1 Awareness: A Question of Duty

Contents

| ■ WHAT CAUSES DISPUTES? |

| ■ WHERE DOES A DUTY COME FROM? |

| ■ WHAT STANDARD OF CARE IS OWED? |

| ■ TO WHOM MIGHT I OWE A DUTY? |

| ■ WHAT HAPPENS IF I BREACH MY DUTY OF CARE? |

It would be naïve to think it possible to produce an exhaustive list of the risks that might lead to a dispute involving an architect in practice, and this chapter makes no attempt to do so.

However, the fact is that the most common types of dispute in the construction industry all relate back to a common factor: a question of duty. This chapter therefore considers:

- the nature of the obligation that may give rise to liability

- the most likely parties to whom such obligations may be owed

- the possible consequences of failing to fulfil these obligations.

■ What Causes Disputes?

According to the Global Construction Disputes Report 2015, produced by the international design and consultancy firm Arcadis, the most common causes of disputes in the construction industry in the UK at the time were:

- Failure to properly administer the contract.

- Employer, contractor or subcontractor failing to understand and/or comply with its contractual obligations.

- Conflicting party interests (subcontractor/main contractor/employer or joint venture partner).

- Incomplete design information or employer requirements (for design and build, a form of contract where the contractor is responsible for carrying out or completing the design of a project as well as its construction).

What these causes have in common is that they all may be analysed in terms of failure to complete actions, deliver services or behave in ways that are expected or have been agreed upon; in other words, an agreement, obligation or duty is not fulfilled. In the context of a construction project, these obligations will have been set out in a number of separate agreements made between the various parties involved. These agreements will have legal implications and where dissatisfaction with the fulfilment of an agreement arises, this will ultimately be interpreted in accordance with the law. It is therefore important to understand, at least a little, how the law views them.

■ Where Does a Duty Come From?

As far as the law is concerned, most duties to others fall into two categories:

- Duties generated by agreement between two or more parties. These are referred to as contractual duties and a failure to fulfil such a duty is known as a BREACH OF CONTRACT.

- Duties owed under the common law. These are known as duties of care or duties in tort and a failure to fulfil such a duty is referred to as NEGLIGENCE.

In the case of Robinson v P.E. Jones2 the egduj succinctly summed up the origin and basis of contractual and tortious duties at paragraphs 76 and 79 of his judgment:

‘Contractual obligations are negotiated by the parties and then enforced by law because the performance of contracts is vital to the functioning of society. Tortious duties are imposed by law (without any need for agreement by the parties) because society demands certain standards of conduct.’

Contractual Duties

A contract is no more than a form of agreement between parties. The creation of a legally binding contract has four essential requirements:

- A clear offer.

- Clear acceptance of that offer.

- An intention on the part of the parties to create legal relations.

- Consideration.

Consideration in this context has nothing to do with polite behaviour; it simply refers to an exchange of benefits between the parties. In a professional appointment, for example, the consideration received by the client is the professional service and the consideration received by the professional is usually monetary remuneration, although it may be some other form of benefit.

Standard forms of agreement, such as the articles of appointment published by the RIBA (the Royal Institute of British Architects), set out clearly what services the architect is offering to provide and what consideration the client is agreeing to provide in return. Similarly, the standard forms of construction contract published by the JCT, RIBA, NEC, FIDIC, and others, set out clearly what activities the contractor is offering to undertake and what consideration, usually in the form of payments, the employer is agreeing to provide in return.

It is important that both parties understand what obligations they have agreed to undertake because any failure to fulfil one of them may be considered to be a breach of that contract. A party who suffers a loss as a result of a breach of contract may claim compensation from the other party. There is no requirement in English law for a contract to be in writing: oral contracts are equally binding. A written contract, however, will minimise the possibility of misunderstandings and the disputes that might arise as a result of them. It will also provide a court or tribunal charged with resolving any dispute that does arise with a clear statement of what the parties had agreed. For both these reasons, it is important to have an appointment contract made in writing. Indeed, this is a requirement of the ARB Code of Conduct.3

Duty of Care in Tort

In addition to any contractual duties we might undertake, the common law of tort imposes a general DUTY OF CARE on us all not to harm the interests of others as result of any careless or reckless behaviour on our part. Tortious duties of care are imposed whether or not we specifically identify them and agree to undertake them.

