Chapter 1

The Construction Industry

1.1 Introduction

The construction industry is very large by any standard, and it can be described and defined in a number of different ways. This chapter will begin to characterize the industry in terms of its size and economic impact, and will proceed to define by name and by function some of the practitioners who perform their professional work in the industry. Also to be examined are terminology relative to types of contracts, public and private; single and separate contracts; competitive bid and negotiated contract formation; different project delivery methods; different types of construction contractors; and various types or categories of construction projects. All of these are vantage points from which the construction industry can be observed, and all of these terms provide descriptors for various aspects of the professional practice of construction contracting in the industry.

1.2 The Construction Project

Humans are compulsive builders who have demonstrated throughout the ages a remarkable and continually improving talent for construction. As knowledge and experience have increased, the ability of humankind to build structures of increasing size and complexity has expanded enormously. In the modern world, everyday life is maintained and enhanced by an impressive array of construction of all kinds, awesome in its diversity of form and function. Buildings, highways, tunnels, pipelines, dams, docks, canals, bridges, airports, and a myriad of other structures are designed and constructed so as to provide us with the goods and services we require. As long as there are people on earth, structures will be built to serve them.

Construction projects are complex and time-consuming undertakings. The structure to be built must be designed in accordance with applicable codes and standards, culminating in working drawings and specifications that describe the work in sufficient detail for its accomplishment in the field. The building of a structure of even modest proportions involves many skills, numerous materials, and literally hundreds of different operations. The assembly process must follow a certain order of events that constitutes a complicated pattern of individual time requirements and sequential relationships among the various segments of the structure.

Each construction project is unique in its own way, and no two are ever quite alike. Each structure is tailored to suit its environment, designed and built to satisfy the needs of its owner, arranged to perform its own particular function, and designed to reflect personal tastes and preferences. The vagaries of construction sites and the infinite possibilities for creative and utilitarian variation of the structure, even when the building product seems to be standardized, combine to make each construction project a new and unique experience. The designer produces a design for each project to meet the needs of the owner within the constraints of the owner's budget. The contractor sets up a production operation on the construction site and, to a large extent, custom-builds each project.

The construction process is subject to the influence of numerous highly variable and often unpredictable factors. The construction team, which includes various combinations of contractors, owners, architects, engineers, consultants, subcontractors, vendors, craft and management workers, sureties, lending agencies, governmental bodies, insurance companies, and others, changes from one project to the next. All of the complexities inherent in different construction sites, such as subsoil conditions, surface topography, weather, transportation, material supply, utilities and services, local subcontractors, and local labor conditions, are an innate part of the construction project.

As a consequence of the circumstances noted above, construction projects are typified by their complexity and diversity, and by the nonstandardized nature of their design and construction. Despite the use of prefabricated units in certain applications, it seems unlikely that field construction can ever completely adapt itself to the standardized methods and the product uniformity of assembly-line production.

1.3 Economic Importance

For a number of years, construction has been the largest single production industry in the American economy. It is not surprising, therefore, that the construction industry has a great influence on the state of this nation's economic health. In fact, construction is commonly regarded as the country's bellwether industry. Times of prosperity are accompanied by a high national level of construction expenditure. During periods of recession, construction is depressed, and the building of publicly financed projects is often one of the first governmental actions taken to stimulate the general economy. When the construction industry is prospering, new jobs are created, both in direct employment in construction, as well as in related industries, such as materials and equipment manufacturing and supply. A high level of construction activity and periods of national prosperity are simultaneous phenomena; each is a natural result of the other.

Some facts and figures pertaining to construction in the United States are useful in gaining insight into the tremendous dimensions of this vital industry. The total annual volume of new construction in this country at the present time is approximately $1.75 trillion. The annual expenditure for construction normally accounts for about 10 percent of the dollar value of our gross domestic product. Approximately 80 percent of construction is privately financed, and 20 percent is paid for by various public agencies. The U.S. Department of Labor presently indicates that construction contractors directly employ more than 7 million workers during a typical year. If the production, transportation, and distribution of construction materials and equipment are taken into account, construction creates, directly or indirectly, about 12 percent of the total gainful employment in the United States.

1.4 The People Involved on a Construction Project

Construction projects are designed and built through the combined efforts of a number of people. Each has a defined role and a set of accompanying responsibilities in the total effort. These roles, as well as the rights and responsibilities of those who participate in the process, are defined in contracts that are formed between the various participants.

While the construction industry is often described in terms of materials, such as concrete, steel, masonry, and many others, or in terms of project delivery systems and contracting methods, it can also be typified in terms of the people who interact in the process which results in a completed project. It is the people who are involvd in the design and construction of a project who bring the project to fruition. Construction contracting can therefore best be characterized as a people-oriented business and profession.

1.4.1 Owner

The owner is the central figure in any construction project. The owner can be defined most directly as the person who will own—literally will have title to—the project upon its completion. The owner is also the person who will pay for the design and construction of the project.

It is the owner who initiates all that will follow in the design and construction processes. The inception of any construction project begins with the owner's recognition of a need for a constructed project, whether it be a new building or an expanded or renovated building or a facility such as a highway, industrial plant, or airport. Most owners perceive this need and refine its ramifications over a period of time, until at some point the decision is made to move forward with the idea.

Typically, the owner will next think in terms of financing—how much money he is willing or able to commit to satisfy this need. Additionally, the source of these funds is considered and analyzed. Determinations are made regarding whether the forthcoming project will be funded with owner's funds or with borrowed capital. Most owners will make at least a preliminary determination during the course of this process, with regard to the maximum number of dollars the owner is willing or able to spend for the design and construction that will satisfy the need that has been perceived. This value will become the owner's budget for the project.

Most owners will next seek the services of a design professional—an architect or engineer. The owner will look to this person to assist with defining and codifying, in detail, what the owner's needs are. Then the owner will expect the designer to produce a design that will satisfy the needs of the owner, within the constraint of the owner's budget.

Various methods are employed by owners to determine who the designer will be. The owner may have a familiarity, or a history of past performance, with a certain designer or design firm. Alternately, the owner may seek input from peers and acquaintances regarding competent design firms. Sometimes, the owner may stage a design competition, whereby he sets forth the parameters of his need, and invites design professionals to submit designs in competition with one another for selection by the owner to design the project. These and other methods of the owner's choosing the firm that will produce the design are further discussed later in this book.

