TOGAF®

General Presentation

Abstract

This chapter presents the foundations, positioning, and principles of TOGAF and introduces some dedicated vocabulary, as well as the structure and key concepts of the framework. It also discusses the architecture development method as an enterprise architecture transformation approach integrating different facets (business, system, technical) into its process and the place of the organization.

This chapter presents the foundations, positioning, and principles of TOGAF and introduces some dedicated vocabulary, as well as the structure and key concepts of the framework. It also discusses the architecture development method (ADM) as an enterprise architecture transformation approach integrating different facets (business, system, technical) into its process and the place of the organization.

1.1 What is TOGAF?

1.1.1 Positioning and history

TOGAF1 has long been recognized as a major reference in the field of enterprise architecture. It is successful because it meets a real need: the need for a common framework that will facilitate the capitalization and mutualization of architectural practices throughout a community. More specifically, TOGAF is positioned as a generic method, which groups together a set of techniques focusing on the transformation of enterprise architecture.

Developed by The Open Group (TOG) international consortium, the current version of TOGAF (version 9.1, December 2011) is the result of work carried out over several years by dozens of companies. Released in 1995, the first version of TOGAF was based on TAFIM,2 itself developed by the DOD.3 Initially built as a technical framework, TOGAF then evolved, resulting in version 8 (“Enterprise Edition”) in 2003, whose content focused more on the enterprise and the business. Version 9 continued and built on this orientation. In 2008 a certification program was put in place, and today more than 20,000 people around the world are TOGAF-certified.

The sheer size of the TOGAF reference document (nearly 750 pages) should not overshadow the orientation of the project, which focuses on the enterprise architecture transformation approach. This approach, described by the ADM, constitutes the heart of the reference document.

1.1.2 “A” for Enterprise Architecture

The “A” of TOGAF implies “Enterprise Architecture” in all its forms and is not limited to information systems (ISs). Admittedly, the goal remains the implementation of operational software systems, but to achieve this goal, a wider view is required, covering strategic, business, and organizational aspects. Moreover, the alignment of “business” and “technology” is a major concern for business managers and chief information officers (CIOs), who are constantly looking for IS agility. Architecture therefore covers requirements and strategies as well as business processes and technical applications and infrastructures and strives for optimal articulation between these different facets. It should be pointed out here that the term enterprise is not limited to its legal sense, but rather designates any organization linked by a common set of goals.5

In this context, TOGAF provides a pragmatic view of enterprise architecture, while highlighting the central role of organization. Any architectural transformation requires close collaboration between the different people involved in the enterprise architecture. Governance, stakeholder management, and an architecture-dedicated team implementation are among the many subjects dealt with by TOGAF.

This collaboration is based on an organized process. It is the role of the ADM to provide a structure for the progress of architectural transformation projects. Communication plays a vital role here. At each stage of transformation work, a common understanding of the goals and the target must constantly be sought. The media used (documents, models, etc.) must be clearly defined and adapted to the different participants.

Beyond the implementation of architecture projects, capitalization and reuse are constantly present goals. Consequently, the task of setting up an architecture repository is central to TOGAF. This repository can include all sorts of elements, such as examples, norms, models, rules, or guidelines. Fed by the different work carried out, the repository guarantees centralization and homogeneous distribution throughout the enterprise.

1.1.3 “F” for framework

A framework groups together a collection of means and procedures dedicated to a particular field of activity. When used as a reference and a tool, a framework is most often presented as being complete and consistent for the field in question. TOGAF does not go against this definition. It provides a language, an approach, and a set of recommendations covering all facets of enterprise architecture, from organization and strategy, to business and technology, to planning and change management.

At first glance, this diversity can be disconcerting, due to its generic and pragmatic nature. However, this approach reveals the maturity of the project, which does not try to impose a universal, finished solution, preferring instead to provide a toolbox that can be used by all participants in enterprise architecture, from senior management, CIOs, and business managers to IS architects and project managers.

Naturally, the genericity of the TOGAF framework means that each company adapts it to its own context, for example, by adapting the framework, identifying the specific stakeholders, and so on. TOGAF allows for a phase dedicated to setting up and adapting the framework. We look at this subject in Section 1.4.

Does TOGAF have the answer to everything? It goes without saying that a novice will not be transformed into an enterprise architecture expert just by reading the reference document. As with everything, experience remains invaluable, but in view of the complexity of the subject, an organized framework and recognized method constitute an essential asset.