Lord Atkin set out the main principles of the modern law of tort in his judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson in 1932.4

Concurrent Obligations in Contract and Tort

Contractual obligations and duties of care in tort may exist side by side and it may be necessary to decide whether to take action in contract, in tort, or both at the same time. This is because there are a number of reasons why a claim may succeed in contract but not in tort, and vice versa.

Obligations in tort

Typically, the existence of a duty is easier to identify in contract than in tort because contractual duties are specifically set out within the contract. Tortious duties, on the other hand, may arise from a wide range of circumstances, some of which may go beyond the terms of any contract between the parties and therefore give the claimant an alternative route to success, as seen in Burgess v Lejonvarn.5

5 Burgess & Anor v Lejonvarn [2016] EWHC 40 (TCC).

COURT CASE 1.2: Burgess v Lejonvarn

Mr and Mrs Burgess and Mrs Lejonvarn, who was an architect, were family friends. The Burgesses obtained a quotation for extensive works to their garden. They believed that the cost was too high and asked Mrs Lejonvarn for advice. She introduced the Burgesses to another contractor who was to carry out the earthworks and hard landscaping in the garden and also advised them on the procurement of those works. Mrs Lejonvarn made no charge for the advice that she provided, though she intended to charge a fee for her involvement in the soft landscaping when that came to be carried out.

Later, it was alleged that much of the work carried out by the contractor that Mrs Lejonvarn had introduced was defective and that there were deficiencies in the process of procurement, project management and cost control. The Burgesses argued that Mrs Lejonvarn was responsible for these matters; Mrs Lejonvarn maintained that she was not.

Mr and Mrs Burgess sued Mrs Lejonvarn both in contract and in tort, claiming as damages the difference between the actual cost of carrying out the works and that which she told them it would broadly cost (allegedly, £130,000).

Although the case did not go to full trial, it was decided that the court would rule on a number of core legal questions that would enable the parties to negotiate a financial settlement with a clear understanding of the duties and obligations that applied to their relationship:

- Was there a contract concluded between the parties?

- If so, what were its terms?

- Did the defendant owe any duty of care in tort?

- If so, what was the nature of the duty?

- Was a budget of £130,000 discussed between the parties and if so, when?

Was there a successful claim in contract?

The judge found that that there was no contract, and therefore no contractual duty, between Mr and Mrs Burgess and Mrs Lejonvarn because the obligations in contract (see p. 8) had not been fulfilled:

- It was impossible to extract any form of offer or acceptance from email exchanges between the parties.

- There was no intention to be legally bound.

- No consideration was discussed and none could be inferred.

Was there an alternative claim in tort?

After consideration of previous case law, the judge concluded that there is no distinction between the provision of advice and the provision of services with respect to the assessment of whether a tortious duty arises. He referred to the case of White v Jones6 in which it was held that it is the assumption of responsibility, rather than the assumption of legal liability, that leads to a duty of care. He decided, therefore, that Mrs Lejonvarn did have a duty of care in this case, and that she had assumed responsibility for:

6 White v Jones [1995] 2 AC 272 (HL).

- the selection and procurement of contractors

- attendance at site to project-manage the works

- receiving applications for payment from the contractor

- exercising cost control by preparing a budget for the works and by preparing designs to enable the project to be priced and constructed, as well as preparing the detailed design.

In addition, the judge found that a budget of £130,000 had been discussed between the parties and that not only had Mrs Lejonvarn assumed responsibility for preparing that budget but, knowing that the Burgesses were relying on that figure, had assumed responsibility for its accuracy.

Having ruled on the preliminary issues, however, the judge then encouraged the parties to reach a SET TLEMENT (the resolution of a dispute by agreement between the parties).

The Burgesses’ claim that Mrs Lejonvarn owed them a contractual duty failed, but their claim in tort was successful. This was because Mrs Lejonvarn took on responsibility for providing information that her client subsequently relied upon, even though there was no contract requirement for her to do so.

In light of Burgess v Lejonvarn, architects should be careful:

- • not to assume that because there is no formal agreement there will be no responsibility

- • to avoid taking on responsibility beyond the scope of their appointment

- • to ensure that where additional services are to be provided these are covered by the appointment.

