p.410

FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT MOTIVATED BY INSTITUTION SHOPPING

Mike W. Peng and Young H. Jung1

Introduction

Why do multinational enterprises (MNEs) undertake foreign direct investment (FDI)? The number of MNEs that undertake FDI is increasing. The number of MNEs worldwide was approximately 7,000 in 1970, and increased to approximately 82,000 in 2009 (UNCTAD, 2009). The number of countries that receive FDI flow was 121 in 1970 and 201 in 2014 (UNCTAD, 2015). Since the 1970s, the world economy has witnessed the participation of the developing countries in East Asia, the transition economies in Central and Eastern Europe, and the emerging economies such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC). These countries have not only become major recipients of FDI, but have also become breeding grounds for new multinationals that undertake significant outward FDI.

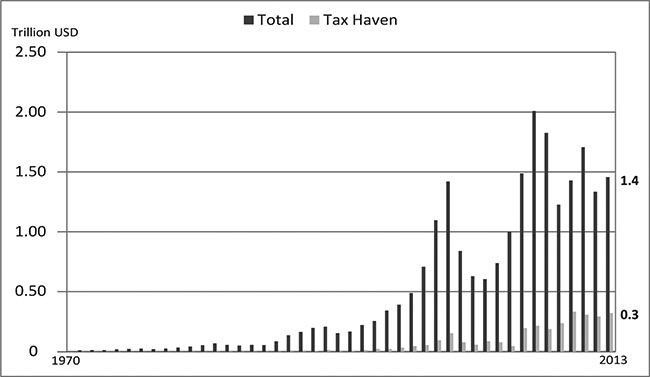

Conventional FDI research focuses on MNEs from developed economies (DMNEs) that already hold competitive advantages in their capabilities and exert such capabilities in foreign venues by seeking new markets or low-cost factors (Dunning, 1988, 1993). In short, these motives can be summarized as asset-based. However, the increase of participants as well as the spatial expansion of the world economy has brought gradual but dramatic changes to the landscape of FDI. First, MNEs from emerging economies (EMNEs), equipped with fewer competitive advantages than DMNEs, have increasingly undertaken FDI in developed economies as well as developing economies (Mathews, 2006; Peng, 2012; Xia, Ma, Lu & Yiu, 2014). Second, also surging is FDI toward destination countries with neither natural resources nor capable labor forces but lower corporate tax rates (Hines, 2010). These destination countries are often known as tax havens. Figure 24.1 illustrates that tax havens hold 22% of total FDI flows of the world, reaching $322 billion in 2013 (UNCTAD, 2015). These two phenomena have not been sufficiently addressed by the conventional asset-based motives of FDI, given that EMNEs may not be competitive undertakers of FDI and low-tax countries may not be attractive FDI destinations in view of asset-based perspectives.

Focusing on EMNEs, the recent literature on FDI posits that EMNEs are leveraging FDI in order to obtain competitive advantages with respect to technology or innovation, and that EMNEs are mitigating competitive disadvantages by escaping from non-transparent institutions of home countries (Luo & Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007). As is shown in Figure 24.2, this FDI research shows significant theoretical development by providing a new category of motives in accordance with the institution-based view (Peng, Wang & Jiang, 2008; Peng, Sun, Pinkham & Chen, 2009). This new category of institution-based motives is different from traditional, asset-based motives. In spite of such progress, however, the literature does not fully address the MNEs’ motive of FDI to seek specific institutions that offer benefits or mitigate costs of MNEs such as lower tax.

p.411

As depicted in Figure 24.2, we offer a complementary institution-based perspective on FDI and extend the existing frameworks, based on the analysis of costs and benefits provided by institutions. First, we define institutional benefits as the sum of the positive effects from a country’s institutional factors that enhance firms’ competitive advantages, whereas institutional costs are the sum of the negative effects from a country’s institutional factors that diminish firms’ competitive advantages or increase disadvantages. Second, we posit that, other conditions including resources being equal, MNEs may endeavor to maximize their net institutional benefits overall. Third, we argue that MNEs “shop around the world” to look for specific institutions that enhance firms’ overall net institutional benefits. In short, they engage in “institution shopping”. Finally, we probe two behaviors of shopping for institutions: (1) avoiding misaligned institutions that incur institutional costs, and (2) leveraging loopholes in the entanglement of institutions that provide institutional benefits.

p.412

We endeavor to make three contributions. First, we probe the costs and benefits of institutions, furthering the analysis on MNEs’ choice of institutions beyond developed or underdeveloped institutions. Second, we shed new light on the countries attracting FDI inflows by offering institution-based benefits in spite of little asset-based appeal to MNEs. Third, we explore the active engagement of MNEs in order to maximize the benefits from the entangled institutions in the global setting of MNEs’ business. Overall, we would advance our contributions to the FDI literature by extending conventional motives of FDI toward a comprehensive framework that may provide an overarching explanation on the FDI of both DMNEs and EMNEs that seek institutional benefits.

Conventional FDI motives

Asset-based perspectives on FDI

Why do firms undertake FDI? Constellations of literature have endeavored to answer this long-standing question in International Business (IB). Although their perspectives may not be identical, one of the common assumptions of the FDI literature would be that MNEs undertake FDI when the benefits from FDI exceed the costs. DMNEs may be the first group that took the initiative of such benefits from cross-country operations, and the eclectic paradigm of Dunning (1988, 1993) would be one of the principal theories that explain why and how DMNEs undertake FDI.

