CONTENTS

Key enablers to the art of preparing

Mindful practices: the power of empowerment

The impact of preparing on relationships

Mindful practices: establishing long-term commitment

Mindful practices: winning hearts and minds

The mindful organism of a project requires a state of preparedness and readiness to contain adversity. As part of this, project managers need to be innovative in producing novel responses to emerging epistemic uncertainty which, should uncertainty emerge, they can employ to minimise the impacts on the project.

The lure of the fail-safe

Planning for adversity often relies on traditional, probabilistic risk management. The risk management process involves identifying aleatoric uncertainty (in the form of risks) that might threaten the delivery of the project and finding ways to reduce or neutralise them. Typically, a process will be enacted whereby risks are identified and strategies put into place to tackle them. These strategies often include finding ways to eliminate the sources of risk, possibly transferring ownership of the problem to someone else (perhaps a supplier) and reducing the possible impact of remaining risks to what might be regarded as acceptable (by putting in place contingency plans). In principle, this is fine; the project can proceed, safe in the knowledge that risk is contained. The key problem with this is that the whole process of preparation and readiness is based on those risks that can be identified. We engage with the project with confidence born of the knowledge that we have conducted a thorough risk management analysis, yet ignorant of the potentially ruinous areas of epistemic uncertainty that we still face – everything beyond the risk horizon. While we have prepared for what we know and understand, we are still vulnerable to the unknown and unexpected.

Fixation on planning

Planning provides clear benefits to project management, but planning can also be detrimental if not implemented properly. We may become so fixated on planning for every eventuality in detail that it ‘anchors’ our expectation to such an extent that it inhibits and stifles creativity and initiative to deviate from a plan and adapt. A detailed plan might be perceived as a ‘good’ plan, but in essence, turns assumptions and estimates into rigidity in mind and action.

Perhaps the most well-known, consistently demonstrated and common cognitive bias found among people, both in everyday life and in organisational life, is the planning fallacy. First identified by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), it has since been the subject of research and investigation (Buehler et al. 1994). The implications, although profound, are still found in all aspects of organisational activity; especially projects (Kutsch et al. 2011).

The planning fallacy mindset refers to the tendency of people to underestimate the time, cost and risk involved in any undertaking, even when they have prior knowledge of exactly what the task will entail (Klayman and Schoemaker 1993). Plans are over-optimistic and often unreasonably mirror the best-case scenario. More specifically, it was found (Kahneman and Tversky 1979) that people predict outcomes of undertakings based only on specific, singular elements of a plan, ignoring distributional data, sometimes called the insider–outsider view. The planning fallacy can be seen in all sorts of everyday experiences such as estimating the time it will take to make a long journey, the time it will take to complete your tax return and so on.

The effects of the planning fallacy tend to be cumulative. The more steps that are involved in planning a task, the more problematic the effect is likely to be. This is because of several reasons. People rarely consider the risk involved in activities or, if they do consider risk, they tend to downplay it (Kutsch et al. 2014). Another reason is that the process of planning involves a future-orientation, which means people are unlikely to consider their past experiences. Even where people do consider the distribution of past experiences, they actively process the information to reduce the pertinence of that information on the planning for the current task (Buehler et al. 1994).

Erosion of effectiveness

Many possible uncertainties will, of course, never materialise. They may never have existed in the first place, or they were mitigated through management. The distinction between ‘good’ deterministic and probabilistic control and good luck can sometimes be a fine line, though. The preoccupation with control may lead to the temptation to ‘cut corners’ and reduce the extent of preparations towards the epistemic uncertainty. We dutifully consider the list for a new project, and some risks begin to be relegated. Perhaps these issues have never been experienced in the past, or have not occurred for a long time; maybe we have been involved with a string of successful projects and begin to think that our projects are less uncertain than we first imagined. Clearly, our team is particularly talented – those problems are more likely to affect others, not us. As a result, the nagging doubts fade, confidence grows, in an illusion of certainty. At the same time, pressure on resources encourages us to seek opportunities for greater efficiency. Perhaps one way of freeing up resources, thereby taking the pressure off the budget, is to remove some of the activities directed at protecting the project from these uncertainties that are thought never to have materialised.

Optimism bias

Project managers tend to be optimistic. The undertaking of projects demands optimism that difficult and complex objectives can be achieved. Previously we argued that we tend to underestimate the extent of the adversity to which we are exposed. Making matters worse, we may also believe that our preparation covers more possible adversity than it does. As a result, we overestimate our preparatory state. In many respects, adopting a state of optimism is necessary for us. We need to be confident that we can achieve our goals. However, without some reality check, there is a danger that we become overly optimistic about our ability to reach the project’s goals, and thus are overconfident in our abilities to address epistemic uncertainty.

Sometimes called the ‘contagion effect’, the bandwagon effect is a well-known phenomenon of the general and prevailing opinion impinging upon individuals. What this means is that people tend to take on a view or adopt a behaviour simply because they observe other people doing so. The more people who adopt a behaviour or opinion, the more likely it is that other people will join them (Mutz 1998).

There are many examples of the bandwagon effect that can be observed in everyday life, from fashion trends to musical tastes and from political affiliations to dietary tastes. One more recent example is the take up of different social networking platforms. There are many available, but only a few have risen to prominence.

While the bandwagon effect can be observed, understanding it has been more difficult. Some factors that have been identified are an irrational fear of social isolation and people’s desire to be on the winning side. More recently, it has been found that people tend to develop a ‘consensus heuristic’, taking the majority opinion as the intelligent choice where they lack the expertise to decide for themselves (Mutz 1998). Groupthink is another important factor where there is tremendous pressure to conform to what everyone else is doing. The bandwagon effect also speaks to people’s desire to belong to a group, which pressures them to the norms and attitudes of the majority.

