Chapter 5

Cost Estimating and Bidding

5.1 Introduction

Cost estimating is a function that is central and indispensable for every construction contracting business. Estimating can be defined as the estimator's making the best possible prediction of what the cost of performing a construction project will be, given the time and other resources available. Construction estimating involves the determination and analysis of the many factors that influence and contribute to the cost of a construction project. Estimating, which is done prior to the physical performance of the work, requires detailed study of the bidding documents, as well as a careful analysis of numerous factors that will have a bearing on construction costs. Estimators apply their knowledge and skills, carefully analyze the construction documents, and examine as many other factors and influences as they can foresee, and then, through the application of their skills, produce this prediction—the cost estimate.

5.2 General

Construction cost estimates are prepared for a variety of purposes, and much of the credit for the success or failure of a contracting enterprise can be ascribed to the skill and astuteness, or the lack thereof, of its estimating staff. If the contracting firm obtains its work by competitive bidding, the company must be the low bidder on a sufficient number of the projects it bids if it wishes to stay in business. However, the construction projects the firm obtains must not be priced and bid so low that the company cannot realize a reasonable profit from their performance. In an atmosphere of intense competition, the preparation of realistic bids requires the utmost in good judgment and estimating skill.

Although negotiated contracts frequently lack the intensity of the competitive element inherent in competitive bid contracting, the accurate estimating of construction costs nonetheless constitutes an important aspect of these contracts as well. In this environment, the contractor is expected to provide the owner with reliable advance cost information, and the contractor's ability to do so determines in large measure its continuing ability to attract owner-clients and to be able to enter contracts with them for the performance of their construction projects. In design-construct and construction management contracts, the contractor and the construction manager are called upon to provide expert advice and assistance with determining construction cost as the design is developed. The advance estimation of costs is a necessary part of any construction operation and is a key element in the conduct of a successful construction contracting business.

It must be understood that construction estimating bears little resemblance to the compilation of industrial “standard costs.” By virtue of standardized conditions and close plant control, a manufacturing enterprise can predetermine the total cost of a unit of production in an almost exact way. Construction estimating, by comparison, involves determining prices for an environment that is far more variable. The absence of any appreciable standardization of conditions from one project to the next, coupled with the inherently complicating factors of weather, materials, labor, transportation, locale, and a myriad of others, makes the advance computation of exact construction costs a matter much more complex than in a more controlled environment. Nevertheless, on the whole, construction estimators do a remarkably good job, despite the numerous variables of all kinds with which they are confronted on almost every project.

While the fundamentals of the estimating process are consistent and do not change, it should also be recognized that every estimator has his or her own unique approach to the estimating process, as well as his or her own subtle variations in procedure. In addition, the policies and procedures of the construction company or of its estimating department, will determine some aspects regarding the preparation of the estimate. It has been said, therefore, that estimating is partly an art and partly a science.

There are probably as many different estimating procedures as there are contractors. In any process involving such a large number of intricate determinations, innovations and variations will naturally result. The form of the worksheets, the order of procedure, and the mode of applying costs all are subject to considerable diversity, with procedures being developed and molded by the individual estimator and the individual construction company to suit their own needs. However, in a move designed to eventually introduce a measure of uniformity to construction estimating, two national trade groups representing estimators have agreed to produce a set of uniform standards for the practice of construction estimating. The American Society of Professional Estimators (ASPE), representing estimators who work for contractors, and the American Association of Cost Engineers (AACE), made of up estimators working for large industrial owners, have agreed to a joint effort in this regard.

It should also be noted that computer hardware and software play an indispensable role in the estimation of construction costs in construction professional practice today and that there are numerous different elements of hardware and software in widespread usage by contractors. However, the basic component elements of producing an estimate are the same; different computer applications simply manage the data in different ways. This chapter presents and discusses primarily the fundamentals of estimating terminology and procedure. Computer applications of the estimating process are discussed later in the chapter.

5.3 Types of Estimates

Estimates are prepared by contractors for different purposes, and in response to different needs of architect-engineers, developers, and owners. These different types of estimates likewise produce different degrees of accuracy in their prediction of construction costs.

5.3.1 Approximate Estimates

For a variety of reasons, a contractor may need to determine an approximate estimate, which is also referred to as a conceptual cost estimate. These estimates are usually needed and usually produced within a short period of time. By definition, they do not provide the same amount of accuracy as a detailed estimate, but are generally order-of-magnitude estimates. Estimates of this kind are also referred to as factor estimates or as parametric estimates.

An owner or a developer may need an approximate estimate as part of a feasibility study, or as a prelude to arranging project financing. Negotiated contracts with owners are sometimes entered while the drawings and specifications are still in development, often beginning at a rudimentary stage. In such a case, the contractor is frequently asked to compute an approximate target estimate for the owner by some approximation procedure.

Sometimes it may be desirable to make a quick and independent check of a detailed cost estimate. The general contractor may wish to compute an approximate cost of a specialty item of work usually subcontracted, either to serve as a preliminary component within its bid or perhaps to provide a check on quotations already received from subcontractors.

The preparation of preliminary estimates is an art quite different from the making of a detailed estimate of construction cost. Fundamentally, all approximate cost estimates are based on some system of unit costs, which are obtained from historical records of previous construction work. The original costs are converted to unit prices and extrapolated forward in time to reflect current prices, with additional adjustments made in an effort to reflect current market conditions and the peculiar character of the project currently under consideration. The level of experience and acquired knowledge base of the estimator will also play an important role in the formulation of approximate estimates.

Some of the methods commonly used to prepare approximate estimates are:

- Square-foot cost estimate. An approximate cost obtained by using an estimated price for each square foot of gross floor area, or perhaps cost per square foot of air conditioned space or in some cases, square feet under roof. Square foot estimates can also be used for items such as number of square feet of sod in place, or asphalt paving, or of concrete flatwork, etc.

- Cubic-foot cost estimate. An estimate based on an approximated cost for each cubic foot of the total volume enclosed, or perhaps per cubic foot of air conditioned space.

- Cost-per-function estimate. An analysis based on the estimated cost per item of use, such as cost per patient in a hospital, cost per student or per seat in a school, cost per vehicle space for a parking facility, or cost per unit of production in a manufacturing environment.

- Modular takeoff estimate. An analysis based on the estimated cost of a representative module, such as a hospital room or college dormitory room, this cost then being extrapolated to the entire structure, plus the estimator's assessment of the cost of common central systems such as heating, ventilating, and air conditioning systems; elevators; and so on.

- Partial takeoff estimate. An analysis using quantities of composite work items that are priced using estimated unit costs. Preliminary costs of projects can be computed on the basis of making estimates of the probable costs of concrete in place, per cubic yard; structural steel erected, per ton; excavation, per bank cubic yard; hot-mix asphalt paving in place, per ton; and the like.

- Panel unit cost estimate. An analysis based on assumed unit costs per square foot of floors, perimeter walls, partition walls, ceilings, and roof.

- Parameter cost estimate. An estimate involving unit costs, called parameter costs, for each of several different building components or systems. The costs of site work; foundations; floors; exterior walls; interior walls; structure; roof; doors; glazed openings; plumbing; heating, ventilating, and air conditioning equipment; electrical work; and other items are determined separately by the use of estimated parameter costs. These unit costs can be based on dimensions or quantities of the components themselves or on the common measure of building square footage.

The unit prices used in conjunction with these approximate estimates can be extremely variable, depending upon specific requirements, geographical location, weather, labor productivity, season, transportation, site conditions, and other factors. There are many sources of such cost information in books, journals, magazines, and the general trade literature. Unit costs are also available commercially from a variety of proprietary sources, as well as from the contractor's own past experience. In addition, there are many forms of national price indexes that are useful in updating cost information of past construction projects. When such costs or cost indexes are used, care must be taken that the information is adjusted as accurately as possible so as to conform to local and current project conditions.

Contractors who prepare approximate estimates will apply their judgment and skill in determining which source or sources of information are best to be utilized. Where possible, most contractors will base such estimates on their own historical cost information, a topic that will be discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter.

5.3.2 Detailed Estimates

Detailed estimates are the most accurate and reliable form of estimates of what future construction costs will be. They require that complete drawings and specifications describing the work be available. Detailed estimates are much more costly and time consuming to prepare than approximate estimates.