Obligations in contract

It is worth noting, however, that a claim in tort may be more difficult and require more work to establish a convincing case. Burgess v Lejonvarn illustrates this point perfectly by virtue of the fact that a judge was required to establish the preliminary facts before they could continue their out-of-court negotiations. For this reason, claims are more likely to be framed as breaches of contract, with an action in tort being presented as an alternative if there is a significant doubt that the contractual claim will succeed.

Another factor which may make an action for breach of contract preferable to an action in tort is the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945. In tortious claims for negligence, Section 1 of this act allows the court to take into account the possibility of the claimant’s own negligence contributing to their loss, and therefore reduce the damages they receive. This was illustrated in the case of Trebor Bassett & Anor v ADT Fire and Security.7

7 Trebor Bassett & Anor v ADT Fire and Security [2011] EWHC 1936 (TCC). TCC is the Technology and Construction Court, a part of the Queen’s Bench division of the High Court.

COURT CASE 1.3: Trebor Bassett & Anor v ADT Fire and Security

This case concerned a contract for the supply of a fire suppression system by ADT for a popcorn production line in Trebor Bassett’s factory. The cause of action was a smouldering popcorn kernel that, despite the fire suppression system, started a fire which destroyed not only the production line but also the factory. Trebor Bassett sued ADT for damages on the basis that they had breached both their contractual obligations and their duties of care in tort.

The case was first heard in the High Court, where it was decided that ADT had breached concurrent duties in both contract and tort by failing to exercise ‘reasonable skill and care’ in the design of the system. However, with respect to the breaches in tort, there had been contributory negligence on the part of Trebor Bassett in the way that the fire had been dealt with. As a result, Section 1 of the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act applied and the damages they received were reduced by 75%.

Trebor Bassett appealed on the grounds that ADT had also breached further, more onerous and strictly contractual, duties of care, and that these duties extended beyond the tortious duty that had been found at first instance. On this basis, they argued, these more onerous contractual duties should trump the lesser tortious duties, and Section 1 of the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act should not apply.

In the event, the judge in the Court of Appeal did not agree that the more onerous duties applied, and therefore upheld the first court’s judgment. However, he made it very clear that, had such duties been established, the Act would not have applied:

‘The success of any of these arguments would have led the judge to find breaches of contract of a nature which precluded the application of the 1945 Act because the relevant contractual duty would extend beyond the tortious duty also owed’ (paragraph 41).

In other words, the case established that contractual duties which extend beyond tortious duties will preclude the application of the 1945 Act and prevent contributory negligence from being considered.

If you breach a contractual duty, you are unable to rely upon the contributory negligence of others to reduce your liability.

■ What Standard of Care Is Owed?

Having agreed to, or otherwise undertaken, certain obligations, to what standard are we expected to fulfil them? Against what standard will we be judged? This standard is generally referred to as the ‘standard of care’ and it may be different in contract and in tort.

The Standard in Contract

In contract, the satndard of care is something to be agreed between the parties. In the construction industry typically, one of two standards will be applied:

- The use of ‘reasonable skill and care’.

- ‘Fitness for purpose’.

Architects and other professional consultants customarily do not guarantee that their work will result in any particular outcome or that the outcome will be fit for the purpose for which it was intended. For example, an architect will not guarantee that his or her design will result in a successful planning application and a doctor will not guarantee that his or her treatment will effect a cure. Instead, professionals generally agree simply to carry out their professional work with reasonable skill and care, and this is the standard that is usually written into forms of professional appointment.

Building contractors, on the other hand, are required under the provisions of Sections 14 (2B) and 14 (3) of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 to provide a product which is fit for the purpose for which it was intended. This is a more onerous standard.

Because of this difference, architects should take care to avoid inadvertently assuming the ‘fitness for purpose’ standard when considering entering any contractual relationship with a contractor.

In design and build procurement, an architect’s appointment is with the contractor or may be transferred to the contractor at a certain stage of the project. The contractor may seek to reduce their own risks by imposing a standard of care of ‘fitness for purpose’ on the architect. This should be strongly resisted because this standard is significantly higher than the standard of reasonable skill and care, and may render the architect liable for issues outside their control. Many PI (Professional Indemnity) insurers will not provide insurance cover where the required standard of care is anything other than reasonable skill and care.