The eclectic paradigm, popularized as the ownership-location-internalization (OLI) framework, provides a theoretical framework on FDI with three analytical lenses: ownership (O), location (L), and internalization (I). The O-specific assets refer to MNEs’ exclusive possession of intangible assets that may be transferred within the cross-border value-added activities of MNEs. The L-specific assets indicate the economic, political, and social benefits proffered by host countries. The I-specific assets are MNEs’ capabilities of adding value to the O- and L-specific assets with their organizational efficiency (Dunning, 1988, 1993; Denisia, 2010). The advantages stipulated in the OLI framework are competitive advantages of MNEs from the comparison of firms’ privileged intangible assets, proffered benefits from host countries, and firms’ value-added organizational efficiencies that may not be held by competitor firms.

The OLI framework explains FDI based on asset-seeking motives. MNEs undertake FDI in order (1) to explore new market opportunities in different countries, (2) to procure natural resources that are not obtainable in their home countries, (3) to secure efficiency—with lower acquisition costs than those in the home country, and/or (4) to pursue strategic imperatives of international competitiveness (Dunning, 1993; Peng, 2014a). In other words, the OLI framework assumes that MNEs undertaking FDI retain competitive advantages such as the O-specific and I-specific assets that create advantages with L-specific assets provided by the destination of FDI.

p.413

Then, what about FDI undertaken by MNEs with no such asset-based competitive advantages? Recent trends in global FDI witness the expansion of EMNEs that lack their own O-specific assets such as technological advantages or managerial capabilities compared with DMNEs (Makino, Lau & Yeh, 2002; Barnard, 2010; Gammeltoft, Barnard & Madhok, 2010; Peng, 2012). Scholars suggest that EMNEs go abroad, not because they have and hold competitive advantages of O-specific assets, but because they attempt to obtain the competitive advantages of O-specific assets (Mathews, 2006; Peng, 2012; Xia et al., 2014).

In complementing the OLI framework that does not offer theoretical explanation of EMNEs’ pursuit of O-specific assets, Mathews (2006) proposes an alternative framework of linkage-leverage-learning (LLL). Linkage refers to the relationship-building orientation of EMNEs in order to acquire assets (Peng & Luo, 2000). Leverage refers to the capabilities of EMNEs to link or ally foreign business entities in order to leverage assets owned by such foreign entities (Sun et al., 2012). Learning refers to the process of repeated linkage and leverage by EMNEs that enables them to obtain targeted O-specific assets such as technology, managerial know-how, or innovation (Zahra, Ireland & Hitt, 2000). In sum, the LLL framework complements the OLI framework with respect to the FDI of EMNEs that endeavor to source O-specific assets (Peng, 2014a). However, the LLL framework is also based on asset-based motives in the same way as the OLI framework.

Emergence of an institution-based perspective on FDI

The asset-based perspectives such as the OLI and the LLL frameworks share the assumption that MNEs undertake FDI in order to seek and obtain tangible and intangible assets to enhance competitive advantage. However, there exists some FDI that may not be explained by asset-based perspectives. Why do many US MNEs establish headquarters in a small island country that scarcely has any resources? How do many DMNEs pay minimal tax to local governments in spite of the substantial amount of sales in the country? Suppose a country maintains the social institutions of labor that are so inflexible that the institutions do not permit the termination of employment contracts at the employer’s will. If an MNE decides to leave the country and undertakes FDI to operate in another country that maintains flexible labor institutions, such FDI undertaking may not be the case of asset-seeking, but rather that of institution-seeking.

This hypothetical anecdote would be explained using the institution-based view, one of the principal lenses to analyze IB (Peng, 2014a). Institutions would influence and determine the scope of the operation of MNEs, particularly when it comes to the influence from the link of institutions between home and host countries (Peng, Lee & Wang, 2005; Peng, Wang & Jiang, 2008). The influence from institutions of a country may incur institutional costs that diminish firms’ competitive advantages or institutional benefits that enhance their competitive advantages. Thus, when institutions of home and host countries are linked, institutional costs and benefits would also be linked, and MNEs may endeavor to maximize net institutional benefits from overall cross-country operations (Hill & Hoskisson, 1987; Stevens, Xie & Peng, 2016). Therefore, MNEs may avoid institutions that are not aligned with the needs of MNEs, or seek institutions that provide the opportunity to leverage regulatory loopholes between different countries.

The literature exploring institution-based motives of FDI has focused on the avoidance of institutional misalignment by EMNEs in their home countries, especially emerging economies, based on the assumption that the institutional development of emerging economies is not as advanced as that of developed economies (Luo & Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007). Such literature does not shed light on the similar behavior of DMNEs that also escape from advanced but unfriendly institutions of their home countries, i.e., developed economies. To begin filling such a gap found in the current research of institution-based motives of FDI, we probe the institution-seeking behavior of MNEs toward a comprehensive understanding of the institution-based motives of MNEs, with the introduction of “institution shopping” below.

p.414

Institution shopping: toward a comprehensive perspective

Drawing from the “shopping” metaphor, institution shopping refers to the aggressive institution-seeking behavior of MNEs to search and reach a specific set of institutions that enhances institutional benefits or mitigates institutional costs. We argue that institution shopping may be derived from (1) the motive to escape from the misaligned institutions that diminish competitive advantages, or (2) the motive to leverage loopholes in the institutions that enhance competitive advantages.