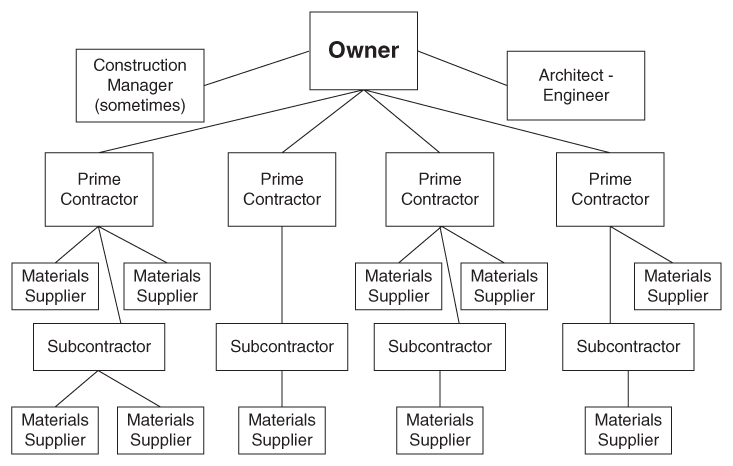

It is important to note that the owner will select a design firm and then will enter a contract with that firm. The contract will set forth the exact nature of the services that the designer will provide, and will contain provisions relative to determination and payment of the designer's fees, along with defining all of the administrative elements of the agreement between these parties, as well as the rights and obligations of the two parties. The existence of an actual contract between two parties is referred to as their having privity of contract with each other. The concept of who has privity of contract with whom on a typical construction project is further discussed in succeeding sections of this chapter. Likewise, details regarding the typical content of the contract between the owner and the designer will be further discussed in another chapter. The most common relationship between the owner and the architect-engineer, as well as the names of the other parties most commonly involved in the design and construction of a project, and who has privity of contract with whom, are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 People Involved and Hierarchy of Contracts on a Typical Building Construction Project

Owners may be characterized as being private owners or public owners, and the construction projects that are designed and constructed for them are described in the same terms. Private owners may be individuals, partnerships, or corporations. The funds that are used to pay for the design and construction of the project are private funds, that is, not public or government funds. Most private owners have structures built for their own use: business, habitation, pleasure, or otherwise. However, some private owners do not intend to become the end users. Such owners intend that the completed structure is to be sold, leased, or rented to others.

Public owners are defined as some level of government—national, state, county or parish, municipal, or school district—or some agency or department of government. Public owners range from agencies of the federal government down through state, county, and municipal entities, to a multiplicity of local boards, commissions, and authorities. Construction projects that are designed and constructed for public owners are defined as public projects. Such projects are paid for by appropriations, bonds, tax levies, or other forms of public funding, and are designed and built to meet some defined public need. Public owners are required to proceed in accordance with applicable statutes and administrative directives pertaining to all aspects of the design and construction process.

Most owners relegate by contract the design of their projects to professional architecture or engineering design firms, and award contracts for the construction of their facility to construction contractors. However, there are some owners who, for various reasons, elect to play an active role in the design and/or the construction of their projects.

For example, some owners perform their own design, or at least a substantial portion of it. In similar fashion, some owners choose to act as their own construction managers or perhaps even to perform their own construction. Many industrial and public owners have established their own construction organizations that work actively and closely with the design and construction of their projects. These concepts are further discussed in other sections of this chapter.

1.4.2 The Architect-Engineer

The designer or design firm, also known as the design professional, is the party, organization, or firm that designs the project. Both architects and engineers are licensed design professionals. Because the design of facilities is architectural or engineering in nature, and is often a combination of both, the term architect-engineer is used in this book to refer to the primary design professional, regardless of the applicable specialty or the relationship between the designer and the owner.

The architect-engineer can occupy a variety of positions with respect to the owner for whom the design is produced. The traditional and most common arrangement is one in which the architect-engineer is a private and independent design firm that produces the project design by the terms of a contract between the owner and the architect-engineer. Appendix B, AIA Document B101–2007, “Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Architect,” provides an example of a typical contract that might be entered between the owner and an architect, as written by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which is the primary national professional association for architects.

Many public agencies and large corporate owners maintain their own in-house design capability. In such instances, the architect-engineer is a functional part of the owner's organization. In other instances, the owner contracts with a single party for both design and construction services, in an arrangement referred to as design-construct or design-build. In this arrangement, the architect-engineer is a branch of, or is affiliated in some way with, the construction contractor.

There are also arrangements where large industrial firms have chosen to reduce their in-house design staffs and have established permanent relationships with outside architect-engineers. Such “corporate partnerships” call on the architect-engineer to provide a broad range of design, engineering, and related services on an open-ended basis. Such arrangements are said to work to an owner's advantage by fostering a team approach and reducing litigation between the parties.

1.4.3 Engineering Consultants

As was noted in the previous section, construction projects have an architect or an engineer as the primary designer. Typically, a variety of engineering consultants are called upon by the primary designer to input their expertise into the design effort for certain elements of the design. If the primary designer for a building construction project is an architect, a civil engineer will typically provide services for site work, drainage, and streets and driveways; a structural engineer may be retained to perform design and analysis on the structural system for the building, or on individual structural members; a mechanical engineer may design or assist with the design of heating, ventilating, and air conditioning equipment or systems in the building. Other engineers may be called upon to provide oversight or specific assistance with other aspects of the building design, as well.

These engineers typically enter a contract with the primary designer for the provision of their assistance and are typically paid by the primary designer. In other instances, the owner may contract with engineering consultants, whose work then provides input to the design. A typical example in building construction is the owner's providing geotechnical engineering services, whereby the soils at the site are sampled, analyzed, and tested, and where the geotechnical engineer provides both soil investigation and testing information and, frequently, his professional recommendation regarding the type of foundation system that will be suitable for the building to be designed. This information then is made available to the building design architect or engineer who will design the foundation.

1.4.4 Other Consultants

In the same fashion as noted previously, a variety of consultants may be utilized by the primary designer or by the owner to provide their expertise with specific portions of the design. Examples include lighting consultants, acoustical consultants, and the like.

1.4.5 Construction Manager

The construction manager is a professional who enters a contract with the owner, and by the terms of that contract provides a variety of different services to the owner. The concept of construction management became part of the design and construction process some years ago at a time when design-bid-build was the predominant project delivery method, whereby owners entered contracts with architect-engineers to produce the design, and contractors then submitted bids or proposals with their prices for constructing that which was designed, with one of the bidding contractors then selected for a construction contract to build the project. A number of owners saw value within this process in entering a contract with a third party to represent the owner's interests in the owner's contract with the architect-engineer and in his contract with the construction contractor. Construction management contracts were utilized when the concept originated and continue to be used today, in both the single-contract system and in the separate-contracts system. These methods of contracting are discussed more fully in subsequent sections of this chapter.

As the use of construction management contracts has continued and evolved, a variety of different services have come to be included in these contracts. The fact that the concept has endured and has evolved into several variations is indicative of the fact that owners have recognized, and are willing to pay for, a series of services beyond those defined in traditional historical design contracts and construction contracts.

