Figure 10.1 The funeral of one of the 11 people killed in the Remembrance Day bombing in Enniskillen, Sunday, November 8, 1987. The procession is shown passing the bombing scene in the background. Photographed by Raymond Humphreys, Impartial Reporter, Enniskillen, Northern Ireland. (Used by permission of the photographer.)

The Threat to Belonging in Enniskillen: Reflections on the Remembrance Day Bombing

On Sunday morning, November 8, 1987, a bomb exploded in a building adjacent to the War Memorial in the market town of Enniskillen, Northern Ireland. Eleven people were killed and over 60 were injured, some very seriously. Over 400 people, it is estimated, who had gathered for the annual Remembrance ceremony were in close proximity to the explosion. Apart from the terrible consequences for those directly affected, the bombing and its aftermath was one of the most dangerous episodes in the recent political strife in Northern Ireland and threatened to lead to a cycle of greater violence. Locally, it threatened to undermine the well-being of the total community as the attack was perceived to be a sectarian attack on the Protestant and Unionist community, leading in turn to fears of reprisals within the Catholic and Nationalist community.

The building in which the bomb had been placed was immediately adjacent to the footpath on which bystanders stood every year to watch and participate in the ceremony. The building collapsed, sending up a huge cloud of dust and debris, and falling down on top of those who were standing around. Many people were trapped under the wall of the building as it fell, pinned against the railings, which protected pedestrians from the road. The time was just about 10:40 a.m. The parade of the Ballyreagh Silver Band and the service and exservice personnel had not yet departed from its assembly location at the College of Further Education, about 200 yards away. At the sound of the explosion, many ran towards the scene, fearful for friends and relatives. Others ran away in terror. The accounts of people’s experiences in these moments are chilling and deeply moving: the man who wandered around looking for his mother, whom he found out some hours later had been killed; the woman who ran towards the scene in terror and concern for her mother, whom, unknowingly, she had passed on the way as her mother fled from the scene. She then searched through the debris and the dying for her mother and now lives with powerful and unforgettable memories of that dreadful day. One young man, standing between his parents, survived with relatively minor injuries, while both his parents were killed.

Many came to the rescue, and a process of removing the dead and injured began—a scene captured on video by an amateur cameraman and shown around the world on news bulletins. Within a few hours after collating the information from the scene, the temporary mortuary, and the nearby Erne Hospital, the extent of the tragedy was established. Most of the injured were brought to the Erne Hospital, about half of a mile away. As it was a Sunday, the outpatients and operating theatres were all but empty, leaving them free, along with the radiography, laboratory, and CSSD (Central Sterile Service Departments) departments, to spring into action. Hospital staff were called in or came to the hospital of their own initiative on hearing of the explosion.

The present writer was at church less than half a mile away when the bomb exploded. A short time later, I went to the hospital and was met with a scene of utter mayhem. What struck me was the powerful sense of unreality in seeing the familiar hospital environment filled with so many disheveled and distressed people. People were arriving all the time and, within minutes, the accident and emergency department was inundated.

Together with another social worker, I was at the hospital for a number of hours until after the situation returned to some degree of order. The primary task involved linking people with others or facilitating contact between families, their injured relatives, and medical or nursing staff. Also, I and other staff responded to inquiries from the media, which were seeking regular updates for newsflashes and regular bulletins. It was a fast-moving few hours, with very distressed people seeking information about lost relatives, a high level of uncertainty about who was where and how many had been killed, and helicopters landing outside the front door of the hospital to take seriously injured to regional hospitals. A few hours later, it all seemed strangely quiet.

A History of Conflict

Before exploring the implications for the community of the bombing, some background to the conflict in Northern Ireland will place what is to follow in context. At the time of this chapter’s writing, the constitutional position of Northern Ireland is in dispute. Six out of the 32 counties that make up the whole island of Ireland continued to be governed from Britain after the political settlement between the British Government and the Irish Nationalists in 1921. The other 26 counties then formed the new Irish Free State. In the years that followed, nationalists have aspired to a united Ireland, independent from Britain. With matching vigor, the unionists (those supporting union between Britain and Northern Ireland) have sought to retain the constitutional link.

At times in the years since the 1920s, the aspiration of nationalists has been expressed in violence, particularly by extreme nationalists who pursue a republican ideal for Ireland. This violence has at times been directed at institutions and interests closely associated with Britain, including attacks on economic, constitutional, and security targets. On other occasions, it has been directed at the unionist population.

Two other points are important to note. First, the violence of republicans has been matched by the violence of extreme unionists (often referred to as loyalists, viz. loyal to the British crown). Second, an understanding of the various interests in the constitutional conflict is bedeviled by the use of various terms, which are often used interchangeably but actually have precise meanings. To simplify, the Roman Catholic community is, generally speaking, nationalist in its political aspirations and identity, and republicans (extreme nationalists) are generally taken to be from the Catholic community. Conversely, the Protestant community is, again generally speaking, unionist in its aspirations and identity. Loyalist is a term used to identify those with pronounced unionist views and is usually applied to those who use or support violence to defend the link with Britain. The Protestant and Catholic (or Roman Catholic) labels, when used in political or community contexts, have less to do with one’s religious practice and more to do with one’s political identity and sometimes may mean something about where one lives, since in parts of Northern Ireland (though not everywhere) members of the two religious groups live in highly segregated areas.

