CHAPTER 9

Managing Project Workflow

DURING A PROJECT, it can seem as if everything is happening at once. Once the project is launched, there are lots of project management assignments, demands, constraints, and meetings. Customers want to speak with the project manager about their requirements. Project team members want to receive their assignments and get started. Salespeople want to drop by and chat about their golf game—and about this new project you’re working on. It’s constant e-mails, phone calls, and interruptions from planning the project to closing the project.

The success of a project is the result of the day-to-day management of the activities, communications, issues, and interruptions. While the big picture of project management shows the sequence of activities to get from the start of the project to the close, it’s the steady, persistent actions of the business owner, the project manager, the project team, and the project customer that propel projects to completion. For the project manager, managing the project means ensuring that the work is done accurately, issues are resolved, and communications are maintained. This means identifying and managing the project workflow. This is more than just the ordering of the project events. The project workflow is the management of the activities as they move from one event to the next to get the project work done—the day-today business of executing and controlling the project. It’s the business of getting the project work, managing the project team, communicating with the project team, ensuring that all of the steps required to complete the work properly are done, and handling the documentation of completed tasks, pending tasks, and tasks that are downstream in the project. It’s the linkage between the project management philosophy and the application of real get-it-done project management.

The project workflow lives within the project life cycle, which, as you may recall from Chapter 1, is made up of the various phases of your work. Think of any project you’ve ever completed and you can most likely identify the phases from launch to completion. A good workflow has a steady stream of activities, labor utilization, and progress on the scope objectives.

Exploring Your Project Work

Your business might design software, build decks and patios, or manufacture custom electrical signs for other businesses. Designing software, building decks and patios, and manufacturing signs are examples of projects that companies complete for other entities. Every project has a definite beginning, activities during the execution, and a definite product or end result that represents completion for the project customer. If you’re the business owner, you can probably quickly identify all of the major steps that the project should go through. Can you also, however, identify all of the tiny tasks, the nuances of the work, and the coordinated efforts that it takes for your project team to complete the project?

If you were to do the entire project by yourself, assuming that you could, how long would it take you to plan for what needs to be done, complete all the activities, confirm the quality of the work, communicate with the project customers, and close out the project? The project work that you would complete (that is, the actual activities in the project) is based on the project scope and the work breakdown structure (WBS)—the reflection of what the customer has asked you to create. Once all of the activities in the activity list are completed, then the project’s WBS is completed. Once the WBS is completed, then the project scope is done. The activities that you would complete, however, are unique to your project work.

The linkage, communication, synergy, and management of the people who are doing the activities are what make up the project workflow. The project workflow is the management of the execution of the project and the project team to complete the project activities. The project workflow describes the unique work in your organization and how you, the project manager, will get the project team to do that work correctly, with quality, on time and on budget. The project workflow can follow a high-level flow of activities, or you can create a workflow for each project.

If your company does the same type of projects over and over (for example, creating web sites for customers), your workflow can be standardized within your company. This means that you define the phases of the work, the activities in each phase, and the roles that complete the standard activity. A role is a generic name for the person doing the work, such as graphic designer, Web designer, or Web content writer. Many people in your organization might play more than one role, but the idea is that you’re mapping roles to work. This helps identify who will do what in a project.

Once you have standardized the roles in your organization and in your projects, you can then identify who can serve in what roles. For example, an employee could serve as a graphic designer, a proofreader, and a photographer on any project. When you go to assign activities to users, you can see what role is needed for this standardized work and then choose the person who is available to carry out the work. Some businesses also attach a cost schedule to the role completing the activity. So if a person is serving in more than one role in a project, such as the Web designer role and the photographer role, the work is billed based on the standardized project role, not the employee who is serving in either role.