There are some severe downsides to the bandwagon effect in society at large and also in organisational life. In society, for example, the growing anti-vaccination phenomenon has, in part, been attributed to this cognitive bias (Hershey et al. 1994). In organisations, the bandwagon effect has been identified as a factor in entry strategies into new markets as well as the adoption of other strategic and operational management ‘fads’ such as Lean Production techniques and Total Quality management (TQM) (Jung and Lee 2016).

Running on autopilot

The ‘language’ of project management consists to a great extent of written action plans, instructions, and procedures. Articulation is in the form of documents, booklets, and manuals that can sit on a shelf unread and be forgotten about or, increasingly commonly, it resides in databases and on project management information systems. Uncertainty becomes inchoate and opaque. Even if we can be persuaded to engage with the documentation and project management IT systems, they are often perceived as an abstraction from the day-to-day lived reality. Learning, and hence preparation, is arid and lacking in immediacy. There is no sense of getting ‘close’ to plans. Whereas the execution of plans – the act of containing adversity – stretches our senses and emotions, planning is ‘dry’ and can be mostly confined to documenting. Planning in all its abstraction does not form an adequate platform for ‘really’ understanding adversity; of what we know and do not know about the future state of a project.

Automating a response

Project management rigidity is very useful when it comes to imposing stability and discipline. This is often based on an analysis that considers past experiences and documents to be the mandated strategy (usually from recent successes, so this does have some justifiable rationale). The emphasis is on recognised structures, top-down governance and control systems, and prescribed processes and methods. This control is valuable as it ensures that people in the project know what they are doing and do not expose the project to unnecessary adversity through unexpected actions. In this way, the project can indeed be considered as prepared. However, rigidity itself has the potential to become a risk. Backwards-looking procedures and processes stifle the flexibility needed to engage with the novelty and surprise that come with uncertainty. A pragmatic balance is hard to define and articulate within the project.

Automation bias is a cognitive bias that has emerged relatively recently. It is prevalent where automated decision-making tools operate in conjunction with human decision-making. It involves the over-reliance on automated decision support systems that can be found in many different environments (Raja Parasuraman and Manzey 2010). The bias lies in trust in the automated system and the complacency among people that emerges as they rely less on their own or others’ inputs.

The kind of highly automated systems that might give rise to automation bias range from complex systems like nuclear control centres and aircraft cockpits to more prosaic examples such as spellcheckers or word processing software. In all cases, people are found to cede some or all their human agency to the automated decision-making tools. Another example is the autopilots for the new breed of electric vehicles (such as Tesla). The autopilot does not truly automate driving but, instead, automates some functions of driving. However, there have been some high profile incidents of people relying on the autopilot functions of these vehicles with, sometimes, catastrophic outcomes.

The problem in organisations is that operatives have been found to be very poor at recognising when the automatic systems they are relying upon have failed and that human intervention is required (Parasuraman et al. 2009). To illustrate this point, there are numerous examples of mistakes and errors being made by, for example, aircraft pilots who rely too heavily on their autopilots.

Technology developers have tried to overcome the problem by giving human operators the final decision in many systems but, even then, it has been found that those operators blithely trust the decision made by the automated system and accept it without checking. In organisations, the effect is to rob people of their critical input into decision-making.

A silo mentality

To ‘defend’ a project from adversity, the tendency is often to increase the number of layers within it, both vertically and horizontally. Horizontally, we create silos of specialism and expertise; vertically, we add layers to a hierarchy to have dense, multi-layered defence mechanisms in place. What we tend to forget is that, by doing this, we can add complexity, and hence uncertainty, to the project, and make the project more cumbersome. More silos imply more effort to overcome the inherent barriers, be they defined by specialism, ego, or status. Silos create barriers to communication, in terms of how quickly information gets communicated and in its resultant interpretation by different specialisms. Similarly, specialist groups often form intense, cohesive bonds, which encourage them to protect their own unit from uncertainty, even if this is to the detriment of the overall project. It can create a dangerous ‘us and them’ attitude.

Key enablers to the art of preparing

Rigidity and inflexibility, built-in through too detailed planning, are situations we with which we are frequently confronted. This raises some difficult questions. For example, how much planning is actually ‘enough’? When does (over)planning become a risk in itself? Although there are no clear answers to these questions, there are some enablers that can be considered in the planning stages to prepare a project for the adversity that comes with, in particular, uncertainty. Preparing for uncertainty is a leap of faith. We must believe that our preparation has some positive effect on containing adversity from destabilising our project. In advance of uncertainty and complexity materialising, there will not be any proof of its effectiveness. Belief and confidence in the effectiveness of your preparation and readiness are therefore paramount.

A wide response repository

One crucial aspect necessary in preparing for epistemic uncertainty is the creation of social redundancy: establishing a wide set of skills and capabilities across the project team that can be focused on any problem that might arise. This involves project staff and workers having to have not only the pertinent skills but also ideally the ability to slot into each other’s roles where necessary. This allows the team to develop a comprehensive and active response repository to deploy against any given situation. This is important as, to contain the effects of uncertainty as it emerges, staff need to act quickly and with focus. Cross-training in a range of skills, beyond individuals’ ‘core’ functions, helps create a built-in redundancy within projects. This excess of skills in the project team may not always be necessary or required (and indeed, it is likely to be a financial expense and possibly a drain on efficiency) until an unanticipated problem arises. It is at this time that the skills become crucial and the value of this investment becomes apparent.