The term “community” will be used in several ways, including to denote one or other of the politicoreligious communities, the total community of Enniskillen and the surrounding areas, and the wider community of Northern Ireland. It will also be used in its generic and academic senses. The context should determine which meaning is appropriate.

THE ESSENTIAL ATTRIBUTES OF A COMMUNITY

It goes without saying that no two communities are alike, and therefore it is important to note that no two disasters are alike. It is remarkable, however, how traumatic experiences in different places happening to different people have a high degree of similarity when it comes to the impact on individual people. This reminds us that even though disasters and communities are different, people and people’s needs have a considerable degree of commonality (always remembering, of course, that we need to consider and regard people caught up in such events as individuals and to recognize that the needs and perceptions of the individual change over time).

To understand the impact of a disaster on a community, it is necessary to have some means of judging how well it can endure the impact and consequences of a major traumatic experience, and, specifically, to enumerate those characteristics of community that are inherently supportive and which, if threatened or overwhelmed, can lead to serious consequences for the community as a whole and for individuals within it. A number of concepts can provide a framework for describing and assessing the robustness of a community.

Belonging

The concept of belonging (what Simone Weil refers to as enracinement)1 is fundamental to the experience of individuals within their community. A community could be held to exist when, for reasons of geography, shared interests or values, or for some other reason, individuals believe they “belong.” In practice, we all have many belongings, such as our friendship groups, leisure and interest groups, school, religious groups, family, and our workplace. There are also the belongings of place such as the street and home in which one lives or the school or church one attends. These various belongings contribute to our overall identity with the community in which we live and are the source of meanings in our lives that affirm and give us our own identity. If one of those belongings is threatened, then we can often gain support from the others. This is very apparent when a family disintegrates through death or legal separation, and the school or workplace then becomes the constant belonging which sees us through. If, on the other hand, within the context of a major tragic experience, several or all of our belongings are disrupted or destroyed, then we become like refugees in our own community. We feel that to which we belong has been taken away (or possibly has rejected us), and we feel we are no longer part of the whole. In particularly devastating circumstances, perhaps the whole itself (i.e., the community) has disintegrated or ceased to exist in a meaningful way.

Communality

Also of relevance is the idea of “communality,” which Erikson wrote about in his study of the Buffalo Creek disaster (Erikson, 1976). Communality is the cohesive threads which positively bind a community together to create a certain, safe, and wholesome environment in which individuals can lead effective, enriching, and safe lives. Erikson points to the experience of collective trauma where “‘I’ continues to exist, although damaged and maybe even permanently changed. ‘You’ continues to exist, although distant and hard to relate to. But ‘we’ no longer exists as a connected pair or as linked cells in a larger communal body” (Erikson, p. 302). Where such links are disrupted or destroyed, then certainty and predictability are removed from the experience of the individual, leading to adverse social, emotional, and psychological consequences.

Segregating and Integrating Choices

Where communities within a community are in conflict or have divergent or conflicting values or aspirations, then the degree of integration can be gauged from the extent to which the communities or groups integrate in key areas of life. Such indicators of integration can be applied to formal arrangements that separate the communities (e.g., in Northern Ireland, the separate arrangements for education of children) and to informal choices (e.g., intermarriage; see Figure 10.1).

While some of these are institutionalized (e.g., structures and funding for education) and others have a long “lead-in” time (e.g., patterns of intermarriage probably do not change rapidly in light of significant positive social and political events and changes), others may be very sensitive indicators (e.g., participation in activities associated with the other community). These could be taken as clues to the mind of a community in the wake of a major tragic and divisive event and could help to determine in what direction a community is responding (i.e., integration or segregation).

Figure 10.1

In Northern Ireland, these patterns of behavior are probably more likely to retrench in response to negative political and violent events than to move in the direction of integration in response to positive developments. This means that painstaking work aimed at achieving integration or mutual acceptance can be rapidly undone by relatively short-lived but negative political or violent events. Conversely, it takes a lot of time to achieve little progress. Therefore, disasters that directly arise from the conflict in a divided community can have very significant negative consequences, which can take a long time to overcome. In some circumstances, the negative responses can emerge in the form of retaliation, running the risk of a cycle of violence (or other negative social or political outcomes).

These indicators of integration can be viewed as a “zip fastener” barometer of integration and acceptance on one hand or division on the other (see Figure 10.2). This obviously has implications for the perception of belonging and communality within a community.

In Northern Ireland, probably like most societies where more than one distinct cultural group shares the same space, clearly distinguishing cultural practices are maintained and practiced to sustain and assert each culture. The issue of parades by the Protestant (and unionist) Orange Order has led to conflict, most notably in recent times in 1995 and 1996. The assumed right to parade has clashed with the right asserted by Catholic (and mainly nationalist) neighborhoods not to have what they see as triumphalist and “coat trailing” demonstrations of Protestant culture. This led to the setting up of an Independent Review of Parades and Marches, led by Dr. Peter North, an Oxford professor invited by the British government in 1996 to chair the commission. The outcome of the review’s deliberations were published in January 1997 (Independent Review of Parades and Marches, 1997). The controversy over parades subsequently led to the establishment of a Parades Commission to reach decisions on contentious parades.

