1. An Era of Creative Destruction

Executive Summary

This chapter presents a quick history of exchanges, their purpose, and their development. It delves into the process of floor-based trading, the system used for well over a century on exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). Then it explores the technological innovations that led to the development of electronic exchanges and gives an overview of its process and implications for the future.

Introduction

The book has a primary and a secondary purpose. The primary purpose is to tell the fascinating and important story of how and why those institutions we call exchanges have begun to bear no resemblance to their former selves, of how the stock and derivatives exchanges of the world are being rapidly transformed into institutions that are much more accessible and efficient than their predecessors of the recent past.

The secondary purpose is hidden in the primary one: By telling the story of the transformation and how it is affecting virtually every aspect of the way exchanges function and the way people and institutions trade, the reader will also walk away from the book with a thorough understanding of the organization, role, and function of exchanges today.

The basic story of the transformation is a story of Schumpeter's “creative destruction,”1 in which old systems, old ways of doing things, and old ways of life are being destroyed as new, more efficient, more transparent systems are taking their place. Old jobs disappear and new jobs are created. The clerks, runners, and price reporters are no longer needed to manage the flow of customer orders as the orders shift from voice to keyboard and as the bids and offers are automatically matched and captured. The staffs of both exchanges and brokerage firms are shifting from those who took care of order entry, trade matching, and trade and price reporting on a physical trading floor to those who take care of the hardware and software of screen-based systems.

The traders themselves are moving from floor jobs, where a strong voice and athletic endurance were important, to desk jobs surrounded by six screens, a keyboard, and a mouse. At the extreme, some traders have become black-box babysitters, merely watching as a sophisticated set of programming code makes all the trading decisions at the speed of light. It's a wonderful thing for a trader to drop all his or her accumulated wisdom into emotionless lines of “if-then” instructions, but it also raises questions about the end game. Will trading still be fun a decade from now? Will humans still be involved? In the short term, the exchanges are continually struggling to improve system architecture and increase bandwidth to keep up with growing volumes and the higher frequency and more complex trading styles made possible by electronic access.

But to tell this story in a meaningful way, it is important to explain what these exchanges do, how they are organized, how they are populated, how they innovate, and how they compete and cooperate. So this is really a book that explains the modern exchange and all its most important features, and that is the secondary purpose of the book.

Trading: Simple Concept, Complex Process

A simple definition of trading is the exchange of goods or services and money between buyers and sellers. Whether it is the exchange of agricultural goods or credit default swaps, the essential idea of trading has not changed. Buyers and sellers must meet, negotiate a price, and exchange goods for money. 2 Though people have traded with each other for thousands of years, recent innovations in technology have led to radical improvements in every step of this simple process. Where people once met every fall to sell their crops, farmers can now enter into contracts with buyers around the world who promise to purchase those crops sometime in the future. Where people once negotiated loans to local businesses, they can now trade debt in companies and countries around the world in the blink of an eye. In fact, they can trade insurance on that debt to lower the risk of default. Where people once met face to face under a tree, in a coffeehouse, or on a large trading floor to trade equity in companies, they can now instantly trade shares for almost any company on any market in the world from a computer at home. Technology enables buyers and sellers anywhere in the world to quickly negotiate a price and reliably exchange any product in mere seconds. It has transformed trading into a system that is global, faster, and more complex, requiring a web of infrastructure and regulations that brings every country, market, and individual closer together.

Long ago, people met in various ad hoc venues, such as weekly markets, churches, coffee shops, or town halls. Individuals were responsible for finding buyers or sellers themselves and negotiating the terms for each trade. However, these multiple and separate meeting places meant the pool of potential trading partners was often fragmented and, therefore, the items were not necessarily traded at the best price. As the demand for trading increased, these gathering places became overcrowded and made it more difficult to conduct trades smoothly. These factors prompted the adoption of a designated place to conduct trades in a structured way. This evolution resulted in the modern exchange.

The Birth of Exchanges

From their humble beginnings as a place for buyers and sellers to gather to trade goods, exchanges have grown into complex organizations critical to the global economy. The introduction of exchanges marked the beginning of the modern financial market structure. The exchange was a novel idea introduced to address some of the inefficiencies in early trading and to protect brokers and dealers who were professionally engaged in handling these assets. It provided people a designated place to meet and trade a suite of products with each other. There were specific exchanges to trade agricultural products, others for trading metals, and still more were formed to trade stocks. The formation of exchanges all across the globe has a very interesting and colorful history.

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was formed by 24 stockbrokers under a buttonwood tree outside of 68 Wall Street. The Buttonwood Agreement of 1792 between these brokers read, in part:

We the Subscribers, Brokers for the Purchase and Sale of the Public Stock, do hereby solemnly promise and pledge ourselves to each other, that we will not buy or sell from this day for any person whatsoever, any kind of Public Stock, at least than one quarter of one percent Commission on the Specie value and that we will give preference to each other in our Negotiations.3

The early formation of exchanges was often spurred by the growing interest in trading. In 17th-century England, informal stock trading began to finance the Muscovy Company and the East India Company, which were attempting to reach China and India, respectively. The companies began selling shares to merchants, giving them the potential to earn a portion of any profits made from the voyage. These people frequently met in coffeehouses in London's famous Change Alley. As interest in these and many other floatations of shares increased and the number of participants outgrew the Alley, they moved to a bigger place of their own in 1773 and called it the Stock Exchange. Similarly, the oldest stock exchange in Asia, the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), was also formed by a group of people who regularly met under a banyan tree. When the number of buyers and sellers grew and spilled into the streets, they also agreed to form a designated place for trading by creating an exchange.

