Chapter 6

Construction Contract Provisions

6.1 Introduction—Construction Contracts

Construction contracts exist in a number of variations, and contain numerous different provisions. Chapter 1 of this book provides an overview of the basic taxonomy for discussing and understanding the variations in forms of construction contracts: the single and separate contracts systems; competitive bid, negotiated, and competitive sealed proposals methods of forming contracts; and lump-sum, unit-price, and cost-plus forms of contract.

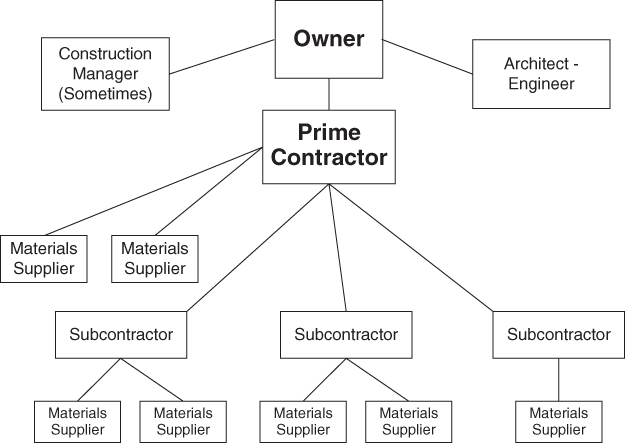

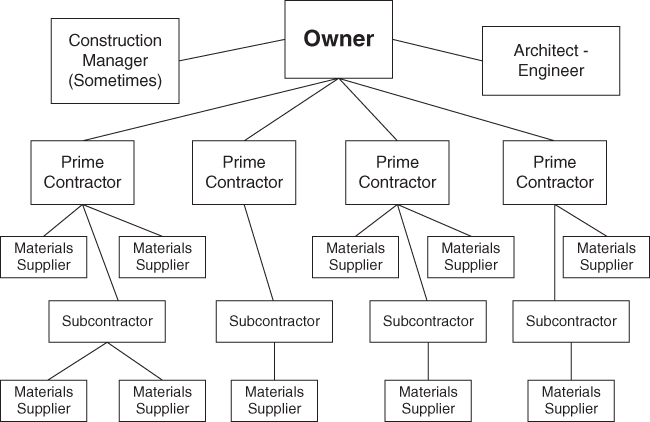

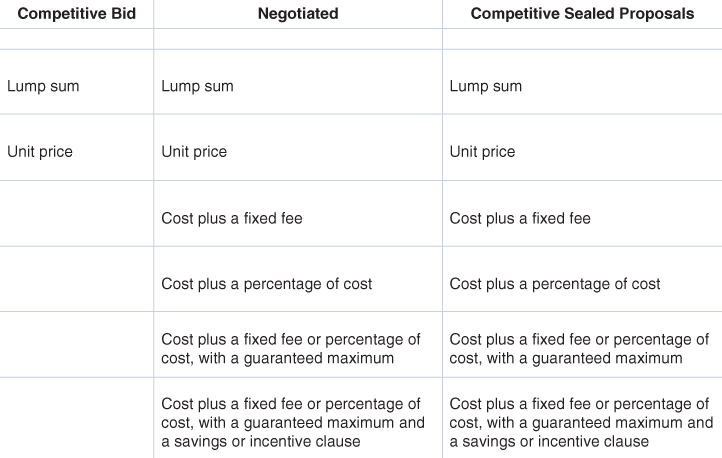

Figures 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3 provide a graphic overview of these classifications.

Figure 6.1 Single-Contract System

Figure 6.2 Separate-Contracts System

Figure 6.3 Project Delivery Methods and Forms of Contract

It is not the intent of this chapter to review the elements of all of these forms of contract; Chapter 1 defined and discussed each of them. Rather, it is the purpose of this chapter to discuss some of the workings of, and some of the common terminology and contract provisions contained in, these various forms of contracts. While certainly not every significant clause of every contract variation can be discussed, some of the more commonplace and typical contract provisions that are encountered and commonly utilized in the practice of construction contracting will be presented.

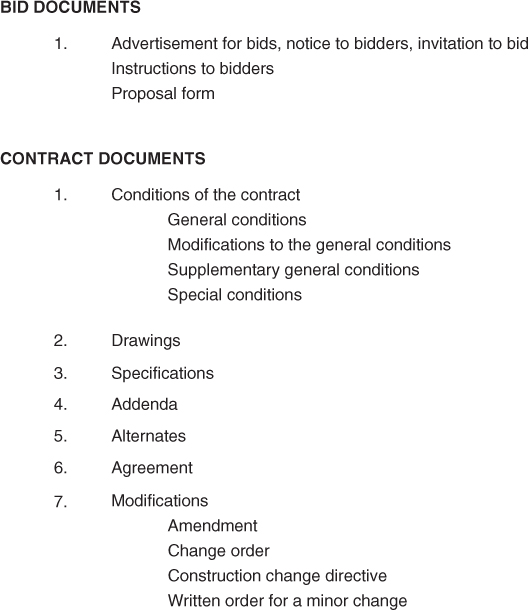

Most of the elements to be discussed are written into the bid documents and/or into the contract documents prepared by the architect-engineer in accordance with the terms of his contract for professional services with the owner. For reference, the typical set of contract documents produced by the architect-engineer for a project are listed in Figure 6.4. Each of these documents is defined and is more fully discussed in Chapter 4.

Figure 6.4 Bid Documents and Contract Documents for a Construction Project

6.2 Contract Clauses

As noted earlier, it is beyond the scope of this book to attempt a complete discussion of the meanings, significance, and legal implications of all contract clauses. However, the most important aspects of some of the principal contract provisions encountered in the practice of construction contracting are discussed under topical headings in this chapter. The following sections consider contract clauses of special significance that are not treated elsewhere in this book.

Construction contracts can and frequently do include provisions pertaining to specified liabilities, waivers, damages, responsibilities, requirements, and other disclaimers that are designed to protect the owner and/or the architect-engineer by transferring risk and uncertainty to the contractor. While it is true that there are limits to the enforcement of some of these types of contract provisions by the courts, the contractor cannot assume that such contract language will be unenforceable. Such exculpatory language has at times been invalidated by the courts where there was interference by the owner with the contractor's work or a failure on the part of the owner to act in some essential manner. However, the contractor cannot assume that such severe and seemingly unfair contract language will be unenforceable. Obviously, the time for a thorough study and evaluation of all contract documents and provisions is while the project is being considered, not after the contract is signed. After he has executed the contract, the contractor is bound by all of its provisions.

Contractors must recognize that they are not attorneys and therefore are not competent to appraise the legal implications inherent in certain contract clauses. Should the contractor not understand any clause or provision of any part of the contract documents, or should he have any uncertainty with regard to whether or not he fully understands the language and its implications, the contractor should immediately seek the assistance of his attorney. This should be accomplished before the contractor makes any binding commitments having to do with the bid documents or contract documents. The contractor's failure to do so can result in serious complications that often could have been avoided had legal advice been obtained.

