CHAPTER 7

Managing Project Risk

IF YOU ARE A BUSINESS OWNER, you already understand the concept of risk: You invest your capital, time, and energy in your business in the hope that you’ll be rewarded for your efforts. Risk isn’t a bad thing; it’s the impact that the risk may have that can be painful. Calculated risk means that you’ve considered the potential for the risk event, the possible downside of the risk, and the reward that you’ll receive for managing the risk. Just as you might lose your business investment, you might reap rewards.

When project managers talk about risk, they’re talking about events, conditions, and circumstances in their work that could cause someone to get hurt, the project to be delayed, or cost overruns to occur, and that could cause the entire project to fail. There’s some uncertainty to project risks—you don’t know whether they’re likely to happen or not, but you suspect that there’s a chance of a risk event occurring. Some risks can be controlled, such as technical risks created by new materials, while other risks, such as drastic weather, you have little control over.

For business owners and project managers, there is a common theme in risk management: risk and reward. Since there are plenty of risks in every project, there must be a balance with an appropriate reward. You wouldn’t accept a risk if there was little or no reward for managing it, but you might consider a risk if the odds of it occurring were relatively low.

In a project, risk management is an ongoing process. You’ll need a risk management approach and a method for cataloging identified risk events. Depending on the size of the project’s scope, your approach could be a simple spreadsheet or a complex flowchart of risk analysis and possible outcomes. Chances are, if your projects are like most projects, you’ll find that your risks are somewhere between inconsequential and colossal. Because risk management is an ongoing process, all stakeholders are involved: the project manager, the project team, customers, the business owner, and vendors. Everyone needs to help persistently identify risk events that could hinder your project’s success.

Exploring Risk and Reward

There are two broad categories of risk: pure risk and business risk. Pure risks are events that can only hinder the project if they occur: injuries, fire, theft, and dangerous conditions. Pure risk events have no upside; they’ll only hurt the project if they aren’t accurately dealt with. Business risks, however, can have positive or negative outcomes for the project: cost savings with new vendors, time-saving techniques, the use of new materials, and investments in training. All of these examples can have a positive outcome, as they can help the project reach its objectives, or they can have a negative outcome, waste, if they don’t help the project.

The best example of a business risk is the investment in the project. When your company launches a new project, there’s an investment in the time, materials, labor, and other out-of-pocket project expenses. If the project doesn’t succeed, if the client refuses to pay for the project, or if the project team doesn’t do the work with quality, then the investment in the project is lost. If the project is successful, then the reward for the investment in it is the profit. Risk and reward go together when it comes to business risk. As you may have already realized, there is no reward for pure risk in a project.

When most project managers think about risk, they see it as a bad thing: It’s something that could keep the project from succeeding. This is a natural belief, as risk often has negative impacts on the project. There are, however, positive risk events that can bring about positive outcomes. That’s right: There are both negative and positive risk events. Negative risk events are easy to see and identify, as they threaten the project. Positive risks, however, are sometimes trickier to identify.

Positive risk events are opportunities to help the project succeed. Consider a project that needs 8,000 meters of electrical wiring. The vendor reports that the cost of the wiring will be 15 percent less if the project manager orders 10,000 meters. Even though the project manager needs only 8,000 meters, it makes sense for him to order 10,000 meters of wire and then use the remaining wire for a different project. This is a positive risk: There’s a cost savings on the material, but the risk is that the additional wiring will never actually be used in a different project.

A positive risk event is any opportunity to seize cost savings, generate better profits, complete the work better or faster, or even implement more efficient methods of managing the project. Some positive risks can actually generate more income for the organization, such as a by-product that can be sold as a result of the project work. While the project team and the project manager must always be sensitive to negative risk events, it’s important that they also look for opportunities to make the project more successful.

Identifying and Documenting Project Risk

The first component of your risk management approach is a strategy for identifying risks. Risk identification involves examining all aspects of the project to determine what conditions and events may help or hinder the project’s success. Some risks you’ll quickly identify through experience with the technology of your project. Other risk events will require more savvy and insight, such as conditions with the client, politics within your organization, and conflicting objectives among stakeholders.

The process of risk identification starts with a review of the project requirements. Your immediate goal is to document the risk events, even though some solutions may be obvious. In risk identification, you want to encourage the members of your project team to submit and share any possible risk that they can think of—nothing is banned during risk identification. You don’t want a project team member to not submit a risk because she thinks it may be silly; the submission of a tiny risk may cause someone else to see a significant risk event.

