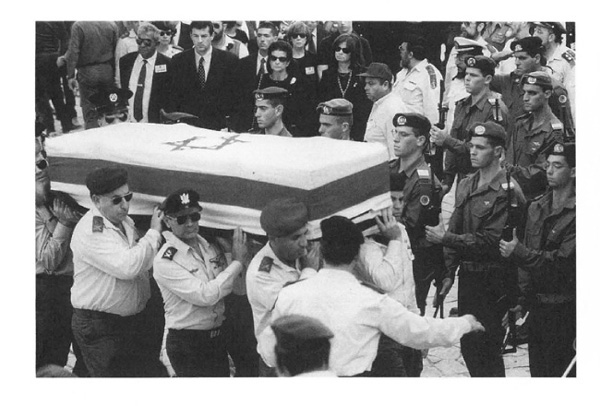

Figure 7.1 Rabin’s coffin carried by eight officers, all of whom have served or is serving as chief of staff. (Personal copy of the author; photo taken by Government Press Office, State of Israel.)

Death of a Leader: The Social Construction of Bereavement

The concept of trauma has been widely studied, both in the short- and long-term effects of adversities on individuals, families, and communities (Figley, 1988; Kleber & Brom, 1992). Trauma involving an entire nation has been little explored. A national trauma is defined as a singular catastrophic event that has a pervasive effect on the whole nation. Compared to adversities that befall individuals or families, national catastrophes have been less examined because:

1 Individual and family traumatic events by and large outnumber national traumatic events.

2 By definition, a national trauma implies a crisis situation that calls for immediate interventions rather than objective study.

3 During a national trauma, the professional person who is an observer of an event is also more than likely to be a “wounded” eyewitness (participant).

Personal accounts of those who experienced a trauma, however, are increasingly recognized as valuable documents for research purposes for gaining greater understanding and insights into the phenomena of national trauma. This chapter will offer an integration of an existing model of individual bereavement following a death event with the subjective observations of the authors as wounded professionals (Alexander & Lavie, 1993; Samuels, 1985), through an examination of the traumatic death of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995.

Three perspectives will be employed to analyze the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the reactions that followed his death. First, the individual bereavement model will be applied and compared to social collective grief. Second, a linking object model (Volkan, 1983) related to the spontaneous rituals and behaviors that took place will be used incorporating Winnicott’s (1971) transitional object. Lastly, a contextual perspective will be offered to analyze the psychosocial and cultural constructions of bereavement in traumatic loss, with a comparison to reactions that followed the death of former Prime Minister Menachem Begin and the first Israeli President, Chaim Weitzman.

BACKGROUND: BEFORE THE ASSASSINATION

The peace rally on Saturday evening, November 4, 1995, took place amidst a feeling of an unmended split within the nation over the signing of the Oslo Peace Agreement between Israeli Prime Minister Rabin and the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat. An atmosphere of instigation against Rabin preceded the rally, with increased agitation aimed at the delegitimization of the democratic political system. This reached its peak in a crowded demonstration of the parties of the political right, accompanied by posters depicting Rabin dressed in a Nazi SS uniform.

The peace rally itself was organized to demonstrate that a large part of the nation still supported the peace process, and it was planned as an evening of peace songs, with many artists performing and few speeches scheduled. A central place in the city of Tel Aviv was chosen: the Square of Kings of Israel. Thousands of people from all over the country gathered for what was seen as a successful event, both in its large turnout and in the atmosphere of people joined in singing. One of the central songs was the Song of Peace, by Ya’akov Rotblit:

Let the bright sun rise again

to light the breaking dawn

Purity in pious prayers

won’t bring back those who’ve gone.

He whose candle guttered out

who’s lying in the dust:

bitter tears won’t wake him up,

won’t bring him back to us.

No one can now raise us from

the deep and dismal pit—

salvation will not

come from victory parades

and not from psalms of praise.

So only sing out a song of peace

and not a whispered prayer.

It’s best to sing out a song for peace,

Proclaim peace everywhere.

Let the sunshine pierce the ground

through flowers on the graves.

Don’t look back, don’t turn around

for those who’ve gone away.

Do lift up your eyes in hope

not through the sights of guns.

Do not sing song of war—

but sing a song of love.

Do not say the day will come,

just make that day exist.

It is no dream and

now in all the city squares

blow trumpet blasts for peace.

So only sing out a song for peace

and not a whispered prayer.

It’s best to sing out a song for peace.

Proclaim peace everywhere. (Rotblit, 1970)

The climax of the rally came when the two present architects of peace and past political rivals—Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres—hugged each other. Rabin, known as a restrained person and an introvert, was shyly smiling and joined in the singing of the Song of Peace, reading the words from a piece of paper. The rally ended with a feeling of euphoria and with the impression that peace would continue.

Rabin folded the paper with the words of the Song of Peace, put it in his pocket as a memento, shook hands with the artists, and made his way from the back stage entrance to his car. There, an assassin made his way towards the Prime Minister, bypassed the securityman who unsuccessfully tried to shield Rabin, and shot Rabin three times in the back. Rabin fell down and, supported by his driver and securityman, was pushed into the car and rushed to the nearest hospital.

Confusion and tumult arose as soon as shots were heard. Rumors spread, and initial bulletins on the radio and television reported that there had been shots at the peace rally and that it was likely that Rabin had been wounded. Eyewitnesses interviewed gave contradictory descriptions of what had happened. Even at this early stage, there were reactions of shock and disbelief. The crowd that minutes earlier had been singing spontaneously gathered near the hospital; many remained in the square where the rally took place.