Construction management services may be performed by design firms, contractors, and professional construction managers. Such services range from providing professional advice and counsel to the owner, to coordinating contractors during the construction phase, to broad-scale responsibilities over project planning and design, design document review, construction scheduling, value engineering, cost monitoring, and other management services. The demand for construction management services has increased greatly in recent years as owners have identified new needs, financial approaches, and construction technologies. Selection of the construction manager by the owner is sometimes accomplished by competitive bidding, using both fee and qualifications as the basis for contract award. In the usual instance, however, the construction management contract is considered to be a professional services contract and is negotiated. These contracts usually provide compensation for the construction manager on the basis of a fixed fee or percentage of construction cost, plus reimbursement of management costs.

As the construction management concept has evolved, construction management has come to be defined in two basic variations: construction management agency (CMA) and construction management at risk (CMAR). In the construction manager as agent arrangement, the construction manager enters a contract with the owner, and by the terms of that contract, he represents the owner's interests in the owner's contracts with the architect-engineer and with the prime contractor(s). The construction manager has no contractual relationship with the architect-engineer or with the general contractor(s); he provides his counsel and assistance to the owner, and the owner then decides whether to take action. The construction manager as agent is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Construction Manager as Agent in Single- and Separate-Contracts Systems

In the CMAR contract form, the construction manager enters a contract with the owner whereby he has the responsibility for completing the construction project on time, at or under the stipulated price or the guaranteed maximum price. Often, this form of construction management contract is written by the owner in such a way that the construction manager can also provide consulting services to the owner during design, and the construction manager may actually assist the owner in the selection of the design firm.

In CMAR, the construction manager effectively acts as the general contractor during construction. The CMAR contract form may be utilized in both the single- and separate-contracts systems, as noted in Figure 1.3, and may also be used in the design-build method of project delivery, which is discussed in a subsequent section of this chapter. Thus, the construction management firm frequently has responsibility for delivery of the project to the owner, from the onset of design through final completion of the project.

Figure 1.3 Construction Manager at Risk in Single- and Separate-Contracts Systems

At the present time, construction management (CM) is extensively utilized in this country by both private and public owners. During its early evolutionary period, confusion existed as to just what the duties and responsibilities of the CM were, what type of business firm was best qualified to perform such services, and how traditional construction relationships and responsibilities would be changed when the system was used. Some problems arose early, following the introduction of the construction management concept, concerning the lack of a practical code of ethics and standards of practice, uncertainty about liabilities of the participants, and the absence of standard contract documents to cover the wide range of CM services being provided by engineers, architects, contractors, and other parties. However, time and experience have served to stabilize this form of construction project delivery.

The Construction Management Association of America (CMAA) is a professional association which has, since its inception, been engaged in developing an accepted professional identity for construction managers and uniform standards for CM practice. In 1986, the CMAA published its standards of practice for construction managers. These standards serve as a guide to CM services and propose criteria for, and measurements of, a construction manager's performance. They describe the component elements of CM practice and define the scope of CM services. CMAA has also developed a series of standard CM contract documents.

1.4.6 The Prime Contractor

The prime contractor is defined as a business firm that has a contract with the owner for the construction of a project, either for the entirety of the project or for some stipulated portion thereof. As defined previously, the prime contractor thus has privity of contract with the owner.

While they are referred to in the context of contract formation as the prime contractors, in business practice these contractors refer to themselves by a variety of names. Many choose the term general contractor to indicate that they are generalists in construction practice, interested in and capable of performing different kinds of projects. Other prime contractors identify themselves in terms of the kind of work they prefer to perform, and take on names such as highway contractors, heavy construction contractors, building contractors, residential contractors, and so on. These various types of construction contracting will be defined and discussed in subsequent sections.

On most construction projects, there is one prime contractor. This contracting arrangement is referred to as the single-contract system. In this system, the prime contractor is that party who brings together all of the diverse elements and inputs of the construction process into a single, coordinated effort. The single prime contractor and single-contract system will be discussed in more detail in subsequent sections of this chapter.

The essential function of the prime contractor is management control and coordination of the entire construction process. Ordinarily, this contractor is in complete and sole charge of the field operations on a project, including the procurement and provision of necessary construction labor, materials, and equipment, and the management of the entirety of the construction process. Additionally, the prime contractor will usually enter contracts with a number of subcontractors, who will perform portions of the work on the project and will be responsible for managing and coordinating their work on the project.

The chief contribution of the prime contractor to the construction process is the ability to marshal and allocate and manage all of the resources required for construction of the project in order to achieve completion at maximum efficiency of time and cost. A construction project presents the contractor with many difficult management problems. The skill with which these problems are met determines, in large measure, how favorably the contractor's efforts serve its own interests as well as those of the project owner.

1.4.7 The Subcontractor

A subcontractor is a construction firm that contracts with a prime contractor, that is, has privity of contract with the prime contractor for the performance of a stipulated portion of the work on a project. Subcontractors are also frequently referred to as specialty contractors.

Economic facts, along with the increasing complexity of construction projects, as well as the efficiencies inherent in having specialized contractors performing segments of the work on a project, have confirmed the subcontract system to be an efficient and economical resource for use on construction projects of all kinds. The operations of the average general contractor are not always sufficiently extensive to afford full-time employment of skilled craftsmen in each of the numerous trade classifications and specialties needed to complete the work in the field. With the advent of subcontracting, these contractors are able to keep only a limited number of full-time employees on their payroll and then can award subcontracts for the performance by a specialist of the numerous specialty crafts as the need arises.

By subcontracting, the prime contractor can obtain workers with the requisite skills when they are needed, without the necessity of maintaining an unwieldy and inefficient full-time labor force for all of the numerous and specialized crafts which are needed on construction projects today. Subcontracting firms are able to provide substantially full-time employment for their workers, thereby affording an opportunity for the acquisition and retention of the most highly skilled and productive construction tradesmen. Additionally, these skilled craftsmen and the subcontracting companies that employ them bring with them the equipment, tools, and instrumentation necessary for the specialized elements of many projects. Qualified subcontractors are usually able to perform their specialty work more quickly and at a lower cost than a general contractor could. It can also be argued that those people and the companies that employ them, who perform their specialty work on construction projects day after day, can consistently complete their work at a higher level of quality. Many of the construction specialties that are typically performed by subcontractors, such as electrical work and plumbing work, have particular licensing, bonding, and insurance requirements.

How much of the work the prime contractor decides to self-perform on the projects that he constructs, and how much of the work he performs by awarding subcontracts for the remaining elements, depends on the nature of his management plan the nature of his business organization, and the type of construction involved. There are instances where all of the work on a project is subcontracted, with the prime contractor providing only supervision, overall project coordination and management, and perhaps general site services. Contractors who perform construction projects in this manner are sometimes referred to as broker contractors. At the other end of the spectrum are those projects where the general contractor does no subcontracting, choosing to self-perform the entire work with its own forces.

This occurrence is extremely uncommon today on building construction projects, although in other types of construction this practice is still followed. In the usual case, however, the prime contractor will perform some of the operations that comprise the work on the overall project and will subcontract the remainder to various specialty contractors.

