Hour 16. Using CSS to Do More with Lists

In Hour 5, you were introduced to three types of HTML lists, and in Hour 14 you learned about margins, padding, and alignment of elements. In this hour, you will learn of how margins, padding, and alignment styles can be applied to different types of HTML lists, helping you produce some powerful design elements purely in HTML and CSS.

Specifically, you will learn how to modify the appearance of list elements—beyond the use of the list-style-type property that you learned in Hour 5—and how to use a CSS-styled list to replace the client-side image maps you learned about in Hour 11. You will put into practice many of the CSS styles you’ve learned thus far, and the knowledge you will gain in this hour will lead directly into the projects you will tackle in Hour 17, “Using CSS to Design Navigation.”

HTML List Refresher

As you learned in Hour 5, there are three basic types of HTML lists. Each presents content in a slightly different way based on its type and the context:

• The ordered list is an indented list that displays numbers or letters before each list item. The ordered list is surrounded by <ol> and </ol> tags and list items are enclosed in the <li></li> tag pair. This list type is often used to display numbered steps or levels of content.

• The unordered list is an indented list that displays a bullet or other symbol before each list item. The unordered list is surrounded by <ul> and </ul> tags and list items are enclosed in the <li></li> tag pair. This list type is often used to provide a visual cue that brief, yet specific, bits of information will follow.

• A definition list is often used to display terms and their meanings, thereby providing information hierarchy within the context of the list itself—much like the ordered list but without the numbering. The definition list is surrounded by <dl> and </dl> tags with <dt> and </dt> tags enclosing the term and <dd> and </dd> tags enclosing the definitions.

When the content warrants it, you can nest your ordered and unordered — or place lists within other lists. Nested lists produce a content hierarchy, so reserve their use for when your content actually has a hierarchy you wish to display (such as content outlines or tables of content). Or, as you will learn in Hour 17, you can use nested lists when your site navigation contains sub-navigational elements.

How the CSS Box Model Affects Lists

Specific list-related styles include list-style-image (for placement of an image as a list-item marker), list-style-position (indicating where to place the list-item marker), and list-style-type (the type of list-item marker itself). But while these styles control the structure of the list and list items, you can use margin, padding, color, and background-color styles to achieve even more specific displays with your lists.

Note

Some older browsers handle margins and padding differently, especially around lists and list items. However, at the time of writing, the HTML and CSS in this and other chapters in this book are displayed identically in current versions of the major web browsers (Apple Safari, Google Chrome, Microsoft Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera). Of course, you should still review your web content in all browsers before you publish it online, but the need for “hacking” style sheets to accommodate the rendering idiosyncrasies of browsers is fading away.

In Hour 14, you learned that every element has some padding between the content and the border of the element; you also learned there is a margin between the border of the element and any other content. This is true for lists, and when you are styling lists, you must remember that a “list” is actually made up of two elements: the parent list element type (<ul> or <ol>) and the individual list items themselves. Each of these elements has margins and padding that can be affected by a style sheet.

The examples in this hour show you how different CSS styles affect the visual display of HTML lists and list items. With these basic differences in mind, you will be able to fully control lists and, as you will practice in Hour 17, you will be able to use lists to achieve advanced visual effects within site navigation.

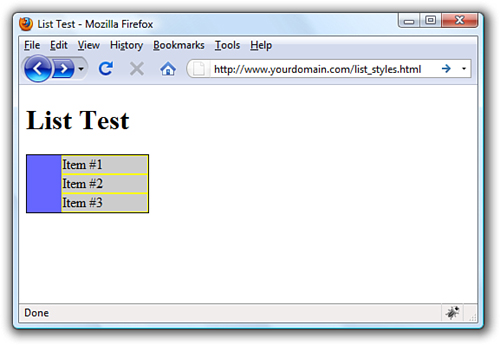

Listing 16.1 creates a basic list containing three items. In this listing, the unordered list itself (the <ul>) is given a blue background, a black border, and a specific width of 100 pixels, as shown in Figure 16.1. The list items (the individual <li>) have a grey background and a yellow border. The list item text and indicators (the bullet) are black.

Listing 16.1 Creating a Basic List with Color and Border Styles

Figure 16.1 Styling the list and list items with colors and borders.

