CONTENTS

Key enablers to the art of interpreting

Mindful practices: risk interdependencies

Mindful practices: maintaining and retaining knowledge

Leading the art of interpreting

Mindful practices: project management software

The impact of interpreting on relationships

Deepwater horizon – a failure of interpreting

Project uncertainty is in the eye of the beholder. It’s an interpretation of what we do and do not think we know. It is based on interpretations and judgement, a product of social interaction, a continuous construction and reconstruction. In a project, we continually seek to make sense of what is going on, and the nuance of this process of making sense of the world is crucial to the management of uncertainty.

At the beginning of any uncertain endeavour, stakeholders will probably demand certainty. In other words, the question of ‘What will it all mean?’ is central to the discussion at a point when stakeholders long for the comfort of having confidence in a simple, predictable, controllable future.

The lure of simplicity

In order to cope with uncertainty, we tend to simplify, so that we can move on. We filter out cues in the environment that prohibits forthright action. The process of simplification is inherently detrimental to the management of uncertainty. It reinforces complacency and ignorance of the attendant uncertainty. Processes of simplification may do little more than result in an illusion of control.

Structural oversimplification

A project is often understood in terms of its constituent elements, for example, using a work breakdown structure. This produces a seemingly (relatively) simple set of tasks and activities, and there is a corresponding tendency for the project team to regard the project as being reasonably straightforward.

Because we tend to look at aspects of adversity in isolation, we often tend to pay little heed to the ‘big picture’. Aristotle’s famous ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ is valid in projects, too. By applying traditional planning tools, we can emphasise our tendency to oversimplify and thus underestimate uncertainty and complexity. This uncertainty and complexity is not just related to the specific activities, but also their inter-relationship as a project system and the project’s connection to other, related projects and the wider supply network and stakeholder community. Projects are all about inter-relationships and interdependencies and failure to understand this is to seriously underestimate inherent epistemic uncertainty.

First described by Weinstein (1980) in the 1980s, irrational optimism bias is perhaps the best known among the many cognitive biases under which all people labour. For many decades, scientists have recognised that people tend to underestimate their chances of negative experiences while overestimating their chances of positive experiences (Shah et al. 2016). Optimism bias – sometimes called the ‘illusion of invulnerability’ or ‘unrealistic optimism’ – has, at its heart, a natural inclination among people to exceptionalism. This means that we have regard of ourselves that is greater than that of people in general, a perspective that gives rise to the term the ‘personal fable’, describing the view we hold about ourselves as the protagonist in our own life story. The consequences can be profound. It manifests itself in personal beliefs we hold about ourselves and our immediate family such as that we will live longer than the average, that our children will be smarter than the norm and that we will be more successful in life than the average. By definition, however, we cannot all be above average.

The point about optimism bias is that our tendency to overestimate outcomes of our actions means that people make poor decisions (Sharot 2016). In our personal lives, people take unnecessary risks as they feel they will not suffer detrimental consequences. For example, people might choose not to wear seatbelts, or to use their mobile phone while driving. Here, they are overestimating their driving skills. Similarly, we might not see the doctor when we need to because we overestimate our health.

That said, optimism bias is not always problematic. The benefits of optimism bias are that we are more likely to pursue our goals and take risks required to achieve objectives. Without optimism bias, some things would never be attempted. This gives rise to a conundrum. If people overestimate their chances of success in the things they do because of optimism bias, they are likely to make poor, mindless decisions. However, optimism bias is essential so that people attempt any undertakings they might otherwise reject as being too risky (Sharot 2016).

What applies to our personal lives also plays out in organisational life (Kahneman and Lovallo 2003). The same poor decision-making in our everyday lives can easily translate into poor decisions in business investments or government spending. In a study, 11,600 Chief Financial Officer (CFO) forecasts were compared against market outcomes, and a correlation was found of less than zero. This shows that CFOs are grossly over-confident about their ability to forecast the market (Kahneman and Lovallo 2003). While optimism is vital to having persistence in the face of obstacles, pervasive optimism bias can be detrimental. For example, only 35 per cent of small businesses survive in the US. When surveyed, however, 81 per cent of entrepreneurs assessed their odds of success at 70 per cent, and 33 per cent of them went so far as to put their chances at 100 per cent.

While this may not be such a problem in smaller-scale organisations, when it involves significant capital investments, optimism bias of this nature can be disastrous for organisations. It results in capital being invested in projects that never had a chance of receiving a return, or of excessive tax income being invested in projects that have small benefits. More importantly, when things start to go wrong, people in organisations have a tendency to overestimate their ability to get projects back on track, which means they pursue objectives with no realistic chance of achieving them, even when this becomes apparent.

A good example was the dramatic rise and sudden downfall of Theranos. The company was set up to develop technology to carry out a barrage of blood tests quickly and simply from just a few drops of blood. The benefits in terms of savings both of blood test costs and lives through quick results were tantalising but the CEO, Elizabeth Holmes, grossly overestimated the ability of her company to successfully develop the technology required while large American firms and famous investors such as Walgreens and Safeway invested hundreds of millions of dollars into an unproven technology, over-optimistic of its promise and the abilities of the team at Theranos to deliver it (Carreyrou 2018).

Optimism bias is more likely to occur where events are infrequent, such as one-off projects. People are also more likely to experience optimism bias where they think they have direct control or influence over events. This is not because they believe that things will necessarily go well in some fateful way, but that they overestimate their skills and capabilities to control things. Finally, optimism bias is likely to occur where the negative consequences of an undertaking are perceived to be unlikely, even if this perception is misplaced. By contrast, experiencing certain events for real can reduce optimism and people, it has been found, are less likely to be over-optimistic when comparing themselves to very close friends, family and colleagues (Sharot 2016).

As can be seen, optimism bias has benefits and problems. It is necessary to be optimistic to motivate employees and keep them focused, and optimism encourages people in organisations to take challenges and not be overly risk-averse. However, optimism bias tends to be more about enthusiasm than realism (Kahneman and Lovallo 2003) and, therefore, organisations have to find a way of maintaining a balance between over-optimism and realism. For organisations, perhaps the most important thing to do is to draw a clear distinction between the individuals, where optimism encourages vision and innovation, and functions tasked with supporting decision-making, where mindful realism should prevail (Kahneman and Lovallo 2003).