The process of risk identification isn’t a onetime event. Your project team members must always be on the lookout for risk events and communicate their discoveries. In your initial risk identification meeting, you’ll want to review all of the following documents:

![]() Activity list. What activities have pure risks and business risks? Always consider the safety of the project team by identifying any dangerous activities early in the project. Your project may not have any dangerous activities, based on the type of work you do for others. In addition to reviewing the activities for pure risks, also consider business risks. Look for any risk event that could prevent an activity from being completed—vendor delays, new types of work, conditions in the project, bottlenecked activities, and technical issues.

Activity list. What activities have pure risks and business risks? Always consider the safety of the project team by identifying any dangerous activities early in the project. Your project may not have any dangerous activities, based on the type of work you do for others. In addition to reviewing the activities for pure risks, also consider business risks. Look for any risk event that could prevent an activity from being completed—vendor delays, new types of work, conditions in the project, bottlenecked activities, and technical issues.

![]() Duration estimates. For each activity, you should have created a predicted duration. During risk identification, you should review the duration estimates to see if they’re realistic or too aggressive. You’ll also want to review activities that you’ve never attempted before, such as working with a new technology or a new piece of equipment in the project. These activities are risk-laden, as there’s little proof of how long the work will take because you’ve never tried it before.

Duration estimates. For each activity, you should have created a predicted duration. During risk identification, you should review the duration estimates to see if they’re realistic or too aggressive. You’ll also want to review activities that you’ve never attempted before, such as working with a new technology or a new piece of equipment in the project. These activities are risk-laden, as there’s little proof of how long the work will take because you’ve never tried it before.

PROJECT COACH: The first-time first-use penalty describes activities, software, materials, and resources that you’ve never tried before. You don’t know how long an activity should take until you actually do the work for the first time. The first-time first-use penalty means that you might pay more, take longer, and not get the expected outcomes on the first attempt. The results are unknown and unproven until you actually use the resource, complete the activity, or finish the task.

![]() Project cost estimates. Risks often cost the project additional funds. By examining your activities and your schedule, you’ll have good insight into the financial impact a risk may bring. You should also review the cost estimates to see if there are certain conditions that must be present for the cost estimates to be accurate, such as hitting deadlines, using cost-sensitive materials, and meeting delivery dates.

Project cost estimates. Risks often cost the project additional funds. By examining your activities and your schedule, you’ll have good insight into the financial impact a risk may bring. You should also review the cost estimates to see if there are certain conditions that must be present for the cost estimates to be accurate, such as hitting deadlines, using cost-sensitive materials, and meeting delivery dates.

![]() Project scope and work breakdown structure (WBS). The deliverables that the project is to create may be laden with risk events. Examine the project scope to see what elements require rare materials, special skill sets, or regulatory approvals or may be dependent on specific project team members. You should also examine any conditions that may alter the project deliverables, such as vendor delivery and even weather conditions.

Project scope and work breakdown structure (WBS). The deliverables that the project is to create may be laden with risk events. Examine the project scope to see what elements require rare materials, special skill sets, or regulatory approvals or may be dependent on specific project team members. You should also examine any conditions that may alter the project deliverables, such as vendor delivery and even weather conditions.

![]() Historical information and supporting details. Files and experience from past, similar projects and supporting detail from vendors, the Internet, or magazine articles can help you find risk in your project. First, historical information is one of the best sources for identifying risk events in your current project—if you’ve done similar work, you should be aware of the risks you’ve experienced. If you’re working with new materials or new types of activities, the Internet has a wealth of information that can assist you. There is risk, however, in using the Web or magazines as a resource for risk identification, as you don’t personally know who’s providing the information.

Historical information and supporting details. Files and experience from past, similar projects and supporting detail from vendors, the Internet, or magazine articles can help you find risk in your project. First, historical information is one of the best sources for identifying risk events in your current project—if you’ve done similar work, you should be aware of the risks you’ve experienced. If you’re working with new materials or new types of activities, the Internet has a wealth of information that can assist you. There is risk, however, in using the Web or magazines as a resource for risk identification, as you don’t personally know who’s providing the information.

![]() Assumptions and constraints. Assumptions are anything that you believe to be true but that you’ve not proven to be true. For example, you may have made assumptions about the technology your project team will use, the availability of resources, access to where project work will happen, and even the financing and longevity of the project. If any of these assumptions proves to be not true, then your project’s success can be diminished. Project constraints limit your options: You must use a specific material, you must do the work at the client’s site, the work must be completed by December 10, or the project costs cannot exceed $41,000. These constraints can be risks to the project, as they limit the options that you have on the project work, assignments, and even day-to-day management of the project.