Rabin died at the hospital during surgery. He had been critically wounded and could not have been saved. The shock of those around him was total; all were at a loss. The director of Rabin’s office, a person close to him, took the initiative and wrote a few words on a piece of paper, went out to the crowd and read it repeatedly, as if not believing himself what he was reading: “In shock and sadness, the Government of Israel announces the death of its Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin.”

Trauma refers to changes of internal constructions following an external, sudden, unexpected, and unwanted event. The process that follows is that of reorganizing one’s “assumptive” world (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Parkes, 1972). Reorganization of internal turmoil, shock, and disbelief, and the external world that has changed forever are all part of the process of bereavement that the individual may experience following the traumatic death of a significant person. The more traumatic the circumstances of the death, the more intense the bereaved person’s experience is known to be, with possible difficulties in the future, especially in coming to terms with the loss. Stages, phases, or components signify the course that the bereaved person goes through, referring to its time-related dynamic: very intense emotions immediately following the loss, which decrease over time, accompanied by an increased awareness of the finality of the loss (Bowlby, 1961; Bowlby, 1980; Parkes, 1972; Ramsay, 1979; Sanders, 1982; Worden, 1991).

Although the process is universal with identified stereotyped reactions, bereavement is recognized as an idiosyncratic experience affected by, among other variables, its sociocultural context (Sanders, 1989; Stroebe, Stroebe, & Hansson, 1993; Worden, 1991). The most observable components of the process include the following:

1 Shock and disbelief that death has occurred.

2 Denial of the death and the pain and grief that follow its acknowledgment.

3 Disorientation (changes in eating and sleeping habits, social withdrawal).

4 Despair and feelings of anger and guilt over the death event.

5 Reorganization of the relationship with the deceased, from a reality-based relationship to one based on memories. Also, reorganization of one’s life, which excludes the deceased.

6 Learning new behavioral patterns adapted to life with the pain and grief associated with absence of the person who died (Bowlby, 1961; 1980).

As noted earlier, we intend to use the above model as an analogy between the individual bereavement process and the social one and as a framework within which a national trauma and the social and cultural construction of bereavement can be understood. We will refer to the first 100 days following Rabin’s assassination to examine similarities and differences between individual and collective bereavement processes.

The Funeral: Shock and Disbelief

The announcement of the assassination was followed by an intense shock reaction. Disbelief combined with a general feeling of depersonalization and derealization as to the occurrence of the event: “It couldn’t have happened!” “Such a terrible thing can’t happen to us!” It was almost midnight on Saturday night when the horrible news was announced and, from that moment onward, all television and radio networks canceled their scheduled programs and repeatedly broadcast the news of the assassination, describing over and over again the rally, especially the singing of the Song of Peace and Rabin’s last moments as he made his way towards his car. The media’s coverage also included people’s expressions of shock, disbelief, and crying. The flow of thousands of people towards the square where the assassination occurred, Rabin’s residence, and the Knesset Square where the coffin rested before the funeral was broadcast continuously, depicting a nation in grief.

Also observed was the disorientation of a nation on hearing the news of the assassination of its Prime Minister. A common reaction among individuals experiencing a sudden loss of a loved one is to search for similar events so as to comprehend the event and its circumstances. A comparable pattern was observed at the national level. For example, the media compared Rabin’s assassinations with that of President Kennedy, 32 years earlier.

Explanations and descriptions of the event by experts such as historians, sociologists, and psychologists are in themselves part of a coping mechanism for overcoming the shock of the news during the acute phase. The timing of the analysis (during the acute crisis) was extremely helpful because it helped to cognitively reconstruct what Janoff-Bulman (1992) calls “shattered assumptions.” In other words, it offered a logical explanation and some understanding of an otherwise incomprehensible behavioral phenomenon that created uncertainty. It is an identified mechanism of coping with the emotional flooding associated with uncertainty and the breaking of former assumptions.

The first few days after the assassination were dominated by expressions of shock and disbelief regarding the assassination, combined with the idealization of the Prime Minister as a martyr, in that the event of his death occurred during a proclamation for peace. A flow of youngsters filled the city square where the assassination occurred, singing and lighting candles, crying, grieving, writing songs and letters, and refusing to leave the site, in a way detached from the experts’ efforts to understand and explain the tragic death. Ironically, by doing so, the youngsters became yet another subject for analysis.

Intense shock and disbelief were also indications of the event being so sudden and unexpected, resulting in a reaction pattern that had never before been experienced in Israeli society: collective bereavement, in which the media played a crucial role. Not only did the media provide immediacy in information and offer experts’ interpretations, but it also brought the news in real time, enabling viewers to become involved in the event in a very immediate and personal way. This phenomenon was later referred to as “a live broadcast of bereavement.” Later, it became evident that all the radio and television stations acted spontaneously and intuitively, having no guidelines for such circumstances. Scheduled programs were canceled, and, instead, the assassination, the pilgrimage to the Knesset Square in Jerusalem where the coffin was laid, and the details about the funeral were broadcast nonstop, reaching a peak with the live broadcast of the funeral.

There was a sense of a momentarily harmonious community, united in its grief. Undoubtedly, the media played a central role in shaping the national bereavement pattern. Moreover, the direct and immediate reports became a bridge between the individual grief and that of the nation, giving permission to experience privately the reported and publicly observed grief, in a catharsis-like experience.

