FOUR

False Assumptions, Broken Models, Wasted Effort

CHAPTER SUMMARY: This chapter looks at the failed strategies and tactics that organizations have used to try to systematize and foster applied and organic innovation, including innovation clusters, Silicon Valley outposts, and dedicated corporate innovation teams. We examine why all these strategies have failed, and why it has been so hard to replicate the magic of Silicon Valley.

Some readers will recall the halcyon innovation days of the 1990s, when everything seemed possible and governments invented various strategies to spur innovation in entire cities. Remember the announcements about science parks and Silicon Valley–like tech hubs that they called industry clusters? Alas, most of those triumphant ideas have been debunked, and most of the attempts to spark top-down innovation fashion have quietly fizzled.

There are important lessons for businesses and governments to learn from these failures. Development of innovation centers is and always will be organic, from the bottom up. And though business executives love to have them, corporate Silicon Valley outposts are boondoggles: innovation by osmosis doesn’t work very well, partly because the outposts—treated as shiny baubles rather than core parts of product development—are removed from the company and do not tend to face the same pressures to survive and thrive.

Corporate innovation centers, too, fail most of the time. Assigning innovation to parts of an organization limits possibilities and corporate buy-in and creates useless innovation bubbles. More broadly, increasing research and development (R&D) spending in a vacuum or even with a relatively strong plan tends not to work: there has been no clear correlation between levels of R&D budget and corporate performance. Money alone can neither buy innovation nor change corporate culture to become more innovative and faster moving.

On the other hand, we have strong evidence that creating an innovation culture, or a culture that encourages and prizes key precursors to innovation, will generate improvements. It is all about focusing on your people. And doing that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg. The last section of this chapter will allude to the effect of culture, which we will address in greater detail later in the book.

The Failure of Industry Clusters

By the 1960s, Silicon Valley had already cemented its position as the world’s preeminent technology center. The Valley commenced its journey with the commercialization of the electronics industry, establishing key industry–academic partnerships that generated a positive feedback loop between nearby Stanford University and the high-tech Valley companies. French president Charles de Gaulle visited the Valley and was impressed by its sprawling research parks, set amid farms and orchards south of San Francisco.

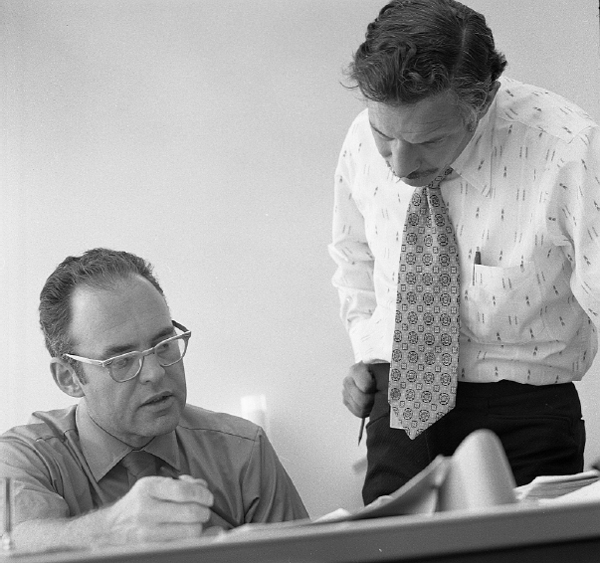

Figure 4.1 Gordon Moore (left) and Robert Noyce in 1970, having founded Intel in 1968 when they left Fairchild Semiconductor.

Image Credit: Intel Free Press

Classic Cluster

The early team at Fairchild Semiconductor, in San Jose, California, made the first integrated circuit, from silicon. Two of the team’s members, Gordon Moore and Robert Noyce (pictured in Figure 4.1), went on to found Intel.

Stanford had already given birth to successful companies, including Hewlett-Packard (HP), Varian Associates, Watkins-Johnson, and Applied Technologies. (HP, of course, went on to become an iconic brand, and remains in existence two decades into the 21st century.) These companies expanded the frontiers of technology, and from them came more companies, which focused on building innovations and symbiotic relationships. The resultant networks laid the conceptual foundations for the largest assembly line of technology powerhouses—and arguably the largest amount of corporate wealth creation—ever witnessed. Something unusual was happening here, in both innovation and entrepreneurship.

