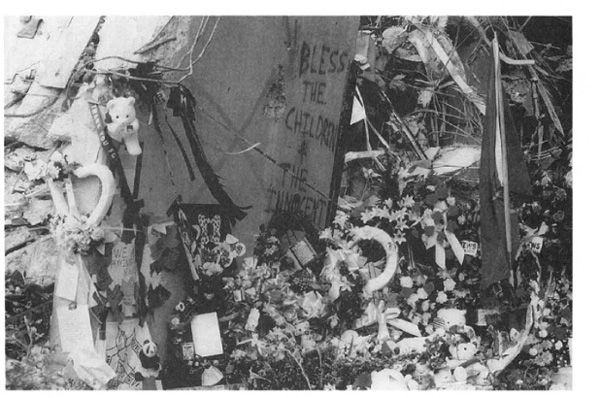

Figure 9.1 Gifts of stuffed animals, flowers, and flags are laid against a fallen slab of concrete from the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City a few days after the April 19, 1995 bombing. Written upon the concrete are the words, “Bless the Children + the Innocent.” (Personal photo of the author.)

The Terrorist Bombing in Oklahoma City

It was the most deadly terrorist bombing in American history. On Wednesday, April 19, 1995, a blast from thousands of pounds of fuel oil and fertilizer ripped through the nine-story Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in an instant, tearing a huge crater from the street to the roof. A red-orange fireball lit the sky as the north side of the building dissolved. What remained of the building looked monstrous, spitting cable and concrete onto the plaza below while gas, smoke, and dust filled the sky. Layer after layer of the building collapsed and pancaked one onto the other as ceilings crashed onto the floors below. Desks, chairs, file cabinets, refrigerators, and potted plants were thrown into the street in a tangle of wires, steel, and concrete. Toys from the children’s daycare center located on the second floor scattered everywhere. Reverberations from the blast shattered windows throughout the city; and glass fell like sharp rain over whole sections of the city, literally covering the streets for blocks and blocks throughout the downtown area. Parking meters were ripped from the ground, roofs collapsed, and metal doors twisted around themselves. Cars parked on the street crumbled, flipped, and burst into flames. Hundreds of frantic people streamed out of nearby office buildings, with blood-matted hair, cut faces, and clothes in bloody shreds. There was no screaming; just quiet terror showed in their faces.

All over Oklahoma City, people felt the force of a blast. Some thought it was a sonic boom; others, a gas explosion. Those who were trained to respond to an emergency—doctors, nurses, police, firefighters—dropped whatever they were doing and rushed to the scene. As police and firefighters located the site of the explosion, the scale of the devastation astounded them. Gradually, there was the sickening recognition that a daycare center was located in the building.

“Hundreds of individual acts of heroism and initiative—dealing with grim life-or-death decisions—were carried out in the first hour” (Irving, 1995, p. 34). Scores of untrained individuals swarmed to the building in an attempt to help while hundreds of people mobilized at the bomb site in search of family members and friends. About 90 minutes after the blast, an alarm sounded that there was a second bomb, and everyone was ordered to leave the building. Some rescuers, in the middle of extricating victims, at first refused to retreat. They agonized over leaving trapped victims, many of whom pleaded with them not to go; but they were ordered to get out a second time. This hiatus in the search lasted for about 45 minutes before rescuers could return to the victims they felt they had abandoned. Several had died.

Out of the chaos emerged an organized rescue effort. For example, a makeshift triage site was quickly set up at the building, and victims were tagged as minor, moderate, critical, or dead. The firemen brought out so many dead that a temporary morgue was established. Rescuers reported that they kept laying one dead child beside the next. Within 30 minutes of the explosion, local hospitals activated their emergency plans and began receiving hundreds of casualties. As the first wave of victims arrived in a fleet of ambulances, police cars, and vans, and personal cars driven by victims themselves, more staff were called in because a second wave of victims seemed inevitable. By the end of the day, four local hospitals had received 282 victims. Meanwhile, families who had members working in the Murrah building began trying to locate them. Soon, hospitals found themselves handling not only casualties but also desperate relatives.

At 7:00 p.m. that first night, a 15-year-old girl was also found alive and freed from the rubble. She was to be the last survivor removed from the building. By evening, there was no accurate count of the missing, and the worst estimates put the number in the hundreds. In desperation, families of the missing began to gather at designated centers combing lists of those hospitalized in the hope of finding loved ones. As it became increasingly clear that an organized way to account for the missing was needed, a family assistance center to collect information about the missing was established by the medical examiner’s office.

On the second day, teams of rescue specialists from other parts of the country arrived and began to work alongside local firemen and law enforcement. Rescuers, using K-9 search dogs and high-tech optical and listening devices, worked down through the layers of pancaked floors trying to detect signs of life. Literally thousands of firefighters from 57 fire departments around the country worked with Oklahoma firefighters in the tedious and painstaking search and body recovery process. Working around the clock, a cadre of 60 firefighters eventually increased to 250 individuals per shift. Searching for survivors was a dangerous and increasingly heartbreaking job. Much of the digging was done by hand for fear of upsetting the building’s precarious balance atop layers of crushed debris. Rescuers also had to contend with lightning, heavy rains, strong winds, bomb scares, and concern about building movement. Forty-eight hours later, as search crews kept working, optimism was fading. By the end of this period, there was a change in the task at hand: the search for survivors became a drawn-out search for bodies. The rescuers, however, never gave up hope of locating someone alive. The frustration of not finding any more survivors, however, was offset by the fact that the professional rescuers performed their operations without any loss of life or serious injury.

On days 3–5, debris removal became extremely slow-going. Cranes were used to lift the massive pieces of shattered concrete gingerly to avoid crushing any victims and to shore up the structure of the building to make it more safe to conduct recovery work. For the next 10 days, buckets of rubble were carried out by firefighters at a rate of 100–350 tons a day. By the 16th day of the search, the operation began to slow down. Although rescuers knew that victims remained buried near the blast crater, they had to halt their search because removal of the bodies became too dangerous.

Disaster experts had predicted that, due to the nature of the injuries sustained in the blast, no more than 80% of the victims would be identified. In fact, all were. Remains were taken first to a temporary morgue at the site. Twenty-four people, including 16 specialists from the U.S. Army, worked in this morgue. They used fingerprints, dental charts, and full-body X rays to identify bodies. DNA testing proved crucial in some of the most difficult cases (Irving, 1995).

Sixteen days after the blast, when the search effort concluded, the workers had removed 450 tons of debris. Every piece had been sifted for evidence of remains and criminal evidence. At that time, it was thought that two bodies remained in the core. These could not be extricated without endangering the entire building. It turned out, however, that there were three bodies remaining which could not be removed until after the implosion.

The Breath of Disaster

The magnitude and horror of this act of terrorism was unprecedented in America’s history. A total of 842 persons were injured or killed as a direct result of the bombing. Of these 842, 168 persons were killed, including 19 children, most from a daycare center located in the heart of the Murrah Federal Building. Ninety-eight (59%) of those killed in the blast and 140 (21%) of those injured were federal government employees. Three (2%) of those killed and 126 (19%) of those injured in the blast were state government employees. Four hundred and forty-two persons were treated in area hospitals: 83 were admitted and 359 were treated and released from emergency rooms. An additional 233 individuals were treated in private physicians’ offices. Four hundred and sixty-two people were left homeless (Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH), 1996). The bomb also damaged 312 buildings and businesses in a one-square-mile area. Damage estimates were expected to exceed $510 million due to damage to the federal building, adjacent businesses, and loss of life.