Empowerment

As shown in Figure 5.1, the more ‘traditional’ approach to problem-solving is that decision power migrates to different sources of expertise – often defined by hierarchical position or status – until the particular problem is resolved. As a consequence, the nature of the difficulty may need to be conveyed and translated, often resulting in the loss of time and meaning on the way.

Figure 5.1 Empowerment beyond specialism

An alternative approach is to ensure that the people close to the problem are equipped to deal with it. To do this, they need an extensive response repository to deal with any given problem, be it commercial, legal or technical. Escalations are only necessary when the boundaries of one’s skill set are reached. However, in this respect, the number of escalations only shows how restricted one’s response repository is. This, in itself, should be seen as a warning signal.

Of course, developing skillsets that span project teams is not easy. It requires the right people with a willingness to be empowered beyond their specialism, expertise and interest. It necessitates investment in training and support and a desire to retain highly skilled individuals. Additionally, simulations, refresher-courses or job-sharing can be crucial in ensuring that skills do not ossify or become obsolete – which in itself leads to additional expenditure.

A by-product of this form of project organising is that project team members with different skills and specialisms can find that they overlap each other. This is the antithesis of the silo mentality – specialisms, status and egos are less likely to get in the way of tackling the problem at hand, and this should benefit the project. This may require us to reconsider the nature of project efficiency. ‘Local’ efficiency – silos, expertise, tightly controlled work packages – may indeed work well and appear financially prudent, on paper at least. However, ‘broader’ efficiency in terms of a sufficient response capability may prove superior when difficulties arise and can be resolved more swiftly.

The power of empowerment

Project managers at TTP are empowered to make decisions regarding product development and customer service. The extent of responsibility and authority are given to them can be breath-taking. From the ‘cradle to the grave’ of a project, managers are not simple executors of project management activities but take on a whole variety of roles, such as commercial, legal, and project ‘ownership’, regardless of their original specialism. Such empowerment is by no means a comfortable proposition:

The benefits of empowerment are manifold, though. Project managers have a greater sense of purpose due to their extensive responsibility to look at a project from new and unfamiliar perspectives. This unfamiliarity, despite being uncomfortable, has the benefit of increasing their alertness and attention to problems that otherwise might remain hidden. Managers who extend their repertoire instead of delegating it to ‘experts’ see a situation with fresh eyes. They perceive more and are thus better positioned to notice and contain issues before they cascade into a crisis.

Seeing more and being able to put it together as a big-picture helps to maintain oversight of project performance. It helps to address the issue of risk blindness that is so often a problem of centralised and ‘specialist’ project organisations. Going hand-in-hand with greater alertness and vigilance concerning the unexpected, project managers at TTP feel firmly attached to their projects and their organisation. Not only is their expertise valued but so are their skills in going beyond their expertise and initiative to push the envelope beyond what they are comfortable with.

It is acknowledged at TTP that there needs to be a balance between empowerment and traditional management. Empowerment, as valuable as it might be, comes with potential challenges. A few find the responsibility overwhelming (and may leave). Senior management at TTP has to be sensitive to the needs of project managers as well as to the needs of the company and to know how to use a management style that will work best to achieve the desired outcomes. The principle of ‘letting go’ does not occur in a vacuum. A supportive culture (not to be confused with the traditional ‘command and control’ style) at TTP provides a ‘safe’ environment in which the responsibility of empowerment resting on a project manager’s shoulders should not become a burden and a constraint.

What is mindful about it? The benefits of empowering are manifold: higher job satisfaction, a greater sense of purpose and a greater incentive to engage with uncertainty beyond the risk horizon. A fundamental benefit of empowerment is the process by which we access knowledge, capabilities, skills, and resources to enable us to gain control over uncertainty. In other words, as empowered project members, we are more inclined to see a project through ‘fresh eyes’: raising questions otherwise not asked, challenging ourselves and others, or acting upon uncertainty instead of ‘escalating’ it away from us.

Simulations, games, rehearsals

Just as airline pilots simulate many possibilities before getting into a real cockpit for the first time, so too should we rehearse how to manage a project before we engage with it. The underlying purpose of a simulation is to shed light on the mechanisms that control the behaviour of a project. More practically, simulations can be used to predict (forecast) the future behaviour of a project and determine what might be done to influence that future behaviour. This is not to be mistaken with predicting or forecasting the future. It is about ‘testing’ how the project team operate under conditions that might be expected in the ‘reality’ of project delivery. Naturally, a simulation will vary from context to context and project to project, but simulations focused on the unexpected and hitherto unexperienced possibilities, are entirely feasible in almost all project settings.

Understanding our capabilities as a project team to engage with uncertainty, in a safe environment, can be achieved through various means, such as project management simulations, but also role-plays or exercises which stretch our senses about our way of working. In this respect, most project teams, unfortunately, prepare and ready themselves through overly abstract, detailed planning that fosters rigidity and inflexibility.