A detailed estimate of project cost is what the contractor will normally compile for bidding or negotiation purposes whenever an estimate that is to culminate in a proposal is required. Detailed estimates are also usually employed by subcontractors in the preparation of the quotation prices, or proposal prices, which they submit to prime contractors. Detailed estimates are also used while a project is under way, for the pricing of changes in the work.

5.3.3 Lump-Sum Estimates

Two forms of detailed estimates are widely used in the construction industry. These are the lump-sum estimate and the unit-price estimate. Cost estimates in the field of building construction are customarily prepared on a lump-sum basis. Under this procedure, a fixed price is compiled, and if a contract is entered, the contractor agrees to perform a prescribed package of work in full accordance with the drawings and specifications and the other elements of the contract documents for the lump-sum price that was derived from the estimate and will be written into the agreement as the contract price. The contractor agrees to carry out its responsibilities so as to fully comply with all of the elements of the contract documents, even though the cost may prove to be greater than the stipulated amount, and therefore he is said to be at risk for the contract amount that was derived from the detailed estimate.

Lump-sum estimates are applicable only when the exact nature of the work and the quantities involved are well defined by the bidding documents. From the owner's standpoint, such a contract can have many advantages. For example, the contract amount fixes the total project cost, a condition that can be useful when the owner is making the financial arrangements for the project. Additionally, if the drawings and specifications clearly describe the work and therefore define exactly what it is that the owner will receive, then the lump sum competitive bid method of contracting places contractors and subcontractors in competition with one another for the award of the contract, thus yielding the lowest construction cost for the owner.

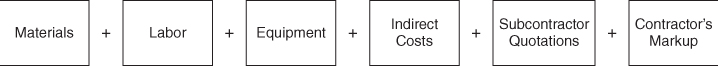

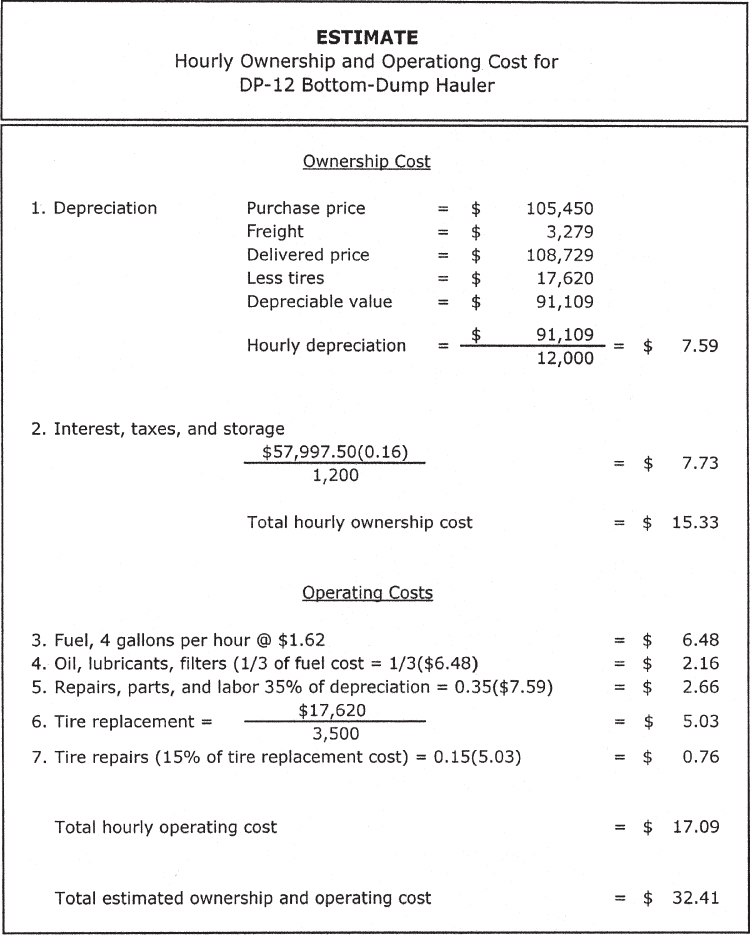

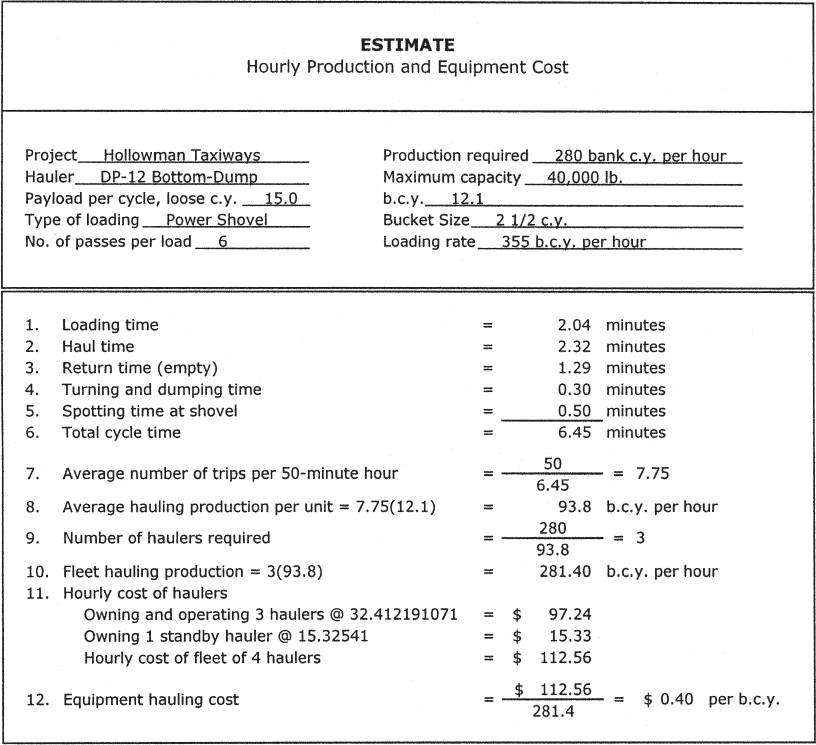

A prime contractor's detailed lump-sum estimate consists of six components: materials, labor, equipment, indirect cost, subcontractor quotations, and markup. The estimator will make a determination of his best prediction of the project cost for each of the first five components, and then will determine and enter a markup amount. The lump-sum cost estimate, that is, the amount to be entered onto the proposal, will be the total of these six components of the estimate. Figure 5.1 illustrates this process in graphic form.

Figure 5.1 Components of a Detailed Lump-Sum Estimate

When a prime contractor is preparing a lump-sum proposal, he will typically require the subcontractors to submit lump-sum proposals for their specialty items of work. Subcontractors will use the same procedure in determining the amount of their proposal. For a subcontractor, the estimate will consist of five components (unless the subcontractor plans to sub-subcontract a portion of the work), which are totaled in order to arrive at the lump-sum amount of their proposal.

Lump-sum estimating requires that a “quantity survey” or “quantity takeoff” be made. This is a complete listing of all the materials and items of work that will be required. Using these work quantities as a basis, the contractor computes the costs of the materials, labor, equipment, indirect cost, and subcontracts. The sum total of these individual items of cost constitutes the anticipated overall cost of the construction. Addition of a markup yields the lump-sum estimate that the contractor submits to the owner as its price for doing the work. The quantity takeoff process will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent sections of this chapter.

5.3.4 Unit-Price Estimates

Engineering construction projects are generally bid, not on a lump-sum basis, but rather as a series of unit prices, and the contract that is awarded is a unit-price contract. In engineering projects where the unit-price method of contracting is commonly employed, often quantities of the materials and the actual amount of the work activities cannot be determined in advance of contract formation with sufficient accuracy to permit the use of lump-sum contracts. Therefore, the estimate is based on the contractor's unit prices, dollars per unit of quantity, for named activities and items of work as defined by the architect-engineer, and in an approximate quantity estimated by the architect-engineer during the design. A unit-price contract is formed, with the contract stipulating that each of the activities and work items to be performed will be completed by the contractor in such a way as to fulfill all of the requirements of the contract documents, at the unit prices that have been set forth in the contractor's proposal.

