Chapter 23

Chapter 23

Evaluating mLearning

Cathy A. Stawarski and Robert Gadd

In This Chapter

This chapter focuses on evaluating formal and informal adult learning that is delivered via mobile devices (that is, mlearning) and on adapting traditional training evaluation methodology so that it can be applied to mobile learning. Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to

- describe common data collection methods used to evaluate instructor-led training and mlearning using the Phillips ROI Methodology

- identify methods that can be used to collect mobile learning evaluation data at Levels 1, 2, and 3

- discuss the rationale for changing the approach at these levels when evaluating mlearning

- recognize variables and issues that evaluators must consider when evaluating mlearning (for example, data collection ethics).

A review of the literature highlights various definitions of mobile learning (mlearning). Many definitions emphasize that the learning occurs using a device that is not tethered to a specific location (Wikipedia, 2009). Authors such as Traxler (2007) prefer to explore definitions of the “underlying learner experience” and how mlearning differs from other forms of education and learning. The focus of this chapter is on evaluating formal and informal adult learning delivered via technology that is easily transported using mobile devices and either used in isolation (that is, pure mlearning), or as part of a blended learning solution. Regardless, the learning was developed in accordance with standard principles of instructional design. Specific learning objectives are expected to be accomplished, application of the learning is expected to occur, and potential for organizational impact exists. The primary goals of evaluation are to improve both training and participant performance.

Transitioning from Classroom to Technology-Enabled Learning

With the advent of technology-enabled learning, training material is now covered in virtual classrooms in less time than it was in traditional classrooms. As classroom training is converted to e-learning, common estimates are that classroom “seat time” is approximately twice as long as that of e-learning (for example, CellCast Solution Guide, 2009). Of course, this estimate can vary, depending on the complexity of the content and level of interactivity. Regardless, when training programs leave the classroom in favor of online learning, more is covered in less seat time. Now, as mlearning becomes more popular, we are finding that training is developed in even smaller chunks of information. Whereas in the past we measured classroom-training time in terms of hours or days, we now measure mobile learning time in terms of minutes. After all, most people’s primary use and justification for owning and carrying a mobile device is on-the-go communications (phone calls and email), rather than as a learning appliance.

As mlearning evolves, it is transforming the definitions of training and education. With technological advances, approaches to training are becoming more creative. The popularity of mobile devices enables training developers to create material for learners on the go. Learners and workers are not limited to sitting at a desk. Personalized instruction can be delivered directly to mobile devices. Podcasts can be listened to at the gym, on a train, and in various other locations. Performance support tools, such as checklists, can be viewed and used on mobile devices. GPS coordinates can be accessed on mobile devices, providing opportunities to learn about locations as the learner is on location. With these advances in technology, instructional designers are creating tools and opportunities in such a way that the concepts of training and education are broadening and the lines between formal and informal learning are blurring. When one incorporates using mobile delivery with Web 2.0 tools and techniques (for example, wikis, blogs, and social media), the use of technology is affecting the learning experience in unseen ways. It is important to use the evaluation results for continuous improvement of the instructional methodology and materials.

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

mLearning units of instruction may be as short as two to five minutes.

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

Evaluation techniques must keep pace with evolving definitions of training and education.

Some authors (Vavoula and Sharples, 2009) have discussed the challenges of evaluating mobile learning and have attempted to capture the learning context in their evaluation framework. Sharples (2009) makes the point that mobile learning may be distributed, involving multiple participants in many different locations that offer learning opportunities. But, when they occur in informal settings (for example, museums), we will neither know how learners will engage in the learning activity, nor have specific learning objectives to achieve, making it more difficult to evaluate the learning. Although these are the types of variables that evaluators of mobile learning need to consider in the future, it is not the purpose of this chapter to measure the influence of context, or to compare mlearning to other types of learning formats. The purpose of this chapter is to focus on techniques that can be used to measure the achievement of learning objectives and organizational impact of adult mlearning experiences. The discussion is focused on ways to adapt traditional training evaluation methodology so that it can be applied to mobile learning.

Traditional Training Evaluation Approaches

Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluation (shown in table 23-1) comprise the most commonly used training evaluation framework (Kirkpatrick, 1998). Level 1, reaction, defines what participants thought of the program materials, instructors, facilities, and content. Level 2, learning, measures the extent to which learning has occurred. Level 3, job behavior, is defined as whether the participant uses what was learned on the job. Level 4, results, measures changes in business results, such as productivity, quality, and costs.

