Audience Research in Programming

To give value to commercial time, the electronic media must attract audiences. Broadly speaking, that is the job of a programmer, who may be anyone from the president of a huge media conglomerate to someone working for a radio station in a small rural community. In the world of advertiser-supported media, the programmer effectively sets the “bait” that lures the audience. In order to do this, he or she must know a great deal about audiences; after sales and advertising, the most important application of audience data is in programming.

Programming involves a range of activities. A programmer must determine where to obtain the most appropriate programs. Sometimes that means playing an active role in developing new program concepts and commissioning the production of pilots. For most television stations, it means securing the rights to syndicated programs, some of which have already been produced. In this capacity, the programmer must be skillful in negotiating contracts and in predicting the kinds of material that will appeal to prospective audiences. Programmers are also responsible for deciding how and when that material will actually air on the station or network. Successful scheduling requires knowing when different kinds of audiences are likely to be available, and how those audiences might decide among the options offered by competing media. Finally, a programmer must be adept at promoting programs. Sometimes that involves placing advertisements and promotional spots to alert the audience to a particular program or personality. With the growth of social media, it can mean promoting favorable word-of-mouth, triggering information cascades, although these are notoriously difficult to manage. It can also involve packaging an entire schedule of programs in order to create a special station or network “image.” In all of these activities, ratings play an important role.

The way in which these programming functions take shape, and the priorities facing individual programmers, differs from one setting to the next. Occasionally, in small stations, the entire job of programming falls on the shoulders of one person. In larger operations, however, programming involves many people. Often the job of promoting programs and developing an image is turned over to specialized promotions departments, especially in an increasingly competitive media marketplace.

The most significant differences in how programmers function depend on the medium in which they work. In the early 1950s, television forced radio to adapt to a new marketplace. No longer would individual radio programs dominate the medium. Instead, radio stations began to specialize in certain kinds of music or in continuous program formats. The job of a radio programmer became one of crafting an entire program service. Further, the vast supply of music from the record industry meant that stations could be less reliant on networks to define that service. In contrast, television built audiences by attracting them to individual programs. Although some cable networks now emulate radio by offering a steady schedule of one program type (e.g., news, music, weather, financial and business information, or comedy), most television programmers still devote more attention to the acquisition, scheduling, and promotion of relatively distinct units of content.

In the case of broadcast network affiliates, most program development and acquisition is done at the network level. However, affiliated stations do program certain dayparts, such as news, early fringe, and late night. There are also some independent television stations that program the entire broadcast day. In order to explain how audience research is used in programming, we consider the specific programming practices of each form of electronic media.

Although facing increased competition from evolving audio technologies, traditional radio is still a significant medium in the United States. Arbitron estimates that radio reaches 93 percent of all persons aged 12+ in the course of an average week. There are more than 13,000 commercial radio stations in the United States and another 2,500 noncommercial educational ones, each offering different—sometimes only slightly different—programming and each reaching unique audiences. Most radio stations, from the smallest to the largest markets, have a format. A format is an identifiable set of program presentations or style of programming. Some stations, particularly those in smaller markets with fewer competitors, may have wider ranging formats that try to include a little something for everyone. Most stations, however, zero in on a fairly specific brand of talk or music.

Radio stations use formats for two related reasons. First, radio tends to be very competitive. In any given market, there are far more radio stations than television stations, daily newspapers, or almost any other local advertising medium. To avoid being lost in the shuffle, programmers use formats to make their station seem unique or special so it will stand out in the minds of listeners and induce them to tune in. This strategy is called positioning the station. Second, different formats are known to appeal to different kinds of listeners. Because most advertisers want to reach particular kinds of audiences, the ability to deliver on a certain demographic is important in selling the station’s time.

Radio formats run the gamut from classical to country to pop contemporary hits. Radio programmers, consultants, and analysts have fairly specific names for dozens of different formats. However, most of these are usually grouped in about 20 categories. The most common labels, ranked by weekly cume, are shown in Table 8.1.

Format popularity varies by listener demographics, including age, gender, and ethnicity. For example, women listen to more adult contemporary and religious stations than men do; and men are more likely to listen to sports and album-oriented rock. While country is popular across all age groups, older adults prefer news/talk and information and adult contemporary; and young adults and teenagers consume more pop contemporary hit radio. Comparing the ethnic composition of audiences for radio, urban adult contemporary and urban contemporary are the formats ranking high with African Americans; Spanish adult hits, Mexican regional, and Spanish contemporary rank highest with Hispanics. There are different ways to program a radio station. Some stations do all of their own programming. They identify the specific songs they will play, and how often they will play them. They may also hire highly visible—and highly paid—disc jockeys, who can dominate the personality of the station during certain dayparts. This kind of customized programming is particularly common in major markets, and it is often accompanied by customized research. Not only do these stations buy and analyze syndicated ratings, they are also likely to engage in a variety of nonratings research projects.