During the time described in Chapter 4 as “making the decision to bid,” and during the bidding period, the contractor must carefully analyze all of the language of all of the contract documents, in order to make the decision with regard to whether he is interested in entering a contract which contains these provisions. If the contractor perceives a level of risk or uncertainty he is uncomfortable with, he will typically make the decision not to invest in the time, energy, and dollars necessary for preparing a proposal for submittal. If he has made a decision to submit a proposal, during the bidding period, he will evaluate each clause with regard to its possible or probable contribution to the cost of construction. Upon becoming the successful bidder and expecting to be the contract recipient, the contractor must again examine the contract documents but with a different purpose in mind. Many provisions of the contract require specific actions, often at certain times or within specified time limits, on the part of the contractor during the life of the contract.

These clauses must be carefully examined and studied by the contractor so that the obligations to be assumed, along with their timelines, are thoroughly understood. When standard document forms are involved, such as those of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), the federal government, the Associated General Contractors of America, or the Engineers Joint Document Committee of the American Society of Civil Engineers, there is seldom a need for the contractor to concern itself unduly with ferreting out untenable provisions. These standard contract documents have well-established records of service and have become familiar to many practitioners in construction contracting. Many of them have received legal interpretation by the courts. However, the modifications to the conditions of contract, the special conditions, or the supplementary conditions, inasmuch as they are typically written by the architect-engineer specifically for a project, certainly bear special scrutiny.

6.3 Rights and Responsibilities of the Owner

Construction contracts typically reserve a number of rights to the owner of the project. These rights will almost always be clearly set forth in the contract documents, usually in a special section of the general conditions titled “Rights and Responsibilities of the Owner.” The AIA General Conditions of the Contract for Construction, included as Appendix D, contains such a section.

Depending on the type of contract and its specific wording, the owner may be authorized to award other contracts in connection with the work, to require contract bonds from the contractor, to approve the surety proposed by the contractor, to retain a specified portion of the contractor's periodic payments, to make changes in the work, to carry out portions of the work in case of contractor default or neglect, to withhold payments from the contractor for adequate reason, and to terminate the contract for cause. The right of the owner to inspect the work as it proceeds, to direct the contractor to expedite the work, to use completed portions of the project before project completion and contract termination, and to make payment deductions for uncompleted or faulty work are common construction contract provisions. The owner is normally free to perform construction or operations at the site with its own forces or with separate contractors, as well.

At the same time, the contract between the owner and the contractor imposes certain responsibilities on the owner, which are also clearly called out in the general conditions. For example, construction contracts make the owner responsible for furnishing property surveys that describe and locate the project, granting the contractor timely access to the work site, securing and paying for necessary easements, providing certain insurance, and making periodic payments to the contractor. The owner is required to make extra payments and grant extensions of time in the event of certain eventualities as provided for in the contract. When there are two or more prime contractors on a project, the owner may have a duty to coordinate these separate contractors and their field operations.

It is important to note that the owner cannot intrude on the direction and control of the contractor's operations. By the terms of the usual construction contract, the contractor is known in the law as an independent contractor. Even though the owner enjoys certain rights with respect to the conduct of the work, he cannot issue direct instructions with regard to methods or procedures, nor unreasonably interfere with construction operations, nor otherwise unduly assume the functions of directing and controlling the work. If he were to do so, the owner could thereby relieve the contractor from many of the contractor's legal and contractual responsibilities. If the owner oversteps his rights, he may not only assume responsibility for the accomplished work but may also become liable for negligent acts committed by the contractor in the course of construction operations.

Under the laws of most states, the owner is responsible to the contractor for the adequacy of the design. If the drawings and specifications are defective or insufficient, the contractor can usually recover the resulting costs and extensions of time from the owner. Because the contractor must perform the construction in accordance with the contract documents, the owner implicitly warrants their accuracy and sufficiency for the intended purpose. The contractor is not responsible for the end results and is not liable for the consequences of design defects. In this regard, it should be noted that the contractor does typically have a duty to inform the owner and the architect-engineer if he knows or could reasonably have been expected to know of serious errors or insufficiencies in the design.

The responsibility of the owner for the design is not overcome by the usual bidding clauses requiring bidders to visit the site, to check the drawings and specifications, and to inform themselves concerning the requirements of the work. It must be noted, however, that the owner's responsibility for the design does not protect the contractor who does not fully comply with the contract. The implied warranty that the contract drawings are adequate for the purpose intended is limited to those cases where the contractor has followed and has complied with the drawings and specifications.

6.4 Duties and Authorities of the Architect-Engineer

Other than cases in which both design and construction are performed by the same contracting party or in which the owner has an in-house design capability, the architect-engineer firm that has a contract with the owner is not a party to the construction contract and has no contractual relationship between itself and the contractor. The architect-engineer is a third party to the construction contract that derives its rights and authorities over the construction process from the general contract between the owner and the prime contractor. When private design professionals are utilized by the owner, the effect on the construction contract is to substitute the architect-engineer for the owner in many important respects. However, the jurisdiction of the architect-engineer to make determinations and to render decisions is limited to and circumscribed by the terms of the construction contract.

The architect-engineer typically represents the owner in the administration of the contract and acts for the owner during the day-to-day construction operations. The architect-engineer advises and consults with the owner, and communications between owner and the contractor are made through the architect-engineer. Appendix D, “AIA Document A201–2007, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction” contains typical provisions regarding the architect-engineer's role in contract administration.

Construction contracts often impose many duties and bestow considerable authority on the design firm. All construction operations are conducted under its attentive observation, and it generally oversees the progress of the work. It has a direct responsibility to the owner to see that the workmanship and materials fulfill the requirements of the drawings and specifications. To ensure this fulfillment, the architect-engineer can exercise the right of observation of the work and approval of materials to be included in the work. The contractor is required to allow access by the architect-engineer to the project during the course of the work for this purpose. Also included may be the right of approval of the contractor's general program of field procedures and even the construction equipment the contractor proposes to use. Should the work be lagging behind schedule, the architect-engineer may reasonably instruct the contractor to speed up its activities. Many contracts bestow upon the architect-engineer the right to stop the project or any part thereof to correct unsatisfactory work or conditions. The specific language in this regard is widely variable, ranging from a very broad right to a more limited right.

The foregoing paragraph does not mean that the architect-engineer assumes responsibility for the contractor's methods, merely because he retains the right of approval. The rights of the architect-engineer are essentially concerned with verifying that the contractor is proceeding in accordance with compliance with the contract documents. It should be pointed out, however, that the architect-engineer cannot unreasonably interfere with the conduct of the work or dictate the contractor's procedures or work methods. Again, if the direction and control of the construction are taken out of the hands of the contractor and are assumed by the architect-engineer, the construction firm may be effectively relieved of many of its legal and contractual obligations.

The contract documents often authorize the architect-engineer to be the interpreter of the provisions and requirements of the contract and to be the judge with regard to acceptability of the work performed by the contractor. The architect-engineer occupies a position of trust and confidence in this regard and must act in good faith throughout the construction process. When this party provides for itself the right of acting as the official interpreter of contract conditions and as a judge of the contractor's performance, it must exercise impartial judgment and cannot favor either the owner or the contractor. Sometimes the courts have held that if the contractor made an interpretation of the language of the contract documents that is deemed to be reasonable, then the interpretation made by the contractor will prevail.

Some contracts provide that the architect-engineer's decisions are not final and that the owner and contractor can exercise their rights to arbitration or to the courts, providing the architect-engineer has rendered a first-level decision. Other contracts state that the architect-engineer's decisions are final and binding on both parties with regard to artistic effect only. Still other contracts give the architect-engineer broad authority to make final decisions concerning the quality and fitness of the work and to interpret the contract documents.