As shown in Figure 16.1, the <ul> creates a box in which the individual list items are placed. In this example, the entirety of the box has a blue background. But also note that the individual list items—in this example, they use a grey background and a yellow border—do not extend to the left edge of the box created by the <ul>.

Note

You can test the default padding-left value as displayed by different browsers by creating a simple test file such as that shown in Listing 16.1, then adding padding-left: 40px; to the declaration for the ul selector in the style sheet. If you reload the page and the display does not change, then you know that your test browser uses 40 pixels as a default value for padding-left.

This is because browsers automatically add a certain amount of padding to the left side of the <ul>. Browsers don’t add padding to the margin, as that would appear around the outside of the box. They add padding inside the box and only on the left side. That padding value is approximately 40 pixels.

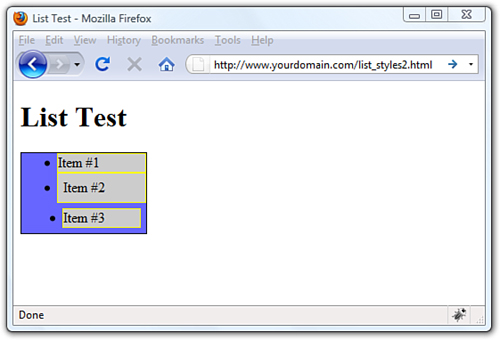

The default left-side padding value remains the same regardless of the type of list. If you add the following line to the style sheet, creating a list with no item indicators, you will find the padding remains the same (see Figure 16.2):

![]()

Figure 16.2 The default left-side padding remains the same with or without list item indicators.

When you are creating a page layout that includes lists of any type, play around with padding to place the items “just so” on the page. Similarly, just because there is no default margin associated with lists doesn’t mean you can’t assign some to the display; adding margin values to the declaration for the ul selector will provide additional layout control.

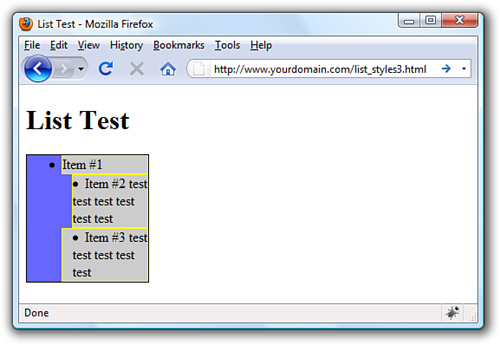

But remember, so far we’ve worked with only the list definition itself; we haven’t worked with the application of styles to the individual list items. In Figures 16.1 and 16.2, the grey background and yellow border of the list item shows no default padding or margin. Figure 16.3 shows the different effects created by applying padding or margin values to list items rather than the overall list “box” itself.

Figure 16.3 Different values affect the padding and margins on list items.

The first list item is the base item with no padding or margin applied to it. However, the second list item uses style="padding: 6px;" and you can see the six pixels of padding on all sides (between the content and the yellow border surrounding the element). Note that the placement of the bullet remains the same as the first list item. The third list item uses style="margin: 6px;" to apply six pixels of margin around the list item; this margin allows the blue background of the <ul> to show through.

Placing List Item Indicators

All this talk of margins and padding raises another issue: the control of list item indicators (when used) and how text should wrap around them (or not). The default value of the list-style-position property is “outside”—this placement means the bullets, numbers, or other indicators are kept to the left of the text, outside of the box created by the <li></li> tag pair. When text wraps within the list item, it wraps within that box and remains flush left with the left border of element.

But when the value of list-style-position is “inside,” the indicators are inside the box created by the <li></li> tag pair. Not only are the list item indicators then indented further (they essentially become part of the text), the text wraps beneath each item indicator.

An example of both outside and inside list-style-positions is shown in Figure 16.4. The only changes between Listing 16.1 and the code used to produce the example shown in Figure 16.4 (not including the filler text added to “Item #2” and “Item #3”) is that the second list item contains style="list-style-position: outside;" and the third list item contains style="list-style-position: inside;".

Figure 16.4 The difference between outside and inside values for list-style-position.