The acute phase of grief was characterized by confusion and disorientation reactions among many people whose reality perception temporarily collapsed. One example of this was the frequently repeated statement of Rabin’s office director: “I lost my country.” The words shalom chaver (“farewell, friend”), coined by President Clinton in his eulogy at the White House upon hearing the news of the assassination, best expressed these feelings and were printed as a sticker and posted everywhere.

The Funeral and the First 7 Days

The funeral was preceded by placing the coffin in the Knesset Square, holding a military ceremony, and opening the gates to those who wanted to pay a last tribute to Rabin. Tens of thousands poured into the Square throughout the day and night. The presence of dignitaries and leaders from all over the world strengthened the sense of tragic loss, reflecting that it was also felt by people outside Israel. In Israel, the nation as a whole, via the media, participated in the funeral and mourning.

Thus, shock, disbelief, and anger were the identified initial responses. These were directed by now not only towards the assassin and his family but also towards the collective “self” for its negligence in not reading early warning signs and not taking the necessary precautions to prevent the assassination. These feelings were also combined with intense sadness, pain, and a sense of togetherness which reached a peak with the funeral.

That sense of togetherness lasted only a short time, until after the shiva (according to Jewish tradition, the first 7 days of mourning). At this time, a mass assembly was held at The Kings of Israel Square, renamed as Rabin Plaza. At the same time, books, albums, and discs with songs heard at the peace rally prior to the assassination started to appear, as did massive memorial ceremonies.

The First 30 Days of Mourning: Denial and Disorientation

Though there was no question of whether to hold memorial ceremonies, it was argued, particularly by political commentators, that these were too numerous and too early in the process of a nation reorganizing itself following the traumatic event. We would like to propose that the large number of ceremonies in some way served as a sublimation for guilt feelings, as is often the case in an individual’s grief. It was also felt that the many memorial ceremonies were, in a way, the leaders’ expression of sympathy and condolence to Rabin’s family, especially to his widow, Lea. But in actual fact, by holding numerous ceremonies, the opposite effect occurred, especially as perceived by the public and the media. Combined with anger and guilt, too many ceremonies were seen as an idealization of the leader.

Articles were published describing in detail Rabin’s personality as a leader and a strategist, and, most of all, as a person representing the “beautiful and noble Israeli sabra” whose life symbolized the birth and growth of the nation. At the same time, articles, reports, and interviews in the press and on TV included accusations directed at the leaders of the opposition and the security forces for creating an atmosphere of hatred around political issues of national security and peace which had led to the strengthening of extremists who opposed the peace process. An accusatory finger was pointed at all those who kept quiet. In other words, all were guilty. Accusation and counteraccusation were additional characteristics of the nation in mourning as it debated issues concerning the failed security arrangements as well as the most appropriate ways of commemorating and remembering the Prime Minister. This was the process of sociocultural reconstruction.

The initial spontaneous responses of bringing flowers to the grave and other sites, lighting candles, writing letters and graffiti (Azaryahu & Witztum, 1996), and visiting or even remaining at the site of the assassination were turning the grave and other sites into memorial spaces (Azaryahu, 1995). Rabin Plaza, including the adjacent site of the assassination, and the front of Rabin’s residence both became spontaneous mourning sites or “emotional grounds” (Azaryahu & Witztum, 1996). There appeared to be a fundamental difference between the immediate and spontaneous responses of grief exhibited by the majority and the organized (institutionalized) public ceremonies of renaming streets and buildings in honor of Rabin that took place in later days (Azaryahu, 1995; Shamir, 1996). These rededications, such as the renaming of Beilinson Medical Center to The Rabin Medical Center, became a source of criticism for developing new myths and secular rituals in place of existing national ones.

There was also a focus on the “negative outcomes” for a grieving nation that had never before in its history experienced the assassination of its prime minister. One such example was the failure of the government to stop the massive commemoration ceremonies as well as its refraining from publicly criticizing Rabin’s widow, whose request for an office and a chauffeur brought enormous response, some in support and some against. Supporters of the government who felt guilty for not actively standing behind the assassinated Prime Minister believed that the honoring of the widow’s request was appropriate and the least the nation could do for the family. But opponents of the government felt the action to be improper. Sadness combined with anger resulted in ironical humor depicting a security mishap.

Some writers compared Rabin’s assassination to the death of yet another contemporary “mythological” Zionist figure, Joseph Trumpeldor, saying that “like Trumpeldor, Rabin, at his death and within a single moment of crystallization of historical symbols, turned into a martyr of the democratic belief” (Almog, 1995).

Three months after the assassination, commemorative activities accelerated and intensified with the publication of more books, albums, and musical recordings, and the inauguration of the Rabin Trauma Center at the hospital where Rabin was treated on the night of the assassination and from where his death was announced. Of note during this time period was the devaluation, anger, and guilt reactions that developed in parallel with the idealization process that had begun between the first and second week after the assassination.

A Year Later: The First Anniversary

In the individual model of bereavement, the end of the first year marks the symbolic end of a multidimensional process that the bereaved have gone through cognitively, emotionally, physiologically, and socially. Although we know that at this phase there is a continued preoccupation with the deceased, its intensity and quality have changed as compared to the initial response. The period that follows the process does not always signify grief resolution but is certainly an indication of the dynamic nature of the process. What are the processes that take place at the national level of grief? Are there any characteristic patterns for collective grief? Is the role of time similar to or different from that of the individual process? It probably is too early to conclude as far as Israeli society is concerned, but some comments can be made concerning the various reactions a year later.