Although the history of trading began with agricultural products and metals, trading stocks is mechanically simpler than trading goods because it is merely the exchange of documents entitling the bearer to some fractional ownership of a firm. Commodities, on the other hand, involve the exchange of many head of cattle or bushels of wheat of differing grades, weights and locations. The fluctuation in production caused the prices of these goods to be volatile. To protect themselves from the volatility of prices, farmers, merchants, and agricultural companies began writing and trading contracts for grain to arrive in Chicago on some future date. A futures contract is an agreement between two parties to buy or sell a product at a specified date in the future. Without a central counterparty, the onus was on individuals to ensure that the agreement was honored at the specified delivery date. It was not uncommon for the buyer or the seller to back out of the agreement if market conditions changed dramatically before the time of delivery. The commodity exchanges were formed to standardize these contracts, ensure that both parties honored these trades, and establish a structured delivery mechanism for the goods upon settlement.

Chicago, one of the original birthplaces of modern futures trading, was an ideal location for commodities trading due to its close proximity to farmland. Chicago has long boasted two of the world's oldest commodities markets: the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), founded in 1848, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, CME, originally started as the Chicago Butter and Egg Board in 1898. These markets helped bring together buyers and sellers of commodities in one designated area, thus making it easier to find someone to trade with. Similar markets were created throughout the country to support regional agricultural or other physical commodity products. The New York Mercantile Exchange (currently NYMEX) was one of the largest physical commodity markets, trading everything from butter and cheese to dried fruit, canned goods, and poultry. The Minneapolis Grain Exchange was formed to support the grain farms for the region. Similarly, the London Metal Exchange (LME), the largest and oldest market for metals, had its roots in groups of ship charterers, metal traders, and financiers who would get together in various coffeehouses to trade mostly domestic metal. As demand grew and global trade increased, people began trading metals from regions as far away as South America and Asia. The increasing number of traders and the growing list of metal products prompted the group to form the London Metal Exchange to provide a structured trading location and to better manage the flow of metals traded.

These early stock, commodity, and metal exchanges were formed across the globe to trade a variety of products. They were all formed to eliminate the constant struggle to find a buyer or seller, to provide structure and ensure fairness in trading, and to provide better price discovery. After the birth of these early markets, many exchanges were formed for specific regions or for specific products. For example, there were over 40 exchanges in China at one point, over 20 exchanges in India, and over 250 in the United States. These exchanges served as a designated place, called the trading floor, where the buyers and sellers gathered to trade. Floor-based trading, or pit trading, has been the foundation of financial markets for well over a century. The exchanges transformed trading into a world of organized chaos, although outsiders who see a trading floor for the first time find it difficult to see any order in the chaos. Exchanges eliminated the inefficiencies of locating people to trade with and introduced rules and regulations to ensure fair and orderly trading. They also ensured that products were properly transferred between the two parties after a trade.

Though modern exchanges have evolved into complex organizations by adopting new ideas and innovations to improve their overall structure, the physical floor remained the cornerstone of trading. The model worked successfully for centuries, despite the noisy chaos on the floor.

Figure 1.1 shows the major processes that every trade undergoes. Throughout the book we will be discussing these three main processes and the changes happening within each of these processes. However, the basic concept of these three main processes remains the same.

The trading phase involves the activities associated with trading. This process generally includes steps that traders take to analyze the market or their strategies (pre-trade analysis). Pre-trade risk management is more widely associated with the electronic trading model; it allows risk managers to analyze the risk of a trade before it reaches the exchange. Of course, the trade function also includes the activities of buying and selling products. Clearing and settlement, discussed in greater detail later in this chapter, include the final reconciliation of the trades for the day and actual transfer of funds or the instrument that was bought or sold on the exchange. This process continues even as the financial markets shed their century-old floor-trading (open outcry) model and adopt an electronic trading model.

To understand the current transformation, let's first explore how the open outcry model handled these trading functions.

Open Outcry Trading

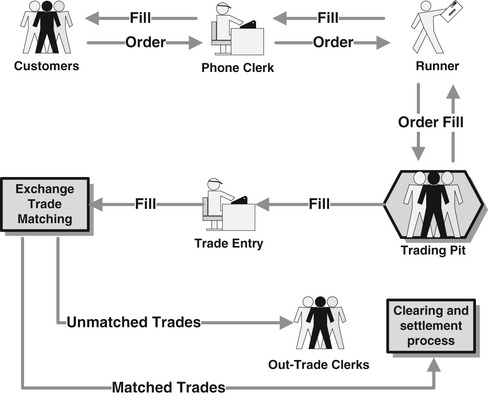

The uninitiated visitor watching a trading floor sees a place full of chaos, emotion, drama, and excitement. But behind this adrenaline-fueled trading model was a structure and process that worked for over a century. It was a tediously manual process requiring hundreds of people on the floor and behind the scenes to ensure that every trade on the floor was accounted for, recorded, executed, cleared, and settled. Trading on the exchange has followed this floor-trading model, also called open outcry, as the primary method of trading. Figure 1.2 details the floor-trading model and the various job functions required to process a trade.

As shown in Figure 1.2, 4 the floor-trading model is extremely people-intensive. A trade touches many hands before it is executed between a buyer and seller. The phone clerks take the incoming orders from external customers and write these orders on slips of paper. The runners deliver these orders to the floor brokers, who gather along with floor traders trading for themselves in a trading pit, an area of a trading floor assigned for a specific product. These floor traders and the floor brokers have traditionally been members of the exchange and the only people authorized to trade on the trading pit. They scream and shout at each other to indicate their orders. Hand signals are commonly used to indicate the price, buy/sell orders, and additional details about the product, such as expiration month, quantity, and type of order. In addition, the runners run from pit to pit to give the floor brokers the orders received by their firm's clients. All these orders are then recorded on a paper or cardboard trade card,5 including the traders’ symbols. 6 These trades eventually reach the market makers/specialists.7 The specialist serves as a human matching engine, posting bid and ask prices, managing limit orders, and executing trades. In the early days, people quickly updated chalkboards with the current bid and ask prices. As the exchanges adopted technology, the prices for products were updated automatically on screens installed throughout the trading floor.

The yelling and screaming continue throughout the trading sessions in the trading pits. As the specialists match the trades, the runners deliver the confirmation back to phone clerks, who notify the customers. The trade clerk enters all the fills for the exchange matching system. By the end of the day, the floor is covered with paper discarded from the day's trading.