Although Kirkpatrick provided the initial framework for evaluating training and his work continues to be the most widely recognized (Twitchell, Holton, and Trott, 2000), Phillips attempted to move beyond Level 4 in the early 1980s. He redefined Levels 3 (application and implementation) and 4 (impact) to broaden their definitions by including transfer of learning and outcomes to processes other than training (Phillips, 1995). He also focused on what he called Level 5, return-on-investment (ROI). Phillips’ five levels, and common data collection methods used at each level, are shown in table 23-2.

Table 23-1. Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Framework

| Level | Measures |

| 1. Reaction | Participant reaction to the program |

| 2. Learning | The extent to which participants change attitudes, improve knowledge, and/or increase skills |

| 3.Behavior | The extent to which change in behavior occurs |

| 4. Results | The changes in business results |

Source: Kirkpatrick (1998).

Evaluating Traditional Training versus Evaluating mLearning

With instructor-led training or e-learning, one often uses extensive end-of-course surveys to measure reaction and learning. Tests or other class projects that demonstrate learning are also common. Further, supervisors are often contacted three to six months after training to determine whether learners have applied what they learned in class. Each of these data collection methods is time consuming for the learners and supervisors. When units of instruction become smaller and more numerous, as they are with mlearning, placing significant burden on the learner to provide evaluation data at the end of each unit is not desirable, nor is it appropriate to contact supervisors at the end of each mlearning unit of instruction to obtain feedback on application. Therefore, units either need to be bundled together in such a way that logical evaluation data can be obtained at the end of a bundle of units, or data collection needs to be streamlined at the end of each unit of instruction. One way to consider bundling units is by terminal learning objective.

Table 23-2. Common Data Collection Methods Using the Phillips ROI Methodology

| Level | Common Data Collection Method |

| 1. Reaction | End of course survey, action plans |

| 2. Learning | End of course survey, test, portfolio, facilitator assessment |

3. Application and Implementation |

Supervisor or participant survey, observation, focus groups, interviews, action plans |

| 4. Impact | Variety of sources |

| 5. ROI | Convert Level 4 data to monetary value using actual costs, extant data, other sources |

When mlearning or e-learning units are accessed via the Internet, collecting data without the learner’s knowledge is possible. For example, if you wish to know when, or how frequently, a participant accessed a specific learning unit to get a measure of whether the participant perceived the unit to be relevant, a password may be required to access each unit. Learning units (for example, podcasts or iPhone/BlackBerry/Android apps) that will be downloaded to mobile devices can also require a password to be downloaded for use on an individual’s own schedule, while using a personal mobile device.

Levels 1 and 2: Traditional versus mLearning

As shown in table 23-2, the traditional methods used for collecting Level 1 data at the end of classroom training are end-of-course surveys and action plans. When collecting reaction data, we often ask the following content-related questions:

- Is the training relevant to your job?

- How much new information was provided?

- Would you recommend the training to others?

- Do you intend to use the information covered in class?

- How important is the information to your job? (Phillips and Phillips, 2007)

Common Level 2 data collection methods include end-of-course survey, test, portfolio, and facilitator assessment. Key questions to be answered at Level 2 include

- Is there evidence of learning?

- Do participants understand what they are supposed to do?

- Do participants understand how they are supposed to do it?

- Are participants confident to apply skills and knowledge learned? (Phillips and Phillips, 2007)

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

Consider bundling mlearning units based on the targeted objectives.

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

Evaluators should always be cognizant of the potential for survey overload and minimize the burden on participants.

Designing the common data collection instruments and answering surveys, completing portfolios, or taking tests can be fairly labor intensive for evaluators and program participants. As described, at least nine common questions should be answered when evaluating traditional learning at Levels 1 and 2. Imagine how disruptive it would be to include nine or more questions at the end of every mlearning unit to evaluate whether it was effective. Participants could spend more time addressing evaluation questions than going through the mlearning unit itself. Therefore, evaluators need to get creative in their approach to evaluation at Levels 1 and 2, while continuing to keep the goals and objectives of the learning module in mind.

When collecting mlearning reaction data (Level 1) consider asking just two questions:

- Is the training relevant to your job?

- Do you intend to use the information covered in class?

A positive response to these two questions indicates that the learner understands the relationship between the material covered in the class and his or her job responsibilities. Intent to use the information, or planned action, is a good predictor of future application of the information (Phillips and Phillips, 2007). You can either ask these questions directly or consider other ways of measuring reaction. For example, accessing the learning units or job aids multiple times may be considered an indication of perceived relevance.