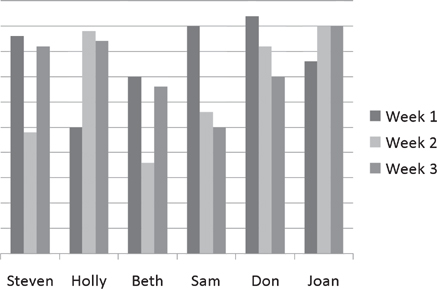

When you use this role-based approach to project management, it’s important to consider resource utilization. Resource utilization is an analysis of how resources are utilized. It allows you to create a resource histogram, as in Figure 9–1, to determine the extent to which resources are used, from those that are used the most down to those that are used the least. Once you’ve identified the utilization of resources, you can balance your resources. You don’t want one person working far too many hours when there are similarly competent employees who could be utilized in the project.

In some cases, you may have more roles than you have employees. When this happen, resource utilization can spike considerably, and this can drive up project labor costs. If you can’t procure additional labor, you may need to level your resource utilization. Resource leveling occurs when you cap the number of hours that an employee can work on the project in any given day, week, or other specified time period.

Figure 9–1. Resource Histogram. Resource histograms help project managers identify the utilization of project resources.

Resource leveling helps to ensure that you’re not overworking the project team members, but it does have a drawback. When you level the resources, your project duration is likely to increase. This is because you’ve limited the number of hours of labor that the project team can complete per day or per week. The actual labor on the project may take the same amount of time, but it will take longer to complete the assigned labor. For example, if a project team member is limited to just 40 hours per week on your project and she used to work 50 per hours per week, the additional 10 hours will be shifted to the following week, and over time this will cause the duration of the project to increase.

Ideally, you’ll have people on your project team who can serve in multiple roles in the project. All project team members are working on a uniform, steady basis, shifting from role to role in the project as needed with a common goal of completing the project work. Far too often, I’ve seen businesses with employees who felt that certain project work either was beneath them or “belonged” to some other team member. It’s the role of the project manager to assess the people who can play various roles in the project and ensure that all project team members are contributing whenever possible to keep the project work moving toward completion.

Identifying the Phases of the Project

A phase is a segment of your project that creates a unique, significant deliverable. The project phases help you break down the work and identify milestones toward progress. The aggregation of all the project phases equates to the project life cycle. Recall that the project life cycle describes the uniqueness of each project; every project that you do has unique attributes that have never been done before. As shown in Figure 9–2, project life cycles are composed of phases.

Consider that for every project, the scope, project requirements, stakeholders, locale for the project work, risks within the project, quality expectations, resources, communications, and even vendors can all be different from those for every other project. No two projects are ever identical, but you may have the same phases within your projects.

Figure 9–2. Project Life Cycle. Project life cycles are composed of phases that represent related work and project progress.

Consider a company that installs awnings for businesses. The awning company follows a simple and logical series of phases in every project it carries out:

![]() The contract is awarded and project materials are procured.

The contract is awarded and project materials are procured.

![]() Work permits and compliance are prepared.

Work permits and compliance are prepared.

![]() The awning structure is built.

The awning structure is built.

![]() The awning is installed to the customer’s satisfaction.

The awning is installed to the customer’s satisfaction.

![]() Payment is made and the project is complete.

Payment is made and the project is complete.

The awning company follows this same routine for every project it does, over and over. You probably have a similar approach to your business, too—there’s a logical step-by-step series of phases that allows your project to go from contract to completion. If you dig a bit deeper, however, there are differences that make each project unique. Let’s go back to the awning business; each stakeholder has different needs and wants for the awning. Each business may require different installation materials; for example, an awning for a glass building may have different requirements from those of an awning for a brick building. Work permits and regulations may differ from county to county and city to city, and the project manager must know the correct procedure to comply with the codes, regulations, and standards. There are probably hundreds more differences that make each awning project unique, but the company uses the same phases to describe the work and activities within that segment of the project.

Now look at your business projects again. Can you see the differences in each project that you complete for others, but similar phases? There will always be unique conditions that differentiate current projects from past projects. If you can find no differences at all, then you’re looking at an operation and not a project. Recall that a project is temporary, whereas operations can go on indefinitely. If you are designing a car, that’s a project; if you’re manufacturing the car, that’s an operation.