As exciting and energetic as floor-trading was, the process for a trade to go from order to settlement was extremely lengthy and cumbersome. The trades often contained an error. The exchange trade-matching process consisted of reconciling all the trades received from the trading pits for the day for the final clearing and settlement process. The process was not pretty. Every day the out-trade clerks would handle numerous out-trades or unmatched trades. The team of out-trade clerks would correct errors made on the floor, such as trades with the wrong price or the wrong quantity (“Fifty” and “Fifteen” often sound the same on a noisy trading floor), and there would be a number of trades that simply could not be corrected. Every morning before entering the trading floor, traders would line up at the out-trade desk to review the list of these error trades. Either these trades would need to be canceled or traders themselves would need to correct the errors. All the matched trades from the end of the day were sent to the clearing and settlement process, the final step in the trade cycle. Generally referred to as back-office processing, the clearing and settlement process is both tedious and complex. These processes further required coordination among the various players in financial markets, and it took days before the executed trades were settled.

The Clearing and Settlement Process

An important step within the trade cycle, the clearing and settlement process ensures that executed trades are matched and processed accurately. Every trade executed on the exchange must flow through the clearing process, where the buy and the sell trades are matched, and at contract maturity the settlement process delivers the funds and the product to the trading parties. 8 A simple process on surface, trade matching and clearing comprises a series of complex steps to ensure that the contractual terms of each trade are fulfilled. Prior to the birth of exchanges, people not only had the burden of finding someone to trade with, they also took on the risk that the trades might not be honored by either the buyer or the seller. For example, let's say that the buyer and seller agreed on a contract for wheat at a specific price. Without the clearing and settlement process, trading parties faced substantial credit and/or default risk. In our example of the wheat trade, the buyer faces issues such as not receiving the wheat or receiving a different quality of wheat than agreed on. The seller faces the risk of not getting the payment for the wheat sold. People traded primarily based on trust and always carried substantial risk of the other party not honoring its side of the contractual obligation of the trade.

The creation of exchanges brought the buyers and sellers together to trade, but the credit and default still remained. To ensure that traders had trust and could trade with anyone on the trading floors, clearing houses were established. The role of these clearing houses is to provide the trading community with trust that the trade obligations will always be fulfilled. A clearing house fulfills this role by acting as a central counterparty (CCP) that serves as the guarantor behind all the trades executed on the exchanges. The CCP takes the burden of the credit and default risk associated with trading. With the CCP as a middleman and as a guarantor of every trade, the trading community can trade on the exchange without the worry of the other party backing out of the trade.

To provide this guarantee, every trade executed on the exchange flows through the clearing and settlement process. Every day millions of trades are executed by trading firms, and every single trade has to go through the complex process at the clearinghouse. The clearing process matches all the trades. All the buy orders for a specific product at a specific price are matched against the matching sell orders.

To minimize the number of trades that flow to the settlement process, clearinghouses perform a process called netting during the trade-matching process. The netting process balances all the buys and the sells executed by the same trading firm for the same security and calculates the net difference, which is the delivery requirement for the trading firm. To guarantee the contractual obligation of these trades, the CCP takes the opposite side for every trade. In the process commonly known as novation, the CCP guarantees the delivery of the financial instrument to the buyer, and the seller is guaranteed the payment for the financial instrument sold, even if one of the parties defaults or becomes insolvent.

Today all the regulated exchanges9 around the world have a clearing and settlement process that provides the trust for the trading community to trade with anyone on the trading floor without the worry of credit or default risk. To ensure a smooth post-trading operation and to be a guarantor for every trade, the clearing and settlement process includes functions such as risk management, margining, and collateral management. Although the basic concept of the clearing and settlement process remains the same across asset classes, there are some key differences in both the clearing process as well as the settlement process between the equities and the derivatives asset class.

Equities

The clearing and settlement process in the equities world is simpler than in the derivatives world. The equities trading process involves the trading of corporate stocks, which requires the transfer of ownership between the buyer and the seller. When a stock is traded on an exchange, this is followed by a transfer of ownership of the stock from the buyer to the seller and a transfer of funds from the seller to the buyer. The clearing process ensures that every executed buy order matches an equivalent executed sell order. The clearinghouse serves as a guarantor of the trade and inherits the risk of the seller not having the stock or the buyer not having proper funding for the stock, though the clearinghouse first looks to the clearing broker to ensure or make good on performance. The settlement process ensures that the ownership and the funds are simultaneously transferred between the buyer and the seller. The settlement process in the securities world is generally referred to as T + n, meaning trade date plus the number of days, n, that it takes for the ownership and funds to transfer. In the United States, securities are settled on a T + 3 basis; most securities exchanges around the world perform settlement on a T + 2 basis, and the clearinghouse carries the risk until the settlement process is complete.

Derivatives

Derivatives such as physical commodities, futures, and options follow a similar process of netting and novation as the equities. In equities trading, the clearing and settlement process is completed in two or three days (depending on the T + n requirement), and the ownership and the funds are transferred in full at the time of settlement. Derivatives, however, are contracts that provide the user the right and/or obligation to purchase these underlying instruments at a later date, which could be months or even years in the future. Due to these long settlement dates, the derivatives positions stay open until the time of the settlement date, which means that the actual delivery does not occur until the future date. This poses a prolonged risk exposure for the clearinghouse, since there is a much longer period during which the buyer or seller could default. To mitigate this risk, the CCP requires the settlement process for the derivatives to be completed on the same day. This means that every day the settlement process takes place based on the daily revaluation of the derivatives contracts. This process is called mark to market. Every contract is revalued based on the day's settlement price, and the buyers and sellers’ accounts are adjusted based on the price changes. This process continues until the expiry date or until the contract is liquidated.