‘No effect on me’

Going hand-in-hand with optimism bias is the belief among many that adversity will not affect our project. We have planned it meticulously and carried out a detailed risk planning and management process. Just as no one on their wedding day believes that their marriage will end in divorce, so too do we tend to think that our project is invulnerable or, perhaps, impervious to adversity. We do not believe this is without agency – we feel that there is something special about us and what we do that will avert problems, either as individuals or as a collective. The result is that we are likely to focus on ‘doing the job’ (e.g. working on project tasks) rather than looking for those early, weak signals of uncertainty. Adversity may hit other projects, but it will not happen in this – our – project.

The realm of probability and impact

The process of risk management is driven by a relatively simple principle – the likelihood of an event occurring and the probable impact should that event occur. This straightforward approach (likelihood × severity) underpins nearly all standard risk assessments. The orthodox approach is to focus on those risks with a high combination of the two and ignore, or downplay, those with a low probability of occurrence or a little impact should they occur, or both. This can be problematic, as traditional risk assessments do not tend to capture what we do not know, or in other words, what risks we are not confident about. It is a striking feature of typical risk management process in project management that the extent of epistemic uncertainty is not advocated to be measured.

Estimates become commitments

The future is difficult to predict accurately and to explain, but at the beginning of projects, this is precisely what we are asked to do. We are required to forecast the duration and cost of a project, frequently in the face of intense uncertainty. The estimate we arrive at is essentially the process of putting a value against that uncertainty, governed by a combination of experience and the information available at the time. Owing to the subjective nature of estimating, it can be an inherently personal, human-made, fact-based fiction that we tell ourselves about the time and resource commitment necessary to complete a task. This is a function of not only the project’s inherent difficulties, but also our capacity to combat them. Perhaps the fundamental problem with estimating projects is that the estimate is based on an idealised conception of productivity – an idealisation often based on optimism. The real problem happens when the project team and sponsors equate the estimate with a firm commitment. This can have an unwanted effect on behaviours (such as Anchoring). Organisations that demand adherence to original estimates unwittingly promote ‘padding’ in the next set of estimates to increase the likelihood of meeting them. Too much padding – although a perfectly rational response from each individual’s perspective – makes the estimate uncompetitive and may lead to the loss of a bid or the work not even being funded.

When estimates have become commitments, these commitments serve as anchors for subsequent decisions about what resources to commit to the project. The tendency to do this is due to over-optimism about the reliability of the estimate. Because of the optimism bias that was built into the original figures, any subsequent analysis is also skewed to over-optimism. Data disconfirming those estimates are discounted, and those reinforcing the estimates are amplified. The results are exaggerated benefits, unrealistic costs, and an almost inevitable project disappointment.

Another cognitive bias that has long been recognised (Tversky and Kahneman 1974), and can be found both in peoples’ everyday lives and in business, is anchoring bias, sometimes referred to as focalism. It occurs when people over-rely either on information they already possess or on the first information they find when making decisions. In an often-quoted example, if someone sees a shirt priced at $1,000 and a second priced at $100, they might view the other shirt as being cheap, whereas if they had only seen the $100 shirt, they would probably not view it as a bargain. The first shirt in this example is the anchor, unduly influencing the opinion of the value of the second shirt. That said, it has been found that anchoring only occurs typically where the anchor information is not ridiculous (Sugden et al. 2013). However, if the anchor figure is not perceived as being ridiculous, even arbitrary numbers can be found to act as an anchor.

Anchoring can happen in all sorts of aspects of daily life. For example, if both parents of someone live a long life, that person might also expect to live a long life, perhaps ignoring that their parents had healthier and more active lifestyles than they do. If a person watched a lot of television as a child, they might think it is acceptable for their children to do the same. In healthcare, a physician might inaccurately diagnose a patient’s illness as their first impressions of the patient’s symptoms can create an anchor point that impacts all subsequent assessments. These are all examples of anchoring, where people make estimates by starting from an initial value that is adjusted to yield the final answer (Tversky and Kahneman 1974).

Marketing departments have long recognised the power of anchoring to influence customer purchasing decisions. For example, a retailer may purposely inflate the price of an item for a short period so that they can show a substantial discount. The inflated cost acts as the anchor making the product seem relatively cheap (Levine 2006).

In organisations, anchoring can frequently be seen at play (Daniel Kahneman and Lovallo 2003). Where organisations are making investment decisions, anchoring is particularly pernicious. A team might draw up plans and proposals for an investment based on market research, financial analysis, or their professional judgment before arriving at decisions about whether and how to proceed. On the face of it, this is uncontroversial, but all the analysis tends to be overly optimistic and is often anchored to whatever the initial budget or estimate happened to be (Kutsch et al. 2011). It can go as far as whole teams of stakeholders developing a delusion that their accurate assessments are entirely objective when, in fact, they were anchored all along (Flyvjberg 2005).

Amnesia

We often try to put difficult or trying times behind us by simply forgetting about them – ‘out of sight, out of mind’. Attention moves on to something else (for example, a new project) and we frequently stop thinking about the difficulties we previously faced. This can happen simply because we do not want to think about troubling times, or because some project members move on (retire, move to new organisations) and knowledge is dissipated. Having to tackle emerging uncertainty is painful, uncomfortable for us. It is no surprise that we will forget about them over time. It is a well-established phenomenon within the literature that organisations struggle to learn from previous projects.

The perception of losses and gains

We tend to interpret potential gains and losses differently. Facing a loss triggers stronger stimuli to respond than facing a gain or an opportunity. In a project, a potential loss may thus receive more attention than is given to a possibly more valuable opportunity. Once materialised, actual losses may be a focus for attention while more beneficial opportunities remain under- or unexploited. This response system can create a spiralling effect, where we stubbornly try to make up for lost ground, missing alternative options that would, when viewed objectively, offer more advantageous uses of time and resources.

For many people, losses loom larger than gains. As a result, people try to avoid losing things more than they seek to gain things of equivalent value (Kahneman and Tversky 1991). Having to give up objects makes people anxious and, ironically, the more people have, the more anxious they feel at a possible loss. Psychologists have found that the pain of losing something is almost twice as powerful an emotion as the pleasure of gaining something (Rick 2011) and explains why people are more likely to take greater risks (and even behave dishonestly) in order to avoid losses (Schindler and Pfattheicher 2017). This manifests itself in everyday life, for example, feeling blame more acutely than praise. There is a central paradox to loss aversion. People tend to be risk-averse when faced with the possibility of losses and, at the same time, are prepared to take risks to avoid those same losses.