The additional filler text used for the second list item shows how the text wraps when the width of the list is defined as a value that is too narrow to display all on one line. The same result would have been achieved without using style="list-style-position: outside;" because that is the default value of list-style-position without any explicit statement in the code.

However, you can clearly see the difference when the “inside” position is used. In the third list item, the bullet and the text are both within the grey area bordered by yellow—the list item itself. Margins and padding affect list items differently when the value of list-style-position is inside (see Figure 16.5).

Figure 16.5 Margin and padding changes the display of items using the inside list-style-position.

In Figure 16.5, both the second and third list items have a list-style-position value of inside. However, the second list item has a margin-left value of 12 pixels and the third list item has a padding-left value of 12 pixels. While both content blocks (list indicator plus the text) show text wrapped around the bullet, and the placement of these blocks within the grey area defining the list item is the same, the affected area is the list item within the list itself.

As you would expect, the list item with the margin-left value of 12 pixels displays 12 pixels of red showing through the transparent margin surrounding the list item. Similarly, the list item with the padding-left value of 12 pixels displays 12 pixels of grey background (of the list item) before the content begins. Padding is within the element; margin is outside the element.

By understanding the way margins and padding affect both list items and the list in which they appear, be able to create navigation elements in your web site that are pure CSS and do not rely on external images. In Hour 17, you will learn how to create both vertical and horizontal navigation menus as well as menu drop-downs.

Creating Image Maps with List Items and CSS

In Hour 11, you learned how to create client-side image maps using the <map/> tag in HTML. Image maps allow you to define an area of an image and assign a link to that area (rather than having to slice an image into pieces, apply links to individual pieces, and stitch the image back together in HTML). However, you can also create an image map purely out of valid XHTML and CSS.

Note

For links to several tutorials geared toward creating XHTML and CSS image maps, visit http://designreviver.com/tutorials/css-image-map-techniques-and-tutorials/. The levels of interactivity in these tutorials differ, and some might introduce client-side coding outside of the scope of this book, but the explanations are thorough.

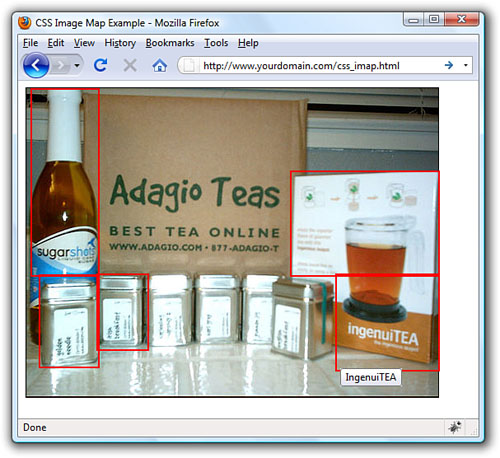

The code in Listing 16.2 produces an image map similar to the one shown in Figure 16.6. (The code in Listing 16.2 does not produce the red borders shown in the figure. The borders were added to the figure to highlight the defined areas.) When the code is rendered in a web browser, it simply looks like a web page with an image placed in it. The actions happen when your mouse hovers over a “hot” area.

Listing 16.2 Creating an Image Map Using CSS

Figure 16.6 CSS allows you to define hotspots in an image map.

As shown in Listing 16.2, the style sheet has quite a few entries but the actual HTML is quite short. List items are used to create five distinct clickable areas; those “areas” are list items given a specific height and width and placed over an image that sits in the background. If the image is removed from the background of the <div> that surrounds the list, the list items still exist and are still clickable.

Let’s walk through the style sheet so that you understand the pieces that make up this XHTML and CSS image map, which is—at its most basic level—just a list of links.

The list of links is enclosed in a <div> named "theImg". In the style sheet, this <div> is defined as block element that is 500 pixels wide, 375 pixels high, and with a 1 pixel solid black border. The background of this element is an image named tea_shipment.jpg that is placed in one position and does not repeat. The next bit of HTML that you see is the beginning of the unordered list (<ul>). In the style sheet, this unordered list is given margin and padding values of zero pixels all around and a list-style of none—list items will not be preceded by any icon.