In matters where the architect-engineer is given final and binding authority, this is necessarily restricted to questions of fact. In the absence of fraud, bad faith, and gross mistake, the decision of the architect-engineer can be considered as final, provided the subject matter falls within the proper scope of authority given to the design firm by the construction contract. With respect to disputed questions of law however, the architect-engineer has no jurisdiction. It cannot deny the right of a contractor to due process of law, and the contractor has the right to submit a dispute concerning a legal aspect of the contract to arbitration or to the courts, as may be provided by the contract. Matters pertaining to time of completion, extensions of time, liquidated damages, and claims for extra payment usually involve points of law.

Architect-engineers can be liable to the owner and third parties for damages resulting from their negligence or lack of care. Where the contractor has complied with the provisions of the drawings and specifications prepared by the architect-engineer, and these documents prove to be defective or insufficient, the architect-engineer will be responsible for any loss or damage resulting from the design defect. This rule is subject to the absence of any negligence on the part of the contractor, or any express warranty by the contractor that the drawings and specifications were sufficient or free from defects.

6.5 Indemnification

The vulnerability of architect-engineers to third-party suits is discussed in other chapters of this book. Owners and architect-engineers endeavoring to protect themselves by use of indemnification clauses in the contract is included here because of its obvious significance as an important element of the contract for construction, In like manner, owners are subject to claims by third parties to the construction contract for damages arising out of construction operations.

The rule that one who employs an independent contractor is not liable for the negligence or misconduct of the contractor or its employees is subject to many exceptions. To protect the owner and architect-engineer from third-person liability, many construction contracts include indemnification or “hold-harmless” clauses. Indemnification means that one party compensates a second party for a loss that the second party would otherwise bear.

Hold-harmless clauses typically require that the contractor indemnify and hold harmless the owner and the architect-engineer, and their agents and employees, from all loss or expense occurring by reason of liability imposed by law on them for damages because of bodily injury or damage to property arising out of, or as a consequence of, the work. The present tendency is for parties who may have been injured by construction operations to bring suit against practically everyone associated with the construction. Additionally, the courts have shown a growing inclination to ascribe liability, in whole or in part, for such damages to the owner or architect-engineer. For example, owners and architect-engineers have been made responsible for damages caused by construction accidents where adequate safety measures were not taken on the project.

Hold-harmless clauses are by no means uniform in their wording. However, these clauses can be grouped into three main categories:

- Limited-form indemnification. The limited form holds the owner and architect-engineer harmless against claims caused solely by the negligence of the prime contractor or a subcontractor.

- Intermediate-form indemnification. The intermediate form includes not only claims caused by the contractor or its subcontractors but also those in which the owner and/or architect-engineer may be jointly responsible, regardless of degree of fault. This is the most prevalent type of indemnification clause, and is the type contained in the AIA Document A201–2007, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction, in Appendix D.

It is to be noted in Appendix D that the obligation assumed by the contractor does not extend to liability arising out of certain acts of the architect-engineer.

- Broad-form indemnification. The broad form indemnifies the owner and/or architect-engineer against all losses, even when the party indemnified is solely responsible for the loss.

When broad-form hold-harmless clauses are used, contractual liability coverage is expensive and some provisions may not be insurable. The effect is compounded when the general contractor logically requires the same indemnification from its subcontractors. Some courts frown upon the use of broad-form indemnification, but such clauses have frequently been upheld by the courts. Most states have enacted laws that make it impossible for a contractor to indemnify an architect-engineer from liability arising out of defects in plans and specifications, and many states have passed laws that make void and unenforceable, certain forms of indemnification clauses in construction contracts.

Indemnification clauses are also routinely included in subcontracts. By the terms of these provisions, the subcontractor agrees to hold harmless the general contractor, the owner, and perhaps the architect-engineer. In the presence of such language these indemnified parties are protected against liability that may devolve to them out of or as a consequence of the performance of the subcontract. Just as the general contract can relieve the owner and/or architect-engineer from liability even when they are at fault, a subcontract indemnity clause can be worded so that it acts to relieve the general contractor, owner, and architect-engineer from liability even when they may be at fault.

It is a principle of long standing that a party may protect itself from losses resulting from liability for negligence by means of an agreement to indemnify. However, the rule is restricted to the extent that contractual indemnity provisions will not be construed to indemnify a party against its own negligence unless such intention is expressed in unequivocal terms. When such a clause is to be included in subcontracts, it must explicitly provide that the subcontractor indemnifies the designated parties whether or not the liability may be caused solely by them.

6.6 Rights and Responsibilities of the Contractor

The architect-engineer, who has privity of contract with the owner, typically writes the construction contract that the owner and contractor will sign, as part of his duties in fulfilling his contract with the owner. The contractor has some rights and many obligations under the typical contract. The primary responsibility of the contractor is, of course, to construct the project in conformance with the requirements of the contract documents.

Despite almost any events that may occur, the fundamental expectation of the contractor is that he will complete the work on the project on time and in the prescribed manner. Although some situations may justify allowing more construction time to complete, only severe contingencies, such as impossibility of performance, can serve to relieve the contractor from its obligations under the contract.

The contractor is expected to give his personal attention to the conduct of the work on the project, and the contract typically requires that a responsible company representative must be on the job site at all times during working hours. The contractor is required to conform to all laws and ordinances concerning job safety, licensing, employment of labor, sanitation, insurance, traffic and pedestrian control, explosives, and all other aspects of the work. Many contracts now include rules that are designed to decrease air and noise pollution on construction projects, imposing regulations and restrictions concerning such operations as demolition, trash disposal, pile driving, riveting, fences, lighting, dust, noise, and housekeeping.

The contractor is required to follow the drawings and specifications and cannot be held to a guarantee that the completed project will be free of defects or that the completed work will accomplish the purpose intended. However, if the contractor deviates from the design documents without consent of the owner, the contractor does so at its own peril and assumes the risk of the variation. The contractor has the right to rely on the accuracy and adequacy of the contract documents. Unless the contract expressly requires such action, the contractor has no duty to review or verify the design. The contractor is responsible for and warrants all materials and workmanship, whether put into place by its own forces or those of its subcontractors, to be in accord with contract provisions. Contracts typically provide that the contractor shall be responsible for the preservation of the work until its final acceptance. Even though the contractor has no direct responsibility for the adequacy of the drawings and specifications, it can incur a contingent liability for proceeding with faulty work whose defects are apparent.

The contractor must call all obvious design errors and discrepancies to the attention of the owner and architect-engineer. Otherwise, the contractor proceeds at his own risk because a party who builds according to patently defective drawings and specifications can be held responsible for any resulting liability. Should an instance occur in which the contractor is directed to do something he believes is not proper and not in accordance with good construction practice, he should protect himself by writing a letter of protest to the owner and the architect-engineer, clearly stating his position before proceeding with the matter in dispute.

Insurance coverage is an important contractual responsibility of the contractor, both as to the type of insurance and the policy limits. The contractor is required to provide insurance not only for its own direct and contingent liability but frequently also for the owner's protection as well. Chapter 8 discusses insurance provisions in greater detail.

The contractor is expected to exercise every reasonable safeguard for the protection of persons and property in, on, and adjacent to the construction site. Where contract surety bonds are required by the owner, the contractor is responsible for furnishing them in the proper amounts before field operations commence. Sureties and surety bonds are further discussed in Chapter 7.