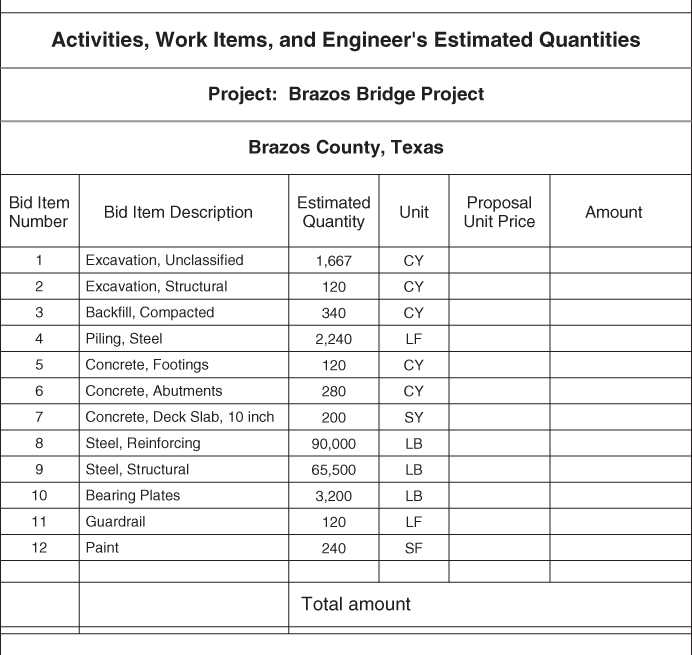

The bidding schedule in Figure 5.2 shows a typical list of unit price activities or work items, which become bid items in a unit price proposal. An estimated quantity is shown for each item. As was noted earlier, these quantity estimates are those made by the architect-engineer as the design is produced and are not guaranteed to be accurate.

Figure 5.2 Unit-Price Bid Items

When unit-price proposals are involved, a somewhat different estimating procedure from that described in the previous section must be followed. A quantity survey is made, much as for a lump-sum estimate, but in this method a separate survey is needed for each bid item. This survey not only serves as a basis for computing costs but also checks the accuracy of the architect-engineer's estimated quantities. A total project cost, including labor, equipment, materials, subcontracts, indirect cost, and markup is compiled, just as in the case of a lump-sum estimate. However, in this method, all costs are kept segregated according to the individual bid item to which they apply. More information on this process is presented in sections that follow in this chapter.

When computing unit prices, the contractor must keep several important factors in mind. The quantities, as listed in the schedule of bid items, are estimates only. The contractor will be required to complete the work specified, in accordance with the contract documents, and will be paid on the basis of the quoted unit prices, whether quantities are greater than or smaller than the designer's estimated amounts.

Sometimes this requirement is modified by provisions in the contract that provide for an equitable adjustment of a unit price when the actual quantity of an activity or work item on the proposal varies more than a stipulated percentage above or below the quantity first estimated by the architect-engineer. Values of 15 to 25 percent are often used in this regard.

In unit-price contracting, all items of material, labor, supplies, or equipment that are not specifically enumerated for payment as separate items, but are reasonably required to complete the work as shown on the drawings and as described in the specifications, are considered as subsidiary obligations of the contractor. No separate measurement or payment is made for these items. Rather, the owner expects to pay, and the contractor expects to be paid, solely on the basis of the activities and work items set forth in the proposal, and at the unit prices that were proposed, and which then became part of the contract.

5.4 Preliminary Considerations Prior to Commencing the Estimate

General contractors may learn of the existence of a project that has been designed and for which proposals are being sought, through seeing an advertisement for bids, or by receiving an invitation to bid. Additionally, contractors may be contacted by an owner or an architect-engineer to make them aware of the existence of a forthcoming project. Contractors may also learn of the project through one of their professional associations or from a plan room operated by one of these associations.

5.4.1 Reporting Services

Another source of bidding information is the plan service centers that have been established in larger metropolitan areas around the country. These centers publish and distribute, on a regular basis, bulletins that describe all projects, public and private, to be bid in the near future within that locality. In addition, these services keep copies of the bidding documents on file for the use of subscribing general contractors, subcontractors, material dealers, and other interested parties.

These plan centers provide a valuable service in making bidding documents available to a wide circle of potential bidders. Prime contractors use the services as a central source of bidding information, to make a quick check of the bidding documents to determine whether they wish to bid, and as an indication of which subcontractors and material dealers may be bidding a given project.

The use of plan centers for actual estimating purposes is generally limited to those subcontractors and material vendors whose takeoff is not as extensive as that of the general contractor. Sometimes these plan rooms and plan centers allow their member subscribers to check out the contract documents for projects for a limited period of time. Prime contractors who are planning to bid a project will typically obtain contract documents and bid documents directly from the architect-engineer.

On the national level, Dodge Reports, published by the Dodge Division of McGraw-Hill Information Services Company, provide complete coverage of bidding and construction activity within different specified localities. Subscribers receive daily reports concerning jobs to be bid in their area, or a designated area of interest, including all known general contractor bidders. This is valuable information inasmuch as it provides the general contractor with information regarding who his competition is likely to be on a project, and tells subcontractors and material vendors who the bidding prime contractors are. Following each bidding, the subscribers are informed with regard to who the low bidders or apparent low bidders are, and sometimes they provide complete bid tabulations.

The reporting services also will frequently monitor the status of the project regarding whether and when a contract is formed between the owner and prime contractor. During construction, reports are issued periodically listing the general contractor and the subcontractors. Other services are also available from these contractor news services, and subscriptions can be tailored to suit the needs of the contractor.

5.4.2 Availability of Drawings and Specifications

After learning of the existence of a project, the contractor will examine the information in the advertisement for bids or the invitation to bid and will determine whether he is sufficiently interested in the project to procure the bid documents and contract documents. The advertisement or invitation will provide information for general contractors regarding procedures for obtaining contract documents and bid documents for the project from the architect-engineer.

If a general contracting firm has decided it is sufficiently interested in the project to examine the contract and bid documents, it will normally obtain the necessary sets of bidding documents from the architect-engineer or the owner. The number of sets needed will depend on the size and complexity of the project, the time available for the preparation of the bid, and the distribution the architect-engineer has made to subcontractors, material dealers, and plan services. In general, more sets will be required for shorter bidding periods and for more complex projects.

It is typical for architect-engineers to require contractors to pay a deposit for each set of documents they request from the designer, as a safeguard against frivolous ordering, and as a guarantee for the safe return of the documents to the designer. This deposit, which may range from 50 to several hundred dollars per set, is usually refundable. It is not uncommon, however, for the architect-engineer to note that a contractor wishing to receive bid documents and contract documents must pay a fee or a nonrefundable deposit for each set of documents requested. The objective of this practice, which amounts to contractor purchase of the documents, is to help the owner or architect-engineer recoup some of the printing costs involved in making the documents available.

Certainly, the reproduction of these documents by the architect-engineer is costly, and certainly no more sets should be provided by the designer or requested by contractors than are really necessary. However, undue limitation by the architect-engineer or owner with regard to providing the number of sets of bid documents and contract documents needed by all of the potential bidders and plan services can be shortsighted. Any aspect of the bidding process that inhibits competition can only result in a higher cost for the owner. There can be no argument that the architect-engineer providing sufficient numbers of bidding documents to achieve a reasonably thorough coverage of the total bidding community produces the best competitive prices, particularly for large and complex projects. Plan services perform a valuable function in this regard by making drawings and specifications readily available to interested bidders.

For takeoff and pricing purposes, subcontractors and materials dealers can obtain their own bidding documents from the architect-engineer, or they can use the facilities of local plan services. Additionally, it is common practice for the prime contractor to make its own copies of the bid documents and contract documents available to parties wishing to bid on various aspects of the project. Sometimes they allow subcontractors and vendors to check out the documents from the prime contractor's office.

General contractors must be cautious, however, in lending contract and bid documents, and must assure that all bidding and contract documents in their entirety, including addenda that may be issued during the bidding period, are made available. This foresight will eliminate potential difficulties later with subcontractors or material suppliers claiming that they bid on the basis of incomplete information and hence did not tender a complete proposal.

As a matter of professional courtesy, the general contractor frequently will set aside a well-lighted plan room on its own premises for the use of the estimators of subcontractors and material dealers. When such facilities are available, the drawings and specifications need never leave the office of the general contractor and can be made available to a wider range of bidders in an efficient manner.

5.5 Set-Asides

It is possible that when the contractor examines the bid documents and contract documents, he may discover that he is not eligible to bid on certain public projects. This can occur on those projects that have been “set aside” for only those contractors who can satisfy specific criteria. For example, under regulations of the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), certain federal construction projects are set aside specifically for small contractors. In such an instance, a contractor must conform to certain measures of annual business volume in order to be eligible to bid on such a project. In addition, under certain SBA programs, some federal construction contracts are removed entirely from competitive bidding, and contracts are negotiated with socially and economically disadvantaged small business firms (SDBs) as defined by the SBA.