This floor-trading model has been followed globally since the birth of exchanges. There were physical floors around the world to support various asset classes. In addition, the exchanges generally only supported regional or national areas. The exchanges hardly ever had any significant global customer base. For example, at the beginning of the 20th century, there were numerous regional exchanges for the same asset class. For example, the United States and the United Kingdom each had close to 30 different regional stock exchanges. 10 These exchanges seldom competed with each other because there was no way to connect these markets. However, the birth of telecommunications provided an early glimpse at the future of global connectivity. For example, the NYSE earned a larger market share than the Philadelphia Stock Exchange (the first stock exchange in the United States) because it adopted the telegraph, which allowed it to expand by receiving orders from customers not physically located on the trading floor. 11 Later the adoption of the telephone spurred even more competition between exchanges because traders could now get information on other markets via telephone. As telecommunications improved, the floors were filled with telephones to support the increased market participation. More people could now trade by calling in their orders to the trading firms, which would then transmit the orders to the floor brokers. As computer systems were introduced, exchanges adopted them to help specialists store trade data, making it easier to track all the orders received. Although trade volume grew and the number of market participants increased, until the recent technology transformation exchanges functioned in the same manner as before: Traders screaming at each other in open outcry pits.

Technology and Its Impact on Financial Markets

The innovations in computer technology have had a profound and lasting impact on the world. This technology gave rise to the Information Age, which created entire industries that processed data rather than physical goods. From ancient mainframes that filled entire rooms to tiny computers embedded in credit cards, computer technology has rapidly become smaller, cheaper, and more powerful. Computers have been used for decades to store and process massive amounts of data. This eliminated the inefficiency of storing information on paper for people to process manually. Results are obtained quickly and automatically, with fewer errors. Early computers were too large and expensive to be used in many industries, but size and cost were reduced at an astonishing rate. This allowed more industries to employ computers for data processing tasks, culminating in the introduction of the personal computer (PC), which brought this technology to the masses. Today companies and even individuals can easily get access to computers that are as powerful as recent supercomputers. This computing power is now applied to financial markets to react to events in milliseconds and to mine mountains of data for new insights. It is used by exchanges and clearinghouses to process millions of trades per day, as well as by regulators to monitor all those trades. Customers can trade on markets anywhere in the world from their cell phones.

The development of the Internet was required to connect all these computers into a global telecommunications network. Originally developed as a network for military computers, the Internet is like a telephone system for computers, without a central routing authority. Information does not move directly from point A to point B; instead, each message takes its own route through several computers to reach its destination. For this reason, communication on the Internet incurs a small delay, called latency, and can be insecure. To avoid these problems, many financial companies have reused the enabling technologies for the Internet to create a private network directly to the exchange. Large investments in global fiber optics have led to a glut of network capacity around the world. Fortunately, this means there is plenty of bandwidth available between global financial centers.

These technology advancements have driven not only the changes in financial markets but the global economy as well. These innovations have connected the world electronically. They have made information access easy, fast, and cheap. The increasing productivity of companies, economies, and governments has widely been attributed to the Information Age. The Internet and PCs have become integral parts of the global economy and people's personal lives. And just as the Internet and the PC have changed the world, they have had a profound impact on the financial markets. In recent years the financial markets have been full of excitement, energy, and drama, except this time it is not on the trading floor. It is the excitement of watching the technological pioneers and early adopters challenging the century-old floor-trading model. It is the energy of witnessing new jobs and new functions being created in the financial markets. It is watching the drama of pessimists defending the old models and the floor-trading. The Information Age is truly revolutionizing the financial industry.

Trading is an information-intensive activity. In addition to the current trading price for the product, information such as economic news, historical prices, analysis, and trends also plays a critical role in making trading decisions. In the past, the financial markets used technology to improve processes and to add efficiency on the floor. For example, in the old days, chalkboards were updated by exchange employees who sprinted throughout the day to provide the latest bids and offers on products. Technology replaced these human workers with electronic bulletin boards installed throughout the trading floor that were updated via keyboard every time a specialist entered a new bid and offer for a product. In former times, external news on the economy or information about products was generally obtained by traders and brokers on the floor by talking to each other or by calling their firms’ analysts or customer brokers upstairs. Technology brought computer terminals12 onto the trading floors, allowing floor traders and brokers to access external news as well as market data.

Technology adoption, however, primarily benefited the floor and the floor-trading process. For the general public, which was far removed from the floor-trading world, the only way to receive market information was by either calling the broker or reading newspapers and trade journals, but the information was limited and stale. Things today have changed dramatically. Anyone with a PC and Internet connectivity can access the market information for exchanges around the globe in real time. The digital revolution has allowed financial markets to access, store, and process more information than they ever could in the floor-trading days. The wealth of information available today has transformed the way financial markets utilize this information. It has allowed trading firms to redefine their trading strategies and trading styles. It has created a level playing field between the trading community and the general public.

The Decade that Changed the Financial World

Much of the 1990s was a prosperous decade for the world economy. More commonly referred to as the dot-com era, it was a time of unprecedented growth in technology. Today the term dot-com is remembered for the dot-com bust, the eventual collapse of the speculative bubble, but it is the source of many of the positive technological advances that continue to have a profound impact on the world.

The 1980s saw the birth of some well-known companies such as Microsoft, Dell, and Cisco. Companies such as Microsoft and Dell brought personal computers and their operating systems to the general public and the first real glimpse of technology that is part of all of us today. Much of the success of these companies came in the early 1990s, when the Internet made its entrance in the mainstream. The rise of the PC and the Internet created hundreds of companies that went public with simply an idea and a catchy name. Most disappeared when the bubble burst, but they left behind a global electronic network and launched one of the most profound transformations of the global economy.

The dot-coms were businesses created over the Internet, meaning that they conducted most of their business electronically. They challenged the “old economy” to a new one. As the new kids on the block, they did everything differently from the old guard, from business culture to business infrastructure. One of the major business models of many dot-coms was to increase market share first and make money later. Although this proved to be a failed business model, it was partially responsible for the spread of the Information Age. Dot-coms used the Internet to conduct their business. For the first time, people could buy almost anything on the Web. Companies such as Amazon were formed to allow customers to buy everything from books to groceries over the Internet from the comfort of their homes. These new Internet companies relied heavily on technology. Since dot-coms used the Internet to conduct their business, their growth drove the growth in electronic storage, computer processing power, and transferring capacity.