Additional important contractor rights set forth in the contract documents concern progress payments, recourse should the owner fail to make payments timely, termination of the contract for sufficient cause, right to extra payment and extensions of time, and appeals from decisions of the owner or architect-engineer. Subject to contractual requirements and limitations that may be set forth in the contract documents, the contractor is free to subcontract portions of the contract, and to purchase materials where it chooses, and to proceed with the work in any manner and in any sequence that it chooses.

6.7 Subcontracts

A subcontract is an agreement between a prime contractor and a subcontractor by which the subcontractor agrees to perform a certain specialized and defined portion of the work. As has been noted previously, a subcontract does not establish any contractual relationship between the subcontractor and the owner, nor between the subcontractor and the architect-engineer. A subcontract binds only the parties to the agreement, the prime contractor and the subcontractor.

Nevertheless, construction contracts frequently stipulate that all subcontractors shall be approved by the owner or architect-engineer. The bidding documents may require that a list of subcontractors be submitted with a proposal submitted by a prime contractor, or that a similar list be submitted by the low-bidding prime contractor for approval by the owner after the proposal has been accepted. When the owner is provided the right of approval, the general contractor is not relieved of any of its responsibilities by the owner's exercise of its prerogative.

If approval of subcontractors is required, such approval must be obtained before the general contractor enters into agreements with its subcontractors. This frequently presents a very awkward situation, for both the prime contractor and the subcontractors. As discussed in other sections of this book, the relationship between prime contractors and certain of their subcontractors is often a special business relationship, frequently cultivated over a period of time. If one or more of the prime contractor's subcontractors of choice is not approved by the owner and architect-engineer, then, by definition, the prime contractor will be entering subcontract agreements with subcontractor specialists who were not their first choice. Additionally, if the second subcontractor submitted a price for its work that was higher than that of the first subcontractor who was disapproved, the matter of who is responsible for payment of the higher amount has sometime become a contentious issue.

In actuality, the disapproval of a subcontractor by the architect-engineer and owner is not a common occurrence. This is particularly true on public projects, where disapproval of a subcontractor may result in litigation and can be difficult to sustain by the public owner.

The prime contractor typically formalizes all of the elements of its contract with the subcontractors by use of a written document called the subcontract agreement. This document sets forth in detail the rights and responsibilities of each party to the contract. A well-prepared subcontract agreement can eliminate many potential disputes concerning the conduct of subcontracted work. The prime contractor may use a standard subcontract form, or it typically may develop its own special form to suit its particular requirements. Subcontract forms should be prepared with the exercise of extreme care and with the assistance of an experienced attorney. The Associated General Contractors of America has prepared a form of subcontract agreement for use on building construction projects that is presented in Appendix L.

A frequent area of disagreement between the general contractor and a subcontractor is the form and language of the subcontract agreement that is used for a project, and the terms and conditions that the form includes. Sometimes, when a subcontractor has previously done work for a general contractor, the subcontractor tacitly assumes that the same subcontract form that the general contractor previously used will again be employed. Consequently, the subcontractor's bid often includes, without specific reference, the standard contract terms and conditions previously used by that general contractor. Problems arise when the subcontractor submits a bid to a general contractor for the first time or when the general contractor makes some major revisions to its company subcontract form. Here, the contract terms contemplated by the two parties can be quite different.

A possible complication here is that if the general contractor presents a subcontract agreement for the subcontractor to sign that contains significant conditions not set forth in the bidding documents or contract documents, it can be considered as a counteroffer by the general contractor, and the bid of the subcontractor may not be binding. To avoid such difficulties, many general contractors require that subcontract bids be submitted on a standard bid quotation form that binds the parties to the use of a particular subcontract. Typically, this form will indicate that the subcontract agreement form to be used is available for examination by the subcontractor before their subcontract proposal is submitted.

After the subcontract agreement is signed and the work is under way, change orders to construction contracts often are issued and agreed to between the contractor and the owner. Frequently, these change orders involve modifications to subcontracted work. When this is the case, the general contractor and the subcontractor must execute a suitable change order to the subcontract agreement affected.

6.8 Subcontract Provisions

Subcontract agreements are, in many respects, similar in both form and content to the prime construction contract between the general contractor and the owner. Two parties contract for a specific well-defined body of work that is to be performed in accordance with a prescribed set of contract documents. Normally, the general contractor will include in its subcontract agreements express provisions that the subcontractor is bound to the prime contractor to the same extent that the prime contractor is bound to the owner by the terms of the prime contract. Provisions of this kind are commonly referred to as “pass-through clauses” or as “pass-through provisions.”

Additionally, the subcontract must provide that the subcontractor assume all obligations to the prime contractor that the prime contractor assumes to the owner. This concept is illustrated in Appendix D. With such wording, provisions of the general contract such as changes, changed conditions, prevailing wages, warranty period, compliance with applicable laws, and approval of shop drawings that pertain to the prime contractor also extend to the subcontractors. Other owners require the general contractor to include in its subcontracts certain provisions or designated clauses that appear in the general construction contract.

Project specifications normally include a description of those work items for which warranties and guarantees are required. A common area of dispute between the general contractor and its subcontractors is whether these warranty and guarantee periods begin when the specific work is completed, or when the entire project is finalized. A common procedure in this regard is for all subcontract agreements to clearly state that the effective beginning dates of warranty and guarantee periods shall coincide with the completion of the total project and final acceptance by the owner.

In addition to the provisions of the general construction contract, there are many relationships that pertain to the conduct of the subcontracted work itself for which provision must be made. Many of these are in the nature of general conditions to the subcontract, which are made an integral part of the printed subcontract agreement form. Clauses pertaining to temporary site facilities to be furnished, insurance and surety bonds to be provided by the subcontractor, arbitration of disputes, extensions of time, and indemnification of the general contractor by the subcontractor, are typical illustrations.

A detailed description of the work to be accomplished by the subcontractor, referred to as a scope statement, must be included in the subcontract agreement. A statement concerning the starting time, and the schedule of the subcontracted work, as well as provisions relating to the contractor's overall scheduling of the work on the project, and inclusion of liquidated damages statements, are important. Subcontracts often contain a “no damage for delay” clause. This clause provides that, in the ease of delay caused by the general contractor, the subcontractor's sole remedy will be an extension of time to complete its work. Special conditions must often be included such as security clearances for workers, job site storage, laydown areas, work to be accomplished after hours, and other requirements that arise from the peculiarities of a given project. Some subcontracts provide that the subcontractor must waive its right to file a mechanic's lien against the project property site. However, some states have enacted statutes making such waivers void as against public policy. Liens are more fully discussed in Chapter 9.

Because the subcontractor has no contract with the owner, the subcontractor normally cannot sue the owner directly as a means of settling disputes or claims. Rather, the subcontractor must either initiate a claim in the name of the prime contractor or have the prime contractor prosecute the claim for the subcontractor. In addition, the subcontractor cannot submit a claim against the owner after the general contractor has finalized the project and released the owner by acceptance of final payment. Consequently, subcontracts sometimes include a clause obligating the prime contractor to pursue any subcontractor claims against the owner or allowing the subcontractor to pursue them in the name of the prime contractor. It is to be noted that owners are generally precluded from suing a subcontractor for a breach of the subcontract, not only because these two parties are not in contract but also because the law generally regards the owner as an incidental beneficiary to the subcontract and not as a third-party beneficiary.