1.1.4 The TOGAF document

In concrete terms, TOGAF is presented in the form of a single reference document7 and a dedicated web site.8

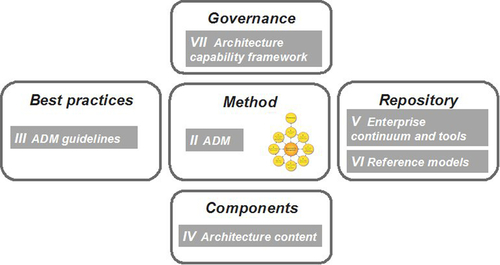

This document is broken down into seven parts:

II. ADM (Architecture Development Method)

III. ADM Guidelines

IV. Architecture Content

V. Enterprise Continuum and Tools

VI. Reference Models

VII. Architecture Capability Framework

Figure 1.1 presents an overview of the breakdown of the different parts of TOGAF: Method, Best practices, Components, Repository, and Governance.

The ADM (part II, “Architecture Development Method”) is the main entry point to the TOGAF reference document, with its crop circle diagram (or TOGAF wheel), which describes the different phases of the method.

Part III discusses guidelines and best practices linked to the ADM, from security and gap analysis to stakeholder management. It should be noted that in general TOGAF does not provide “standard solutions” but rather a series of practices “that work,” accompanied by more or less detailed examples.

Part IV (architecture content) is dedicated to the tangible elements used in development work: deliverables, catalogs, matrices, diagrams, or the “building blocks” that constitute the architecture.

Parts V and VI focus on the enterprise architecture repository, and its partitioning, typology, and tools.

Part VII (“Architecture Capability Framework”) deals with architecture governance, including repository management.

We look at the different parts of the TOGAF document in the following chapters:

• Chapter 2: The ADM and Guides for the ADM (parts II and III)

• Chapter 3: Architecture Content (part IV)

• Chapter 4: Repository and Governance (parts V, VI, and VII)

1.2 TOGAF: Key points

1.2.1 ADM and the TOGAF crop circle diagram

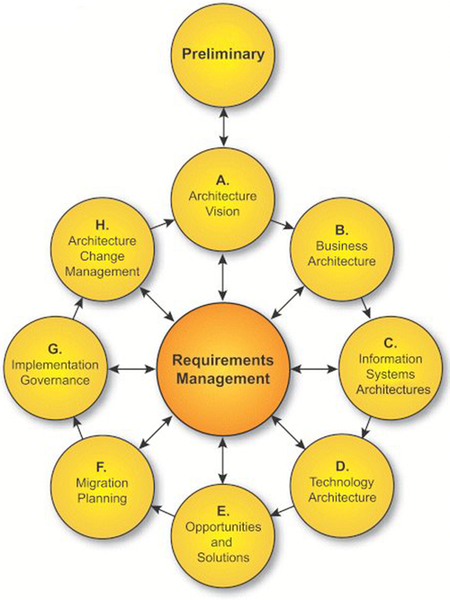

The ADM crop circle diagram presents the structure of the method with its phases and transitions (Figure 1.2), and is the first striking image encountered when broaching TOGAF.

In classic fashion, the phases define the high-level work stages, which consume and provide products (deliverables). Each of the eight phases contributes to achieving determined strategic objectives, from the overall vision of the architecture (phase A) to the maintenance of the deployed architecture (phase H).

This sequence, called the ADM cycle, takes place in the context of an architecture project managed by the enterprise’s executive management. The work carried out is supervised by the architecture board, in partnership with all the business and IS stakeholders.

As you can see, the proposed path is a cycle, which finishes by looping back on itself. Admittedly, this is merely a schematic representation that only partially represents reality. However, it does successfully express the continuous nature of enterprise architecture work, which responds to the constant demands of businesses.

The central position occupied by requirements management in the diagram is testament to the pivotal role it plays within the ADM cycle. Strictly speaking, requirements management is more a permanent activity than a phase. However, the term “phase” is used to designate it in order to harmonize vocabulary. The same is true for the preliminary phase, which groups cross-organizational activities such as the definition of context, methods and tools for enterprise architecture, and the start of an ADM cycle.

Fundamentally, the aim of an ADM cycle is to successfully complete a transformation project, whose aim is to enable the enterprise to respond to a set of business goals.

1.2.2 Architecture transformation

From baseline architecture to target architecture

As we have just seen, enterprise architecture transformation is at the heart of the subject matter dealt with by TOGAF, which discusses the following questions in detail:

• How to organize oneself?

• How to communicate?

• What are the main risks and how can they be reduced?