The 1990s brought the general public many new methods of communication. Things such as email, instant messaging, and cell phones, which are embedded in our daily lives today, were in their infancy in early 1990s. The increasing growth in technology saw a dramatic reduction in technology cost. For example, the cost of a three-minute transatlantic phone call dropped from a staggering $245 in the 1930s to $3 by the 1990s and to less than 30 cents by 2007. 13 The cost of storing, transmitting, and processing information dropped 25–30% annually. 14 The dramatic cost reduction, along with the growth of the Internet, brought the people of the world closer together. Communication and information transfers across the globe became easier and cheaper. The growth in technology had a profound impact on almost every industry. Innovation and competition in technology were thriving. Pioneers and new entrants used the new technologies to improve efficiency and processes within their industries. Financial markets, massively dependent on information, began adopting technology to improve their processes. Just as the NYSE took the bold step a century ago to use the telegraph to become the dominant stock exchange, a number of new players began challenging the old model of floor-trading. The rise of technology allowed these new competitors to challenge the status quo and to pave the way for global transformation of the financial markets.

The First Electronic Market

Technology innovation and the growth of computing gave birth to the first all-electronic market: the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (Nasdaq). 15 The market did not follow the traditional floor-trading model, and for the first time there was an equities market that had no designated physical space for trading. It used computers and telecommunications to eventually connect the buyers and sellers. 16 Although a novel concept at the time, Nasdaq remained in the limelight for over a decade, slowly improving itself by adopting technology along the way. Originally the home for small companies such as Microsoft that could not afford the NYSE's listing requirements, Nasdaq slowly grew into the second largest equities market in the United States. Technology advancement in the 1990s saw a significant increase in the number of new startups. Nasdaq became the home for these technology companies that were trying to raise capital to continue to innovate in technology areas. These small companies helped propel the Information Age that is now transforming the global financial markets.

Nasdaq and electronic trading would not have been possible without the innovation in telecommunications and the computer industry. The benefits of technology were seen as early as the birth of the telegraph, when the NYSE became the dominant U.S. exchange. Those early changes are all but forgotten in the past 10 years. Exchanges and financial markets today thrive on liquidity and rely on information to make trading decisions. The technology innovation in recent years brought the exchanges and the financial community just that: surges in volume and wealth of information. The current transformation of financial markets generally and of exchanges specifically can be widely attributed to the rapid innovation in technology.

Electronic Communication Networks and U.S. Equity Markets

The U.S. stock market saw the first hints of electronic trading with the birth of Nasdaq and its electronic price quotations in 1971. But it wasn't until the early 1990s that the U.S. stock exchanges saw a real threat to their livelihood. For the first time in history, the “old boy's club” was challenged, and it was largely due to the birth of electronic communication networks (ECNs) and discount brokers. ECNs and discount brokers used technology to disseminate trade information and to allow trading without the need for physical space. These newcomers provided trade information to the general public that had been available only to the privileged few on the floor and the brokers. Prior to ECNs and discount brokers, the only way the general public could trade was by calling their brokers to place trades. The information one could get was limited and delayed. Discount brokers and ECNs took the information once only available on the floor and provided it electronically to all their customers. They made trading easier and more accessible. Anyone who wanted to trade stock just needed a personal computer and an Internet connection. ECNs and discount brokers provided this information quickly, efficiently, and at much lower cost. People saw their trade transaction cost dropping from over $100 to just under $10. Along with ECNs and discount brokers, 17 Internet companies such as Yahoo! and Microsoft began providing information such as market data, analytics, historical prices, and company data that people needed to make informed trading decisions. And much of this information was provided at very low prices or at no cost at all. Within just a few years of coming into existence, ECNs began handling over 40% of Nasdaq volume. 18

Halfway across the world, technology was having a similar impact on a completely different asset class. Europe was undergoing major transformation of its own at a political and economic level. It was the beginning of the formation of the European Union (EU), a community of major countries in Europe that created a legal and economic system to allow the freedom of movement of people, goods, services, and capital. The collaboration between these countries would require information flow at all fronts. Technology provides the ideal platform to provide a fast, efficient, and smooth information flow between the European countries.

Exchanges and financial markets in various European countries began using technology to develop an electronic platform for trading, which would eliminate the physical boundaries of an exchange and connect the financial systems across countries through cyberspace. Markets such as OM19 began as an electronic trading platform for options in the 1980s. It has since merged with over eight stock exchanges in the Nordic and Baltic countries and is now part of the Nasdaq OMX group. Similarly, technology advancement also led to the very important merger of two electronic exchanges, Deutsche Terminböse (DTB) and the Swiss Options and Futures Exchange (SOFEX), to form Eurex, today one of the largest derivatives exchanges in the world. Around the globe, pioneers began adopting technology to create an electronic trading infrastructure that would give financial markets a facelift.

Technology was being used in financial markets not to simply improve existing processes on the floor but to change the overall architecture of the trading model. Electronic trading leaders such as DTB and Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) began challenging the old model. As we discuss in later chapters, there were plenty of new entrants in electronic trading and, similarly to dot-coms, most of the early ones failed for various reasons, but enough survived to prove the benefits of technology. Technology provided exchanges on a platform that could let them expand their pool of buyers and sellers by shedding their physical boundaries. The merger between ICE and the International Petroleum Exchange (IPE) would never have been a success without the use of technology. DTB's use of an electronic platform showed how an exchange could list its competitor's products, expand its horizon globally, and even steal liquidity away from its competitors. 20 Traditional exchanges with a designated physical space certainly competed with each other by listing competing products in hopes of capturing market share; they could simply never do it as well. Listing new products was limited due to physical space limitations, and connectivity to capture global market share was primitive and mostly confined to telephone orders. Electronic trading models would make it easy for exchanges to list products and expand its market share around the globe. Technology began to transform exchanges around the world, and for the first time in history, began challenging the century-old floor-trading model.