Nineteen children died in the explosion (15 children in the daycare center and 4 children visiting the building with relatives). Only five children in the daycare center survived the blast; all five were injured and hospitalized. A YMCA daycare center adjacent to the Murrah building was also severely damaged, injuring 52 children and 9 of the daycare staff (OSDH, 1996). Thirty children were orphaned and 219 children lost one parent. Many more children, both locally and across the nation, were also indirectly affected by this event due to the extensive live coverage by the media. All over America, children asked questions and reported fears and difficulty sleeping. These staggering statistics do not even begin to document how many lives were ripped apart and scarred forever by this tragedy.

RISK FACTORS IN POSTTRAUMA RESPONSES

It has been well documented that there are risk factors that place survivors and survivor groups at higher probability of experiencing posttraumatic stress, complicated bereavement reactions, and chronic trauma-related psychological problems (Smith & North, 1993). In using the Oklahoma City bombing as the point of reference for community survivorship, several risk factors emerge as important dimensions to determine the full extent and severity of the victims’ emotional reaction and the course of their emotional recovery. These factors include the nature of the act, severity of exposure, the length and success of rescue efforts, and involvement in the criminal justice system (Lord, 1996; Rando, 1993; Redmond, 1996; Weisaeth, 1994).

The literature examining the role of traumatic exposure is definitive. That is, regardless of the traumatic stressor, whether it stems from war, physical or sexual assault, or a natural disaster, it has been shown conclusively that dose-response is the strongest predictor of who will likely be most affected (Young, Ford, Ruzek, Friedman, & Gusman, 1997). People directly exposed to danger and life-threatening situations are at greatest risk for emotional impact. Thus, the greater the perceived life threat and the greater the sensory exposure (i.e., the more one sees distressing sights, smells distressing odors, hears distressing sounds, or is physically injured), the more likely that posttraumatic stress will be manifest and the more profound the experienced losses will be. In terms of group survivorship, the severity of exposure includes not only an overwhelming threat to one’s own life but also the extent to which the event touched the lives of family members. For example, if a child’s life is threatened by a traumatic event, the parents are similarly affected, as though they were also victims of the threat (Rando, 1993). Additionally, if a family member is killed or injured in a traumatic incident, other family members are likely to be at increased risk for psychological distress. They respond as if the injury has been to themselves, and they face complicated bereavement issues associated with traumatic loss.

A community-wide traumatic incident, such as this terrorist bombing, is by its very nature sudden, unexpected, and violent. It occurs suddenly and without warning, producing violent injury and death. Victims are unable to grasp the full implications of the loss or come to terms with the reality of the situation: it is inexplicable, unbelievable, and incomprehensible. Feelings of control, predictability, and security, and the assumptions, expectations, and beliefs upon which the mourner has based his or her life are violated in an instant (Rando, 1993).

The nature and severity of the psychological impact of the Oklahoma City bombing involve a complex interaction of the above factors that combine uniquely for each individual or survivor group. However, an understanding of these factors can serve as a useful guide for mental health professionals in understanding the nature and severity of the survivors’ reactions and in addressing the emotional needs of survivor groups. Each of these factors contributed to the increased risk of emotional difficulties that were seen in survivors, the families of those who died, and other victim or survivorship groups.

The Oklahoma City bombing involved a massive loss of life, including that of many young children. These traumatic deaths further involved violence, mutilation, and destruction on a level unprecedented in the United States. Sudden death arouses intense feelings of horror, shock, helplessness, and vulnerability. It has also been noted that the greater the violence, destruction, or brutality, the greater the survivor’s/mourner’s anxiety, fear, violation, and powerlessness as well as feelings of anger, guilt, self-blame, and shattered assumptions are likely to be (Rando, 1993). Mutilation, in particular, appears to distress survivors by conjuring up images of the suffering the victims presumably experienced; this results in more complicated bereavement and mourning (Rando, 1993).

The rescue and recovery effort at the bombing, as previously described, was long and painstaking. No more survivors were found after the first day of the bombing, yet the recovery and identification of bodies went on for over 2 weeks. Thus, the task of body recovery, identification, and transport involved prolonged contact with mass death and was a gruesome process. This exposure to traumatic death presents a significant psychological stress that can make victims of rescuers (Ursano, Fullerton, & McCaughey, 1994). Viewing, smelling, touching, and experiencing the grotesque over days and weeks resulted in particular difficulties for this survivor group of rescue workers. Repeatedly, rescuers expressed tremendous guilt about victims they were unable to save because they were unable to reach them in time.

The prolonged process of recovery and identification kept the families whose loved ones were unaccounted for in a state of emotional limbo. Waiting compounded the trauma and distress as families were left to contemplate their worst fears and fantasies. Without the closure of having the death confirmed, families were unable to begin grieving. When bodies are not recovered, this closure is never quite complete.

The bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building was an act of terrorism and violent crime, not a natural disaster or an accident. It was a calculated, premeditated act of mass murder and injury of hundreds of individuals. Its traumatic impact was greatly magnified by the fact that it occurred by human design. It was sudden and unpredictable and aimed at people who are in a defenseless position. Such willful and malicious acts of violence or murder are associated with more profound emotional wounds in addition to the physical wounds suffered (Bard & Sangrey, 1996). Additionally, victims often find themselves involved in an ongoing and prolonged manner with the criminal justice system. Their involvement can further aggravate and exacerbate emotional reactions and can lengthen the recovery process. Lengthy preparations interfere with the natural process of healing by keeping the traumatic event and associated losses in the forefront and by continually re-evoking the memories and feelings of the bombing. Thus, involvement in the legal system carries with it a large degree of additional stress and secondary traumatization for survivors and for family members.

THE VICTIM AND SURVIVOR GROUPS IN OKLAHOMA CITY

In a split second, thousands of individuals, the Oklahoma City community, and the nation became victims of the terrorist bombing in Oklahoma City. The effects of the bombing were widespread and devastating, creating a ripple effect that directly damaged the lives of thousands of individuals. For example, although Oklahoma City and its surrounding communities number close to 400,000 citizens, a survey of schoolchildren found that almost all of the children knew at least one person who was killed or injured in the explosion. The effects of such community-wide traumatic events extend well beyond immediate victims to include their families, their communities, and those who have responded as helpers. When there are few degrees of separation in the community, the mental health needs are intensified, and there is a collective sense of loss, associated reactions related to trauma, and disruption of routine. All become part of the “trauma and disaster community” (Ursano, Fullerton, & McCaughey, 1994).

Following the Oklahoma City bombing, different victim or survivor groups slowly emerged to form the traumatized community. These included: (a) individuals who were directly involved in the blast and survived; (b) individuals who lost a loved one in the blast, but were not directly involved in the blast itself; (c) children who survived, whose parents were victims, or who were affected as members of the community; (d) families and co-workers of those involved in the blast; (e) rescue workers, volunteers, and mental health professionals; (f) the Oklahoma City community; and (g) the nation as a whole.