Assumptions and constraints. Assumptions are anything that you believe to be true but that you’ve not proven to be true. For example, you may have made assumptions about the technology your project team will use, the availability of resources, access to where project work will happen, and even the financing and longevity of the project. If any of these assumptions proves to be not true, then your project’s success can be diminished. Project constraints limit your options: You must use a specific material, you must do the work at the client’s site, the work must be completed by December 10, or the project costs cannot exceed $41,000. These constraints can be risks to the project, as they limit the options that you have on the project work, assignments, and even day-to-day management of the project.

As you examine these project documents, you’ll need to create a risk register. The risk register is simply a database of all the risks you’ve identified in the project. A spreadsheet file actually makes a fine risk register, as you can categorize the risk events, use it throughout the risk management process, and update the status, outcomes, and lessons learned of the risk events.

For example, suppose a project team has identified a risk that there is a chance of data loss at one point in the project. You’d record this risk event and its details in the risk register. You would also associate a date with the risk and remind the team members involved at a time close to that date; then, after the risk is over, you can record the outcome of the risk. A risk register allows you to quickly record and document risk events in your project throughout the project timelines. Your current risk register can help you and others in your company manage similar projects better if you keep it updated.

While examination of the project documents is the primary approach to identifying and anticipating risk events, the members of your project team may not see a risk until they’re completing their project work. Talk with your team members, discuss their activities, and get them involved in risk identification. It’s important for the project manager to train the project team to communicate newly identified risk events when they recognize them. The communicated risk events can then be captured in the risk register and managed as part of the project.

Analyzing Risk Events

Risk analysis is the process of considering the probability, impact, and seriousness of risk. Some risk events will be tiny and won’t matter much in your project, while other events can threaten the project’s success. Most risk events that you and the project team identify will be somewhere between the two. Risk analysis, like risk identification, is an ongoing process throughout the project’s life cycle. The goal of risk analysis is to rank the risk events, quantify their impact, and prepare for risk response planning.

Once you’ve gone through a round of risk identification, it’s a good idea to organize the events based on when they’re most likely to occur. Imminent risk events should always be examined and analyzed first—you need to address these events before all other risk events. By organizing the risk events based on when they’re most likely to occur, you can analyze, monitor, and create logical responses for the events that are closest to the immediately scheduled work. It doesn’t do much good to ignore near-term risk events and focus on events that may occur at the end of the project.

The first component of risk analysis is qualitative risk analysis, which is a fast and subjective method for determining an overall risk score. Qualitative risk analysis quickly assesses the probability of the risk event, assesses its impact, and predicts how serious it may be to the project. You’ll use a risk matrix, as in Figure 7–1, to help you judge the risk. In the figure, the project manager is using an ordinal scale of very low to very high for both the probability and the impact. The combination of the score for probability and that for impact predicts the overall risk score. The higher the risk score, the more likely it is that additional analysis is needed. The results of qualitative analysis are recorded in the risk register.

Figure 7–1. Risk Matrix. A risk matrix calculates the probability and impact of a risk event to generate a risk score for each project risk event.

Qualitative analysis helps you and the project team understand the risk events, and it may be enough analysis for your project. A score of high or very high for a project risk event is an indicator that more analysis is needed. Additional analysis is called quantitative risk analysis. Quantitative risk analysis aims to quantify the risk events to predict their actual probability and financial impact. Quantitative risk analysis uses a risk matrix, too, as seen in Figure 7–2. Note that this matrix uses numerical probabilities and financial values to predict a quantified risk score.

Actually determining the probability and impact of the risk requires that you experiment, study, and research the risk event. You’ll need proof of the probability of the risk event happening and evidence of the predicted dollar amount associated with the risk impact. Quantitative risk analysis takes time, knowledge, and sometimes a budget to experiment with the materials or technologies in question.

Consider a situation in which a project team has never used a new soundproofing material before, but the project requirements call for this material to be installed throughout a 4,500-square-foot recording studio. The risk is that the project team may waste the material or install it incorrectly, which could lead to rework and liabilities for the organization and the client. The project manager needs a budget to purchase the soundproofing material to test how the material operates, to learn how to install the material, and to train the project team. The approach used in this scenario is quantitative modeling, where the risks and conditions on a smaller scale reflect what’s likely to happen on a larger scale.

Figure 7–2. Quantitative Risk Analysis. Quantitative risk analysis also uses a risk matrix, but it uses cardinal numbers to predict the probability and impact of risk events.

Another approach for quantitative risk analysis is to interview the project stakeholders based on their experience, concerns, and insight into the project work. For example, you might want to interview a skilled project team member about a risk that falls into his area of expertise in the project. You and the team member will discuss the risk event, the odds of the event happening, and what type of costs and delays may occur. This conversation not only helps you gauge the seriousness of the event, but also helps the project team member understand the risk and better control and manage his work.