Unsurprisingly, other regions recognized Silicon Valley’s success and attempted to replicate its dynamics. The first significant attempt to re-create Silicon Valley emerged from a consortium of high-tech companies in New Jersey in the mid-1960s (though it should be noted that the Radio Corporation of America and its offshoot the David Sarnoff Research Center, founded in New Jersey, were innovation engines pre-dating the Valley by decades).

The New Jersey consortium recruited Frederick Terman, who was retiring from Stanford having served there as provost, professor, and engineering dean. Sometimes called the “father of Silicon Valley,” Terman had transformed Stanford’s young engineering school into an innovation juggernaut. By encouraging science and engineering departments to cooperate closely, linking them to nearby entrepreneurs and like-minded companies, and tightly focusing applied research on solving industry problems, Terman had created a culture of cooperation and information exchange that quickly took root and today still defines and shapes Silicon Valley.

New Jersey wanted to clone that dynamic and its powerful outcome. The Garden State was already a leading high-tech center: it was home to the laboratories of 725 companies, including RCA, Merck, and Bell Labs. It boasted a science and engineering workforce of roughly 50,000; but, with no prestigious engineering university in the area, New Jersey companies had to look outside for recruits. This was before the rise of New York University, Rockefeller University, and the various state universities of New York as research powerhouses. And even though Princeton University was nearby, its faculty back then mostly avoided applied research or close associations with industry. (Oddly though, making atomic weapons for the government was fine.) So, led by the top management at Bell Labs, New Jersey’s business and government leaders charged Terman with building a university that resembled Stanford.

Terman created a plan to accomplish that, but he was unable to obtain the consensus necessary to enact it—because, curiously, the very industry seeking this change wouldn’t and couldn’t collaborate in it. As documented by Stuart W. Leslie and Robert H. Kargon in a 1996 paper titled “Selling Silicon Valley,” RCA would not sign a partnership with Bell Labs; Esso elected not to embed its best researchers into a university; and drug firms such as Merck preferred to keep their research dollars in house.1 Even though they knew that working together would make them all better in the long run, companies refused to work with competitors.

Terman attempted a similar plan in Dallas. He failed there too, for similar reasons.

Later, the renowned Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter proposed a different method of creating regional innovation centers. Rather than rely on corporate cooperation, Porter proposed tapping existing research universities. His simple observation—not a novel one—was that geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and specialized suppliers offered knowledge-intensive industries productivity and cost advantages. In addition, the collective bubbling intellectual capital would, he posited, spur the creation of new firms. Porter postulated that in mixing these ingredients, as in adding ingredients to a pot of soup, regions could create clusters of innovation.2

Porter and legions of consultants espousing this methodology installed top-down clusters for governments all over the world. The formula was always the same: pick a hot industry, build a science or innovation park next to a research university, provide subsidies and incentives for the chosen industries (say, biotech or semiconductor research) to locate there, and seek a pool of venture capital.

It was an innovation catastrophe.

Sadly, the soup never came to a boil—anywhere. Hundreds of regions all over the world collectively spent tens of billions of dollars trying to build small, top-down replicas of Silicon Valley. We cannot cite a single success that is truly self-sustaining and innovative in the way that Silicon Valley is innovative. It was easy to identify the ingredients for innovation. As it turns out, however, the recipe was less obvious.

What Porter and Terman failed to realize was that neither academia, industry, nor even the U.S. government’s funding for military research into aerospace and electronics was a key catalyst in creating Silicon Valley; rather, it was the people and the relationships that Terman had so carefully fostered among Stanford faculty and industry leaders. That painstaking and non-transactional process had yielded immense and self-propagating social and intellectual capital that has maintained dominance over global innovation for nearly 50 years.