The most typical nonratings research includes focus groups, which feature intensive discussions with small groups of listeners, and call-out research which involves playing a short excerpt of a song over the telephone to gauge listener reactions. Consultants also conduct customized research to investigate how radio audiences react to potentially offensive material, to assess listener awareness of particular program services, to measure the impact of advertising (for example, on bus cards, billboards, or television spots), and to judge the popularity of particular personalities or features (news, traffic, weather, contests, etc.) on the station.

Many stations, however, depend on a syndicated program service or network to define their format. Sometimes, large group owners like Clear Channel and Cumulus provide programming to their stations on a regional or format basis. Some stations rely on prepackaged material for virtually everything they broadcast, except local advertising and announcements. To do this they subscribe to a program service, usually provided to the station by a satellite feed. Other stations do some of their own original programming during the most listened-to morning hours and use syndicated services during the remaining hours of the day.

TABLE 8.1

Radio Station Formats Ranked by Weekly Cume

Note: Due to rounding, totals of gender composition percentages may not add to 100.

Source: Format definitions are supplied to Arbitron by the radio stations. Data come from TAPSCATM Web National Regional Database. Fall 2010.

Source: Arbitron Radio Today, 2011. Reprinted by permission of Arbitron.

Most radio stations do not worry about ratings research because the majority are located in small to very small communities. Arbitron defines and measures radio listening in more than 270 market areas, the smallest with a population of less than 80,000. Even at that, the company publishes audience estimates for only about one third of the nation’s more than 13,000 radio stations. Of course, measured stations account for the vast majority of the industry’s listening and the lion’s share of its revenues.

Noncommercial radio outlets also use quantitative audience estimates. National Public Radio (NPR) stations, for example, receive ratings, even though they are not listed in the ratings book alongside their commercial counterparts. In some markets they are even among the highest rated local stations. While audience data are not used in quite the same way, they may be important for fund-raising. Many of the larger stations have the functional equivalent of a sales department that regularly uses audience estimates to attract underwriting. Ratings are also used by programmers to make many of the same decisions a commercial station does about program popularity, scheduling, and promotion.

One of the most significant changes in radio audience measurement came with the introduction of PPMs in 2010. Although the majority of radio markets are still measured with diaries, close to 50 of the largest ones now receive estimates based on the PPM.

Traditional radio now competes with online audio and with satellite radio. According to the Pew Research Center (2012), roughly a third of Americans are listening to online audio services (including streaming AM/FM stations). And, although SiriusXM radio does not yet provide appreciable competition in any single radio market, some industry experts think satellite radio will impact the industry the way FM affected AM or the way cable affected broadcast television. In 2011, satellite radio had 22 million subscribers (Pew Research Center, 2012). Carmakers are installing satellite receivers as standard or optional equipment, and the acquisition of several important radio personalities, including Howard Stern, along with the ability to provide local market traffic and weather information, could lead to large subscription increases over the next few years.

Broadcast

At the other end of the spectrum is the business of programming a major television network. Although television programmers share some of the same concerns as radio programmers, they are confronted with a number of different tasks. One important difference is the extent to which a network programmer is involved in the creation of new programs. Ratings data are certainly valuable for this task, but program development relies especially on talents for anticipating popular trends and tastes, and setting in motion productions that will cater to those tastes. Network programmers who have that talent are as well known in the business as any on-screen celebrity.

The studios, whose job it is to finance and produce programs and sell them to the networks, also rely on ratings information. The premiere of a show gives a snapshot, but the subsequent few weeks are really critical for the show’s future. In order to convince networks to keep a show on the air, studio research departments study the ratings from different angles to look for signs that a show is trending upward. A decline in ratings might mean cancellation, but it could also motivate adjustments to program content. Programmers might request changes in program elements such as casting, storylines, or character development if they think these changes will increase viewership.

Programmers at local television stations spend less time on the actual production of new programs, and more time on purchasing them in the syndication market. Several kinds of syndicated programs are available, and new ones enter the pipeline every season. Off-network syndicated programs are those that originally aired on a broadcast network and are now available to individual stations. In general, they are among the most desirable of all syndicated programming from the standpoint of ratings potential.

Off-network programs work well in syndication for a number of reasons. They typically have high production values—something that viewers brought up on network fare have come to expect. They also have a track record of drawing audiences, which can be reassuring for the prospective buyer. In fact, only network series that have been on-air for at least 4 or 5 years usually make it to syndication. One reason for this is that local programmers schedule reruns as strips, airing different episodes Monday through Friday at the same time of day. To sustain stripped programming over several months, they must own a good number of programs. In general, this means that there must be 100 episodes before a series is viable in syndication; only the most popular network shows stay on the air that long.