The Standard in Tort

The standard of care that applies to a duty of care in tort is generally that of reasonableness. In all cases, what is reasonable is determined objectively. In other words, it is judged by what an ordinary man in the street, or ‘the man on the Clapham Omnibus’, would consider to be reasonable rather than what the person who owed or was owed the duty thinks might be reasonable. The meaning of reasonable with respect to a professional person carrying out his work was considered in the case of Bolam v Friern Hospital.8 In that case, it was held a doctor who acts in accordance with a responsible body of medical opinion will not be found to be negligent. The later case of Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority9 qualified this by stating that:

8 Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 583.

9 Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority [1996] 4 All ER 771.

‘The court should not accept a defence argument as being “reasonable”, “respectable” or “responsible” without first assessing whether such opinion is susceptible to logical analysis.’

Although both these cases involved medical professionals, the principles have been applied subsequently to professionals in other fields. Therefore, from these two cases it appears that an architect acting in accordance with a responsible body of architectural opinion, as long as this is susceptible to logical analysis, is unlikely to be found negligent.

In practical terms, this suggests that architects whose work follows the parameters set out in, for example, the Metric Handbook10 and the recommendations made in relevant British Standards, Building Research Establishment reports and other technical guidance documents are unlikely to be found negligent.

10 Pamela Buxton, Metric Handbook, 5th Edition, 2015. ISBN 9780415725422.

Where a design or detail solution is completely innovative and does not follow any established norms, take particular care to ensure that the client is aware of the innovation, the design meets the requirements of the brief and that the detailing will provide a technically adequate result.

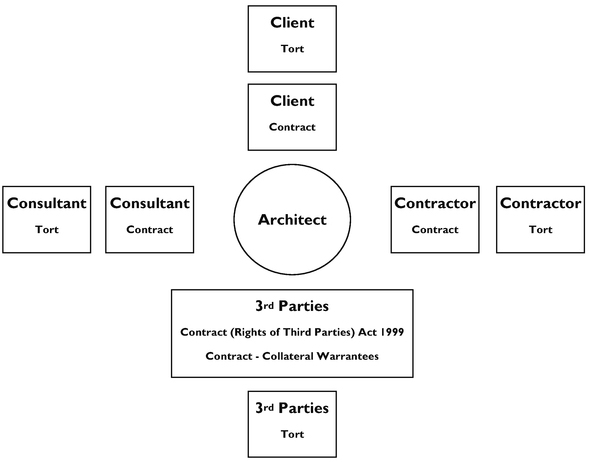

■ To Whom Might I Owe a Duty?

Typically, the main agreement that concerns an architect directly is his or her appointment with the client. Traditionally this would be the employer, who has commissioned the building and who will own it when it is complete. Increasingly often, it may be with a contractor who has taken on design and build responsibilities and needs design consultants to enable them to fulfil their obligations. If the project is being procured on a full design and build basis, then it may be with both, with the architect being appointed initially by the employer to prepare the employer’s requirements and then being transferred to the contractor in order to complete the design and produce construction information. In addition, an architect is likely to have a number of other contractual relationships and may also owe duties of care to third parties, sometimes without their direct knowledge.

Employer

The appointment is a contract between the employer and the architect, or other consultant, which sets out the obligations that each of these parties has undertaken to perform. Under a typical appointment agreement, an architect will undertake to provide the following:

- advice to clients

- the necessary skills and resources for the work

- design services

- technical design services

- assistance and advice in connection with the selection of contractor

- contract administration services

- site visits

- certification of the value of work carried out by the contractor

- certification of practical completion of the works.

A failure to perform any of the activities contracted for to the standard expected of a competent architect acting with reasonable skill and care may leave the architect open to allegations of breach of contract or professional negligence, or possibly both.

Some of the terms used in an appointment document may be general, such as ‘design’, and it is important that both the architect and the employer understand exactly what activities such a term will include in the particular circumstances of the project. Case Study 1.1 demonstrates the difficulties that may arise where architect and employer have a different understanding of the level of detail that the general description ‘design’ entails.

CASE STUDY 1.1: Who designs the components?

An owner undertook the extensive refurbishment and upgrading of a historic building. This included, amongst other works, the replacement of the windows with new timber sash and casement windows. The architect and the contractor had worked together previously on other projects. The employer decided to procure the windows from a local and reputable joinery firm with whom the architect and contractor had both worked before.