Another example is afforded by public construction work at the federal, state, and local levels that is set aside for disadvantaged business enterprises (DBEs) or minority-owned business enterprises (MBEs). To be eligible to bid such projects, a construction company must be able to provide evidence that it is owned and controlled by minorities, women, or historically disadvantaged groups, and the company meets prescribed certification criteria. There are also some public construction projects that are set aside and reserved for locally based contractors.

5.6 Qualification

Bidder qualification is most often based on experience, competence, and financial criteria, and is entirely separate from set-asides as discussed in the previous section. Many states have enacted statutes that require a general contracting firm wishing to bid on public work in those states, to be qualified before the firm can be issued bidding documents or before it can submit a proposal. Other states require that the contractor's qualifications be judged after it has submitted a proposal. The first method is called prequalification, and the second is called postqualification. Many other public bodies, including agencies of the federal government, require some form of qualification for contractors bidding on their construction projects. While the relative merits and drawbacks of the qualification process are subject to debate, it is a matter of fact that qualification in some form has become almost standard practice in the field of public construction. The obvious purpose served by qualification is to eliminate the incompetent, overextended, underfinanced, and inexperienced contractors from consideration.

Prequalification requirements apply almost universally to highway construction, and in certain jurisdictions all construction projects financed with public funds require contractor prequalification. In those states in which contractors' licenses are required, contractors must be licensed prior to applying for prequalification. To prequalify, the contractors must submit detailed information concerning their experience, equipment, finances, current projects in progress, references, and personnel information, as set forth by the architect-engineer or owner. Evaluation of this information results in a determination as to whether the contractor will be allowed to submit a proposal. Highway contractors usually submit qualification questionnaires at specified intervals and are rated as to their maximum contract capacity. Their construction activities are reflected in their current ratings, with bidding documents being issued only to those who are determined to be qualified to bid on each project. The prequalification certificate may also limit the contractor to bidding on certain types of work, such as grading, concrete paving, or bridge construction.

Although the foregoing description of qualification is centered on publicly financed projects, the same procedures can be and frequently are also utilized on private projects as well. In prequalification and postqualification, the architect-engineer and owner typically request financial information, the contractor's history of past projects performed, names and contact information of owners for whom the contractor has constructed projects, names and qualifications of the contractor's management personnel, and so on. It is increasingly common for the architect-engineer and owner to request information regarding the contractor's safety program, workers' compensation EMR rating, training program, and quality management program as well.

A somewhat different procedure, often used in closed bidding, is for the contractor to submit an individualized qualification summary or portfolio to accompany its proposal. This is essentially a sales document and contains information designed to enhance the contractor's status in the eyes of the owner.

In jurisdictions that require postqualification, the contractor is called upon to furnish certain information as specified by the owner along with its proposal. The information requested has much the same form and content as that required for prequalification, but it serves the qualification purpose only for the particular project being bid.

5.7 The Decision to Bid

After learning that proposals are to be taken on a given construction project, and usually after obtaining and thoroughly studying the bid documents and contract documents, the contractor must make a decision as to whether it is interested in submitting a proposal for the project. The decision is momentous. If the contractor decides not to bid, obviously he has no chance of obtaining a contract award for the project. If the contractor decides to prepare and submit a proposal, he must be prepared to commit to the estimating process, which will result in a proposal.

In a general sense, the “bidding climate” prevailing at the time has a bearing on the contractor's decision to bid or not. The decision to bid involves a study of many interrelated factors, such as his opinion of the owner and the architect-engineer, the nature and size of the project as it relates to company experience and equipment, the amount of work presently on hand, the location of the project, the time of year, the bidding period, the duration of the project, the terms and conditions set forth in the contract documents, the contractor's bonding capacity, the probable competition, labor conditions and skilled labor availability, and so on. It is certainly to a contractor's advantage, and assuredly a good business practice, for the contractor to make as comprehensive and thorough an investigation of all aspects of a project as possible, before the firm expends the considerable time, effort, and money required to compile and submit a proposal. Because it involves such a substantial commitment of resources to prepare a proposal for a project, it goes without saying that once an affirmative decision to bid has been made, the contractor will exert every effort to be the successful bidder.

5.8 The Bidding Period

The bidding period is defined as the time between the announcement of the project and availability of bid and contract documents to the contractors, and the time when proposals are due for submittal to the owner. During the bidding period, the contractor will very carefully examine all of the contract and bid documents, prepare his estimate of the cost of the construction, and prepare his proposal for submittal to the owner and the architect-engineer. The results of his detailed study of the bid and contract documents provide the contractor an overall concept of the total package of work and provide the basis for making the most realistic detailed estimate he can for the price of the construction of the project.

During the bidding period, it is not uncommon for the contractor to find errors, inconsistencies, and missing information in the bidding documents. It is the responsibility of the contractor to bring such imperfections to the attention of the architect-engineer or owner, so that suitable modifications might be made by the responsible party. The contractor will typically submit a number of requests for information (RFIs) to the architect-engineer during this time. The designer will respond, in writing, to each RFI. Sometimes the designer will issue an addendum to provide missing information, clarification, or interpretation of some element of the bid or contract documents. Addenda are more fully defined and described in Chapter 4.

A sufficient allocation of time in the bidding period on the part of the architect-engineer and the owner can be an important consideration. The contractor's estimating process takes considerable time and must be dovetailed into contractors' current operations. Careful study and analysis of the bid and contract documents on the part of the contractor will usually result in lower bid prices, and a more comprehensive and accurate proposal, and thus substantial savings for the owner.

The more complicated and extensive the project, the greater the dividends a reasonable bidding period will pay to the owner. Unless the work is truly of a rush or emergency nature, it is sound economics for the owner to allow sufficient time for the bidding contractors to make a thorough study and examination of the proposed work.

When an insufficient bidding period is allotted, many of the best prices will not have been received by the contractor in time for inclusion in its proposal. In addition, when a short bidding period and unreasonable bidding deadline is imposed, and the contractor does not have time to thoroughly understand and properly estimate all of the components of the work in the project, he will inevitably compensate for his uncertainty and the resultant increase in the amount of risk he perceives by including additional dollars in his estimate.

Additionally, from the contractor's point of view, the owner should avoid setting any day following or preceding a weekend or holiday as the date for receiving bids. Such times impose undue hardships on the contractors and other bidders and greatly restrict the availability of prices and other information. Afternoon hours for proposal submittal deadlines are much preferred. As far as is practicable, a bidding date should not conflict with other construction bid openings.

5.9 Prebid Meetings

During the bidding period, two different types of prebid meeting are commonly conducted. The first is a prebid meeting initiated and conducted by the architect-engineer and the owner. Early in the bidding period, the owner and designer typically meet with the contractors who are planning to submit proposals for the project. Subcontractors and materials suppliers also frequently attend these meetings. The purpose of this prebid meeting is to provide the designer and the owner an opportunity to review the project requirements with those who will be submitting proposals, to emphasize certain aspects of the proposed work, to clarify or explain difficult points, and to answer questions and to provide clarifications for those who are engaged in preparing proposals for the project. This type of meeting can be very beneficial and is especially appropriate when the work will be complex or when it will involve unusual procedures.

Many contractors believe it is desirable to also hold an internal prebid meeting for projects on which they are planning to submit proposals. These meetings are typically attended by the estimators and the persons who will occupy the principal supervisory positions on the project if the bid is successful and a construction contract is awarded. The exchange of information between those who are estimating the costs of the project and those who will perform the work on the project can be extremely beneficial. Such meetings can be used to explore the alternative construction procedures that might result in a competitive advantage and/or to make tentative decisions regarding methods, equipment, personnel, and time schedules. This information can be very beneficial for the estimator, to assist in preparing a more accurate and competitive proposal.

5.10 Work to Be Self-Performed and Work to Be Subcontracted

Prior to beginning preparation of the detailed estimate, the contractor's estimating and management staff will make a determination of which items of work on the project the contractor plans to perform with its own craft labor forces under its own supervision, called self-performed work, and which items of work the contractor will plan to perform with subcontractors. For those items of work the company plans to perform with its own craft labor, the materials, labor, and equipment costs will be estimated by the contractor.