Once they reach syndication, however, off-network programs can continue to attract new audiences for decades. M*A*S*H, for example, was enormously successful on CBS when it aired in the 1970s, and it has been successful in syndication for more than 30 years. Newer off-network programs, some available even before their original run ends, get the most desirable time slots, while older series get displaced to less desirable times. Nevertheless, with so many stations and cable outlets with so many hours to fill, even older programs, especially those that were very popular or have semi-cult status, still seem to find an audience. The durability of off-network series means they have an extensive ratings history, which is especially useful in programming. Prospective buyers can compile detailed information from many different markets, analyzing the relative success of one program versus another, or the flow of audience from one program to and from another.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, networks started to rely on reality programs like Survivor, American Idol, and The Voice. These unscripted shows affect the syndication market by decreasing the number of off-network series that can draw audiences in syndication. Unlike scripted comedies and dramas, reality programs do not attract large audiences when they are repeated. After all, the fun of reality programs is to find out who wins—once that is known, audiences lose interest in viewing the series.

Syndication has also been affected by the trend toward vertical and horizontal integration in the media industries. A single owner can now have substantial financial interest in the production of programs, their distribution through syndication, and the stations or cable networks to which they can be sold. In the case of broadcast syndication, this means first priority will usually be given to the co-owned stations. In turn, these stations will usually comply with the seller’s scheduling requirements. This situation presents a challenge for stations that have to find new sources of programming, and for independent syndicators who have to fight for fewer available time slots.

In recent years, cable has become a significant player in the syndication market. Some cable networks depend almost exclusively on reruns of old programs. Others complement their schedule of new programs and films with vintage series that are likely to appeal to specific target audiences. Mystery fans can watch Perry Mason on the Hallmark Channel or Murder, She Wrote on A&E. Saturday Night Live fans can watch reruns on Comedy Central, and science fiction fans can watch the earliest episodes of The Twilight Zone on the Sci Fi channel. An off-cable syndication market has also emerged, with pay cable series like The Sopranos and Sex and the City finding homes on basic cable networks.

Some programs are produced directly for syndication. Traditionally, these “first-run” syndication programs have included game shows and talk shows that cost relatively little to produce. More recently, courtroom reality series like Judge Judy have become very successful in first-run syndication.

There are other sources of programming, like movie packages or regional networks, but whatever their origin, the acquisition of syndicated programming is one of the toughest challenges a television programmer has to face. Usually the deal involves making a long-term contractual agreement with the distributor, or whoever holds the copyright to the material. For a popular program, that can mean a major commitment of resources. A mistake can cost an organization millions of dollars, and the programmer a job.

Buying and selling syndicated programming is often accompanied by an extensive use of ratings data. Distributors use the ratings to promote their product, demonstrating how well it has done in different markets. These data are often prominently featured in trade magazine advertisements. Buyers use the same sort of data to determine how well a show might do in their market, comparing the cost of acquisition to potential revenues. This is discussed in greater detail in chapter 9.

Once a network or a station commits to program production or acquisition, television programmers at all levels have more or less the same responsibility. Their programs must be placed in the schedule so as to achieve their greatest economic return. Usually that means trying to maximize each program’s audience, taking into consideration the competition each show faces in the market. For affiliates, the job of program scheduling is less extensive than for others, simply because their network assumes the burden for much of the broadcast day. Even affiliates, though, devote considerable attention to programming before, during, and just after the early local news. The prime access daypart, just before network prime time, is usually very lucrative for an affiliate. Audience levels rise through the evening and the station need not share the available commercial spots with its network.

In television, as in radio, program production companies, network executives, and stations use a variety of nonratings research to sharpen their programming decisions. This may include the use of one or more measures of program or personality popularity. Marketing Evaluations, for example, produces a syndicated research service called TVQ that provides reports on the extent to which the public recognizes and likes different personalities and programs. Scores like these can be used by programmers when they make scheduling decisions. Knowing the appeal of particular personalities might tell them, for example, whether a talk show host would fare well against the competition in a fringe daypart.

Increasingly, the chatter or buzz on social media is being turned into metrics that help guide program decision-making. For example, a company called Bluefin Labs collects the comments people make on Twitter and other social networks. These are tied to particular programs and aggregated to create measures of engagement. Those measures are not always correlated ratings (i.e., popular programs are not always the most talked about). In some instances, analysts can judge whether comments are positive or negative and determine the gender of the persons making those comments. Optimedia, a major media buyer, combines such measures of buzz with convention ratings to create what it calls “content power ratings.”

Other program-related research includes theater testing, which involves showing a large group a pilot and recording their professed enjoyment with voting devices of some sort. All networks and most program producers use some type of testing research in the program production process. One of the largest program testing facilities is in Las Vegas. Strange as it may seem, researchers recruit audiences—between the swimming pool and the lobby—of a large hotel. Pilots, commercials, and other program material are shown while respondents, seated at a computer, record data about themselves and give periodic reactions to the material being shown. This method, which identifies individual and cumulative responses to program elements, traces its origins back to the original Stanton–Lazarsfeld Program Analyzer of the late 1930s. Program executives can see this information almost instantly on their office computers in Los Angeles, New York, or anywhere. Ultimately, however, ratings are a programmer’s most important evaluative tool. A classic quote from a network executive sums this up nicely, “Strictly from the network’s point of view a good soap opera is one that has a high rating and share, a bad one is one that does not” (Converse, 1974).