Terms of payment to the subcontractor and retainage to be withheld by the general contractor are, of course, especially significant. Payment to the subcontractor can be established as a lump-sum, unit-price, or cost-plus basis. Most subcontract agreements contain provisions to the effect that the subcontractor will be paid at 30-day intervals on an earned-value basis, in accord with the manner in which the prime contractor is paid by the owner.

A matter of continuing concern to all parties is payment to the subcontractor by the general contractor when, for some reason, the general contractor has not been paid by the owner. Different subcontract agreements contain significantly different provisions in this regard. All subcontracts stipulate that the general contractor shall pay its subcontractors promptly after payment is made by the owner to the prime contractor, although some obligate the contractor to pay the subcontractors only after owner payment. The subcontract agreement form in Appendix L provides that payment to the subcontractor is conditioned on receipt by the prime contractor of its payment from the owner.

Such contract provisions have raised many questions concerning the responsibility of the prime contractor to pay the subcontractor and have resulted in a great deal of litigation. Most courts now hold that the subcontract must be explicit with regard to the assumption of risk by the subcontractor concerning delay of payment by the owner, if the contractor is to be authorized to withhold payment from the subcontractor. If such contractual wording is not present, the subcontractor must normally be paid within a “reasonable time” for completed and acceptable work.

In addition, the courts note that delay in payment by the owner generally involves a dispute between the owner and the general contractor. If this dispute does not involve a particular subcontractor, the courts have ruled that the uninvolved subcontractor is entitled to payment within a reasonable time, even if the prime contractor has not been paid. It is to be noted that some subcontract forms do not contain a contingent payment provision but do provide that subcontractor payments are contingent on payment certificates being issued by the architect-engineer.

It is also to be noted that some general contractors operate by a management philosophy that holds that their subcontractors are to be paid for work they have properly installed and completed, without regard to whether the general contractor has been paid by the owner. This philosophy is translated into appropriate language to that effect in the subcontract agreements utilized by these general contractors.

Progress payments to subcontractors by the prime contractor are normally subject to the same retainage provisions as apply to payments made by the owner to the prime contractor. Such retainage is provided for by the subcontract instrument.

A matter that requires close attention by the general contractor is the possible lack of coordination between provisions of the prime contract and of the subcontract form used on a given project. Uncoordinated contract terms can lead to serious legal difficulties for the prime contractor. Again the point is to be emphasized that the wording and the formation of subcontract agreements for construction projects should command the complete attention of the general contractor, with the assistance of his legal counsel.

6.9 Contract Time

Time is an important element in the performance of almost every construction project. Owners typically include a statement in the contract documents for a project, usually in the general conditions, which prescribes that time is of the essence in the performance of the construction contract. The AIA Document A201–2007, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction (Appendix D), contains the following provision: “Time limits stated in the contract are of the essence.”

The contract documents will contain a duration, usually stated as a number of days, which is stipulated to be the time within which the contractor must satisfactorily complete all of the requirements of the contract documents. If he fails to do so, he is subject to some very unpleasant consequences, usually in the form of liquidated damages, to be discussed in the next section.

When the contract declares that “time is of the essence,” this signifies that the stipulated completion date or time is considered to be essential to the contract and is an important element of the contractor's obligation. Failure by the contractor to complete the project within the time specified is considered to be a material breach of contract and is actionable by the owner.

Most construction contracts are explicit regarding construction time, designating either a completion date or a specific number of calendar days within which the work must be finished in compliance with the contract documents. The term calendar days including Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays is preferable, rather than the term working days. This language eliminates possible controversy concerning the effects of overtime, premium time, multiple shifts, and the like, when defining working days.

There also have been situations where the construction contract contains provisions whereby the contractor will receive a bonus for completing the contract ahead of schedule. Public agencies have sometimes used the early-completion bonus system where prompt completion of the project will be of special economic significance to the public. Private owners likewise have found that providing an incentive to the contractor for early completion of all of the requirements of the contract is, at times, of benefit to the owner.

When the duration, the contract time, is stated to be a given number of calendar days, the date on which the time begins is an important matter. Construction contracts usually state that the contract time shall begin on the date the contract is signed, or on the date the contractor receives a formal “notice to proceed” or “letter of intent” from the owner. These terms are defined in the sections that follow later in this chapter.

The contract typically establishes the contract completion date as being the date of the owner's issuance of the certificate of substantial completion. This document, and the accompanying procedures, are discussed in a subsequent section of this chapter. In general, substantial completion is related to the owner's capability of using the structure for its intended purpose, despite small defects to be corrected or minor items not yet accomplished—that is, substantial completion.

6.10 Liquidated Damages

Almost all construction projects are of such a nature that the owner will incur hardship, expense, or loss of revenue should the contractor fail to complete the work within the time specified by the contract. Where the contract makes time an essential part of the contract, failure on the part of the contractor to complete the project within that time is a breach of contract and can make the contractor liable to the owner for damages. The amount of such damages may be determined by agreement, or by litigation.

Compensatory damages of this sort are difficult to determine with exactness, and therefore in construction contracts it is common practice for the owner to provide that the contractor shall pay to the owner a fixed sum of money for each calendar day of delay in satisfactory completion. Most contracts provide that such delay damages run only to the date of substantial completion or beneficial occupancy, although some specify the date that the architect-engineer certifies the project to be complete.

This assessment against the contractor, known as liquidated damages, is used in lieu of a determination of the actual damages suffered. The word liquidated in this instance merely signifies that the precise amount of the daily damages to the owner has been established by agreement. An advantage to the use of a liquidated damage provision in a construction contract is the possible avoidance of subsequent litigation between the owner and the contractor regarding the amount of actual damages. Liquidated damages, when provided for by contract, are enforceable at law, provided they can be shown to represent a reasonable measure of the actual damages suffered. The courts have ruled that a liquidated damages clause in a contract prevents the owner from recovering its actual damages, even where the actual damages suffered by the owner could be shown to exceed the amount provided by the liquidated damages provision.

The owner deducts any liquidated damages from the sum that is due the contractor at the time of final payment. Typical values of liquidated damages appearing in construction contracts vary from a few hundred dollars to many thousands of dollars per calendar day for each day the contractor requires to reach the point defined as satisfactory completion of the contract.

When the project delay was the fault of both the owner and the contractor, the owner's recovery of liquidated damages is generally precluded. However, in construction, the contractor may still be liable for a portion of the delay. It is to be noted that a liquidated damage clause normally works only one way. It conveys no automatic right to the contractor to apply the provision in reverse for owner-caused delay.

It must be emphasized that the courts enforce liquidated damage provisions in construction contracts only when their amount represents a reasonable forecast of actual damages the owner would be expected to suffer upon breach, and when it is impossible or very difficult to compute or make an accurate estimate of actual damages. When it has been established that the amount was excessive and unreasonable, the courts have ruled that such payment by the contractor to the owner constituted a penalty and the owner received nothing, or owner recovery was limited to the actual damages. Punitive damages (those intended to punish) are not ordinarily recoverable for breach of contract. It may be noted that construction contracts specifically provide that the sum named is in the nature of liquidated damages and not a penalty.

6.11 Extensions of Time

During the life of a contract, there are often occurrences that cause delay or add to the period of time necessary to construct the project. Just what kinds of delays will justify an extension of time for the contractor depends on the language and provisions of the contract. An extension of time relieves the contractor from termination for default, or from the assessment of liquidated damages by the owner, because of failure to complete the project on time. In the complete absence of any clause that defines an excusable delay, the contractor can normally expect relief only from delays caused by the law, by the owner, by the architect-engineer, or by an act of God.