For those items of work the company plans to perform by subcontracting, subcontractors' proposals will be sought, and will be incorporated into the prime contractor's estimate. Each subcontractor's proposal is expected to include the subcontractor's determination of all materials, labor, equipment, indirect costs, and markup necessary to complete its work to satisfy the requirements of the contract documents.

Early in the bidding period, the contractor will usually send bid invitations to all material dealers and subcontractors who are believed to be interested and whose bids would be desirable, as well as to those subcontractors and vendors with whom the general contractor has had a favorable working relationship in the past. The general contractor advises of the project under consideration, the item for which a quotation is requested, the deadline for receipt of proposals by the prime contractor, the place where bids will be accepted, the name of the person to whom a proposal should be directed, the place where bidding documents are available, and any other special information or instructions that may be necessary. Specific reminders concerning the status of addenda, alternates, taxes, and bond requirements are typically included as well.

General contractors typically maintain a file that lists names, addresses, contact information, and other pertinent information regarding material suppliers and subcontractors. These files are maintained both by geographic area and by specialty. Therefore, when a contractor is planning to bid a project and has made the determination regarding which work on the project he will plan to subcontract, he has a ready source of subcontractor information.

5.11 Site Visit

Following his initial examination of the contract and bid documents, the contractor will usually visit the construction site. Information will be gathered concerning a wide variety of site and local conditions. Examples include:

- Project location, and physical address.

- Probable weather conditions and influences the weather may bring.

- Availability of electricity, water, telephone, and other services.

- Access to the site and access considerations at the site.

- Location and proximity of emergency services.

- Local codes, ordinances, and regulations.

- Conditions pertaining to the protection or underpinning of adjacent property.

- Space available for storage and for laydown areas and onsite fabrication.

- Surface topography and drainage.

- Subsurface soil, rock, and water conditions.

- Underground obstructions and services.

- Transportation and freight facilities nearby.

- Conditions affecting the availability, hiring, housing, and per diem expenses for workers.

- Material prices and delivery information from local material dealers.

- Facilities for rental or lease of construction equipment.

- Local subcontractors.

- Demolition and site clearing.

- Facilities for disposal of debris and location.

It is important that an experienced person perform this site inspection, particularly in locations that are remote from or relatively new or unfamiliar to the contractor's organization. The visitor should become familiar with the project requirements in advance of the site visit and should take with him a set of drawings and specifications for reference. It is desirable that the information developed during the site visit be recorded in a signed report or on a form the contractor may have developed for this purpose, which will become permanent reference information for use throughout the preparation of the project estimate.

It is usually helpful to have available a camera, tape recorder, measuring tape, and other aids appropriate to the occasion, perhaps to include items such as an earth auger and hand level. Photographs and sketches should be used to augment the site visit report. It is not uncommon that a follow-up visit be made on very large or important projects, or when the estimator discovers the need for an important fact or verification of some feature of the site.

When access to the site is restricted for some reason, visits to the site may have to be coordinated with other bidding contractors, a representative of the owner and/or the architect-engineer, and the primary sub-bidders. Site conditions where remodeling or renovation work is included can be especially demanding, involving such considerations as use of existing elevators, control of noise and dust, matching existing materials and finishes, and maintenance of existing services and operations. Experience has shown that the advance preparation of a checklist of items to be investigated during the site visit can be extremely valuable.

5.12 Project Time Schedule

Prior to beginning the detailed estimating process, the estimating staff will carefully evaluate the project duration. The duration is defined as the number of days allotted for completion of all of the requirements of the contract documents for the project following signing of the contract, as stated in the contract documents. The project duration is a very important consideration in the estimating process.

In order to predict construction costs, the contractor must prepare at least a preliminary construction schedule, which is the contractor's plan, on a timeline, for completing the requirements of the contract documents within the specified duration. If the project duration permits, the contractor will most likely plan to perform the work on a five-days-per-week, eight-hours-per-day schedule. However, as indicated by the duration and the amount of work to be performed on the project, the contractor may find it necessary to work on weekends and/or to work overtime, and perhaps even to work in consecutive shifts, in order to complete the project on time. These determinations will have a profound effect upon the cost of the construction, and must therefore be reflected in the estimate.

In some cases, the contractor is required to indicate on the proposal form its own time requirement for completing the project. In either case, construction time becomes a contract provision, and failure to complete the project on time is a breach of contract that can subject the contractor to significant damage claims by the owner, or to the necessity of paying liquidated damages to the owner, as is typically included in the contract language. Liquidated damages are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

An approximate construction schedule is also needed for pricing purposes because a number of items of project overhead expense (to be discussed in more detail in a subsequent section of this chapter) are directly related to the duration of the construction period for the project. These are referred to as time-related overhead costs.

In addition, a general schedule of the major segments of the project provides the estimator with valuable information concerning weather conditions to be expected. This provides a basis for decisions regarding equipment and labor productivity, hot and cold weather operations, and other similar considerations.

In cases where the contracting firm believes the stipulated contract time will be inadequate for project completion using normal construction procedures, it may request that the owner and architect-engineer reconsider the duration that they originally established and allow a longer construction period. Otherwise, the feasibility of overtime or multiple-shift work must be investigated.

5.13 Preparing the Estimate

For every construction project to be performed, whether an engineered project or a building construction project, when the contractor prepares a detailed cost estimate, there are six components of cost to be tabulated: materials, labor, equipment, subcontractor proposals, indirect costs, and markup. Although these elements were depicted in Figure 5.1, they are repeated in Figure 5.3 for convenience.

Figure 5.3 Components of a Contractor's Detailed Estimate

5.13.1 Estimating Materials Costs

5.13.1.1 Quantity Takeoff

The estimator's first step in estimating materials is to identify each material that will be required in the performance of the work in constructing the project. For purposes of discussion in this text, the term materials is construed to mean everything that becomes a part of the finished structure. This includes electrical and mechanical items such as elevators, boilers, escalators, air-handling units, and transformers, as well as the more obvious and traditional items such as lumber, structural steel, concrete, and paint.

Identifying the materials that will be necessary for the performance of the work so as to fulfill the requirements of the contract documents will be determined from the estimator's analysis of the drawings and the specifications for the project. Most of the materials that will be required in a building construction project are not called out in the contract documents in the form of a list or a table; rather, the drawings and specifications show and describe what the finished construction product will be. Therefore, the estimator must analyze all of the components of the contract documents in order to identify all of the materials that will be required to construct the project and to fulfill contract requirements.

On most engineered projects, some of the materials are listed in the unit-price bid items. However, the estimator must determine exactly what the characteristics and properties of those materials are required to be, in order to fulfill the requirements of the contract documents. In addition, the estimator must determine what other materials may be necessary to accompany, or to complete, the proper installation of the bid item materials.

When the requisite materials have been identified and listed, the estimator must determine from the contract documents, the quality levels in which the materials must be furnished as set forth in the contract documents. Most of these requirements will be found in the specifications. Many construction materials such as lumber and plywood are available in a number of different grades; others, such as portland cement concrete or asphaltic concrete, have varying compositions and proportions of ingredients; others such as metals, have different metallurgical properties, various levels of strength, or different finishes specified.

The estimator must infer from the description of materials requirements in the specifications, and from information that may be provided on the drawings, all of the pertinent elements of quality for each material that will be necessary for the construction of the project, so that the end product will comply with the requirements of the contract documents.

The estimator's next step will be to determine the quantity of each material that will be required for the project. This step in the estimating process is usually referred to as the quantity takeoff (QTO) or the quantity survey. The amount of each material needed to perform the work must be quantified in the unit of measure in which the material or product is produced and marketed: cubic yards of cast-in-place concrete, sheets of plywood, bank cubic yards of soil to be excavated, and so on.

Some materials such as concrete are quantified by calculation, based on dimensions in the drawings. Other materials, which are of identical kind, size, and description, such as door units, lighting fixtures, windows, and the like, are quantified by counting the number of identical items as indicated in different parts of the project, as shown on the drawings. Such items are referred to as count items in estimating.

Following the quantification of each material in its appropriate unit of measure, the estimator will determine the amount of each material that will actually need to be purchased in order to complete the work. This is called determining a waste allowance or overage allowance. For some materials, such as framing lumber, the estimator must allow for the fact that the stock lengths in which lumber is sold will be cut by the carpenters to the exact lengths required for the work. Thus, more lumber will need to be purchased than the precise quantity that has been calculated as being necessary for the finished product. For other materials, such as electrical switchgear or air-handling units in the mechanical system, the waste or overage factor will be expected to be zero. The amount of waste or overage allowance to be applied will come from the estimator's experience and judgment.