Misalignment avoidance

Some MNEs undertake FDI in order to escape from institutional hurdles in their home country (Boddewyn & Brewer, 1994). In other words, MNEs would escape their home countries when the institutional costs from the home countries’ institutions that diminish firms’ competitive advantages exceed institutional benefits that enhance firms’ competitive advantages (Luo & Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007). Such avoidance would be referred to as misalignment avoidance. Misalignment would be found in the institutions of emerging economies that often accompany institutional voids and hazards and, accordingly, erode the competitiveness of firms (De Soto, 2000; Sun et al., 2015). The underdeveloped institutions of the home country, departing from global standards, may compel MNEs to escape the home country in order to avoid the competitive disadvantages. In this respect, the institutions of developed or advanced economies are considered more business friendly than the institutions of emerging economies (De Soto, 2000; Peng et al., 2008). However, underdeveloped institutions would not be the sole catalyst of institutional misalignment. Misalignment may also be found in advanced institutions when firms in such an institutional environment regard the given institutions as business unfriendly. In this situation, firms may reckon that the institutional costs resulting from the unfriendliness toward business would exceed the benefits from the institutions. Thus, they may endeavor to avoid certain home-country-based institutions by undertaking FDI (Fung, Yau & Zhang, 2011; Hoskisson et al., 2013).

An example of misalignment in the advanced institutions of developed economies may be corporate tax. Corporate tax is a typical example of firms’ institutional costs, levied by the tax regime of the country where the firm operates. Tax is the final line in assessing firms’ net income and, accordingly, exerts a direct influence on profitability. Thus, firms endeavor to maximize tax efficiency—in other words, to maximize the after-tax cash flow (Scholes et al., 2002). Going forward, tax is one of the primary determinants of firms’ capital structure (Heider & Ljungqvist, 2015). When firms have greater pre-tax income, they would be more inclined than other firms with smaller pre-tax income to undertake tax planning (Mills, Erickson & Maydew, 1998; Phillips, 2003). Specifically, MNEs that harvest profits from overseas markets may need to repatriate such foreign profits to their home countries. However, additional tax imposed by the home country tax regime on repatriated foreign profits may encourage these MNEs to look for ways to save such additional tax, by investing in lower tax locations.

p.415

DMNEs may be more concerned with tax than EMNEs, given that corporate tax rates of developed economies are generally higher than those of emerging economies.2 However, EMNEs may also be concerned with tax if a jurisdiction offers lower tax than the home country of EMNEs. Accordingly, many DMNEs and EMNEs engage in institution shopping by taking advantage of low-tax institutions offered by countries around the world, especially tax havens—jurisdictions that offer lower tax to firms that have business domicile there (Desai, Foley & Hines, 2006). According to Hines (2010), more than 50 countries and territories are commonly considered to be tax havens (see Table 24.1).

While some low-tax jurisdictions with poor governance structures may not attract FDI, tax havens tend to be relatively small and affluent countries that also have good governance structures (Dharmapala & Hines, 2009). Those friendly tax and corporate laws of tax havens may present strategic value to MNEs with respect to performance enhancement, because shareholders and managers usually prefer the reduction of tax payments in order to maximize the after-tax cash flow (Cary, 1974; Scholes et al., 2002).

As a result, MNEs have increased their FDI into tax havens. While the economic size of tax havens is minimal in the world economy,3 the FDI into tax havens is significant. As shown in Table 24.2, tax havens hold approximately 20% of total FDI flows in the world, reaching approximately $300 billion (UNCTAD, 2015). This scale of tax havens in worldwide FDI supports empirical studies hypothesizing and finding that US firms operating in at least one tax haven carry less worldwide tax burden than firms with no operations in tax havens (Graham & Tucker, 2006; Dyreng & Lindsey, 2009).

Table 24.2 Recent five-year trend of FDI in tax havens (billion USD)

Source: Authors’ construction from UNCTAD (2015).

p.416

To mitigate institutional costs, tax havens have become satisfactory destinations for institution shoppers interested in lower taxes. Now many developed economies stipulate a black list of tax havens and strictly regulate the native MNEs of developed economies so as not to circumvent the higher corporate tax rates of home countries. However, MNEs keep on endeavoring to find legitimate ways to avoid tax in order to mitigate their institutional costs.

A typical example to leverage a tax haven would be tax inversion, a corporate practice to acquire a foreign firm and place the headquarters in the home country of the acquired foreign firm in order to avoid tax (Voget, 2011). However, tax inversion among US firms has occurred only twice between 1983 and 1994, the next decade (1994 to 2004) witnessed 27 incidents, and the latest decade (2004 to 2014) found 44 cases of corporate inversion (Washington Post, 2014). Although the US Treasury Department promulgated regulations in order to “stamp out the practice”, America’s tax policy imposing one of the highest corporate tax rates in the developed economies would not completely remove US MNEs’ interest in tax inversion (Economist, 2015a). Earlier cases of tax inversion were involved with tax havens, and recent tax inversions have occurred in some low-tax countries, even developed economies such as Canada, that are not typically considered as a tax haven but which offers lower tax than the home country.

