted in chapter 4, people who received such income were once known as coupon clippers. That's because interest payments were printed on coupons that were attached to the bond. When they clipped the coupon and turned it in, they received their payment. The practice was gradually replaced by automatic, direct payment and it officially ended in July 1983, when municipal bond issuers finally did away with the paper coupons.

In today's more technologically sophisticated society, interest payments are automatically sent to whatever address you designate—be it a brokerage account or your home—and there is no need to physically present a coupon to the bank teller to get your income. However, the idea of a coupon lingers in bond terminology because a bond's interest rate is referred to as its coupon rate, or just plain coupon. The coupon rate is set as a percentage of the face value when the bond is issued. Thus, a $10,000 10-year bond with a coupon rate of 5 percent will annually pay $500, which is 5 percent of $10,000.

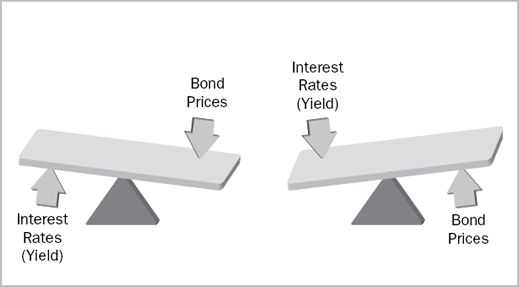

The second way of earning bond income involves buying a bond at less than, or at a discount to, its face value. For example, you may pay only $5,000 for a $10,000 10-year bond. This does not necessarily mean that you are getting a bargain. Sometimes the discount is deliberate and includes no interest payments whatsoever. This kind of bond is called a zero-coupon bond (which makes sense, because it has no coupons). The difference between your purchase price and the face value represents the income you receive. At other times, the discount reflects the fact that the bond is out of favor, and investors believe it's not worthwhile to hold the instrument until they can redeem it at full value, or they just might need the cash and must sell into an unfavorable market. As we see in Figure 5.2, if interest rates rise, the yield offered increases and bond prices fall. When interest rates fall, the yield offered on a bond is less and the price of purchase is higher.

For the buy-and-hold investor, these two basic bond structures provide financial peace of mind because they will either enjoy a steady stream of income until—or receive a lump sum at—the time the face value of the bond is returned to them. This is called redemption at maturity. People can also receive a mix of money now and money later. In other words, you buy a bond, get regular income over a period of time, a lump sum all at once, or some mix of the two, and then get all your money back when the bond comes due. For this reason, countless investors, particularly those who seek to triple and quadruple their money by speculating in the exciting stratospheres of high-risk stocks, frequently regard bonds as stodgy investments. In times when the price of those stocks sink out of sight, the so-called stodginess of bonds becomes a little less problematic.

Bonds are neither simple nor stodgy. They are, rather, very rewarding. In contrast to stocks, which represent part ownership of a company, bonds are debt—pure but not always simple. As described in chapter 4, companies, municipalities, states, and the federal government issue bonds for either short-term or long-term funding needs.

Let's look at the roles of various individuals and entities in creating and bringing a bond to market and how they shape its ultimate form. At the very beginning of the bond-issuance process, a financial adviser is called in. The adviser is a consultant who helps the issuer decide if bond debt is the best and most appropriate means of raising money for a project or need. The federal government and its agencies have internal financial advisers that perform these services. Corporations often rely on their investment banks to act as financial advisers. With regard to municipal bonds, an outside consultant frequently works with the municipality's finance director and lawyers to organize, collect, and represent the financial data to prospective buyers of the debt, including the underwriters. Most municipalities come to market infrequently and do not have an in-house staff.

After the need for bond debt has been established and a preliminary draft completed, a bond counsel reviews the contract, called the bond indenture, and gives a legal opinion that the debt is being appropriately issued. In the early twentieth century, many bonds did not have legal opinions. As investors discovered that bonds with legal opinions were less likely to default, they began to demand opinions on all issues. Bond counsel also determines where in the receiving line the bondholders stand when cash is distributed in troubled times. With regard to tax-free municipal bonds, bond counsel provides a legal opinion certifying that the bonds are, in fact, tax-exempt for federal income tax purposes.