As we implied previously, programming for some cable networks is similar to radio, and for others it is more like over-the-air television. Cable networks like WGN and TBS, for example, began as local stations and became national super stations by distributing their service via satellite. These and others like them often include a variety of programs in their lineups, much like television stations. The major difference between cable and local television though is that cable programmers seek more narrowly targeted audiences than do television broadcasters. Lifetime is programmed for women; ESPN and Spike for men; and the Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon for children. Some cable services concentrate on one type of content, such as news, talk, travel, cooking, and weather. You’ll often find, however, that even specialized services use some variety of formats to broaden their audience. For example, virtually all have tried different forms of documentary programming as part of their schedule.

Programming strategies can be visualized on a continuum from traditional broadcast scheduling to newer forms of cable or narrowcasting. While programming patterns for each service have remained relatively distinct throughout most of television’s history, some programmers are now testing alternative approaches. Broadcasters, for example, are using programming models that originated on public television or cable, such as repeating popular programs within the same week. Some original network programs are repeated on cable channels, usually co-owned networks, soon after their first run. To further complicate the situation, the growing ability of viewers to build their own schedules with various recording and on-demand technologies is likely to change the role of the programmer altogether. Although services like HBO and Showtime do not need audience estimates to sell advertising, pay cable ratings are still a valuable commodity. High ratings generate interest from media critics, analysts of pop culture, journalists, potential subscribers, and, importantly, media outlets interested in purchasing off-cable syndication rights. When pay cable series like The Sopranos earn higher ratings than some broadcast competitors, they attract the attention of Hollywood and Wall Street. Successful production efforts generate revenue for re-investment into new programming.

Pay cable’s business model depends on recruiting at least one subscriber in a household and convincing him or her to renew a subscription year after year. Programmers maintain the quality of the schedule by offering theatrical movies, often before anyone else has the rights. They are able to secure this early window by making long-term deals with various studios. They also use promotional campaigns to create demand for, and buzz about, the channel’s original programming. HBO’s yearly Emmy nominations certainly prove how well they have succeeded on this front.

As cable channels, from basic to premium, gain popularity and take ratings away from commercial networks, broadcasters complain that the playing field is uneven. Due to differences in regulation and societal expectations, cable is able to address themes that are banned from over-the-air television. In fact, “edgy” content on cable networks usually means more sex and violence than on broadcast television.

As we saw in the previous chapter, the Internet has created new opportunities for advertisers to reach audiences. This means the content of Web pages has become increasingly important. “Programming” on the Web can mean anything from the simplest personal Web page to the most sophisticated corporate sites, to multimedia programs that viewers watch on their computer, tablet, mobile, and television screens. For many radio stations it means making the station available to a much wider audience. Most television networks make programs available on the Internet the day after their original broadcast—along with older programs they hope will capture the viewer’s attention.

Sites like Hulu and Netflix gained popularity by streaming licensed videos to subscribers. Both services began making deals for original programming in the early 2010s, which put them in direct competition with traditional media outlets, especially pay cable. Netflix plans new episodes of Arrested Development, and the company outbid HBO and AMC for the right to produce House of Cards. Hulu began offering original series like Battleground and Spoilers in 2012. Whether the production of new programs develops into full-fledged competition with traditional media outlets remains to be seen.

Just like the more traditional electronic media, Internet content must be planned to attract audiences in the first place and to hold their attention. Research suggests that Internet users build a set of favorite Web resources, just as radio listeners and cable television viewers develop a set of favorite channels that they watch repeatedly. There are a few major differences, though. Content on the Web can be personalized in a way that was never before possible. If users allow cookies to be stored on their computers, a programmer could theoretically serve very individualized messages—a capability that interests Web advertisers. There is also an immediate feedback mechanism with the Internet that allows programmers and producers to interact with viewers.

The relationship between the more traditional electronic media and the Web continues to evolve. Broadcast networks and stations maintain Web sites that offer additional services to the viewers they already reach over the air, and to new viewers who make initial contact via the Web. They often provide advertising availabilities on these sites to enhance the value of broadcast advertising. Networks have experimented with showing trailers for films on their websites, an option that media buyers for the studios find attractive.

In whatever way the Internet evolves, and whatever connections form between old media and new, the need for audience information is certain. Programmers need ratings-type data to track the most popular sites and determine the services most valued by particular audiences.

Many of the research questions that a programmer tries to answer with ratings data are, at least superficially, no different than those asked by a person in sales and advertising: How many people are in the audience? Who are they? How often do the same people show up in the audience? This convergence of research questions is hardly surprising because the purpose of programming commercial media is, with some exceptions, to attract audiences that will be sold to advertisers. The programmer’s intent in asking these questions, however, is often very different. Programmers are less likely to see the audience as some abstract commodity, and more likely to view ratings as a window on what “their” audiences are doing. They need to understand not only the absolute size of a program audience, but why they are attracting particular audiences and what could be done to improve program performance.