The Missing Ingredients: Culture, People, and Genuine Connection

University of California, Berkeley, professor AnnaLee Saxenian has cogently exposed the importance of culture, people, and connections in building innovation. Her 1994 book Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley insightfully compared the evolution of Silicon Valley with that of Route 128—the highway ring around Boston—to explain why no region has been able to replicate the California success story.3

Saxenian explained that, until the 1970s, Boston was significantly ahead of Silicon Valley in startup activity and venture-capital investments. The region had birthed numerous important technology companies in that era, including Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), one of the most powerful and profitable computer companies of its day, and Wang Laboratories. In fact, Route 128 had a real information-concentration advantage because of its proximity to East Coast industrial centers. Silicon Valley was closer than that to some aerospace production in Southern California, but the sheer volume of nearby industrial activity was much greater on the East Coast and the near Midwest during that era.

Despite Boston’s head start, by the 1980s, Silicon Valley and Route 128 looked alike: a mix of large and small tech firms, world-class universities, venture capitalists, and military funding. And then Silicon Valley raced ahead and left Route 128 in the dust. Today, Boston remains a distant second in receipt of venture-capital funding, in the value of companies created, and in total job creation from venture-backed companies: one metric that many accept as a relatively strong proxy for innovation.

The factors that let Silicon Valley outshine Route 128 were, at root, cultural. Silicon Valley experienced high rates of job-hopping and company formation. The professional networks and easy information exchange were more fluid and accepted. These soft traits lent the Valley advantages. Valley firms understood that collaborating and competing at the same time led to success. This even showed up in state laws: California barred noncompetition agreements, discouraging litigation against former employees. (For this reason, many of the world’s largest hedge funds and financial institutions to this day refuse to employ knowledge workers in California—revealing much about those institutions and their views on innovation!)

The Power of an Open System That Welcomes Outsiders

The Valley’s novel ecosystem supported experimentation, risk-taking, and sharing of the lessons of success and failure. More explicitly, Silicon Valley was an open system—a thriving, real-world social network that existed long before Facebook. To be clear, throughout history we have seen similar roots of innovation. Holland shared many of these traits during the centuries in which the Netherlands—a small, waterlogged country with a small population—was responsible for an astounding number of innovations and a wildly disproportionate share of global economic activity. Long before the Valley, Holland was a social network that rewarded risks and thrived on the open movement of ideas and people. Holland also shared another trait with Silicon Valley: openness to other ways of life and other cultures. Because it was happy to accept and embrace without conditions the best and the brightest people, Silicon Valley became a magnet for global talent.

From 1995 to 2005, 52.4 percent of engineering and technology startups in Silicon Valley had one or more founders born outside the United States, according to research conducted by Vivek at Duke University with the help of AnnaLee Saxenian of UC Berkeley.4 That was twice the rate seen in the United States as a whole. Immigrants such as Vivek who came to Silicon Valley found it easy to adapt and assimilate. The rules of engagement were openly shared, and the Valley’s inhabitants both participate in existing networks and create their own networks. (For South Asians, for example, The Indus Entrepreneurs, or TiE, grew to become a powerful sub-network within the broader Silicon Valley context.)

You read about the PayPal Mafia or the diaspora of early Apple engineers who went on to form their own successes. These networks cross-pollinated or merged as convenient, as did for example Tony Fadell, one of the key designers and product minds behind the iPod, in founding the home-thermostat company Nest, which Apple’s rival Google acquired for $3.2 billion.5

Equally important, in this network, all participate as relative equals. Yes, a founder who sold a company for a billion dollars or an engineer with a pedigree from storied Valley firms has a leg up in starting companies. But it is absolutely the case that dreamers with a paper napkin for a business plan can still get an audience with some of the smartest and most powerful people in Silicon Valley if they are persistent, polite, and persuasive.

This freedom to form relationships and share ideas is, more than anything else, what innovation requires. The understanding of global markets that immigrants bring with them, their knowledge of different disciplines, and the links that they provide to their home countries have given the Valley an unassailable competitive advantage as it has evolved from making radios and computer chips to producing search engines, social media, medical devices, and clean-energy technology.