Another important feature of communities in conflict (and certainly a feature of Northern Ireland) is the politeness which masks conflict. In a report on sectarianism in Northern Ireland (The Report of the Working Party on Sectarianism, 1993), the following observation is made:

Polite relationships in divided societies are often uncertain and ambivalent relationships because there is usually fear and anxiety around. Polite relationships should, therefore, not be confused with trusting relationships. Relationships of trust and openness are ones in which deep disagreement and hurt can be aired, as well as positive feelings expressed. Needless to say, trusting relationships are comparatively rare across the communities in divided societies.

Figure 10.2 Chart illustrating ways of testin level of intercommunity integration and sensitivity of each area of community life to change, in response to positive and negative events.

The silence or acquiescence of a community or group of people should not be taken to mean satisfaction or contentment, particularly in communities that have been divided or where a tragedy leads to or has highlighted division. This politeness sometimes makes invisible the differences and prejudices which exist in a divided community. Gebler (1991), recording the words of someone with whom he had spoken, notes: “There’s a glass curtain here. When you first arrive you can’t see it, and many people who live here can’t see it either, or won’t. But it’s there all right, separating the two communities, only you don’t find out about it until you walk into it—bang!—and break your nose” (p. 54).

Preparation, Resilience & Competency In Coping

Three other concepts are relevant. First, there is the degree to which a community is prepared for a disaster. Preparation can take two forms. In passive preparedness, the infrastructure and reserves of a community can see it though a disaster. In active preparedness, specific preparation is made (e.g., to build defenses, store up reserves, develop contingencies, and plan for the disaster). Expectedness, where tragedy is in some way anticipated even if its precise timing and circumstances are unclear, will also be an important element of preparedness.

Second, the concept of resilience is the degree to which a community can absorb tragedy and the challenge to its practical and emotional resources. A community overwhelmed by two consecutive disasters within a short time span may not be able to regroup after the first catastrophe in time to reestablish its resilience. Likewise, communities facing a major disastrous event for the first time may not be prepared enough to cope (or to prepare for coping) when such challenges arise. Conversely, a community that has learned how to cope through preparation and experience may be very resilient in the face of threats to its existence and well-being.

Linked to the concepts of preparedness and resilience is that of competency in coping. How competently will the community and its agencies and leaders cope with the changing and unpredictable variables which accompany a disaster? How well will it deal with the threats it faces? How sensitively will the various parts of the community (e.g., statutory bodies, churches, etc.) address the implications of the disaster, and, specifically, the needs of those individuals, groups, and communities that have suffered directly?

THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE REMEMBRANCE DAY BOMBING: HOW THE COMMUNITY RESPONDED

Multiple Loss

Many of those injured and killed came from the churches in the town. The Presbyterian church located a few yards from the scene of the explosion lost five members and another individual who often frequented the church. The nearby Methodist church lost three members, and two local Church of Ireland churches lost one member each. To have a number of one’s church members killed in such a dramatic and public way was quite a terrible and chilling experience, and it placed quite a strain on the churches and especially their clergy. To have multiple funerals from your church, including those from the same family (three of which were double funerals, as three married couples were killed) also marked the seriousness and heightened the distress of it all. The funerals were deeply moving and powerful events. Thousands of people attended and walked in silence behind the hearses as they moved through the town to the graveyards. It was here that the sorrow and outrage of the community was seen and expressed. This was a community in grief. Its tears were on the solemn faces of its people.

Hierarchies of Suffering

It was perhaps in the belonging that the greatest support was derived from the churches themselves. Everyone knew what everyone else was feeling and, through the liturgy and the pastoral care, support was provided. Churches have their weaknesses, however. Sometimes people felt they should be coping better because they were Christians, and so they did not seek help. Likewise, for the very reason that everyone thought they knew what everyone else was going through, they themselves felt it was inappropriate to ask for help, as it would be asserting their needs over the needs of others. In this way, hierarchies of suffering evolved, with the bereaved deemed to be the most affected, then the injured, and then the rest. Close personal and church friends deferred their grief because they thought the grief of the families of those who had been killed must be greater.

In some of the meetings of bereaved and injured which took place within the months following the bombing, those involved in providing support sought to legitimize that suppressed suffering through acknowledgment and the giving of information about suffering, trauma, etc., with some effect. Also, the media were used to heighten awareness of the continuing grief and the pressures people were under.

The Threat to Communality

The bombing was an unexpected incident (even within Northern Ireland), but as an incident, it constituted a relatively short-lived experience of uncertainty during the few hours of the rescue and recovery. However, greater concerns emerged within hours and days as to the political and security implications of what had happened. This was linked to the context in which the bombing had taken place, namely, the political violence of the previous 19 years. This rolling disaster, where one event was superseded by the next, created a climate of expectation of further violence. Fears of reprisals were very strong in the Catholic community because of the identity of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) with that community. Within the context of civil conflict, these fears symbolized the grave dangers to communality at two levels. First, on the local level, the bombing was seen as very divisive and had the potential to disengage the Catholic community whose members would unselfconsciously have come forward to support their Protestant neighbors if the deaths and injuries had been caused by a nonpolitical cause. In fact, the distinctions between the communities would hardly have been visible in such circumstances. The second risk was the very serious danger of retaliatory attacks; and it is now known that such were planned (Bardon, 1992). Some reprisal attacks and killings were carried out, chiefly in and around Belfast, but mass murder was averted, and no reprisals were carried out locally.