Next, underwriters appear on the scene. They are necessary because bonds are generally not bought directly from the issuing entity. (Those issued by the U.S. government, as described in chapters 6 and 7, are conspicuous exceptions to this practice.) An underwriter is the bank or brokerage house that initially buys the bonds from the issuer and then resells them to investors. Since buying a large block of debt and then reselling it into a constantly shifting market can be financially hazardous, underwriters spread their risk by having similar organizations join in the sale of the bond to investors. The resulting grouping is called an underwriting syndicate.

Lawyers are crucial to the process of creating and issuing bonds. They next appear in the form of underwriters' counsel. In this position, they represent the brokerage house that will buy the bonds from the issuer. In today's marketplace, issuers may bypass the underwriter and sell the issue for the highest price to brokers, pension funds, bond funds, banks, hedge funds, or insurance companies.

At some point in this process, the issuer decides whether or not the bond will be callable. A call is a kind of option that gives an issuer the right, but not the obligation, to redeem a bond issue before its maturity (due date). Many bond issues have a fixed call prior to maturity. Municipal bonds may also have extraordinary calls that certain situations trigger. Bonds are called when it is advantageous to the issuer, leaving the buyer to scratch around to find another bond investment, often at a lower yield. If the possibility of an early redemption (call) worries you, the most desirable bonds for you would provide at least ten years of call protection. Call protection is always desirable for you since the ability to call a bond is always in the interest of the issuer.

In the event of a bankruptcy, not all of an issuer's bondholders are treated equally. Some bonds have senior liens, meaning that they come first in line before other creditors if there is a financial problem. Other bond issues from the same company may have only subordinated or junior lien positions.

When a single issue consists of bonds with different redemption dates, the bonds are called serial bonds. These types of bonds give the issuer the flexibility of not having to pay off everything in one lump sum. Many municipal bond issues are commonly offered this way. A term bond is a longer-term bond with a final maturity date. Many corporate and U.S. government bonds are issued this way.

Once the issuer assembles all the necessary information, writers specializing in obscure prose prepare an offering statement (OS), or prospectus. As a friend of ours once described it, only half facetiously, "[The offering statement] is written about matters that few understand and for people who will never read it." This document, produced under the issuer's aegis, sums up all the work of the professionals who created the bond and details its type, structure, special features (if any), and the strength and weaknesses of the issuer. It also describes any liabilities that might exist and the participants in the deal. If you take time to peruse it, you will learn a great deal.

It appears that the municipalities and corporations that produce offering statements feel they are not necessary to read prior to purchase since sometimes the OS is sent only after the buyer purchases a new issue bond. This situation is changing, however, since Web sites such as www.emuni.com, www.directnotes.com, and www.internotes.com post offering statements in advance of new bond issues. Individual issuers, such as the state of Utah, at www.finance.state.ut.us, are also posting prospectuses on their Web sites. We hope this trend will continue.

Having been primed and primped through many legal hands, the now dressed-up bond is ready to meet the rating analysts. These are the people who evaluate the risk of bonds as evidenced by the probability of buyers being repaid their principal and interest in a timely manner. As described in chapter 4, rating agencies came into being as a service to describe risks associated with a bond. Because there is a chance that an investor could suffer substantial losses if a bond defaults, bond issuers have to pay more to induce buyers to assume any extra risk.

Credit analysts do ratings work for bond insurers, underwriters and other large institutions, and rating agencies. Each organization relies on its analysts to review a bond's structure and its issuer's financial strength. Rating agency analysts are best known because their ratings are widely publicized and provide a recognized guide to bond purchasers. With this recognition, these analysts have become powerful players in the bond markets because their ratings strongly influence how much an issuer will have to pay to borrow money. If a bond, for example, receives the highest rating, it has almost no risk of default. Thus, under similar time spans, an issuer with a bond boasting the highest AAA rating might have to pay only 60 percent of the interest offered by an issuer with a bond rated double-B. All things being equal, bonds of the same rating and maturity are sold with similar yields if sold at the same time. When there are sharp yield disparities among similarly rated bonds, you should investigate why this is so before you invest.

Rating agencies may place bonds on credit watch if the financial condition of the issuer deteriorates. Usually the adjustments in ratings are minor. Downgrades that bring a bond rating below the investment grade of triple-B are more serious. Some institutions holding those bonds may be forced to sell them, depending on the covenants under which they operate, resulting in a general decline in the bond's price and value. Alternatively, going from double-B to triple-B can result in a nice pop-up in price.