The Valley is a meritocracy that is, however, far from perfect. And some of its flaws tear at the very fabric that makes it unique. First, women and certain minorities, such as blacks and Hispanics, are largely absent from the ranks of company founders and boards despite diversity’s having become a top priority for all Valley companies and venture capitalists. This is likely to be a barrier to the Valley’s further growth and has probably motivated it to focus on certain types of problems and ignore others. (Biotech and pharma startups focusing on women’s health and conditions that disproportionately affect people of African descent, for example, have consistently been shortchanged.)

In addition, venture capitalists have a herd mentality and largely fund startups that produce short-term results—leading to a preponderance of social media, advertising-technology, and blockchain apps.

Also problematic is that the Valley environment values money so highly that even top venture capitalists are willing to overlook repugnant behavior and toxic corporate leadership, both of which we witnessed for years throughout the growth of the ride-hailing company Uber and in the medical-technology company Theranos (where a culture of dishonesty was repeatedly called out but consistently ignored).

Finally, real-estate prices and home-rental rates are so high that most Americans (or people from any other country) can’t afford to relocate there, so it is becoming harder to maintain the open flow of people, the Valley’s lifeblood.

Though real and serious, these challenges arise only because of the Valley’s success and power. No one cares about trying to save an isolated regional innovation cluster that spent hundreds of millions of hard-earned state subsidies in vain to build an innovation engine. And few people believe, anymore, that you can impose innovation from the top down as a regional cluster. It’s a bankrupt idea. Yet, like a zombie, it continues to play out as a slow-motion failure all over the world. In 2012, the Monitor Group filed for bankruptcy, saddled with debts and unable to pay its bills. This high-powered consulting group had once been one of the loudest proponents of industry clusters—and its founder was none other than Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter.

Silicon Valley Outposts: Boondoggles and Junkets

The property at 3521 Hillview Avenue sits in the middle of Silicon Valley history. A stone’s throw from the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), which birthed so many early technology innovations, and a five-minute drive (or bike ride) from the campus of Stanford University, the beautiful glass building, tucked into a quiet street, is the Valley outpost of the Ford Motor Company. Dubbed Ford Greenfield Labs, the facility houses hundreds of Ford workers—and, in many respects, the future aspirations of Ford. There, engineers from Stanford and Apple work on autonomous vehicles, new ways to use sensors, and other cutting-edge concepts that Ford believes it will need in order to effectively compete in the uncertain future of the transportation industry.

There are nearly a thousand corporate outposts in Silicon Valley, in a number of flavors, few of them successful. Corporate venture funds invest in startups. Corporate incubators provide office space and mentors in order to develop solutions to the corporation’s problems. Corporate accelerators provide seed funding and support intrapreneurs within corporations. Corporate partnerships occupy corporate business-development offices. And, finally, there are specialized R&D centers such as Ford Greenfield Labs to attract local technology talent and, ideally, transfer some of their expertise back to the corporations.

This setup totals billions of dollars each year in annual expenditures and investments. And the rationale is laudable. In the case of Ford, the perceived threat to the company’s future is real. Autonomous vehicle technology is advancing quickly inside tech companies (such as Google and Apple) that in 2010 would not have registered as possible competitors. Google has the early data lead, with its Waymo division logging a vast advantage in the total vehicle–mileage of its driverless cars. As we mentioned earlier in this book, in an era of exponential competition, threats can readily arise from totally unrelated companies seeking to crack new markets.

Ford’s reaction—opening a lab to immerse itself in the action—is common. Unfortunately, the history of setting up corporate outposts close to the innovation action has shown few successes. But this has not prevented hundreds of major companies from setting up shop in Silicon Valley in one form or another, ranging from full-blown labs to R&D centers such as that of Ford (and many other automakers).

The Reasons for Outposts’ Failures

There are many reasons for the failure of these well-intentioned forays.

Lack of Real Commitment

For starters, there’s the element of commitment. For the most part, these outposts are helmed by executives or promising young employees from the corporate mothership who struggle to “get” the culture of the Valley. They arrive with good remuneration packages, few ties, and a loose charter to “help the company understand what’s happening.” A Silicon Valley outpost is rarely held to a specific goal, and even when it is, accountability tends to be fluid. This is a major problem, as it makes the outpost nothing more than a junket and fact-finding mission with little real output or rationale.