Case: Endo Health Solutions and Medtronic. In 2013, a US-based pharmaceutical firm Endo Health Solutions acquired a Canada-based pharmaceutic company Paladin Labs for $1.6 billion. In so doing, Endo Health Solutions created a holding company in Ireland as its new corporate headquarters. In 2014, the world’s largest stand-alone medical device company Medtronic acquired an Irish health care producer Covidien for $42.9 billion. Upon the completion of the acquisition, Medtronic moved its headquarters from the US to Ireland in order to enjoy the 10% corporate tax rate offered by Ireland to domestic manufacturers.

The commonality in the acquisition cases related to both Endo Health Solutions and Medtronic is that the new venue of the headquarters was Ireland. As a member of the OECD, Ireland maintains a legal infrastructure that is similar to that of the UK and the US, and has endeavored to lure global high-tech and pharmaceuticals, in order to serve as a biotech hub (Financial Times, 2014). In this regard, Ireland offers a 10% corporate tax rate to the manufacturers legally domiciled in this country. Such a low tax rate is enjoyed by companies that are tax residents of Ireland, including Endo Health Solutions and Medtronic. Furthermore, such companies frequently engage in high royalty payments from Irish headquarters to subsidiaries located in other tax havens with lower tax rates, and thus minimize tax payments in Ireland as well as in their home countries by not repatriating any profits (Fuest et al., 2013).

Case: Burger King. Burger King, a US-based fast-food chain, acquired Tim Hortons, a Canadian coffee-and-doughnuts franchise, for $11.4 billion in December 2014. This acquisition boosted Burger King to become the world’s third largest chain in the fast food industry. However, the alleged hidden motive of Burger King with respect to this acquisition might include avoidance of US taxes by removing its post-merger headquarters to Canada.4 As a result, Burger King’s acquisition of Tim Hortons is regarded as a tax inversion move. By making the move, Burger King successfully circumvented regulatory enforcement of heavier tax burden of the United States. That is, by the acquisition, shareholders of Burger King may opt for either stock of the resulting company or units of the newly-formed limited partnership in Canada. When a shareholder chooses to receive stock of the partnership, capital gains from such stock are out of the scope of US Treasury rule (Holtzblatt, Jermakowicz & Epstein, 2015).

p.417

Loophole leverage

The global operations of MNEs involve multiple institutions, including home and host countries (Stevens, Xie & Peng, 2016). The entanglement of institutions of countries frequently creates loopholes in regulating the operations of MNEs, because institutions are heterogeneous across countries. MNEs would shop institutions that create such loopholes and provide opportunities to leverage the loopholes—in other words, opportunities of effective use, enjoyment, and disposal of the MNEs’ own tangible or intangible assets. Overall, MNEs undertake FDI for institutional benefits because such benefits may not be available in their home country or principal venue of business. Among various FDI for the sake of loophole leverage, we want to focus on transfer pricing and capital round-tripping.

Transfer pricing. Transfer pricing refers to “the pricing of cross-border intrafirm transactions between related parties” (Eden, 2001, p. 591). In other words, transfer pricing is moving profit around the world by pricing goods or services in the inter-subsidiary transactions to minimize profits in higher-taxed subsidiaries and to maximize profits in lower-taxed ones. Transfer pricing has critical strategic value for MNEs with evidence of positive relations with better performance of MNEs (Cravens, 1997). By engaging in transfer pricing, MNEs exploit arbitrage in different tax rates across countries.5

Such arbitrage usually results in a redistribution of tax revenues among countries and may curtail legitimate tax revenues from countries with higher tax rates (Borkowski, 1997; Slemrod & Kopczuk, 2002). Thus, on the one hand, countries including OECD members are cooperating to prevent transfer pricing practices (OECD Observer, 2011). However, on the other hand, countries also compete to “bid for firms” by levying lower tax in order to attract inward FDI (Black & Hoyt, 1989; Wilson, 1999). Such tax competition is the competition among countries for more supportive tax rates for the purposes of tax base enlargement (Edwards & Keen, 1996). Tax competition may be an effective strategy for a country to attract inward FDI as long as the revenue increase from the enlargement of the tax base from inward FDI outweighs the revenue decrease from tax cuts. In particular, smaller economies with a smaller tax base may enjoy the net increase in tax revenue from the enlarged tax base contributed by attracting foreign capital at the expense of the decrease in the cut in tax rates (Dehejia & Genschel, 1999). Thus, some developing countries may have stronger incentives to attract inward FDI through tax cuts than developed economies (McGee, 2010). Furthermore, developing countries with a smaller economy may resist the tax cooperation to ward off transfer pricing in their economic community.

Accordingly, tax competition may depart from the risk of a tax-cutting war among countries (Mendoza & Tesar, 2005). Going forward, heterogeneous interest across developing and developed countries may permit tax competition without the self-defeat of tax-cutting jurisdictions. Supportive evidence finds that the effective corporate tax rates of 16 countries in the European Union (EU) and G7 have decreased in the 1980s and the 1990s. But tax revenues have not decreased over the same period and have even increased in some small countries (Devereux, Griffith & Klemm, 2002).