For this reason, construction contracts usually contain an extension-of-time provision that defines which delays are excusable. The provisions of such clauses are quite variable. Because an extension of time constitutes a revision to the original contract terms, it is formalized by a signed instrument, called a change order (discussed in Chapter 4) that constitutes a binding change to the contract.

The addition of extra work to the contract as formalized by a change order is a common justification for an extension of time. In this case, the additional contract time that is made necessary by the broadened scope of the work is negotiated at the same time the cost of the extra work is determined when the change order is formalized. Delay of the project caused by the owner or its representative is another frequent cause of contract-time extensions.

Many other circumstances arising from unforeseeable causes beyond the control of and without the fault or negligence of the contractor can contribute to late project completion. Contracts often list specific causes of delay deemed to be excusable and beyond the contractor's control. Certain causes are essentially of an undisputed nature, provided the contractor has exercised due care and reasonable foresight. These causes include flood, earthquake, fire, epidemic, war, riots, hurricanes, tornadoes, and similar disasters.

Other less spectacular causes of delay may or may not be defined as excusable delays in the contract. Included here are occurrences such as strikes, freight embargoes, acts of the government, project accidents, unusual delays in receiving ordered materials, and owner-caused delays. Language in the contract that the contractor deems unreasonable or untenable with regard to excusable delays must be given proper consideration by the contractor when he is making the decision as to whether to prepare a bid for the project or, if he has decided to submit a proposal, as an element of his consideration of risk when he prepares his bid or at the time when the contract is being negotiated.

As a general rule, claims for extra time are not considered when they are based on delays caused by conditions that existed at the time of bidding, and about which the contractor might be reasonably expected to have had full knowledge. Also, delays caused by failure of the contractor to anticipate the requirements of the work in regard to materials, labor, or equipment required usually do not constitute reasons for a claim for extra time. Normally, adverse weather does not justify time extensions unless it can be established that such weather was not reasonably foreseeable and was unusually severe at the time of year in which it occurred and in the location of its occurrence.

Previously discussed is the fact that on unit-price contracts actual quantities of work can vary from the architect-engineer's original estimates. Minor variations do not affect the time of completion stated in the contract. However, if substantial variations are encountered, an extension of contract time may very well be justified, and the contractor should promptly notify the architect-engineer, in writing, regarding the need for an extension of time.

Whenever a delay in construction is encountered over which the contractor has no control, the contractor must bring the condition to the attention of the owner and/or architect-engineer in writing within a designated period of time after the start of the delay. This time within which the contractor must let the architect-engineer know of his request for an excusable delay is called a notice provision and is typically specified in construction contracts. This communication should present specific facts concerning times, dates, and places and include necessary supporting data about the cause of delay. Failure by the contractor to submit a timely written request along with documentation within the notice period will typically seriously jeopardize the chances of obtaining an extension of time.

6.12 Acceleration

Acceleration refers to the owner's directing the prime contractor to accelerate its performance of the work so as to complete the project at an earlier date than the current rate of work advancement will permit. If the project has been delayed through the fault of the contractor, the owner can usually order the contractor to make up the lost time without incurring liability for extra costs of construction. However, if the owner directs acceleration under the changes clause of the contract, requiring that the work will be completed before the specified contract completion date, the contractor can recover under the contract change clause for the increased cost of performance, plus a profit.

There is another instance of acceleration, however, where additional costs may or may not be recoverable by the contractor. This is often referred to as constructive acceleration. Such a case occurs when the owner either fails or refuses to grant the contractor a requested extension of time and still insists that the project be completed by the original contract date. The owner's action in this case compels the contractor to accelerate job progress in order to comply with the original completion date. This obviously increases the contractor's costs of construction. In such an instance, the contractor must be able to demonstrate certain key elements before being granted relief from these additional costs. Along with this implicit directive to accelerate by the owner, there must have been an excusable delay for which the contractor had originally requested an extension of time, and this request must have been denied. In addition, the contractor must have completed the contract on time, and must be able to show that he actually incurred extra costs in so doing as the result of the decision by the architect-engineer and the owner to deny his request for additional time.

6.13 Differing Site Conditions

A “differing site conditions,” “changed conditions,” or “concealed conditions” clause in a construction contract refers to some physical aspect of the project or its site that differs materially from that indicated by the contract documents, or that is of an unusual nature and differs materially from the conditions ordinarily encountered. This includes unknown physical conditions of an unusual nature that differ materially from those ordinarily found to exist and are generally recognized as inherent in construction activity of the character provided for in the contract documents. The essential test is whether a given site condition is substantially different from that which the contractor should have reasonably expected and foreseen. Unexpected conditions resulting from hurricanes, floods, abnormal weather, or nonphysical conditions are not normally considered to be changed conditions.

The construction cost and time of many projects depend heavily on the proper analysis of local conditions at the site, conditions that cannot be determined exactly in advance. This applies particularly to underground work, where the nature of the subsoil and groundwater can have a significant influence on costs. At the time of bidding, the owner and its architect-engineer must make full disclosure of all information available concerning the proposed project and its site. The contractor uses the information as it sees fit and is responsible for its interpretation. The contractor is expected to perform its own inspection of the site and to make a reasonable investigation of local conditions.

The matter of who pays for the “unexpected condition” when it is discovered during construction of the project depends on the contract provisions, as well as on the exact nature of the different conditions which were encountered. Many disputes, and a great deal of arbitration and court action have resulted from claims of “unexpected conditions” or “unforeseen conditions.”

No implied contractual right exists for the contractor to collect for unforeseen conditions. Any ability to collect extra payment and additional time for changed conditions must be provided by the terms of the contract. An exception is made, however, when the drawings and specifications contain incorrect and misleading information. In such cases, the courts generally rule that the owner warrants the adequacy of the contract documents and that the warranty is breached where errors or defects are present.

Many contracts provide for an adjustment of the contract amount and time if actual subsurface or latent physical conditions at the site are found to differ materially from those indicated on the drawings and specifications or from those inherent in the type of work involved. Delay-related expenses resulting from differing site conditions are also considered to be compensable. This provision is often expressed as a “differing site conditions” clause, and its objective is to provide for unexpected physical conditions that come to light during the course of construction. When such a contract clause is present, the financial responsibility for unexpected conditions is placed on the owner. The AIA General Conditions of the Contract for Construction in Appendix D contains such a provision.

It is the purpose of a changed-conditions clause to reduce the contractor's liability for the unexpected, and to mitigate the need for the contractor's including large contingency sums in the bid to allow for the risk of possible serious variations in site conditions from those described and set forth by the contract documents.

It must be clearly understood at this point that in order for a claim to be sustained under this clause, the unknown physical conditions must truly be of an “unusual nature” and must differ “materially” from those ordinarily encountered and generally regarded as inherent in work of the character provided for in the contract. The essential question is whether the conditions are different from those the contractor should have reasonably expected and whether these conditions caused a significant increase in the project time or cost.

Various disclaimers and exculpatory clauses denying liability and responsibility for actual field conditions frequently appear in construction contracts. A common clause provides that neither the owner nor the architect-engineer accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of subsurface data provided, and that all bidders are expected to satisfy themselves as to the character, quantity, and quality of subsurface materials to be encountered. However, where a differing site conditions clause has been in the contract, and where such conditions were discovered, disclaimers of this kind have not acted as a bar to the contractor receiving relief under the clause.