In this way, TOGAF distinguishes itself from other Zachman9-type frameworks, which primarily propose a typical architecture structure, and concentrate far less on the actual transformation approach. However, TOGAF provides its own content framework, with its specific terminology and structure (Figure 1.3).

But let’s get back to the heart of the matter: Which approach should be adopted to make our enterprise architecture evolve? This can be summed up in four points:

• Knowing where we are coming from

• Determining where we want to go

• Choosing the best path to get there

• Successfully completing the transformation

Knowledge of the baseline architecture is not always clearly established. Consequently, a more or less detailed “reappraisal” of what already exists is often necessary. All the more so when we consider that the transformation roadmap depends on the gap analysis between these two states, and on the impact that this transformation has within the enterprise.

Determining the destination, that is to say the target architecture, depends above all on business goals, but also on a series of technical, organizational, and budgetary factors.

Finally, the means used to conduct the transformation must be chosen. What is the timeframe? How can we guarantee that certain critical parts will continue to function? How can we best prepare participants confronted with changes in their activities?

Transforming architecture

Any person who has been confronted with the exercise will say the same thing: making enterprise architecture evolve is a delicate and complex activity. Successfully completing transformation means fully understanding all the constraints that apply to this type of operation.

First off, any evolution of enterprise architecture requires that a large number of highly dependent elements be coordinated. Consequently, the involvement of the different stakeholders is a determining factor in the success of the operation, especially when we consider that this evolution often has significant consequences on the enterprise itself, its activities, and its employees.

Furthermore, the conditions that start an architecture project are diverse, ranging from the introduction of new services or products or the renovation of a part of the system, to internal restructuring or company mergers or buyouts and acquisitions, and so on. This means that the reference framework must have a certain degree of flexibility, since too much rigidity would run the risk of “jamming” the machine.

The scope covered by the transformation also has an influence on the variety of situations encountered. In most cases, we are not building a complete system “from scratch.” On the contrary, developments generally concern specific parts of the system, linked to business goals.

Enterprises behave like living organisms, constantly reacting to external requests. Like a shop that advertises “business as usual during renovation,” the enterprise never suspends its activities, since continuity of service must be guaranteed.

To sum up, the road to follow is not “preordained.” However, the framework can help accelerate and guide change initiative, although the combination of parameters that must be taken into account means that it will always need to be adapted to a particular context.

Transition architectures and increments (states)

How do you move from existing (baseline) architecture to target architecture? The answer to this question, provided in the form of a path (or migration architecture), is a key element of TOGAF, founded on the following principles:

• If it is to succeed, this path must take into account all the facets of the enterprise, and the effects resulting from all changes.

• The path includes intermediate states, described by the transition architecture.

• These intermediate states must bring real, measurable added value.

• Gap analysis between the target architecture and the baseline architecture is a determining element in the choice of path.

Operationally speaking, this path results in a series of implementation projects of various different types: software development or evolution, data migration, training, and business reorganization. The successful coordination of these different projects goes a long way to determining the success or failure of the operation (Figure 1.4).

The number of states varies according to the domain, scope, time horizon, and level of details as well as the difficulties encountered. A direct transition (with no intermediate states) to the target architecture is possible where the gap between the baseline architecture and the target architecture is limited. Progress through states reduces resistance to change, and reduces risk by making adjustments easier.

The description of this migration path is one of the major TOGAF10 deliverables, notably for developing the operational project schedule.

Gap analysis

In order to choose the appropriate path between two states, the gap between these two states must be analyzed. The same is true when transitioning from a baseline architecture to a target architecture.

The principles of gap analysis are relatively simple. The comparison of baseline architecture and target architecture results in answers to the following questions:

• Which elements are new (organizations, applications, infrastructures)?

• Which elements have been deleted?

• Which elements have been modified?

• Which elements remain unchanged?

However, these results must be considered alongside the business goals of the transformation, in order to check their pertinence. Is the deletion of such and such an element appropriate? Have we forgotten to add such and such an element?

Chapter 27 of TOGAF (Gap Analysis) proposes the use of a baseline/target matrix, which highlights differences and makes them easier to analyze.

One advantage of this tool is that it proposes a systematic approach, which helps avoid “flaws.” During the different phases of the ADM, the aim is to identify elements that have potentially been overlooked, but that play an important role in measuring the gap between baseline and target architectures, and that will be significant to the change operations that are to be carried out. Beyond aspects linked to IT systems, this gap measures the distance that must be covered if the enterprise is to be capable of meeting new business goals: for example, employee skills, modifications to organizational structures, or the availability of technical means.