This inconsistency in the corporate taxation policy across countries creates loopholes—structural ineffectiveness in regulating transfer pricing. These loopholes motivate MNEs to continue their shopping of institutions and leverage such regulatory loopholes by FDI (Economist, 2015b). That is, MNEs may undertake FDI in high- or low-tax jurisdictions, and transfer profits back and forth between subsidiaries with high- and low-tax jurisdictions.

Case: US MNEs in the UK. Starbucks UK officially recorded its sales of $640 million in 2012, but did not pay any tax to the UK tax authority. No tax payment with such a huge size of revenue could be attributed to, among others, the inter-subsidiary transactions with sister subsidiaries such as the royalty payment to Starbucks Netherlands and the payment for the purchase of coffee beans from Starbucks Switzerland. In a similar vein, in 2011, Amazon UK paid just $3 million in taxes with sales of $5.36 billion and Google UK paid only $9.6 million with $632 million sales (BBC News Magazine, 2013).

p.418

Capital round-tripping. Capital round-tripping means investing abroad and re-investing back into the home country (Fung, Yau & Zhang, 2011). This phenomenon is frequently involved with capital flight from and its return to emerging economies, because many emerging economies, in an effort to attract inward FDI, provide more preferential treatments for foreign firms than for domestic firms, such as tax incentives (Huang, 2003; Peng, 2012; Borga, 2016). Such preferential treatments for foreign firms often encourage domestic firms to obtain the status of “foreign firms” by investing abroad and becoming foreign firms (Luo & Tung, 2007; Peng, 2012). The round-tripped capital is legally treated as foreign investment, even though the origin of such capital is the original home country of such originally domestic (and now foreign) firms. Thus, MNEs from such emerging economies are likely to leverage the loophole for the purposes of obtaining preferential treatments that may not be available to other domestic firms staying in the home country without the round-tripping of capital.

Case: Outward and inward FDI of BRIC. Capital round-tripping is extensively found in FDI from and to BRIC. First, the largest recipient countries of the FDI from Brazil, Russia, India, and China are, respectively, the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cyprus, Mauritius, and Hong Kong6 (Peng, 2014b; Peng, Sun & Blevins, 2011). Given that the BVI, Cyprus, Mauritius, and Hong Kong are categorized as tax havens, the outward FDI from BRIC to these four recipients seems to be motivated, at least in part, by considerations for minimizing corporate tax. Second, what is also interesting is that the BVI, Cyprus, Mauritius, and Hong Kong7 are also, respectively, the largest originating countries of the inward FDI to Brazil, Russia, India, and China8 (Peng, Sun & Blevins, 2011; Peng, 2014b). It seems plausible that many BRIC-based firms have engaged in capital round-tripping, not only for the purposes of maximizing the institutional benefits offered by tax havens, but also attaining the status of “foreign firms” back home in an effort to circumvent the unfriendly institutions of home countries.

Discussion

FDI is one of the most extensively researched topics in IB. But its motives are not entirely explored, particularly when it comes to the participant increase and the spatial expansion of FDI (UNCTAD, 2009, 2015). FDI researchers have introduced asset-based and institution-based perspectives in explaining the motives of FDI (Dunning, 1988, 1993; Mathews, 2006; Luo & Tung, 2007; Witt & Lewin, 2007). However, the literature sheds less light on MNEs’ motives for FDI to seek specific institutions that offer benefits or mitigate costs of MNEs—a move that we characterize as institution shopping.

In endeavoring to start filling this research void, we make important contributions along at least two facets of the conceptual approach to FDI by introducing the construct of institution shopping. First, we move beyond EMNEs, which are the principal focus of the existing literature on institution-based motives of FDI, by positing that both types of MNEs—EMNEs and DMNEs—may endeavor to maximize their institutional benefits by engaging in institution shopping. Second, as for FDI destinations, we extend the FDI literature into a novel consideration from the institution-based view that institutions may be a “selling point” for a country that could overcome its asset-wise deficiencies by inviting FDI in order to enhance its national wealth (Wilson, 1999). Combining those two, we extend the current discussion of whether specific institutions are developed or underdeveloped. That is, we contend that theoretically more important is whether the institutions provide institutional benefits or costs to MNEs. No matter how developed the institutions are in a country, MNEs may avoid the country when the institutions of that country do not provide institutional benefits. In this vein, we stipulate that there exists a global market of institutions where MNEs buy and FDI destinations sell MNE-friendly institutions that would maximize the net institutional benefits of MNEs. Overall, this chapter extends earlier institution-based research (Meyer & Peng, 2016; Peng, 2012, 2014b; Peng et al., 2005, 2008, 2009) with a sharper focus on institution shopping as an institution-based rationale behind FDI.

p.419

An avenue to future research can be found from the assumption of a global market of institutions. First, competition for friendly institutions may occur among countries that desperately need FDI (World Bank, 2015). As we see tax competition toward lower tax among some developing countries for the sake of inward FDI (Devereux, Griffith & Klemm, 2002), we may expect institutional competition among countries to increase with a bigger scale and wider scope, when more countries come out of isolation, integrate themselves into the global economy, and endeavor to overcome their late-mover disadvantages by institutional change (Peng, 2003). The institutional change by developing countries may provide MNEs with larger loopholes for regulatory arbitrage such as transfer pricing. In response to the loopholes, developed economies such as the OECD member countries would depart from bilateral negotiation to persuade emerging economies out of their loophole-creating institutions. Instead, developed economies may endeavor to build global institutions through not only transnational organizations such as the United Nations, but also supranational markets or states such as the EU in order to control the expected loophole-leveraging behavior of MNEs (Djelic & Quack, 2003).