The first anniversary was marked by a religious ceremony at Rabin’s grave. Endless discussions over the way the nation should remember and commemorate its leader took place. The word most frequently used to describe the national reaction a year later was denial. Not denial of the event itself, but denial of the circumstances of the assassination to the point of suggesting that there had been a conspiracy to kill the Prime Minister. There was also denial of the consequences of the assassination, specifically with regard to the continued increase in verbal violence as well as in the numbers of extremist groups. Some people took the rise to power of Binyamin Netanyahu and the Likud party, which were opposed to Rabin’s peace policies, in the elections following the assassination as further evidence of this denial. Overall, there seemed to be ambivalence and indecisiveness toward anything connected to the late Prime Minister.

At the same time, a year later, many were still preoccupied with the traumatic killing, visiting Rabin’s grave and the site of the assassination. The continued mourning process varied in its intensity and stage among different individuals. This diversity expressed itself in public surveys, interviews in the media, and letters to the editors of the daily newspapers. For some, refusing to accept the new reality and to reconcile with it, the grief remained acute and the pain, sharp. For others, grief had not only been for Rabin as a person and for his political way, but for the loss of an illusion as well. As one Israeli wrote in a letter to the editor, “We mourn not only for Rabin the leader, but also for ourselves and the end of an era—the era of naiveté and the break in our society, a split that may have existed before, but emerged in all its ugliness, with the shots of the assassin, and continues to follow us from that day to the present” (Michtavim Lámarechet, 1996).

STAGES OF INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL GRIEF: A COMPARISON

By using the stage model, a symbolic analogy can be drawn between the individual process of bereavement and the reactions that took place socially: shock, disbelief, idealization and devaluation, accusation and counteraccusation, and the controversy over memorial activities and their timing, intertwined with efforts to return to a routine at the public level. All are reactions frequently identified in a somewhat different form among grieving individuals. Although there exists a resemblance in the components, there are differences with the sequelae. Whereas in the individual process, these reactions characterize the first three stages, in the collective one, they appear as one, with shock, disbelief, grief, and pain being the most dominant during the first week of the acute phase, followed by disorientation and denial.

A possible source for the analogy as well as the blending of the individual and social levels is the fact that many individuals were experiencing the assassination of Rabin as a personal trauma or loss. Crying, confusion, and dysphoria were reactions noticed and reported not only by the family and close friends but also among individuals from various social groups. Kushnir and Malkinson’s (1996) survey revealed intense emotional impact (4.4 on a 5-point scale) experienced for the week following the assassination by fully employed interviewees (n = 199). The negative mood lasted for an average of 6.8 days, and lasted significantly longer among respondents who had experienced a painful loss in their families.

Perhaps the most profound difference between the individual and the collective processes of grief is the timing and function of memorialization. For the individual mourner, the mere act of commemoration has a healing effect, marking the end to a phase in one’s life and the beginning of a new one: life without the deceased. Unlike individual memorialization, the collective one reflects, more than anything else, society’s obligation to its deceased members as well as to their survivors. Hence, commemoration ceremonies can take place at any time appropriate for the purpose of preserving the complementary relationship between society and its members.

If we relate the individual and collective grief models, the massive commemoration can be seen as an indication of denial more then anything else. Commemoration ceremonies that followed the assassination of Rabin were the subject of criticism for both their timing and their range, reflecting the guilt experienced mainly by supporters of the peace process, a process that was seen as the cause of the assassination. Also, guilt was attached to the perceived negligence in not reading the situation correctly and before it was too late. Though the need to remember was unquestionable, it was felt that more time and planning would be appropriate to commemorate the memory of the leader who, more than any other, was identified with the birth of the nation. Rabin’s name had became synonymous with Israeli society. As often is the case in the individual grief process, it is likely that excessive and, at times, cynical criticism was an expression of ambivalent feelings towards the situation, the circumstances, and most of all the tragic outcome that befell the society.

As time went by, it became evident that criticism had increased and involvement with the character of the Prime Minister per se diminished, although visits to his grave continued to be massive. Based on the pattern described, an additional difference between the individual process and the collective one can be identified: not only do the pace and intensity differ, but returning to full life routine seems to be a less intense process on the collective level. Recuperating from national trauma appears to be less painful when compared to the vacuum created by the loss, never to be filled at the individual level.

CREATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF RITUALS

So far we have examined the collective expressions following a trauma from the perspective of a stage model of bereavement. Another comparison between the individual and collective levels takes us away from the temporal dimension to one related to the creation of ritualistic and symbolic mechanisms which are used to reconstruct the letting go of the dead (Turner, 1969). This approach is based on a conceptualization of transitional objects and transitional phenomena as developed by Winnicott (1971). He introduced the concept of “potential space,” which refers to an intermediate area of experiencing what lies between fantasy and reality. Specific forms of potential space include the play space, the area of the transitional object and the phenomena, the analytic space, the area of cultural experience, and the area of creativity (Ogden, 1985).

According to Winnicott, potential space is “the hypothetical area that exists between the baby and the object (mother or part of mother) during the phase of repudiation of the object as a not-me, that is, at the end of being merged in with the object” (1971, p. 107). Thus, potential space lies between the subjective object and the object objectively perceived between me-extension and not-me. The intermediate area of the potential space is the transitional area which originates in infancy, then develops to the child play space, and, in adulthood, takes the forms of cultural experience as artistic and philosophical transitional objects.