Did I Attract the Intended Audience?

Because drawing an audience is the objective of a programmer, the most obvious use of ratings is to determine whether the objective has been achieved. In doing so, it is important to have a clear concept of the intended, or target, audience. Although any programmer would prefer an audience that is larger to one that is smaller, the often-quoted goal of “maximizing the audience” is usually an inadequate expression of a programmer’s objectives. More realistically, the goal is maximizing the size of the audience within certain constraints or parameters. The most important constraint has to do with the size of the available audience. That is one reason why programmers are particularly alert to audience shares. Increasingly, however, it is not the programmer’s intention to draw even a majority of the available audience. In other words, the programmer’s success or failure is best judged against the programming strategy being employed.

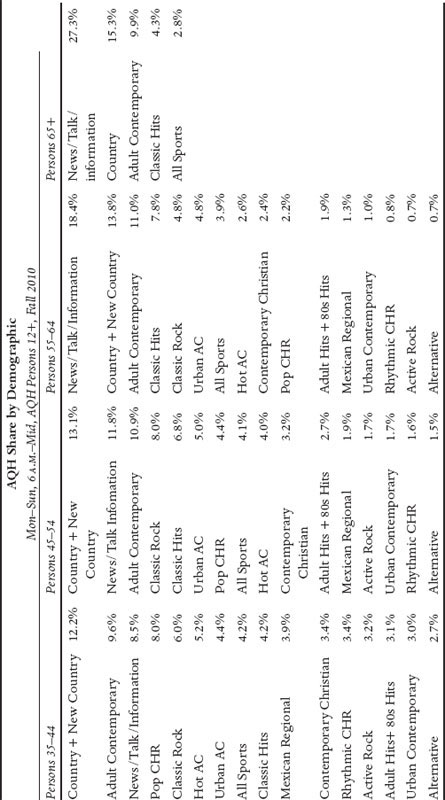

Radio programmers, and increasingly those at cable networks, are largely concerned with cultivating well-defined target audiences. An experienced radio programmer can fine-tune a station’s demographics with remarkable accuracy. Much of this has to do with the predictable appeal that a certain kind of music, and talk, has for listeners of different ages and gender. Table 8.2 lists some of the more common station formats and percent of their total audiences in different age categories. Obviously, you cannot expect to attract many young people with Oldies music, or many older listeners with Alternative rock.

Television programmers, like their counterparts in radio, may devote their entire program service to attracting a particular demographic. This is most evident in some of the highly specialized cable networks. MTV and Nickelodeon, for example, are programmed to draw certain age groups that their owners believe will be attractive to advertisers.

Even those conventional television stations that offer a variety of program types must gauge the size and composition of program audiences against the programming strategies they employ. One common strategy is called counter-programming. This occurs when a station or network schedules a program that has a markedly different appeal than the programs offered by its major competitors. For example, independents tend to show light entertainment (e.g., situation comedies) when the affiliates in the market are broadcasting their local news. The independents are not trying to appeal to the typical, often older, news viewer, and their ratings should be evaluated accordingly. Programmers may try counter-programming stunts to attract viewers who are not interested in the special events covered by other stations in the market. One station in Chicago, for example, broadcast a lineup of romantic dramas that it called “The Marriage Bowl” to compete with the college football games on New Year’s Day.

One way to increase the likelihood of attracting the intended audience is through the use of promotional spots. Ratings data can be very useful in identifying programs with similar demographic profiles so that promotional announcements appealing to a particular audience can be scheduled when members of that target group are watching.

Noncommercial media also care about attracting an audience. Public broadcasters in the United States, or public service broadcasters around the world for that matter, must ultimately justify their existence by serving an audience. This can only be done if an audience is identified and measured. Therefore, many public stations use ratings as well. National Public Radio (NPR), with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), has provided audience estimates to NPR stations since 1979. The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), which distributes much of the programming to noncommercial stations, subscribes to national ratings for several months of each year to judge the attractiveness of its programming. And many individual stations subscribe directly to Nielsen or indirectly through research consultants who analyze the data for them.

TABLE 8.2

Radio Station Formats by Age and Gender

Source: Arbitron Radio Today, 2011. Men and women include only listeners 12+ years old. Reprinted by permission of Arbitron.

Note: Top 16 formats listed.

Source: Format definitions are supplied to Arbitron by the radio stations. Data come from TAPSCANTM Web National Regional Database, Fall 2010.

Although they do not have sponsors in the traditional sense, public broadcasters care very much about reaching, even maximizing, their audiences. For one thing, many organizations that put up the money for programming are interested in who sees both their programs and the underwriting announcements. The more viewers there are, the happier the funding agency is. Further, public stations are heavily dependent on donations from viewers. Only those who are in the audience will hear the solicitation. Thus, many public television broadcasters pay considerable attention to their cumes and ratings.