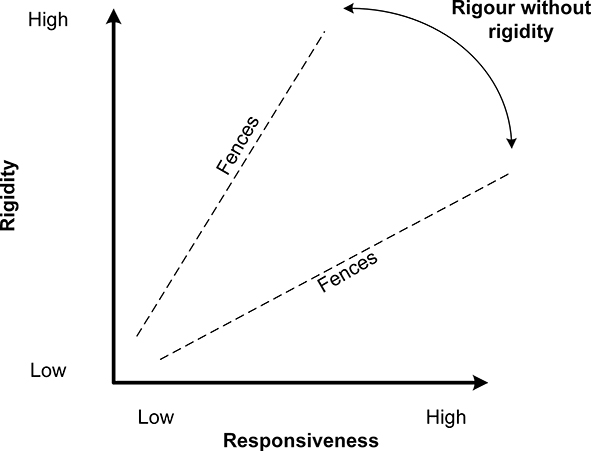

Routine-flexibility

Routines, the possible outcome of too detailed planning and the temptation to run a plan on autopilot, are valuable in stable, secure and repeatable environments in that they ensure consistency in managing uncertainty. However, many projects are often anything but stable. The idea of imposing rules and procedures on an environment in flux may be counterproductive. A way of limiting flux and creating the conditions for stability is to try to close the project off from outside influences. However, protecting it from changes by stakeholders and keeping uncertainty out may also mean inhibiting the possibility of enhancing value. For example, ‘protecting’ the project might mean preventing stakeholders, such as end-users, from getting involved in explaining what they want, especially when the project is underway. So, although boundaries (see Figure 5.2) around the project might protect the key deliverables by limiting opportunities for change, they also mean that the project is less likely to deliver precisely what the end-users actually need. If sponsors and funders are to draw maximum value from the project, then they will have to require project teams to allow them to get involved. This, in turn, exposes the project to the possibility of ongoing change and with that comes additional uncertainty. Rigid routines may collapse in this kind of environment, so what is required in projects is a degree of flexibility to adjust to the possibility of an ever-changing environment.

Figure 5.2 Freedom with fences

Flexibility, though, can be detrimental to project performance. Too much can become counterproductive, so project teams require latitude to be flexible yet must not lose sight of the rules and procedures that allow the project to keep on track. This concept was articulated at Harley Davidson and is sometimes known as ‘freedom with fences’ (Stenzel 2010). By adopting this approach, project members not only have the freedom to ‘push back’ where this might be required, but this very flexibility itself should become a routine, a kind of (dynamic) capability. Flexibility itself becomes the routine mindset. This approach needs to be understood and embedded in the mindset of the project team from the start, meaning that whenever uncertainty emerges, we are immediately able to loosen our ‘normal’ operating practices and respond with innovative and imaginative solutions and ways of working.

In this way, routine-flexibility is not the contradiction in terms that it may at first seem to be. Routines are produced by many people with different preferences, amounts of information and interpretations. This situation provides scope not only for stability but also for flexibility and change within organisations. Routines are the default position and provide boundaries within which flexibility can be exercised. Essentially, it is a matter of releasing the flexibility aspect and allowing it free rein, but within defined constraints: ‘fences’. Patrolling the fences (the limits of freedom) is the job of the project leader, who takes a strategic perspective on the project goals and ensures that changes enacted within the project in the face of uncertainty do not unduly threaten the project outcomes.

A sensible planning horizon

Given that a planning process will be undertaken in almost all projects, a vital issue will be how far we venture beyond the risk horizon. The risk horizon is defined by detailed, articulated, and actionable plans. The problem with thinking and acting too far out the risk horizon is one of fantasising: imagining a remote future that we hope, expect, or fear to happen, or preparing and readying us for a future that is so lofty that it provides no reference of a future at all.

Preparing and readying ourselves for thinking and acting beyond the risk horizon involves a discussion of how much we want to embrace the unknown. The question of how much stakeholders are willing to sensibly embrace the unknown beyond the risk horizon is only a starting point.

Goal flexibility

One aspect of uncertainty that sometimes gets forgotten is the alternative view of uncertainty as opportunities. Instead of just considering the negative implications, it can make sense to seek flexibility in the project goals and try to turn threats into opportunities. For example, regular planning iterations allow goals to be reassessed repeatedly, expectations to be managed, and learning from previous iterations to be incorporated. Each iteration is allowed to influence the next, and this process is quite transparent. This ability to be flexible with targets allows both for risks to be addressed and for opportunities to be incorporated. This is not suitable for every project, but even where stakeholders are quite clear on the outcomes and benefits they want from the work, a door remains open to adjusting those goals in light of uncertainty.

Leading the art of preparing

We need to be prepared and ready to deal with whatever might happen. We need to be vigilant in looking for uncertainties as they begin to emerge, alert to threats, and alive to opportunities. It is both confusing and counterproductive to seal the project off from its environment in the hope of ‘keeping uncertainty out’, and equally problematic (and more than likely, ineffective) to tighten rules and procedures in the hope of eliminating project failure.

Preparation commonly begins with standard risk procedures (routines) being put in place, but it is dangerous to leave things there in the hope that this covers all eventualities. The risk register should be just a starting point. It is incumbent on us to create a sense of preparedness and readiness among the project team so that they are not just ready for the expected but appreciate the threat of the unexpected, the unknown. This means empowering the project team, providing the freedom and latitude to act, and creating a culture of communication by removing the barriers that might prevent this, thereby enhancing flexibility. It also means, incentivising and rewarding project members to be constantly on the lookout for emerging uncertainty and committed to act upon it.

Training

Project management training is often related purely to conveying hard skills, such as how to apply processes and procedures. Although such training is beneficial and provides a project leader at TTP with a set of tools, TTP’s ‘Project Leadership Programme’ also emphasises the soft side of leading a project:

The ‘hard’ focus of training involves familiarisation with traditional ‘waterfall’ planning approaches such as Gantt charts and risk management. However, most of the time is spent on contextualising:

- leadership;

- conflict management;

- stakeholder/relationship management;

- time management;

- motivation.