Another approach, the Monte Carlo simulation, uses a software program to help find the most likely outcome of a risk event by calculating the result of every possible scenario and then predicting a mean. For example, if you elected to use three-point duration estimates for your project activities, you have an optimistic estimate, a most likely estimate, and a pessimistic estimate for each of the project activities. In the Monte Carlo simulation, you can set probabilities for each estimate for specific project activities and play “what-if” scenarios for the project duration. You might want to predict what would happen to your project duration if certain activities took the pessimistic duration, other activities took the optimistic duration, and the remaining project work took the most likely duration. The software would then calculate how long the project would take based on the probabilities you assigned.

PROJECT COACH: The Monte Carlo simulation is named after the world-famous gambling city of Monte Carlo and its games of chance. Just as when the roulette wheel is spun many times, there are multiple possible combinations of numbers on which the ball may land and of black, red, or green choices, so too does this software simulation examine every possible combination of risk outcomes to predict the events in your project.

Once you have analyzed your risks using the quantitative approach, you can add an additional step: predicting the risk exposure for the project and creating a risk contingency reserve. The risk exposure is the cost of the risks you’re exposed to based on the probability and impact of the risk events. The contingency reserve is the amount of funds you’ll need to have available to offset the risk exposure. Figure 7–3 may look like a risk matrix, but notice that it includes a summary of the risk score, also called the expected monetary value and abbreviated as Ex$V, of the risk events. The sum of all of the risk scores is the risk exposure for the project.

Check out the last risk event in the figure—it’s a positive risk event, an opportunity for a discount on project materials, so there’s a positive impact and a positive risk score for this event. You’ll also notice that the risk exposure is not all of the risk impacts, but just the sum of the risk event scores. The reason why it’s only the sum of the expected monetary values and not the total impact is because of the probability that the events will actually happen. None of the risk events has a 100 percent chance of happening; their probability is still uncertain. Basically, you’re confident about the probabilities of the risk events based on your quantitative analysis.

Figure 7–3. Expected Monetary Value. The sum of the expected monetary values helps determine the amount of funds needed for a risk contingency reserve.

Based on the risk exposure, you’ll need that amount of funds in the risk contingency reserve. The risk contingency reserve is a special budget to offset the costs of the risk events should they actually occur. In Figure 7–3, the risk contingency reserve will be $41,825. In this example, if the electrical risk and the materials risk do happen, the total cost to the project will be $43,500—more than the risk reserve. The probability that both of these events will actually happen, however, is relatively low—there’s confidence that it’s not likely that both of the events will happen.

The unease that you may feel concerning these risk events is called your utility function. Your utility function describes your emotional tolerance for risk events based on what the outcome of the risk may mean for your business, your project, and you personally. Your tolerance for risk should be balanced against the reward that the risk may bring—you don’t want to tolerate risks that aren’t worth the reward they could bring. In project management, the higher the priority of the project, the less tolerant you are of risk events. The risks that you do tolerate should have some identifiable benefit, or reward, associated with them.

PROJECT COACH: Sometimes clients ask, why not just remove all the risk from the project? You usually can’t because the cost of removing the risk events would be greater than what is reasonable. Would you spend $45,000 to remove a risk event that has a 10 percent chance of happening and an impact of $50,000? You could spend the $45,000 and be certain that the risk wouldn’t happen, or you could save your $45,000 and gamble that there’s a 90 percent chance that the risk event will not happen.

Your projects may not need a quantitative analysis of all the risk events. Chances are, though, that you’ll need to dig into some of your risk events to determine their true probability and impact so that you can better manage the project and control the risk events in it. Just as you’ll update the risk register with qualitative risk analysis, you should do the same with the outcomes of quantitative risk analysis.

Managing the risk contingency reserve is an important concept in project management. If you’ve elected to create a contingency reserve to offset the risk exposure in your project, you’ll need to analyze the distribution of risk events to anticipate the riskiest portions of your project and when you may need the funds in your risk timeline. The further along a project progresses, the odds of failure as a result of risk generally decrease.

As the project moves past certain risk events without the risk events occurring, the contingency reserve becomes more and more realistic for the remaining risk events in the project. Because you’re hedging your bets by assuming that some risks are going to happen and some risks are not, there’s logic to planning the project work based on the associated risks. If cost-laden risk events do happen early in the project, these events could deplete much of the risk contingency reserve and not leave enough funds to account for the remaining risk in the project.