When the prime contractor engages a specialty firm to perform a particular portion of the overall construction project, the two parties enter into a contract called a subcontract agreement or simply a subcontract. This subcontract agreement will pass through to the subcontractor many of the responsibilities that the prime contractor has agreed to fulfill to the owner and will stipulate the exact services the subcontractor is to provide and specific elements of the work that the subcontractor is to perform.

It should be noted that a subcontract agreement between a prime contractor and a subcontractor in no way establishes a contractual relationship between the owner and the subcontractor. The prime contractor, by the terms of its contract with the owner, assumes complete responsibility for the direction and control of the entire construction project. An important part of this responsibility is coordinating and supervising the work of the subcontractors. When the general contractor subcontracts a portion of the work, this contractor remains completely responsible to the owner for the total project and is liable to the owner for any negligent performance of the subcontractors. However, the courts have ruled that, in the absence of provisions in the general contract holding the prime contractor responsible for the negligence of its subcontractors, the contractor cannot be held liable for damages caused by the collateral torts of its subcontractors.

In private construction, the prime contractor generally decides how much of the work on a project he will self-perform with people on his payroll and under his direct supervision, and how much of the work he elects to perform by subcontracting. However, on some private construction projects and frequently on public construction projects, the owner imposes a limitation on the proportion of the total construction on the project that the prime contractor is allowed to subcontract. For example, several federal agencies have set such limitations. Additionally, some states have established statutory restrictions on the subcontracting of public works in those states. Such limitations on construction subcontracting are intended to circumvent any of a number of potential problems associated with extensive subcontracting. An extensive number of subcontracts on a project can lead to problems such as division of project authority, fragmentizing responsibility, complicating the scheduling of job operations, adding to the difficulties of coordinating construction activities, weakening communication between management and the field, fostering disputes, and generally impeding to job efficiency. Obviously, the extent to which these difficulties may actually occur is very largely a function of the experience, organization, and management skill of the prime contractor involved.

1.4.8 The Sub-subcontractor

A sub-subcontractor is one who enters a contract with a subcontractor on a project for the performance of a stipulated portion of the subcontractor's work. Sub-subcontractors may be engaged when a subcontractors is not capable of, or may not be interested in, performing all of the work in its scope of work as defined in the subcontract agreement with the prime contractor. While sub-subcontracting is sometime performed, for the same reasons described in the preceding paragraphs, many owners limit whether and to what extent sub-subcontractors may be utilized on a project. In the same way, many prime contractors include language in their subcontract agreements limiting sub-subcontracting on the part of subcontractors.

1.4.9 Vendors

Vendors, also referred to as materials suppliers, are those who provide materials or products for inclusion in a project. They do not provide services or labor for the installation of the materials in a project, and furnish only materials or other products. They generally do so by the terms of a sales contract, purchase order, or purchase agreement that they enter with a prime contractor, subcontractor, or sub-subcontractor.

1.5 Construction Categories

The field of construction is as diversified as the uses and forms of the many types of the end products that it produces. While the several types and categories of construction can be classified in different ways, construction is commonly divided into four main categories: residential construction, commercial construction, heavy/civil/highway construction, and industrial construction. It should be noted, however, that some of these categories may be subdivided and described in other terms, and also that there is some overlap among these divisions and that certain projects do not fit neatly into any one of them.

In general, contracting firms tend to specialize with regard to the types of work they perform, and therefore typically perform most of their work within one of these divisions or one of the subdivisions to be described later. This specialization is usual and necessary because of the radically different equipment requirements, construction methods, trade and supervisory skills, contract types and provisions, and financial arrangements involved with the different construction categories. The four main divisions—residential, commercial, heavy/civil/highway, and industrial—are further described in the following paragraphs.

1.5.1 Residential Construction

Residential construction, also referred to as housing, includes the building of residences of all kinds. Included in this category are those who build single-family homes; duplexes; condominiums; multiunit townhouses; low-rise, garden-type apartments; and high-rise apartments. Design of this construction type may be performed by the owners themselves, by architects, or by the builders themselves. Although a number of very large national residential building firms are engaged in various forms of residential construction, this category of construction is dominated by small building firms.

Residential construction typically accounts for about 40 to 50 percent of new construction during a typical year. Historically, residential construction has been characterized by instability of market demand and is strongly influenced by governmental regulation and national monetary policy. Residential construction is also an area of construction typified by periodic high rates of contractor business failures.

A significant proportion of housing construction is financed through private financial lending institutions, while government or quasi-government agencies, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, or “Fannie Mae”), the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA, or “Ginnie Mae”), and Veterans Affairs (VA), also provide mortgage financing or mortgage guarantees for residential construction.

Within this category, some residential contractors are speculative builders and others are custom builders, while some residential contractors construct both speculative and custom units. Speculative builders are those who construct a residential building in the role of owner-builder. They acquire real estate and a design for a residence, and then they build the facility and offer it for sale. Their business plan is to sell the property to a new owner during, or soon after completion of, the construction.

Custom residential builders are those who construct a residence for an owner by the terms of a contract between the owner and the builder. The owner will typically own the real estate on which the residence will be built, and usually the owner will have obtained a design for the facility to be constructed, either from the builder, from an architect, or from some other source.

1.5.2 Commercial Construction

Commercial construction in the commonly understood sense includes buildings constructed for institutional, educational, light industrial, business, social, religious, governmental, and recreational purposes. Some refer to the construction of churches and schools within this category as institutional construction.

Design of the buildings in this construction category is performed predominantly by architects, with engineering design services and consulting services being obtained by the architect for input to the design as needed. Construction of this kind is generally performed by prime contractors or construction managers who typically subcontract substantial portions of the work to specialty firms. Both the single- and separate-contracts systems may be used.

Contractors who perform commercial construction typically refer to themselves as building contractors or as general contractors. In normal business years, private capital finances most commercial construction, which normally accounts for 20 to 30 percent of the annual total volume of new construction.

1.5.3 Heavy/Civil/Highway Construction

Almost all of the facilities described with these terms are designed by an engineer, rather than by an architect, and therefore construction of this kind is often broadly referred to as engineered construction. This category includes those structures whose design usually is concerned more with functional considerations than aesthetics and involve field materials such as earth, rock, steel, asphalt, concrete, timbers, and piping. Engineered construction is also characterized by the utilization of numerous major items of construction equipment, and projects of this type are characterized by large spreads of this equipment, such as power shovels, tractor-scrapers, pile-drivers, draglines, large cranes, heavy-duty haulers, paving plants, rock crushers, and associated equipment types.

In a general sense, heavy construction typically includes the design and construction of facilities such as power plants, dams, levees, freshwater treatment plants, wastewater treatment plants, desalinization plants, aqueducts, flood control structures, canals, railroads, airports, tunnels, port and harbor facilities, and the like. Most people would use the term civil construction to describe the design and construction of water, gas, and electrical utility lines; telephone distribution facilities; streets; curbs and gutters; storm drains; and so on. Highway and airfield construction refers to clearing, excavation, fill, aggregate production, sub-base and base, paving, drainage structures, bridges, traffic signs, lighting systems, and other such items commonly associated with this type of work.