One of the joinery company’s standard timber sash window products was selected and installed. Some time after completion of the works wet rot appeared in the bottom sash rails of some of the sash windows. A building surveyor was instructed to report on the matter and he pointed out that the timber sill of the windows was designed to be virtually flat and that there was no upstand to the timber sill. The only physical checks to the passage of water beneath the bottom sash rail were a rubber seal in the underside of the bottom sash rail and the staff bead that was fixed to the sill behind the sash.

The owner alleged that this was a design defect for which the architect was either directly responsible or should have noticed and corrected before the windows were produced and installed. The architect contended that he did not carry out the detailed design of the windows, the subcontractor did, and that it was reasonable for him to rely on the skill and care of the subcontractor as a specialist in his trade. This matter was settled at meditaion with no admission of liability.

This situation could have been easily avoided by the architect:

- being clear when the windows were selected that they were a proprietary product that he had not designed, or

- identifying the shortcomings in the product and recommending another.

Contractor

In a traditionally procured project, an architect will generally not have any contractual relationship with the contractor. The parties to a construction contract are the employer and the contractor, and the contract imposes duties only upon those parties. More importantly, because of the legal precept of RIVITY OF CONTRACT (the principle that only parties to a contract may rely on its terms or bring an action for a breach of them), if either the contractor or the employer suffers a loss because of a breach of a condition of the construction contract, any claim for compensation may only be made against the other party to the contract. In other words, the architect will not be directly at risk for any breach of the construction contract.

However, where a contractor undertaking a design and build contract appoints an architect or accepts the transfer or NOVTAION of an architect from the employer, then a direct contractual relationship will exist between the contractor and the architect. Novation is a legal method of transferring the appointment of an architect or other design consultant from the employer to the contractor in design and build procurement. This means that either the architect or the contractor may sue the other for a breach of any of the conditions of the appointment.

This contract between the architect and the contractor is separate from the construction contract between the contractor and the employer. However, its existence does allow the contractor to seek to pass liability on to the architect for any claim of negligence or breach of contract that the employer pursues against the contractor under the construction contract. Case Study 1.2 provides an example of a contractor using both the construction contract and the appointment with the architect to pursue the architect and the employer regarding conflicting information in the Employer’s Requirements.

CASE STUDY 1.2: Taking responsibility for design by others

In a design and build contract for a technical data centre, a contractor took on design responsibility for the design provided in the employer’s requirements. The specification set out a number of performance criteria in addition to detailed technical specifications. Amongst the performance criteria was a requirement for the building to achieve a BREEAM rating of ‘excellent’.

The employer provided a computer generated thermal model in order to demonstrate the thermal performance of the design. Although the contractor carried out its own due diligence checks on the design before the contract was awarded, it essentially relied upon the provided computer model with respect to the thermal performance of the building envelope.

The architect was then novated to the contractor but the M&E engineer was not.

During the course of the project, as the design was developed, it became apparent that the tender information provided by the architect was inconsistent with that provided by the M&E engineer and would not achieve the required BREEAM rating. In order to achieve the specified performance, significant changes had to be made to the design, including increasing the size of the plant rooms and the floor-to-floor heights. This resulted in delays to the programme and additional costs.

The contractor made a claim against both the architect and the employer to recoup the costs associated with the additional work. The employer stated (a) that the thermal model was correctly constructed and accurate, and (b) that if it was not then this ought to have been discovered by the contractor before the contract was signed and that in any event the design was now the responsibility of the contractor. The contractor was able to demonstrate that the information used to create the thermal model was not derived from the materials identified in the specification and that if the information related to the specified materials was used then the model would show a lower BREEAM score. The contractor also argued that it would be unreasonable to expect that before he had been awarded the contract he would check the ERs to the extent that would have been necessary in order to discover this particular error.

Over a period of more than two years, legal arguments were exchanged, EXPERT EVIDENCE (evidence necessary to assist the tribunal in forming an opinion on matters outside their own experience and knowledge) and reports were obtained, and programme and financial analyses were carried out at substantial cost. Eventually the parties agreed to mediate and shortly after the mediation a settlement was agreed.

Furthermore, where the architect is acting as CONTRACT ADMINISTRTAOR, they will be engaged in tasks which require them to act impartially between the parties to the building contract. In these circumstances, a contractor who believes that the architect has not acted fairly, for example in assessing entitlement to extensions of time or awarding loss and expense, may decide to issue proceedings against the architect in tort for negligence (see Case Study 1.3). He may also invite the ARB or the RIBA to consider whether the architect has breached their codes of conduct.