Loss aversion bias can manifest itself in a number of ways in organisations. The three most common are:

- The endowment effect, where people are reluctant to invest in new capital because they overvalue what they already have, regardless of its objective market value, and forgetting that things depreciate (Kahneman and Tversky 1991).

- The sunk cost fallacy, where people continue with a plan or endeavour despite getting no gain from it because of the time, effort and resources already committed to the endeavour (Arkes and Blumer 1985).

- The status quo bias or conformity, where people stick with earlier decisions rather than drop them for new courses of action. This is a significant problem for organisations seeking to implement change as it breeds inertia and closes people off to opportunities and solutions (Ryan 2016).

Overanalysing

The opposite pole to oversimplification is overanalysing. We may be tempted to devise the ‘perfect’ plan that is very detailed and provides a supposedly accurate picture of how the project will unfold. Analysing in too much detail may strip us from paying attention to what the plan does not tell us, of how much we do not yet know.

The danger is that we end up ricocheting from one extreme to another; from oversimplification as a means to move on to overanalysing to provide us and our stakeholders with details and an illusion of certainty. Both extremes are detrimental to our ability to deal with epistemic uncertainty.

Key enablers to the art of interpreting

Our interpretation of uncertainty and complexity is clouded by cognitive biases, preventing us from think mindfully about the future. What can we do about it?

Big picture thinking

To find the right balance between oversimplifying and overanalysing the future of a project, big picture thinking is essential. Looking at the big picture involves trying to see the entire scope of a task or a project, as an entity, a system and a network of systems. This can be a tactical way to obtain a full sense or understanding of things.

So, what are these big strategic questions that we may not be spending enough time on or are not answering in a sufficiently clear or disciplined way? They are questions about:

- why the project exists and what its purpose is;

- what it offers (and does not offer) its stakeholders, and how and why this these offers deliver value to customers,;

- what this produces for the stakeholders – the critical outcome metrics by which the project will be judged;

- and how the people within the project will behave – toward stakeholders, and each other.

Devil’s advocate

There is a misconception about seeking consensus and direction in decision-making through people’s engagement in dialogue. This is generally not the best approach if decisions need to be made not only quickly but also effectively. Dialogue involves conversations between people with mutual concerns but no task-orientation or any necessity to persuade others to accept a position. What is more useful in decision-making, where task and direction are essential, is dialectics. Dialectics privilege rationality in an argument to arrive at a consensual ‘truth’. The role of the ‘devil’s advocate’ is influential in arguing against that dominant position of a simplistic future. That role is to resist and to point out flaws in deeply embedded simplification of a future state a project. The devil’s advocate increases both the number and quality of decision-making alternatives and can be a catalyst for new ideas. Devil’s advocacy can be used both in early decision-making stages and also as a post-decision critique. It usually is best undertaken by someone separate from the group: an outsider who is both structurally and emotionally detached from the project or problem being considered.

Risk interdependencies

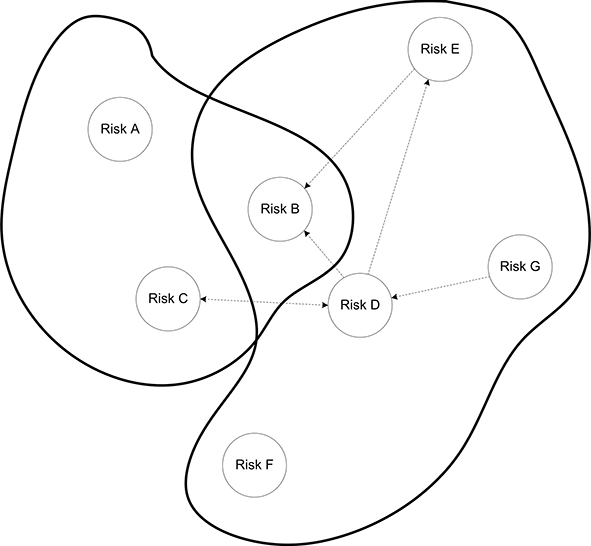

At Aviva, the issue of interdependencies between risks is actively addressed. In doing so, Aviva is seeking to acknowledge that one risk may influence other risks, not only within the boundaries of a single project but, possibly, also across project and organisational boundaries. A range of tools is utilised to encourage project leaders to think about risk interdependencies. One tool that can easily be applied to address risk complexity is causal mapping. Causal mapping has its origin in strategic management but can be used in any context that involves some complexity. At Aviva, this consists of visualising interdependencies, which are then mapped, often in the form of a cognitive map or mind map (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Example of a causal map

In this example, particular attention has to be paid to Risk D, as it influences other risks beyond the project boundary.

There is no single right answer as to how to develop these causal maps. Elements can be coloured differently, for example, to highlight risks that affect critical components in one or more projects. A key objective of such maps, however, is to trigger an exploration of problems – risks in this example – but also solutions. As much as risks can interact with each other, so can solutions.

Aviva sees both uncertainty and complexity as issues to be addressed through understanding the interrelationships and seeking practical solutions. To some, it may seem a futile exercise to move beyond the isolationist management of risk to explore risk and response interdependencies. For others, it is a revelation that provides another step in appreciating complexity in modern-day project management.

What is mindful about it? Perhaps first and foremost, we should be helped to understand the interdependencies between different parts of the project, between the project and the wider environment and between the various stakeholders. There are several strategies that can be used to help us think in terms of connections and relationships. For example, liberal use of ‘rich pictures’ associated with soft systems methodology (SSM), can help people understand the interconnectedness of project systems. SSM focuses on seeing project systems as mental models of interconnection and is a way of revealing and understanding different world-views. Understanding connections between elements of a system and across different systems is the first step in avoiding oversimplification and over-optimism. It illustrates, in a very vivid manner, the complexities of a project and the scope for uncertainty to emerge.

Memory

For projects, organisational amnesia means that past risks, and their causes can easily be forgotten. A way of tackling this phenomenon is to refresh the memory and surface previous, possibly unpleasant or painful, experiences. Although a wide range of IT-based codification systems has been developed, it is crucial to recognise the importance of relationship-based memory within the organisation. Although it is widely studied in the academic literature, the value of social interaction is often underplayed within practitioner-focused work. ‘Social capital’ (which is comparable to financial or human capital) is often vital in ‘getting things done’, and most managers intuitively recognise this. Because it is a somewhat intangible concept and hard to quantify, though, we are generally reluctant to try and ‘manage’ it. However, strong relationships build trust and a network of trusted colleagues built over time is hugely valuable. Speaking to someone and using their knowledge often also seems more ‘real’ and relevant, and even more trustworthy, than reading documents in a lessons-learnt database. In a team-based environment, members also soon learn ‘who-knows-what’, and this, in turn, leads to efficiency in knowledge-sharing and knowledge generation that surpasses what would be the case in a newly-formed team.