Impact evaluation

An enterprise is often a complex organization with multiple branches. Consequently, the modification of one part of its architecture may potentially affect other components situated outside the scope of the implemented changes.

First, the impact can be technical: any modification of a software component can potentially have repercussions on all the components that use it.

Second, the changes made can also indirectly affect certain business aspects. For example, increasing the number of products available will probably have an impact on how other products are presented.

Finally, the restructuring of an enterprise’s organization, even partial, can have repercussions on the way the enterprise functions, through the relationships that exist between different departments and their members.

We will see that during architecture development phases, gap analysis and impact assessment go hand in hand, each influencing the other in terms of architecture choices and transition management. Even though this development initially focuses on its scope, it must take into account the enterprise in its entirety.

The concept of capability

Capability designates the ability of an organization to provide a given product or service. Capability manifests itself through a series of factors that contribute to the realization of these products or services at the required level of quality. These factors can vary widely in type: for example, personnel training, availability of an expert in a field, surface area of premises, power of IT servers, and so on.

The notion of capability is also widely used in other frameworks. ITIL defines it as being “The ability of an organization, person, process, application, IT service or other configuration item to carry out an activity.”11 It is also naturally found in the acronym CMMI (capability maturity model).

The fact that this term appears nearly 500 times in the TOGAF document is testament to just how essential it is to consider a business function as a whole, far beyond a strictly “IT system” view. The enterprise must be able to satisfy its clients, and in order to do this, it must be fully operational. Even the most perfect application can only function in an environment that is able to use it. A badly informed user, a badly adapted procedure, or unmotivated management will inevitably prevent the realization of the defined goal.

More generally, the goal of an ADM cycle is to improve or put in place new business capabilities. This goal is present during each phase, so as to coordinate the different dimensions of the architecture (business, system, and technology) in order to converge on the final solution. This goal also applies to each step of the path, as we saw earlier.

In TOGAF, two chapters are specifically dedicated to this:

• Chapter 32, “Capability-Based Planning,” a technique for planning the transition from baseline architecture to target architecture based on capabilities.

• Part VII of the TOGAF document, “Architecture Capability Framework,” deals with the organization and governance of enterprise architecture. We discuss this point further in Chapter 4.2. Here, the term “capability” designates all the organization elements that have to be implemented in order to guarantee efficient management of enterprise architecture.

1.2.3 Architecture in TOGAF

Architecture and description of architecture

We have already spoken at length about architecture and transformation, but it is useful at this point to refresh our memories regarding the term “architecture” and its content. In its introduction,12 TOGAF gives two definitions of the term “architecture”:

1. “A formal description of a system, or a detailed plan of the system at component level, to guide its implementation.”

2. “The structure of components, their inter-relationships, and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution over time.”

The first definition considers the term “architecture” as a synonym of “system description.” For the second, “architecture” designates the structure and principles of the system, independent of its description.

This double definition may seem surprising, but it does reflect a very real situation. Software systems are, by nature, opaque, so much so that their structure is only visible through representations. Factories, ships, or engines all have a physical structure, which is more or less visible. However, it is impossible to “lift the hood” of an IT system, whose architecture only exists through its representation. This is also the case for business elements such as processes, organization, or strategy, which can only be communicated through descriptions or models. The proliferation of schemas, diagrams, and tables within enterprises is testament to this reality.

In this context, communication on architecture plays a determining role. Just like the blueprints of a building, communication is a vital tool for those working on the different tasks involved: development, evaluation, exchange, and construction. In this book, we have chosen to focus particularly on this point, through the use of concrete examples (Chapters 6–11).

Domains and phases

What are some of the main subject areas in enterprise architecture? TOGAF proposes a high-level breakdown into four large domains:

• Business architecture, which covers strategy, goals, business processes, functions, and organization.

• Data architecture, dedicated to the organization and management of information.

• Application architecture, which presents applications, software components, and their interactions.

• Technology architecture, which describes the techniques and components deployed, as well as networks and the physical infrastructure upon which the applications and data sources run.

This breakdown is unsurprising and fairly similar to other proposals on the same subject, although each has its own particularities and vocabulary.13 Chapter 3 takes a more detailed look at the contents and structure of TOGAF architecture.