The reason why it’s so important to recognize the clear distinction between projects and operations is to acknowledge the need for project management. If every project your company ever did was identical, then you would know exactly what was going to happen next. If every awning installation was identical to the previous ones, there’d be no need to plan, assess risk, or consider materials. But projects are unique, and that’s why they are also complicated. What appears to be a simple project based on simple requirements can evolve into a complex study in logistics, resource coordination, and precise execution and management of labor. Phases help your business break down the work logically and associate activities and resources with it, and they show the progress toward completing the project.

Whatever approach you take to planning and executing the project life cycle, there’s really just one dominant theme: Get the project work done. The project life cycle will last as long as the project phases aren’t completed—the goal of project management is to complete the project life cycle with order, logic, and control. Despite what other project management consultants may say, it’s not about processes and procedures—the point is to get the project done.

Identifying and Managing Cost-Laden Project Phases

Once you’ve identified the phases within your project, you can take a closer look at which phases are cost-laden. Cost-laden phases are those where you’ll have the most expenditures for materials, vendors, labor, and other resources. Determining which phases are the most expensive can help you manage risks and cost overruns. Few projects have a uniform amount of costs throughout the whole project, and most project managers and business owners can identify the most costly phases based on the type of work that the phase contains. It’s important that you identify the cost-laden project phases so that you can anticipate cash flow, monitor the quality of the project work in these phases more closely, and plan intently for cost management. There are some approaches that you can use to plan for cost-laden phases more accurately without getting bogged down in the minutiae of planning before the project work even begins. Your expertise in your discipline and the hands-on knowledge and experience of your project team can help you identify and plan for managing the cost-laden phases. Here are six approaches to documenting and managing cost-laden project phases.

1. Work breakdown structure. Recall that the WBS is a decomposition of the project scope. A good strategy for managing the cost-laden phases of your projects is to change your strategy for WBS creation to reflect the phases of the project rather than just the deliverables of the project scope. In other words, you’ll examine the identifiable phases of the project work and then determine what deliverables are created in each phase. With this approach, you can clearly see which phases are burdened with the most costs and plan more intently for cost control.

2. Cost and schedule estimates. While your project customer may expect a total price and a firm deadline for the project you’re completing, you can create internal cost and schedule estimates for each project phase. This approach can help you predict whether you’ve enough capital to fund each phase, where there may be risks or project delays, and where there may be opportunities for schedule compression and cost savings.

3. Procurement management. Your organization may have a long procurement process for the materials and services that you need in your project, and this can affect rolling-wave planning. If, for instance, your procurement process takes 60 days, you always have to look at least 61 days out to determine your procurement needs so that they mesh with your organization’s procurement processes. If you’re planning only for immediate phases, you may encounter delays when it comes to procurement. In other words, you’ll need to plan for materials that are needed in later phases, even though your focus is on the immediate project work.

4. Human resource management. If your project team members are working on multiple projects at once, you may have to coordinate resource utilization with other project managers. Depending on your phase durations, this can create constraints for your project and for other projects being done by your organization, as you may not know the specific dates when you’ll need your resources on which project. If your project team works on just one project at a time, this isn’t a problem at all, and your project team can focus on planning and completing just this project. If you’re missing resources, however, you’ll either have to pause the project until more resources become available or increase your costs and hire more help.

5. Communication. If you plan your project in phases, you’ll need to think about what needs to be communicated in each phase and whom you’ll communicate with. Because you’re doing lots of iterations of planning, resources and stakeholders need to be available to plan for the specifics of each phase as you start that phase. You’ve already gathered requirements and created the WBS, but you may need access to stakeholders for clarifications, approval of phase expenses, execution approaches, risk management, and communications about the project work that you’re about to start.