Additionally, for some materials, the contractor must know the stock sizes in which the material is produced and marketed, and then must calculate the quantity that will need to be purchased to complete the work as required, based on those stock sizes and the language in the specifications. For example, carpet is produced and sold in standard rolls that are 12 feet wide. The drawings and/or specifications will frequently indicate where seams may be made in certain rooms, or they may indicate the maximum number of seams allowable in certain rooms. From this information, the estimator must determine the quantity of carpet that will actually need to be purchased in order to complete the work in compliance with the specifications.

It should also be noted that there are some materials for which contractors do not typically determine quantities. In these instances, contractors rely on vendors or fabricators to determine the quantity necessary. Reinforcing steel and structural steel are commonplace illustrations of this practice.

5.13.1.2 Estimators' Quantity Surveys

Although the bid documents for a unit-price project customarily provide contractors with estimated quantities of each bid item, these are approximate quantity determinations only, and the architect-engineer typically assumes no responsibility for their accuracy or completeness. Architect-engineers' quantities are sometimes computed only within so-called paylines, and may not be representative of work quantities that must actually be done to accomplish the bid item. In addition, more detail is usually required for accurate pricing of the work. Consequently, contractors customarily make their own quantity takeoffs, even on projects for which estimated quantities are given.

In making quantity surveys, the estimator must be able to visualize how the work will actually be accomplished in the field, given the description of the activity or work item on the unit-price proposal form. Correspondingly, many contractors believe that some appropriate on-the-job experience is a necessary prequalification, or at least a significant advantage, for construction estimators.

The quantity survey provides the contractor with valuable information during the construction period, as well as for the initial estimation of project cost. For example, it can provide the contractor with data concerning time that will be required in the field for work accomplishment, crew sizes, and equipment needs. The quantity survey provides purchasing information as well, and serves as a reference for various aspects of the field work as it progresses. Additionally, it is often useful in providing the owner with a variety of costs pertaining to the work.

5.13.1.3 Professional Quantity Surveyors

There are a number of proprietary firms whose principal business is making quantity surveys and cost estimates of selected construction projects. Such firms provide these services on a fee basis. This may be done after the design of the project has been completed, or the firm may act as a cost adviser to the owner and architect-engineer during the design stage. The services of such companies are engaged mostly by owners and architect-engineers as a means of monitoring costs during design so as to keep project costs within budgets and to get the most for the owner's construction dollar. Companies engaged in this form of business are commonly called quantity surveyors.

It has long been standard practice in the United States for bidding contractors to make their own quantity takeoffs. This results in considerable duplication of effort since the owner and architect-engineer may already have determined materials quantities to meet their needs during the evolution of the design. Nevertheless, contractors seldom utilize the services of professional quantity surveyors for purposes of preparing proposals. Contractors prefer to prepare their own quantity surveys, in which they have a sense of confidence. They maintain a staff of experienced estimators whose reliability and accuracy have been well established. During the takeoff process, the estimator must make many decisions concerning procedure, equipment, sequence of operations, and other such matters. All these decisions must be considered when costs are being applied to the quantity surveys. In addition, work classifications used in quantity surveys must conform with the contractor's established cost accounting system.

It is interesting to note that in Great Britain, the quantity surveyor is an established part of the entire construction process. This party is hired by the owner at the inception of the project and makes cost feasibility studies, establishes a construction budget, makes cost checks at all stages of the design process, and prepares a final quantity takeoff. This takeoff is submitted to the contractors who will be bidding the project, and the contractors then use the quantity surveyor's information as the basis for their pricing of the work. Additionally, the quantity surveyor advises the owner on contractual arrangements and compiles certificates of interim and final payment to the contractor who is performing the work. In some ways, the duties of the British quantity surveyor and the American construction manager, especially when the construction manager is acting as an agent of the owner, are quite similar.

5.13.1.4 Materials Pricing

After determining the quantity and quality of materials the contractor will need to purchase for the project, the estimator will next determine prices for each of these materials. The estimator will contact materials suppliers, distributors, or manufacturers and will solicit price quotations for each of the materials to be purchased. The estimator will furnish information to the materials suppliers regarding the exact description of the material, the quality level in which the material is specified, and the quantity of each material to be purchased. Materials suppliers will provide price quotations in response to the estimator's request, and the estimator will tabulate the price quotations, and then will compare them and determine the price to be included in the estimate for each material.

The estimator will compile this information for each material, and will then determine the dollar amount that the company will expect to pay for the material when the project is performed. The estimator must include in the materials price determination, details such as applicable taxes, shipping fees, delivery fees, special handling requirements, and so forth, for the materials, all of which will add an increment of cost to the original quoted price.

In addition, suppliers will often include the designation FOB in their price quotations, which translates literally to “free on board” or “freight on board.” The FOB designation in a price quotation will be accompanied by a specific location or destination, as stipulated by the vendor (e.g., “FOB my loading dock, Kansas City, Missouri”). This location is the designated place where the supplier will have the material located for the contractor when the material is purchased. This location might be the supplier's or manufacturer's location, a warehouse, or a port facility. Or it could be the contractor's job site. This is also the location to which the supplier assumes responsibility and the point at which the contractor assumes responsibility for the material or product at the price that has been quoted. Additional information regarding the FOB designation is provided in subsequent sections of this book.

When all of the elements of the cost of each material have been finalized, all of the prices for all of the materials needed for the project are totaled by the estimator. This total becomes the materials cost subtotal in the estimate.

While this process may seem direct and straightforward, there is actually a considerable degree of uncertainty, and therefore risk, in this materials price determination. First, there is no relief for the contractor if the estimator's identification of the materials required or his determinations of the necessary quantities are inaccurate. The contractor is required to provide and install the materials necessary to fulfill the requirements of the contract documents without regard to whether this is the quantity determined by the estimator.

Additionally, some materials prices are stable, while others fluctuate. Time will elapse between the taking of the price quotation from the supplier, and the point in the future when the material is actually purchased for the project. Materials prices will often change during that time.

Sometimes materials suppliers will guarantee their materials price quotations for a specified period of time following their initial price quotation, but often not. Therefore, the price that the estimator includes in the estimate at the time of its preparation must reflect, as nearly as possible, the price for which he or she expects the company to buy the material on that date in the future when that material is actually purchased for the project.

While materials are frequently purchased from suppliers or distributors as previously described, there are times, especially on engineered projects, when the contractor produces its own materials, for example, when a contractor is producing its own aggregate as required for a highway project. In such an instance, the contractor would determine its own cost of production, per cubic yard or per ton, by determining the costs of drilling, blasting, crushing, screening, stockpiling, and delivering the required aggregate to the several portions of the project. Similarly, highway and heavy construction contractors frequently install their own batch plants on the site for the production of portland cement concrete and asphaltic concrete for the project.