Isolation from the Mothership

In addition, these outposts tend to be isolated from their mothership. Most outposts are several time zones, if not a continent, away from their main company, loosening even their temporal bonds. This distance results in less contact and in mutual unawareness. And, because there is no formal way to transmit information back to the mothership, even if the occupants of the outpost are diligent and manage to understand the Valley, the information they capture and the social capital they gain is hard to transfer home.

Best Employees Are Hired Away

The outposters also realize that their outpost is always a tenuous line item, subject to cuts whenever the mothership experiences deterioration in its balance sheet or merely a change in leadership. It is, in the parlance of Wall Street, a “non-core asset.” So the best outpost employees tend to get hired away by smart startups or by legacy technology players who recognize their value well before their mother corporation understands it. And the worst of them view their posting as a plum gig in an awesome part of the world that they can use as an innovation credential for their next stop on the corporate merry-go-round.

In a nutshell, the outpost arrivals—both individual and organizational—are not necessarily in Silicon Valley for the long haul.

The Antithesis of the Valley Ethos

Such mutual uncertainty is antithetical to the attitude and approach that have made the Valley successful and that allow new entrants to thrive: a clear commitment to long-term participation and contribution. None of this is to say that the outposters’ intentions are bad or that the mothership is unjustified in wanting a piece of the Valley. But just showing up—even with a specific idea in mind—doesn’t enable innovation.

Hiring Valley Leaders Doesn’t Work, Either

Another approach is to hire existing Valley leaders and talent to staff an outpost. The theory is that they will bring over their networks and values and enable the company to take advantage of their social and intellectual capital. In reality, though, corporate headquarters are generally reluctant to devolve much true authority and autonomy to their outposts, which instead assume largely consultative roles.

This outpost is unable to provide more than an R&D capacity hard to obtain elsewhere. Silicon Valley is home to many more autonomous-vehicle engineers than is Detroit—but they are not coming from an automotive background. So these imported outpost leaders almost always depart, frustrated, to return to one of the big tech companies whence they came. The sad reality is that the top talent does not want to work for legacy corporations.

Inability to Match Tech Companies’ Compensation Packages

What’s more, legacy corporations can’t match the compensation packages that the leading technology companies offer. So either they hire short-timers who may be very good but are taking it easy for a bit in a corporate gig, or they hire those who have been unable to stay at Google, Apple, and other leading organizations.

Inability to Solve Real Problems because of Disconnection from Real Customers

More fundamentally, though, corporate outposts do not solve the sponsoring organization’s core problems, and they remain disconnected from the organization’s customers and corporate needs. Residents of an outpost will continue to receive the emails and slide decks and will continue to sit in on the all-hands phone calls. But, because they are no longer talking to customers or the sales team or others on the front line, outposters lose touch with the true needs and wants of the customers.

Moreover, most Silicon Valley outposts are—as are outposts anywhere—too small in scale to drive real disruption and innovation. This is underscored by the tendency of outpost employees to do things in the same way they are done in their legacy corporation: with little passion or sense of urgency, and with a heavy reliance on specialization and multiple departments.

Venture Capital Spreading More Broadly

Another important consideration is that, over time, venture capital and innovation have begun to spread more broadly. Stockholm, Beijing, London, and New York all host thriving innovation ecosystems. China has created a powerful circular innovation engine by working with Chinese nationals who are educated in the United States and Canada and who return to China to work in engineering or research roles in their country of birth. China is now the fastest-growing pool of venture-backed startups and is racing ahead in innovation.

So, although each innovation ecosystem has followed its own path to some degree, their commonalities mirror the development path of Silicon Valley, and their common ethos is more similar than dissimilar to Silicon Valley’s. And all of those successes are long-term projects that, far from relying upon osmosis, result from painstaking reciprocal, non-transactional relationship building: the creation of a valuable social network that cannot be replicated or mocked up merely by renting some prime real estate in a hot location and airdropping in a team from the mothership.