Technology Advances in the Financial Industry

The electronic trading exchanges such as DTB and ICE adopted technology to create electronic trading infrastructure instead of the traditional floor-based exchanges. DTB, for example, was one of the first markets to challenge the old model for trading. Although a recent player, ICE came into the financial markets as simply an OTC market but quickly established itself as an important player in the energy markets. These exchanges took the initiative of defining the initial electronic trading architecture that would allow a successful transformation from floor-based trading model to an electronic trading model. These exchanges, along with the pioneers who took the risk of adopting electronic trading, saw tremendous growth in their exchange volume and significant increase in their market share. In the case of DTB, it became one of the largest derivatives exchanges in the world. In the case of ICE, it was successfully able to complete the acquisition of IPE and establish itself as one of the key markets in energy trading, threatening the survival of the world's largest physical commodities futures21 exchange, NYMEX. The pioneers laid the foundation for the electronic market structure and forced the established exchanges to wake up to the world of electronic markets.

As the financial markets began their journey toward electronic trading, they brought much-needed competition and innovation to the financial marketplace. The adoption of new technology has forced much of the floor-trading to extinction and brought trading screens that connect traders around the globe. By moving trading off the floor and into the virtual world, the exchanges have been able to position themselves as a global marketplace, making it possible for traders to trade virtually any product anywhere in the world. As the technology improved, the changes in electronic infrastructure accelerated and so did the competition to gain or retain market share. The pioneers have continuously improved their electronic trading architecture to provide a fast, reliable, stable, and globally scalable trading platform. The followers have leveraged the same technology used by the early adopters of electronic trading, hence reducing the time and cost of building an electronic marketplace from scratch and allowing them to catch up in the race to become electronic. New players, new markets, and new products brought an unprecedented level of changes as well as collaboration in the financial industry. New players built applications and tools to provide the financial community access to electronic markets and the trading information required to make robust trading decisions. These players began competing with each other by providing trading screens, analytical tools, risk management applications, and technology to support the electronic infrastructure. The global financial markets, including exchanges around the world, today have tremendous dependency on these new players as well as each other to build and support the electronic trading infrastructure.

The exchanges around the world are shedding their floor-trading models and moving toward electronic trading models (see Figure 1.3). The new electronic trading model has similar processes as the floor-trading model, and it continues to provide the core benefit of the exchange: a designated place where people meet to trade with each other. The electronic trading model provides the meeting place virtually, with far less human intervention.

As the financial markets began embracing technology, many of the processes in the trade cycle were automated. The army of clerks, runners, and other floor personnel are now replaced with computers. Instead of touching many hands, a trade today goes through many computers. In the electronic trading model, orders are entered by traders through trading screens, or computers automatically submit orders. Trading screens utilize programs that allow traders to view the entire market on the computer screen. 22 Black-box applications are programs developed to submit orders without any human intervention. Traders can focus on building their trading models designed to automatically submit orders when triggered by the rules built into the program, such as a price or volume or a particular news event.

These orders flow through risk management applications, which are software programs that allow a risk manager to monitor and reject trades before they reach the exchange. This process allows the trading firms to ensure traders are not taking risky positions or are not trading beyond the limits set for them. The orders then flow to the exchange gateway, which is the connectivity bridge between the trading screen and the exchanges around the globe. The orders reach the electronic infrastructure of the various exchanges through the exchange gateways. 23 The matched orders are electronically transferred to the clearing and settlement process of the exchanges.

The electronic trading model has transformed the trade cycle. Plenty of jobs have been eliminated and plenty of new ones created. The exchanges no longer rely on runners to deliver orders from pit to pit or specialists to match orders. Technology has helped exchanges automate many of these processes. It has also allowed the financial community to adopt new concepts such as risk management, which provides greater control and transparency for the trading community as well as exchanges. Technology has also allowed exchanges to provide more trade information than a specialist could ever track or provide on the floor. The electronic trading model brings greater flexibility for traders to trade more products and for exchanges to reach a far greater number of traders than they could in the floor-trading days.

The electronic trading model has also brought greater dependency among the players in the financial markets. The exchanges today depend on the new players who provide the trading screens and automated trading applications for order routing. The exchanges depend on the technology providers that provide network connectivity to support their electronic trading infrastructure. The financial markets today rely on technology for data transfer between each other. The financial market players, competitors and partners alike, continue to collaborate to standardize processes for data transfer between the players. The new players, in collaboration with exchanges, brokers, and trading firms, have continued to improve on standardization of data transfer.

Standardization

A trade touches many processes from the time a buyer and seller agree to trade. Prior to electronic trading, all these processes were done manually by humans. As the trading continues to migrate toward electronic trading, technology to transfer the trade information between parties, whether clearinghouses, exchanges, or brokers, has also seen significant improvement. The information exchange between these processes requires a common understanding of the trade cycle. During the floor-trading days, when humans processed and transferred the information, the process was standardized because there was a basic understanding of the products traded. The communication used was a common language such as English, French, or German or the hand signals used on the trading floor. When a trader used a hand signal, everyone around him understood what the trader wanted. Similarly, the clerks on the trading floor and in the back office all used an agreed-on terminology when processing the trade.

The electronic trading world is no different except that instead of humans, it is machines that have to understand the information that flows through the trade cycle. The financial market players need to collaborate to define a standardized language for the electronic trading infrastructure, to ensure data transfer and processing is done quickly, efficiently, and accurately. As the adoption of electronic trading grew, so did the standardization of messaging protocols for the trade cycle across systems. As shown in Figure 1.3, a trade passes through multiple systems, from trading screen to clearing and settlement system. Standardization allowed financial markets to define a language commonly understood by computer programs processing the trade flow.