Of great importance in this leadership programme is how it is conveyed, and a variety of methods are used to present learning material. These include TTP-specific case studies, role-playing, exercises and in-class simulations. This maintains the attention of training participants. Feedback is provided regularly, and participants engage in the exchange of ideas with each other and the facilitators. The training programme is divided into small ‘doses’, so delegates do not become overwhelmed. Acquired knowledge is then immediately applied in the form of interactive training sessions. Finally, a key factor is that the training programmes are designed to be exciting and entertaining.

What is mindful about it? The project management profession is often characterised as being trained in deterministic and probabilist planning techniques, enabling project managers to apply a project management framework (or body of knowledge) consistently. However, this training is unlikely to lead to a mindset of mindfulness and, thus, project managers are unlikely to be alert to epistemic uncertainty. In fact, the opposite is likely to be the case; an overreliance on consistency in action, informed by tools designed to predominantly address aleatoric uncertainty can reinforce mindless behaviour, however efficient it may be.

Training in the management of epistemic uncertainty can lead to greater awareness, inquisitiveness and more creativity and mental engagement with epistemic uncertainty. As a consequence, soft-skills training, focusing on adaptive leadership, team improvisation and constructive conflict management may be a good start of training to project managers.

Maintaining goal flexibility

If project iterations are implemented, a key aspect is not merely to progress to the next iteration but to ensure that a short phase of reflection occurs. Seeking to learn from the previous output and considering how this may influence the overall goal is valuable. These short but intense reflection periods may include questioning how the experience of the completed iteration affects the project delivery process and what that means for the overarching project goal. It is a reflection of how the creation of value (see Chapter 4) evolves. As a result, it is essential to communicate and sensitise people to the idea that nothing is set in stone and that the learning from an iteration informs subsequent iterations.

Empowering project members

Exhorting us to empower workers and staff to act on their own initiative can be difficult. There are two general problems: that we are reluctant to lose what we perceive as control; and that project members are unwilling to take responsibility. From the leader’s point of view, a transformational model can be far more effective than a transactional model. Transactional leaders focus primarily on role supervision, organisation and compliance, paying attention to work performed to spot faults and deviations. Transformational leaders focus more on being a role model, inspiring and keeping workers interested, challenging others to take greater ownership for their work, and understanding their strengths and weaknesses.

For transformational project leaders, empowerment can be promoted in several ways:

- To encourage on-the-spot feedback so that issues are communicated quickly and action can be taken immediately. The ground rules for such feedback need to be clearly set – it must be both constructive and respectful. Fundamentally, the project team must trust its leader and each other to deliver honest and helpful praise and criticism.

- To provide the empowered project actor with an abundance of expertise to allow the most informed decision making. In this respect, expertise is not supposed to ‘take over’ decision making but to support, guide, question and challenge.

- Project leaders can adopt an ‘executive mentality’ and approach. Hosting regular meetings with their teams and sharing with them the happenings within the organisation help the teams understand the main goals they are driving towards. Giving them a rundown on how other projects or parts of the organisation are performing makes it easier for them to adopt this mindset.

- It is crucial to present project workers with new challenges and stretch-assignments so they can demonstrate and achieve their full potential.

- Although project members should be encouraged to embrace new experiences, they cannot be pushed too far out of their comfort zones or the experience will become a negative one. Their boundaries must be respected. It is the job of the project leader to recognise and understand this.

- Empowered project members need to have some control over how they direct their work. This means having the freedom to express flexibility and creativity. It also means that project workers will act on their own initiative, but this flexibility needs to be within limits (freedom with fences), which must be explained to project staff.

- Giving up control and empowering a project team might feel like a very uncomfortable experience for many project leaders who are used to a more transactional model of control and compliance. The temptation is to watch the workers’ every move but, in monitoring someone closely, their ability to grow, learn, and build confidence to take action is impeded. The project workers need to be given space and need to be trusted.

Psychological reactance is the deep-seated and instantaneous reaction all people feel to being told they have to do something. This manifests itself as an unpleasant feeling people experience when they think they will lose their freedom to act (Brehm and Brehm 1981).

Examples of threats to the freedom to act can be found in all walks of life. For example, being persuaded to buy a specific product, being instructed to visit the doctor, being prohibited from using a mobile phone or being instructed to perform some task for someone in authority can all lead to psychological reactance. This can take the form of resistance (simply refusing to perform the task) all the way to purposely doing the opposite of what was ordered, seemingly to spite the one in authority giving the instruction. The extent of the reactance has been found to depend on the perceived importance of freedom under threat and the magnitude of the threat.

Reactance is very commonly observed in organisations, principally as a resistance to change being imposed on people. This has been found to manifest itself in numerous ways and acts at the level of the individual as well as the group (Nesterkin 2013).

Breaking down barriers

The way to break down barriers between silos is twofold. First, we should try and reduce the number of hierarchical levels, so that communication can flow more rapidly. Think of the flattest hierarchy possible. Second, empowerment in itself reduces the need for in-depth silos of expertise. Instead, ‘wider’ silos with extended insight and responsibility can be created. ‘Generalists’ can work as effective conduits of expertise between specialists, since they have broader (but shallower) domain knowledge and can be useful ‘boundary-spanners’.

This, though, is a rather structural option to breaking down barriers, which may take more subtle, behavioural forms. Culturally, egos and status may prevent the rapid flow of information. One way to overcome this is to work so that decision-making is driven by those who are the closest to the problem and have the most considerable expertise to deal with it.

