Chapter 9

Right to Control Access: The Trump Card

When the history of copyright law is written, the digital debate of 1998 will be primarily about access or, more specifically, about the right to control access to digital works. From time immemorial, authors sold copies of their works to the public and that was how they made money. The individual who purchased the work owned the copy but not the copyright. The purchaser could place the book in a personal library, read it at leisure, loan the copy to a friend, or give it away. For the person who possessed the hard copy, it was always there to review and research if the spirit moved him or her.

But in a digital world, works are less frequently sold and more often licensed. Combined with the fact that, in an online environment, works are placed on remote servers and users pay a fee to access them, licensing and access are the core concepts of copyright exploitation in the digital millennium.

When a user employs a computer and the Internet to access a work on a remote site, several things of copyright importance happen. The computer receives an electronic transmission via a modem or similar device and makes a copy of the work in the random access memory (RAM) of the computer. That process enables a user to view the work. With the aid of the computer, a user can transfer the document from RAM to a file on a hard drive. Once on a hard drive, a user can send a digital copy of the file via e-mail to friends and family or simply keep a copy for future reference. That digital copy can be viewed as text, graphics, sound, photographs, or motion pictures. Also, that copy can be a perfect clone of the original.

However, as many know, ingenious computer programmers can create instructions and barriers to the performance of many tasks. Some instructions can require information like a passcode, a word, or phrase so exact that failure to provide it will leave the user unable to open a file. In other instances, a computer user may be able to copy a work onto a hard drive, but embedded in the work may be a set of instructions that make the file unusable. Alternatively, the file may be coded to be accessible for a period of time, for example, a week, and then, it can be ordered to vanish. Now, some wizards (a.k.a. hackers) can decode or countermand these instructions. When these talented hackers overcome barriers, copyright owners feel vulnerable, and their control over their works is subject to the whims of the programming experts, who can take works and treat them without regard to any limitations, even reasonable ones. These concerns were at the center of the DMCA debate over technological protection measures and restrictions on access to works.

As a precursor to the digital debate of 1998, copyright owners (primarily representatives of major movie studios, record labels, software and book publishers) asked U.S. representatives negotiating updates of international copyright laws to add certain treaty obligations covering these digital issues. They did so, and when the delegates returned to the United States, Congress was urged to change US. law to satisfy the mandate of the Berne Convention. (See Chapter 19 for more details on the Berne Convention.) At the top of their agenda was a statutory change that would declare anyone unlawfully accessing a digital copyrighted work protected by a technological protection measure (TPM) to be civilly and criminally liable for infringement.

Their argument was that bypassing these devices was akin to breaking into a locked house. If one was not authorized to access a work, then one should not be allowed to circumvent measures that a copyright owner lawfully placed on the work. The ban on circumvention that owners sought had two parts to it. First, the owners wanted to prevent the manufacture and sale of devices that could technologically open the digital locks. Second, the owners wanted to make an individual's action of circumvention unlawful as well.

Opponents of a ban on circumvention suggested the changes would decimate the balance that existed in copyright for decades. If one cannot access a work, then there would be no opportunity to engage in independent criticism, scholarship, and teaching. There can be no fair use of works that cannot be lawfully accessed, it was argued.

Equipment manufacturers sought a standard for the creation and dissemination of equipment consistent with the standard adopted by the US. Supreme Court in a seminal case in the 1980s debate over the videocassette recorder (VCR). In an important copyright fair use case named for the Sony Betamax machine, the Supreme Court held that the VCR was a lawful device (Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.). Even though the Betamax machine facilitated widespread, unauthorized copying of movies and other audiovisual works, it had a legitimate fair use purpose. The VCR permitted people in their homes to record programs off the air, in case the telecast was at an inconvenient time, and shift the viewing to a better time. This “time-shifting purpose” was a fair use, in the Supreme Court's view. Because the VCR had an important noninfringing purpose, its manufacture and sale did not violate copyright law.

By analogy, computer device manufacturers sought a similar standard with regard to digital content. If a computer or software program could bypass a technological measure designed to prevent unauthorized access (for example, a passcode or encryption formula) to permit a noninfringing use (e.g., a fair use for educational purposes), then the access limitations would be rendered harmless as far as that equipment or device was concerned.

In the end, Congress sided with the copyright owners. It concluded that the threat of digital theft facing copyright owners was far greater than any they faced in more than a generation. Prohibition on the manufacture, importation, sale, or trafficking in any technology, product, service, device, or component was decreed. The ban affects equipment, devices, processes, and services whose “primary purpose” is to be used in defeating technology that limits access to copyrighted works. The new law prohibits any equipment or services that (1) are primarily designed or produced for the purpose of circumventing a TPM, (2) have limited commercially significant purposes or uses other than circumvention, or (3) are marketed for use in circumventing TPMs.