The Oklahoma City bombing represented a direct attack against the federal government and, in essence, an attack against the nation. Also, with the capabilities of mass communication, the eyes of the nation were focused on the horror of the bombing; many watched it unfold live in front of their eyes. Thus, the bombing not only affected those directly involved and the stricken Oklahoma City community but reverberated throughout the country. Each survivor group had unique needs due to its particular experience of loss and trauma.

INTERVENTIONS WITH SURVIVOR GROUPS

Help for survivor groups is best understood in the context of when, where, and with whom interventions take place (Young et al., 1997). These dimensions can be used to guide effective clinical interventions following disaster. The temporal dimension of “when” may be broken down into the emergency phase, the postimpact phase, and the restoration or recovery phase. It is important to consider the point in time at which the intervention is done, where it is done, as well as the particular survivor group served. Mental health interventions need to provide phase-appropriate mental health services to survivor groups. Thus, it is important to reevaluate constantly the changing and unique needs of survivor groups and communities over time in the months and years of postdisaster recovery.

Support for Families with Missing Loved Ones: The Compassion Center

In the hours following the blast, families of the 300 people thought to be missing silently gathered in a state of anguish and shock at the First Christian Church. They were searching for answers and information. As rescue workers attempted to formulate lists of those reported to have been in the federal building, family members faced grim requests for detailed descriptions, photographs, and medical/dental records of their missing loved ones. Although chaos initially permeated the church, a multiagency effort was quickly organized to provide accurate information about the rescue effort, to facilitate the efforts of the medical examiner’s office, and to provide emotional support and assistance. This site became known as the Compassion Center (Sitterle, 1995). For 16 days, until nearly all of the death notifications of the 116 missing could be completed, the Compassion Center provided sanctuary for those keeping vigil and was the site for eventual communication of the heartbreaking news when a body was recovered and positively identified. Day by day, families waited in hope. Unfortunately, all came to the same grim end: their loved one had not survived.

As a highly complex operation, the Compassion Center involved numerous emergency and community organizations working together to respond to the overwhelming physical and psychological trauma for those with a missing loved one(s). During the days following the bombing, literally thousands of volunteers and hundreds of family members passed through the center. The medical examiner’s office, the National Guard, the military, police, clergy, the American Red Cross, the Department of Veterans Affairs Oklahoma Medical Center, the Department of Veterans Affairs Emergency Management Preparedness Office, the Department of Veteran’s Affairs National Center for PTSD, and the Salvation Army integrated and worked in a coordinated fashion to deliver immediate services. Mental health services were provided by volunteer mental health professionals with the American Red Cross. Nearly 400 mental health professionals a day worked at the multifaceted and anguishing task of providing support and solace as well as assisting with death notification to the families.

Mental health operations were guided by a number of principles (Myers, 1994). First, it was important to provide a safe and protective environment for families to share their pain with people who cared. Second, a sense of order, predictability, and structure were provided through leadership and communication at a time of overwhelming chaos and helplessness. Third, every effort was made to empower families by providing information in a truthful, respectful, and nonintrusive manner. The third principle also involved treating family members as normal people experiencing an abnormal event (Myers, 1994). Fourth, an understanding of the emotional climate and how it differed from the experience of an outsider watching on television was at the heart of the crisis intervention response at the Compassion Center. As optimism waned outside the center and the rest of the country began slowly realizing that there was virtually no hope for more survivors, the family members continued to hold vigil under what appeared to be a blanket of denial against the realization of their worst fear. It seemed critical for families to remain hopeful, to be vigilant, and not to abandon or betray their loved one until the death notification was confirmed.

Mental health services were organized into four primary functions: support services, family services, death notification, and stress management. Each mental health function was headed by a coordinator, who reported to an overall mental health supervisor overseeing the mental health services at the Compassion Center. All coordinating staff had cellular phones to facilitate communication and quick decision making.

Support Services The convergence of volunteers, motivated but often untrained or unsuited to the job at hand, is a universal phenomenon in disasters (Myers, 1994). Thousands of individuals called or simply arrived at the Compassion Center to offer assistance, creating an overwhelming logistical problem. Support services were developed to devise a system to ensure that qualified professionals were selected, to prevent unauthorized persons from entering the center, and to handle many of the pragmatic aspects that arose. This tragedy brought together volunteers who had never before worked together, had varying skill levels, and were unfamiliar with the procedures of the many organizations and agencies working at the Compassion Center. Mental health professionals were thus screened for ability and experience before they were placed in any position.

Given the stressful nature of providing death notifications, professionals with Ph.D.’s and M.D.’s, or those with extensive counseling experience with death, grief, and bereavement were selected to participate as members of the death notification teams. Individuals with debriefing experience, particularly training in critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) techniques, were recruited to staff the stress management/debriefing services. An attempt was also made to use mental health professionals from the Oklahoma City community and to place them in key coordinator positions. An extensive database was also created using information about each professional’s areas of specialty, expertise, address, hours available to volunteer, and phone numbers. A schedule was then created each day to provide coverage for all mental health functions for what was often an 18-hour day. Such coverage usually involved 200–350 mental health professionals daily.

In order to ensure that only authorized persons were entering the center, a complex identification process was developed. All Compassion Center staff and family members wore identification with color-coded name tags. Each service or organization (e.g., clergy, mental health, medical, medical examiner, and media) was identified by a different color. Similarly, family members were designated with a blue dot for next-of-kin or a yellow dot for extended or immediate family members. This identification system allowed both staff and families to locate each other easily when needed. To ensure privacy and safety, the building was secured by the National Guard, the police, and the military. At no time was the media allowed into the building to meet with families; however, a separate area was arranged for the media where regular briefings were made by the medical examiner and other center staff. In this way, families could meet with the media only if and when they chose, outside the center to protect the privacy of other families.

Services in the Family Room Upon arrival at the Compassion Center, each family was assigned a mental health professional whose function it was to provide an information link between the medical examiner’s office and that family. The professional’s job was to be aware of the family’s whereabouts in case information was needed or became available. These mental health professionals worked 4-hour shifts and up to 2 shifts per day. A 2-hour break between shifts was mandatory. Mental health professionals were briefed prior to a shift as to current developments, problems, and available resources.

A family room was created to provide a meeting area for families to obtain information and support. The goal was to create a safe, protective environment to meet the physical and emotional needs of the families and to prevent intrusions from the press and outside world. An attempt was made to keep families together in a single location where they could provide support to each other and be with families who truly understood their situation. The emotional climate, particularly in the family room, was dominated by a mood of anguished waiting, emotional limbo, rapid change, and, at times, conflicting information. Attempts were made to organize and structure the family room to be responsive to the ever-changing needs of families.

As the days progressed, it became clear that the families used the Compassion Center not only as a place to wait for information but also as a place to gain emotional support and to offer support to others. Families often checked in with each other. They tended to sit in the same areas of the room each day, placing photos and mementos on the tables provided. Families became somewhat agitated if someone inadvertently moved their belongings or if their space was intruded upon in some way. Their tables seemed to provide a small degree of security in their immediate world of chaos and powerlessness. Families in the Compassion Center appeared to develop their own sense of community as they struggled to cope with and comprehend the horror that had befallen them.

