www.flickr.com/photos/lizjones

IMAGINE THAT YOU are a freelance graphic designer. You get a call from Sam Mullins, who owns the Mullins car dealership empire in your city. They have several large and successful car dealerships. He wants you to take over his account and provide all the graphic design work for all the car dealerships. It’s a lucrative opportunity.

But it also turns out that Sam Mullins has been the enemy of your best friend for years. There is a feud between them that goes back to high school. Do you move forward with the meeting with Mullins and risk your friendship with your best friend? Or do you cancel the meeting, thereby keeping your friendship but giving up lots of potential and profitable work?

Let’s walk through your reaction to this dilemma:

![]() You would probably imagine a series of possible scenarios and the outcomes of each. Your new brain would be actively working.

You would probably imagine a series of possible scenarios and the outcomes of each. Your new brain would be actively working.

![]() If you continued to follow a rational new brain process, then next you would analyze each scenario and its consequence. You would conduct the equivalent of a cost-benefit analysis for each scenario in your new brain. You would analyze how much business might be gained from the new client. You would analyze the likelihood of really ruining your friendship and analyze the benefits that your relationship gives you. You would consider the consequences of losing that relationship.

If you continued to follow a rational new brain process, then next you would analyze each scenario and its consequence. You would conduct the equivalent of a cost-benefit analysis for each scenario in your new brain. You would analyze how much business might be gained from the new client. You would analyze the likelihood of really ruining your friendship and analyze the benefits that your relationship gives you. You would consider the consequences of losing that relationship.

![]() You would continue to create and imagine these scenarios, and you could continue to analyze the cost-benefits. This process would take a long time. You might not even reach a decision. It might be too complicated to remember all the scenarios, all their outcomes, and all the cost-benefit analyses. You might lose track and get distracted.

You would continue to create and imagine these scenarios, and you could continue to analyze the cost-benefits. This process would take a long time. You might not even reach a decision. It might be too complicated to remember all the scenarios, all their outcomes, and all the cost-benefit analyses. You might lose track and get distracted.

In reality, this is not how you make such decisions. Here is what really happens:

![]() It is true that you would start with imagining a series of possible scenarios. This happens visually. Little “movies” play in your new brain as you imagine what might happen.

It is true that you would start with imagining a series of possible scenarios. This happens visually. Little “movies” play in your new brain as you imagine what might happen.

![]() As each movie plays in your new brain, your mid brain and your old brain react. You will have “gut” feelings. Some of the movies will make you feel good and others will make you feel bad. This is your mid brain that is active.

As each movie plays in your new brain, your mid brain and your old brain react. You will have “gut” feelings. Some of the movies will make you feel good and others will make you feel bad. This is your mid brain that is active.

![]() The movies that make you feel bad will be picked up by the old brain. The old brain will sense threat, or danger to your well being, and will send out alarm signals telling your mid brain and new brain that a particular movie is dangerous and should be avoided. Of course, the mid brain and old brain activity is not under conscious control or even conscious monitoring. But the old brain signal of danger, and the mid brain reaction of not liking the movie, will eventually be picked up by the new brain, and the new brain will “decide” to reject that particular action and to look for another alternative.

The movies that make you feel bad will be picked up by the old brain. The old brain will sense threat, or danger to your well being, and will send out alarm signals telling your mid brain and new brain that a particular movie is dangerous and should be avoided. Of course, the mid brain and old brain activity is not under conscious control or even conscious monitoring. But the old brain signal of danger, and the mid brain reaction of not liking the movie, will eventually be picked up by the new brain, and the new brain will “decide” to reject that particular action and to look for another alternative.

This automatic signaling from the old brain and mid brain protects you from losing something. It’s also an efficiency measure, since you will end up with a smaller set of alternatives to decide among.

Our old brain and mid brain react quickly to choices and reduce our alternatives based on minimizing loss.

Is It a Snake?

THE OLD BRAIN, mid brain, and new brain all work together. Here is an example that is often used.

Have you ever been walking in the woods and you are suddenly startled by something on the path ahead of you? Before you can think what is happening you have jumped back, your heart is racing, your adrenaline is flowing. Is it a snake? Did you see a snake? Oh, you realize, it is just a stick that kind of looks like a snake. Your heart rate returns to normal and you continue on your way.

What just happened?

Remember when we talked about the amygdala? The amygdala (there are two of them, one in the right half of your brain and one in the left half) is where emotions are processed. There are two pathways in and out of the amygdala:

![]() One comes from the new brain.

One comes from the new brain.

![]() The other is a direct path from the senses.

The other is a direct path from the senses.