The first part of the ADM approach is structured using the same typology, with one main difference: only three phases are dedicated to the elaboration of the architecture: business (phase B), IS (phase C), and technology (phase D). The IS architecture phase has two subphases (data and application), which correspond to the two aforementioned domains. From here on, we either use the term “IS architecture” or else directly refer to “data architecture” and “application architecture.” Figure 1.5 summarizes the two structures (by domain and by phase) used in TOGAF.

We see in Chapter 3.2.4 that this equivalence between architecture domains and ADM phases, while pertinent at first glance, is not strictly valid in detail.

Architecture repository

Naturally, enterprises need to conserve, diffuse, and reuse the EA information that constitutes one of their key assets. This is the role of the architecture repository, which includes descriptions from each of the four domains, as well as a whole host of knowledge, guiding principles, and techniques linked to enterprise architecture. Far from being a static source of information, the repository is constantly evolving throughout architecture transformations, thereby participating in know-how capitalization. It also provides an overview of the architecture, which facilitates decision making at a strategic level.

Architecture and solution

For TOGAF readers, one item of vocabulary still has to be explained. TOGAF often refers to solution architecture. Here, the term “architecture” designates a description, and more precisely a logical view, as opposed to the “solution,” which represents a technical reality. This distinction can be clearly seen in the terms “Architecture Building Block” and “Solution Building Block” (respectively ABB and SBB). The logical specification of an element is an ABB, while its physical equivalent is a SBB. These two types of element are present in the architecture repository, which enables either the documentation or the physical component to be reused, according to the context.

1.2.4 Goals, constraints, and requirements

To successfully carry out a transformation operation, we must be perfectly clear about the results we hope to obtain. This statement may seem trivial, but it is worth bearing in mind.

In this domain, TOGAF distinguishes a series of elements that participate in a more structured formalization:

• Strategic objectives, or goals, which describe general orientations.

• Operational objectives, or objectives, which formalize these goals in terms of measurable results at a given date.

• Drivers, which often motivate decisions regarding architectural change, such as changes in conjecture or the need to adapt to technical evolutions. These are the “why,” which justify and orient goals.

• Requirements, which specify exactly what will be concretely implemented to reach these goals.

• Constraints, which are external elements that influence the system, sometimes restraining its capacities.

How are these elements integrated into an architectural project? Let’s immediately remove any ambiguity: the role of an enterprise architect is not to define objectives (strategic or operational) for an organization. However, he/she will formalize them within a structured context, and will use this formalization to better link decisions and architectural elements. Despite its imperfection, this kind of “traceability” between system components and desired results is extremely useful, since it helps reduce the risk of “technological” dispersion by constantly focusing on the business vision of the architecture and facilitates high-level impact analysis.

1.2.5 Stakeholders and the human factor

We know that the organizational aspect is one of the most delicate points in this type of operation. Like any enterprise process, architecture transformation involves a combination of activities involving different participants, each one of them a “stakeholder” in the operation he or she undertakes.

TOGAF deals with this question through the following themes:

• Transformation Readiness Assessment

• Efficiency of communication through the concept of viewpoints

Managing stakeholders

First, it is essential to clearly define each stakeholder as early as possible during the ADM cycle. This identification mainly uses a pragmatic approach in order to avoid simply reusing existing organizational structures, which only partially represent the reality of the activities and responsibilities that will be put in motion. Leaving a key participant by the wayside would significantly affect the quality of the results. Consequently, in order to determine with whom and in what form work will be carried out, a series of key questions must be answered on the subject:

• Who gains and who loses from this change?

• Who controls the transformation process?

• Who designs new systems?

• Who will make the decisions?

• Who procures IT systems and who decides what to buy?

• Who controls resources?

• Who has or controls the necessary specialist skills?

• Who influences the project?

From these questions, TOGAF recommends that the position of each stakeholder be clarified, notably his or her degree of involvement. Figure 1.6 presents these different degrees.

Each stakeholder will be positioned using these degrees of involvement, which determine the relationships to develop and the level of involvement in architecture project steering committees. Naturally, key players play a determining role and must be on the front line in all areas of decision making.

This qualification is cross-referenced with the role played in the context of the current project:

• The executive management, who defines strategic goals

• The client, who is responsible for the allocated budget, with regard to the expected goals

• The user, who directly interacts with the system in the course of his or her activities

• The provider, who delivers the component elements of the architecture, notably its software components

• The sponsor, who drives and guides the work

• The enterprise architect, who turns business goals into reality within the structure of the system

Transformation Readiness Assessment

Is the organization ready for the envisaged change? This question may seem incongruous, but how many projects have finished unsuccessfully because this dimension was not taken into account? In just a few years, “change management” has become a discipline in its own right, producing a large number of articles and seminars.