With regard to integrating and segregating choices, the outcome is difficult to gauge accurately, as choices following divisive events such as the bombing are often private or masked. Nonetheless, some interesting things happened. In Northern Ireland, the education of children up to the age of 16 years (and sometimes 18 years) is highly segregated, with two parallel school systems. Since the early 1980s, attempts have been made to provide integrated schooling. Following the Remembrance Day bombing, an integrated primary school (for children up to the age of 11 years) opened in Enniskillen, followed later by an integrated college for older children. Second, a local interchurch and intercommunity body was established, called Enniskillen Together. This did not receive widespread support but has continued to exist, providing opportunities for people from different backgrounds to meet and discuss some of the sensitive religious and political matters that divide the two politicoreligious communities. It has played a part in mediating circumstances that could lead to violence (such as the contentious parades, referred to above). Less visible were the subtle changes that led to a hardening of the divisions, with an increase in mistrust. This must ultimately have influenced many individual choices, particularly those informal choices referred to earlier.

Responses That Reduced the Threat to Communality

What enabled the Catholic community to reengage in its supportive role at a local level, and what constrained the feared serious reprisals? The response of the Enniskillen total community was significant. The inherent strengths, attachments, and commitments between personal acquaintances within both communities and the more general sense of obligation and commitment from each community to the other played a key role in maintaining stability. Also, people responded in a way that transcended this terrible event, a response that was amplified by people all over Ireland and Britain and further afield. The condemnation of the bombing by the USSR was in itself significant, and many in faraway places saw and understood the violation of the Remembrance Day ceremony. There were many kind and generous responses to what had happened, and the people of Enniskillen felt very much the concern of the wider world. This was felt as an extension of the experience of belonging, and the cards, letters, and other gestures that flooded into Enniskillen were received warmly.

Of considerable significance was the response of the father of a 22-year-old nurse who was killed in the bombing. Gordon Wilson, within hours of his daughter Marie’s death, spoke to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and, in words which revealed in starkest horror the awfulness of what had happened, he spoke with tolerance and charity.

He said of his daughter’s killers: “I bear no ill-will. I bear no grudge. Dirty sort of talk is not going to bring her back to life. … Don’t ask me, please, for a purpose. I don’t have a purpose. I don’t have an answer. … It’s part of a greater plan, and God is good. And we shall meet again” (Wilson, 1990, pp. 46–47). These words and his account of the last few moments with his daughter as they lay entombed under the rubble following the explosion moved most who heard them. Significantly, as Bardon records in his History of Ulster (1991, p. 777), “loyalist paramilitaries admitted later that they were planning retaliation within hours of the Enniskillen bombing, but were halted by [Mr. Wilson’s] broadcast.” There was a tremendous response to the tragedy and to Mr. Wilson’s words. (Later Mr. Wilson was appointed to the position of Senator in the Senate, or upper house, of the Irish Parliament.)

Raphael in her book When Disaster Strikes (1986), speaks of emergent leaders who are thrown up unexpectedly in the midst of disasters to provide leadership. Mr. Wilson, while his contribution was primarily one of inspiration, established a way of responding to this terrible event at a time when many people did not know what to think and others clearly had malevolent responses in mind. This caused some problems for those most closely affected, many of whom had little time to determine their own response before the interview with Mr. Wilson was broadcast. Nonetheless, at a community and international level, his contribution was very significant. McCreary (1996) wrote in his biography of Senator Wilson (who died in June 1995) that “[His] contribution was both timely and untimely. It was timely because at a political level it reduced the risks of terrible reprisals. … On the other hand, at an emotional level his words were untimely and it was for this reason he attracted criticism” (p. 60).

The informal and “natural” responses of the communities were of considerable importance. These were particularly exemplified in the very large and solemn funerals. The churches were filled to capacity and many thousands joined in to walk behind the eight separate funerals. The Catholic community held a special evening Mass a few days after the bombing. The Chapel, also, was filled to capacity with Protestants as well as Catholics. Vigils were held at the War Memorial where the bomb had exploded. A week after the bombing, a special church service was held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin. Later, Wilson (1990) wrote,

It was as if the whole land was mourning with the families of the dead and with the injured and their families, and at the same time mourning for all the terrible tragedies, for all the hurts and heartaches, and the misunderstandings and divisions among all the peoples of this island, North and South. It was truly a nation-wide day of mourning. (pp. 63–64)

These and many other less public, personal gestures of practical and emotional support played a key part in acknowledging the losses and injuries that had been experienced and sent a clear signal of identification and support to those directly affected. These were very important responses.