Volkan (1983) applied the concept of past phenomena and transitional objects to the area of loss and bereavement to explain the behavioral expressions of grieving people and coined the term linking object. Volkan, a psychoanalyst and a research pioneer in the field of grief and bereavement, defined a linking object as an object that becomes a source for a continuing (imagined) relationship with the deceased. Such linking objects can include real memorabilia (a watch, key, or clothes) or can be symbolic (a musical tune, a smell). All belong or are related to the deceased and, because of their relatedness, turn into precious objects for the survivor. We believe that this conceptualization can highlight and better explain the meaning of the ritualistic components that were observed during the collective bereavement process following Rabin’s death, particularly in the first few days.

Volkan (1988) is also a pioneer in bringing forth his understanding of the relationship that exists between individual and group (social) mourning processes. He described them as parallel processes, though indicating that, in the collective mourning (the group level), linking objects (real and imagined) become central in a much more dramatic way. Indeed, that was the case following Rabin’s death, where the linking objects identified were highly emotional, dramatic, and attracted much attention: lighting candles, writing songs, leaving personal belongings at the site of the assassination, and passing by his coffin. The coffin turned out to play a central role as a psychological linking object, connecting the mourning nation and the representation of its lost leader. The funeral procession to Mount Herzl (where national leaders are buried) passed through Sha’ar Ha’gay (“the gate of the valley”), an historical passage linked to the War of Independence, where many soldiers were killed in a battle over Jerusalem and where Rabin was a commander of one of the famous fighting units (Harel Division). Thus, there was an added dimension to the old tanks restored as monuments at the side of the road leading to Jerusalem. As linking objects, they became “a hot container,” a term signifying the intensity of emotions associated with its representation (the emotions provoked by the object).

The Song for Peace, which was sung on the eve of the assassination (with Rabin joining in the singing), is yet another example of a linking object. The blood-stained paper with the words of the Song for Peace printed on it, found in Rabin’s pocket on the night of the assassination, is a hot container, absorbing emotions of sadness. While some of the linking objects, like songs, candles, and graffiti, are more personal in character, others, like the Sha’ar Ha’gay passage or the grave, are more public. Some linking objects are timeless and more permanent (e.g., the grave), whereas others are transitional (e.g., the candles). All linking objects facilitate a continuing relationship with the dead person.

SOCIOPSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE: COLLECTIVE GRIEF IN ISRAELI SOCIETY

The death on April 2, 1791, of Mirabeau, the admired French politician and orator who played a central role in the early phases of French Revolution, was deeply grieved by the French, and he was given a magnificent funeral. The following is a description of the crowd awaiting the written bulletin of Mirabeau’s condition and the announcement of his death:

The people spontaneously keep silence; no carriage shall enter with noise; there is crowding pressure; but the sister of Mirabeau is reverently recognized, and has free way made for her. The people stand mute, heart-stricken; to all it seems as if a great calamity were nigh; as if the last man of France who could have swayed these coming troubles, lay there at hand-grips with the unhealthy power. The silence of a whole People, the wakeful toil of Cabanis, Friend and Physician, skills not: On Saturday, the second day of April, Mirabeau feels that the last of the Days has risen for him, that on this day he has to depart and be no more. His death is titanic as his life has been! … At half-past eight in the morning, the Doctor Petit, standing at the foot of the bed, says, “‘Il ne souffre plus.” His suffering and his working are now ended. Even so, ye silent Patriot, all ye man of France; this man is rapt away (from you. … His word you shall hear no more, his guidance follow no more. … All theaters, public amusement close; no joyful meeting can be held in these nights, joy is not for them. … The gloom is universal, never in this city was such sorrow for one death, never since that old night when Louis XII departed. … The good King Louis, Father of the People is dead! King Mirabeau is now the lost King; and one may say with little exaggeration, all the People mourn for him. (Carlyle, 1934/1837, pp. 341–342)

Clearly, there is an authentic sense of expression of deep sorrow and grief following the death of the leader. This description suggests that there exists a similar and perhaps universal pattern of response to a death of a leader, especially during the initial phase of mourning. Note, too, a resemblance to the individual pattern of reactions following a death of a significant person.

A people’s response to a death of a leader could also be viewed from a sociohistorical perspective. The construction of collective bereavement processes that took place in Israel following the assassination of Rabin are related to the sociohistorical reality in Israel. Over the years, the complementary relationship between loss as experienced by the individual and by society has changed following the various wars that have taken place in Israel. Typically, mourning patterns are determined on the collective level, and it is individuals who adopt their behavior accordingly. With societies undergoing transitions from traditional structures to more contemporary ones, individual mourning rituals are less likely to be culturally (religiously) determined, and hence it is less clear what is socially acceptable and what is not.

Elsewhere (Malkinson & Witztum, 1996; Witztum & Malkinson, 1993) we have described the place of heroism as expressed in myth-making in Israeli society. The interweaving of the personal and national response to losses in wars as reflected in memorialization vis-à-vis personal grief is interesting to observe, especially in Israel. Stages of personal grief were used as an analogy for explaining trends and changes in the development of a “national bereavement culture” involving memorialization and commemoration after the four Arab-Israeli wars.

Death of Israeli Leaders

Rabin’s assassination was compared to other critical events in Israel: the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the assassination of the Zionist leader Arlozerov, and, especially, the death of Israel’s first president, Chaim Weitzman. Not only was Weitzman admired as a person, but his role reflected, more then anything else, the rebirth of the state of Israel, with the presidency being one of its first and obvious symbols. Yet never before in the history of the nation had a prime minister been shot to death by one of his people.