It should be noted that the distinctions between the categories of engineered construction described earlier are not exact. There is a considerable amount of overlap, and some contractors who perform these types of work may refer to themselves with different identifying labels. For example, some highway contractors would routinely include the construction of bridges within their scope of work. Others might award bridge construction to separate contractors or to subcontractors, while some other contractors specialize in the construction of bridges as their primary business. Similarly, some municipal storm drains might be constructed by contractors who refer to themselves as heavy construction contractors, while others performing similar work might call themselves civil construction contractors.

Most engineered construction projects of the kind described here are publicly financed, and therefore are also frequently characterized as public construction projects. Projects of the kind described in this section in the aggregate account for approximately 20 to 30 percent of the new construction market.

1.5.4 Industrial Construction

Industrial construction includes the erection of projects that are associated with the manufacture or production of an industrial product or service. Such structures are frequently highly specialized and highly technical in nature, and are typically built by large, specialized contracting firms that perform both the design and field construction. Typical examples of this type of construction are petroleum refineries and process plants of all kinds. Almost all of this type of construction is designed by engineers rather than by architects. In addition to an engineer producing the primary design, other engineering firms, and sometimes a variety of consulting firms, assist with specific elements of the design.

While this category accounts for only 5 to 15 percent of the annual volume of new construction, it includes some of the largest projects built. In the United States, a very large proportion of this category of construction projects is privately financed.

1.6 Project Financing

1.6.1 By Owner

As noted in a previous section, the owner makes the necessary financial arrangements for the construction of most construction projects. This normally requires obtaining the funding from some external source. In the case of public owners, the necessary capital may be obtained by tax revenues, appropriations, or bonds. A large corporate firm may obtain the funds by the issuance of its own securities, such as bonds. For the average private owner, funding is normally sought from one of several possible loan sources, such as banks, savings-and-loan associations, insurance companies, real estate trusts, or government agencies.

Where construction funding is obtained by commercial loans, the owner must typically arrange two kinds of financing: (1) short-term financing, also referred to as interim financing, or as construction financing, to pay the construction costs; and (2) long-term financing, also referred to as mortgage financing, which is repaid over a longer term. The short-term financing involves a construction loan and provides funds for land purchase and project construction. The term of a construction loan usually extends only for the construction period and is typically granted by a lending institution with the expectation that it will be repaid at the completion of construction by some other loan such as the mortgage financing. The term of the mortgage loan is usually for an appreciable period such as 10 to 30 years. Usually, the first objective of the project owner is to obtain the commitment for the long-term or permanent financing from a lender. Once this commitment is arranged, the construction loan is then typically arranged.

When the mortgage lender has approved the long-term loan, a preliminary commitment is issued. Most lenders will not give the final approval for the loan commitment until they have reviewed and approved the project design documents. Upon final approval, the mortgage lender and the borrower enter into a contract, and by the terms of that contract the project owner promises to construct the project according to the approved design, and the lender agrees to provide the funds for the stated period of time.

When a commitment for the long-term financing has been arranged, the construction loan is obtained. Commercial banks and savings-and-loan associations are common sources for such financing. To obtain this loan, the owner may be required to name its intended design firm and the contractor who will perform the work. Lending institutions typically limit their construction loans to no more than 75 to 80 percent of the estimated cost of construction. Thus, the owner is required to commit his equity in the amount of 20 to 25 percent of the contract amount. When the construction loan has been approved, the lender sets up a “draw” schedule that specifies the rate at which the lender will make payments to the contractor during the construction period. Typically, the short-term construction loan is paid off by the mortgage lender when the construction is completed. This repays the construction loan, and the mortgage is finalized, and the owner is left with the long-term obligation to the mortgage holder.

1.6.2 By Builder-Vendor

A builder-vendor is a business entity that designs, builds, and finances the construction of structures for sale to the general public. The most common example of this is tract housing, where the builder-vendor acquires land and builds housing units. This was referred to earlier as speculative residential construction, where the builder-vendors act as their own prime contractors, build dwelling units on their own accounts, and often employ sales forces to market their products. They intend to sell the residential property during the course of construction of the project or soon after the completion of the project. Hence, the ultimate owner incurs no financial obligation until the structure is finished and a decision to purchase the building is made.

In much of this type of construction, the builder-vendor constructs for an unknown owner. Many builder-vendors function more as construction brokers than construction contractors per se, often choosing to subcontract all or nearly all of the actual construction work. The usual construction contract between owner and prime contractor is not present in such cases because the builder-vendor occupies both roles. The source of business for the builder-vendor is entirely self-generated, as opposed to the professional contractor, who obtains its work in the open construction marketplace.

1.6.3 By Developer

A developer acquires financing for the owner's project in two different ways. A comparatively recent development in the construction of large buildings for business corporations and public agencies is the concept of design-finance. In this case, the owner teams up with a developer firm that provides the owner with a project design and a source of financing for the construction process. This procedure minimizes or eliminates altogether the initial capital investment of the owner. Developers are invited to submit proposals to the owner for the design and funding of a defined new structure. A contract is then negotiated with the developer of the owner's choice. After the detailed design is completed, a construction contractor is selected and the structure is erected.

The second procedure used by developers is currently being applied to the design and construction of a wide range of commercial structures. Here, the developer not only arranges project design and financing for the owner but is also responsible for the construction process. Upon completion of the project under either of the two procedures just discussed, the developer sells or leases the completed structure to the owner.

1.7 The Contract System

The owner of a proposed construction project has many different options available as to how the work is to be accomplished. It is true that public owners must conform to a variety of statutory and administrative requirements in this regard, but the construction process is a flexible one, offering the owner many choices as to procedure.

In the usual mode of accomplishing construction work, the prime contractor enters into a contract with the owner. The contract describes in detail the nature of the construction to be accomplished and the exact services that are to be performed. The contractor is obligated to perform the work in full accordance with the contract documents, and the owner is required to pay the contractor as agreed in the contract.

Experience has shown that owners can often reduce their construction costs by giving careful thought to the type of contract that best suits their requirements and objectives. The chances for a successful construction process are enhanced by thoughtful and thorough study by the owner before the process is initiated. The careful analysis and consideration of risk during the field construction is a critical issue. Typical contract choices force either the contractor or the owner to bear most of the risk. Each of these contract types has its advantages, but there are variations that apportion construction risks to the party that can best manage and control them.