The Absence of a Shared View

In spite of the widespread abhorrence of the Enniskillen bombing, there was (and remains) the problem of the absence of a shared view of the significance of the event. Some apologists for the bombing indicated that the ceremony of Remembrance Day was a paramilitary occasion and therefore a legitimate target. This was difficult to accept for those bereaved and injured and by many in the wider community, and such a view caused hurt and distress. At the other end of the politicoreligious spectrum, some conservative Protestants and extreme unionists felt that the generous responses of some of the people who had been affected by the bombing were naive and amounted to capitulation to those who were responsible for the bombing. The absence of a shared understanding of events, especially tragic events, is characteristic of divided communities. The same events are perceived differently by different participants. Even in communities not so markedly divided, when a community is challenged by a major catastrophic event, differences and tensions can emerge to create problems, and motives and actions can be misconstrued.

The Implications of Political Violence

The implications of violent experiences within the context of political strife brings with it complicating and additional features for the individual. These include:

• the sense of being used as a pawn in a political game orchestrated by fellow human beings which is over and beyond one’s control;

• the loss of a sense of trust and well-being with the world in general or with certain groups of people or places;

• the experience of betrayal, accentuated when people or their families have been targeted or set up;

• the failure of the state to protect and/or the state being the source of the afflicting violence;

• the additional and ensuing experiences that accentuate the unnaturalness of the experience of the loss (for example, the interest of the media; the politicization of the person’s experiences; the additional rituals of the churches);

• the constant reminders evoked by other incidents, especially those seen to be similar in some way;

• the rational fear of it happening again; especially, in a place as small as Northern Ireland, the limited possibilities of moving to an area considered safe results in people continuing to live in uncertainty or fear, or actually leaving the province;

• the absence of a shared view of what has happened and the distress caused by a member of one’s community being equivocal about one’s loss or injury (Bolton, 1996).

PROVIDING SUPPORT AND RESPONDING TO A COMMUNITY DISASTER

Assessing the Disaster and Its Impact on the Community

The most important element of a response to major tragic events is that of assessment. This is central to an initial and dynamic understanding of what has happened and what people’s needs are. Assessment should be iterative and carried out on a number of levels, from the informal gathering of intelligence to the strategic determination of what people’s immediate wants are and what responses are required to meet them. Some of the key areas and risk factors are summarized in Figure 10.3.

Intervention

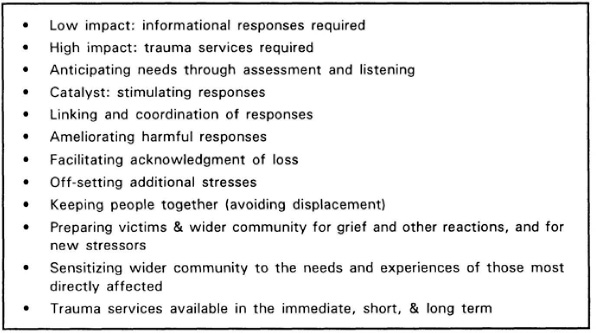

Having gained a picture of what has happened and the needs that have arisen as a result, it is then necessary to determine what action is required. Importantly, health and social services agencies and, indeed, all emergency and disaster response agencies should be extremely sensitive to the fact that they function within an environment where people already have their own support mechanisms and that other organizations and structures, which may not have a direct role in disaster management, will automatically be responding to peoples’ needs (e.g., schools and churches). However, the responses of these organizations will be variable, and the role of the health and social services agencies is to raise awareness and empower such organizations to respond appropriately (see Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.3 Assessing the impact of a disaster.

There is also the danger that these natural support mechanisms will not respond or will themselves be disengaged (as exemplified in the initial response of the Catholic community following the Enniskillen bombing). Assessment is the key. Action should be based on a determination of how the agencies charged with providing support can assist or compensate for the inadequacies of the natural support systems. Also, there needs to be a readiness to recognize, accept, and utilize the unexpected support, whether it be demonstrated through leadership, inspiration, or practical responses.

Supporting Those Affected by the Bombing

The support provided by the local health and social services department and others involved in aiding those bereaved, injured, and traumatized by the bombing was shaped to dovetail with those wider community responses. It was agreed that the initial response of the social services department should be to reinforce the existing networks and mechanisms of support within the community, such as the churches and schools. Training was arranged for teachers and others, and this was led by CRUSE Bereavement Care Northern Ireland (a voluntary organization providing bereavement counseling and support), which played a very important and supportive role in the early days. That approach, of supporting existing mechanisms, was an important strategic response that recognized the capacity of the community to care for itself, while simultaneously recognizing that it may have some weaknesses or that people may require additional support. This approach enabled control to remain within the community and its important institutions and mechanisms and did not undermine even further the community’s belief in itself. Such decisions are always finely balanced, and one can err on the side of failing to spot and respond to need or overreacting and responding too early or inappropriately, thereby robbing the community of its belief in itself to provide support and concurrently devaluing the contribution and skills of its helpers.

Figure 4 Tasks of intervention for helping agencies.

Another important task was to anticipate and head-off additional stresses. Clues were picked up as to what sorts of things were causing distress or anxiety, and steps were taken to address them. Information was provided to victims over several months through letters. The media were briefed, sometimes off-the-record, to bring them up to date and sensitize them, especially as the first anniversary approached. Attempts were made to address anxieties about the proposed memorial, by speaking with members of the Trust that had been established to manage the fund set up in response to public donations. Clergy were asked to arrange a special service on two occasions for those most directly involved. This was found to be helpful. The laying of a wreath by representatives of the bereaved (on behalf of all the bereaved families) on the anniversary date (November 8) was facilitated and coordinated for the families for the first 5 years after the bombing. A meeting with the clerk of the coroner’s court took place as proceedings were being arranged for the inquest to prepare the court and the coroner for people’s concerns. Central to all of these actions was the consultation with those affected by the bombing to determine how their concerns could be addressed. Writing on this subject, Aileen Quinton (1996), whose mother died in the Remembrance Day bombing, comments, “What can be very useful from those with appropriate skills and experience, as early a point as it can be provided, is facilitation; that is, supporting and helping local communities, including the directly affected victims, to help themselves and each other” (p. 7).