5.13.1.5 Materials Price Summaries

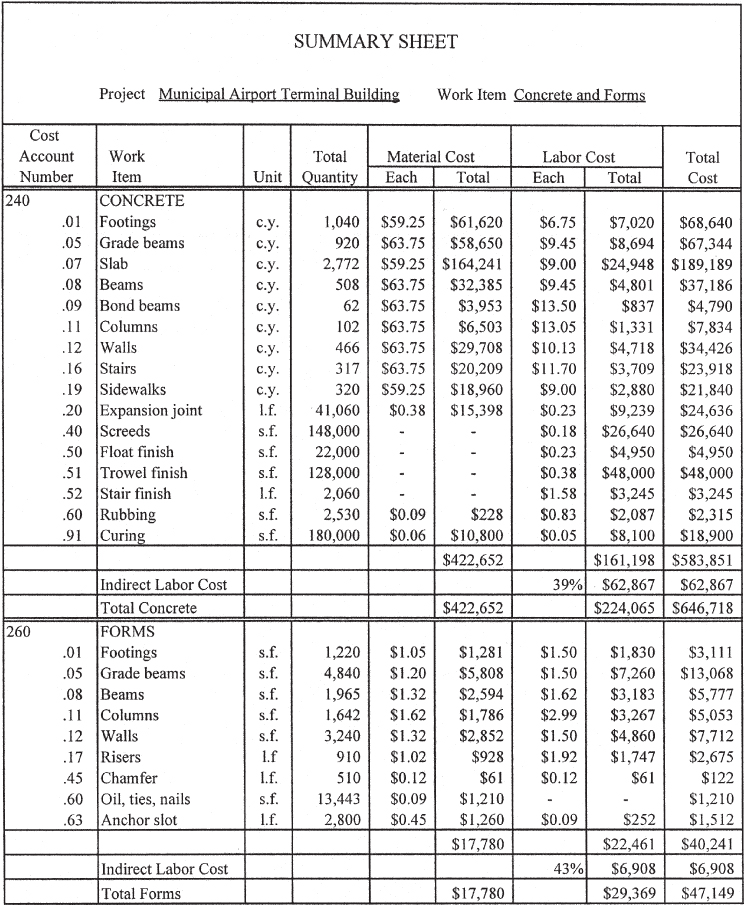

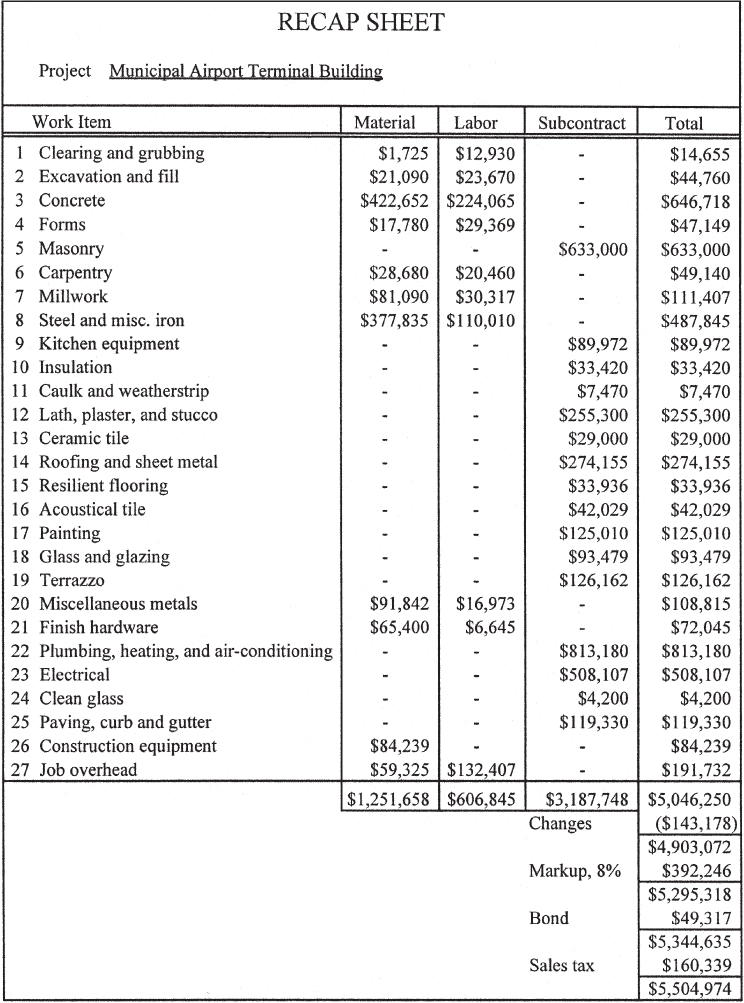

Upon completion of the quantity survey by the estimator, most contractors enter the materials prices onto some type of summary sheet or into their estimating spreadsheet or software. Usually, the total amount of each work classification is obtained and listed. Figure 5.4 presents a form of summary commonly used for a lump-sum project. For this type of contract, a similar summary is prepared for each major work classification. Figure 5.4 contains final quantities of concrete and formwork materials on the Municipal Airport Terminal Building, a hypothetical project that will be used in this text to illustrate selected procedures.

Figure 5.4 Summary Sheet Lump-Sum Bid

Similar summaries are prepared for all of the other principal work types. When the total quantities of work for each classification have been entered, the summary is then used for the pricing of materials.

Figure 5.5 shows an example of a materials summary for an engineered project where a unit-price contract is employed. For this type of bidding on an engineered project, a summary is prepared for each bid item. As illustrated in Figure 5.5, all work types associated with the accomplishment of that bid item are listed on the summary, which often includes several different work categories. With the work quantities obtained from the takeoff, the contractor uses the cost summary to obtain the total direct costs of that bid item. The summary sheets for unit-price projects customarily serve for the computation and recording of material, labor, equipment, and subcontract costs. Figure 5.5 illustrates this point as well.

Figure 5.5 Summary Sheet Unit-Price Bid

It should be noted that each work classification entered on a summary is typically identified by a cost account number. These numbers are the company's standard cost account numbers, which are basic components of its cost management system and historical information database system. Each estimate is broken down in accordance with the established cost accounts. Chapter 12 discusses the essentials of a contractor's project cost management system.

5.13.1.6 Alternate Materials

As discussed in Chapter 4, the material specifications on certain projects require that a specifically named product be furnished (closed specification), while sometimes providing the bidding contractor the right to propose a less costly substitute as an alternate in its proposal. When the contractor determines the amount of its bid, the cost of the specified product is used. However, the proposal also identities the substitute product proposed for use and the difference in price to the owner if the alternative product is approved.

5.13.1.7 Owner-Furnished Materials or Items

It is not unusual for the bidding documents to provide that certain materials will be supplied by the owner to the contractor at no charge. These materials are referred to as owner-furnished materials or owner-furnished items.

For these items or materials, no material costs per se need to be obtained by the contractor or be included in the project cost estimate. However, all other costs associated with such materials, such as job site storage and protection, and handling or lifting, as well as installation costs, must be included.

5.13.1.8 Allowances

On occasion, the architect-engineer or owner will designate in the bidding documents, a fixed sum of money that the contracting firm is directed to include in its estimate to cover the cost of some designated item of work. This is called an allowance and is often used with regard to materials such as finish hardware, face brick, or light fixtures. Such an allowance establishes an approximate material cost for bidding purposes in those instances in which the designer does not prepare a detailed material specification, or where a selection of the exact product to be used has not been made, in advance of bidding.

The contractor does not solicit material prices for these items, but rather simply includes the designated allowance amount in the bid. After the contract is awarded, at some point a final material selection is made by the owner or architect-engineer, and the contractor purchases and installs that which has been selected.

The inclusion of an allowance in the proposal does not necessarily mean the contractor is entitled to receive payment in the amount of the allowance. The contract documents typically provide that, after the completion of construction, an adjustment in the contract amount will be made for any difference between the designated allowance amount for an item and the final actual cost of that item.

5.14 Estimating Labor Cost

5.14.1 Direct Labor

As noted earlier, the estimator will ordinarily calculate labor costs for the craft labor that the contractor plans to self-perform, that is, to perform with craft workers on his payroll. Having decided what parts of the work will be self-performed and what parts of the work will be performed by subcontracting, the estimating staff will determine the labor cost of the contractor's craft labor forces that will perform work on the project.

While there are a number of different approaches to the process of labor estimation, many estimators believe that the best approach is for the estimator to “build the job in his mind” and to estimate labor in doing so. In building the project in his mind, the estimator will determine all of the activities that must be performed in order to complete the work. Activities are defined as elements of work that are identifiable and quantifiable and that consume resources.

Next, the estimator will envision the number and the classification—how many journeymen, apprentices, crew leaders, and so on—of craft workers necessary to perform each defined activity. This is referred to in estimating terminology as making the work breakdown structure (WBS).

The next crucial step is determining, literally estimating, the number of man-hours necessary for the crew and each of its craft workers to complete each activity that has been identified. This component of the labor estimate is both vital and, at the same time, filled with uncertainty.

This determination of craft labor hours is vitally important because this is where labor man-hours are quantified. Obviously, this determination will form the basis for the quantification of labor cost on the project. On building construction projects, labor cost is typically the largest single component of the total cost of a construction project.

At the same time that the quantification of labor craft hours, and therefore labor cost, forms the basis for the largest component of the cost of a project, this determination is also the most uncertain and therefore the most risky component of the estimate. This is true because estimating labor man-hours is literally based on estimating the productivity of the craft labor on the project. It is one of the ironies, and also one of the elements of difficulty associated with cost estimating, that labor is both the largest component of cost within an estimate and at the same time the most difficult and therefore the most risky-to-estimate component of construction cost.

There are many factors that influence what the labor productivity will be on a construction project, and many of these factors are difficult to predict in advance. Additionally, their impact on labor productivity is difficult to quantify. A few examples will illustrate this point.