In some projects, when it’s feasible, it’s best to do the activities with the most risk events first to decide whether the risks are going to actually happen. This way, you can reduce the items in the project scope for a less costly project to account for the cost of the risks. You might also try to do the riskiest work first to see if the negative event happens, and if it does, cancel the entire project rather than investing a great deal of money, only to have the project fail late in implementation. The distribution of risk and the discipline that your project centers on won’t always allow this approach, but it’s a good practice to consider.

Creating Risk Responses

As you and your project team move through the identification of the risks in your project, you’ll probably have some immediate ideas about how you might counteract some of the risks. Other risk events are likely to need more thinking, analysis, and even trial and error to find the right response to remove the risk event, lower its probability and impact, or manage its existence in your project. Creating risk responses is the process of determining the best way to manage and control the risks within your project so that they don’t impede the goals of the project.

The biggest response you can create is called your contingency plan. It’s the plan for the worst-case scenario in your project; you might also know this as your rollback plan or your recovery plan, and it describes how you can restore the environment should the project go seriously awry. Consider an IT project to implement new software at 750 workstations. If, despite all testing, the rollout of the software begins to cause problems with the computers, affect the network, and disrupt the business, the contingency plan would describe how to quickly remove the software and return the computer environment to its previous state.

Every project, regardless of the discipline and the nature of the project, should have a contingency plan. Sometimes the contingency plan must acknowledge a cutover moment—the point of no return for the project. Imagine a construction project to create a new building in your city. In this hypothetical project, the first step is to demolish the existing building and prep the site for the new construction. Once the existing building has been demolished, it will be nearly impossible to restore the environment to its previous condition. The contingency plan acknowledges these moments and takes precautions to confirm the events leading up to this cutover event.

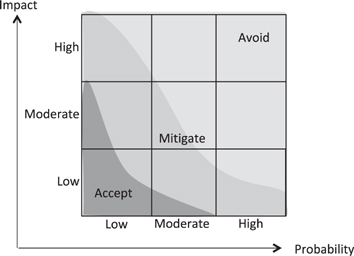

Within your project, there are likely to be risk events that are less dramatic than the idea of the cutover risk. For each risk event, you’ll need to determine whether the risk has enough probability and impact to warrant a risk response. Figure 7–4 shows the range of scores in qualitative analysis used to predict whether a risk response is needed—and what type of response. Risk events that have a low probability and a low impact are added to a low-level risk watch list that is part of the risk register. You’ll need to review this low-level risk watch list periodically to determine whether the probability and/or impact of the risk events have changed; if they have, you may need to create a risk response.

All other risk events must be responded to, controlled, and managed throughout the project. There are seven risk responses that you can use to respond to risk events. Remember, not all risk is negative, as there may be opportunities that you and the project team discover in the project that should not be ignored. Here are your choices when it comes to risk responses:

![]() Avoidance. Some of the risks in your project you’ll just want to avoid: dangerous scenarios, unrealistic schedules, vague project requirements, and even the approach your project team takes to complete the project work. To use this negative risk response, you’ll change your project management plan, change the project schedule, reduce the project scope, learn more about the work surrounding the risk event, or, in the worst-case scenario, halt the project entirely to avoid the risk event.

Avoidance. Some of the risks in your project you’ll just want to avoid: dangerous scenarios, unrealistic schedules, vague project requirements, and even the approach your project team takes to complete the project work. To use this negative risk response, you’ll change your project management plan, change the project schedule, reduce the project scope, learn more about the work surrounding the risk event, or, in the worst-case scenario, halt the project entirely to avoid the risk event.

![]() Transference. When you transfer a risk event, you’re paying someone else to manage the negative risk event for you. The risk doesn’t go away, but there’s a contractual relationship between your organization and the party that will manage the risk on your behalf. A classic example of transference is to hire a licensed electrician to do the electrical work for your project rather than assigning the dangerous work to your project team. Transference doesn’t have to be limited to dangerous work, however; you might hire a consultant to do a portion of the project because of her speed and expertise rather than risk the project being late by doing the work internally.

Transference. When you transfer a risk event, you’re paying someone else to manage the negative risk event for you. The risk doesn’t go away, but there’s a contractual relationship between your organization and the party that will manage the risk on your behalf. A classic example of transference is to hire a licensed electrician to do the electrical work for your project rather than assigning the dangerous work to your project team. Transference doesn’t have to be limited to dangerous work, however; you might hire a consultant to do a portion of the project because of her speed and expertise rather than risk the project being late by doing the work internally.

![]() Mitigation. Any attempts that you and the project team make to reduce the probability and/or impact of a negative risk event are mitigation. Mitigation is a proactive response to the risk event to remove the possibility of the risk event’s occurring or, if the event does occur, to minimize the resulting costs and delays. Consider the risk of a project that may disrupt your client’s business cycle if the project work happens in the daytime. Mitigation would be to elect to do the project work in the evenings and on weekends so as to limit the disruption for your customer.