Instances of such exceptions occur when the site conditions were deliberately or negligently misrepresented on the contract documents, when the owner did not reveal all of the relevant information it possessed or that it had knowledge of, or when there was a breach of warranty of the correctness of the bidding information. Disclaimer clauses have also been denied when they were deemed by the courts to be too severe, when they were in direct contradiction with other specific representations, and on the basis that it was unreasonable to expect the contractor to make an extensive investigation of underground conditions during the bidding period.

It must also be noted that, regardless of the contract wording, if differing site conditions are discovered at the site and if the contractor intends to claim additional cost or time, it must promptly notify the owner in writing, and must also keep detailed and separate cost records of the additional work involved. Failure to do so will very likely make it impossible for the contractor to prevail and to recover any damages.

6.14 Owner-Caused Delay

There are some instances in which the work on a construction project is delayed by some act of omission or commission on the part of the owner, or on the part of someone for whom the owner is responsible such as the architect-engineer, or other contractors. Examples are delays in making the site available to the contractor, failure to deliver owner-provided materials on time, unreasonable delays in approval of shop drawings, delays caused by another contractor, delays in issuance of change orders, and suspension of the work because of financial or legal difficulties. Additionally, some of the unaffected parts of the work can be prolonged or disrupted because of the discovery of changes or differing site conditions associated with other portions of the project.

Owner-caused delay is of concern to the contractor for two reasons. First, when the overall completion date of the project is affected, a suitable extension of time must be obtained. As a rule, contracts provide for extensions of time in the case of owner-caused delay, and this matter is seldom troublesome. The second and more difficult problem for contractors is the “ripple” effect of such delays, that is, the “consequential damages” or “impact costs” associated with unchanged work that can result from project delay. Examples of impact costs are standby costs of nonproductive workers, supervisors, and equipment; expenses caused by disrupted construction and material delivery schedules; start-up and stopping costs such as those incurred in moving workers and equipment onto and off of the job; and additional overhead costs.

It sometimes happens that work is delayed by owner-caused delays until the onset of conditions the contractor did not anticipate and that would not have influenced the project had the delay not occurred. Examples include the onset of cold weather, the rainy season, or the time of spring runoff, resulting in greatly increased operating costs. Owner-caused project delay can defer work until higher wage rates have gone into effect, until material prices have increased, or until bargains or discounts have been lost. Barring contractual provisions to the contrary, a contractor has the right to recover damages for its increased costs of performance caused by delays that are attributable to the owner.

Such claims are based on the owner's implied warranty that the drawings and specifications which the owner and the architect-engineer prepared and provided are adequate for construction purposes, and the implied promise that the owner and architect-engineer will not disrupt or impede the performance of the construction process. In order to recover damages, the contractor must prove the delays were caused by the owner and that the contractor was damaged as a direct result of the delays.

However, construction contracts may contain a variety of provisions concerning owner-caused delay. On federal projects the government has assumed responsibility for payment of the impact cost of changes and changed conditions as they affect unchanged work. Federal contracts and many others contain suspension-of-work clauses that provide for the contractor's recovery of the extra cost occasioned by owner-caused delay or suspension. However, by contrast, some contracts contain provisions that expressly limit contractor relief in cases of job delay, to time extensions only.

Many contracts, both public and private, contain “no-damage for delay” clauses whereby the owner is excused from all responsibility for damages resulting from owner-caused delay. Where such exculpatory or hold-harmless clauses are present, they are generally given effect by the courts, although they are strictly interpreted and limited to their literal terms. Exceptions that have allowed the contractor to collect increased costs are cases in which the delay was caused by active owner interference with the work, when the delay was of a type not contemplated by the parties, such as the owner not allowing the work to start on time, when the owner acted with malicious intent, when the delay resulted from bad faith or misrepresentation by the owner, when the delay was caused by owner failure to coordinate the work of other contractors on the site, when the delay was for an unreasonable period of time, or when the delay was caused by the owner's breach of a contractual obligation such as the nontimely delivery of owner-furnished materials. Even when consequential damages are awarded, they often reimburse the contractor for extra costs only, with no allowance for time-related additional costs, or for profit. It is to be noted that a few states have enacted statutes barring no-damage-for-delay clauses in construction contracts.

It is also noted that the contractor's careful review of all contract provisions, as recommended repeatedly in this text, would disclose clauses such as “no damages for delay.” The contractor can them make a determination with regard to whether or not he wishes to prepare a proposal for the project, or whether he is prepared to accept the risk which such a clause portends, if he enters a contract.

The contractor frequently is unable to recover delay damages because of an inability to prove the exact extent of the loss suffered. For this reason, when such a delay occurs, it is essential that the contractor keep careful and detailed records, and every element of supporting documentation, if it expects to recover extra costs from the owner. An additional point to be made is that many contracts require the contractor to notify the owner within a designated time after any occurrence that may lead to a claim for additional contract time or extra cost.

6.15 The Agreement

Although the agreement is defined and discussed in Chapter 4 as a typical element of the contract documents for a project, it is again included for reference here because of its obvious significance with respect to a construction project and also to present facts concerning this document within the context of important provisions and elements of the contract. The agreement is defined as a document specifically designed to formalize the construction contract between the owner and the construction contractor. It serves as a single instrument that brings together all of the contract documents by reference, and it functions for the formal execution of the contract.

The agreement serves the purpose of presenting a condensation of the elements of the contract documents, stating the work to be done and the price to be paid for it, and provides suitable spaces for the signatures of the parties. The agreement usually contains a few clauses that are closely akin to the provisions in the supplementary conditions, and which serve to amplify certain provisions that the owner and the architect-engineer may wish to emphasize. For example, it is common for the agreement to contain clauses that designate the completion time of the project, the fact that liquidated damages will be assessed for late completion and the amount of the liquidated damages. All of the elements that comprise the contract documents are typically listed, with a notation that each of these documents is incorporated by reference in the agreement. However, practice varies in this regard, with such clauses appearing sometimes in the supplementary conditions, other times in the agreement, and perhaps in both.

Standard agreement forms are normally used by both public and private owners, although on occasion the agreement may be especially prepared for a given project. Appendix G illustrates the use of AIA Document A101–2007, which is the agreement form that is often used by private owners for fixed-price building construction contracts. Document A101-2007 is designed for use with the AIA Document A201–2007, “The General Conditions of the Contract for Construction,” as contained in Appendix D. Appendix H reproduces AIA Document A102–2007, a form of agreement between the contractor and owner that is frequently used for cost-plus-fee contracts.

6.16 Letter of Intent

Occasionally, the owner may want the contractor to begin construction operations on the project before the formalities associated with the signing of the contract can be completed. However, the contractor must proceed with caution in such cases with regard to matters such as placing material orders, issuing subcontracts, or otherwise obligating itself before it has an executed and signed contract in its possession.

In cases where there is such urgency, and as a matter of protecting the interests of the contractor, it is common practice for the owner to authorize the commencement of work by the contractor with the owner's issuance of a letter of intent or letter contract. This letter is prepared for the signatures of both parties, and states their intent to enter into a suitable construction contract at a later date. When signed, the letter is binding on both parties, and furnishes the contractor with sufficient authority to proceed with construction in the interim, before the contract is formally executed. This interim authorization contains explicit information about settlement costs in the event the formal contract is not executed and will often limit the contractor to certain procurement and construction activities. The contractor should have his attorney examine a document of this kind before he signs such a letter of intent.