On some occasions, those who were bereaved and injured spoke out for themselves, especially through media interviews. However, in relation to some issues, for example the tensions over the form the memorial should take, some felt uncomfortable in asserting their views if they were at variance with the views of others. Such issues were mediated by others, including the present writer. This mediation of concerns, disappointments, anger, etc., can be an important task for those involved in the effort of providing support and pastoral care.

Children

The bombing was especially significant because of its impact on children. Many were present at the scene because they were laying wreaths on behalf of youth organizations or schools. Also, some children from the nearby Presbyterian Church had gone to the War Memorial as a matter of course. Then there were children who were there with their parents. In one case, the headmaster of a secondary school was very badly injured and remained in a coma long after the bombing. His school was very directly affected by the bombing.

Some excellent work was carried out by teachers to support children, and other work was done with families. Some children had profound traumatic responses and needed a great deal of support over a lengthy period of time. Examples of support included letter and essay writing, which was used as a form of debriefing for some of the children. One teacher wrote the following:

So on Wednesday (3 days after the bombing), we collected up all the little victims, these sad children whose heads were filled with horror and whose ears were ringing with the sound of screaming and of silence. We gave them paper and simply asked them to write. … They wrote fast and with great concentration … without much punctuation but with great perception. One small boy gave a sigh as he finished and pushed his paper away from him, as though he had unloaded it all. (Doherty, 1991, pp. 29–30)

Teachers also provided some counseling for some of the children. Kate Doherty, deputy principal of a local school, recalls her own work with one student. She writes,

One pupil who seemed to have recovered well from a minor injury … was to experience her worst reactions some months after the event. … When I spoke at length to this young girl it was so clear that while she had not ‘lost’ anyone in the bombing, her own sense of loss was very great. What she had lost above all was her sense of safety and security. (Doherty, 1991, p. 31)

A wide variety of interventions were used, with the most appropriate forms being identified after careful consideration of the children’s needs.

The Contribution of the Media

When the bomb exploded in Enniskillen, the media descended upon the town from across the world. Their interest was so intense and immediate that local people were following events that were literally happening outside their front doors through television and radio (for example, live broadcasts from the town on various public events that happened in the wake of the bombing). Two remote satellite stations were set up close to the bomb site by the BBC and ITN (Independent Television News), a technological novelty in 1987.

In the early days, the story of the bombing had such power and richness that it seemed that all reporters had to do was report what was happening (although I am aware of the personal difficulties and costs to some reporters of their own particular contribution). By contrast, there were some quite intrusive examples of coverage, including the entry of photographers dressed as hospital staff onto hospital wards.

Reflecting on the involvement of the media, a number of observations and lessons can be identified. First, some coverage by the media can be very intrusive, cause distress and alarm, or be inaccurate. Second, while the media are often subject to much criticism, people and communities have come to rely on newspapers, television, radio, and other media for information about their environment. Indeed, it would be difficult to consider contemporary society without the media. The media can play a very important role in providing information about important events in the life of the community (and about important events happening elsewhere). Specifically, in relation to major tragic events, the media can act as a vehicle for the transmission of experiences and feelings and can facilitate the acknowledgment of major tragic experiences and losses. Third, reflecting on the earlier discussion on hierarchies of suffering, the media can overlook people who have a story to tell or whose experiences are also worthy of acknowledgment, reinforcing experiences of victimization and powerlessness and amplifying feelings of anger and resentment. Fourth, as happened with Enniskillen, the media can convey a simplistic and stylized image of a community. In this situation, the image portrayed was of a community that was forgiving and tolerant (particularly potent images within the context of political violence). While there were a great number who felt and sometimes portrayed generous responses to their experiences, the media coverage somehow failed to deal with the anger and outrage that was (quite properly) felt by many people.

The local newspapers were able to address this much better. The national and international media, however, which had participated in the creation of an image of a forgiving community, seemed as though they were afraid to deal with other issues. This fear was understandable for two reasons. First, the response of the Enniskillen community was intrinsically dignified and generous, and to introduce what might be regarded by some as negative issues (such as anger) might have reflected badly on the media and been regarded as churlish. Second, the threats and risks were finely balanced. Any intemperate coverage by the media could have tipped the wider community into greater levels of violence. Perhaps there was a third reason. I was struck by the powerful emotional impact the bombing had on journalists, reporters, and producers. The intense drama and emotional power of the bombing and its consequences seemed to overwhelm those on whom we expect or rely on to hold up a mirror to those events which shape our lives, to an extent where their normal approach was altered.