Data regarding the date, time, and frequency of access can be tracked in a database based on when the password was entered and would not require asking participants any questions. Unless downloaded units contain access information that can be synchronized at the end of a unit and entered into a central database, it will be more difficult to track the frequency of timing of accessing such units, compared with the ease of tracking units that are delivered directly from the Internet. Certain mobile devices (for example, smartphones) that can be used for mlearning do have access to the Internet and can effectively transmit back to the central database usage information regarding each learning unit. Any attempts to track users should be fully disclosed to all learners before any action is taken. As with any good evaluation, evaluators should consider multiple methods of collecting the data they are seeking.

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

Always consider ethical issues when evaluating mlearning.

If you are tracking which students access mlearning modules, consider asking those who do not access the module, “Why didn’t you access the module?” The answer to this question could give you information about student motivation and potential barriers in the environment.

When collecting mlearning Level 2 data, indicators of learning can be built into the learning unit or provided at the end of the unit. Correct answers to questions asked during or after the unit can be analyzed to determine whether learning is occurring. In addition, consider other methods of collecting data, such as asking participants to explain how they are supposed to use the information. Whereas simple multiple-choice responses indicate recognition of the correct answer, explaining how to use the information provides an estimate of comprehension, a higher level on Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Further, with the common practice of text messaging in today’s society, a brief explanation typed into a mobile device will be a minimal burden on students.

As mentioned earlier, to minimize the burden on respondents, it is best to bundle learning modules, for example, based on terminal objectives. The end of an mlearning bundle may be a good opportunity to ask the participants how confident they are to apply the skills and knowledge learned in the bundle. This might also be a good time to provide a short series of quiz questions. Anytime/anywhere content delivery via mlearning also provides an opportunity to package, deliver, and track reinforcement for any concepts learned today and largely forgotten tomorrow, ensuring knowledge gained stays front and center and is reused and reconsidered proactively.

Level 3: Traditional versus mLearning

The key questions typically asked to determine application of learning, Level 3, include

- To what extent do participants apply the knowledge and skills they learned?

- How frequently are participants applying these knowledge and skills?

- What supports participant application of knowledge and skills?

- What barriers are preventing the application of knowledge and skills? (Phillips and Phillips, 2007)

Answers to these Level 3 questions should be collected from individuals who observe the participant’s behavior and may include a self-report by the participant him- or herself. When we take these questions and apply them to a mobile learning application, data can be used to quickly customize training and improve performance if the data are collected online and monitored by the instructor.

For example, requiring participants to maintain an online journal or blog, answer regularly scheduled survey questions, or use an online performance support tool accessible on their mobile device can provide real time, or close to real time, application data. An online journal can be submitted as a text message and entered into a database or formatted as a blog. Depending on the specifics of the training, it may be appropriate to require a daily online journal that briefly summarizes application of learning that day and planned actions for the next day. By documenting planned actions for the next day, the participant may consider him- or herself more accountable for application, which may encourage more frequent application of learning. Barriers and enablers to application can be identified early when instructors monitor the journals and verify actual application or lack thereof. This provides an opportunity to intervene in the training program to either improve the overall learning module, or to customize the training pushed out to individuals who are encountering specific challenges. Because the goal of evaluation is to improve training and performance, real-time (daily) data collection and monitoring can provide opportunities to strengthen enablers and remove barriers or otherwise improve training in ways that ultimately improve performance.

If the instructor observes specific participants having challenges applying learning, he or she should ask simple survey questions regarding the barriers and enablers to application. Because text messaging is such a common behavior, responding to simple open-ended questions should provide a minimum burden to respondents. Depending on the length of your program and how long you monitor application, consider sending regular reminders to participants to update blogs or journals, or pushing out regularly timed (for example, weekly or monthly) survey questions.

If you ask supervisors for feedback on how their employees apply what they have learned, keep in mind that supervisors are very busy. Be judicious when deciding on the frequency with which you plan to contact them about their employees’ application of learning. At a minimum, bundle questions to supervisors by terminal objectives. Larger bundles may be desirable.

Practitioner Tip

Practitioner Tip

Bundle supervisor contacts as much as possible.

Level 4: Traditional versus mLearning

When examining organizational impact, the key questions to ask are

- To what extent have key measures improved as a result of the program?

- What measure(s) improved the most as a result of the program?