The center also became a place for communities around the country to express their support and grief surrounding the bombing. Cards and posters from schoolchildren and individuals from all over the country wallpapered the room with loving support. Flowers sent from strangers decorated the tables set up as a gathering place for the families. Inside this huge room, an area was set up to provide three daily hot meals for workers and family members. A constant supply of donated sandwiches, snacks, sodas, and baked goods were also available to families and staff. An area was established for families to make private phone calls using donated long distance service. Additionally, a cellular phone company donated hundreds of portable phones to families so they could be reached quickly if they left the center to go home or to work.

One corner of the room was set aside as a Children’s Corner, filled with stuffed animals, crayons, paints, toys, videotapes, and floor mats. This separate area was also a visible part of the room, allowing children to venture into their own activities but still remain physically close to their caretakers. It allowed parents to take needed time away from their children to deal with their own feelings or to provide assistance to the medical examiner’s office. The children’s corner was always staffed by a mental health professional with expertise in working with children.

As the days of waiting increased, activities were developed to provide structure, distraction, and opportunities to be physically active for the children. Animals were a part of these healing activities. Local mental health professionals with certified pet therapy animals, including rabbits, a sheltie, a Dalmatian, and an infant spider monkey named “Charlie,” staffed the room. Many of the children at the center were withdrawn or hyperactive, feeling as vulnerable as their parents. The opportunity to care for and play with pet therapy animals helped them engage and focus and engendered their sense of control.

Another invaluable intervention for the families was the help of victim advocate, Victoria Cummock, whose husband was murdered in the 1988 terrorist bombing of Pan Am Flight 103. She met with families, offering comfort, support, and her personal experience. She visited homes, read stories to the children, and provided advice to both the mental health staff and rescue officials (Cummock, 1995).

Use of Briefings A critical feature of family services was the establishment of an ongoing information link with the official rescue effort at the federal building to dispel rumors and provide accurate information. Regular briefings were conducted by the medical examiner’s office two or three times a day to provide updates and to answer questions. Additionally, the governor designated a state trooper to address any and all questions from the families. This uniformed representative met frequently with the families to share up-to-date information about the rescue effort. This constant link to the rescue scene had a calming effect on the families and reassured them that every effort was being made to recover their missing loved ones, to address their needs, and to keep them informed.

The Death Notification Process The notification staff was briefed on specific guidelines before participating in death notifications. One of the most devastating moments for any family is receiving notification of their loved one’s death. In an attempt to make this horrific moment more tolerable, systematic death notification procedures using trained staff were established. Proper death notification can be an important tool to support surviving family members and to facilitate the grieving process (Lord, 1996; Young, 1985).

The death notification process was clearly one of the most difficult jobs facing staff, particularly when it involved the loss of a child. The death notification team was headed by two representatives from the medical examiner’s office and included a mental health professional and a member of the clergy. All mental health professionals involved in this process were licensed psychologists and psychiatrists trained to identify problems within the notification and to respond appropriately to family members. Another component that was quickly added to each team was the presence of a mental health professional (again, a licensed psychologist/psychiatrist) with specialized training in working with children. As many families had issues related to talking or dealing with their children about the death of their loved one, this team member was a critical addition.

Once a body was recovered and positively identified by the medical examiner’s office, the file was transferred to the Compassion Center and protected by the National Guard. The family was then located and discreetly escorted to a quiet, secluded area on a separate floor in the Center. The medical examiner’s representative identified himself/herself and the next-of-kin before informing the family that their loved one had been positively identified as dead. After being notified, family members inevitably asked questions such as, “Are you sure?” “How do you know?” and “Did they suffer?” Families responded to the news differently. Many seemed relieved that the wait was finally over; others were stunned; some became hysterical.

The medical examiner’s representative responded by explaining how identifications were made and that, in most cases, the deceased had died immediately. Questions about the condition of the body and whether they could view the body were referred to funeral home representatives. The clergy member then offered a brief prayer if requested. Families were then asked to make a number of decisions about funeral home arrangements, when information could be released to the media, and whether they needed assistance in contacting other family members. Finally, the team inquired if the family needed assistance or wished to be left alone. Many families had formed a relationship with a mental health professional who had assisted them in the family room and asked for the individual to be present at the death notification. Several family members later returned to the family room to help other families with the wait and with what was to come.

Stress Management Services for Workers

The scope of human suffering at the Compassion Center was often unimaginable, creating a highly stressful and emotionally charged environment. Given the unique stresses at the center, it was critical to provide stress management services for staff members as a separate function of the overall mental health operation. Noone is immune; mental health professionals can be adversely affected by the stress of their work (Myers, 1994; Mitchell & Dyregrov, 1993). They are also normal people reacting to abnormal events. No one is ever fully prepared for the anguishing tasks and heartbreaking exposure to human suffering that were experienced during those weeks. This service was staffed by a coordinator and other mental health professionals experienced in disaster mental health and critical incident stress debriefing/management (CISD/CISM) techniques (Mitchell & Bray, 1990).

Defusings were frequently employed by staff working at the center. Lasting 20–25 minutes, these sessions are short versions of the more formal debriefing process and are intended for a small group (Young et al., 1997). All mental health and volunteer staff at the center were required to participate in a defusing after serving their shift each day. Defusings were held every hour so that staff could attend when convenient. Structured as a conversation about a particularly distressing event, the defusing contained three main components: introduction of the process, description of each person’s role and his/her reactions, and suggestions to protect staff from further harmful effects (Mitchell, 1983). Pamphlets and handouts on stress reduction exercises, coping strategies, and stress management were also provided to staff. Members of the stress management team were also available to address staff difficulties on an individual basis.

Additionally, members of each death notification team had a mandatory defusing immediately following each notification. To further protect these individuals from the extreme stress involved in this duty, no team member was allowed to participate in more than two notifications a day or more than four notifications overall.

Interaction Between Families and Rescue Workers

Another helpful intervention that evolved over time was the interaction between the families and the rescue workers at the federal building. Images of a ribbon held together by a guardian angel pin, a fireman hugging a family member, a child petting a search and rescue dog, and a fire chief searching the building site to find rubble for family members capture the special relationships that developed between families and rescue workers. The courage of the bereaved and the heroism of the rescuers bonded these two groups.

Clearly, one of the most difficult tasks for waiting families was not only having to wait but not being able to help directly with the rescue effort at the federal building. The bomb site was heavily secured by the military and the FBI; only authorized personnel were allowed inside the perimeter at “ground zero.” Families were therefore totally dependent upon the efforts of the rescue workers and reports from outside the center on the status of the search. To express their appreciation for the rescue workers, several of the families requested a machine to make ribbons for the firefighters and rescue workers. These families worked long hours fashioning thousands of ribbons held together by guardian angel pins. The purpose of the ribbons was to recognize workers’ valor and courage, to provide guidance and support, and to symbolize care and concern for workers’ safety and welfare during the dangerous search for bodies. The firefighters were grateful and, in fact, insisted on wearing the ribbons before entering the bombing site. One firefighter was known to have become so upset when he was unable to find his pin that he tore apart his hotel room until he found it.

Several days into the search, families made a formal request to the mental health staff to have some of the firefighters meet personally with them at the center. During the briefing before meeting with the families, the firefighters expressed concerns that the families would be angry and disappointed with them for not having rescued any survivors. Much to their surprise, the families were deeply grateful and gave them a standing ovation when they entered the room. Family members waited to touch the rescue workers, to hug them, to talk with them, and to put a face to those engaged in the search. While deeply emotional, the meeting seemed to be helpful for both the families and the firefighters.