Reflecting on these events and experiences, there is the danger, as Lahad (1988) notes, that individuals and perhaps even whole communities can become locked into a media role and image that inhibit adjustment to the tragic experience. “Survivors who become ‘familiar’ may be trapped in their newly formed public image and feel coerced to hold on to this image. Such pressures interfere with the therapeutic intervention and may postpone the necessary working-through of the mourning process” (Lahad, p. 118).

Finally, it is important to note that helping agencies and the media can collaborate to provide much needed information and support to communities and to furnish the wider society with information about what has happened and how it can and cannot support the affected community. The exercise of a proactive and collaborative relationship with key media organizations (and the clear exclusion from such arrangements of those that ignore or breach such understandings) can bring complimentary benefits to those who suffer, to the community, and to those who are seeking to provide support.

The Community Helping Itself

It is important to understand how the community can help itself. Communities can help themselves. The natural caring processes can mobilize even in the greatest adversity. These responses can be nurtured through legitimization by key people, organizations, and interests through facilitation and mediation. The care provided by the teachers quoted earlier is such an example of spontaneous and altruistic concern. Many neighbors and friends responded in similar ways. However, circumstances can conspire against such caring responses. For example, the beliefs that talking is unhelpful or that it amplifies or sustains suffering can dampen caring responses. [For an excellent exploration of organizational resistance to help, see Capewell (1996).]

Quinton (1996) comments:

The issue of control in communities is a very difficult one. … The important thing for victims is to regain some control over events relating to the disaster. What can happen is that control is assumed by community “leaders,” (e.g., clergy and priests, councilors, social services and fund trustees) and they hang on to it. This can be because they do not realize the importance of giving control to the people who have been most adversely affected. They may believe that they are relieving those suffering the most of an unnecessary burden and they honestly believe they know what the victims want or need. … There are of course, some local “leaders” who do take the trouble to check out their assumptions and to tailor their responses in line with the actual needs of the victims and to whom … it is actually a great relief that they do not have to come up with all the answers. (pp. 7–8)

Two points arise from Quinton’s observations. First, her final remark affirms the importance of helpers (clergy, local politicians, social workers, etc.) adopting roles that involve partnership with those who have suffered. Asking the question, “how can we help you?” is one of the most empowering for victim and helper alike. It involves and values the victim, while acknowledging and legitimizing the helper’s skills and their proper mobilization. Through this act of partnership, control is being returned to those who have been disempowered and disabled by their experiences. Second, Quinton’s comments raise the question, “whose is the disaster?” The disaster is a tragedy for the victims and the wider community, but in different and often conflicting ways. The implications for a town or community are predominantly social, economic, and political, and are more dispersed. The implications for victims are much more immediate, physically and emotionally, and intensely personal. These two perspectives need to be held together with due regard for both, and, in particular, for how the interests of a community can trample on the needs and interests of victims.

The natural ritual forms of expression are also important. Bolton writes (1995):

[Rituals] are engaged in to mark endings and beginnings; to honor, commemorate, remember and celebrate. They can impart meanings of significance, criticism and hope. They can express constant and essential elements, which are external to the self, but which can become internalized to give direction, perspective and consolation at a time of change and transition. … They must be authentic, relevant and timely. (p. 1)

The use of ritual, sensitive to the occasion and the needs of those involved, can be a very positive mechanism for retaining a sense of belonging and identity with the community. However, ritual can be suppressed or misused, with unhelpful outcomes. Those placed in the position of helping a community to respond to a major traumatic event can affirm the natural helping, supportive, and ritualistic mechanisms and processes within a community. Further, these mechanisms can be directed, maximized, influenced, and nudged to enable the community to begin to respond to its own needs and to facilitate the involvement of people who may not feel their needs are as great as others (Bolton, 1995).

Sometimes, however, a disaster will be so overwhelming that a community will have great difficulty helping itself. Communities and individuals may be destroyed or displaced, and the destruction of their sense of belonging may be so great that they are unable to link with each other and provide the necessary interconnections for effective support. In such circumstances, external intervention will be required to begin to rebuild a substitute sense of community and to provide the necessary initial and medium- to long-term support to enable individuals and communities to play their interacting roles with each other. To some extent, the process of peace building is about reconstructing a society which may not necessarily have had its sense of belonging destroyed but, because of the depths of its inner conflicts, has a defective mechanism and experience of belonging.

Community Maintenance and Development

On a wider front, the ability to adjust following a disaster is also about community self-confidence and its ability to transform what has been a tragedy into an opportunity for growth. Enniskillen has shown much evidence of this, with the town itself being the subject of many new commercial and architectural developments. Local people have a sense of self-confidence that was not there before. Having been in the eye of a media storm, they have become very used to visitors to the town, and many good things have been done among young people, enabling mutual understanding. Not everyone has been part of these developments, however, nor does everyone wish to be, and it is important to ensure that such improvements are at least open to everyone, even if not everyone wishes to be part of them. In the early days, the efforts were put into maintaining the community as it ran perilously close to disintegration. The efforts have now become focused on development, and the local health and social services, along with the District Council, central government, and other statutory bodies, have played an important part in this process.

