9. Building Modular Exchanges via Partnerships and Outsourcing

In this chapter we explore the radical transformation in the structure of financial markets, from monolithic exchanges that served all functions to smaller components that can be snapped together like Lego blocks to quickly build new exchanges. We provide several in-depth case studies that illustrate how various players adapted their business models to electronic exchanges.

Before the shift to screens, exchanges were built to be self-sufficient entities that supported all the functions of the trade cycle. Each exchange had dedicated groups of employees supporting the numerous functions of the trade cycle. Each exchange had its own product development group to create new products that the members of the exchanges could trade. Every exchange had an established clearing group to process trades. Each exchange also had a regulatory group to define and enforce trading rules. In essence, the exchange and its members established and supported the trading model and all the functions associated with it. Over the years, these exchanges with their simple self-sufficient model established themselves as an integral part of the global economy.

Exchanges remain a crucial part of our economy, but their organization and structure have changed tremendously. Today, the shift to electronic trading and vigorous competition among exchanges has resulted in a new, more complex electronic trading model that relies on other vendors and even other exchanges to complete the trade cycle. To compete effectively and get to market quickly, exchanges no longer have the time to build all exchange functions themselves. They needed to outsource to vendors that will give them a competitive edge. The exchanges took slightly different paths to adopt the electronic trading model. The one common theme was to take advantage of the technology built by the early adopters and the new players entering the financial markets with applications for the various components of the trade cycle. Every component could be developed by different players and the components could then be connected to complete the trading platform. For new exchanges such as EurexUS entering the derivatives market, time was of the essence. And they were able to start quickly by outsourcing major components such as exchange technology as well as trading screens and regulatory and clearing functions. For the floor-based exchange the needs were different; they had the regulatory and clearing functions, but they needed the technology to migrate off the floor.

The early adopters of electronic exchanges had to build most of their infrastructure internally. They supported and maintained all the functions of the trade cycle. The rest of the market, sometimes reluctantly, soon followed the early adopters. The followers were under pressure to catch up to the success of the early adopters. They needed to embrace technology and find creative ways to enter the electronic trading markets quickly. They took advantage of the componentized architecture of the electronic trading model. By that time the electronic infrastructure had matured, and there were many new players in the market to provide various components of the trade cycle. The migration toward a modular exchange and modular financial market began blurring the boundaries between the functions and components of trading. The electronic trading model opened up the global marketplace for exchanges to not only compete but to license technology from each other.

Modular Exchange: Building Blocks

Unlike the early adopters, the followers now had numerous choices available to build their exchange infrastructures. They were reshaping their organization using components built and supported by software vendors as well as early adopters of the electronic trading model. There were partnerships and collaborations between the exchanges. They could build their entire infrastructure by piecing components together from different players instead of building everything from scratch. The time and cost of building the entire infrastructure themselves could jeopardize their chances of survival in this fast-changing market; therefore, the modular exchange allowed them to transform quickly.

Many new players entered the market and established themselves as an integral part of the new model. The new players and their applications provided followers with the modular exchange model, allowing them to build their infrastructure in collaboration and partnership with financial market players to compete in the new global financial market model. There were over 25 software vendors providing front-end trading systems and gateways to the exchanges. More than 200 vendors offered various components, from matching engines for the exchanges to automated trading applications (black box) for traders. A number of hosting facilities provided infrastructure support and maintenance for trading firms that lacked their own technology staff. We can credit early adopters with defining the electronic trading model, but the trend to adopt the modular exchange model began with the followers, who took advantage of this competition to pick components that best suited their needs.