This bond became particularly important when, 14 days into the search and recovery effort, newspapers were delivered one morning with large headline announcing, “All Hope is Gone: The Search is Over.” The firefighters were reportedly discontinuing their search, and large machinery was reportedly going to be used to search through the rubble. This news spread like a shock wave through the family room. At this point, many families had still not been notified and became hysterical that the bodies of their missing loved ones would never be recovered. To add to the turmoil, many families visualized the building site as a tomb; the thought of the remains of their loved ones being shoveled by machinery was very disturbing. To address these concerns, mental health staff arranged an emergency briefing for families to meet with the governor, the fire chief, and the police commissioner to discuss how important decisions were being made about the direction of the rescue effort. Mental health professionals consulted with officials prior to their meeting with the families and encouraged them to share information in a straightforward, truthful fashion, even though to do so was quite difficult (Cummock, 1996).

For rescue workers from around the country, the search for casualties, not survivors, became increasingly more disturbing. Even rescue dogs were reported to be “depressed” and had adverse reactions to finding so many dead bodies. What appeared to make their efforts all the more difficult was the loss of so many children. In addition to the supportive work and the defusings at the Compassion Center, many of the rescue squads made visits to the relocated YMCA daycare center. Here they were able to interact with injured children. The children needed to interact with the rescue workers, the firefighters, and their dogs as much as the adults and animals needed the contact with them. Many of the men left with tears in their eyes. They stated that the visits helped them to feel rejuvenated and better able to handle the emotional roller-coaster they had been experiencing.

Mental health professionals learned an important lesson from these experiences. Although the survivors and victims of a terrorist act may be one of the more obvious groups in need of services, those working at the scene are deeply affected as well. The need for contact with survivors, the families of the dead, and young children seems as important to the grieving process for rescue workers as is their contact with mental health professionals. Furthermore, the contact with these heroes of the hour appeared to aid in the grieving and coping process of those directly affected by a sudden traumatic incident of this magnitude.

Services for Children

The loss of so many children and their families’ anguish brought home most vividly the horror of the Oklahoma City terrorist bombing. The darkest part of the Oklahoma tragedy lies in the wreckage of the Federal building day care center. If the random and senseless destruction of a government building shows a nation how vulnerable it is, the random murder of so many innocent children at one time and in one place reveals how deep the pain can be.

If there were to be a bright side to the horror of the bombing, it was the survival of the children in the YMCA daycare center next door to the Alfred P. Murrah Federal building. With the force of the blast, all the windows in the adjacent building were shattered, metal doors came unhinged and crumpled, and the ceiling rained down on the children below. Staff quickly evacuated the infants and young children in their care. Both the staff and children suffered multiple cuts and bruises, many needing attention at area hospitals. Fortunately, no one died or suffered serious or life-threatening injuries.

The children, parents, and staff of the YMCA quickly became their own survivors group, bonded together by their shared experiences following the bombing of the Murrah building. Mental health professionals from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center contacted the Oklahoma Office of Child Care to see if any services were needed. Within a few days of the disaster, mental health professionals were at the new location for the daycare facility at a YMCA several miles from the bomb site. Although still within Oklahoma City, the center was relatively isolated from other buildings and was surrounded by trees.

Despite the move to a more ideal environment, symptoms associated with trauma were evident in all these children. The age of each child appeared to affect how each child reacted to the trauma. Specifically, the parents of infants and infant care staff reported more sleep difficulties, more clingy behavior, and more difficulty with soothing and consoling a crying infant. In the toddler room, children also showed these behaviors as well as a heightened response to loud noises and more irritability. The increased startle response was particularly problematic for these very young children. Moreover, their new room in the YMCA was located directly below the YMCA weight room, and each time a member dropped weights in the room above, it produced a loud noise in the toddler room below. Mental health professionals noted a startle followed by a brief freeze response in both the children and the staff. Many of the children cried following the pounding noise from above. Parents also reported a change in affect in some of the children, particularly a more restricted emotional demeanor. One parent, for example, described her toddler by stating, “the sunshine has gone out of her eyes.” These characteristics are consistent with posttraumatic stress responses and symptomatology in young children following exposure to a traumatic event (Pynoos & Nader, 1990).

In children between 3 and 5 years of age, other behaviors consistent with posttraumatic stress difficulties were also observed. Regressive behaviors such as a return to a pacifier and toileting accidents were noted. These young victims also displayed more separation anxiety and sleep disturbances. Parents reported that many of the children no longer slept in their own beds, preferring to sleep with their parents instead. At the daycare center, many children were unable to rest and had problems napping. Others would only lie down if a staff member remained near their cot. Staff also reported increased clinging behaviors. Posttraumatic play was evident in almost all children in this age group. Examples included repeated play with police, fire, and rescue hats and riding on toy motorcycles.

Startle responses were similarly observed in the older children. As the Oklahoma City community and the nation grieved over the smallest victims of the bombing, older children appeared to find solace and comfort in the fact that the children from the adjacent YMCA escaped with relatively minor physical injuries. Gifts for the daycare center as well as individual gifts for the children began pouring into the YMCA. Along with the gifts came “famous” visitors, TV cameras, and photographers. The bright lights and flashes of the media distressed many children. On the advice of the mental health professionals, much media attention was discontinued. In addition, unfortunately, the bombing was followed by a series of severe thunderstorms in the Oklahoma City area. Many of the parents reported startle reactions and emotional upset in their older children during the storms.

Children in the 3 to 5 year age group had fairly well developed verbal skills On several occasions, the children were seen and heard discussing the bombing and comparing their scars and injuries. They voiced questions about what happened, but often supplied erroneous information such as, “I got hurt; the bad man shot me.” Similarly, some children expressed concerns that the blast would reoccur. Children had to be reassured that the walls of the new YMCA center were strong and would not fall and that their new room did not have lots of windows and glass (many of the children’s injuries were due to shattered glass). However, this reassurance did not allay all the children’s fears; noted one child: “the room still has a ceiling that can fall.”

Staff members also were not immune to the effects of the bombing. Although they responded with courage and caring to their young charges at the time of the blast, they were also emotionally distressed by the terrorism. Staff reported difficulties sleeping, traumatic dreams, lability of emotions, irritability, trouble concentrating, and rumination about the bombing. Many reported a lack of interest in pleasurable activities and difficulty focusing on their work for extended periods of time.

To address the needs of the YMCA staff and children, mental health professionals from Oklahoma University Health Services Center were present on a daily basis for several months following the bombing. They held debriefings for parents of the children to allow parents to discuss their concerns and provided information about children’s and parents’ responses to trauma. Parents were also given information and practical suggestions about how to help their children and themselves cope with the immediate aftermath of this disaster. Therapists were also present in each of the children’s daycare rooms. They played with the children, aided the staff, and provided support for each area of the YMCA. They held debriefing sessions with the older children. They gave children many opportunities to talk (and to play) about what happened and what they thought about the events. They led children on walks through the YMCA and had them hit the walls and feel how strong they were. If a child became extremely upset during the day, therapists helped the child and staff.

Additionally, debriefing sessions (both individual and group) were held for the YMCA staff. These sessions enabled staff to voice their thoughts and feelings, including those they were unable to share with their family. Staff members were given individual “minisessions” throughout the day to support their efforts to cope.