Returning to one of the key words mentioned earlier, this paper concludes with some reflections on the notion of belonging and some consideration as to how it can help in the assessment of need and in determining what the appropriate responses to disaster should be. The Remembrance Day bombing challenged the belongingness of one community because of an attack perceived to come from the other. That community, in turn, felt a challenge to its belongingness as it feared a backlash. In assessing the impact of disaster, we do well to ask, “How has this event interfered with or challenged the sense of belonging that this individual, this family, this group, or this community has with its environment and with the community or context in which it lives or exists?” In determining our response to disasters, our approach should be aimed at minimizing the risks to people’s sense of belonging, rebuilding a sense of belonging that has been impaired, and, in extreme circumstances, helping to create a new sense of belonging. Finally, interventions should be shaped to ensure that an individual’s, family’s, group’s, or community’s sense of belonging is not further challenged by the manner in which we provide help and support.

Postscript: The Gift of Belonging

As I was preparing to write this chapter, Northern Ireland was once again experiencing intense political tensions and violence with the end of the IRA ceasefire in February 1996. In the months that followed, the political and intercommunity tensions grew, culminating in serious tensions and street violence surrounding a stand-off between loyalist Orange (Protestant) marchers and the police (the Royal Ulster Constabulary) at Drumcree, near Portadown, in County Armagh. The Orange marchers wanted to parade along a road adjacent to which live mainly Roman Catholic residents, some of whom objected to the march. The police blocked the march, resulting in a stand-off which lasted over 4 days and nights and which ended when the police ultimately permitted the march to go along the road, to the strong objections of the local residents. The stand-off became a matter of principle for the Orange Order, and members across Northern Ireland became involved. During the stand-off, Orange Order members set up road blocks and held demonstrations across Northern Ireland, creating havoc, disruption, and fear. People had to move from their homes following intimidation and threats. Following the march of the Orange Order members, there was rioting in some nationalist areas over a number of days in outrage at the decision to allow the march along the contested route. In the days, weeks, and months that have followed, many Roman Catholic people have withdrawn their support from Protestant businesses, resulting in financial threats to businesses and further tensions.

Looked at from the perspective of belonging, these events demonstrated clearly that the experience of belonging is as much a “gift” of the wider or other community or communities, as it is a natural phenomenon or natural consequence of community living. The gift of making a community feel it belongs can be withdrawn and is not to be presumed. In a conflict situation, especially where there is a majority community and one or more minority communities, the withdrawal of the gift of belonging can be perceived as a threat, engendering a sense of exclusion for a minority and causing destabilization for a majority.

The withdrawal of the gift by political or social forces is likely to be more profound in its consequences for relationships than the loss of a sense of belonging arising from a natural disaster, for instance. The politeness that holds communities with competing objectives together is easily eroded in such circumstances. The risk of intercommunity tensions and strife are greatly increased and the reestablishment of trust will take a long time and require much evidence to occur.

Bardon, J. (1992). A history of Ulster. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Blackstaff.

Bolton, D. (1995). The role of ritual, symbols, and meanings in psychological and community adjustment following civil conflict. In Grief & Bereavement: Proceedings from the Fourth International Conference on Grief & Bereavement (pp. 1–8). Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish National Association for Mental Health.

Bolton, D. (1996). When a community grieves; the Remembrance Day bombing, Enniskillen. In C. Mead (Ed.), Journeys of discovery. London: National Institute of Social Work.

Capewell, A. (1996). Planning an organizational response. In J. Elsegood (Ed.), Working with children in grief and loss (pp. 73–96). London: Bailliere Tindall.

Doherty, K. (1991). The Enniskillen Remembrance day bomb, 8 November, 1987. Pastoral Care, 8, 29–33.

Erikson, K. T. (1976). Everything in its path: Loss of communality at Buffalo Creek. American Journal of Psychiatry, 133(3), 302–305.

Gebler, C. (1991). The glass curtain. London: Abacus.

Independent review of parades and marches. (1997, January). Belfast, Northern Ireland: The Stationery Office.

Lahad, M. (1988). Community stress prevention. Kiriat Shmona, Israel: The Community Stress Prevention Centre.

McCreary, A. (1996). Gordon Wilson: An ordinary hero. London: Marshall Pickering.

Quinton, A. (1996). After the disaster. Welfare World, 1, 5–9.

Raphael, B. (1986). When disaster strikes. London: Hutchinson.

The Report of the Working Party on Sectarianism. (1993). Sectarianism: A discussion document for presentation to the Irish Inter-Church Meeting. Unpublished manuscript.

Weil, S. (1987). The need for roots. London: Ark.

Wilson, G. (with McCreary, A.). (1990). Marie: A story from Enniskillen. London: Marshall Pickering.

1Simone Weil was a French mystic and philosopher (1872–1943) who wrote a book, The Need for Roots, at the request of General de Gaulle towards the end of the World War II. Her work addressed the duties and privileges of the French nation at peace. She was particularly concerned about “uprootedness” or, in her terms, deracinement. The original title of her work was L’enracinement: Prelude a use declaration des devoirs envers l’etre humain (1949, Paris: Gallimard). It has been translated into English under the title. The need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Toward Mankind, by A. Wills (New York: Putnam, 1952). I have chosen the word “belonging” to encapsulate a similar theme and because of its appropriateness to the experience of a community in adversity. “Belonging” is not a literal translation; enracinement, in this context, could best be translated “rootedness,” or “the experience of being rooted.” The text used here was published by Ark, London, 1987.