In terms of geographically distributed (or virtual) teams, it is essential to promote some social interaction. Encourage people to meet or, if that is not possible, at least try to make sure they can see each other. Personal, real-time communication helps build trust and effective working relationships between non-co-located staff.

Helping people to get ‘close’ to uncertainty

We tend to be comfortable investing significant resources in ensuring that computer simulations are carried out on the technical aspects of engineering projects, especially where there is a risk of catastrophic failure that could lead to loss of life or high cost. As a result, engineering elements are carefully designed and rarely fail. However, the kind of simulations, role-playing and games that would be useful to prepare project members for the ‘soft’ risks of stakeholder interaction and behaviour are rarely undertaken outside a business school environment. Even where training like this does occur, it usually is in a sterile classroom setting.

We are responsible for ensuring that the project team is prepared and ready to tackle uncertainty and one way of preparing them is to undertake simulations, role-plays and games that allow you to experience and ‘feel’ the management of uncertainty. Although it is often tricky, we should try to find the time and resources to ensure that the project team has the opportunity to participate in these kinds of simulations and, in so doing, gets ‘close’ to how we work with each other in a tangible and memorable way, before we plan the project.

Role-plays, in particular, can fill participants with dread but some simple procedures can help ensure that the whole process goes smoothly and that the participants feel they are learning and getting close to risk and uncertainty. These are:

- Objectives. It needs to be clear about why the role-play is being undertaken, whether it is being assessed in some way and whether the activity is being tailored for different skills and experience.

- Timing. Is the role-play to be a one-off experience or is it part of a broader risk analysis/management activity? Frequently, it is held at the end of a training session or management activity with the idea that participants are then able to apply lessons learnt.

- Briefing. We need to be clear about what they are supposed to do. This should be supported by sufficient time to prepare, rather than just being rushed into a scenario.

- Observation and feedback. Observers can be hugely beneficial to participants’ learning and observation should be encouraged.

In summary, role-play events should be focused and clear. The participants should be able to see the relevance to their project and take their learning back to the workplace.

Incentivising beyond compliance

The reward and incentive scheme has to reinforce the open flow of communication required of the project team as well as support an open and ongoing discussion of project purpose. There are some techniques we can utilise to encourage the kind of focus required (Roberts et al. 2001):

- Use interviews and focus groups to ensure the real goals of the project are understood and shared.

- Review the reward and incentive procedures from the standpoint of balancing compliance to a framework with the adaptive capacity to deviate from a rule-based approach to project management.

- Develop and reward uncertainty identification activities and include these in staff evaluation.

The reward and incentive process needs to focus on both the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of a project team to engage with epistemic uncertainty in a mindful manner. Providing project members with greater autonomy and latitude to act, with fewer process and procedural constraints are in itself a powerful intrinsic motivator. Extrinsic rewards are in terms of financial and status outcomes. This reward system should be focused on communication and vigilance – supporting resilience – rather than just on speedy, efficient activity which may be too focused on the smaller, short-term picture.

A widespread cognitive bias, the self-serving bias involves taking the credit when things go well and blaming external factors when things go badly. It is so commonplace because it speaks to our own self-esteem. People can increase their confidence and self-esteem by attributing positive events to personal characteristics, while at the same time they can both protect their self-esteem and avoid taking personal responsibility if they blame outside forces for their failures (Larwood and Whittaker 1977).

There are many examples that can be found in everyday life. For instance, in a car accident the drivers might blame each other. Similarly, if a student does well in an exam, they may attribute this to hard work and dedication, whereas if they do poorly, they may blame poor teaching or distractions during the exam.

In organisations, self-serving bias can create a host of problems. For example, where people are looking to understand the results of actions, this can be undermined if they blame other factors for things going wrong. The result is that capability failings may not be addressed. Where organisations are developing risk plans, they are more likely to acknowledge external risks than to consider risks that might be generated from within the organisation. The same goes for security systems, where organisations are more likely to guard against external threats and downplay threats from within. Another example involves control mechanisms within organisations. As controls are developed by managers, these are more likely to focus on controlling the employees being managed than the behaviours and actions of the managers themselves.

The impact of preparing on relationships

The preparations for delivering a resilient project are not necessarily confined to the immediate project team. Any suppliers or contractors also need to be brought into the preparation processes. One aspect of preparation is dealing with the issues of power and politics. For this, attention also needs to be turned to other stakeholders: funders; sponsors; possibly end-users – in short, those stakeholders who could be particularly influential. As much as we need to be prepared for uncertainty that may arise as the project progresses, so too other stakeholders must be made aware that they themselves are a source of that uncertainty. They should be encouraged to focus on the ‘big picture’ as much as the little details, and also be alert to the weak, early signs of materialising uncertainty.

Engaging stakeholders in preparations

Just as the project team should be involved in preparations for resilience, so too should key stakeholders. In many ways, the same issues apply – they need to guard against complacency, be ready to be flexible and to let go of constraining procedures when uncertainty emerges. They might legitimately ask why they need to worry about all these issues of preparation towards uncertainty. The principal way of encouraging involvement in the process of addressing uncertainty is through appropriate incentives, which again should not focus on only simple task completion but more so on the mindful ability to adapt to materialising uncertainty.

Establishing long-term commitment

Projects are temporary endeavours and so too is the commitment to them. Engagement and dedication often do not extend beyond the duration of the work as people move on. Frequently, short-term and, in particular, long-term outcomes of a project become forgotten or are scrutinised by outsiders such as external assessors (whose expertise the project participants may question) who were not involved in the delivery of the project.