- How do you know it was the program that caused the improvement? (Phillips and Phillips, 2007)

The Level 4 evaluation process for mlearning often will be the same as with traditional training delivery. You will need to review organizational level measures and extant data reflecting measures related to your key business objectives. These measures are likely to reflect indications of increases or decreases in output, productivity, quality, cost, or time. If mobile training includes an electronic performance support system or is otherwise focused on job performance using technology, there may be a way to automatically measure time or output. Consider monitoring those trends over time. Be sure to consider all impact measures, not just those monitored via technology.

How do you know changes in the impact measures were a result of the mlearning program? If you’re following the Phillips ROI Methodology, you want to be sure to isolate the effects of the program in the same way you would with more traditional training delivery methods. Examples of common approaches to isolation include

- control/comparison groups

- trend-line analysis

- forecasting methods

- participant and/or manager estimation (Phillips and Phillips, 2007).

The method used to convert impact measures to monetary value is no different if training is delivered via mobile devices. Standard practices include using

- standard values

- participant and/or manager estimates

- historical costs

- internal/external estimates (Phillips and Phillips, 2007).

Level 5: Traditional versus mLearning

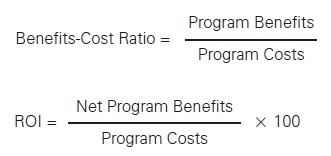

The ROI calculation will not change for training delivered via mobile devices. As shown below, calculate the benefits-cost ratio (BCR) by dividing the program benefits by the program costs. The return-on-investment (ROI) is then calculated by dividing the net program benefits by program costs and multiplying the result by 100 (see figure 23-1; Phillips and Phillips, 2007).

Figure 23-1. Phillips’ ROI Calculation Formula

Summary

Common training evaluation approaches, for example Kirkpatrick’s four levels and Phillips’ ROI Methodology, focus on the goals and objectives of the training. The focus of evaluating mlearning also should be on the goals and objectives of the training. Because mlearning units may be delivered in shorter segments than traditional classroom training or e-learning units, different approaches to collecting evaluation data may be warranted at Levels 1, 2, and 3; however, standard approaches to collecting data at Level 4 and calculating ROI are likely to be sufficient when evaluating mlearning. Also, because mlearning modules are delivered via technology, opportunities exist to use the technology to collect data. Timely data collection and monitoring can result in an evaluation system that enables customized individual training programs being delivered via mobile devices, potentially decreasing the time to performance improvement.

Case Application: Sales Quenchers

Case Application: Sales Quenchers

Sales Quenchers is a sales training organization that provides just-in-time reference materials to organizations. Their Mem-Cards were originally designed in traditional playing card format. The cards distill the core concepts and key techniques of leading sales experts. The Mem-Cards help busy salespeople learn new skills they can apply while selling. Unfortunately, the cards were difficult to update, reprint, and redistribute in their original format. It was also impossible to track who was using the cards. So, Sales Quenchers made the decision to convert the cards to a digital format. By going through this conversion, the Mem-Cards became mobile learning ready, and Sales Quenchers was able to offer a flexible subscription model and deliver its content to customers via cell phone, personal digital assistant, or computer. It also enabled supervisors to create and distribute custom content to their workforce, track completion of assignments, and measure retention of information.

Sales Quenchers used a mobile content and communications platform, CellCast Solution, from OnPoint Digital, to address its requirements. This fully integrated mobile content creation, delivery, and tracking platform supports mobile learning and information delivery initiatives, using essentially any telephone equipped with touchtone dialing. Managers, supervisors, and higher-level administrators can access, review, and analyze the collective results at any time. CellCast call tracking records time and frequency statistics for every interaction.

Level 1

The program was designed to include one or two interactive or open-ended survey questions gathering real-time feedback.

Level 2

Interactive open-ended survey questions are designed to measure knowledge retention. Test and survey questions are answered by pressing specified keys or giving verbal responses on the phone. Learners receive immediate feedback on test scores via email or text message. Managers receive test confirmations and can review scores and hear comments or read transcripts.

Level 3

The system facilitates just-in-time learning with search methods and tools integrated into the portal platform. The use of digital cards is tracked. The system also includes social networking capabilities. Comments can be monitored for evidence of application.

Level 4

Managers have access to call completion rates, best and worst performers, best and worst test scorers, top content contributors, monthly billing reports, and collective survey results and/or responses. This conversion to mobile learning is driving larger and broader sales into both current and new markets and sales channels for Sales Quenchers. Using the system to gain wisdom, insights, and a pep talk from industry-leading experts has translated to accelerated learning and increased sales.