To encourage these activities, some practical things we can do are to put in place mechanisms for reflecting and learning from experience; to focus feedback from peers or managers on experiential learning and to support learning both within the team and from outside the team through the sharing of experiences. Some mechanisms that can be put in place to support this kind of learning and prompting of memories are communities of practice and the use of storytelling techniques. The latter are often rich and provoking and constitute an effective way of learning and fixing experiences in mind.

Maintaining and retaining knowledge

While working on a project, it is important to understand what the significant knowledge is (the ‘how’ of the work), and who the best people are to go to for expertise and advice. Ensuring that this is effective, and that staff can learn from such experts, is a key part of practical knowledge management. As one project manager told us:

At Intel, despite the inherent uncertainty in the problems, solutions and stakeholders they are engaged with, they try to maintain pools of project teams so that knowledge and capabilities are as stable as possible. They will add understanding if required. Technical expertise, as well as familiarity, are brought together and maintained.

This ‘pooling’ of knowledge, however, does not guarantee a commitment to retain it over time. With increasing experience, valuable knowledge workers may be promoted away from where their insight is most useful. Promotion of skilled and knowledgeable staff can deprive projects of expertise. To deal with this problem, Intel developed a culture that encourages experts to remain close and committed to the project at hand. As we were told:

What is mindful about it? To retain knowledge, one could offer a monetary incentive. That is not necessarily the best route, though, since if we are paid more for our specific expertise, we have a strong disincentive to share what we know. This can reward entirely the wrong behaviours. Looking more broadly, knowledge experts:

- tend to be specialised, yet have an interest in looking beyond their specialism. Employers may offer insights and challenges from different perspectives.

- tend to believe in independency and often do not like to be ‘boxed in’ by hierarchy. It is not the hierarchical position that defines a knowledge expert but the value they can offer. The meaning in their work is not limited by status per se but by the development of knowledge that can be accessed for the good of the project. The respect of peers is a strong motivator.

- tend to be lifelong learners. They constantly need to maintain their interest by being challenged and pushing their boundaries. Allowing them to do this and offering them these opportunities keeps them interested, and thus committed and more likely to stay within a project team.

Value-driven project management

The reason projects are undertaken is to deliver value for the organisation (whether private-, public- or third-sector). This may involve specific products or services and can even encompass safety and regulatory compliance projects. Given (broadly) that business or taxpayer value is the reason for doing projects, it makes sense that there is a focus on value-driven delivery. The concept of risk is closely associated with value, so much so that sometimes we think of risk as ‘anti–value’. This is because, if they occur, risks have the potential to erode value. The notion of value is also closely tied to differing definitions of success, with project delivery criteria in terms of budget and time frequently overlapping only briefly with the actual business needs of the sponsoring organisation. So, following a project plan to conclusion may not lead to success if value-adding changes are not implemented effectively.

The purpose of value-driven project management is to shift the focus from the detailed delivery of project activities to understanding what value means for a customer and end-user stakeholders and, in doing so, concentrating on what matters in the project. If the project team is concentrating on this value, then their focus is what ‘matters’.

There are some techniques associated with this kind of value approach that can be employed. Many have the added advantage of emphasising the creative potential of the project team. Techniques that might be applied to enhance project value include:

- Functional Analysis (sometimes called the ‘functional analysis systems technique’ – FAST). This is a method of analysis that can be applied to the individual functional parts of a project, identifying and emphasising the intended outcomes of the project as opposed to outputs or methods of delivery. Each aspect can be described with a ‘verb-noun – phrase or adjective’ combination, which focuses the thinking.

- Life-cycle costing and whole-life value techniques. Here, the focus is on how costs are incurred and value derived from the outputs of a project right through its useful life. Costs that might be considered include the original development costs, plus the deployment costs over its lifetime (the total running costs including maintenance and repairs) and any decommissioning costs. In some industries, such as the oil industry and civil engineering, sophisticated modelling is used to establish whole-life value, although the approach founders on how value can be defined.

- Job plan and creativity techniques. Using brainstorming approaches, frequently in multi-disciplinary groups, means that many new ideas can be generated quite merely by asking precise questions. Asking ‘How can we do this better/faster/cheaper?’ or ‘How can we apply what we know to a new product or market?’ can generate valuable answers in a short time. There is rarely a single, simple, solution to such problems, and these approaches are particularly useful in encouraging creativity in the project team.

Leading the art of interpreting

Over-optimistic forecasts of likely project performance, based on underestimating aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty in projects, coupled with an over-optimistic assessment of the project team’s ability to deal with uncertainty, are significant problems for project decision-making. As we have seen, estimates tend to become commitments that, in turn, become anchors for later decisions. Worse still, people are cognitively hardwired to be optimistic, either for political reasons (getting the project funded or awarded in the first place) or (more often, perhaps) psychologically. We delude ourselves, and we are all complicit with each other in that delusion.

The problem faced by us is that we have to find ways of countering this tendency – of stepping back, looking at the project plan with more realistic, dispassionate eyes and injecting some reality (perhaps even pessimism) into the planning process. We are often unable to be mindful as we are too involved in the ‘process’ and areas subject to the same cognitive biases as everyone else involved in the work. As a consequence, we must take a leadership role, focusing on people rather than structure and process, taking a longer-term rather than shorter-term view, challenging the status quo and being innovative rather than administrative. Beyond the practical things that can be done to help balance out optimism bias and organisational amnesia, we have a crucial role in shaping the forecasts and avoiding over-simplification of the uncertainty involved in delivering the project.

Asking inconvenient questions

If we can emotionally and structurally detach ourselves from a project (a difficult enough task in itself) we can (as required) slip into the role of devil’s advocate that all projects require to combat our tendency to oversimplify. We will be able to challenge the ‘inside view’ and project an ‘outside view’ that may be more realistic: prompting our memory, encouraging experts to recall past projects and consider what may go wrong, why it may go wrong and how we could deal with uncertainty. The focus of questioning is to probe limitations in everybody’s biased expectations of a future state of a project, and not to question anyone’s competence. As inconvenient as these questions may be, they are essential in challenging oversimplification and in encouraging mindful ways of thinking beyond the risk horizon.