Chapter 30 of TOGAF14 is entirely dedicated to this question, which is widely discussed in the description of the ADM phases. The identification of change resistance risks and the definition of actions to take to limit these risks are essential tasks that must be carried out before embarking upon a transformation project. This is particularly important for an operation covering a broad scope and resulting in significant restructuring.

While it is not possible to provide turnkey solutions on such a subject, it is possible to use certain techniques that will help reduce this type of risk:

• A clear presentation of the impacts of changes made, notably on an organizational level

• A concrete view of the expected business benefits, in the form of “business cases”

• An objective assessment of the enterprise’s IT, business, and financial aptitudes, with no overestimation of its real capacities

• An executive management team recognized as being able to defend the project in the long term

• High-quality communication, which aims to promote a common understanding of the stakes and the solutions to implement

Views and viewpoints

If a message is to be successfully understood, the most important aspect to consider is that its content and form must be tailored to the intended recipient.

For this, TOGAF uses the concept of viewpoints. A viewpoint designates the most appropriate perspective for a given participant, and is materialized by a certain number of views of the architecture, in the form of diagrams, documents, or other elements. For example, executive management will be more interested in a high-level description, while communication with operational staff will require much more detailed representations.

This is a critical point, one that will condition the quality of communication and that will be encountered during each phase of the ADM cycle. Consequently, it is imperative that views and viewpoints be defined for each stakeholder before beginning work on the four architecture domains (business, data, application, and technology). We discuss this question in detail in Chapters 7–10, with examples taken from TOGAF views.

1.2.6 Architecture strategy, governance, and principles

A strategic view of enterprise architecture

We have just seen that implementing transformation constitutes the main theme of TOGAF. We have also seen that architecture transformation is driven according to business goals defined for a specific scope.

However, a wider, more long-term perspective is also necessary. It is clearly up to the enterprise’s executive management to define general goals and develop the strategy. These translate into decisions concerning architecture, notably in terms of evolutions to the IS.

In a framework such as TOGAF, this aspect is found in the form of links between business strategy elements and system components. The formalization of “drivers,” “strategic goals,” or “business requirements” is included in the business architecture part of TOGAF. This formalization of the “why” contributes to a common understanding of business fundamentals, and clarifies the role of each component in a wider perspective.

Moreover, architecture choices will affect the system for years to come. The system must meet today’s requirements, but must also be able to adapt to tomorrow’s needs. Ensuring overall consistency on the functional and technical levels is therefore vitally important for those in charge of enterprise architecture.

Governance

In a complex organization, this strategic view cannot be taken for granted. Consequently, to slow down the centrifugal forces and retain a certain level of overall consistency, it is essential that an appropriate organization be established. This organization, which is centralized by nature, uses a cross-organizational mode of governance that handles architecture in terms of the enterprise, its strategic choices, its principles, and its action plan.

This organization, called the “architecture board,” is responsible for the following goals: to guarantee that common rules are respected, and to ensure that implementation projects are supported. In its capacity as a steering and control committee, the architecture board also takes care of managing the architecture repository. We go into more detail on this point in Chapter 4.

Architecture principles

Architecture principles provide invaluable help in this strategic view of the architecture. They establish a set of rules and recommendations, which encourage the harmonization of choices and practices.

TOGAF recommends that these architecture principles be established as early as possible, as a unifying element for future projects. Architecture principles are a kind of table of statutes, which must respect the following properties:

• Stability: Principles are stable by nature. They are only rarely modified compared with the frequency of developments.

• General scope: A principle applies to the entire enterprise, and does not depend on the transformation carried out.

• Comprehensibility: A principle is interpreted clearly by all stakeholders.

• Coherence: With regard to the set of principles. Two principles cannot be contradictory.

Every time a transformation project is begun, each participant must be able to consider these principles as a guide, and use them as a basis for his or her choices.

TOGAF provides an example of a relatively detailed catalog of architecture principles,15 which includes around 20 principles organized into four families similar to the four architecture domains: business, data, application, and technology.

Rules on relatively diverse aspects are found in this catalog, such as:

• The systematic involvement of users in architectural choices

• The harmonization of application design

• Continuity of service

• The respect of intellectual property protection rules

• The sharing of information

• Data quality levels

• The harmonization of vocabulary

• Security

• Independence with regard to technical platforms

• Ease of use

• The respect of deadlines

• The respect of standards

The reader can refer to the TOGAF document for a more detailed description. Each principle is described in a standard way: the name of the principle, its statement and rationale, and its implications.