An interesting group dynamic evolved during the first few weeks after the bombing. Several staff members were not at the downtown site at the time of the blast. Thus, a sense of “we” and “they” appeared to develop between the two groups. Staff involved in the bombing did not want to share their experiences with staff not involved and stated that only those directly affected could “understand.” They developed their own support group that became extremely important to several families. They looked to each other for support and confirmation of their feelings and ideas, but felt somewhat isolated from those who had not experienced the disaster.

Their group identification was also separate from those families who lost children in the federal building. In the first few months following the disaster, many of these families expressed frustration and anger that only the children from the federal building daycare center were receiving attention, monies, and gifts. They believed that their families also were entitled to all that was bestowed on families from the federal building. The families of children from the YMCA daycare center formed a close group. By the first anniversary of the bombing, many of the children had relocated their daycare arrangements. However, at the reunion of the YMCA families, the majority of the families attended the event. These shared beliefs and the shared bombing experience created a close-knit survivors group that had continued to function, albeit on an informal level, for 2 years after the bombing.

Group Support From Outside Oklahoma

Not only in Oklahoma, but all over the United States, schoolchildren reacted to the tragedy in what seemed to be an exercise in national compassion and support for the victims and the rescue workers. Children were encouraged to send messages to Oklahoma and hundreds of thousands of letters and drawings poured in to show their support. For example, one wrote: “Dear Governor Keating, I am five years old and this is my favorite stuffed animal. I thought you might know a little boy or girl who needs it more than I do. I send it with love” (Irving, 1995, p. 128). Locally, many schoolchildren also sent their support to victims and rescue workers. One eighth grade class in Oklahoma City, for example, sent lunch sacks to the rescuers, filled with snacks and messages, and a banner. Several days later, four ATF agents walked into their classroom to express their thanks. They told the children they had been encouraged by the cards and had come to say thank you. The children jumped to their feet and burst into cheers.

Their letters and drawings offering support and comfort, placed on rescuers’ pillows between shifts and at the bombing site, inspired the firefighters, police officers, and civilian volunteers throughout the toughest days of the rescue operation. Jon Hansen, the assistant fire chief of Oklahoma City, expressed the coming together of our nation’s children:

Possibly the brightest spot of all was the support offered by America’s children. Their cards, buttons, candy, and letters poured in. We placed these treasures at the disaster site, in the rest areas, and in meeting places. When we felt down or started losing hope, we had only to look around and the spirit of the nation’s children would be with us. (Ross & Myers, 1996)

RITUALS FOR SURVIVORS AND FAMILIES OF THE DECEASED

Rituals are at the core of human experience. Many universal forms of ritual allow emotions associated with grief and terror to be directed into activities that unify survivors, reaffirm life, and promote a sense of faith in the healing process. Ceremonies, vigils, celebrations, and other forms of ritual give people an opportunity to connect at a time when they feel disconnected by affirming identity, relatedness, and the social values of goodness and justice (Young, Sitterle, & Myers, 1996). Because these have an important healing power for survivors of a disaster and the grieving survivors of those that died (Myers, 1994; Rando, 1993), mental health professionals can play an important role in providing leadership and consultation to individuals, groups, and public entities regarding appropriate ritual or anniversary activities. The following rituals, some organized and others spontaneous, occurred in response to the Oklahoma City bombing.

Informal Memorial at the Bombing Site

Early in the rescue operation, someone spraypainted the words, “Bless the Children + the Innocent” on a jagged piece of concrete at the bomb site. Spontaneously, toys, flowers, sympathy cards, and notes of thanks were left by Okla-homans at street corners near the site as a tribute to victims, volunteers, and rescue workers. Later, a picture of one of the daycare victims with a card “in loving memory” came from a relative who wished it to be placed where the rescue workers could see it. These items were placed next to the concrete memorial. The memorial became a symbol to rescue personnel of all those they had hoped to save. It was later the focal point for the memorial service held for rescue workers at the close of the rescue operation.

Memorial at the Bomb Site for Families of Victims

On May 6, 1995, after the recovery effort was officially ended, a private ceremony and tour of the federal building blast site was organized for the families who had lost a loved one(s). Mental health professionals consulted with government officials and those in charge of the rescue effort and helped with the logistics of how to best meet the emotional needs of this survivor group. Immediate and extended families, close friends, and coworkers were allowed to walk close to the building and to view what happened there. Many of the families had only seen the bombing site on television and in press photos while they were waiting for news from the site. Twenty-two city buses transported families to the site, and the procession took the entire day in order to allow all to visit. There were two mental health professionals on each bus who prepared families and answered questions before they arrived at the site.

A double line of orange barricades marked the path to the concrete memorial and allowed the families to come face-to-face with the jagged, torn, and battered building and its festoons of flags representing each of the agencies and states involved in the rescue effort. Mental health professionals, American Red Cross volunteers, and chaplains lined the short route to assure privacy and support. As they moved down the path, family members stopped to stare, to point, or to weep. Faces tilted upward to scan the height of the building. Many talked in hushed voices; others took photographs. Many of the families brought flowers, wreaths, framed photos, mementos, framed prayers, and toys and stuffed animals to place at the concrete shrine in remembrance of those who had died. Local police, Oklahoma Highway Patrol officers, and members of several military branches who formed an honor guard were joined by some 70 officers representing 27 police agencies. When someone requested a piece of the rubble from the building, the fire chief himself waded into the bombing site to find chunks of the building to give to families. The Governor of Oklahoma and his wife also met with each family to offer their condolences and present them with an Oklahoma flag. It seemed important for families to return to the site and to see where their loved ones had perished. Such ritual activities appeared to help the surviving family members begin to confront the reality of the death of their loved ones and, perhaps, facilitated an important initial step in the grieving process (Rando, 1993).

The Fence and Survivor Tree

Following the bombing, visitors to the blast site left memorials, tokens of remembrance, flowers, stuffed animals, pictures, and poems on the cyclone fence erected around the ruins. After the implosion of the building, the fence remained as a beacon for the thousands who wanted to show their support and continued remembrance of the victims and families. It has also become a sacred gathering place for the community and for survivors of the bombing to remember and to mourn those who died. At the first- and second-year anniversaries, gatherings were held at the fence. (Later, hundreds would await the trial verdict of Timothy McVeigh at the fence, holding hands and each other.) The fence has become a place where ethnic, cultural, and class differences cease to matter. It has also become a symbol of healing to the community, a place where family members and members of the national community can literally hang their hopes and prayers for the victims and for the future.

Close to the fence is an elm tree disfigured from the blast that has been named the “survivor tree,” as it survived the blast while all the surrounding buildings were destroyed. Like the fence, family members, survivors, and visitors gather around this symbol of survival and hope. It was in front of this survivor tree that President Clinton spoke to survivors and rescue workers at the first anniversary of the bombing. (Similarly, following the guilty verdict at the McVeigh trial in June 1997, approximately 150 survivors and family members gathered at the tree with the Governor of Oklahoma and his wife to pour water onto the tree in a symbolic gesture of growth and healing.) In Oklahoma City, the fence with its memorabilia and the surviving elm tree, symbols of remembrance, survival, and hope, facilitate the grieving process, provide opportunities for survivor groups to gather and share their grief and support for each other, and provide avenues through which the community affirms its existence in the face of the devastating adversity and horror of the bombing.