The overconfidence effect is a cognitive bias observed when people overestimate their ability to do something successfully. Specifically, their subjective confidence in their ability to do something is not borne out by their objective ability (Pallier et al. 2002). There are three distinct ways in which the overconfidence effect can manifest itself. These are:

- Overestimation of one’s actual performance where, for example, someone overestimates their ability to tackle a problem within a specific time limit. Overestimation is a particular problem with complex tasks, although it has also been found that, with simple tasks, people tend to underestimate their abilities. In psychological experiments, this effect was found to form about two-thirds of all manifestations of the overconfidence effect.

- Overplacement of one’s performance relative to others sometimes called the ‘better-than-average effect’. A typical example is that when asked about their driving abilities, 90 per cent of people believe themselves to be in the top half. It has been found that this forms a relatively small proportion of instances of the overconfidence effect.

- Excessive precision in one’s beliefs relates typically to people’s overconfidence when estimating future uncertainties and usually is found where people are making forecasts about the future in, for example, risk analysis. This particular expression of overconfidence accounts for just under a third of occurrences. (Don Moore and Healy 2008)

Overconfidence in one’s ability and knowledge, is a problem that affects people from all walks of life and in all sorts of situations. It has been blamed for everything from the sinking of the Titanic to the Great Recession. In an organisational environment, it is thought that overconfidence is a widespread problem (Healy 2016). It is argued that in complex organisations, people need to stand out to have their ideas considered, and this, in part, leads to overconfident people having undue influence over the direction of organisations. It can be seen in stock market assessments, in estimates of the success of mergers and acquisitions, in the estimates of profit forecasts and in many other aspects of organisational activity.

There are a number of possibilities to explain unwarranted overconfidence. One theory suggests that it is related to the initial best guesses that people then anchor to (Tversky and Kahneman 1974). Other theories suggest that when communicating with others, people prefer being informative to being accurate (Yaniv and Foster 1995), while another theory suggests that overconfidence reflects extremely poor starting point guesses (Moore et al. 2015).

Despite overconfidence being an almost ubiquitous cognitive bias in organisational behaviour, managers can do some things to lessen the effect, as long as they recognise that it is an issue that needs to be considered in decision-making. One strategy is to conduct a ‘premortem’ (see Chapter 8), where people are asked to list arguments that contradict the reasoning that led to the guess in the first instance. Another approach is to assume the first guess is wrong and then adopt alternative reasoning to derive a second guess. Averaging these two guesses is likely to be more accurate than relying on the first guess alone (Herzog and Hertwig 2009). One more strategy uses the ‘wisdom of the crowd’. This approach involves collecting guesses from other stakeholders and using these guesses as the basis of one’s own guess (Hogarth 1978).

Focussing on opportunities

A bias towards the negative side of uncertainty may make us ignore the potential upside in the form of opportunities. We can try and draw attention to how the team could deliver project outputs and outcomes faster, better and cheaper. This is only valid in projects in which deliverables are not set in stone but have incentives for stakeholders to explore and exploit opportunities. It is always valuable to ask the ‘Why don’t we?’ questions, countering loss aversion bias. A positive approach is to establish an entirely separate entity (e.g. a Tiger Team) within the project to break from legacy thinking. Doing this creates different mental and physical spaces to create a balanced view on losses and gains.

Distinguishing between noise and ‘relevant’ uncertainty

In adopting a dialectic decision-making role, we can encourage a focus on what matters (value); the issue is to distinguish between what matters and what does not. Based on an active reporting culture, we may be bombarded with stakeholders’ concerns and flooded with ‘what might go wrong’ in the project. It is our job to filter out important messages from the abundance of ‘noise’. In order not to discourage any report of impending failure, consider all messages as important, though. With the help of the messenger, raise some important questions such as:

- Has this happened before? Is it an indication of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty?

- Might it influence a part/function of the project that is critical?

- How close have you been to this emerging uncertainty? Do we require more information?

- How quickly could this cascade into a more significant threat?

- What value in a project may it affect?

These kinds of questions can enable effective decisions to be made. We can filter out the less critical uncertainties and concentrate on those that will impact on value. Be sensitive, though, to the idea that the messenger may be conditioned by optimism bias.

Project management software

Project Management Software can facilitate the activity of scheduling and estimation. It helps to cope with the abundance of information. Aviva uses commercially available project and portfolio management software as a tool to provide critical information in real-time. This system standardises, manages and captures the execution of project and operational activities and resources. It comprises several modules and components to allow the management of project finances, time recording and resources, including demand, risks and issues.

By using one system to manage multiple functions, the project manager can keep all essential information in a single location that is also available to other team members and is therefore easy to keep up to date:

What is mindful about it? Accessing information is not the only benefit a software tool provides. It should also offer the following:

- Memory: it should be a reminder of the uncertainty and complexity. For example, the system probes the project’s commitment to interpreting risk and uncertainty and refreshes participants’ ability to do so:

- Simplicity: allowing the ‘simplification’ of data (but be aware of the danger of oversimplification) to aid decision making.

- Nuanced appreciation: it should allow one to distinguish between ‘hygiene’ factors and novel adversity. Hence, it should help identify patterns across projects and flag up any uncertainty.

- Communication: facilitating instant communication. Timestamps highlight how up-to-date the information is.

- Confidence: providing evidence of the validity of the information. It should help to probe uncertain aspects.

- Challenge: it should not replace the project leader’s role in asking inconvenient questions but should help to tackle people’s optimism bias.

Addressing the big picture questions

Our responsibility as a project leader is not only to challenge people on their perceived degree of certainty, anchored in detailed planning, but also to create a desire in them to be on the lookout for problems, report the possibility of failure and share their perceptions with other members of the project team. In other words, they need to be alert to emerging uncertainty. Alertness, however, requires addressing the ‘So What?’ question (see Figure 4.2), beyond the boundaries of project tasks.

Figure 4.2 Big picture thinking – problem

- Make choices in the negative. For everything you decide you want to achieve in a project, articulate what that means you can not do. This forces you to think through the consequences of choosing these options by thinking about what the trade-offs are for each choice you are making.