In retrospect, it seems that in order to understand the mourning patterns that developed following the assassination of Rabin, it is also necessary to examine intracontextual cultural trends concerning the evolvement of collective mourning patterns following the death of other national leaders.

A more recent example is the death of former Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Bilu and Levy (1993), in their analysis of the nation’s mourning pattern, describe the initial response among Israelis following the announcement of Begin’s death and analyze the efforts to turn Begin’s figure into a myth (efforts which, according to them, were still not accomplished a year after his death at the time they published their observations). There is no question as to the different circumstances of the death of the two leaders. Begin’s death was the result of a long-standing heart ailment while Rabin’s death was the result of a traumatic assassination. Yet, when Begin’s death was announced, masses of people paid their last tribute to a beloved leader, coming to the funeral, lighting candles, and visiting his grave in what seemed like a pilgrimage to the grave of a saint. Television played a central role in bringing the event to everyone’s home by broadcasting interviews and reports about the late Prime Minister. It could be said that, in a way, television played the part of constructing the story of a leader, emphasizing his popularity as a person and a leader.

This description resembles in many ways that of the nation’s reactions when the assassination of Rabin was initially announced, despite the fundamental difference between the two leaders and the circumstances of their deaths. There were those who felt that the circumstances of Rabin’s death explained the massive reactions. Had his death been a natural one, some observers claimed, these responses would have been different, and he would not have become a myth. In both cases, however, people had a tremendous need to identify with the two leaders and to visit their graves in a ritualistic manner. Bilu and Levy (1993) describe this phenomenon as a new form of secular religion, characterized by turning the grave into a shrine: a meaningful place to visit, pray, cry, or find solitude.

As previously described, television played a central role in people’s experience of Rabin’s death, providing coverage that continued all day and throughout the night, repeating details of the assassination over and over again, coming back to the square and to the Prime Minister’s residence, and reviewing and rerunning pictures from the funeral ceremony. This was, in many ways, similar to the rumination during the acute phase of individual grief. Rumination is an identified act known to assist the person in grasping the new reality. It is the very beginning of a cognitive understanding of this new reality. Rumination also has a cathartic effect emerging from the repetitious pattern of going through the details of the death event.

The massive television coverage also resembled the one following the assassination of President Kennedy, which was watched by almost all of the United States. The media coverage of Kennedy’s assassination is viewed by many as the origin of the media as a collective authority (Zelitzer, 1992); it ushered in a new era in which the media not only delivers information in real time but also shapes the “here and now” and has a significant impact on its viewers and readers.

In all descriptions, the tendency to personify the event was evident. In many ways the expressions of sorrow, sadness, and anger at the assassin were similar to feelings experienced by individuals who have lost a close relative or a friend. A death of a leader, even from natural causes (President Roosevelt or Prime Minister Begin), seems to evoke emotional reactions of grief; but seemingly, when assassination is the cause, the initial collective emotional response appears to be intensely experienced by almost all members of society, regardless of their political affiliation. Also evident is the use of formal language conveying similar responses following the death of the leaders. A detailed report of the results of a U.S. national survey on the public reactions and behaviors following Kennedy’s assassination said that the President’s assassination seemed “to have engaged the ‘gut feeling’ of virtually every American. … [E]ven political opponents of the late President shared the general grief. Shock and disbelief were experienced by supporters as well as by opponents, a sense of loss, sorrow, anger and shame” (Sheatsley & Feldman, 1965, p. 167). Almost the exact pattern was observed in Israel following the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin, especially during the first week (Kushnir & Malkinson, 1996).

Children’s Reactions: Observed and Reported

What is the impact of a national trauma on children? It seems natural to assume that their responses would be similar to those of adults. In the assassinations of both President Kennedy and Prime Minister Rabin, the responses of children and adolescents drew attention and were the subject of studies. Following Kennedy’s assassination, children’s reactions were observed and studied particularly in relation to their political socialization (Sigel, 1965). An analysis of the responses revealed a deep involvement with the presidency in general and with the assassination in particular.

Also, a comparison of reactions of children from different age groups to those of adults indicated similar patterns of emotional and behavioral mourning reactions. The general pattern was similar to that of adults, especially among teenagers: disbelief, shock, sadness, and anger, with disbelief persisting longer among adolescents. It was suggested that disbelief could partly be related to their unreadiness at this phase of development but also to the fact that they had lost someone to whom they felt so close, an ideal parent (Wolfenstein, 1965).

Although only a few empirical studies were carried out and reported in Israel, some observations are possible. The assassination shocked people within and outside of Israel, regardless of their political affiliation. Because Prime Minister Rabin was involved in promoting the peace process, he signified for many individuals the prospect of transformation of the future to one where there would be no more wars. Thus, the mourning of the “candle children” drew special attention, not necessarily as a representative sample of Israeli youth but mainly as a group that, more than others, identified with Rabin’s efforts to promote peace. Rapoport (1996) argues that the public discussion about Israeli youth reflects first and foremost the adult expectation of the youth, an expectation that goes back historically to the myth of the “sabra.”1

Prior to the assassination, criticism had been leveled at the youngsters’ narcissistic behavior in everyday life, exhibiting lack of motivation and involvement on the national level. In contrast, after the assassination, they were praised as being sensitive youth mourning the death of their leader. Rapoport’s interviews with various nonreligious groups of young students revealed differences in attitudes among them, representing the wide range of political attitudes of the general population: Whereas some were grieving the tragic loss of Prime Minister Rabin, others were indifferent; and yet others expressed relief because they identified him as a leader who endangered Israel’s future security and even its existence by planning to give back territories. Certainly, Rapoport concludes, there were many voices among Israeli youth interpreting the assassination. The concern and fear expressed just after the assassination that the “candle children” phenomenon would eventually turn into a cult proved to be false.