This catalog is a relatively broad basis upon which each enterprise can establish its own set of architecture principles. It goes without saying that the wide range of enterprise histories, businesses, and priorities makes individually adapted formulation essential.

It should also be noted that there is no point in having too big a catalog. It is always preferable to work on a limited number (a few dozen) of widely accepted principles, rather than a multitude of badly assimilated rules.

In practice, the catalog of architecture principles is often built based on existing elements, from several sources or spread across different organizations. Where this is the case, the main task is to compile and consolidate information based on the aforementioned characteristics.

1.3 Summary

By way of a partial conclusion, let’s recall the foundations of the TOGAF project:

• Business goals. Architecture is above all based on an enterprise’s business goals. Constantly present at every stage of work, they act as the main driving force for change.

• The “human factor.” Enterprise architecture is implemented by staff members, teams, and organizations. The quality of the results obtained depends greatly on the commitment of all participants.

• Communication. The main aim of enterprise architecture is the facilitation of communication between participants. This means that architecture formalization and communication must be mastered, at all decision-making levels.

• Capitalization and reuse. Beyond the context of methodological frameworks (of which TOGAF is an example), accumulated experience is an irreplaceable asset. Sharing through a common repository constitutes one of the key elements in this regard.

• The use of standards. As a long-term activity, enterprise architecture is built on a solid and durable base. In this way, TOGAF takes responsibility for a series of acquisitions recognized by the community.

• Governance. Solid and efficient governance, which drives transformation work and maintains overall architectural consistency.

Figure 1.7 presents a summarized view of the approach and its main components. As a “machine” used to transform enterprise architecture, the ADM cycle is based on business goals, the initial state, and the principles that govern the entire architecture. This operation draws on elements from the repository, and is driven by dedicated governance. Each stakeholder is linked to a viewpoint that describes the architecture through a series of adapted views. Requirements guide the choice of solutions for the target architecture. The implementation plan defines the transition path, organization, implementation, and monitoring of the new architecture.

1.4 Using TOGAF

1.4.1 Adapting the framework

As we have already seen, TOGAF is not intended to be used as is, as one would use a recipe in cookery, where each step is faithfully followed to produce a final result.16 On the contrary, TOGAF is presented as the foundation upon which an organization builds its own architecture framework. Adapting TOGAF is therefore one of the first activities to carry out, one that will guide all future operations. This adaptation is an integral part of TOGAF, which provides the necessary practices and principles.

Adaptation takes place on two levels:

• The definition of the general framework, used in each cycle of the ADM

• The adjustment for each cycle, according to its particularities

This adaptation is carried out during the preliminary phase. It is essential to remember that enterprise architecture transformation is not a unique project, but rather a permanent activity consisting of specific architecture projects for each ADM cycle, providing feedback that enables the overall framework to be adjusted.

Adaptation can take place on several levels:

• Vocabulary, the basic architecture entities

• Deliverable templates

• Architecture principles

• Architecture elements: catalogs, matrices, diagrams

• The phases of the ADM and their possible iterations

• Architecture governance

• The first view of the architecture repository

This includes adapting to what you are trying to accomplish with the EA:

• Manage your portfolio of applications

• Address new business influencers

• Address new competition, the introduction of a new disruptive technology, and so on.

These examples illustrate how flexibly the entire ADM cycle can be used, and show how fully it plays its role of generic blueprint. However, it is important to explain and justify the iterations chosen through a detailed plan before embarking upon the whole cycle in order to avoid improvisation during the work itself.

Furthermore, this flexibility in no way weakens the value of the TOGAF framework, which provides both a “compass” and content. These will both be vital during the implementation of architecture evolution, which remains a complex activity that is difficult to control.

1.4.2 TOGAF: One framework among many?

TOGAF is not defined in an isolated manner. On the contrary, the joint use of other frameworks is recommended, since each brings added value to its sphere of operation. “In all cases, it is expected that the architect will adapt and build on the TOGAF framework in order to define a tailored method that is integrated into the processes and organization structures of the enterprise. This architecture tailoring may include adopting elements from other architecture frameworks, or integrating TOGAF methods with other standard frameworks, such as ITIL, CMMI, COBIT, PRINCE2, PMBOK, and MSP.”17

TOGAF and DODAF

DODAF (Department of Defense Architecture Framework)18 provides an architecture management and representation framework. The concept of the viewpoint, also found in TOGAF, plays a central role, linked to governance and stakeholder management.