Second, we probed whether MNEs may actively endeavor to shape the institutions. The traditional literature on institutions in an IB context has focused on the influence of institutions on MNEs (Peng et al., 2008; Greenwood et al., 2011; Meyer & Peng, 2016). But it has not paid close attention to MNEs that “purposely and strategically shape their institutional environment to enhance their competitive advantage” (Marquis & Raynard, 2015). Such active engagement of MNEs in shaping institutions may be worth investigating, given that MNEs may actively explore the likelihood of institutional benefits from the loopholes in the heterogeneous institutions. As a result, such active MNEs may bring changes to existing institutions or may create new institutions by leveraging resources (DiMaggio, 1988; see Battilana, Leca & Boxenbaum, 2009 for a review). Recent research has developed insights on building institutional infrastructure that purports to be business activities, but is currently inadequate or missing (Mair & Marti, 2009; Marquis & Raynard, 2015). We find this research may be extended further, particularly with respect to informal institutions such as corporate social responsibility (Peng et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Why do MNEs undertake FDI? In addition to the asset-based reasoning captured in the conventional FDI literature, we suggest an alternative answer: some MNEs may sometimes be shopping for business-friendly institutions around the world. In the case of tax inversion, the Obama administration has accused this practice of being “unpatriotic” (Economist, 2015a). Such criticisms reflect a fundamental lack of understanding of the institution-based rationale behind FDI. Institutions matter when transactions become costly (North, 1990). When operating in a country becomes costly, firms would look for another country in which operations are less costly. In conclusion, readers of this chapter—as well as ignorant officials from the Obama administration—can benefit from a quote from Adam Smith (1776/1991, p. 520):

p.420

The proprietor of stock is properly a citizen of the world, and is not necessarily attached to any particular country. He would be apt to abandon the country in which he was exposed to a vexatious inquisition . . . and would remove his stock to some other country where he could either carry on his business, or enjoy his fortune more at his ease.

Notes

1 We thank Gary Cook for clear guidance, and Xiaoou Bai, Hanlin Chi, Jihyun Eun, Ayenda Kemp, Dong Shin Kim, Kyun Kim, Ziyuan Liu, Charlotte Reypens, Jason Shay, and Joyce Wang for helpful comments. This research was supported in part by the Jindal Chair and the Jindal School of Management Ph.D. Research Fellowship.

2 The average corporate tax rate (GDP-weighted) of G7 countries is 33.9% and the OECD member countries show an average rate of 31.6% (OECD, 2015). In contrast, the average rate of the emerging economies such as BRIC and South Africa is 27.3% (Pomerleau, 2015).

3 The total GDP of tax havens listed in Table 24.1 amounts to approximately $1.1 trillion (1.7% of world GDP) in 2010, which is comparable to that of New York State (Hines, 2010).

4 Burger King reportedly saved approximately $275 million of US corporate tax the company would have had to pay if they had been US domiciled (Reuters, 2014).

5 Transfer pricing differs from seeking low-tax jurisdiction. Seeking low-tax jurisdiction assumes the permanent change of firm’s principal domicile in order to have a low corporate tax rate, while transfer pricing is moving profit from a low-tax jurisdiction to a high-tax one in order to reduce the overall tax incurred in both low-tax and high-tax jurisdictions.

6 If Hong Kong is regarded as part of China, then the largest foreign recipient of Chinese outward FDI is the BVI (Peng, Sun & Blevins, 2011).

7 In terms of outward FDI from China, the largest foreign originating country of Chinese inward FDI is also the BVI (Peng, Sun & Blevins, 2011).

8 Of course, not all inward FDI (IFDI) into China is driven by institutional shopping. There is substantial IFDI from DMNEs of the Western world, whose behavior can be mostly captured by existing theories such as the OLI framework. As a result, such IFDI is not our focus. Instead, we concentrate on interesting aspects of IFDI that have not been adequately addressed in the existing literature.

References

Barnard, H. (2010) ‘Overcoming the liability of foreignness without strong firm capabilities: The value of market-based resources’, Journal of International Management, 16, pp. 165–176.

Battilana, J., Leca, B. & Boxenbaum, E. (2009) ‘How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship’, Academy of Management Annals, 3, pp. 65–107.

BBC News Magazine (2013) Google, Amazon, Starbucks: The rise of ‘tax shaming’. May 21. www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20560359.

Black, D.A. & Hoyt, W.H. (1989). ‘Bidding for firms’, American Economic Review, 79, pp. 1249–1256.

Boddewyn, J.J. & Brewer, T.L. (1994) ‘International-business political behavior: New theoretical directions’, Academy of Management Review, 19, pp. 119–143.

Borga, M. (2016) ‘Not all foreign direct investment is foreign: The extent of round-tripping’, in Sauvant, K.P. (Ed.), Columbia FDI Perspectives, no. 172. New York: Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment.

Borkowski, S.C. (1997) ‘The transfer pricing concerns of developed and developing countries’, International Journal of Accounting, 32, pp. 321–336.