THE “WOUNDED OBSERVERS”: A PERSONAL ACCOUNT

Our attempt to offer an analysis of the mourning patterns that emerged following Rabin’s assassination cannot exclude our subjective experience as wounded observers whose initial reaction was similar to that of the majority of people in Israel: one of shock and refusal to believe that the traumatic event had indeed occurred. We, too, were involved in offering explanations—a cognitive reaction to one’s shattered assumptions—as a way to make sense of a traumatic and senseless event.

Ruth Malkinson (coauthor of this chapter), in her role as the President of the Israeli Association of Marital and Family Therapy, was involved in an additional drama concerning the upcoming annual conference of the association, which was to start on the same day as Rabin’s funeral. The conference’s theme, which had been determined months earlier, was “Individuals, families and communities living in uncertainty resulting from illness, loss, unemployment and political changes,” a theme which unexpectedly turned into a timely reality following the assassination. A decision had to be made to hold or cancel the conference. This was a painful dilemma. On one hand, many other events were canceled, and, on the other, the participants in the conference could become a mini-community sharing pain and uncertainty—the very theme of the conference. The initial response favored cancellation, but at the same time Malkinson knew that many presentations dealt with the very issue of the reality that had traumatically befallen. Talks with her colleague Eliezer Witztum (coauthor of this chapter) as well as with others revealed a strong opinion in favor of holding the conference, especially given the general theme and a special session that had been planned on collective mourning, which could become a lever for legitimizing the expression of grief.

After a sleepless night as the President of the Association, Malkinson decided to recommend that the conference be held as a scientific meeting, omitting scheduled social events and allowing each person to decide whether to come or cancel. This recommendation was approved, and it was announced that the conference would take place. Interestingly, the majority of registrants came, and only about 10% requested their money back.

The first day of the conference was the day of the funeral. At the time of the funeral, all conference attendees gathered in the auditorium to watch the live broadcast of the ceremony. There we were “a weeping professional community” who had chosen to participate in the conference. There was a sense of sadness and grief, blended with closeness and a feeling of unspoken togetherness among people who represented a diverse political range. Shortly after the end of the broadcast, the scientific program resumed, and both authors took part in a symposia session entitled “Cultural Constructions of Death and Life and Its Impact on the Israeli Family,” where panelists presented their model of collective mourning in Israeli society from a psychosocial perspective. The room was full, and there was a sense of sadness and pain as people listened attentively to the presentations which not only reflected the “here and now” experience but also legitimized it. It had a cathartic quality, and people remained seated afterwards and continued to discuss the similarity between the presentation and the actual feelings they were experiencing. These strong affects lasted long after the conference ended.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND IMPLICATIONS

We have described the collective mourning patterns following the trauma using three forms of conceptualizations: two individual-based models (the bereavement stage model and the linking object) and a third model focusing on the contextual perspective to analyze the social and cultural construction of bereavement in traumatic loss. We have indicated similarities and differences between individual and collective mourning and have proposed that the components of collective mourning are a combination of the three first phases identified in the individual process.

Also, we have compared the national reactions to the deaths of two other prominent Israeli leaders, Prime Minister Menahem Begin and President Chaim Weitzman. The initial response in all three cases was that of deep grief and sorrow. We suggested that while in the three events there was a fundamental need to identify and express grief for the loss of a leader (some compare it to the loss of a father figure), the shock, disbelief, anger, and disorientation were markedly more intense following the death of Rabin. Also, in both the deaths of Begin and Rabin, television played a central role in connecting the viewers to the event and shaping the social and cultural construction of bereavement. Central in coverage of Begin’s death was the construction of his life story, his personality. This was also true in Rabin’s coverage, but there was an added element characteristic of traumatic events, that of repetitively reviewing the details of the assassination. Repeating and continually broadcasting the details of the assassination had an effect and an impact on shaping the collective responses, normalizing them, and, in a way, legitimizing expressions of pain and grief. Although these are common reactions in the individual process, in the case of Israeli society, they were viewed for many years as an antonym of heroism.

What has been the role of mental health professionals during this social tragedy? Comparing the traumatic circumstances following the death of a leader to yet another crisis in Israeli society in the past few decades reveals that there have been noticeable differences in the role of mental health professionals. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, their voice was hardly heard. After 1973, the beginning of a process of “psychologization” of Israeli society and its military had begun. The Persian Gulf War in 1990 extended this process; during this war, there was a serious crisis of leadership. The national leaders, who were at first ambivalent, vanished from the media. Mental health professionals were sucked into the vacuum that was created. Similar phenomena of less magnitude happened in the crisis after Rabin’s assassination, when psychologists, clinicians, and “bereavement specialists” were asked to explain in the media the intensity of the grief behavior, especially in children and youngsters.

The lessons regarding the duty of mental health professionals in such a national disaster should be the same as in the Gulf War (Witztum & Cohen, 1994). In addition to supplying the need for organization and early planning, they should assist by giving the public clear and authoritative information (e.g., about stress reaction and the normal grief process), explaining and providing legitimization for the anxieties, fears, sadness, pain, and strong negative feelings concerning the specific catastrophe. Nevertheless, when implementing these recommendations, it should also be noted that such legitimization must have limits and be accompanied by explicit instruction on how to maintain routine daily activities (Witztum & Cohen).