When the changes in a bond rating are gradual and the issuer comes to market frequently, the ratings are more apt to be up to date and accurate than when an issuer only infrequently comes to market. When you purchase bonds that are not newly issued, the rating attached to the bond might not be current and in that sense is less reliable.

Rating agencies are in a delicate position because they are paid by issuers to rate their bonds. Such a situation may imply that an agency would give the most positive possible rating. On the other hand, if the public does not trust an agency's judgment, the value of its rating is useless and issuers will no longer hire the firm. Rating agencies protect their reputations by continually pointing out that their ratings are not meant to advise you to buy or sell. They also monitor the performance of their major clients, those whose bonds are actively traded in the market, and, often without being specifically paid to do so, will either downgrade or upgrade the debt of an issuer when financial conditions markedly change. This type of unsolicited rating also may occur on occasion when an issuer elects not to request a rating from one agency because they expect a different agency might be more generous.

As evident in precipitous defaults, such as Kmart, the rating agencies often play catch-up. Conseco, Xerox, and the Finova Group are other formerly blue-chip companies that have watched the sun quickly set on their company's prospects.[47] Rating agencies constantly ponder how they can provide better public notice without pulling the rug out from under an ailing company. "How volatile does the marketplace want ratings to be?" they ask. Market sentiment always precedes any downgrade. Thus, ratings are broadly viewed as lagging indicators, especially in the high-yield market.

With regard to the publicity surrounding the bankruptcy of Enron, rating agencies are not responsible for uncovering fraud. Although cooked books ultimately make rotten financial stews and result in precipitous downgrades, they are supposed to be part of accounting firms' oversight. Market prices may tell you what the ratings do not.

The three primary bond-rating agencies are Moody's Investors Service (Moody's), Standard & Poor's (S&P), and Fitch Ratings (Fitch). Federal regulators granted official status in 2003 to relatively small Dominion Bond Rating Service, of Canada. The first such move in decades, the recognition resulted from the fallout from massive accounting failure at Enron for which the rating agencies were allocated part of the blame. (See Figure 5.3 for rating agencies and their ratings.)

The agencies readily admit that their ratings contain subjective judgments. All of life's experiences cannot be boiled down into numbers, and the value of "hard numbers" is often questionable. This, plus the fact that the agencies also can disagree on exactly how new circumstances will affect cash flow for particular loan payments, sometimes leads to dissimilar conclusions. When agencies do not agree on a rating, the result is known as a split rating. The split rating may vary by an entire category (for example, AA to a high A) or reflect only variations within a category (for example, high A to a lower-grade A).

Although information that might affect the ratings is on the Internet, you have to search a bit to find relevant data. For example, you can obtain a free prospectus but no material event information that describes current changes for corporate issues by going to www.sec.gov/edgar/quickedgar.htm. The opposite is true with regard to municipal bonds. You can get free material event information from www.nrmsir.org or www.bloomberg.com, but you will have to pay to obtain a prospectus. The latter Web sites are two of four approved by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) as private repositories for offering statements. Since they are private, the sites look to make money from the sale of bond information.

The next step in the bond-debut process is setting the coupon rate, or the stated amount of interest. At all times, the issuer seeks to set a rate at which the largest buyers, mutual fund companies, banks, and insurance companies are eager to buy the bond.

Sometimes issuers sell zero-coupon bonds. As explained at the beginning of this chapter, these bonds do not pay current interest. However, the issuers have to determine the extent of the discount to face value at which the bond will be offered. These bonds are also called accrual bonds because the interest accumulates and is not paid out. It is deferred until the bond comes due.

Most bonds have a fixed rate. That means that the coupon rate is set at the time of issuance and will remain the same for the life of the bonds. That is why they are called fixed-income securities.

Once the bond is issued, its selling price may rise or fall, but its stream of interest payments, at the established coupon rate, continues unabated.

Other bonds are known as floaters or variable-rate bonds. As the names of these bonds indicate, their rates float, or are variable, and are reset periodically, generally in relation to some measure of current market rates on specified dates. Some of these bonds may have their interest rate fluctuation limited by a cap (maximum rate) and/or a floor (minimum rate). The floaters may move in the same direction as the rate to which they are tied (reference rate), or in the opposite direction, in which case they're called inverse-floaters.