The list item text itself never appears to the user because of this trick in the style sheet entry for all <a> tags within the <div>:

![]()

By indenting the text negative 1000 ems, you can be assured that the text will never appear. It does exist, but it exists in a non-viewable area 1000 ems to the left of the browser window. In other words, if you raise your left hand and place it to the side of your computer monitor, text-indent: -1000em places the text somewhere to the left of your pinky finger. But that’s what we want because we don’t need to see the text link. We just need an area to be defined as a link so that the user’s cursor will change as it does when rolling over any link in a web site.

When the user’s cursor hovers over a list item containing a link, that list item shows a one-pixel border that is solid white, thanks to this entry in the style sheet:

![]()

The list items themselves are then defined and placed in specific positions based on the areas of the image that are supposed to be the clickable areas. For example, the list item with the "ss" id, for "Sugarshots"—the name of the item shown in the figure—has its top-left corner placed zero pixels from the top of the <div> and five pixels in from the left edge of the <div>. This list item is 80 pixels wide and 225 pixels high. Similar style declarations are made for the "#gn", "#ib", "#iTEA1", and "#iTEA2" list items, such that the linked areas associated with those ids appear in certain positions relative to the image.

Summary

This hour began with examples of how lists and list elements are affected by padding and margin styles. You first learned about the default padding associated with lists and how to control that padding. Next you learned how to modify padding and margin values and how to place the list item indicator either inside the list item or outside it, so you could begin to think about how styles and lists can affect your overall site design. Finally, you learned how to leverage lists and list elements to create a pure XHTML and CSS image map, thus reducing the need for slicing-up linked images or using the <map/> tag.

All of the examples in this hour were geared toward having you “think outside the (list) box,” if you will, so that in the next hour you can embrace the use of unordered lists to produce horizontal or vertical navigation within your web site.

Q&A

Q There are an awful lot of web pages that talk about the “Box Model hack” regarding margins and padding, especially around lists and list elements. Are you sure I don’t have to use a hack?

A At the beginning of this hour, you learned that the HTML and CSS in this hour (and others) all look the same in the current versions of the major web browsers. This is the product of several years of web developers having to do code hacks and other tricks before modern browsers began handling things according to CSS specifications rather than their own idiosyncrasies. Additionally, there is a growing movement to rid Internet users of the very old web browsers that necessitated most of these hacks in the first place. So, while I wouldn’t necessarily advise you to design only for the current versions of the major web browsers, I also wouldn’t recommend that you spend a ton of time implementing hacks for the older versions of browsers—which are used by less than five percent of the Internet population. You should continue to write solid code that validates and adheres to design principles, test your pages in a suite of browsers that best reflects your audience, and release your site to the world.

Q The CSS Image Map seems like a lot of work. Is the <map/> tag so bad?

A The <map/> tag isn’t at all bad, and is valid in both XHTML and HTML 5. The determination of coordinates used in client-side image maps can be difficult, however, especially without graphics software or software intended for the creation of client-side image maps. The CSS version gives you more options for defining and displaying clickable areas, only one of which you’ve seen here.

Workshop

The workshop contains quiz questions and activities to help you solidify your understanding of the material covered. Try to answer all questions before looking at the “Answers” section that follows.

Quiz

1. What is the difference between the “inside” and “outside” list-style-position values? Which is the default value?

2. Does a list-style with a value of “none” still produce a structured list, either ordered or unordered?

3. What HTML code creates a list item that is 350 pixels wide, 100 pixels high, with a green background, a two-pixel dashed black border, and the list item indicator placed inside the container?

Answers

1. The list-style-position value of “inside” places the list item indicator inside the block created by the list item. A value of “outside” places the list item indicator outside the block. When “inside,” content wraps beneath the list item indicator. The default value is “outside.”

2. Yes. The only difference is that no list item indicator is present before the content within the list item.

Exercises

• Find an image and try your hand at mapping areas using the technique shown in this hour. Select an image that has areas you could use “hot spots” or clickable areas leading to other web pages on your site or to someone else’s site. Then create the HTML and CSS to define the clickable areas and the URLs to which they should lead.

• In preparation for using lists as navigational elements in the next hour, think about your site structure and sketch out some top-level navigation as well as some secondary navigation links in those main sections. Think about whether your omnipresent navigational method will be horizontal or vertical navigation.