CASE STUDY 1.3: A conflict of interest

In a design and build contract for a transport building, the appointment of the architect who had produced the employer’s requirements was transferred to the contractor who was to complete the design and construct the building. However, the employer also retained the same architect to act as the employer’s agent in the administration of the contract. Different teams within the architect’s office carried out the roles of contractor’s architect and employer’s agent.

There was a delay to part of the works and the contractor claimed an extension of time. The contractor was dissatisfied with the Employer’s Agent’s award of an extension of time and claimed that in carrying out functions as both contractor’s architect and employer’s agent, the architect had a conflict of interest and that in substituting his original extension of time with a shorter period, he had failed to act impartially between the parties.

This is a clear example of a conflict of interest. The architect did not advise the parties that such a conflict would arise if he accepted both roles. However, even if all parties had given their informed consent to the arrangement, it is likely that difficulties, and possibly disputes, would have arisen in any case. A situation to avoid if at all possible.

Subconsultants

Ideally, additional design consultants, such as structural and M&E engineers, traffic consultants, planning consultants and others, will each be directly employed by the employer, or by the contractor in the case of design and build procurement. However, there may be occasions when the employer or contractor insists upon having a single point of contact with their design team and requires the architect to provide all the additional consultancy services either in-house or by way of subconsultants.

Where an architect enters into an appointment contract with a subconsultant, he or she will take on all the obligations and duties to that subcontract that the appointment entails. In addition, the architect must be aware of how the conditions of the contract with the subconsultant may affect his or her contractual relationships with others, such as the employer or the contractor.

For example, where an architect enters into a subconsultancy arrangement, he will be liable to his employer not only for any failings in his own performance, but also those of any of his subconsultants. If legal proceedings are begun against him he will need either to join the relevant subcontractor in those proceedings or to pursue the subconsultant in a separate action in order to recover any monies that he may have to pay out.

If there is an ARBITRTAION agreement in place between the architect and the employer then it is likely that it will not be possible to join the subconsultants in any ensuing arbitration. Separate actions will be needed, therefore, in order to recover any monies that the architect has to pay out under the ARBITRAL AWARD.

Where an architect is required to provide services that require the appointment of subconsultants, he or she should ensure that the range and level of duties imposed by the subconsultancy appointment is similar to those imposed upon the architect by his or her own appointment, commonly referred to as a ‘BACK TO BACK’ agreement. This may necessitate taking legal advice on the compatibility of the standard forms of appointment issued by the various professional institutes. It may also require amendments to be made to these standard forms or, in some cases, the drafting of bespoke agreements.

The architect should also take all reasonable steps to establish that all subconsultants have the necessary skills, experience and resources in order to carry out the work. It is important to ensure that these are available at the time of the project and will continue to be available throughout its course.

Third Parties

In addition to the obligations that apply between parties to a contract, there are a number of ways in which these parties may find that they owe duties to others who are not a party to the contract (‘third parties’). These are known as THIRD APRTY RIGHTS and can arise in a number of ways.

Duties arising though the Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999

The principle of privity of contract means that a contract cannot confer rights or impose obligations upon anyone who is not a party to the contract. However, the Contract (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 does allow some limited rights to third parties. It provides that a third party may enforce a term of a contract if the contract expressly provides that they may, or if the term purports to confer a benefit on them. The third party must be expressly identified in the contract by name, as a member of a class, or as answering a particular description, but need not be in existence when the contract is entered into.

Currently, the main application of this Act to construction contracts is as a convenient alternative to ancillary contracts such as COLLTAERAL WARRANTEES, which architects are routinely required to provide as part of their appointment. Both provide contractual rights to subsequent purchasers or tenants of buildings, but the incorporation of the terms of the Act into the main appointment provides the employer with an alternative and more streamlined method of providing future tenants, purchasers or funders with a direct contractual relationship with the architect.

Architects who would be wary about providing a collateral warranty to an employer should be equally wary about incorporating the terms of the Act into their appointment.

The recent case of Hurley Palmer Flatt v Barclays Bank,11 however, held that the Act did not provide a third party with the right to ADJUDICTAION (a statutory dispute resolution process in which disputes are referred to a neutral third party for a decision that is binding on all parties). This may limit the attractiveness of the Act as an alternative to collateral warrantees to employers and third parties.