Even if one has no funding concerns in mind, programmers in a public station well might ask a question like “How can I get maximum exposure for my documentary?” Often documentaries and “how-to” programs can earn the same or a higher rating when repeated during weekend daytime or late night than they do during the first run in prime time. A careful analysis of audience ratings data could reveal when the largest number of those in the target audience are available to view, or whether the intended audience really saw the program.

Like the concept of “engagement,” audience loyalty is difficult to define precisely because it means different things to different people. Typically, channel loyalty is the extent to which audience members stick with, or return to, a particular station, network, program, or website. Loyalty is something that manifests itself over time. Despite all the positive images the word connotes, we should point out that audience loyalty is quite different from audience size—the attribute most valued by time buyers. Programmers are interested in audience loyalty for a number of reasons. First, in the most general sense, it can give them a better feel for their audience and how they consume the programming that is offered to them. This knowledge can guide other scheduling decisions. Second, audience loyalty is closely related to advertising concepts like reach and frequency, so it may affect the way an audience is sold. Finally, it can provide an important clue about how to build and maintain the audience you do have, often through a more effective use of promotions.

Radio programmers use a number of simple manipulations of ratings data to assess audience loyalty. Although the heaviest radio listening is in the morning when people wake up and prepare for the day, listeners turn their radios on and off several times during the day. They also listen in their cars or at work. To maintain ratings levels, a radio station must get people to tune in as often as possible and to listen for as long as possible. Radio programmers use two related measures, time spent listening (TSL) and turnover, to monitor this behavior. Using a simple formula based on the average ratings and cume ratings that are in the radio book, one can compute TSL for any station in any daypart. Turnover is the ratio of cume audience to average audience, which is basically the reciprocal of TSL.

If you listen to just about any radio station you can hear how they try to keep you tuned in—naming the songs or other items coming up, running contests, and playing a certain number of songs without commercial interruption. To programmers, these tricks of the trade are for quarter-hour maintenance—that is, trying to keep listeners tuned in from one quarter-hour to the next. The 15-minute period is important, because it is the basic unit of time used to compute and report ratings in diary markets. By tracking TSL and audience turnover measures, the programmer can see how well the audience is being retained.

The importance of TSL varies according to the specific format of a station. All would like to keep their listeners tuned as long as possible—but that is more likely for stations with narrower, more specialized formats such as country, urban, Spanish, or religious—although these formats may share audience if there are several similar stations in the market.

Another common measure of loyalty in radio programming is called recycling. Because ratings books routinely report station audiences for morning and afternoon drive time combined, it is possible to determine how many people listened at both times. This can be a useful insight. If the number is relatively small, for example, stations may offer similar programming, or they may do more promotion.

The same basic research question is relevant to television programmers as well. Do the people who watch the early evening news on a particular station return to watch the late news? If the answer is no, especially if the early news is successful, it would make sense to promote the later newscast with the early news audience.

What Other Stations or Programs Does My Audience Use?

In some ways, this is just the opposite of the preceding question. Although there are some people who will listen to one, and only one, station, it is more common for audience members to change from one station to another. In radio, we noted that no two stations are programmed precisely alike or reach exactly the same audience, but several stations in a large market may have very similar, or complementary, formats. For example, listeners who are interested in news and information in the morning might prefer a more relaxing dose of “lite rock” on the drive home, and so use two different stations almost equally. Or, listeners might not like a so-called “shock jock” on the station in the morning but are attracted to another comic talker in the afternoon. Whatever the reasons, many people listen to at least two stations each day. Programmers know that many of their listeners hear four or five other stations in a week. Radio listeners may have favorite times for choosing different formats, for example, news in the morning or jazz at night. It is important for a programmer to be able to assess the use of other stations.

In the largest markets, a station may be one of 60 or more radio signals available to listeners. However, the important competitors for most programmers are the other stations trying to reach a similar target audience. These are likely to be stations with similar formats. In general, advertisers only buy one or two stations deep to reach the specific demographic target they seek most. Knowing as precisely as possible where your listeners spend the rest of their radio time is very important.

The use of ratings information and a few tabulations will enable a programmer to know all the other stations with which he or she shares listeners. Two types of information are most relevant. The first is the exclusive cume, or the number of people who listened to just one particular station during specific dayparts. Although this is actually a measure of station loyalty, when it is compared with the total cume, it reveals the proportion of a station’s audience that has also used the competition. That does not tell you which stations they are, however. This information is conveyed through a statistic called cume duplication, which reveals the extent to which the audience for one station also tunes to each of the other stations in the market.

While many listeners have a favorite station that they attend to most of the time, they may also try other stations with similar formats or try something completely different. That there is so much overlap among stations suggests that people have varied tastes and that they might like other fare during different times of the day or week. It is clear, however, that stations share the most listeners with stations of similar appeal.