Cary, W.L. (1974) ‘Federalism and corporate law: Reflections upon Delaware’, Yale Law Journal, 83, pp. 663–705.

p.421

Cravens, K.S. (1997) ‘Examining the role of transfer pricing as a strategy for multinational firms’, International Business Review, 6, pp. 127–145.

Dehejia, V.H. & Genschel, P. (1999) ‘Tax competition in the European Union’, Politics & Society, 27, pp. 403–430.

Denisia, V. (2010) ‘Foreign direct investment theories: An overview of the main FDI theories’, European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2, pp. 104–110.

Desai, M.A., Foley, C. & Hines, J.R. (2006) ‘The demand for tax haven operations’, Journal of Public Economics, 90, pp. 513–531.

De Soto, H. (2000) The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books.

Devereux, M.P., Griffith, R. & Klemm, A. (2002) ‘Corporate income tax reforms and international tax competition’, Economic Policy, 17, pp. 449–495.

Dharmapala, D. & Hines, J.R. (2009) ‘Which countries become tax havens?’ Journal of Public Economics, 93, pp. 1058–1068.

DiMaggio, P.J. (1988) ‘Interest and agency in institutional theory’, in Zucker, L. (Ed.), Institutional Patterns and Organizations. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, pp. 3–22.

Djelic, M.L. & Quack, S. (Eds.) (2003) Globalization and Institutions: Redefining the Rules of the Economic Game. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Dunning, J.H. (1988) ‘The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions’, Journal of International Business Studies, 19, pp. 1–31.

Dunning, J.H. (1993) Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Basingstoke, UK: Addison Wesley.

Dyreng, S.D. & Lindsey, B.P. (2009) ‘Using financial accounting data to examine the effect of foreign operations located in tax havens and other countries on US multinational firms’ tax rates’, Journal of Accounting Research, 47, pp. 1283–1316.

The Economist (2015a) Inverted Logic. August 15. www.economist.com/node/21660978/print.

The Economist (2015b) New Rules, Same Old Paradigm. October 10. www.economist.com/node/21672207/print.

Eden, L. (2001) ‘Taxes, transfer pricing, and the multinational enterprise’, in Rugman, A. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of International Business. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 591–619.

Edwards, J. & Keen, M. (1996) ‘Tax competition and Leviathan’, European Economic Review, 40, pp. 113–134.

Financial Times (2014) Tax Avoidance: The Irish Inversion. April 29. www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/d9b4fd34-ca3f-11e3-8a31-00144feabdc0.html.

Fuest, C., Spengel, C., Finke, K., Heckemeyer, J.H. & Nusser, H. (2013) ‘Profit shifting and “aggressive” tax planning by multinational firms: Issues and options for reform’, World Tax Journal, 4, pp. 307–324.

Fung, H.G., Yau, J. & Zhang, G. (2011) ‘Reported trade figure discrepancy, regulatory arbitrage, and round-tripping: Evidence from the China–Hong Kong trade data’, Journal of International Business Studies, 42, pp. 152–176.

Gammeltoft, P., Barnard, H. & Madhok, A. (2010) ‘Emerging multinationals, emerging theory: Macro-and micro-level perspectives’, Journal of International Management, 16, pp. 95–101.

Graham, J.R. & Tucker, A.L. (2006) ‘Tax shelters and corporate debt policy’, Journal of Financial Economics, 81, pp. 563–594.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E.R. & Lounsbury, M. (2011) ‘Institutional complexity and organizational responses’, Academy of Management Annals, 5, pp. 317–371.

Heider, F. & Ljungqvist, A. (2015) ‘As certain as debt and taxes: Estimating the tax sensitivity of leverage from state tax changes’, Journal of Financial Economics, 118, pp. 684–712.

Hill, C.W. & Hoskisson, R.E. (1987) ‘Strategy and structure in the multiproduct firm’, Academy of Management Review, 12, pp. 331–341.

Hines, J.R. (2010) ‘Treasure islands’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24, pp. 103–126.

Holtzblatt, M., Jermakowicz, E.K. & Epstein, B.J. (2015) ‘Tax heavens: Methods and tactics for corporate profit shifting’, International Tax Journal, 41, pp. 33–44.

Hoskisson, R.E., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I. & Peng, M.W. (2013) ‘Emerging multinationals from mid-range economies: The influence of institutions and factor markets’, Journal of Management Studies, 50, pp. 1295–1321.

Huang, Y. (2003) Selling China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

p.422

Luo, Y. & Tung, R.L. (2007) ‘International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective’, Journal of International Business Studies, 38, pp. 481–498.

Mair, J. & Marti, I. (2009) ‘Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh’, Journal of Business Venturing, 24, pp. 419–435.

Makino, S., Lau, C.M. & Yeh, R.S. (2002) ‘Asset-exploitation versus asset-seeking: Implications for location choice of foreign direct investment from newly industrialized economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, 33, pp. 403–421.

Marquis, C. & Raynard, M. (2015) ‘Institutional strategies in emerging markets’, Academy of Management Annals, 9, pp. 291–335.

Mathews, J.A. (2006) ‘Dragon multinationals: New players in 21st century globalization’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23, pp. 5–27.

McGee, R.W. (2010) ‘Ethical issues in transfer pricing’, Manchester Journal of International Economic Law, 7, pp. 24–41.