Having been structured, described, and rated, a bond then makes its market debut, where it is bought and frequently re-sold in what is known as the over-the-counter market. There is no organized exchange where buyers and sellers meet. There is no bond ticker showing the changes in prices for bonds, except for certain Treasury issues that the entire bond industry uses as benchmarks.

In a competitive new issue, the highest bidder buys the bonds; in a negotiated issue, negotiation between the issuer and a selected brokerage syndicate may predetermine sales prices. In a competitive deal, there may be three or four underwriting syndicates competing for the bonds. The bonds are then remarketed to institutional and retail buyers at the set prices. Once the order period is over, the bonds are free to trade at market rates.

At its first appearance, a bond is said to be in the primary, or new, bond market. Within the primary market, Treasury bonds are sold by auction at announced times. Some large corporate bond issuers have so-called shelf registrations and allow brokers to sell bonds over time. In this case, the offering rate adjusts with the fluctuation of interest rates. Other corporate issuers, federal agencies, or municipal issuers arrange for the sale of their bonds all at once.

When a purchaser buys a new issue bond and it remains in a purchaser's portfolio until the day it comes due, it never reenters the marketplace. The issuer simply redeems it without cost. If, however, a purchaser resells a bond before its redemption date, the bond automatically enters the secondary, or previously owned, bond market. There, powerful forces come into play and determine what the actual yield will be.

Four key forces affecting a bond's yield are the credit quality of the issuer; market supply of the bond and similar issues; market demand; and overall economic conditions, including inflation. These forces either drive up or push down the amount of money buyers are willing to shell out to purchase a bond. They are all associated with risk, and, thus, it is important to differentiate among the kinds of risk.

There are nine types of risks commonly associated with buying and holding bonds:

Default risk. The risk that the issuer is unable to meet the interest and principal payments when due.

Market risk. The risk that interest rates will rise, reducing the value of bonds. We know for certain that interest rates fluctuate and that there are long-term trends. What we cannot predict is whether a shift in interest rates is only short-term volatility or whether it is reflective of a longer-term trend.

Liquidity risk. The risk that bonds cannot be sold quickly at an attractive price.

Early call risk. The risk that high-yielding bonds will be called away early, with the result that the proceeds may be reinvested at a lower interest rate.

Reinvestment risk. The risk that the interest payments and principal you receive may have to be reinvested at a lower rate. Only zero-coupon bonds do not have interest payment reinvestment risk.

Event risk. The uncertainty created by the unfolding of unexpected events.

Tax risk. The possibility that changes in the tax code or in an individual's tax position might adversely affect the tax advantages of bonds.

Political risk. The likelihood that an issuer will exercise its legal right to terminate appropriations for municipal issues and that changes in the law will adversely affect the credit quality of existing issues.

Inflation risk. The possibility that the fixed value might erode with an increased cost of living. In the United States, this is a long-term risk that is best judged in hindsight.

Where appropriate, we discuss the implications of these risks in this book, under each individual bond's description. When you are choosing investments, keep in mind the saying by Bob Farrell, a retired chief market analyst at Merrill Lynch: "Where money goes the quickest, the risk goes even faster."

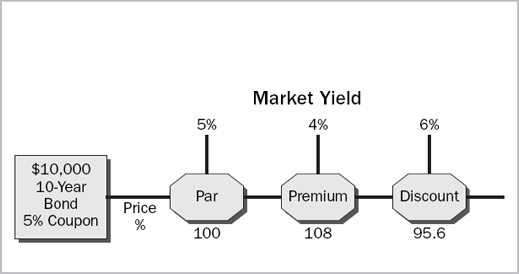

That amorphous creature called the market is at all times seeking to create equilibrium, a state in which all yields are in an approximately equal state, once risk and maturity have been factored in. Because the market cannot change the fixed-coupon rate, which is set in stone when the bond is issued, it affects the price at which the bond is sold. As the price changes, so does the yield (see Figure 5.4).