Aviva has sought to overcome this. The typical detachment and lack of long-term commitment to a project are countered by committing critical decision-makers to the long-term benefits beyond the duration of their project implementation. It all starts with the sponsor. A sponsor at Aviva is a functional manager – usually a director – for whom the project is expected to have a positive effect. The sponsor will bid for a project by developing a business case, to be scrutinised by an independent panel:

Such a business case outlines the traditional short-term outputs of a project (i.e. time, budget, specification) but also asks the sponsor to define outcomes that should apply two years after the end of the project. Some examples of these outcomes might include:

- increased efficiency in operations;

- reduction of legal vulnerability;

- improved public image.

The sponsor and the project manager share a collective responsibility to deliver both project outputs and outcomes, as they are intrinsically built on each other. Challenges are jointly addressed by the project manager and sponsor:

They tend to be measured subjectively by approximation. To address uncertainty in estimating these outcomes, some are defined with the help of approximations such as ranges (from-to).

At Aviva, the sponsor is committed to the longer-term, often difficult to measure, outcomes while the project manager concentrates on delivering the more specific short-term outputs. In particular, this arrangement drives the engagement of the sponsor in the project as well as in transferring short-term outputs into long-term outcomes. This form of engagement is further underlined by the impact of not achieving (or exceeding) initially defined outputs and outcomes. Both the sponsor’s and the project manager’s future prospects, including the type of projects they can sponsor or manage, are in play and there is an emphasis on incentivising the exploitation of opportunities to deliver something better, faster and at less cost next time:

What is mindful about it? Due to uncertainty, inherent in any project, those unmet short-term objectives may drive a wedge between stakeholders and the project delivery team, unless goal flexibility allows a project to change the goalposts in line with what is defined as value by stakeholders. Mindful project management involves a long-term commitment, beyond the risk horizon, towards attainable long-term goals. Mindful foresight beyond the risk horizon focuses one’s attention beyond the iron-triangle, beyond short-term goals cost, budget and meeting specifications. This attention drives a commitment to longer-term achievements and puts unmet short-term goals into a perspective of long-term benefits.

To drive long-term commitment, the project sponsor is primarily concerned with ensuring that the project delivers the agreed upon business benefits and acts as the representative of the organisation, playing a vital leadership role through a series of areas:

- Provides business context, expertise, and guidance to the project manager and the team.

- Champions the project, including ‘selling’ and marketing it throughout the organization to ensure capacity, funding, and priority for the project.

- Acts as an escalation point for decisions and issues that are beyond the authority of the project manage.

- Acts as an additional line of communication and observation with team members, customers, and other stakeholders.

- Acts as the link between the project, the business community, and strategic level decision-making groups.

Addressing discomfort

Goal flexibility and the commensurate implications of epistemic uncertainty for the planning process may well be uncomfortable for stakeholders. The idea of ever-shifting goalposts and using diverse ways to accomplish the project is difficult to justify. If not addressed, there is a possibility that the project manager will be labelled a ‘bad’ planner. Stakeholders need to understand why the planning horizon is shortened and need to be guided through the logic. We should offer advice, transparency and clarity about the planned state of a project, as well as about what we are not clear about.

Winning hearts and minds

The commitment of stakeholders to buy into a project and, importantly, into the uncertainty attached to it, is not solely driven by the project brief or by a contract that has been signed off. Central to committing people to a project is trust and respect:

Listening to, and understanding, stakeholders’ objectives and concerns and managing their need to have a greater understanding of what the project is, is all about helping to ensure that everyone is on the same page. The project leader delivering that message must:

- allow time to listen to stakeholders, being careful not to cut off a discussion because of other obligations;

- allow face-to-face conversation and personal interaction to allow social bonding;

- minimise external distractions by focusing attention on what is being said;

- keep an open mind;

- ask questions to clarify and to show enthusiasm about the message and the messenger.

Listening, per se, makes Aviva stakeholders ‘worthy’ – appreciated, of interest and valued. This is paid back as openness towards what the project stands for and how it affects them. However, listening needs to be followed by converting this openness into trust, a belief that the message – the project – is for the good of oneself and other beneficiaries. This depends upon credibility being established by providing honest feedback on the discussions. ‘How are concerns addressed?’, ‘How can objectives be aligned?’, ‘What questions help build up credibility?’ At Aviva, the action of establishing credibility is supported by ‘evidence’, be it benchmarks, case studies, or comparable projects where something similar has worked. Working together and finding compromises helps build credibility and allows trust to blossom.

What is mindful about it? A project is ultimately a social undertaking. Any project success, in the short- or long-term is down to the extent of social cohesion between stakeholders. Social cohesion works toward the well-being of project members; it fights exclusion and marginalisation, creates a sense of belonging, and most importantly builds trust within the project team in an environment that is inherently uncertain. Previously mentioned suggestions about role plays, simulations, and the use of devil’s advocates might all contribute to social cohesion, and thus contribute to task cohesion. This influences the degree to which stakeholders of a project might work together to achieve common goals. Social cohesion as the extent to which people in society are bound together and integrated and share common values is the bedrock of mindful project management!

Space Shuttle Columbia – a failure of preparing

The Space Shuttle programme was the fourth programme of human spaceflight at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), relying on a reusable spacecraft and solid rocket boosters as well as a disposable external fuel tank. The Space Shuttle could carry up to eight astronauts and a payload of up to 23 t to a low Earth Orbit. The fatal mission of the Columbia was designated STS-107, and was the 113th Space Shuttle launch since the inaugural flight on 12 April 1981 (STS-2).