The means by which the prime contractor is selected, the form of contract used, and the scope of duties thereby assumed by the contractor can be highly variable, depending on the preferences and requirements of the owner. Architects, engineers, and construction managers may provide consultation and assistance to the owner in this regard; however, it is the owner who will ultimately make the decisions. The prime contractor may be selected on the basis of competitive bidding, or the owner may negotiate a contract with a selected contractor, or perhaps a combination of the two may be used. The entire project may be included within a single contract, or separate prime contracts for specific portions of the work may be used. The contract may include project design as well as construction, or the contractor's responsibility may be primarily managerial. The owner may or may not utilize the services of a construction manager, and these services may vary in scope and description. It is to be emphasized here that the owner is the key participant here and is the person who will make these decisions.

1.8 Project Delivery Methods

1.8.1 Construction Services Only

A large percentage of construction contracts provide that the general contractor has responsibility to the owner only for the accomplishment of the field construction. Under such an arrangement, the contractor is completely removed from the design process and provides no input to the design. The contractor's obligation to the owner is limited to constructing the project in full accordance with the terms of the construction contract.

Where the contractor provides construction services only, the owner may have an in-house design capability. The more common arrangement, however, is for a private architect-engineer firm to perform the design by the terms of a contract with the owner. Under this latter arrangement, the design professional acts essentially as an independent contractor during the design phase and as an agent of the owner during construction operations. The architect-engineer acts as a professional intermediary between the owner and contractor and often represents the owner in matters of construction contract administration. Under such contractual arrangements, the owner, the architect-engineer, and the contractor play narrowly defined roles, each performing a particular function semi-independently of the others.

1.8.2 Design-Bid-Build

The design-bid-build project delivery method has for many years been the most commonplace method of project delivery for construction projects of all kinds. The process derives its name from the sequence in which the design and construction functions are performed. This project delivery method is also referred to as linear construction or as design-then-construct.

In the design-bid-build project delivery method, the process begins with the owner's perceiving a need for the construction of a facility. Typically, the owner considers financing and budget for satisfying the need he has recognized. The owner subsequently enters a contract with an architect or engineer, who will provide complete design services. The designer's basic responsibility as typically defined by the owner is the creation of an original design for a construction project that will satisfy the needs of the owner, within the owner's budget.

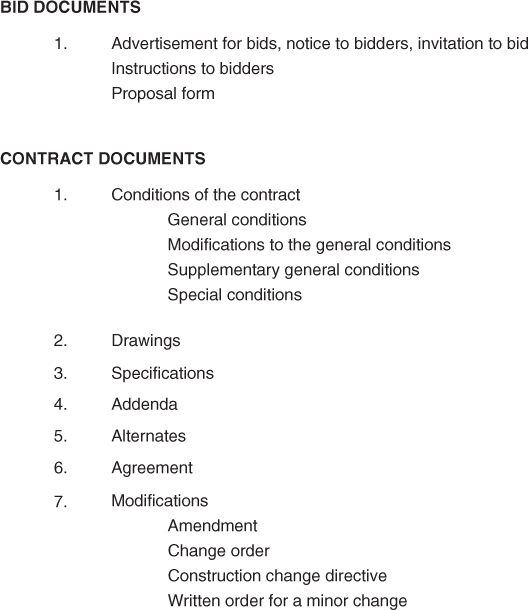

The owner's contract with the designer usually includes responsibility for production of a complete set of drawings and specifications that will communicate the design to the owner as well as to the contractor and will define the deliverables in the construction contract. Additionally, complete design services usually include the designer's authorship of all of the bid documents and contract documents for the project. The typical content of the set of bid documents and contract documents for a project is depicted in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Bid Documents and Contract Documents for a Construction Project

In addition to providing the services noted earlier, the architect-engineer who is the primary designer will typically provide contract administration services during construction, and representation of the owner's interests through observation of the work during construction, as well as closeout of the project and administration of any warranty issues after construction is complete. As previously noted, the exact nature of the services to be provided is set forth in the contract between the owner and the architect-engineer.

When all of the bid documents and contract documents have been produced and have been approved by the owner, the designer assists in announcing the project to construction contractors by means of an advertisement for bids, an invitation to bid, or a notice to bidders. Through these documents, contractors are made aware of the existence of the project, and are provided a brief description of the project and the form of contract to be employed. Additionally, the contractors are provided information with regard to how to obtain bid documents and contract documents, and are informed with regard to the date, time, and place where contractors' proposals are to be submitted.

The architect-engineer administers the process of making bid documents and contract documents available to the contractors. In addition, the designer will answer contractors' questions, and will provide interpretations and clarifications regarding the information in the contract and bid documents as requested, during the time when contractors are preparing their estimates, which is known as the bid period. Additionally, the architect-engineer will respond to written requests for information (RFIs) from the contractors during this period.

In addition, the designer will issue addenda as he deems necessary during the bidding period. An addendum (plural: addenda) is any modification to any provision of the contract documents or the bid documents for the project, issued by the designer during the bidding period. Addenda are issued in consecutively numbered sequence, and the designer will assure that he sends each new addendum to all of the contractors who have received bid documents and contract documents. Usually, when addenda are issued during the bidding period, the architect-engineer will require written and signed acknowledgment from each contractor on their proposal submitted on bid day that they have received and considered all of the addenda issued, identified by number.

The designer will usually administer the process of receiving the contractors' proposals on bid day, and will conduct the bid-opening process. The architect-engineer will then assist the owner with selection of the contract recipient and with execution of the agreement between the owner and the contractor.

After the contract has been signed between the owner and the contractor, the contractor will proceed to performance of the contract requirements. Throughout this time, the architect-engineer will provide contract administration services for the owner as defined in the owner-architect contract.

1.8.3 The Team Approach

An appreciable share of the private construction market is now utilizing the “team approach” for construction project delivery. This method of project delivery may also be referred to as integrated project delivery. When this method is followed, the private owner selects and enters agreements with the architect-engineer and the building contractor as soon as the project has been conceived. From this point forward, the three parties constitute a team that serves to achieve budgeting, cost control, time scheduling, and project design and construction in a cooperative manner.

Using the team approach, the owner assembles his key players, architect-engineer and contractor, to study the proposed project. The team determines the project program, and formulates project scope and budget, and the designer develops preliminary drawings from which the contractor makes conceptual cost estimates. As the process continues, the designer prepares the final drawings and specifications, and the contractor prepares more detailed estimates, and the owner makes the necessary financial arrangements. After financial commitments and required permits are obtained, the actual construction begins. During the course of construction of the project, the designer and contractor work closely together, modifying the design and drawings as may be required. The process offers the owner the advantages of time savings, cost control, and improved quality.

Where the team approach is used, the owner is mainly responsible for setting goals and parameters of the project, as well as providing the funding. The architect-engineer is responsible for developing the functional, aesthetic, and technical features of the building, and for preparing complete drawings and specifications in this regard. The contractor contributes its expertise in building materials, construction methods, construction costs, subcontractor coordination, and project scheduling.

1.8.4 Design-Build

The design-build method of project delivery has been rapidly gaining in popularity as well as in commonness of use in recent years. Most professional practitioners believe that this project delivery method will soon become the most prevalent method for delivery of design and construction services, certainly for buildings, and perhaps for other categories of construction as well. Some believe that the use of the design-build method has already surpassed the use of the design-bid-build method of project delivery for building construction.