This connection between yield and price is important to grasp. For example, when a bond carries a 5 percent coupon rate and the prevailing interest rates are 4 percent, buyers will pay more than the face value of the bond to receive the benefit of a higher coupon rate. Then, the bond sells at a premium to face value. On the other hand, when that same 5 percent bond is selling at a time when prevailing interest rates are 6 percent, it can tempt buyers to purchase only at a price much lower than the bond's face value (thus, buying at a discount to face value). Occasionally, a bond will sell at its face value, and at such times it is said to be at par. Price changes reflect changes in the bond's yield. These changes can occur throughout the life of a bond, but it affects you only if you choose to purchase a bond or sell a bond you already own.

Bond costs are always quoted in "points," not in dollars. A bond selling at 101 really costs $1,010. Simply move the decimal point one place to the right to find the dollar equivalent. Thus, a par bond quoted at 100 has a face value of $1,000. To find out what your total cost would be, multiply the dollar amount by the number of bonds. Thus, 10 bonds at the 101 price would cost $1,010 × 10, or $10,100.

The concept of yield creates the equilibrium between bonds sold at different prices. This concept is so important that we highlight it here: Bonds are bought and sold based on yield, not on price. This represents a key distinction between these financial instruments and stocks, which are always bought and sold in terms of price. Yield is the general term for the percentage return on a security investment. It is often called the rate of return. In bond language, it is very different from the stated coupon rate. It is critical to understand these concepts in order to understand how bonds are valued. (See Figure 5.5.)

Keep in mind that the value of bonds declines when interest rates rise, and the value increases when interest rates decline. In short, we say that yield moves inversely to price.

Your monthly brokerage statement reflects the market valuation of your bond. It does not show concurrent changes in yield. This is called marking to market. This is of interest to you if you plan to sell your bonds. Otherwise, sit back and relax, because if we know nothing else, we know that interest rates and, therefore, the price of your bonds will fluctuate. We also know that bonds come due at their face value, and you will get your money back.

Sellers of individual bonds as well as bond funds use a variety of yield terms. Understanding them will enable you to buy bonds and invest wisely in bond funds. While many of the yields require a financial calculator to compute them accurately, the following discussion of six fundamental terms gives a general description of their use and value. Brokers will calculate bond yields for you, and funds are required to post the yields in their prospectuses. Sites that offer yield calculators include http://investinginbonds.com, www.bloomberg.com, and www.kiplinger.com.

Yield can and does mean many things to many people. Bond professionals in particular have come up with a bewildering array of meanings. Here are just a few: current yield, yield-to-maturity, yield-to-call, yield-to-worst, and yield-to-average life. Bond funds have their own terms, described in chapter 14, because bond funds do not have a fixed maturity. Each term, in its own way, seeks to create equivalency among bonds with different characteristics.

Current yield (CY) is the only simple calculation among the lot and is used for comparing cash flows.

Simply speaking, the more money you pay for a bond above its face value (par), the lower the current yield. Conversely, the bigger the discount from par, the higher the current yield. When you purchase bond mutual funds, which pay dividends, you are quoted a current yield because these securities have no maturity. The dividends from bond mutual funds are a combination of bond interest and capital gains from bond sales. Therefore, they are not directly comparable to compounding bond yields, which are quoted as a yield-to-maturity or yield-to-call.

Preferred and common stock use current yield to compare their dividends as well. However, the board of directors must approve these dividends each quarter, and there is no requirement that they pay them. By comparison, bonds must pay scheduled interest payments, or they are in default.

With the exception of current yield, all bond yield calculations take compound interest into account. Thus, this is as good a place as any to review the differences between simple and compound interest. Compound interest is called the eighth wonder of the world. It can work for you by creating wealth when you buy bonds, or it can work against you when you pay interest on your debts. It has great impartial power.

Simple interest is simple because it's calculated only on your initial investment or principal. Compound interest is complex— and rewarding—because it adds the interest to your principal and then compounds the new total; in effect, interest earns interest. Figure 5.6, which shows a $1,000 bond that pays an annual 5 percent interest once a year, illustrates the different returns from the two kinds of interest.

Compounding—interest earning interest—makes a dramatic difference over many years. Unlike bank certificates of deposit, which are sold with simple interest, bond interest is compound interest and, thus, grows at a much faster rate over the long term. The more frequently interest is compounded on the total amount, the more dramatic the difference. If you need to compare two investments, ask how much you will receive at the end of the investment. No matter what the calculation, it still boils down to your final dollars and cents.