- Pretend the project has no money. When projects are strapped for cash, project decision-makers have to make hard choices about what to spend money on because they do not have enough. It is often during such times that leaders describe themselves as at their most strategic. But it is easy to diet if someone’s padlocked the fridge – what happens when you get the key back? All too frequently, when the cash starts to flow again, leaders start ‘choosing everything’ again, and it’s this that sows the seeds of the next bout of underperformance. Having too many priorities means you do not really have any, which puts your project’s implementation capability under strain. It also compromises your own leadership bandwidth, reducing your ability to macromanage. So pretend you are cash-strapped – it will act as the ultimate constraint on your desire to choose everything.

- Talk to the unusual suspects. These could be inside or outside your project, but whoever they are, choose them because they are likely to disagree with you, challenge you, or tell you something you do not know. To ensure you have a ready supply of such people, you may need to look again at your strategic network – it may have gotten too stale to offer you such connections. If that is the case, weed out the deadwood and actively recruit people from different sectors, skill sets, and backgrounds who can help you test the quality of your macro answers. Questions to ask them include: ‘Why will this not work?’ and ‘What do I have to believe for this not to turn out that way?’ Being challenged and having new information may well change your answers; even if it does not, it will make your existing answers more robust.

By following these simple mindful steps, we increase the project sensitivity beyond our immediate responsibilities (to be task-focused), enabling and requiring others to see beyond the short-term demands of project delivery and keep in mind what defines value in the project. This is a critical, driving focus that demands a desire to stay alert about uncertainty. It is central to retain the perspective of the Big Picture.

Being optimistic in the face of the abyss

It is, of course, vital that we as project leaders stress the potentially imminent nature of uncertainty arising. The project leader must play devil’s advocate to inject a dose of the reality of the future unknown to counter over-optimism and curb excessive enthusiasm. Although all this is important if uncertainty is to be meaningfully understood and interpreted within projects, it also poses the danger that the project team may become disheartened and demoralised by a continual preoccupation with adversity. We may feel disempowered in the face of seemingly insurmountable uncertainty where there are no clear resolutions, only half-solutions that satisfy no one. There is a further danger that we may feel nothing we can do will ever allow them to overcome the ever-present uncertainty and that all their effort is pointless. Therefore, another role of us is to guard against a sense of impending fatalism and apathy. The team must be reminded that they are being given capabilities for resilient working in an uncertain and complex environment.

Allowing people to appreciate different perspectives

Perhaps one of the most prominent early challenges for a project is to find a means of including and capturing the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. This is, of course, entirely dependent on the precise nature of the project being undertaken, but stakeholders rarely speak with one voice, even where they might represent a single organisation. How is the project team to capture and balance the different views of these multiple stakeholders? The project team may well find that these perspectives can be at odds with each other, which risks damaging the project. This is why value-driven project risk management is so important in such a situation. Our role here is to provide the space to make sense of the multiple perspectives at play.

Be careful, though. It is not sufficient to approach these potentially divergent opinions with a view to averaging and normalising them. If we reduce the richness of different perspectives to a single view, a single expectation, a single estimate, we may oversimplify. The abundance of different angles may be captured and used to understand better the nuances of the project so that pragmatic and context-specific solutions can be crafted and shared. Let’s appreciate therichness in multiple perspectives without losing sight of the common goal.

Perhaps the most useful starting point is for people to question their own assumptions. This could be done by having a conversation with a cynical colleague or even a person in another organisation – a ‘critical friend’ who can write down what they think your assumptions are and then confront you with them.

The tendency to overestimate the extent to which people agree with us is a cognitive bias known at the false consensus effect, first identified by Ross and sometimes called Ross’ False Consensus Effect (Ross et al. 1977). This agreement could take the form on other peoples’ beliefs, values, characteristics, or behaviour. For example, someone with extreme political views might erroneously believe that their views are much more widely held than they are. This might be exacerbated by social media were an algorithm to curate those views with other, similar views giving the person the impression that their opinions and views are widely held. It is thought that the false consensus effect arises because people regard their own views and opinions as normative. Another reason people might be influenced by the false consensus effect is that they tend to generalise from limited case evidence, with their own ideas and views being a data point (Alicke and Largo 1995), known as the availability heuristic.

There are many reasons underpinning the false consensus effect. The first is a self-serving bias – people want to believe their views and opinions are reasonable and prevalent, so they project their opinions on others (Oostrom et al. 2017). Second, our friends, family and colleagues – the people we interact with most often – are likely to be similar to us and share many of our beliefs and opinions, known as selective exposure. Another reason is the result of the egocentric bias – that people see things mostly from their own perspective and so struggle to see things from other peoples’ points of view. This can be seen as an anchoring-and-adjustment problem, which leads to the assumed similarity of perspectives. Finally, when context is essential, this exacerbates the false consensus effect. A form of attributional bias, this commonly can be seen where people feel their views are supported by external factors, even where such factors might be aberrant (Gilovich et al. 1983).

Just as people experience the false consensus effect in everyday life, so too do they experience it in organisational life. Typically, the result is prevalent in marketing and promotional contexts. People assume that consumers and other customers will view a product or service in the same way they do. When the product or service is then launched, they are surprised when the market does not respond in the way they expected. The same effect can often be seen in financial analysis and forecasts of future earnings of organisations (Williams 2013).

Semmelweis reflex

An interesting cognitive bias is the Semmelweis reflex (sometimes referred to as the Semmelweis effect). It is a propensity of people to reject new ideas or knowledge that contradict prevailing, accepted beliefs and norms. The term refers to the failed efforts of a Hungarian physician, Ignaz Semmelweis, to persuade his colleagues to adopt handwashing as a way of reducing childbed mortality rates. His colleagues experienced a kind of cognitive dissonance and, despite the evidence to the contrary, could not see the benefits of changing their existing practices. While the truth of this story is disputed (or, at least, nuanced) the effect is, nonetheless, a real one.

As with all cognitive biases, the Semmelweis effect can be found in all aspects of daily life, representing inertia to change ingrained habits and behaviours, even when these habits and behaviours are detrimental either to people’s own well-being or that of society at large. A good example is people’s refusal to accept the evidence of climate change and the need to change their behaviour to combat it.

Within the world of organisations, the Semmelweis reflex can also be found at play. This is often the case where there is an evidenced need for change, but people within the organisation refuse to accept that this is the case. For example, if a once-successful product is failing in the market place and market research suggests there is a problem with the packaging, the Semmelweis reflex might lead managers to reject this evidence out-of-hand and look for an alternative explanation as the packaging was once famous.