The 1-year anniversary is an important time for individuals and communities following any traumatic event. The anniversary of a disaster can reawaken a wide range of feelings and reactions in the survivor population (Myers, 1994). The 1-year anniversary ceremonies of the Oklahoma City bombing were designed specifically for victims and survivors to be allowed onto the building site for the first time. These survivor groups actively participated in the planning process. As part of the ceremony, 168 seconds, one for each of the victims who perished in the blast, were set aside for a period of silence as thousands of people crowded into the few blocks around the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building site. The whole nation paused while the names of those murdered were read. One by one, name by name, for 20 minutes, a roll call of 168 people was recited. With each name, family members stepped into the fenced, grassy area and placed flowers, wreaths, or mementos on the site. A bugler played taps, and military salutes snapped to foreheads. Four F-14s flew overhead in the missing man formation and Oklahoma police helicopters flew by. This survivor group then left the site and walked a lined street to the convention center for a program closed to the public. Sympathetic onlookers along the sidewalks were kept at a distance from the marchers. The program included prayers from a number of local clergy and chaplains, music, and a video depicting the victims. Both the governor and the mayor spoke, as did Vice President A1 Gore. Afterwards, rescue workers and family members reunited and visited with each other at a reception closed to the public.

For some, it was their first visit to the site. One woman who lost her husband in the blast remarked: “I’m so very proud to be an American. The experience of being at the site and being able to touch the ground where he died. … It was tough.” Another man who lost his daughter said, “It was important to me—I knew the spot where her body was found. It was really important to us to leave the flowers.” Another survivor commented, “It brought back old memories, but I loved it. I’m very glad I came.”

Signs of remembrance of the Oklahoma City bombing reverberated around the country as well. Many motorists pulled off roadways at 9:02 a.m. to observe the 168 seconds of silence in memory of those murdered in the blast. Church bells rang across the nation and the buzz of activity at the stock market came to a halt.

Over the past decade, Americans have become increasingly aware of terrorism. It no longer happens in far-away places to people who seem foreign and unfamiliar. American lives have been touched by the bombings of Pan Am Flight 103, the World Trade Center in New York City, and more recently the A. P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Terrorism has a presence in our lives that is unprecedented, and Americans are no longer insulated from such destructive, devastating events. Our sense of security and our view of the world are indelibly altered by acts of terrorism. Our fearfulness and vigilance have increased with our awareness of our nation’s vulnerability.

The terrible reality of acts of terrorism such as the Oklahoma City bombing is that, unlike accidents and natural disasters, they are humanmade. They are vicious and calculated acts of murder designed to intimidate and control a group or a nation through the killing of innocent people. Terrorism involves crimes that are committed for social and political reasons against innocent people. For these reasons, careful attention must be paid to the psychological impact of terrorism.

Moreover, when compared to natural disasters, the magnitude and severity of emotional difficulties are likely to be far greater in response to terrorist incidents. This is especially true of terrorist incidents that involve large numbers of fatalities, including the deaths of many children, are the result of deliberate acts of violence, and involve a protracted rescue and recovery effort. Broad community reaction is also common in the aftermath of terrorist incidents. Incidents involving massive traumatic death are likely to lead to more prevalent immediate and long-term traumatic stress reactions and to place individuals at risk for complicated mourning. The traumatic aspects of sudden death can also add an overlay of posttraumatic symptoms that intensify the mourning experience. In situations such as Oklahoma City, there is a greater need for mental health professionals skilled in intervening with posttraumatic stress reactions as well as bereavement, and these clinicians must comprehend the complex interplay between both processes and be prepared to identify the wide range of survivor groups in need.

General Lessons Learned

The mental health response to the Oklahoma City bombing was the most extensive response to a terrorist event in the United States to date. During the emergency phase (first 2–4 weeks) of this disaster, mental health services to survivors and families of the victims were swift, efficient, and impressive. In many ways, the response could serve as a standard or model for future mass casualty or terrorist incidents. The state of Oklahoma had a mental health response team in place with preexisting relationships and experience with other local emergency response and law enforcement agencies, the American Red Cross, and the state Critical Incident Stress Management team. Additional mental health professionals with considerable experience and expertise in disaster mental health, response to mass casualty events, CISM, and trauma and loss were recruited from around the nation. These professionals augmented and provided guidance to the efforts of the local mental health community. The combination of the local and national mental health professionals helped to assure a smooth delivery of services. In addition, the placement of local experts in key leadership positions facilitated the transition of services to local individuals and agencies after the national experts departed.

The need for large numbers of trained volunteer mental health professionals in the immediate aftermath of a mass casualty incident was an important lesson learned from the tragedy in Oklahoma City. These professionals require specialized training and experience in disaster mental health, CISM, death notification, traumatic stress, and grief as well as familiarity with emergency response protocols prior to the occurrence of an incident. Similarly, it is essential that stress management services be provided to all volunteer staff, including mental health professionals, who provide services to victims and their families. There is probably a greater need for mental health professionals trained in CISM following a mass casualty incident or terrorist event than in some other critical incidents or natural disasters because of the increased level of traumatic stress and associated clinical symptomatology.

Lastly, in mass casualty incidents, there is a need for mental health professional staff with specialized training in death notification procedures and protocols. Although mental health professionals rarely, if ever, provide the actual death notification in such situations, they are often asked to participate on death notification teams or provide consultation, education, and training to other team members. Having a team member knowledgeable about child trauma-related issues also seems critical. It is the authors’ experience that few mental health professionals have had prior experience or training for this difficult and intensely emotional position. As volunteers are identified, training in this aspect of mental health services should be provided (Lord, 1996).

Interventions Focused on Survivor Groups

In the immediate aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing, a number of interventions helped to address the emotional needs of the different survivor groups. With regards to the needs of the next-of-kin awaiting official death notification, there were a number of approaches that appeared to facilitate grief and early stages of recovery. The Compassion Center was designed to provide a safe, protective environment to meet the physical and emotional needs of next-of-kin, to provide information, and to prevent intrusions from the press or outsiders. The need for safety and protection were foremost, and security provided by the military and law enforcement maintained the semipermeable membrane around this community of survivors. The families’ need for truth and official information was also a priority. Next-of-kin were provided with a direct link to the medical examiner, the rescue and recovery team members, and other key officials in charge. Briefings were held regularly and questions were answered truthfully at all points. This seemed crucial to the families, who struggled with how to make sense of this tragedy. It was imperative that families were given firsthand official information before it was released to the media, thus allowing them private time to cope with the facts prior to public consumption (Cummock, 1996). For the families to have interaction and access to those directly involved in the rescue/recovery effort also proved to be empowering to them in a chaotic situation.

Over time, the families at the Compassion Center developed their own sense of community, forming bonds with other survivors sharing their situation; some developed friendships that continue to the present. However, not all of the families found it helpful to be surrounded by others who shared the same sense of loss and grief. They preferred to wait in the privacy of their own homes for news of their missing relative. For these families and individuals who wanted to be able to move back and forth from the center, pagers and cellular phones were provided so that they could maintain contact with the Center. Mental health professionals recognized that individuals had different ways to respond to traumatic loss and were flexible in providing for these individual differences.