The rule of 72. The Rule of 72 tells you approximately how many years it takes money to double when it compounds at a particular rate of annual interest. For example, if the rate of return is 10 percent, you divide 72 by 10 and learn that it takes approximately 7.2 years for the money to double at a 10 percent compounded rate. Similarly, if the rate of return were 5 percent, it would take 14.4 years to double your money (72 ÷ 5 = 14.4 years).

Yield-to-maturity (YTM) is the benchmark against which individual bonds are traded and quoted. YTM and the following two yield calculations all use the concept of compound interest. In the bond world, calculations assume that money never lies fallow or hidden away in a mattress. Rather, it is constantly reinvested to generate further income. Although YTM is not a perfect calculation, it is widely used because it is the unifying standard for all bond pricing.

YTM makes the following assumptions: (1) You retain ownership for the remaining life of the bond and (2) all interest payments are reinvested at the same prevailing rate (YTM). However, since interest rates change over time, your actual return on a bond does, too, unless you own a zero-coupon bond. If rates rise, for example, and you are able to reinvest the semiannual interest payments at a better rate, your actual return will be higher than quoted. If interest rates decline over the life of the bond, and you reinvest the interest at a lower rate, your actual return will be lower. Note that the key concept underpinning all this is compound interest. The YTM calculation assumes reinvestment of every interest payment, whether monthly or semiannually, at the YTM rate.

Whether or not you understand the dense calculations involved in determining YTM and the assumptions on which these calculations are based is irrelevant. For better or for worse, YTM is the calculation used in the bond market as the great leveler, the calculation that helps you to determine the value of one bond compared with another.

Sometimes the call date instead of the maturity date determines the bond price, and as a result the yield is calculated in terms of yield-to-call (Y TC) instead of YTM. Y TC is particularly important when interest rates have been falling because there is a good likelihood that the issuer may decide to exercise its right to call (redeem or repurchase) the bond early. This is especially likely if the coupon rate of the bond is higher than the prevailing rate of interest. If there is more than one call, the bond price is set by the yield-to-worst (Y TW), the worst possible yield you could receive for the bond as a result of an early call. Request a Y TC and a Y TW calculation from your broker because you don't know what direction interest rates will take (see Figure 5.7). The worst call yield determines the bond price just in case the bond is called. That way you are not surprised by the possibility that you will get a lower yield.

The term yield-to-average life is used in a number of different ways. It comes into play in situations in which the actual maturity is not known and is estimated instead. For example, when an individual bond has a sinking fund, a lottery determines which bonds are called, with a rising proportion of bonds called each year. It's possible that only some of your bonds will be called. Even though a bond has a call feature, it doesn't necessarily mean it will be called. Since you can't tell if your particular bonds will be called away, your broker will provide you with the yield-to-average life (also called the yield to the intermediate point), the point when half the bonds can be called away.

Municipal bonds often have sinking funds. Mortgage-backed securities also use this term. In both instances, yield-to-average life uses the anticipated compound rate of return and presumes the reinvestment of the cash flows as received. For municipal bonds, the cash flow consists of the interest payments; for the mortgage-backed securities, it includes both principal and interest.

Introduced as a concept in 1938, duration is a popular analytical tool to evaluate how much the price of a bond will increase or decrease as a result of an increase or decrease in interest rates. The duration of a bond fluctuates daily. Thus, duration serves as one measure of risk. You can use it to compare one bond to another or one bond fund to another.

In general, the longer the life of the bond, the longer its duration. The longer the duration of a bond, the greater the loss you will take if interest rates go up and you sell the bond before its due date. Similarly, the longer the duration of the bond the more of a gain you'll realize if interest rates decline and you sell the bond before its due date. If you plan to hold your bond until its due date and you actually do that, you can ignore all changes in the price of the bond because it will come due at its face value.

In general, the lower the current interest payment or coupon of the bond, the longer the duration; the higher the coupon, the shorter the duration. The duration of a zero-coupon bond is the same as its maturity. Thus, the price of zero-coupon bonds changes the most with a change in interest rates.