To get a detailed look at how home listeners tune to different stations, programmers can study tuning to their station in great detail using a computer program such as Arbitron’s Maximi$er. Researchers can use this program to tabulate persons in the sample who heard any given station—your station—by all the categories of demographics. You can see which other stations your listeners tune in, and when they are likely to do so. It is possible to see whether your cume audience consists of listeners who used it as their primary station, or heard it only occasionally. Further, the program gives demographic information about each reported listener and the zip code in which they live. The zip code data are often used by stations to find “holes” in their signal area or places to do more advertising—billboards, for example. You can customize a presentation to an advertiser showing precisely what type of listener you can offer, based on demographics and other lifestyle and consumption variables.

This kind of information is valuable to television organizations as well as to radio stations. In fact, the average television viewer undoubtedly watches more channels than the average listener uses stations. Programmers can use promos for the station most effectively by knowing when different kinds of viewers are tuned in. Sometimes that will mean paying attention to the geodemographics of the audience, just like an advertiser. But it is especially important to know when people who watch a competitor’s program are watching your station. That can be the perfect opportunity to entice those viewers with promotional messages.

How Do Structural Factors Like Scheduling Affect Program Audience Formation?

One of the recurring questions a television programmer must grapple with is how to schedule a particular program. Often, scheduling factors are considered at the time a program is acquired. In fact, some programs sold in barter syndication require stations to broadcast them at a particular time. As we saw in chapter 7, that is because the syndicators also sell time to advertisers, and only certain scheduling arrangements will allow them to deliver the desired audience. In any event, how and when a program is scheduled will have a considerable impact on who sees it.

Programmers rely on a number of different “theories”—really just strategies—for guidance on how to schedule their shows. Unfortunately for the student, there are nearly as many of these theories as there are programmers. A few of these notions have been, or could be, systematically investigated through analyses of ratings data. Among the more familiar programming strategies are the following.

A lead-in strategy is the most common, and the most thoroughly researched. Basically, this theory of programming stipulates that the program that precedes, or leads into, another show will impact the second show’s audience. If the first program has a high rating, the second show will benefit from that. Conversely, if the first show has low ratings, it will handicap the second. This relationship exists because the same viewers tend to stay tuned, allowing the second show to inherit the audience. In fact, this feature of audience behavior is sometimes called an inheritance effect (see Webster & Phalen, 1997). The ratings differential between The Late Show with David Letterman and The Tonight Show with Jay Leno is attributed, in part, to strength of their lead-in ratings.

Network programmers have to consider not only lead-in strategies within their own schedules, but the strength of their prime-time lead-in to affiliate news programs. In 2009 NBC scheduled Leno at 10 P.M., expecting its unique (and less costly) content to compete more effectively with scripted programs on the other networks. But NBC’s audience ratings declined in the time period, and affiliates complained that the weaker lead-in hurt ratings for local news. Less than 6 months after the change, Leno moved back to The Tonight Show at 11:35 P.M. Early news experienced the same kind of ratings loss when The Oprah Winfrey Show went off-air. ABC affiliates had been used to the strong lead-in for the news; suddenly ratings in the time period dropped precipitously.

Another strategy that depends on inheritance effects is hammocking. As the title suggests, hammocking is a technique for improving the ratings of a relatively weak, or untried, show by “slinging” it between two strong programs. In principle, the second show enjoys the lead-in of the first, with an additional inducement for viewers to stay tuned for the third program. CBS used this strategy by scheduling 2 Broke Girls after How I Met Your Mother and before Two and a Half Men—both highly successful comedies. Likewise, ABC’s Suburgatory benefitted from its placement between hit comedies The Middle and Modern Family.1 Hammocking works especially well when each program runs promotional spots for the upcoming show.

Block programming is yet another technique for inheriting audiences from one program to the next. In block programming, several programs of the same general type are scheduled in sequence. The theory is that if the viewers like one program of a type, they might stay tuned to watch a second, third, or fourth such program. Public broadcasting stations have used this strategy to build weekend audiences by scheduling blocks of “how-to” programs. In many cases, this block earned some of the highest ratings for stations. A variation on block programming is to gradually change program type as the composition of the available audience changes. For example, a station might begin in mid-afternoon when school lets out by targeting young children with cartoons. As more and more adults enter the audience, programming gradually shifts to shows more likely to appeal to adults, thereby making a more suitable lead-in to local news. Basic cable channels, like TVLand, sometimes do “stunts” that resemble block programming. For example, they may schedule marathons in which many, or all, of the episodes of a program are aired over a period of days. Mini-marathons may show 6 or more hours from one program.

All of the strategies described here attempt to exploit or fine-tune audience flow across programs. Incidentally, many of these programming principles were recognized soon after the first ratings were compiled in the early 1930s. Then, as now, analyses of ratings data allowed the programmer to investigate the success or failure of the strategies. Basically, this means tracking audience members over time—the cumulative measurements we discussed in chapter 6. Conceptually, the analytical techniques needed to do that are just the same as those used to study the loyalty, or “disloyalty” of a station’s audience.