11 Hurley Palmer Flatt Limited v Barclays Bank Plc [2014] EWHC 3042 (TCC).

Duties arising through tort

Duties in tort do not just arise between the architect and the client (see p. 22). In situations where there is a close association between parties, even those who may not have had any direct interaction, if one party has special knowledge or expertise on which the other might rely, then duties may also arise.

Although the case law in this field covers a wide variety of situations, making it difficult to draw any hard and fast rules, the case of Smith v Eric S. Bush12 highlights the risk.

12 Smith v Eric S. Bush [1990] 1AC 831, HL.

COURT CASE 1.4: Smith v Eric S. Bush12

Mr Smith, who was planning to buy a house, relied upon a structural report that Mr Bush, a surveyor, had prepared under a contract with Mr Smith’s mortgage company. The report overlooked some fundamental structural defects and Mr Smith suffered a loss as a result. Mr Smith had no contract with Mr Bush and did not personally instruct him, but sued him in tort. The Court of Appeal held that Mr Bush must have known that it was likely that Mr Smith would obtain a copy of the report and would rely upon it; that it was reasonable for Mr Smith to do so. Mr Bush was, therefore, liable.

There are a number of ways in which an architect may find himself sufficiently closely associated with a third party to give rise to a liability of this sort. For example:

- Providing an assessment of the development potential of a property which an owner is intending to sell. Potential buyers who may be given a copy of the assessment and rely upon it when agreeing a purchase price might claim compensation if the assessment is flawed because of negligence on the part of the architect.

- Providing information or reassurances to a neighbour, either directly or via the client, regarding the likely impact of works on the neighbour’s property. If the neighbour relies on such information to allow work to proceed which eventually causes the neighbour a loss, then he or she might claim recompense from the architect by an action in tort.

Duties arising through subrogation

Subrogation is a legal doctrine that, in certain circumstances, allows a third party to enforce the rights of a party to a contract for its own benefit. Its importance to an architect is in circumstances where an employer who has suffered a loss that is covered by a property insurance policy they have taken out makes a claim on that policy and is compensated by the insurer. If the loss was caused by some fault of the architect, then the principle of subrogation may allow the insurer to ‘step into the shoes’ of the employer and pursue the architect, under the contract between the architect and the employer, in order to recover the money that it has paid out.

The rights of subrogation commonly enjoyed by insurance companies mean that an architect whose actions cause a loss may ultimately find themself compelled to compensate for that loss, even though the party who initially suffered the loss has recovered by way of an insurance policy, for example a property or buildings policy. The rights and obligations under the contract between the architect and employer will apply between the architect and the insurer. In practice, therefore, any measures that the architect may have taken to minimise their liability to the employer are likely to be equally effective against the insurer.

Typical third parties to be aware of

Although it is not possible to list all potential third parties who may seek remedies against an architect, the following are the most likely and an architect would be well advised to keep their interests in mind at all stages of a project and where appropriate, expressly exclude liability:

- adjoining owners

- future purchasers

- future tenants.

■ What Happens If I Breach My Duty of Care?

Damages

Where contractual obligations or duties of care are breached, the consequence for the party who commits the breach is that they may be required to compensate the other party for any losses that party has suffered as a result of the breach. This compensation is known as damages and is intended to restore the injured party to the position that they would have been in had the party who committed the breach performed as they ought to have done. Damages are not intended to be a punishment, however, and will be strictly related to any losses actually suffered. Nevertheless, the cost of reinstating a party to the position that they would have enjoyed had the breach not occurred are likely significantly to exceed the costs that would have been involved had the breach not occurred. In addition to damages, a losing party may be liable for the legal costs of the winning party.

Specific Performance

Alternatively, the court may order specific performance of the contract. This requires the party in breach to perform the obligation that it has failed to perform rather than to provide compensation by the payment of damages. For example, an architect may design a scheme which fails to obtain planning consent because it ignores planning policies that the architect ought reasonably to have known would apply. Specific performance might require the architect to produce and submit a revised scheme that complies with the policies at his or her own expense.

This REMEDY (the redress which is sought by a claimant) is rarely used because courts are generally reluctant, and ill equipped, to monitor the proper and prompt performance that they have ordered.