Weather has a profound influence on labor productivity. Hot and cold weather, high humidity, wind, and precipitation all have an influence on the rate at which craft labor can perform the work. While general weather trends can usually be predicted, the daily weather and its variability, as well as sudden and unforeseen weather events such as storms or precipitation, certainly affect productivity but cannot be predicted with accuracy.

Additionally, factors such as geographic location of the project, the composition of the construction team—owner, architect, general contractor personnel, subcontractors, building officials, and so on—all have a bearing on the craft labor productivity on a project. Likewise, the composition and management abilities of the contractor's team—supervisor, superintendent, project manager, and office staff—also have an influence. All of these various factors exert an influence on how craft labor does its work and how productive the craft workers will be.

While other factors could be listed that may impact labor productivity, it should now be clear that the estimator faces a daunting task in his endeavor to quantify and to determine the cost of craft labor and its performance of the construction work on a project. Nonetheless, the estimator must make the best prediction possible of the cost of labor to perform the project, given the time and other resources available.

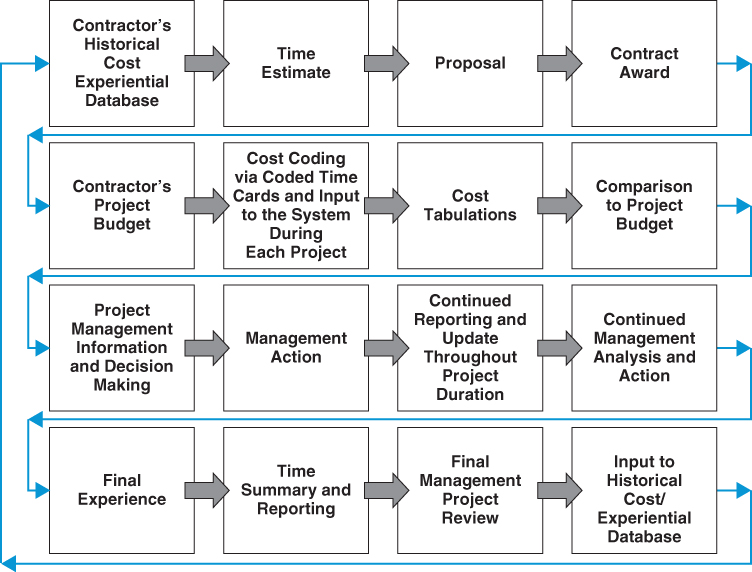

To accomplish this task, there are several different methodologies that may be employed. Both of the methods described here make extensive use of the historical cost information that the contractor's cost estimating, cost accounting, and cost control system has developed. This is, in fact, the very reason for the contractor's compiling and maintaining this file of information. While the system or cycle of cost accounting and management will be further discussed in another chapter, the relationship of this cycle and its historical cost information database to the process of estimating labor is shown in Figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6 Cycle of Cost Accounting, Cost Reporting, and Cost Control, and Historical Information Database

The historical cost data is a tabulation of the contractor's costs of performing work, by project and by activity, on past projects. This information is generated as each project is performed, and is stored in a systematic manner in the historical cost database. This database is one of the contractor's most important and most closely guarded assets.

By one estimating philosophy and methodology, the estimator “builds the job in his mind” and estimates construction costs as though this database of information did not exist. He proceeds with estimating labor as we have described, envisioning activities to be performed, determining the WBS, and estimating craft labor man-hours for the performance of the work. Periodically during the development of the estimate, or sometimes when the labor estimate is complete, the estimator will then check the values he has derived in his estimate, against labor man-hours for the same activities on similar or comparable projects that have been completed on the past, as stored in the historical cost information. This comparative analysis allows the estimator to determine his comfort level with the values he has derived in this estimate, as a function of how these values compare to the contractor's experience on similar activities and projects that the contractor constructed in the past.

A second method for estimating labor is the converse of the first. By this approach, estimators consult the historical information first, and based on the activities to be performed on the project currently being estimated, they then extract from the historical information the number of man-hours in the performance of these activities on past projects. The estimate being prepared presently is then structured accordingly. Finally, the estimators adjust the man-hours or production rates in the current estimate in such a way as to reflect their best determination of what the man-hours or production rates will be on the project currently being estimated, in order to reflect current conditions or influences on this project.

Certainly, individual estimators, as well as different construction company owners, have their opinions regarding which method of estimating labor yields the best results. In the final analysis, however, the conclusion is the same: the estimator must utilize his skill and judgment, and the best tools and resources available, to include the historical information database, to estimate with the greatest degree of certainty attainable, the cost of the craft labor in performing the construction work on the project.

Following the determination of all the activities to be performed in completing the work on the project and the estimation of the number of man-hours of craft work necessary to complete each activity, the estimator will develop totals for labor man-hours by craft and by skill level. The total number of master carpenter hours, journeyman carpenter hours, carpenter apprentice hours, ironworker hours, cement finisher hours, and the like will be determined.

The labor cost to be included in the estimate will then be calculated by multiplying the craft man-hours estimated for each craft, by the rate (dollars per hour) at which that craft and skill classification will be paid on the project. The total dollars determined by this process is referred to as the direct labor dollars.

In a variation of the process described above, estimators may also use historical cost information from past projects to produce production rates for different activities. Labor production rates, in turn, can be expressed in a variety of ways. One of these methods is to determine the man-hours or crew-hours required to accomplish a unit or prescribed number of units of a given work type. As an example, six hours of carpenter time and six hours of carpenter-helper time may be required to assemble, erect, plumb, brace, strip, and clean 100 square feet of rectangular concrete column forms.

To obtain the estimated labor cost for a given quantity of such work, the labor hours required per unit of work are multiplied by the appropriate wage scales per hour for the craft, and then are again multiplied by the total number of units of work of this category as obtained from the quantity survey.

A different way to express this type of labor production rate is the number of units of work accomplished per working day by a worker or by a crew in a certain craft. Another version of labor production rates is total man-hours or total crew-hours to complete a given job of work.

When estimating the costs of construction labor, a cost per unit of work, or a unit price, can be useful and convenient. For example, if carpenters earn $28.35 per hour, and a carpenter-helper's wage scale is $21.50 per hour, the rectangular column forms cited previously will have a labor unit cost of $2.99 per square foot [($28.35 + $21.50) × 6 ÷ 100]. These “labor unit costs” are quick and easy to apply, as illustrated by Figure 5.4. However, the estimator must ensure that his labor unit costs are kept up-to-date and that they reflect the probable levels of work production and the applicable wage rates.

Certainly, the most reliable labor productivity information is that which the contractor obtains from its own completed projects, stored in his historical cost database. Information on labor productivity and costs is also available from a wide variety of commercial sources. However, while information of this type can be very useful at times, it must be emphasized that labor productivity varies greatly from one geographic location to another and is further modified by seasonal influences and many other factors.

Estimators must be very circumspect when using labor unit costs that they have not developed themselves. For the same work items, different estimators will include different expense items in their labor unit costs. It is never advisable to use a labor unit cost derived from another source, without knowing exactly what it does and does not include.

5.14.2 Indirect Labor

The total labor dollars on the project will include the determination of both direct labor and indirect labor dollars, as illustrated in Figure 5.7. Indirect labor is also frequently referred to as labor burden.

Figure 5.7 Total Labor Dollars Determination for the Estimate

Indirect labor dollars are defined as dollars that the contractor must pay, expressed as a fraction or percentage in several different categories, for each direct labor dollar of labor cost. Examples include federal withholding taxes, Social Security taxes, workers' compensation insurance premiums, unemployment insurance premiums, union fringe benefits, employee medical care, and employer-furnished fringe benefits such as paid vacation time, pension plans, health and welfare funds, and so on.

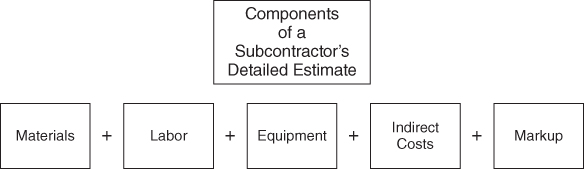

Each of these elements of indirect labor cost is typically defined as a percentage of direct labor dollars. Most contractors will tabulate the total of all of the indirect labor components to be included for each craft and skill level and will then apply that percentage as a multiplier to the direct labor for that craft and skill level. While the amount will vary by location and by contractor, the indirect labor is frequently in the range of 40 to 50 percent of the direct labor amount.