At the same time, Congress grappled with what to do about individuals who bypassed TPMs. Again, the breaking and entering analogy to the locked digital warehouse was raised. Even though one can engage in fair use under copyright law without having purchased a work, the affirmative act of using someone else's passcode or disabling encryption code to access a work that one has no license to see was deemed unacceptable behavior. Therefore, the DMCA includes a key provision that prohibits unauthorized circumvention: “No person shall circumvent a technological measure that effectively controls access to a work protected under this title.” That is strong medicine in a digital world.

However, in two modest bows to those concerned about the broad sweep of the anticircumvention rules, Congress crafted two compromises.

Copyright Off ice Periodic Rulemaking Proceeding

In the first instance, on a periodic basis, the Librarian of Congress (principally through the Copyright Office) is instructed to review how the law is being or should be implemented and determine whether persons are being prevented from exercising fair use and other privileges set forth in the limitations to copyright rights. If the results are too restrictive of fair use and other copyright limitations, the Copyright Office is allowed to fashion limited relief It can carve out those particular classes of works for which the limitations are being unduly restricted and exempt those works from the rule entirely. As part of the phase-in approach to the DMCA prohibition, Congress delayed implementation of the prohibition on persons accessing protected works without authority for 2 years (until October 28, 2000) while the Copyright Office conducted its first study of the new rules.

The DMCA instructed the Librarian of Congress, in doing this study, to consider several factors including (1) the availability for use of copyrighted works; (2) the availability for use of works for nonprofit archival, preservation, and educational purposes; (3) the impact of the prohibition on circumvention on criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research; and (4) the effect of circumvention of TPMs on the market for or value of copyrighted works.

After the initial 2-year study by the Copyright Office, completed in October 2000, the Librarian of Congress determined that only two specific classes of works should be exempt from anticircumvention restrictions:

- Compilations consisting of lists of websites blocked by filtering software applications.

- Literary works, including computer programs and databases, protected by access control mechanisms that fail to permit access because of malfunction, damage, or obsolescence.

Since the first study was initiated before the prohibition on user circumvention took effect, little empirical evidence of harm to users could be found, which was the hallmark test for the Copyright Office. Once TPMs become standard elements of more digital content, the true impact of the DMCA reform will be felt and the question whether users have reasonable access to the digital works or viable alternative works will be answered. The next study must be concluded by October 28, 2003.

Exceptions to the Prohibitions

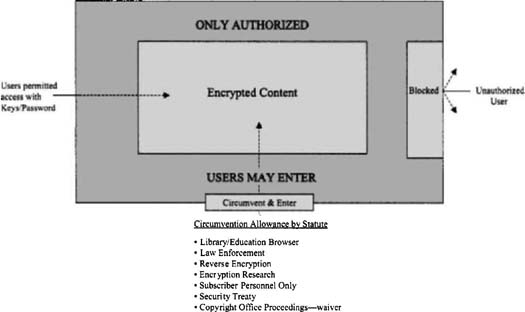

In the second instance, Congress adopted a group of explicit exceptions (Figure 9-1) to the anticircumvention prohibition:

- Nonprofit libraries, archives, and educational institutions: browsing right. Qualifying public institutions are permitted to circumvent TPMs to gain access to a copyrighted work solely to make a good faith determination whether to acquire a copy of the work. This accessed copy cannot be retained longer than necessary to make the determination and may not be used for any other purpose, and the work must not be otherwise reasonably available in any form. Violations of the limitation subject the nonprofit organization to civil damages, and repetitive violations can result in loss of the exemption. The exemption is not a justification to traffic in prohibited equipment.

- Law enforcement, intelligence, and other government activities. Federal and state government law enforcement authorities are not restricted by this statute.

- Reverse engineering. A lawful user of a computer program may circumvent TPMs to ensure that the program can work with other programs (interoperability), provided there is no readily available commercial alternative for that purpose. The research may be shared with others, as long as it does not constitute a copyright infringement of the original or related work.

- Encryption research. Circumvention is permitted in the context of “good faith encryption research” with respect to copies lawfully acquired. Persons availing themselves of this exemption must have tried to get permission from the original owner and cannot engage in practices deemed a violation of computer fraud laws.

- Personally identifying information. Circumvention is permitted to detect and disable technology that collects and then distributes information about an online subscriber that was not authorized by the subscriber.