The design-build method may also be referred to as the turnkey process or as the turnkey project delivery method. In the design-build system, the owner enters one contract with a single professional entity, and that firm has the responsibility for providing both design and construction services for the owner.

The design-build method of project delivery hearkens back to the days many years ago when there was a master builder who provided both design and construction services to the owner. Today, the design-build firm may be an architecture or engineering firm that is collaborating with, or has entered a partnership arrangement or a joint venture arrangement with, a contracting firm to provide design-build services. Or it may be a construction firm that has a collaboration agreement with a design firm, or a construction company that has in-house design capability. Additionally, some construction management firms (to be discussed in the next section) sometimes offer both design and construction capability.

The frequency of owners choosing to utilize the design-build method is explained by the fact that there are numerous benefits to be derived by the owner through his use of this method of project delivery. Perhaps the most important of these benefits is the inherent communication and collaboration that are central to this process, between those who will produce the design for the project and those who will perform the construction, from the inception of the project to final completion. The contractor's understanding of all aspects of the construction process, as well as his knowledge of construction materials and methods, and connections and details, in addition to his understanding of costs and his knowledge of estimating and scheduling, are important assets that he can bring to the project and that can be provided as input to the design process, beginning at the time the project is first conceived.

Additionally, when owners utilize the design-build method of project delivery, they derive the benefit of one firm's having singular responsibility to the owner for all aspects of both the design and construction. By contrast, in the design-bid-build system, designers usually produce the design, as well as authoring the bid documents and contract documents for the project, without any assistance or input from a contractor. Sometimes, after the construction contract is formed, there are miscommunications and misunderstandings and, at times, disputes between the designer and the constructor regarding various elements of the project design or with regard to a variety of different contract issues. This may lead to delays, additional costs, and perhaps claims. Additionally, when there is conflict, these occurrences leave the owner, who simultaneously has a contract with both the designer and the constructor, in the uncomfortable position of not knowing which of the professionals whose services he has engaged is correct. Owners who have endured such an experience are quick to say that the design-build method, with its single-point responsibility for all design and construction issues residing in one firm, can provide a significant benefit to the owner. Many owners are electing to utilize this design-build method of project delivery today, because of the numerous benefits that this method can provide for the owner.

1.8.5 Design-Manage

Design-manage is a term sometimes used to refer to a single-source construction service utilized by some owners. Design-manage is an arrangement where the owner enters into a single contract for both design and construction management services. In this arrangement, a single entity both designs the project and acts as a construction manager during the construction phase. A design-manage arrangement is often the result of a joint venture (see Chapter 2) between a design firm and a construction management enterprise.

With design-manage, the construction is typically performed by a number of independent contractors in contract with either the owner or with the design-manage firm, with the design manager planning, administering, and controlling the construction process. As is the case with design-construct and construction management, design-manage can, and usually is, utilized in fast-track construction. Fast-track construction is discussed further in another section of this chapter

1.8.6 Preengineered Buildings

Recent years have seen a large increase in the application of a specialized form of design-construct. Referred to as preengineered or systems building, this construction mode is now applied to a wide range of building types, from industrial applications to office buildings, retail centers, institutional buildings, and government-owned facilities.

Intended to provide an architecturally appealing building to meet an owner's specific requirements, this is a specialized design-build arrangement where the contractor is a dealer in metal structural systems and is directly affiliated with the manufacturer. The contractor, architect-engineer, and building manufacturer work closely together to create a finished project that serves the owner's needs in optimum fashion. Owners have found that preengineered metal buildings offer a competitive price along with a great deal of design flexibility. Such metal buildings now account for a significant share of the low-rise commercial and industrial construction market in this country. The Metal Building Manufacturer's Association (MBMA) is a national trade association of such producers.

Initially, preengineered buildings consisted of standard modules, but in today's market essentially every metal building system is custom engineered to meet the owner's specific requirements. The producer now has the ability to custom fabricate systems to fit specific project criteria. Manufacturers can fabricate complete metal buildings and multistory structural systems, including the framing, metal roof, walls, finishes, partitions, and necessary subsystems. These preengineered packages are presized, precut, and ready to be assembled on-site into a fully integrated building unit.

The component parts are shipped to the job site where the building is assembled and anchored to the foundation by a local contractor. These are metal building “builders” or “dealers” who are usually formally affiliated with the manufacturer and are usually full-service contractors assigned to serve a given geographical area. Many metal building contractors also market their product and services as subcontractors to other general contractors.

Metal buildings can be manufactured using many different exterior wall materials. A single manufacturer usually supplies a complete package of integrated building components that arrive at the job site ready for assembly and erection. Systems building of this kind has proven to have the advantages of speed of construction, design flexibility, high quality, economy, minimal maintenance, and relative ease of future expansion. Collectively, these features have led to a widespread acceptance of metal building systems by owners, as well as by other construction buyers and specifiers.

1.8.7 Fast-Track

Fast-track is a method of project delivery that is sometimes employed when the objective is to reduce to a minimum the time required for design and construction of a project. This method is also referred to as phased construction. Fast-track involves the assumption of considerable risk on the part of the owner, with the objective of reaping a return in dollars and/or time sufficient to justify the exposure or risk that is inherent in the method.

In fast-track construction, the design and construction functions for parts or phases of the project are “leapfrogged” with one another. Instead of awaiting the start of construction until a completed design for the entire project has been produced, fast-track applies a logic of designing one part or phase of the work and, as soon as that design is complete, awarding a construction contract and beginning construction on that phase.

While construction is under way on that part or phase, design proceeds on the next phase of the project, with the objective of having that design completed by the time construction is complete on the preceding phase or by the time the project is ready for construction on the second phase to begin. Then a construction contract is awarded for the most recently designed segment; at the same time, design proceeds on the next phase. This process continues until the project is complete.

For example, on a building construction project, with some basic information in hand, and with some assumptions made with regard to other aspects of the design of the building and the complete facility, site work and utility design can be completed and a construction contract awarded for this phase. While that work is under way, design of the foundation for the building commences. Again, some basic determinations will have been made regarding building size and footprint, structural loads, and so on, sufficient to allow a proper foundation design. As soon as that design is complete, and as soon as there will be no interference with site work and utilities operations that may still be under way, a foundation construction contract is awarded. While foundation construction is under way, design work continues for the building structural system. In this fashion, the design and construction functions are leapfrogged with one another throughout the project, until its completion.

The advantage of the fast-track method is that construction of the project can begin at the earliest possible time, and the construction of each phase of the building can begin without the need to wait for a complete design of the entire facility. This can significantly reduce the overall time required for design and construction.