6.17 The Notice to Proceed

The beginning of contract time is usually established by a written notice to proceed, which the owner dispatches to the contractor. The date of its receipt, or a date stipulated in the notice to proceed is normally considered to mark the formal start of construction operations.

This notice, usually issued in the form of a letter, advises the contractor that it may enter the owner's site, and directs the contractor to commence work. The date of receipt of the notice to proceed, or the date that it stipulates as the date when the contractor is authorized to enter the site and to commence construction operations, also typically marks the beginning of project duration. Contracts usually require that the contractor shall commence operations within some specified period, such as 10 days, following his receipt of the notice to proceed.

6.18 Acceptance and Final Payment

The making of periodic payments by the owner as the work progresses does not necessarily constitute the owner's acceptance of the work. Construction contracts generally provide that acceptance of the contractor's performance is subject to the formal approval of the architect-engineer, the owner, or both. Most contracts provide that mere occupancy and use by the owner also do not necessarily constitute an acceptance of the work or a waiver of claims.

Acceptance of the project and final payment by the owner must proceed in accordance with the terms of the contract. Procedure in this regard is somewhat variable, although inspection and correction of deficiencies are the usual practice.

On building construction projects, the contractor will normally advise the owner or architect-engineer when substantial completion has been achieved. An inspection is held and a list of items, called a punch list, requiring completion or correction is compiled. Usually the architect-engineer issues a “certificate of substantial completion” at the time of his completion of a reinspection after punch list items have been corrected or completed. This action by the architect-engineer certifies that the owner can now occupy the project for its intended use. A provision appearing in many contracts is that upon substantial completion, the contractor is entitled to be paid up to a specified percentage of the total contract sum (95 percent is common), less such amounts as the owner may require to cover remedial work required by the punch-list items plus unsettled claims and a contingency reserve. The certificate of substantial completion also serves other purposes including shifting the responsibility for maintenance, heat, utilities, and insurance on the structure from the contractor to the owner. After the contractor has attended to the deficiency list, a final inspection is held and a final certificate for payment is issued. A common contract provision is that final payment is due the contractor within 30 days after substantial completion. This is applicable, however, only with consent of the surety and provided all work has been completed satisfactorily and the contractor has provided the owner with all required documentation. Final payment includes all retainage still held by the owner.

A legal question that frequently arises concerning final acceptance and payment involves the degree of contract performance required of the contractor. The modern tendency is to look to the spirit and not the letter of the contract. The vital question is not whether the contractor has complied in an exact and literal way with all of the precise terms of the contract, but whether it has done so substantially. Substantial completion may be defined as accomplishment by the contractor of all things essential to fulfillment of the purpose of the contract, although there may be inconsequential deviations from certain terms. Appendix D defines substantial completion as the stage at which the work (or designated portion thereof) is sufficiently complete that the owner can occupy or utilize the work for its intended purpose.

Certainly, the substantial performance concept does not confer on the contractor any right to deviate freely from the contractual undertaking, nor to substitute materials or procedures that it may consider equivalent to those actually called for by the contract. Only if defects are purely unintentional and not so extensive as to prevent the owner from receiving essentially what was contracted for, does the principle come into play.

6.19 Termination of the Contract

While the contract documents provide that the construction contract may be ended in a variety of ways, by far the most commonplace method of contract termination is satisfactory fulfillment of all contractual obligations on the part of both parties. However, there are other means of bringing a contract to an end that are of interest and importance to the construction industry. The conditions of the contract will typically contain a section or an article that defines reasons for, and methods of, termination of the contract. Some of the common reasons are discussed in the paragraphs that follow.

Material breach of contract by either party can be a cause for contract termination. Failing to make prescribed payments to the contractor or causing unreasonable delay of the project are probably the most common breaches by the owner. Other possible breaches could be failure or delay in performance, failure to coordinate the work, failure to provide the project site, or financial insolvency of owner. In such circumstances, the contractor is entitled to damages caused by the owner's failure to carry out its responsibilities under the contract.

Default, or failure to perform under the contract, is the usual breach of contract committed by contractors. Nonperformance, faulty performance, failure to maintain reasonable progress, failure to meet financial obligations, persistent disregard of applicable laws or instructions of the owner or architect-engineer also are examples of material default by contractors that convey to the owner a right to terminate the contract. When the owner terminates the contract because of breach by the contractor, the owner is entitled to take possession of all job materials and to make reasonable arrangements for completion of the work. It is worthy of note that when failure to complete a project within the contract time is the breach involved, the owner probably will not be awarded liquidated damages if he terminates the contract and does not allow the contractor to finish the job late when the contractor is making a genuine effort to complete the work. The legal record is subject to variation on this point, however.

A third way in which a contract can be terminated is by mutual agreement of both parties. This is not common in the construction industry, although there have been instances. For example, it sometimes happens that the contractor faces unanticipated contingencies such as financial reverses, labor troubles, or loss of key personnel that make proper performance under the contract a matter of considerable doubt. Under such circumstances, both the owner and the contractor may agree to terminate the contract and for the owner to engage another contractor. When little or no work has been done, termination of the contract by mutual consent can sometimes be attractive to both parties.

Construction contracts, particularly those that are publicly financed, normally provide that the owner can terminate the contract at any time it may be in its best interests to do so by giving the contractor written notice to this effect. When such a provision is present, the contractor has agreed to termination at the prerogative of the owner. However, in such an event, the contractor is entitled to payment for all work done up to that time, including a reasonable profit, plus such expenses as may be incurred in canceling subcontracts and material orders and in demobilizing the work. If the owner terminates the contract capriciously, it may become liable for the full amount of the contractor's anticipated profit, plus costs.

A contract may also be terminated because of impossibility of performance under circumstances beyond the control of either party. Impossibility of performance is not the case when one party finds it an economic burden to continue. To be grounds for termination of a contract, it must indeed be impossible or impracticable to proceed. For instance, unexpected site conditions may be found that make it impossible to carry out the construction described by the contract. Operation of law may render the contract impossible to fulfill. However, the doctrine of impossibility does not demand a showing of actual or literal impossibility. Impossibility of performance has been applied to cases in which, even if performance were technically possible, the costs of performance would have been so disproportionate to that cost reasonably contemplated by the contracting parties as to make the contract totally impracticable in a commercial sense. The deciding factor was that an unanticipated circumstance made performance of the contract vitally different from what was reasonably to be expected.

Other unusual, but possible, causes of contract termination can occur, such as destruction of subject matter. An example would be a contract to remodel an existing building that was destroyed by fire before the renovation was started. Frustration of purpose also can occur. To illustrate, a contract was awarded for the construction of a boat pier on a lake. Before the pier could be built, however, the lake was permanently drained.

6.20 The Warranty Period

Many construction contracts obligate the contractor to make good all defects brought to its attention by the owner during some warranty period after either the time of substantial completion or final acceptance, the point at which the period begins being variable with the form of contract. One year is a commonly specified warranty period, although periods of up to five years are sometimes required on certain categories of work, such as utility construction. During the specified warranty period the contractor is required, on notice, to make good at its own expense defects detected during this period. In most cases, the prescribed warranty period fixes the reasonable time and releases the contractor from further responsibility after its expiration. Warranty periods required by the contract are normally covered by the performance bond, and they do not operate to defer final payment.