Level 5

Although Sales Quenchers did calculate the cost savings when it converted to the digital format, a full cost-benefit analysis was not performed. Therefore, ROI was not calculated.

Source: Gadd (2008).

![]()

Knowledge Check: Designing an mLearning Evaluation Strategy

Now that you have read this chapter, try your hand at designing an evaluation strategy for a mobile learning unit. Check your answers in the appendix.

Flower Meadows is a garden store that has locations nationwide. They sell annuals, perennials, trees, gardening tools, and supplies. Their spring flowers are especially popular in cold climates. Sales have recently dropped more than would have been expected if it were simply due to difficulties in the economy.

Flower Meadows’ headquarters has developed training materials that can be accessed on mobile devices used by nursery workers. The suspicion had been that the spring flower sales have fallen due to problems fertilizing and watering flowers in the nursery. The new training materials include instructions regarding scheduling of plant care in various zones throughout the Flower Meadows sales areas. Daily checklists are included in the materials, enabling nursery workers to indicate that each required task has been completed. All nursery workers were required to complete the training at least one week prior to the beginning of the spring planting season in each zone, and to complete checklists each Friday during the spring season in each zone.

Five business objectives were established. The goal was to achieve each of the following objectives during the first two months of the spring season in each zone:

• increase sales of perennials by 10 percent

• decrease the number of annuals that must be discarded due to poor condition (for example, disease, lack of water) by 10 percent

• increase sales of plant fertilizer by 5 percent

• increase the number of repeat customers (defined as customers who buy flowers early in the spring and then return at a later point for additional products) by 8 percent

• maintain a minimum customer satisfaction rating of 92 percent.

One month into the spring season in each zone, supervisors were expected to report interim results to management and make any necessary corrections. At the end of the spring season, supervisors were expected to report final results for the season and recommend whether a similar approach should be taken for the fall season.

Following the steps described in this chapter, how would you evaluate the mlearning taken by the nursery workers? How would you attempt to measure success of each of the business objectives?

![]()

About the Authors

Cathy Stawarski, PhD, is the program manager of Strategic Performance Improvement and Evaluation at the Human Resources Research Organization (HumRRO) in Alexandria, Virginia. Her current work is focused on program evaluation, training evaluation, and individual and organizational performance improvement. She is a certified practitioner in the ROI Methodology.

Stawarski is coauthor of “Data Collection: Planning and Collecting All Types of Data” in Measurement and Evaluation Series: Comprehensive Tools to Measure the Training and Development Function in your Organization (2008). She has also delivered numerous conference presentations on topics related to training evaluation issues. She can be reached at [email protected].

Robert Gadd is president and chief mobile officer of OnPoint Digital, a leading supplier of online and mobile learning solutions to enterprise customers. Gadd oversees OnPoint’s technology and strategic direction in the design and delivery of diverse learning models and enabling knowledge transfer through e-learning, mlearning, and social-enabled performance portals. He can be contacted at [email protected].

References

Gadd, R. (July 2008). Sales Quenchers Case Study: Delivering Learning Nuggets by Smartphone. eLearning Guild’s Learning Solutions eMagazine, 1–9.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1998). Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

OnPoint Digital, Inc. (2009). CellCast Solution Guide. Savannah, GA: OnPoint Digital, Inc.

Phillips, J. J. (Summer 1995). Corporate Training: Does It Pay Off? William & Mary Business Review, 6–10.

Phillips, P. P. and J. J. Phillips. (2007). The Value of Learning. San Francisco: Wiley.

Sharples, M. (2009). Methods for Evaluating Mobile Learning. In G. N. Vavoula, N. Pachler, and A. Kukulska-Hulme eds. Researching Mobile Learning: Frameworks, Tools and Research Designs. Oxford: Peter Lang Publishing Group, 17–39.

Traxler, J. (2007). Defining, Discussing and Evaluating Mobile Learning: The Moving Finger Writes and Having Writ.... The International review of research in Open and Distance Learning 8(2), available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/3115019/Traxler-Defining-Discussing-and-Evaluating-Mobile-Learning.

Twitchell, S., E. F. Holton III, and J. W. Trott Jr. (2000). Technical Training Evaluation Practices in the United States. Performance Improvement Quarterly 13(3): 84–110.

Vavoula, G. N. and M. Sharples. (2009). Challenges in Evaluating Mobile Learning: A 3-level Evaluation Framework. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning 1( 2): 54–75.

Wikipedia. (October 24, 2009). mLearning, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MLearning.