On 1 February 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated, with the loss of the entire crew. After the 1986 Challenger disaster, it was the second fatal accident in the Space Shuttle programme that considerably tarnished the reputation of NASA.

During the launch of the Space Shuttle Columbia on 16 January, a piece of thermal foam insulation broke off from the external tank and struck the reinforced carbon panels of Columbia’s left wing. The resulting hole allowed hot gases to enter the wing upon re-entrance to Earth’s atmosphere.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board delved into NASA’s organisational and cultural shortcomings that led to the accident. A key issue was excessive pride or self-confidence of NASA in their readiness and preparedness to manage uncertainty:

In projects, repeated successes breed complacency in ones ‘invulnerability’, underlined by the lure of the fail-safe. To address such hubris, we need to remind ourselves that epistemic uncertainty remains prevalent and that we may be mindless in our appreciation of uncertainty. Also, the discomfort of not knowing what the future holds goes hand in hand with an incentive to establish mindful capabilities that allow a project to adapt to a changing situation by empowering front-line employees and providing tools and techniques to look beyond the risk horizon, but more so to act beyond it.

Towards an art of preparing

This chapter has been about resisting the temptation to prepare a project for a single, most likely future. Uncertainty means that this is unwise. Instead, a project needs to be ready for multiple futures, accepting the uncertainty that lies beyond the risk horizon. Providing an extensive repository of options, empowering people beyond their specialisms, breaking down barriers and silos between people, and the integrative role of stakeholders in exploiting this flexibility is paramount. Hence, resilience is not just an outcome of accurate and precise planning for the expected; it is an outcome of preparing a project for epistemic uncertainty.

Reflection

How well do the following statements characterise your project? For each item, select one box only that best reflects your conclusion.

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| We believe in the effectiveness of our management of uncertainty, although we have no proof about what we do not know with confidence. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The goal of the project is not set in stone but can be influenced by what we learn throughout the project. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We experience uncertainty before it happens, and do not just plan for it. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| Project members have an extensive skill set that enables them to act on uncertainty. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We are equipped with wide-ranging freedom to act, beyond process. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We are trained beyond our specialism. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| People can rely on each other without any barriers to overcome. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We share the discomfort of uncertainty with our stakeholders. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Our stakeholders are part of the preparation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Scoring: Add the numbers. If you score higher than 27, your preparedness beyond the risk horizon is good. If you score 27 or lower, please think of how you can enhance your state of preparedness in regards to epistemic uncertainty.

References

Brehm, S. S., and J. W. Brehm. 1981. Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. New York: Academic Press.

Buehler, R., D. Griffin, and M. Ross. 1994. “Exploring the ‘Planning Fallacy’: Why People Underestimate Their Task Completion Times.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67(3): 366–813.

Hershey, J. C., D. A. Asch, T. Thumasathit, J. Meszaros, and V. V. Waters. 1994. “The Roles of Altruism, Free Riding, and Bandwagoning in Vaccination Decisions.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 59(2): 177–871.

Jung, D. I., and W. H. Lee. 2016. “Crossing the Management Fashion Border: The Adoption of Business Process Reengineering Services by Management Consultants Offering Total Quality Management Services in the United States, 1992–2004.” Journal of Management and Organization 22(5): 702–197.

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. “Intuitive Prediction: Biases and Corrective Procedures.” TIMS Studies in Management Science 12: 313–273.

Klayman, J., and P. J. H. Schoemaker. 1993. “Thinking about the Future: A Cognitive Perspective.” Journal of Forecasting 12(2): 161–861.

Kutsch, E., H. Maylor, B. Weyer, and J. Lupson. 2011. “Performers, Trackers, Lemmings and the Lost: Sustained False Optimism in Forecasting Project Outcomes – Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment.” International Journal of Project Management 29(8): 1070–1081.

Kutsch, E., T. R. Browning, and M. Hall. 2014. “Bridging the Risk Gap: The Failure of Risk Management in Information Systems Projects.” Research Technology Management 57(2): 26–32.

Larwood, L., and W. Whittaker. 1977. “Managerial Myopia: Self-Serving Biases in Organizational Planning.” Journal of Applied Psychology 62(2): 194–981.

Mason, R. O. 2004. “Lessons in Organizational Ethics from the Columbia Disaster: Can a Culture Be Lethal?” Organizational Dynamics 33(2): 128–421.

Mutz, D. C. 1998. Impersonal Influence: How Perceptions of Mass Collectives Affect Political Attitudes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nesterkin, D. A. 2013. “Organizational Change and Psychological Reactance.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 26(3): 573–945.

Parasuraman, R., and D. H. Manzey. 2010. “Complacency and Bias in Human Use of Automation: An Attentional Integration.” Human Factors 52(3): 381–410.

Parasuraman, R., R. Molloy, and I. Singh. 2009. “Performance Consequences of Automation-Induced ‘Complacency.’” The International Journal of Aviation Psychology 19: 1–23.

Roberts, K. H., R. Bea, and D. L. Bartles. 2001. “Must Accidents Happen? Lessons from High Reliability Organizations.” The Academy of Management Executive 15(3): 70–79.

Stenzel, J. 2010. “Freedom with Fences: Robert Stephens Discusses CIO Leadership and IT Innovation.” In: CIO Best Practices: Enabling Strategic Value with Information Technology, edited by J. Stenzel 1–23 Cary: SAS Institute Inc.