Let's consider a simplified example. Assume that a bond has a duration of four years, and you sell it soon after its purchase. In this case, if interest rates go up by 1 percent, the price of the bond will go down by approximately 4 percent. Similarly, if interest rates go down by 1 percent, the price of the bond will go up by approximately 4 percent.

You don't need to know how to calculate duration. You can ask your broker for this measure. Think of it as a measure to explain any interest risk. Duration is neither bad nor good. It is a measure of risk that applies if you don't hold your bond until its due date. Since bond funds never come due, it is frequently used to describe them.

Bond traders all look at their bond returns on a total-return basis. Because we recommend a buy-and-hold approach for individual investors, we are not in favor of looking at bonds in this way. In this, we're in the minority, so you ought to know what the majority is talking about. Total return takes into account both the interest you receive plus the change in value of the bond. In addition, you should take into account any transaction costs, fees, and taxes you might have to pay, which are frequently left out of the calculation.

The concept of total return is the same for individual bonds as it is for stock or any other investment. The only difference is that bonds have a better cash flow and generally less price fluctuation than most other investments. By marking to market your investments every day, brokerage houses encourage you to think about bonds in terms of total return. One outcome of total-return thinking is that you may impulsively sell your bonds when you have a gain or a loss without thinking through the advantages of the buy-and-hold strategy. Keep in mind that in showing market movements, brokers do not show the effects of the transaction costs, fees, or taxes.

Funds always use the concept of total return because funds generally don't liquidate at a defined date. Instead, they mark to market daily with the fluctuation of interest rates and the purchase or sale of bonds within the fund. The interest received as well as the capital appreciation of the bonds in the fund determine the dividends. Funds can pay out interest and capital gains monthly, and they must pay out all the interest at least annually. If there are losses, they are not passed through to the shareholder, but may be retained to offset capital gains that the fund makes from the sale of the bonds.

Figure 5.8 offers a sample of what interest payments might look like, from a portfolio of bonds that you create for yourself or one created by a bond fund. It also shows a semiannual interest payment from one individual bond.

Each bond pays interest semiannually. They are like packets of energy, usually bursting every six months. A collection of bonds, whether purchased through a fund or created on your own, pays interest spread over the year. Your cash flow from a fund might contain capital gains as well as interest so it would not flow in even amounts, though you could request an even distribution. You could sell some shares if the dividend payments from your fund were not sufficient to cover your costs. You could sell a bond, but it would be more costly. However, if you purchase bonds that mature at regular intervals, the bonds will return principal and maintain good cash flow.

To ease concern about selling bonds in the secondary market, some issuers add a put feature to their bonds to make them more attractive to individual buyers. In the event of death of the bond-holder, the estate can receive the face value of the bonds even if the bond is selling at a discount. The advantage of this feature is that you can purchase longer-dated bonds without concern for the market value of the bonds beyond the natural life of the holder. Theoretically, your bonds would become liquid upon your death.

It is important to inquire if the securities you're considering purchasing have a survivor's option. It is generally available on the following types of securities:

U.S. Agency Freddie Mac weekly notes

Certificates of deposit

Corporate note programs structured for individuals

Mortgage-backed securities structured for individuals

However, each issuer may have different restrictions. It is necessary to understand them before you purchase. For example, there may be a minimum holding period, ranging from six months to one year. The owner might be required to have lived for a defined period of time before a claim is submitted. There may be limits on the amount redeemed in any one year, or at any one time. Claims may be paid only on specified dates. There may be limitations if the account is not held in the individual's name or in a joint account with rights of survivorship.

Although there is a market for discounted bonds with this feature, it's important to consider the taxes you may have to pay on the gain between the purchase and redemption prices when calculating your yield.

When you purchase secondary market bonds, the bond may have been outstanding for some time. The bond may have little or no call protection. In this situation, the yield at the par call determines your purchase price.

Pricing becomes tricky within the secondary, or used, bond market. Corporate and agency bond pricing changes in relation to the price of Treasuries, although the actual spreads over Treasuries vary because they are based on the market's view of the particular bond being sold. This kind of spread is sometimes called a credit spread, distinguishing it from the spread that refers to the difference between the broker's buy and sell price. A broker asks a customer to buy a bond (ask price) and offers to buy bonds by placing a bid in to purchase bonds (bid price). The spread between the bid and the ask is generally tiny for Treasury bonds, while widening for less frequently traded securities. If you want to determine the spread on the bond you're considering purchasing, you can ask the broker to give you a hypothetical bid as well as his selling price. If you ask him to drop the jargon, you're less likely to be confused.