6. Scope verification. Scope verification is the process of the customer inspecting the project work that you’ve completed to date and approving that work. If a stakeholder doesn’t approve the work you’ve completed, it’s likely that your project costs will increase because you’ll have to correct whatever the problem may be before you can launch the next phase. You need stakeholder approval of what you’ve done so far in the project, as future project phases often build on what you’ve already completed. Delays resulting from the stakeholder’s inspecting of the project work can also affect your costs, as you may be paying your labor to wait for the stakeholder to approve what you’ve completed before you can move forward.

If your business completes similar projects over and over, like the awning company from earlier in this chapter, you might create a hybrid approach to phase identification and management. In this hybrid approach, you’d have a master project plan that’s adaptable to any of your projects—a basic road map of the typical phases of your project work. This master project plan can be quickly adapted to the current project, with iterations of planning before each phase of the project starts. For this approach to really work, however, your master plan for all similar projects must have enough structure and direction to be usable, but also enough flexibility to be adapted to the conditions in the current project.

PROJECT COACH: The idea of a “master plan” isn’t anything special. It’s the framework I’ve been discussing with you all along. The concept, to be clear, is to create a methodology for doing the project work and for managing the project work. This methodology describes your expectations for how the project will be managed and how the work should be completed.

Managing the Project Team

Despite all your planning efforts, frameworks for project management, and predictable project execution, all projects still come down to this one truth: Projects are completed by people. People aren’t perfect. Your project team members will waste time and materials, say inappropriate things, and be unavailable when you need them the most. The people on your project team will also work hard for you, want the project to succeed, and use their best efforts to complete the project. Managing people is one of the most challenging tasks for any project manager.

PROJECT COACH: I don’t want to criticize your employees, just to highlight what some project managers may experience. If your employees are excellent workers, always do their jobs right the first time, and are eager to learn, hang on to ’em! Too often, I meet employees on project teams who don’t make the connection between their good work and their ongoing employment. Sometimes the project manager or business owner needs to help employees see how their role in the project fits into the success of the company and its ability to make payroll.

Before you can really manage the project team, you need to understand how much authority you have as the project manager. In some companies, the project manager has complete control and authority over the project team, while in others, the project manager is seen more as an expediter than as a manager. If you don’t know what level of authority you have, you need to find out. Talk with your supervisor and determine what you can and cannot do when it comes to managing the project team. You don’t want to overstep your boundaries, but you also don’t want to miss opportunities to manage the project better.

Project managers with limited authority over the project team can still manage the team through referent power. Referent power describes the authority that you have to act on behalf of someone else, such as the business owner. This doesn’t mean that you’re making decisions and disciplining the project team like you’re the new hall monitor. It means that you’re following orders, and you can expect the members of the project team to do what’s requested of them.

There are limitations to how much control you personally have over the project team, but there’s an assumption that the project manager is the person in charge based on who put the project manager in charge. When project team members don’t comply, then the issue is escalated to the appropriate supervisor. Although referent power can be effective, it can also limit the control that the project manager has over the project.

For project managers who have complete, or nearly complete, authority over the project team, there are more options. These project managers are in charge of the project, and the project team is expected to follow their orders. Make no mistake, however; while you may be in charge of the project team, you’re really still part of the project team. The project team will follow your lead, and it’s up to you to involve the team, develop and build the team, and have confidence in the team members’ abilities to plan and do the project work. There’s a fine balance between being imposing and being an authority.

There is a symbiotic relationship between the project manager and the project team: You need to manage the project team, and your team members need to do the work. The project manager’s role involves the logistics of the project life cycle, while the project team’s role is to serve as the experts. In project planning, there’s always an initial assumption that the project team is competent, or through education will become competent, to complete the project work. Communication between the project manager and the project team helps to identify what needs to be done, where skill gaps may exist, and what solutions there may be for completing the project work with quality.

You probably already know the members of your project team—they are the people you work with every day in your business. You know what they are capable of, what their work ethics are, and what they value in their jobs. Some project team members are excited about the project work and want to do a good job for the customer. Other project team members simply see this job as a means to a paycheck. The attitudes of the project team members affect everything that they do. If an individual cannot see the value of the project, her employment, and how her achievements contribute to the project and your customers, it’s up to you to show her.