LeDoux’s (1996) and Phelps (2005) both studied the research on the amygdala. From their work, the theory has emerged that the two pathways in and out of the amygdala work together. Information from the senses will reach the amygdala very quickly, but the amygdala isn’t capable of processing sensory detail. The amygdala will not “see” the details of what your eyes saw. So the information will only be a vague image or idea. Your eyes are seeing something, and that sensory information is coming through that “low road” pathway to your amygdala—the path that goes directly from the senses to the mid brain. The amygdala can’t process visual information the way the new brain can, so it doesn’t see the stick clearly. It only registers something that “kind of maybe” looks like a snake, but that is enough to have the mid brain talk to the old brain and set the alarm bells ringing. You react, jump back, and have an entire chemical and hormonal reaction that prepares you to fight the snake or flee from it. While all that is going on, the visual part of the new brain has now analyzed the “snake” and realized that it is a stick. That took longer than the automatic old brain and mid brain reactions, so your body had its automatic reaction before the new brain kicked in with the analysis.

There are two pathways for sensory information into our brains: A fast one through the amygdala and a slower more thorough one through the new brain.

IF I ASK you where you were and what you were doing on July 16, 2002, chances are you won’t be able to remember. But if I ask you where you were and what you were doing on September 11, 2001, you will be able to tell me in minute detail where you were and what you were doing. If you are an American and over 40 years old, I can ask you the same question about where you were and what you were doing when the space shuttle Challenger exploded and everyone on board was killed, including a teacher. You can probably remember details from that date. And if you are over 55 years old, you can probably tell me where you were and what you were doing when President John F. Kennedy was shot.

How is it possible that you can remember these events from long ago, and yet you’ve forgotten most details from all the other days?

It’s because of the amygdala. The amygdala codes any events that produce emotional reactions. The result is that these emotional events are remembered better than events that were not connected with strong emotions.

Phelps (2005) describes experiments in which participants were shown a blue square while simultaneously receiving a mild shock. When we are aroused or upset, our skin emits a tiny amount of sweat. It’s not enough for anyone to notice, but a sensor on the skin will pick it up as an increase in the skin conductance response (SCR). When the participants in Phelps’ experiment received the mild shock, their SCR increased. Before too long, experimenters needed only to show the blue square to elicit an increase in SCR. When researchers scanned the brains of the participants, they also saw their amygdala light up when they were shown blue squares—supporting the notion that simply imagining a fearful event is enough to activate the amygdala.

The hippocampus is involved in memory and is located directly next to the amygdala in the mid brain. The amygdala identifies that something should be feared, and the hippocampus connects that feeling to conscious cognitive experience and memory in the new brain. When we are afraid, we are aroused, and when we are aroused, we remember better. (Actually, it’s really the opposite. When we are aroused, we forget less quickly, so that’s kind of the same thing as remembering better.)

When we are emotionally aroused, whether negatively or positively, we forget the event less quickly, which means we encode it into our long-term memory more effectively.

Your Unconscious Is Smarter Than You Think

THESE EMOTIONAL RESPONSES can occur without us being aware of them. The amygdala responds to the emotional significance of what is going on around us long before it responds to cognitive awareness. In a research study, Whalen (1998) showed faces with emotions, such as fear, to participants so quickly that they weren’t even aware that they had seen anything. But the fMRI brain scan revealed that their amygdala had lit up. The amygdala is deciding what is important and what we should pay attention to—and remember, we’re not aware of it. The amygdala is especially tuned into situations in which we should be afraid of losing. We are programmed to pay attention to, and to avoid, loss.

The best research study on the unconscious fear of losing was conducted by Bechara and others (1997). Participants played a gambling game with decks of cards. Each person received $2,000 of money that he or she knew wasn’t real (but it was designed to look real in an effort to fool their unconscious). They were told that the goal was to lose as little of the $2,000 as possible, and to try to make as much over the $2,000 as possible. There were four decks of cards on the table. The participants turned over a card from any of the four decks, one card at a time. They continued turning over a card from the deck of their choice until the experimenter told them to stop. They didn’t know when the game would end. The participants were told that every time they turned over a card, they earned money. They were also told that sometimes when they turned over a card, they earned money but also lost money (by paying it to the experimenter).

At the beginning of the game, participants didn’t know how much money they would gain or lose for any particular card. They also didn’t know if the four decks were the same or if they were different. They discovered how much they earned or lost only after a card was turned over. They weren’t given any information about how they were doing (in other words, there was no tally they could look at). They also weren’t allowed to keep a tally themselves on paper or take notes of any kind.

The participants didn’t know any of the rules of the gambling game:

• If they turned over any card in decks A or B, they earned $100. If they turned over any card in decks C and D, they earned only $50.

• Some cards in decks A and B also required participants to pay the experimenter a lot of money, sometimes as much as $1,250. Some cards in decks C and D also required participants to pay the experimenter, but the amount they had to pay was only an average of $100.

• Over the course of the game, decks A and B produced net losses if participants continued using them. Continued use of decks C and D rewarded participants with net gains.

• The rules of the game never changed. Although participants didn’t know this, the game ended after 100 cards had been “played” (turned over).

So what happened? Did they figure out the rules and use some decks more than others?