The spread is measured in basis points (bp). One basis point equals one hundredth of 1 percent (.01 percent). There are 100 basis points in 1 percent. The difference between a yield of 5 percent and 6 percent, for example, is 100 basis points. If a Treasury bond is yielding 5 percent and the spread over Treasuries was 125 basis points, the yield on a corporate bond would be 6.25 percent.

The yields on Treasury bonds are benchmarks for all bonds, although as noted above, they are particularly useful for corporate and agency securities. Treasury yields are in constant flux. The latest, most liquid 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds are the benchmarks for evaluating the interest rate payable by other bonds with similar maturities. These are called on-the-run Treasuries, compared to other off-the-run Treasuries, or those that are not actively traded.

To illustrate how spreads are used in pricing corporate bonds that are not in alignment with their ratings, we present their value quoted in basis points compared to the 10-year Treasury on February 13, 2002:

AAA-rated General Electric Corporation 7.375 percent of January 19, 2010, was priced 185 basis points to the 10-year Treasury.

A2/A1 Target Corporation, the retail department store, 6.35 percent of January 15, 2011, was only 180.

WorldCom Inc., the telecommunications company, 7.5 percent coupon due May 15, 2011, still rated A3/BBB1, was 1320.

The numbers above reflect the marketplace's estimation of risk despite the ratings. The marketplace determined that General Electric's balance sheet had too much debt despite its AAA rating, while lower-rated Target's reputation was not in jeopardy. WorldCom had already been judged risky, and the spread over Treasuries reflected that. The market's evaluation of WorldCom was prescient because the accounting scandal announced in June 2002 sent the value of WorldCom bonds to the deep sea.

Municipal traders in the secondary market use price matrixes showing ratings and due dates to determine what a bond is worth, since most muni bonds trade infrequently. Traders see where other similar bonds are trading and price the bonds accordingly. You can check for yourself at www.investinginbonds.com by inserting the CUSIP number of your bond and finding out what the trading history is. This is like pricing a used car. In an unstable market, those prices can be very misleading; however, you will have a framework for understanding what is being offered to you.

The scale for muni bonds is different from the scale for corporate bonds or Treasury bonds. Each is a separate though related market. Municipal bond prices are not adjusted as quickly as Treasuries, although they also move in relation to Treasuries. This difference exists because muni bonds serve a different market, namely, buyers interested in a tax-exempt product. Demand and supply differences skew the prices.

Why bother with the concept of basis points and yield? Why not just look at the cash you invested and the cash return you are getting on your money—so-called cash on cash? The answer is that by simply counting the actual dollars earned, you are looking at interest as a "naturally barren commodity,"[48] like an ear of corn. If you refer to Figure 5.6 comparing simple interest to compound interest, it will help you to understand why cash on cash is not sufficient. Figure 5.6 shows that if you invest $1,000 at 5 percent interest, you will have an extra $50 after one year. A yield-to-maturity calculation cannot improve on that. However, by the thirtieth year, you would have $2,500 ($1,500 of interest plus the return of your $1,000 principal), a little more than double, using simple interest and cash on cash. With compound interest, you would have more than a fourfold increase to $4,322. As you can see, for longer periods of time, cash on cash is inaccurate because unlike an ear of corn, interest can reproduce itself. That is the magic of compound interest reflected in the yield-to-maturity and yield-to-call calculations. If you want to have some fun, visit Google and type in "compound interest calculator" to find one. If you take the time to fully understand these concepts, your investment tree will grow many green leaves.

Chapter Notes

[46] James A. Klotz, "A Short-Term Outlook Leads to Long-Term Misery," www.fmsbonds.com, November 27, 2001, Commentary.

[47] Riva D. Atlas, "Enron Spurs Debt Agencies to Consider Some Changes," New York Times, January 22, 2002, C6.

[48] Aristotle, Politics, I, 10:5. According to Aristotle, money was incapable of reproducing itself, and therefore interest.