One of the best methods for managing the project team is recognition. We all want to be recognized when we do something good. We all want to hear that what we’ve done is worthy, we want to feel wanted and appreciated, and we crave genuine praise. Note the genuine part; people know when you’re truly thankful for what they’ve done and when you’re just having a “rah-rah” moment. Genuine recognition and appreciation is one of the most cost-effective methods for improving your projects and garnering trust from your project team.

Managing the project team means that you’re ensuring that the members of that team will recognize the importance of their work and finish the work accurately and on time. The project team members will look to you for their assignments, your expectations of quality, and the ordering of the project events. Throughout the project, you’ll involve the project team members in the planning, coordination, and identification of project work. In a synergistic approach to project management, project ownership will be shared among the project team, the project manager, the business owner, and even the project customer. Ownership of the project equates to pride in the project work, responsibility for the accuracy of the work, and accountability for quality.

Your business environment will affect how project resources are managed. For example, your business may have a crew approach to your projects, where the same group of people works on one project from start to finish. Other businesses may use a specialty approach, where a skilled resource, like an electrician or a carpenter, moves from project to project, contributing just one type of work. Whatever approach you take, you’ll still need some insight on how to coordinate the efforts and utilization of the project team members.

The mechanics of managing the project team are directly related to how you already operate your business. The culture of your business, management’s attitude toward employees, and the type of work you complete for others will all affect how project team members complete their assignments. If you want to change expectations, you’ll have to operate and behave differently, document what the expectations for employees are, and then communicate the change.

The expectations that you probably want to change aren’t the project team’s expectations, but your expectations of what the project team will do. This probably means efficiency, productivity, quality, more focus on the project work, and profitability. As the business owner, you must realize that the project team members don’t see your business the same way you do. To you, your business is your whole life; to your project team members, your business is their job. As a fellow business owner, I can attest that employees, no matter how wonderful they are as people, will never love your business the way you do. Employees aren’t as emotionally tied to the success of your business, and they often won’t work as diligently as you will.

This doesn’t mean that employees are evil. It just means that what motivates you, the business owner, doesn’t necessarily motivate your employee. As the business owner or project manager, you need to determine what motivates your employees to excel. If you understand what excites the members of your project team and what things they want in their careers and in their lives, you can discover opportunities to promote performance. Knowing your project team members and what their desires are allows you to help them excel in their lives and helps you grow your business. It’s a win-win-win scenario for your business, the project team members, and your project customers.

Coordinating Efforts

The coordination of the project team is both a project planning activity and a monitoring and controlling activity. In project planning, you’ve identified the project activities and the ordering of the project events. For each project activity, you’ll need to assign at least one resource to the activity to get the work done. When you assign workers to activities, there’s an expectation concerning how long the activity will take and the efficiency and accuracy of the worker, and an assumption that the work will finish on time to allow other activities to proceed. When these assumptions and expectations prove false, there’s a wrinkle throughout your project execution.

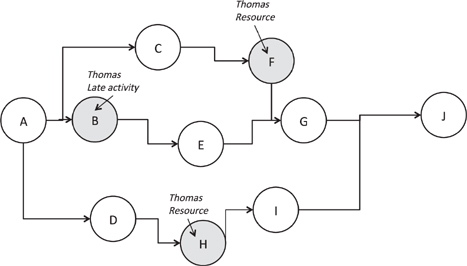

As shown in Figure 9–3, when there’s a delay on one activity, downstream activities are also delayed. In addition, note that Thomas is assigned to Activity B, which is the late activity in the example. Not only do all of the predecessors of Activity B get delayed, but so will Activities F and H because Thomas is a resource for these events. Even though Activities F and H aren’t direct predecessors of Activity B, Thomas can’t start working on the other events as quickly as he otherwise would because he’s still completing Activity B.