We would like, based on our observations, to conclude by referring to two otherwise contradictory components that in the case of collective mourning, may coexist. We refer to the emotional-behavioral responses of individuals following the national trauma of the assassination, which included expressions of sorrow, sadness, anger, and even crying. In contrast was the formal institutionalized response which, through massive premature commemoration ceremonies, might have reinforced a dominant pattern of denial. These may have represented and created the denial of the many complex and sensitive elements that are part of a functional process of grief. Unquestionably, more research will be needed to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of the assassination on Israeli society.

Alexander, A., & Lavie, Y. (1993). The “wounded healer:” Group co-therapy with bereaved parents. In R. Malkinson, S. Rubin, & E. Witztum (Eds.), Loss and bereavement in Jewish society in Israel (pp. 139–154). Jerusalem: Ministry of Defense Publishing House & Cana Publishing House.

Almog, O. (1995, December). Ha’Admorim Hachiloniyim. Ha’Arettz.

Azariyahu, M. (1995). Katot Le’iemiyot: Hanzchet Hanoflim Be Israel 1948–1956. State cults: Celebrating independence and commiserating the fallen in Israel 1948–1956. Beer Sheva: The Ben Gurion Research Center.

Azariyahu, M., & Witztum, E. (1996). Haunia Spontanit Shel Merhav Zikaron: Hamikre Shel Kikar Rabin. The spontaneous formation of memorial space: The case of kikar Rabin. Unpublished manuscript.

Bilu, Y., & Levy, A. (1993). The elusive sanctification of Menachem Begin. International Journal of Politics. Culture and Society, 7(2), 297–328.

Bowlby, J. (1961). The processes of mourning. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 42, 317–340.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and depression. London: The Hegarth Press.

Carlyle, T. (1934). Extracts from Carlyle’s comments on the French Revolution, originally written 1837. The Modern Library (pp. 339–350). New York: Publisher.

Figley, C. R. (1988). Towards a field of traumatic stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1, 3–6.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: The Free Press.

Kleber, R. J., & Brom, D. (1992). Coping with trauma: Therapy, prevention and treatment. Amsterdam: Swets & Zietlinger.

Kushnir, T., & Malkinson, R. (1996, June). A national level trauma: Behavioral and emotional reactions to Prime Minister Rabin’s assassination. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Studies for Stress and Trauma, Jerusalem, Israel.

Michtavim Lámaiechet, M. (1996, November). Letter to the Editor. Ha’Aretz.

Malkinson, R., & Witztum, E. (1996). Mimaash Itakasel Ve’ad. And who shall remember the dead: Psychological perspective of social and cultural analysis of bereavement. Alpayim, 12. 211–239.

Ogden, T. H. (1985). On potential space. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 66, 129–141.

Parkes, C. M. (1972). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. New York: International Universities Press.

Ramsay, R. W. (1979). Bereavement: A behavioral treatment of pathological grief. In P. O. Sjodeh, S. Bates, & W. S. Dochens (Eds.), Trends in behavior therapy (pp. 217–247). New York: Academic Press.

Rapoport, T. (1996). The many voices of Israeli youth: Multiple interpretation of Rabin’s assassination. Unpublished manuscript.

Rotblit, Y. (1970). Song of Peace. Israel: Association of Musicians and Song Writers.

Shamir, I. (1996). Zikaron ve Hanzacha. Commemoration and remembrance: Israel’s way of molding its collective memory patterns. Tel Aviv: Oved Publishers.

Sheatsley P. B., & Feldman J. F. (1965). A national survey on public reactions and behaviors. In B. S. Greenberg & E. B. Parker (Eds.), The Kennedy assassination and the American public (pp. 149–176). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the post-Jungians. London: Tavistok and Routledge.

Sigel, R. S. (1965). An exploration into some aspects of political socialization: School children’s reactions to the death of a President. In M. Wolfenstein & G. Kliman (Eds.), Children and the death of a President (pp. 199–219). New York: Doubleday.

Stroebe, M. S., Stroebe, W., & Hansson, R. O. (1993). Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research and intervention. Cambridge: University Press.

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual processes: Structure and anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine.

Volkan, V. D. (1983). Linking objects and linking phenomena. New York: International Universities Press.

Volkan, V. D. (1988). The need to have enemies and allies. London: Jason Aronson.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London: Tavistock Publication.

Witztum, E., & Malkinson, R. (1993). Bereavement and commemoration: The dual face of the national myth. In R. Malkinson, S. Rubin, & E. Witztum (Eds.), Loss and bereavement in Jewish society in Israel (pp. 231–258). Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense Publishing House & Cana Publishing House (Hebrew).

Witztum, E., & Cohen, A. A. (1994). Uses and abuses of mental health professionals on Israeli radio during the Persian Gulf War. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 25(3), 259–267.

Wolfenstein, M. (1965). Death of a parent and death of an president: Children’s reaction to two kinds of a loss. In M. Wolfenstein & G. Kliman (Eds.), Children and the death of a president (pp. 62–70). New York: Doubleday.

Worden, J. W. (1991). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. New York: Springer.

Zelitzer, B. (1992). Covering the body. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

1Sabra is the Hebrew name for prickly pear and is used to characterize the first generation of Israeli-born children following World War II and the War of Independence in 1948. It refers metaphorically to a personality with a prickly exterior and a tender interior.