Ford Labs Was Not Enough

In the end, Ford realized that Greenfield Labs was not going to solve its problems of navigating the new challenges of mobility and transportation. The labs remained, but the company also decided to invest billions of dollars in a slate of well-regarded autonomous transportation startups, including Argo and Rivian. We’ll discuss later why this invest-in-the-best strategy, executed properly, outperforms an innovation outpost in terms of corporate innovation.

The Folly of Dedicated Top-Down Corporate Innovation Teams

Companies with a long track record of innovation usually bend over backward to include everyone as a potential innovator. Many large companies, though, attempt—often at the behest of corporate consultants—to spur innovation by creating an internal innovation team. Generally comprising stellar employees who excel at climbing the corporate ladder (many of whom have obtained an innovation credential from an association of innovation professionals in order to become “innovation experts”) and tell the company what works and what doesn’t, the innovation team’s mandate is usually to seek innovation and bring the best on offer into the company.

Sometimes corporate innovation teams look to bring in startups as partners. Sometimes they work with their companies’ venture-capital arms seeking strategic investments in startups that could be disruptive in their industries. Many corporate innovation teams oversee internal startup competitions and funds, and often serve on committees to judge startup performance and allocate their next funding round among them.

A separate location is usual for the internal innovation team and internal startups—which, as this chapter has illustrated, all too often results in an innovation black hole, albeit one with bright colors and bean bags strewn about.

All these tendencies can, and usually do, create counterproductive incentives, bogging down corporate innovation by poisoning innovation efforts. As do those in corporate outposts, innovation teams struggle to identify, let alone focus on, customer problems. Without real power to make things happen, and without real budgets, they turn over quickly, because their most perceptive members realize that this is not an effective way to enact change in a company. Thus do the vast majority of corporate innovation efforts—more than 90 percent, according to one study by the consultancy Capgemini and Altimeter Group—fail.6

Innovation Teams Can’t See New Business Models

The biggest problem that all these flavors of canned innovation face is one of recognizing a change in business model. Changing a business model is far more painful and harder to comprehend than bringing in a new technology. This is why it takes a radical startup such as Lyft or Uber to bring something that is head-smackingly obvious into the light, such as the concept of attaching demand to supply for transportation via smartphones. It’s why almost all of the legacy I.T. giants (Microsoft being an exception), including Oracle and IBM, are struggling to compete in a world of cloud computing in which server space is divided into smaller and smaller pieces and sold off by the hour or by the minute—and in which a simple move such as attaching a mail-order option and turning razor blade sales into a subscription business can enable a small startup to snatch 10 percent of the multi-billion-dollar North American market for men’s shaving products.

Innovation Teams Struggle to Identify Nascent Markets

The famed venture capitalist Marc Andreessen is best-known for his visionary op-ed in the Wall Street Journal titled “Why Software Is Eating the World.” But those who follow him closely also know that Andreessen feels that software alone is not sufficient to eat the world and grow giant companies. In a less-famous blog post, Andreessen states his opinion that neither the quality of the team nor the quality of the product matters nearly as much as market demand for the innovation’s projected benefits. “In a great market—a market with lots of real potential customers—the market pulls product out of the startup. The market needs to be fulfilled and the market will be fulfilled, by the first viable product that comes along,” Andreessen wrote in a post titled “The Only Thing That Matters.”7

Corporate innovation teams struggle mightily to supply these nascent markets, because they cannot walk a mile in the shoes of their customers. Judging or generating ideas for others to execute is a poor vantage point from which to see opportunities for market innovations that lead to successful products. For that, you need an evangelical zeal that can come only from a true founder mentality and a true emotional buy-in and commitment to the process of building something from nothing.

We have covered some of the ways in which innovation efforts have failed. Industry clusters can’t be readily engineered and tend to sputter out: while a Silicon Valley outpost offers an alluring prospect of bellying up to the beasts of innovation, osmosis is a weak force for absorbing innovation culture, let alone transplanting it into an organization that is struggling to reinvent itself. Likewise, corporate innovation teams tend to fail because they are top down, set apart from the rest of the company, and trapped in an ivory tower disconnected from reality. Bad ideas follow, money is wasted, and innovation gets lost in the shuffle.