Extending the half-life of uncertainty

Where project amnesia is present, the experience of uncertainty may quickly fade. This fading can be thought of as the half-life of project learning. We are obligated to extend such memory for as long as possible. In the prolonged absence of failure, and with changes in personnel, this half-life can be remarkably short. Our role in this situation is to employ approaches to prompt memory and retain focus on the possibility of failure, mainly where success has been the norm for a protracted period. Refreshing people’s memory of the past while incentivising people to continuously look beyond the risk horizon might seem arduous and detract from the ‘actual’ work but, without it, patterns of response may be lost over time.

The impact of interpreting on relationships

A large number of people have only a limited appetite for uncertainty. This is not necessarily good news for our projects. Stakeholders such as funders, sponsors, and end-users all crave for certainty. They want to realise the benefits as soon as possible with a set-out investment of resources. It is incumbent on us not only to demonstrate competence in understanding and being prepared for this but also to disabuse stakeholders of the notion that any project is without such uncertainty, in particular, epistemic uncertainty. It is through this understanding that they will be more able to focus on and draw value from the project. It can be a confusing message to convey, and individuals may not wish to hear it but, if the stakeholders are to avoid delusions of success, it is in their collective interests to engage with this message.

Be reluctant to commit to singularity

Be aware of estimates turning into commitments. If we think about single estimates, we put an ‘anchor’ in the ground; we expect that estimate to materialise. It is important that uncertainty in estimates is brought to the surface. For example, an estimate can be given with a corresponding confidence level and the use of upper and lower bounds. It is also down to the language that is used to express uncertainty in our predictions. The simple use of ‘may’ and ‘might’ provides a necessary – although inconvenient – signpost to stakeholders that project planning is still a look into an unknown future.

Whether the project team is relying on single-point or range-bound estimates, it is essential to note that they are still just estimates. They should not be confused with commitments or constraints, and they should be used with that in mind. Unless this distinction is clear, the results could be painful. This, however, does not mean that estimators can throw caution to the wind and produce completely unreliable numbers. Things to look out for when reporting estimates to a broader stakeholder community are:

- Padded estimates – it is tempting to pad and buffer estimates through building in contingencies and assumptions. Sometimes, this is an appropriate procedure, but in general, it is to be avoided. All it does is create distrust in the overall reliability of the estimates which are, in turn, compromised.

- Failing to revisit estimates – just as the project team should revisit and reassess risk analyses, so too they should continually revisit and reassess estimates. As more information becomes available, so the assumptions and contingencies built into the estimate become more natural to assign.

- Avoid taking estimates at their face value – we tend to be over-optimistic and -confident with our forecasts. It is one of the jobs to find ways of validating and reconciling these estimates before using them as a source for planning or any other decision-making. This is where the role of the devil’s advocate or ‘critical friend’ is important, particularly in tandem with a focus on value.

- Avoid ignoring task dependencies – projects are considered as systems with tasks and activities that have complex interrelationships both within the project and with external systems. These interdependencies introduce uncertainty.

- Communication of estimates – a great deal is at stake in the communication of the estimates. They require the buy-in of influential stakeholders but must also be communicated in such a way that they do not encourage a false certainty.

- Be wary of silos – estimating is not a single person’s responsibility, although one individual may be responsible for consolidating and communicating the estimates. Estimating is improved by getting consensus and broader understanding about what we do think we know and what remains unknown, and the more involved the team members are in gathering and discussing the estimates, the richer foresight becomes.

Selling capabilities to deal with uncertainty, not the illusion of certainty

We are often held up as paragons of planning who can bring control to what might otherwise be chaos. We may come armed with a plethora of techniques and processes, with an idea to instil confidence in stakeholders that we will succeed through careful planning. Perhaps understandably, given the desire for certainty, we may downplay the role of uncertainty in projects. However, it gives a false impression that uncertainty is somehow ‘tameable’ and can be significantly reduced or even eradicated. Rather than starting on this footing, it might be more useful to form relationships with the stakeholders that acknowledge that uncertainty is ever-present and that the real capability of the project team is to be resilient. In part, this is done through careful planning and control, but it mainly draws on the capabilities of mindful project management. A chief part of this approach is the ability to understand and make sense of uncertainty.

Understanding and appreciating multiple perspectives

Multiple stakeholders bring with them various perspectives of what the project means to them and, moreover, these perspectives are liable to change as the project progresses. Value-driven project management offers some techniques that can be used to find and make sense of the value that stakeholders wish to derive from the project. However, this cannot be just a one-off exercise undertaken at the beginning of a project to allow it to proceed. Just as perspectives of value are relational, contextual, and dynamic, so are the attendant uncertainties. If the project team is seeking to understand and meaningfully interpret uncertainty in the project, it needs to be continually attending to the multiple perspectives stakeholders will bring. In this way, it can track and grasp the changing nature of uncertainty as it unfolds through the life of the work.

Deepwater horizon – a failure of interpreting

On 20 April 2010, officials of British Petroleum (BP) visited the Deepwater Horizon rig, owned by Transocean and contracted out to BP, and presented the crew with an award for seven years of operating without any personal injuries. On the very same day, at 21:45, high-pressure methane gas expanded up to the wellbore and ignited on the drilling deck, killing 11 workers. The rig sank two days later, resulting in an oil spill and causing the worst environmental disaster in US history.

Deepwater drilling combines a range of challenges such as drilling at depths of up to 3000 m, shut-in pressures of 690 bars, or problematic ground formations. The Deepwater Horizon rig was a 5th generation drilling rig, outfitted with modern drilling technology and control systems. In 2002, it was upgraded with an advanced system of drill monitoring and troubleshooting, including automated shutoff systems.

At the time of the accident, in April 2010, Deepwater Horizon was drilling an exploratory well at the Macondo Prospect. In the wake of the disaster, poorly written emergency procedures and lack of situational awareness were identified as contributing factors. In this respect, a practice called ‘inhibiting’ was scrutinised.

Inhibit functions are designed to prevent the presentation of warning signals that are deemed inappropriate or unnecessary. In this case, audio or visual warnings could be manually suppressed if an alert was seen as providing unnecessary information or distracting an operator. At Deepwater Horizon, the rig’s chief technician, Mike Willaims, observed a culture of inhibiting, whereby control systems are bypassed or, even, shut down. Williams mentioned to investigators:

In the light of cost pressures, the persistence of false alarms combined with the perception of alarms as a nuisance meant that control systems were gradually ‘inhibited’; thus, warning signals suppressed and ignored. The rig warning systems tried to alert the operators that a disaster was looming but the alarms went unnoticed.