Mitigation. Any attempts that you and the project team make to reduce the probability and/or impact of a negative risk event are mitigation. Mitigation is a proactive response to the risk event to remove the possibility of the risk event’s occurring or, if the event does occur, to minimize the resulting costs and delays. Consider the risk of a project that may disrupt your client’s business cycle if the project work happens in the daytime. Mitigation would be to elect to do the project work in the evenings and on weekends so as to limit the disruption for your customer.

![]() Exploiting. In your project, you may discover opportunities to finish the work faster, realize a cost savings, or even create a by-product as a result of the project work you’re doing for your customer. Exploiting the positive risk event involves the actions you’ll take to ensure that the opportunity is definitely realized. Consider a project to develop software for a client. As you develop the software, you realize that the software could be developed into a product that your company could sell. As long as there’s not a contractual obligation with the project customer, such as intellectual rights, this is an opportunity to create a by-product that could generate revenue beyond the current project.

Exploiting. In your project, you may discover opportunities to finish the work faster, realize a cost savings, or even create a by-product as a result of the project work you’re doing for your customer. Exploiting the positive risk event involves the actions you’ll take to ensure that the opportunity is definitely realized. Consider a project to develop software for a client. As you develop the software, you realize that the software could be developed into a product that your company could sell. As long as there’s not a contractual obligation with the project customer, such as intellectual rights, this is an opportunity to create a by-product that could generate revenue beyond the current project.

![]() Enhancing. Enhancing changes the project condition to try to make the opportunity happen. There’s no guarantee that the enhancing response will make the positive risk come to pass, but the conditions make it likely. Consider an organization that will receive a bonus if it completes the project work early. If the business owner crashes the project, the project can be completed early, and the business will receive the bonus. Based on the calculation of the added labor in relation to the size of the bonus, the business owner can elect to add more labor in order to finish faster and receive the bonus for the project completion. While there’s no guarantee that the added labor will definitely finish the project faster, the conditions are set to try to make the opportunity come true.

Enhancing. Enhancing changes the project condition to try to make the opportunity happen. There’s no guarantee that the enhancing response will make the positive risk come to pass, but the conditions make it likely. Consider an organization that will receive a bonus if it completes the project work early. If the business owner crashes the project, the project can be completed early, and the business will receive the bonus. Based on the calculation of the added labor in relation to the size of the bonus, the business owner can elect to add more labor in order to finish faster and receive the bonus for the project completion. While there’s no guarantee that the added labor will definitely finish the project faster, the conditions are set to try to make the opportunity come true.

![]() Sharing. The sharing risk response occurs when an organization shares an opportunity with another entity. For example, a business owner would like to bid on a project, but he doesn’t have enough resources to complete the project work. If he shares the opportunity with a competitor, the two businesses can finish the project work as a joint venture and share the profits. Sharing is also described as teaming agreements and risk-sharing partnerships.

Sharing. The sharing risk response occurs when an organization shares an opportunity with another entity. For example, a business owner would like to bid on a project, but he doesn’t have enough resources to complete the project work. If he shares the opportunity with a competitor, the two businesses can finish the project work as a joint venture and share the profits. Sharing is also described as teaming agreements and risk-sharing partnerships.

![]() Acceptance. Some risks, for both positive and negative risk events, are just accepted based on their conditions, size, probability, and impact. For example, there’s always a chance of force majeure, commonly called acts of God. Force majeure describes earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, and other disasters; these risks are generally accepted, as there’s little you can do to anticipate and mitigate them. You can also accept both positive and negative risk events when the probability and/or impact are so small that the outcome of the risk event is minimal and won’t affect your project.

Acceptance. Some risks, for both positive and negative risk events, are just accepted based on their conditions, size, probability, and impact. For example, there’s always a chance of force majeure, commonly called acts of God. Force majeure describes earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, and other disasters; these risks are generally accepted, as there’s little you can do to anticipate and mitigate them. You can also accept both positive and negative risk events when the probability and/or impact are so small that the outcome of the risk event is minimal and won’t affect your project.

When you and the project team have determined what risk response should be assigned to each risk event, you’ll need to record that response in the risk register. You’ll also need to track the risk events and determine whether the risk response you created is working or whether different actions should be taken. Once the possibility of the event passes, you’ll need to record the outcome of the risk event and document how your risk response worked. This documentation of the risk event can help you not only in the current project, but also in future projects when similar risks are discovered.