When situations like this arise, the project manager has to rely on logic. As in a chess game, the project manager examines all the possible moves and outcomes and makes a decision. For example, the project manager may determine that other resources can be added to Activity B to finish the task faster, or that another resource can replace Thomas on Activity B, allowing Thomas to move on to Activities F and H. The project manager might also see what resources are available for Activities C, F, D, and H and shift the order of the activities. Or the project manager might realize that Activities F and H aren’t on the critical path, so a small delay on these activities won’t affect the project end date.

Figure 9–3. Issue Identification. Single, apparently small problems can cause multiple problems in a project. Solutions require both monitoring and controlling and planning.

There are countless solutions to just this one issue, but most projects have several problems, risks, and situations that all demand the project manager’s attention. Experience teaches the project manager how to differentiate and prioritize the petty and the important. Here is a quick guide to managing any issue in any project:

![]() What’s the real problem? Make sure you’re dealing with the causal factors of a problem and not just an effect of the problem. Late completion of a task is a problem that will affect your project, but if the cause of the late completion is that the project team members can’t get access to the job site for three hours every day, the problem will continue.

What’s the real problem? Make sure you’re dealing with the causal factors of a problem and not just an effect of the problem. Late completion of a task is a problem that will affect your project, but if the cause of the late completion is that the project team members can’t get access to the job site for three hours every day, the problem will continue.

![]() Is there an obvious solution? Don’t overthink the real problem. Most of the time, the most obvious solution is the correct one. This doesn’t mean that you need an instant answer, but you need quick answers. All problems and issues need to be pondered for at least a moment to see what ramifications the obvious solution will have. The longer you sit on a decision, the worse the situation will become.

Is there an obvious solution? Don’t overthink the real problem. Most of the time, the most obvious solution is the correct one. This doesn’t mean that you need an instant answer, but you need quick answers. All problems and issues need to be pondered for at least a moment to see what ramifications the obvious solution will have. The longer you sit on a decision, the worse the situation will become.

![]() How does this problem affect the project outcome? Examine the issue and determine how it really affects the project. Find out what the problem does to your project costs, schedule, and quality, and determine whether new risks are being introduced because of the problem. Some problems just don’t matter and can be quickly solved or accepted. Other problems can mean significant changes in your project and will need planning activities to manage.

How does this problem affect the project outcome? Examine the issue and determine how it really affects the project. Find out what the problem does to your project costs, schedule, and quality, and determine whether new risks are being introduced because of the problem. Some problems just don’t matter and can be quickly solved or accepted. Other problems can mean significant changes in your project and will need planning activities to manage.

![]() Who needs to know? You don’t need to announce every problem to your business and your clients, but problems often need to be communicated. The cause of the problem needs to be documented and discussed with the correct stakeholders. Your authority over the project will guide you on this step. Some business owners will demand that you report every hiccup, while other business owners will have hired you, the project manager, to manage the problems. Understand the problem, determine who needs to know, and then act accordingly.

Who needs to know? You don’t need to announce every problem to your business and your clients, but problems often need to be communicated. The cause of the problem needs to be documented and discussed with the correct stakeholders. Your authority over the project will guide you on this step. Some business owners will demand that you report every hiccup, while other business owners will have hired you, the project manager, to manage the problems. Understand the problem, determine who needs to know, and then act accordingly.

![]() Is this going to happen again? If the problem could happen again, you’ve identified a risk. Risks can be responded to, anticipated, and prevented. If the problem is likely to occur again, you’ll need to investigate what preventive actions you can take to avoid the risk event; that means project planning, updating project events, and coaching your project team to do the work properly.

Is this going to happen again? If the problem could happen again, you’ve identified a risk. Risks can be responded to, anticipated, and prevented. If the problem is likely to occur again, you’ll need to investigate what preventive actions you can take to avoid the risk event; that means project planning, updating project events, and coaching your project team to do the work properly.