In project-like work such as deepwater drilling, such technical control systems may well exist, although, in most projects the control system is composed of human beings. If people suffer from optimism bias, effects of normalisation, and reduce the realm of probability to ‘It will not happen to me, or will not affect me’, then we interpret important warning signals of an impending crisis as just noise that can be easily ignored.

The mindful management of epistemic uncertainty requires scrutiny and scepticism; to take nothing for granted. The focus should be to assume that each signal of failure is an indicator of a more systemic problem that if untreated will cascade into a crisis. A form of discomfort to question, challenge, and scrutinise is of the essence to interpret epistemic uncertainty appropriately.

Towards an art of interpreting

The realistic interpretation of uncertainty is constrained by our longing for simplicity and certainty. We often break down an uncertain environment into its parts and look at them in isolation; such thinking is amplified by our tendency to underestimate the impact of uncertainty, and to overestimate our capabilities to deal with it. There is help, though. Our desire to make sense of the future through simplification should not be replaced altogether, but it should be challenged. Deploying practices such as a devil’s advocate may start us on a journey that challenges our inclination to oversimplify, to interpret a project just within the boundaries of the risk horizon.

Reflection

How well do the following statements characterise your project? For each item, select one box only that best reflects your conclusion.

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| We are reluctant to use single-point estimates. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We are challenged in our optimism. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We analyse interdependencies between risks and uncertainties. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| We appreciate uncertainty beyond the risk horizon. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We are constantly directed by our value-driven ‘big picture’. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We appreciate that traditional planning tools may amplify oversimplification. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Fully disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Fully agree | |||

| We apply practices such as Devil’s Advocate. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We envisage multiple futures or scenarios. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We convey to our stakeholders that our project is neither certain nor simple. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Scoring: Add the numbers. If you score higher than 27, your capability to interpret uncertainty beyond the risk horizon is well developed. If you score 27 or lower, please think about whether you have created an illusion of certainty and control.

References

Alicke, M. D., and E. Largo. 1995. “The Role of Self in the False Consensus Effect.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 31(1): 28–47.

Arkes, H. R., and C. Blumer. 1985. “The Psychology of Sunk Cost.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35(1): 124–401.

Carreyrou, J. 2018. Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, by John Carreyrou | Financial Times. Financial Times. London: Picador.

Flyvjberg, B. 2005. “Design by Deception: The Politics of Megaproject Approval.” Harvard Design Magazine 22: 50–59.

Gilovich, T., D. L. Jennings, and S. Jennings. 1983. “Causal Focus and Estimates of Consensus: An Examination of the False-Consensus Effect.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45(3): 550–595.

Healy, P. 2016. “Over-Confidence: How It Affects Your Organization and How to Overcome It.” Harvard Business Review Online. 2016. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/over-confidence-how-it-affects-your-organization-and-how-to-overcome-it.

Herzog, S., and R. Hertwig. 2009. “The Wisdom of Many in One Mind: Improving Individual Judgments with Dialectical Bootstrapping.” Psychological Science 20(2): 231–372.

Hogarth, R. M. 1978. “A Note on Aggregating Opinions.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 21(1): 40–46.

Kahneman, D., and D. Lovallo. 2003. “Delusions of Success: How Optimism Undermines Executives’ Decisions.” Harvard Business Review 81(7): 56–63.

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1991. “Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(4): 1039–61.

Kutsch, E., H. Maylor, B. Weyer, and J. Lupson. 2011. “Performers, Trackers, Lemmings and the Lost: Sustained False Optimism in Forecasting Project Outcomes – Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment.” International Journal of Project Management 29(8): 1070–81.

Levine, R. 2006. The Power of Persuasion: How We’re Bought and Sold. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Moore, D., A. Carter, and H. Yang. 2015. “Wide of the Mark: Evidence on the Underlying Causes of Overprecision in Judgment.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 131: 110–201.

Moore, D., and P. Healy. 2008. “The Trouble with Overconfidence.” Psychological Review 115(2): 502–175. www.mendeley.com/research/the-trouble-with-overconfidence/.

Oostrom, J. K., N. C. Köbis, R. Ronay, and M. Cremers. 2017. “False Consensus in Situational Judgment Tests: What Would Others Do?” Journal of Research in Personality 71: 33–45.

Pallier, G., R. Wilkinson, V. Danthiir, S. Kleitman, G. Knezevic, L. Stankov, and R. D. Roberts. 2002. “The Role of Individual Differences in the Accuracy of Confidence Judgments.” Journal of General Psychology 129(3): 257–992.

Rick, S. 2011. “Losses, Gains, and Brains: Neuroeconomics Can Help to Answer Open Questions about Loss Aversion.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 21(4): 453–634.

Rong-Gong, Lin. 2010. “Alarms, Detectors Disabled so Top Rig Officials Could Sleep.” Los Angeles Times. 2010. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-jul-23-la-oil-spill-disabled-alarms-20100723-story.html.

Ross, L., D. Greene, and P. House. 1977. “The ‘False Consensus Effect’: An Egocentric Bias in Social Perception and Attribution Processes.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 13(3): 279–301.

Ryan, S. 2016. “How Loss Aversion and Conformity Threaten Organizational Change.” Harvard Business Review Digital Articles 2–5. 25 November 2016.

Schindler, S., and S. Pfattheicher. 2017. “The Frame of the Game: Loss-Framing Increases Dishonest Behavior.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 69: 172–771.

Shah, P., J. L. Adam, G. B. Harris, C. Catmur, and U. Hahn. 2016. “A Pessimistic View of Optimistic Belief Updating.” Cognitive Psychology 90: 71–127.

Sharot, T. 2016. The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain. New York: Pantheon Books.

Sugden, R., J. Zheng, and D. J. Zizzo. 2013. “Not All Anchors Are Created Equal.” Journal of Economic Psychology 39: 21–31.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185: 1124–31.

Weinstein, N. 1980. “Unrealistic Optimism about Future Life Events.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39(5): 806–208.

Williams, J. 2013. “Financial Analysts and the False.” Journal of Accounting Research 51(4): 855–907.

Yaniv, I., and D. P. Foster. 1995. “Graininess of Judgment under Uncertainty: An Accuracy-Informativeness Trade-Off.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 124(4): 424–324.