Another crucial element in facilitating the grief of these families was sensitivity to their protective need for denial in the early days and weeks following the bombing (Redmond, 1996). As family members waited for news on the status of a missing relative, their initial reactions were disbelief, shock, numbness, and the inability to make sense or comprehend what had happened. Given the suddenness of the bombing, they had no time to anticipate and prepare for the loss. It seemed literally too much to absorb at one time. The observed reaction in this group of survivors was consistent with what Raphael (1983) has called the “shock effect” of sudden death. For example, families talked initially of the hope of rescue. However, as the days progressed into weeks, their conversations evolved “from hope of survival to hope of recovering a body” (Cummock, 1996). Slowly, the degree of denial changed as they gradually absorbed the reality that loved ones had been murdered. The rate at which this process took place varied dramatically from one person to another, depending on the ability to deal with the degree of horror, anguish, and pain that came with the acceptance of reality (Cummock, 1996). It is essential for mental health professionals to recognize, respect, and be sensitive to the psychological protection of this denial mechanism and not to rush this process.

For the families of the deceased, the prolonged process of recovery, identification, and official death notification kept them in a state of emotional limbo. The waiting compounded the trauma and created its own form of torture as families contemplated their worst fears and fantasies. Nearly all of the families wanted to know if their loved ones had physically suffered, They also struggled with terrifying and intrusive images of the fantasies they developed from the bits and pieces of information they had about the building collapse and the difficulties that the medical examiner had in identifying bodies grossly disfigured and mutilated. As Lord (1996) points out, “people are intimately attached to the bodies of their loved ones … and they significantly mourn what happened to his or her body” (p. 30). Without the closure of having a death confirmed, the grieving process cannot easily begin. If bodies are not recovered, this closure is never quite complete and it is difficult for the mourner to take the first step of acknowledging the loss in the mourning process.

Intrusive influences such as tremendous public interest and mass media also can greatly complicate the grieving process. The surviving families of the Oklahoma City bombing were forced to face their loss and grief in public. The eyes of the entire nation and world were on them as the media provided live, unedited footage, which began to ease only after the first 3 weeks. In fact, the coverage of the first-year anniversary of the bombing was estimated to have exceeded the audience of the preceding Superbowl (American Psychological Association (APA), 1997).

It is important to honor the families’ needs for privacy and to minimize unnecessary outside intrusions to avoid compounding their loss. Also, as Cummock (1996, p. 2) points out, “once the deceased becomes a public persona entering the public domain, families have lost yet another part of that person during a time that they have not learned how to cope with their initial loss.” While some individuals wanted protection from the media, others found talking with reporters to be a helpful expression of their loss. Those in charge of coordinating mental health efforts provided for these contradictory and opposing needs. In Oklahoma City, the provision of regular briefings by the medical examiner and the accessibility of mental health “experts” helped to reduce the media’s intrusive efforts to meet deadlines and educated the media about respecting the families’ need for privacy.

Children dealing with the aftermath of sudden trauma have some unique needs (Saylor, 1993). A child’s age and level of exposure, and the coping skills of significant adults can effect a child’s experience and future adjustment to trauma and loss (Pynoos, 1993). Furthermore, children are not affected in a vacuum. Consequently, interventions must be conducted and understood within the context of families, peer groups, school groups, and communities (Eth & Pynoos, 1985; Pynoos & Nader, 1990). These systems are important points of contact for intervention with children, can strengthen the ties of group membership, and can offer support to the adults in charge as well. For children injured in a terrorist action, issues of safety, security, and routine must be quickly addressed. As parents/caretakers may also be affected directly by the traumatic event, guidance for helping them to help their children is essential.

At the Compassion Center, children remained in physical proximity to their caretakers while, at the same time, being offered a place of their own where they could engage in age-appropriate activities. Interventions with children were crisis oriented and provided practical assistance and guidance to families on how to answer questions and deal appropriately with the needs of their children. It was not advisable to provide intensive intervention to these young victims until their families had been able to adjust to their new situation.

As observed in other postimpact disaster communities, repeated acknowledgment of the common experience of grief and loss involving the community as a whole promotes and strengthens the bonds among survivor group members (Raphael, 1986; Tierney & Braisden, 1979). Similarly, key public leaders influenced the positive transformation seen within the Oklahoma City community following the bombing. These leaders focused the community on shared values and common goals, uniting them in the significance of their mutual experience of loss and bereavement. To accomplish this goal, meaningful public rituals, such as the memorial service for rescue workers, the national memorial service attended by the President, and the 1-year anniversary commemoration helped to foster a sense of hope and coming together. It has been suggested that this type of transformation within the community as a whole provides a backdrop for supporting the bereaved and helps to reconstruct the psychological life (Wright & Bartone, 1994).

Role of Community Leaders

The importance of key community leaders assuming a role of “grief leadership” in the mourning process cannot be overemphasized (Wright & Bartone, 1994). As these authors point out, “in the early period of shock and disbelief, community leaders reassure families and survivors by conveying accurate information, dispelling rumors, and providing a calm and controlled role model for others to follow.” Several key figures in Oklahoma City, including the Governor, the fire chief, and the chief medical examiner, assumed such roles and met regularly with the bereaved families at the Compassion Center. All of these key leaders actively sought out consultation with mental health professionals and worked closely with them to address the needs of surviving family members. Public acknowledgment of the loss by national leaders such as the President of the United States furthered the community’s comfort with the knowledge that the nation was grieving with them.

It is critical that school personnel and the mental health community work together to determine and provide for the emotional needs of children following a community-wide traumatic incident, as children do not have a voice to express their needs. Otherwise, this often silent group of survivors may not receive the services they need and have a more complicated and prolonged healing process than is necessary.

Following the bombing, efforts were also made to provide crisis intervention services to hundreds of schoolchildren within the Oklahoma City community through federally funded programs. Of importance in school-based interventions following a traumatic incident or disaster is the attitude of key adults in the school environment. Some of the local school principals relied on their own coping styles and ideas as yardsticks to evaluate and make decisions regarding the emotional needs of the young children in their schools. The end result was that some school leaders refused mental health services for their student population, believing that their students were not in need. This decision was made in opposition to the advice of mental health professionals who had been working with the children and in spite of the results of a survey clearly indicating that there were large numbers of children experiencing emotional difficulties (Krug et al., 1995).

At present, the federal laws designed to provide funding for the long-term emotional needs of victim groups are not adequate (APA, 1997). The conditions under which these federal funds are released for crisis intervention grants are rather narrow and seldom apply to focused mass casualty events, particularly of human design. Moreover, the intervention model supported by these grants is a brief crisis intervention model, depending largely on paraprofessionals and mental health professionals with little training in disaster, trauma, or grief counseling. While such a model can work well for most of the emotional needs arising from a natural disaster, a different model is needed to serve the long-term emotional needs that present themselves in most mass casualty or terrorist acts of the magnitude of the Oklahoma City bombing. For example, 2 years following the bombing, many of the survivors of the blast and the families of the bereaved still struggled with intense difficulties associated with traumatic stress and complicated mourning. Research on sudden, violent death describes a 4- to 7-year recovery period and acknowledges that recovery is never complete (Lehman & Wortman, 1987; Mercer, 1993). Thus, it is critical to recognize the magnitude and severity of emotional difficulties that will present following such incidents and that are likely to require specialized clinical interventions.

Therapeutic rituals also seemed to facilitate the grief and mourning of survivor groups. As Rando (1993) points out,