Sometimes a risk response can actually create more risk events. A secondary risk describes the condition that arises when a risk response creates an equal or greater risk in the project. For example, in the case of mitigation, the project manager could shift the project work to weekends and evenings, but this change in schedule could cause the project duration to increase, as there are fewer working hours available than there would be if the project work could be done in the daytime.

A residual risk describes smaller risk events that are the result of a risk response. For example, in transference, the dangerous work is transferred to a licensed electrician, but there’s a risk that the electrician won’t do the work properly, will be injured, or will be late completing the assignment. Residual risks are generally accepted, although some may warrant another risk response. In the example of the electrician, mitigation may be implemented through penalties for late completion and a contractual requirement that the electrician must guarantee the work.

A common question among project managers is: “Who does the risk response and when?” Typically, risks are associated with project activities, so it’s the project team member who is closest to the project activities who should be the risk owner. The risk owner is the person who monitors the risk and is authorized to carry out the predetermined risk response. Associated with each risk, you’ll also need to determine a risk trigger. Triggers are metrics or conditions that signal that the event is about to happen and cause the risk owner to implement the prescribed risk response immediately.

When risk owners use the risk trigger, they’ll also need to communicate the conditions to the project manager. The risk owner should alert the project manager to what’s happened, the outcome of the risk event, and how the risk response has worked. Communication in risk management, as in so much of project management, is an essential part of limiting the effect of the risk event on the entire project. You want to contain the risk event and not allow one risk event to contribute to other delays and disruptions in the project.

Monitoring and Controlling Project Risks

Monitoring and controlling project risks happens throughout the project—not just in risk identification and planning. A common theme in monitoring and controlling project risks is to communicate the need to be vigilant in looking for risk events. This means that the project team should feel encouraged to identify risks and report them to the project manager. You’ll need to document an identified risk rather than just nod at the worker and dismiss the event. If you want the members of your project team to be involved in risk identification, you’ll need to take their contributions seriously.

This isn’t hard to do. In your weekly or daily status meetings with your project team, you should always include a discussion of risks that are imminent based on the type of project work currently being done and a quick review of the associated risk responses with the risk owners. Then open the discussion to the members of the project team to share any risk events that they’ve discovered that may need to be analyzed and responded to. If you make it easy for your project team members to share risks and be involved in the project team, they’ll contribute.

From the project manager’s perspective, controlling the project risks involves updating the project management plan and documents. Based on how the work has changed as a result of the identified risks and responses, you’ll need to update all, or some, of these project documents:

![]() Project scope. If you’ve changed the project scope to avoid negative risks or widened the project scope to exploit opportunities, you should reflect that change in the project scope.

Project scope. If you’ve changed the project scope to avoid negative risks or widened the project scope to exploit opportunities, you should reflect that change in the project scope.

![]() WBS. If the project scope changes, you’ll also need to update the WBS so that the final project deliverables are in sync with what the WBS promises to deliver. This will also help with future project planning for similar project work.

WBS. If the project scope changes, you’ll also need to update the WBS so that the final project deliverables are in sync with what the WBS promises to deliver. This will also help with future project planning for similar project work.

![]() Activity lists and project network diagram. Some of your risk responses may cause the project team members to take different actions. These activities will need to be included in the activity list and, when appropriate, the project network diagram. Bear in mind that some of the activities won’t necessarily involve changes in major events, but subtle approaches to how the work is done.

Activity lists and project network diagram. Some of your risk responses may cause the project team members to take different actions. These activities will need to be included in the activity list and, when appropriate, the project network diagram. Bear in mind that some of the activities won’t necessarily involve changes in major events, but subtle approaches to how the work is done.

![]() Cost management plan. Your risk responses may cost your project when you use avoidance, transference, mitigation, and contingency plans. When the cost of risk responses produces financial requirements, these will need to be documented, approved, and updated in the cost management plan. If you elect to use a contingency reserve, this information should also be updated in the cost management plan. Finally, the cost baseline should be updated or annotated to explain the additional costs of the risk events and associated responses.

Cost management plan. Your risk responses may cost your project when you use avoidance, transference, mitigation, and contingency plans. When the cost of risk responses produces financial requirements, these will need to be documented, approved, and updated in the cost management plan. If you elect to use a contingency reserve, this information should also be updated in the cost management plan. Finally, the cost baseline should be updated or annotated to explain the additional costs of the risk events and associated responses.

![]() Schedule management plan. Your risk responses may cause you to complete the project work in an order that’s different from what you originally planned. For example, you may change the relationship of activities, pause the work more frequently for inspections, and reorder the work to avoid bottlenecks. You may also need to update the schedule baseline to reflect the prediction of project completion based on the risks and events in your project.