The disadvantage, of course, is that when there is not a complete and integrated design for the project before construction commences, some retrofit may be necessary, and some work may have to be removed and replaced, or some parts of the project may be overdesigned because of the assumptions that needed to be made early, in order to allow construction to commence at the earliest time. The objective of fast-track is to have the overall time and dollar savings, which result from having the design and construction completed at the earliest possible time, be sufficient to compensate for the errors and the retrofit and “tear-out and redo” that may result from not having a complete and integrated set of design documents in hand prior to the onset of construction, so that in the end there is a net gain for the owner.

Design and construction contracts for fast-track construction can be structured in a number of different ways. Frequently, though not always, fast-track projects are accomplished by use of the design-build method, as discussed in a previous section. Fast-track is most commonly employed with the separate contracts system in use. Construction management services are also frequently utilized by the owner in the fast-track method of project delivery.

Critics of fast-tracking have argued that the process emphasizes time rather than quality. Additionally, the final construction cost is unknown at the start of fast-tracked construction, which is a form of contract referred to as an open-ended contract. Further, if bids for subsequent phases of the work come in over budget, redesign options to reduce cost are very limited. Fast-track projects sometimes take longer to complete than the usual, sequential process when applied to complex projects or if the fast-track process is not properly managed. As noted earlier, fast-track involves the assumption of considerable risk on the part of the owner. Despite these problems, however, fast-tracking has proven to be a successful and desirable owner option in some cases, when properly applied and managed. It remains a viable and sometimes useful project delivery method today.

1.8.8 General Conditions Construction

In the traditional construction process, general contractors customarily provide certain common job services for a project and for the contractors on-site, not only for their own forces but for their subcontractors as well. These services, called general conditions construction, or support construction, include many items normally required and described by the general conditions section of the project specifications. They involve such services as temporary electrical power, temporary heat, fencing and gates, parking areas for construction workers, access to the project, hoisting, weather protection, guardrails, stairways, fire protection, drinking water, sanitary facilities, job security, job sign, trash disposal, and so on. When separate contracts are used, the contractor who is designated as the general contractor or the coordinating prime contractor usually provides these general conditions services for the entire project, including work performed by the other prime contractors.

There are instances in which general conditions construction is the only part of the construction process actually performed by the general contractor. This would be true, for example, when the contractor, builder-vendor, or owner-builder subcontracts the entire project. Additionally, it should be noted that in some construction management arrangements, the construction manager provides support construction services.

1.8.9 Value Engineering

Value engineering is not as much a project delivery system as it is an accompaniment to many of the project delivery systems in use today. Value engineering may or may not be utilized on a project, at the discretion of the owner.

Conceptually, in value engineering the owner and the architect-engineer seek the input of the contractor with regard to his recommendations for alternative materials or systems, different from what the architect-engineer originally included in the design documents, which could be used on the project. The objective may be to reduce construction cost and/or to seek better value for the owner.

The circumstances in which value engineering is employed may vary considerably. Sometimes in competitive bid contracting, especially when the bids received from contractors exceed the owner's budget, the contractor who submitted the lowest proposal price will be asked to “value engineer” the project. This endeavor will be focused on the contractor's putting forth alternative materials or systems that he may recommend, which could be delivered at a lower cost than what was designed and specified in the contract documents prepared by the architect-engineer that the contractor utilized to prepare his original proposal. The architect-engineer and the owner will assess the contractor's recommendations and decide whether to accept or to reject any or all of the alternatives the contractor has put forth. For those accepted, the contract documents and the contract price will be modified accordingly.

At other times in competitive bid contracting, the contractor may be asked to submit his “value engineering” proposals as an accompaniment to his bid. These take the form of proposed alternates to the original contract documents, and again usually include the contractor's recommendations as to alternative materials or systems being proposed in lieu of what the original contract documents set forth, along with the change in price that would result from acceptance by the owner and architect.

In like fashion, sometimes in negotiated contracting and in the competitive sealed proposals method of contract formation (to be discussed later in this chapter), the contractor will submit value-engineering proposals for consideration. In each case, the contractor recommends alternative materials or systems that he believes could reduce the contract price and/or provide better value for the owner. If his recommendations are accepted by the architect and the owner, they are written into the contract agreement and are reflected in the contract price.

1.9 Types of Construction Contracts

A number of contract forms and types are available to owners for the performance of their construction projects. All call for defined services to be provided under contract to the owner. The scope and nature of such services can be made to include almost anything the owner wishes. The selection of the proper contract form appropriate to the situation is an important decision for the owner and is deserving of careful consideration and consultation. As has been noted previously, public owners must work within the strictures placed on them by applicable law. Some of the most commonly used types of construction contracts are discussed in the following sections.

1.9.1 Single-Contract System

In the single-contract system, there is one prime contractor who has a contract with the owner. This contractor is responsible to the owner for the construction of the entire project and for fulfilling all of the requirements set forth in the contract documents. The single-contract system is the most common type of contract system in use today. This contract system is illustrated in Figure 1.5 below.

Figure 1.5 Single-Contract System

In this contracting system, the distinctive function of the prime contractor is to coordinate and direct the activities of the various parties and agencies involved with the construction and to assume full, centralized responsibility to the owner for the delivery of the finished project as defined in the contract documents within the specified time defined as the project duration. Customarily, the prime contractor will construct certain portions of the project with its own forces and will subcontract the remainder of the work to various specialty contractors. The general contractor accepts complete accountability, not only to build the project according to the contract documents but also to ensure that all costs associated with the construction are paid.

The general contractor has privity of contract with the owner and is fully responsible for the performance of the subcontractors and other third parties to the construction contract. It is noteworthy that when a prime contractor sublets a portion of the work to an independent specialty contractor, the general contractor has a nondelegable duty to the owner for the proper performance of the entire work and remains responsible under his contract with the owner for any negligent or faulty performance, including that of the subcontractors. When the work is not done in accordance with the contract, the general contractor is in breach of contract and is liable for damages to the owner, regardless of whether the faulty work was performed by the contractor's own forces or by those of a subcontractor.

1.9.2 Separate-Contracts System

In the separate-contracts system, there is more than one prime contractor who has a contract with the owner. Each separate prime contractor is responsible for the performance of a scope of work as defined in his contract, but that scope of work includes only a specific and well-defined portion of the overall project. This separate-contracts system is illustrated in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6 Separate-Contracts System

When the separate-contracts system is employed, the owner will subdivide the project into well-defined segments, or phases, or elements of work and will define a work package for each of the various parts. This will in turn define the scope of work for each of the separate prime contracts. A separate prime contract will then be awarded for each of the work packages. Sometimes the owner performs the function of subdividing the overall work to be done and defining the various work packages and the contents of the several separate prime contracts himself, if he has the experience and the expertise necessary to do so. Alternately, the owner may rely on the expertise of the architect-engineer to define the work packages that comprise the separate contract and their scopes of work. At other times, the owner may utilize the services of a construction manager, in either a CMA or a CMAR capacity, to perform this function.