Mendoza, E.G. & Tesar, L.L. (2005) ‘Why hasn’t tax competition triggered a race to the bottom? Some quantitative lessons from the EU’, Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, pp. 163–204.

Meyer, K.E. & Peng, M.W. (2016) ‘Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research’, Journal of International Business Studies, 47, pp. 3–22.

Mills, L., Erickson, M.M. & Maydew, E.L. (1998) ‘Investments in tax planning’, Journal of the American Taxation Association, 20, pp. 1–20.

North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

OECD (2015) Revenue Statistics 2015. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD Observer (2011) Multinational Enterprises: Better Guidelines for Better Lives. July 28. www.oecdobserver.org/news/fullstory.php/aid/3553/Multinational_enterprises:_Better_guidelines_for_better_lives.html.

Peng, M.W. (2003) ‘Institutional transitions and strategic choices’, Academy of Management Review, 28, pp. 275–296.

Peng, M.W. (2012) ‘The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China’, Global Strategy Journal, 2, pp. 97–107.

Peng, M.W. (2014a) Global Business. 3rd edition. Cincinnati, OH: Cengage Learning.

Peng, M.W. (2014b) ‘New directions in the institution-based view’, in Boddewyn, J. (Ed.), International Business Essays by AIB Fellows. Bingley, UK: Emerald, pp. 59–78.

Peng, M.W., Lee, S.-H. & Wang, D.Y. (2005) ‘What determines the scope of the firm over time? A focus on institutional relatedness’, Academy of Management Review, 30, pp. 622–633.

Peng, M.W. & Luo, Y. (2000) ‘Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link’, Academy of Management Journal, 43, pp. 486–501.

Peng, M.W., Sun, S.L. & Blevins, D.P. (2011) ‘The social responsibility of International Business scholars’, Multinational Business Review, 19, pp. 106–119.

Peng, M.W., Sun, S.L., Pinkham, B. & Chen, H. (2009) ‘The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod’, Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, pp. 63–81.

Peng, M.W., Wang, D.Y. & Jiang, Y. (2008) ‘An institution-based view of International Business strategy: A focus on emerging economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, 39, pp. 920–936.

Phillips, J.D. (2003) ‘Corporate tax-planning effectiveness: The role of compensation-based incentives’, Accounting Review, 78, pp. 847–874.

Pomerleau, K. (2015) ‘Corporate income tax rates around the world, 2015’, in Tax Foundation (Ed.), Fiscal Fact, no. 483. Washington, DC: Tax Foundation.

Reuters (2014) Burger King to Save Millions in U.S. Taxes in ‘Inversion’: Study. December 11. www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/11/us-usa-tax-burgerking-idUSKBN0JP0CI20141211.

Scholes, M., Wolfson, M., Erickson, M., Maydew, E. & Shevlin, T. (2002) Taxes and Business Strategy: A Planning Approach. 3rd Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Slemrod, J. & Kopczuk, W. (2002) ‘The optimal elasticity of taxable income’, Journal of Public Economics, 84, pp. 91–112.

Smith, A. (1776/1991) The Wealth of Nations. New York: Prometheus Books.

Stevens, C., Xie, E. & Peng, M.W. (2016) ‘Toward a legitimacy-based view of political risk: The case of Google and Yahoo in China’, Strategic Management Journal, 37, pp. 945–963.

Sun, S.L., Peng, M.W., Lee, R.P. & Tan, W. (2015) ‘Institutional open access at home and outward internationalization’, Journal of World Business, 50, pp. 234–246.

p.423

Sun, S.L., Peng, M.W., Ren, B. & Yan, D. (2012) ‘A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M&As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs’, Journal of World Business, 47, pp. 4–16.

UNCTAD (2009) World Investment Report: Transnational Corporations, Agricultural Production and Development. New York and Gueneva: United Nations. http://unctad.org/en/docs/wir2009_en.pdf.

UNCTAD (2015) FDI Inflows, by Region and Economy, 1990–2014. New York and Gueneva: United Nations. http://unctad.org/en/Pages/DIAE/World%20Investment%20Report/Annex-Tables.aspx.

Voget, J. (2011) ‘Relocation of headquarters and international taxation’, Journal of Public Economics, 95, pp. 1067–1081.

Washington Post (2014) These Are the Companies Abandoning the U.S. to Dodge Taxes. August 6. www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonkblog/wp/2014/08/06/these-are-the-companies-abandoning-the-u-s-to-dodge-taxes/.

Wilson, J.D. (1999) ‘Theory of tax competition’, National Tax Journal, 52, pp. 269–304.

Witt, M.A. & Lewin, A.Y. (2007) ‘Outward foreign direct investment as escape response to home country institutional constraints’, Journal of Studies, 38, pp. 579–594.

World Bank (2015) Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency. Washington, DC: World Bank. www.doingbusiness.org/~/media/GIAWB/Doing%20Business/Documents/Annual-Reports/English/DB16-Full-Report.pdf.

Xia, J., Ma, X., Lu, J.W. & Yiu, D.W. (2014) ‘Outward foreign direct investment by emerging market firms: A resource dependence logic’, Strategic Management Journal, 35, pp. 1343–1363.

Zahra, S.A., Ireland, R.D. & Hitt, M.A. (2000) ‘International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance’, Academy of Management Journal, 43, pp. 925–950.