Figure 8.1 shows the results of a flow study analyzing the adult 18–34 audience for ABC’s Wednesday night programming. The first row identifies the sources of audience flow; arrows connect each box to the corresponding program in the second row. The third row identifies where audiences went after they viewed each program on ABC. The horizontal arrows between programs tell us how much of the first program’s audience stayed with ABC to watch the next show—expressed as a percentage and as rating points.

FIGURE 8.1. ABC Wednesday Audience Flow, Adults 18–34

Source: Turner Research from The Nielsen Company data. A18–34 Live Data 2/15/2012 & 2/22/2012.

The chart tells us, for example, that 71 percent of The Middle’s audience stayed tuned for Suburgatory, contributing 1.0 rating to Suburgatory’s 1.5 rating. This raises other questions. First, where did 29 percent (0.4 rating) of The Middle’s viewers go? The bottom row tells us that the “missing” 0.4 rating from The Middle was distributed among several different programs, and 0.07 turned off the set. The second question we want to answer is, from where did Suburgatory gain the 0.5 rating that was not delivered by its lead-in? For this information we look at the box in the top row that points toward Suburgatory. The 0.5 rating came from several different programs, but the biggest single source of viewers was people tuning in at 8:30 P.M. (0.19 of the program’s rating is from tune in).

Should We Continue to Produce This Program?

When Will a Program’s Costs Exceed Its Benefits?

Ultimately, programming decisions must be based on the financial resources of the medium. Although some new stations or networks can be expected to operate at a loss during the start-up phases of operation, in the long run the cost of programming must not exceed the revenues that it generates. This hard economic reality enters into a programmer’s thinking when new programming is being acquired or when existing programming must be canceled. Because ratings have a significant impact on determining the revenues a program can earn, they are important tools in working through the costs and benefits of a programming decision.

When stations assess the feasibility of a new television program, whether syndicated or locally produced, it is typical to start with the ratings for the program currently in that time period. Based on current ratings and station rates, analysts calculate the revenue that can be generated in that time period. This can become very complex because many factors, including uncertainty about the size and composition of a new program’s audience, affect the revenues a program generates.

If a programmer is not evaluating programs to acquire, he or she may have to worry about when a program should be canceled. Much of the press about television ratings has been over network decisions to cancel specific programs that are well liked by small, often vocal, segments of the audience. Ordinarily, a program will be canceled when its revenue-generating potential is exceeded by costs of acquisition or production.

The cost of 1 hour of prime time programming has risen steadily. Today, 1 hour of prime time drama can easily cost over $1 million to produce. Terra Nova, a dinosaur-filled series produced by Steven Spielberg for the 2011–2012 season, cost an estimated $4 million per episode (Dumenco, 2011). Despite having reasonably good ratings (3.6 among adults 18–49), its cost caused Fox to cancel it after just one season. As a rule though, ratings go a long way toward determining which series are renewed. And with increased audience fragmentation, the “cancellation threshold” has been falling. In the mid-1970s, networks routinely canceled programs when their ratings fell into the high teens. By the mid-1990s, programs with ratings in the low teens could remain in the schedule (see Atkin & Litman, 1986; Hwang, 1998). Nowadays, not even the top 10 programs consistently deliver ratings in the double digits; the average prime time household rating for ABC, CBS, and NBC ranges between 6.0 and 9.0. In fact, many programs on broadcast networks now survive with ratings in the 2.0 to 4.0 range.

Dwindling ratings, which are the result of increased competition for the viewer’s attention, can be tolerated for a number of reasons. First, the total size of the television audience has increased, so one ratings point means more viewers. Second, CPMs have increased. Third, the FCC now allows networks to own the programs they broadcast, which enables them to make money in off-network syndication. And fourth, ratings do not tell the cost/benefit story unless they are evaluated relative to production costs, as the Terra Nova example illustrates.

The job of programming is probably more challenging today than at any time in the past. There is certainly more competition among electronic media than there has ever been, making the task of building and maintaining an audience more difficult. Television programmers, in particular, must contend with more stations, more networks, and newer technologies. As they face these challenges, programmers will continue to rely on analysis of ratings data to understand the audience and its use of media.

Carroll, R. L., & Davis, D. M. (1993). Electronic media programming: Strategies and decision making. New York: McGraw Hill.

Eastman, S. T., & Ferguson, D. A. (2013). Media programming: Strategies and practices (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Ettema, J. S., & Whitney, C. D. (Eds.). (1982). Individuals in mass media organizations: Creativity and constraint. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Fletcher, J. E. (Ed.) (1981). Handbook of radio and TV broadcasting: Research procedures in audience, program and revenues. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Fletcher, J. E. (1987). Music and program research. Washington, DC: National Association of Broadcasters.

Gitlin, T. (1983). Inside prime time. New York: Pantheon Books.

Lotz, A. (Ed.) (2009). Beyond prime time: Television programming in the post-network era. New York: Routledge.

MacFarland, D. T. (1997). Future radio programming strategies: Cultivating listenership in the digital age (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Newcomb, H., & Alley, R. S. (1983). The producer’s medium. New York: Oxford University Press.