The financial markets have spent a significant amount of time and resources in the past two decades to standardize the financial message flow. As the electronic trading infrastructure evolves, so do the standard protocols used by these electronic systems. Today there are several protocols used by the financial markets to support the full trade cycle. These standard languages are critical to the success of the electronic trading infrastructure. They allow information to flow smoothly, efficiently, and accurately between systems. They allow the financial markets to trade across asset classes around the globe by displaying the market information to a trader in a standard format and processing the order flow seamlessly. The most commonly used standard protocols in the financial industry are:

• Financial Information eXchange (FIX). FIX is a standardized protocol used for financial information processing and transfer. FIX is primarily used for front-end data processing. For example, FIX is commonly used by trading screens and exchange gateways for order flow and market data between the trading community and the exchanges.

• Financial Information eXchange Markup Language (FIXML). FIXML is an extension of FIX that utilizes XML24 vocabulary for data transfer. The use of XML allows FIX to be flexible and scalable so that it can adapt the constant changes in and additions to the financial market. FIXML allows financial markets to create standard markup protocols for various financial data. For example, Financial Products Markup Language (FpML) allows the financial industry to create standard protocols to define the financial products that are transferred across systems, or the Market Data Market Language (MDML) that standardizes the format for market data information.

• Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications Market Language (SWIFT). A standard language used primarily for back-end data processing. Predominantly used by clearinghouses and other back-office players, SWIFT provides a secure and standardized protocol to send the clearing and settlement information associated with trades.

The use of these standardized languages allows the systems to have a common understanding of the financial data transfer. Without the standardization, it would be very difficult for systems in the electronic trading model to communicate with each other. The use of standard language helps expedite the transformation of the financial market. The use of standard language makes it easier for financial market players to merge more easily. For example, two exchanges using standard language to handle trade information allows them to merge their technology faster and more smoothly since the same protocol is used to define the financial data. As the dependency on technology grows within the financial markets, it will be critical for the financial markets to agree and use one common standardized language to ensure that the market continues to reap the benefit of electronic trading.

The electronic markets have flourished. The electronic trading has allowed traders to trade in more markets and with more products. The volumes in the electronic marketplace have grown tremendously; the exchanges have added numerous innovative products and are now competing in a global marketplace. As these exchanges expand both in size and through their product listing, they must continually improve their architecture to support the growing volume while maintaining a real-time transparent marketplace. One way to ensure that the exchanges survive in the new competitive world of electronic trading is to continually enhance its electronic infrastructure. The exchange today must provide new products, handle growing volume, and support new trading strategies via its stable electronic infrastructure. The financial markets are using a very common technique that runs across many industries using technology to reform their business: outsourcing.

Outsourcing

The move toward electronic trading has brought an unprecedented amount of innovation, competition, and collaboration in the financial markets. To remain competitive in the financial industry, there is an increasing amount of dependence between exchanges and the new players entering the financial markets. Exchanges globally have used outsourcing to utilize components from a different exchange. It is now common for two competing exchanges to share technology to provide reliable, robust, and scalable exchange architecture for an optimal trading experience for their customer base while keeping the cost low. The following examples illustrate some of the technology interdependences between exchanges:

• The CBOT has utilized the electronic trading platforms of two European exchanges, Eurex and Euronext.liffe.

• NYMEX made a deal with the CME to list its entire product suite on the CME GLOBEX platform to respond to competitive threats from its rival Intercontinental exchange.

• BrokerTec utilized OM's technology platform for electronic trading.

• NYSE will utilize the Archipelago (ARCA) and Euronext technology to move toward electronic trading.

• Mexican Derivatives (MexDer) and the Italian Derivatives exchange both utilize the Spanish MEFF's matching engine.

The transformation so far has been phenomenal. The drama and excitement of the trading floor is certainly not there, but it is replaced by the excitement of transformation that will leave the financial market a different place than what it was a century ago. In the past decade, exchanges around the world have gone through the transformation to arrive at the electronic trading model used today. We share many of these transformations throughout this book, to show the dramatic and unprecedented change the financial industry has undergone. Whether it is the CBOT's journey toward electronic trading by leveraging technology of another exchange or the global competition brought by Eurex US that finally gave the wakeup call to the U.S. futures markets to move to electronic trading if they want to hold onto their market share, or the launch of the International Securities Exchange, 25 which challenged one of the oldest options markets, CBOE, by launching an all-electronic market, the experience has been unique and challenging. So, although we might miss the excitement and camaraderie of floor-trading, it is by no means a boring era for financial markets. The excitement and challenges of the transformation will most certainly keep everyone in the industry occupied for a very long time.

The Transformation of Exchanges: Basic Themes

Though the transformation is multifaceted, there are four major currents to the story: (1) the shift from floors to computer screens, (2) the shift from private clubs to public companies, (3) the shift from local and national to global competition, and (4) the shift from smaller to larger operations. We explore each of these shifts, search for the drivers behind them, and try to look forward to the various implications arising out of them. But to set the stage, let's deal briefly with each of the four trends.

Floor to Screen

For much of the last century, when exchange executives brought their visitors to the window in the exchange visitor's gallery to explain what was going on, their guests stared wide-eyed in amazement that such a teeming mass of humanity yelling at one another actually got the job done. In fact, they got it done only with teams of individuals, known as out-trade clerks, who would try to clear up all the mistakes traders made in their misstating or mishearing the price or quantity of various trades. But an exchange was a business with a big, loud, totally fascinating circus right inside the building.

The shift from floor to screen is the most visible, dramatic, and traumatic of the three shifts. It involves the shutting down of trading floors, many of which have been in use for many decades, and their replacement with computer screens on traders’ desks. In some cases, such as China, the screens have been placed on a large trading floor so that participants can walk over and talk to the people on the other end of their transactions, and the public still has something to come and look at. But more commonly, the screens are actually spread over a city, a country, or even the world, as in the case of Eurex or the CME's GLOBEX as exchanges continue to go after a larger share of the global market. It is a shift toward substantially increased efficiency, transparency, and honesty, but it is also a shift away from a system that was more colorful, rowdy, and visually interesting.

In the new world, participants can see all the bids and offers (including order size) as well as prices and quantities on prior transactions to assist in more informed trading decisions. In the new world, the trade is completed and confirmed in milliseconds rather than in minutes or hours. And in the new world, traders can translate their trading strategy into code in a black box that can fire off hundreds of orders per second.