Schedule management plan. Your risk responses may cause you to complete the project work in an order that’s different from what you originally planned. For example, you may change the relationship of activities, pause the work more frequently for inspections, and reorder the work to avoid bottlenecks. You may also need to update the schedule baseline to reflect the prediction of project completion based on the risks and events in your project.

![]() Procurement management plan. If you have elected to use the transference risk response plan, there may need to be additions to the procurement management plan. Transference includes contracts, so you may have purchase orders, bids, proposals, and other procurement documents to create as well.

Procurement management plan. If you have elected to use the transference risk response plan, there may need to be additions to the procurement management plan. Transference includes contracts, so you may have purchase orders, bids, proposals, and other procurement documents to create as well.

![]() Human resources plan. Some of your risks may require additional and different workers in your project, so you’ll need to update the human resources plan to reflect these requirements. You might also need to update resource calendars to reflect when people are available to work on your project based on how the activities in your project schedule may have shifted.

Human resources plan. Some of your risks may require additional and different workers in your project, so you’ll need to update the human resources plan to reflect these requirements. You might also need to update resource calendars to reflect when people are available to work on your project based on how the activities in your project schedule may have shifted.

![]() Risk management plan and risk register. As new risks are identified and existing risks are responded to, you’ll need to update your risk management plan and risk register to reflect the current activities in the project. You want the risk register to be a history of the risks in your project, the responses you’ve created, and the final outcome of all the risk events.

Risk management plan and risk register. As new risks are identified and existing risks are responded to, you’ll need to update your risk management plan and risk register to reflect the current activities in the project. You want the risk register to be a history of the risks in your project, the responses you’ve created, and the final outcome of all the risk events.

While you may not need to update all of these plans as a result of risk monitoring and controlling, you should be aware that risks can have an impact on all areas of your project. By taking a forward-thinking approach and considering how the risks may affect your project, you’ll be more successful at monitoring, controlling, and communicating risk events.

Seven Questions for Project Risks

Questioning your project details is one of the best methods of identifying and responding to project risks. Here are seven great questions to ask in every project to uncover risks in the project:

1. Have we ever done this before? You should ask this question for every scope requirement and activity in your project. If you’ve never done the work before, there’s a risk that your cost estimates and duration estimates are wrong. You never really know how much a project component will cost and how long it will take until you have done the work. If you have done the work in the past, you should have documentation, or at least recall, of what errors, issues, and risks you experienced then that you want to avoid now.

2. What assumptions are we making? Assumptions are things that you believe to be true, but that you have not proven to be true. Examine your project work for assumptions on how the work will proceed, access to the job site, continuity of project resources, funding, scheduling, availability of equipment and vendors, and other planning components that you haven’t really confirmed as part of your project. Assumptions can become giant risks if they aren’t confirmed. Of course, there are some assumptions that you just have to accept and monitor—such as the assumption that the client won’t cancel the project and go out of business this afternoon.

3. What constraints are enforced on this project? Constraints are limitations: deadlines, budgets, requirements, regulations, and even resources. Constraints, especially unrealistic constraints, are risks. If a customer demands huge requirements, a tight deadline, and a tiny budget, there are bound to be risks lurking in those constraints. Constraints should be examined and the associated risks communicated to the client.

4. What’s the scariest part of this project? If your project involves heavy equipment, construction work, healthcare, or manufacturing, it’s somewhat obvious where the pure risks may be. Other disciplines, however, don’t have many pure risks, but there may still be some scary elements to consider: loss of data, bottlenecked activities, potential delays for customer approvals, reliance on special skill sets or vendors, and even getting paid for the work you’ve completed. The parts of the project that can keep the business owner and the project manager up at night are risks that can’t be ignored.

5. Who’s doing the most work? If you have a superstar on your project team and this person is loaded with the most important activities, is a crucial resource for project success, or is the only person who can complete certain tasks, there’s a risk. Without redundancy of skills, which may not be something that you can readily create, you’ve a risk in your project. If this person gets sick, leaves the company, or wins the lottery, your project can be in instant peril.

6. Which stakeholder is a headache? Some of your project stakeholders can have a high interest in and a high influence over your project work—often the project customer. While you do want the project customer to be involved in the requirements gathering and scope approval processes, you need her to get out of the way so that your project team can work. When you have a customer who is constantly interrupting, you’ll need to manage the customer and your project team to get the project done.

7. What’s the critical path? The critical path is the longest path of activities in the project network diagram, and the activities on it can’t be delayed or the project will be late. Risk-laden activities on the critical path can wreck your whole project. If the risk events come to fruition, your entire project can be delayed because of them. By understanding the risks and mitigating, transferring, or avoiding them, you’ll increase the odds of the success of the project as a whole.