Every decision that you make affects the project team. A good project manager involves the project team in the decisions, asks for its input, and has confidence in the team members to do the work properly. Decisions need to be communicated to the project team members, as they’ll want to know what’s expected of them in your project. Project team members want to know what you want them to do, when they’re supposed to do it, and what the predicted outcome of the task will be. As in so much of project management, communication is the key to getting the project team members to carry out their assignments as expected.

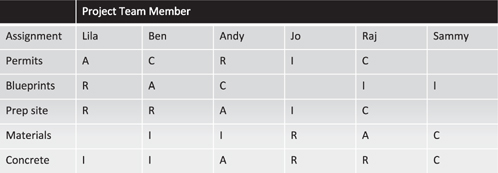

One tool that you can use to coordinate the efforts of the project team quickly is a RACI chart, as shown in Figure 9–4. A RACI chart is a matrix that uses the concepts of Responsible, Accountable, Consult, and Informed to describe who does what in the project. The first column lists all the project activities, and across the columns are the names of the project team members. At the intersection of an activity and a project team member, you’ll use one of the elements of RACI for that project team member. At a glance, you and the project team members can see what role everyone plays in the project and in each upcoming assignment.

A RACI chart is a type of responsibility assignment matrix (RAM), which is just a table to determine who does what in the project. RAMs, like RACI charts, identify roles and responsibilities in the project, but the difference is that a RAM can use any legend you create for the activities. For example, you might use a legend of Participant, Responsible, Inspector, and Accountable in your RAM. Either type of chart helps you ensure that every activity in the project has someone assigned to the project work.

Figure 9–4. RACI Chart. RACI charts identify the involvement of project team members in each project assignment.

RACI - Responsible, Accountable, Consult, Inform

Coordinating the project work also means that you need to know what’s happening in the day-to-day accomplishment of project assignments. The project team members must report when their work is done, the actual duration of the project work, and the outcome of the project assignment. The project manager can then determine whether the completed work needs to be inspected for quality or whether he should allow the project to continue—and sometimes both.

Five Techniques for Project Workflow

Project workflows are the multiple paths that are influenced by the business owner, the project manager, the project team, the project customers, and conditions within the project. Workflows, like projects, are unique to each project. What has worked in the past won’t always work the same way in the future. What you have learned from previous workflows, however, can always help you to manage the current project more successfully. Here are five techniques that you can apply to your project life cycles and the project management life cycle to improve your workflows:

1. Define a successful workflow. How do you know when a project is operating smoothly? Is it only when there isn’t a flood of issues, complaints, and problems in the project? Or can you tell that a project is operating smoothly when the project team is completing the work with little or no interruption? Your company’s idea of a successful workflow may differ from your competition’s. Identify what makes a successful workflow and then you’ll have goals to achieve. It’s easier to hit your target if you know what it is.

2. Do whatever it takes. Some project managers and business owners have an attitude that they are above some of the activities in the project work. If you want your project, and to some extent your business, to be successful, you’ll do whatever it takes to get the project done. This can mean investing long nights and weekends in the project, doing menial project work to free up valuable resources, and patiently teaching your project team members how you want the work completed.

3. Communicate expectations. Project team members can live up to your expectations if they know what’s expected of them. It’s not fair or reasonable to set high levels of expectations for your team and then not communicate those expectations. You’ll also need to provide avenues that will enable the members of the project team to reach the expectations. You can’t demand zero mistakes in the project work, but also rush the project team to complete its work as quickly as possible.

4. Little changes add up. It’s usually easier for the project team to incorporate little changes over time than to incorporate immediate, broad, sweeping changes. Kaizen is a Japanese word that describes tiny changes toward improvement. By doing many tiny, incremental steps, the goal is eventually realized. In your projects, you can use kaizen to implement workflow requirements and procedures over time.

5. Take charge. If you’re the project manager, you need to be in charge of the project. Taking charge means that you’ll prioritize the project work, communicate what’s going to happen next in the project, and be in control of the workflow. Taking charge also means that you’re leading the project team, instilling confidence in your stakeholders, and being responsible for the project’s successes or failures.