Private Club to Public Company

In most parts of the world, exchanges traditionally emerged as member-owned cooperatives. They were a way to bring buyers and sellers together in one place, to set and enforce rules regarding trading behavior, to disseminate prices, and to create a protocol for the settlement of disputes. These mutually owned entities did a good job for their members and were often enjoyable places to hang out. But member-owned exchanges were very democratic and inefficient. In the new world of stockholder-owned exchanges, especially those that have become public companies, there is a new financial discipline and a new ability to get strategic decisions made in a very timely manner. One of the keys of the success of the National Stock Exchange of India is that it never went through a period of being owned by its members. Because it was stockholder owned, it was nimble. Because it was electronic, it was quick and transparent. Consequently, it ate the competition's lunch.

National to Global Competition

In the old days, exchanges competed with other exchanges a few blocks away or, at most, a few cities away. Until their merger in 2007, the CME and the CBOT had competed with one another for over a century, though they were always less than a few city blocks apart. Because of the regulatory and technical difficulties of trading across borders, the exchanges in other countries were never really viewed as competition.

As telecommunication costs have dropped, as electronic trading systems have made it easier to cross borders, and as regulators have become more accommodative, an exchange in Chicago or New York no longer competes only with other exchanges in its own city or country but now competes with exchanges worldwide. In 2004, both Chicago exchanges found their product lines being directly attacked by exchanges in London and Frankfurt. Mexico and Brazil have faced direct competition from Chicago in dollar/peso, dollar/real, Brady bonds, the Mexican Stock index, and the key Mexican interbank rate, called TIIE. 26 And for some time Japan has found competition from a competitor 3300 miles across the water in the form of the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (or SIMEX, which is now a part of the Singapore Exchange known as SGX).

Smaller to Larger

To grow, an exchange can develop and list its own new products and for years that's exactly what most exchanges did. Of course exchanges occasionally would copy what each other was doing, but it is usually very difficult to be successful by imitating successful products at other exchanges. The other approach is just to buy a product line by acquiring another exchange. Mergers and acquisitions occurred at a very slow pace over most of the 20th century. They have sped up visibly at the beginning of the 21st. In 2007, for example, the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) acquired futures and options contracts on coffee, sugar, and cocoa along with a large number of currencies by buying the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT) and renaming the subsidiary ICE Futures U.S. The CME suddenly acquired U.S. Treasury notes and bonds as well as grains by buying the CBOT. The NYSE acquired an electronic trading system (and a public listing) by buying Archipelago (ARCA).

These are examples of derivatives exchanges merging with other derivatives exchanges or stock exchanges with other stock exchanges. Increasingly, mergers are going across asset boundaries. So, for example, the stock exchange known as NYSE is merging with a pan-European exchange called Euronext, which combines equities and derivatives trading.

Implications of the Transformation

After we have explored each of these four transformations, we will then examine the effect they are having on the world of exchanges. We will look at how traders can now access markets worldwide on a single screen because of the work of vendors such as Trading Technologies, Pats Systems, and many others. We will examine the concept of the new modular exchange that leases a matching engine, legal services, regulatory services, marketing, product development, and other services from various vendors instead of building all that from scratch. We then turn to the field of regulation with the help of Andrea Corcoran, who has one of the most comprehensive, international understandings of regulatory issues of anyone we know. The shift to screen-based trading has resulted in a virtual explosion of new products, at least on the derivatives side of the street, and we look at how that is playing out. We then turn to an overview of the positives and negatives of these four transformations and finally end with some thoughts about where we are heading in the future.

The journey of electronic trading has not been without its share of challenges. Just like any new idea, it has gone through its ups and downs. It has endured its share of pessimists who firmly believed that the only way to conduct trading was through a floor-trading model. They believed one had to feel the market and its surroundings to make a trade and that trading in a room with just computers cannot provide the same experience. Throughout the transformation, plenty of jobs have been eliminated, plenty of new ideas have failed, and plenty of money has been lost. But the upside has also been remarkable. Electronic trading has brought the financial community closer together than ever before. There is more collaboration and more interaction between the various groups within the financial markets. The upside of the use of technology has led the floor-trading model to extinction. Screams and shouts have been replaced by computer and mouse. Member-owned exchanges are transforming into public companies and becoming global. Floor jobs lost have been replaced by new jobs created to build and support the electronic trading network. Electronic trading brought the transparency long sought by the traders. It has allowed regulators to track orders from front to back. The exchanges have seen tremendous volume increase and expanded their pool of buyers and sellers globally without any physical boundaries. Technology has connected the global financial markets, providing them with a virtual framework that will change the financial markets and the trading world for the coming century.

We will continue to see the new electronic market challenge the old models. We will see how exchanges compete with each other and with their new public company model and how they respond to the electronic platform entering the market. The changes in the exchanges have been pushing the rest of the financial markets to adopt technology to revamp their business models. It is forcing regulators to deal with challenges that are global in nature. The clearing and settlement process is undergoing renovation to keep up with the transformation of exchanges around the world. Trading firms are utilizing technology to not only innovate and improve their electronic market structure but to create and build new trading strategies and develop new trading styles. The past few years have shown the enormous success of electronic trading, and most of the players in the financial markets have accepted, either willingly or reluctantly, that electronic trading is here to stay. It is the future of financial markets. And as one trader sums it up: “Business can't succeed on nostalgia; if it's electronic, so be it.”27

Endnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10. The Stock Market: A Look Back, www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/06/alookback.asp.

11. Economides, Nicholas, The Impact of the Internet on Financial Markets, http://129.3.20.41/eps/fin/papers/0407/0407010.pdf.

12.

13. The Stock Market: A Look Back, www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/06/alookback.asp.

14.

15.

16.

17.

19.

20.

21. www.nymex.com.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27. Barboza, David, In Chicago's Trading Pits, This May Be the Final Generation, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9901E7DD153CF935A3575BC0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print; August 2000.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.