Most participants started by trying all four decks. At first, they gravitated toward decks A and B because those decks paid out $100 per turn. But after about 30 turns, most turned to decks C and D. They then continued turning cards in decks C and D until the game ended.

During the study, the experimenter stopped the game several times to ask participants about the decks. The participants were connected to a skin conductance sensor to measure their SCRs. Their SCR readings were elevated when they played decks A and B (the “dangerous” decks) long before participants consciously realized that A and B were dangerous. When the participants played decks A and B, their SCRs increased even before they touched the cards in the decks. Their SCRs increased when they thought about using decks A and B.

Eventually, participants said they had a “hunch” that decks C and D were better, but the SCR shows that the old brain figured this out long before the new brain “got” it. By the end of the game, most participants had more than a hunch and could articulate the difference in the two decks, but a full 30 percent of the participants couldn’t explain why they preferred decks C and D. They said they just thought those decks were better.

Again, our mid brains and old brains are watching out for us and are particularly sensitive to the prospect of losing. They will signal an alarm long before the conscious mind is aware that anything is wrong.

One of the most interesting results of this study was the spike in skin conductance (SCR) before participants were aware of differences in the decks. Their bodies and their unconscious minds knew what was happening before their conscious minds knew.

Our old and mid brains know what is going on before our new brain does.

What Are We Afraid Of?

SO WHAT IS it we are afraid of losing, anyway? It’s all sorts of things. We’re most afraid of losing what we already have. In the example at the beginning of the chapter, where you weighed the prospect of losing a friendship with the potential of gaining a new client, it is most likely that you will give up the potential work to hold on to the friendship because you already have the friendship. (Remember the adage, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”)

Losing What You Almost Have

BARRY SCHWARTZ (2004) researched people buying cars. Participants test-drove cars with all the options.

• In one condition, they were shown the price of the car with all the options. If they said the price was too expensive, they then were asked to take away the options in an effort to reduce the price.

• In another condition, they were shown the base price of the car (without options) along with a description and price of each option. They were asked to select which options they wanted to add, increasing the price with each option.

We will spend more money in the first condition. The theory is that we have experienced the car in its entirety and will be reluctant to lose what we, in some sense, feel we already have.

Subtract, Don’t Add

THE WEB SITE that follows uses the same principle discussed in the previous section. The model of computer you are configuring in this example already has the better processor. It is “included in price.” If you want to spend less money, then you choose a lesser processor and subtract money. This uses the Fear of Losing principle—we’re reluctant to take away or subtract items. This means we’ll spend more money than if we had started with a lower-end (and less expensive) processor and were asked to spend more money to get a better model.

If the choices subtract, rather than add, then they are using the Fear of Losing principle.

In order to entice us to spend more money, it’s even better if the Web site shows us the entire package (preferably in a compelling photo or, even better, a video.) With photos and video, we can see and almost feel all the options, hear the rich sound of the speakers, or be wowed by the large screen. Then if we feel we can’t afford the entire package, we have to face the idea of taking away options—an idea we don’t necessarily like. If we experience the entire package, we will be even more reluctant to take something away.

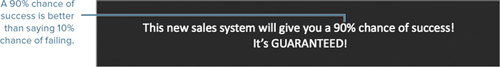

DAMASIO (1994) POINTED out that we have such an automatic fear of losing, that even the way things are phrased can be important. He cited research in the medical field showing that when patients are told “if you undergo this medical treatment, you have a 90 percent chance of living,” patients choose the treatment. If, however, patients are told “if you undergo this medical treatment, you have a 10 percent chance of dying,” patients are much less likely to choose the treatment.

So even the way you word something can trigger the fear of losing.

THERE ARE MANY ways that fear of losing can be triggered while online. Certainly the fear of losing privacy can stop us from taking action at a Web site. We might be afraid that by filling out a form that includes our personal information, someone will use that information to start marketing new products to us.

A friend told me about a fun IQ test that someone sent her. She answered the first five questions, and then the site asked two personal questions, one of which was her birthday. She suspected the site was asking her for personal information, so she used a random birthday.

As covered in Chapter 3, research showed that we were more willing to fill out a form after we had received useful information. That is one way that Web sites can alleviate the fear of losing.

Fear of Losing Security

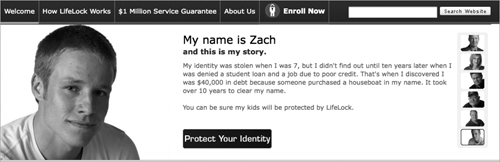

ALTHOUGH MOST YOUNG people are not afraid of purchasing items on the Internet, many older individuals (who have not grown up online and aren’t as familiar with the technology) report that they are afraid to purchase items online because they fear identity theft. In this case, their fear of losing might prevent them from taking an action to purchase.

In fact, some Web sites can make a compelling call to action by combining fear of losing with other techniques, such as telling stories.

Fear of losing security is very motivating.