- Security testing. Circumvention is permitted for good faith efforts at accessing a computer system or network (with permission of the owner) to investigate and correct a security flaw.

- Analog devices. The law requires compliance by analog recording device manufacturers with anticopy technologies that do not affect the playability of the machines or restrict lawful activities.

- Other rights not affected. The statute provides that nothing in the new access rules affects the rights, remedies, limitations, or defenses available in cases of copyright infringement or any right of free speech or press for persons using consumer electronic, communication, or consumer products. While this sounds like a broad limitation, the clear intent of this provision is to recognize the prior obligation of the user to obtain authorized access to work. Once lawful access is obtained, the other limitations and defenses of copyright law (such as fair use) and the Constitution come into play. However, if a person who lacks lawful access cannot assume that fair use or free speech will apply if he or she chooses to circumvent a TPM. Moreover, any subscriber whose paid online subscription has expired should not presume a right to circumvent a TPM to make fair use of content in the period of the original subscription. Indeed, a strict reading of the law says he or she cannot.

Sidebar to the DMCA Debate: Judiciary and Commerce committees Clash over Jurisdiction

An interesting sidebar in the DMCA debate that told much about the way laws are made was a jurisdictional tussle over congressional authority to regulate matters affecting the Internet and its transmissions. While copyright jurisdiction lay with the Judiciary Committees in the House and Senate, the Commerce Committee in the House wanted to participate in deciding how Internet communications were regulated. The dispute helps explain why the final structure of the DMCA incorporated participation not only of the Copyright Office (which reports directly to the Judiciary Committees), but also the National Telecommunications Information Administration (NTIA), which is within the Department of Commerce, an agency overseen by the Commerce Committees.

Copyright Management Information

In an attempt to ensure the integrity of any information included with digital works that the owner intends to use for management purposes, the DMCA prohibits the removal or alteration of copyright management information (CMI) or the dissemination of false CMI. CMI is defined in the law to include

- The title and other information identifying the work.

- The name and other information about the author.

- The name and other information about the copyright owner.

- The name and other information about performers, writers, and directors of qualifying works.

- Terms and conditions for use of the work.

- Identifying numbers or symbols.

- Other information that the Register of Copyrights may appropriately prescribe.

Law enforcement, intelligence, and other information security activities, as well as certain public performances by radio and television stations, are exempted from portions of these prohibitions.

Penalty Provisions

The DMCA added new, substantial penalties for anyone caught violating the prohibitions on unauthorized access, manufacturing, or trafficking in banned equipment and devices. Persons who violate the access prohibitions are subject to awards of actual damages and profits or statutory damages of no less than $200 nor more than $2,500 per act of circumvention or per device sold or service offered. Violators of the CMI rules can recover statutory amounts ranging from $2,500 to $25,000 per violation. A nonprofit library, archive, or educational institution can escape damages if it can establish that it was not aware and had no reason to believe that its acts constituted a violation. These institutions are also exempted from any criminal sanctions, which include fines up to $500,000 and imprisonment for up to 5 years (doubled in the case of repeat offenses). As with other copyright laws, injunctions against certain practices can issue and the prevailing party can be awarded attorney's fees.

Early Decisions Uphold the Anticircumvention Rules

A few early cases tested the constitutionality of the DMCA access rules, and so far, the validity of the statute has been upheld. The most notable decision involved DeCSS, a computer program designed to bypass TPMs and allow DVDs to play on Linux-based operating equipment. We have more to say about this decision, but for the moment it is important to note that the important Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a decision that the DeCSS software violated the DMCA and was not an instrument of fair use or free speech.

So the copyright law moves into the 21st century with a new twist. The grant of rights covering uses of works has been extended to the right to control access in digital formats. The power to restrict who can see a work has enormous educational and social implications. Those effects will be felt for decades to come.

Moving On

We presented the broad framework of copyright—the outer layers of law—and discussed its practical applications. Now, it is time to approach another wing of IP rules important for content-trademark law. Once we have a grounding in the philosophy of this sister body of rules, we can appreciate the shading and nuances necessary for better understanding of media content rights.

But, before we move on, let's summarize the core premises of copyright law.

Core of Copyright

- Authors are entitled to exclusive rights in their works for limited times.

- The copyright rights are broadly defined to cover copying in any format, creating derivatives, and publicly performing, displaying, or distributing a work.

- The rights are subject to crucial exemptions, including fair use, compulsory licensing, and educational uses.

- The law provides powerful remedies to enforce the rights.

- There are no longer any prerequisites to claiming copyright; the original work need only be fixed in a tangible medium.

- The term of copyright is for an author's life plus 70 years (95 years if an entity).

Now, on to trademarks.