DODAF viewpoints are structured as follows:

• Capability Viewpoint (CV)

• Data and Information Viewpoint (DIV)

• Operational Viewpoint (OV)

• Project Viewpoint (PV)

• Services Viewpoint (SvcV)

• Standards Viewpoint (StdV)

• Systems Viewpoint (SV)

As in TOGAF, each viewpoint is broken down into a collection of views, each designed to represent a part of the architecture. For example, the operational viewpoint includes the following views:

• OV-1 High Level Operational Concept Graphic

• OV-2 Operational Node Connectivity Description

• OV-3 Operational Information Exchange Matrix

• OV-4 Organizational Relationships Chart

• OV-5 Operational Activity Model

• OV-6a Operational Rules Model

• OV-6b Operational State Transition Description

• OV-6c Operational Event-Trace Description

• OV-7 Logical Data Model

A fairly similar approach can be found in the MODAF19 framework, notably with regard to the use of viewpoints and views.

Despite the fact that these frameworks (DODAF and MODAF) are established in a governmental context, and more specifically in the field of defense, they can be used in other contexts. Where necessary, the definition of viewpoints and views can be used to adapt them to the TOGAF framework.

TOGAF and ITIL

ITIL is a framework dedicated to managing ISs. ITIL has been popular since the mid-2000s, notably after the release of version 3 in 2007.20

The main ITIL concept, the service center, clarifies the position of the IS within the enterprise as a provider at the service of its clients, be they internal or external. It establishes a set of recommendations and best practices that aim to control system quality, in terms of reliability, response to needs, and risk reduction.

ITIL deals with all aspects linked to the management of the IT system infrastructure through the description of its processes: service deployment, operation, support, security, and lifecycle.

• Problem Management

• Change Management

• Release Management

• Configuration Management

Highly quality oriented, ITIL greatly inspired the ISO 20000 norm, as well as the enterprise certification program. For readers wishing to learn more, there are a number of works on the subject.21

What is the relationship between ITIL and TOGAF? Since version V3, ITIL has been structured into five “volumes,” focused on the notion of service:

• Service design

• Service transition

• Service operation

• Continual service improvement

This structure makes certain overlaps with TOGAF22 appear: service strategy with the preliminary phase and phase A; service design with phases C and D; service transition with phases E and F; service operation and improvement with phases G and H.

At first glance, this correspondence can be interpreted as a similarity between the two frameworks. In this case, should we choose between the two approaches and forbid their simultaneous use?

Beyond these formal similarities, the fundamental difference between the two frameworks is first and foremost a question of perspective. ITIL has been developed as a tool dedicated to IT services used to manage IT systems. TOGAF is clearly oriented toward a business view of architecture and the transformation method.

It is clear what the subjects dealt with during phases G and H of TOGAF, which concern the use and maintenance of IT system components, are also widely present in the ITIL community. However, the development of architecture and its impact on the business and the organization, subjects at the very heart of the TOGAF project, are less prevalent in ITIL “culture.”

It should be noted that neither ITIL nor TOGAF is presented as “turnkey” solutions, but rather as reference frameworks. Consequently, the right attitude for enterprises must probably include a healthy dose of pragmatism, taking the best from both approaches.

TOGAF and CMMI

The CMMI23 is a repository of best practices organized into levels of maturity. It is both a certification framework and a set of processes destined to improve the quality of development projects.

Dissemination of the maturity-level structure is real, and CMMI certification is a guarantee of quality often requested of enterprises. Moreover, this method of evaluating an organization or a system has been used in several different contexts. TOGAF dedicates an entire chapter to this (Chapter 51), and proposes an enterprise architecture maturity evaluation model, which uses the CMMI’s five maturity levels. This model is a result of the “Enterprise Architecture Capability Maturity Model” from the DoC (US Department of Commerce), and is presented below.

1.5 Fundamental concepts

The following fundamental concepts were introduced in this chapter:

• Enterprise architecture framework: Coherent set of methods, practices, models, and guides dedicated to enterprise architecture.

• Architecture transformation: Set of actions that consist of making architecture evolve from an initial state to a final state.

• Impact assessment: Assessment of the impact of an architecture transformation project. Impact can be multifaceted (business, organization, IS, etc.).

• Gap analysis: Assessment of the differences between two architectures (baseline and target).

• Capability: The ability of an organization to provide a given product or service.

• Architecture principles: Set of stable rules and recommendations concerning the architecture in its entirety.