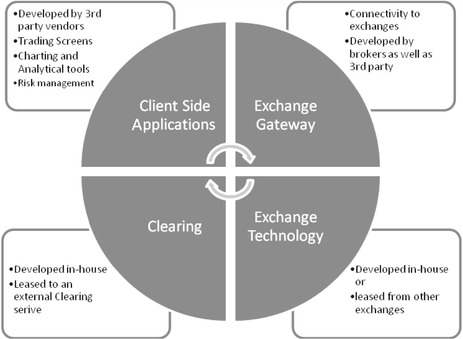

The modular exchange model extended beyond the use of technology components as the exchanges began to outsource entire functions of the trade cycle, such as clearing, settlement, and regulatory functions. The success of an exchange depends on solid services provided by all the components of the trade cycle. In the self-sufficient model, the exchanges built and maintained these components based on the needs of their members. However, the new model brought new complexity and new requirements in the trading model. To keep up with these changes, financial markets had no choice but to utilize the modular model. The modular model allowed companies to specialize in specific components to fulfill the demands of the changing model. It was far easier to keep up with the changes in a particular area than the entire trade cycle. The modular exchange model has made exchanges around the world a complex network of partnerships with dependencies on each other, far greater than in the floor-trading model. The exchanges today are a tangled web, utilizing each others’ services and technology as well as now depending on new players in the markets to serve as the gateway to their markets. To conduct trading in the new electronic trading model, a trade now goes through numerous components that could be residing in numerous locations around the globe and supported by multiple players in the marketplace (see Figure 9.1).

Exchanges no longer have to build and support every component of the trade cycle as they previously did in the floor-trading model. Instead, they now have choices available for both technology and services through numerous service providers in the financial markets. Early adopters of the electronic model who built their technology from scratch could now provide their technology components to the followers coming into the marketplace, further establishing their leadership in defining and improving the electronic trading model.

The modular exchange has in part brought competition and innovation to financial markets, and it continues to shape the electronic trading model into the 21st century. Independent software vendors (ISVs) continue to innovate in the front-end trading space. Others developing risk management tools continue to adapt and improve their applications to provide real-time risk management, and players in the back office continue to improve and innovate to provide faster and efficient clearing and settlement services for financial markets. Competition and collaboration in financial markets has flourished at an unprecedented speed in the last two decades. Exchanges today rely on these new players to build their exchange infrastructure and to expand their market base. The success of an exchange in today's model no longer depends solely on liquidity and exclusive product listing; it also depends on software and service providers. Picking the best technology and partners to build the infrastructure is an integral part of an electronic exchange.

CBOT: Cautious Migration by Outsourcing Technology

At 160 years old, CBOT is the world's oldest futures and options exchange. CBOT's transformation from the old floor-trading model to an electronic exchange provides a perfect view of the modular exchange model. CBOT, like other U.S. derivatives markets, took the first step toward electronic trading only by extending its floor-trading to after hours to capture volume in the Far East. CBOT built its own application called Project A, a second1 step toward adapting technological changes in the financial market. Project A was launched in 1994 and allowed CBOT members to trade their products after hours. The connection to CBOT markets through Project A was available via CBOT dedicated terminals scattered in numerous locations, including Asia. Traders in Japan, Australia, and Taiwan used these terminals to place orders for various CBOT products. The success of Project A initially was sporadic at best. Traders primarily used the application to hedge their positions rather than for active trading. In other words, traders who no longer wanted their current exposure overnight could cover their position. Liquidity remained low on Project A due to numerous concerns by traders in Asia, including the potential inability of Project A to process large orders and the concern of moving the market due to thin volume. For example, grain buyers in Taiwan generally traded 400 lots (54,000 tons) per order, which was considered too large to process through Project A. The volumes were far lower than that on the floor. For example, on December 1, 1998, Project A's overnight volume for agriculture futures and options was 75 wheat, 610 corn, and 413 soybean contracts compared to the next-day volume of 35,000 wheat, 54,000 corn, and 40,000 soybean. 2 However, Project A continued to serve as an electronic platform available for traders after hours. It operated every hour the CBOT floor was closed, but the volume on the exchange didn't begin to pick up until 1998, when it finally turned a profit. It saw an increase of more than 120% in volume in the first half of 1998 compared to the year before. 3

The exchange, however, was still not positioned to compete in the global marketplace. It was facing competition from new players such as BrokerTec, which was planning to launch an electronic trading platform for bond trading; the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) in 1999 was also planning to launch an electronic trading platform to trade U.S. Treasury futures, CBOT's flagship products. 4 CBOT was aware of the fate of LIFFE's Bund product and did not want history to repeat itself, especially if they would now be the victim. The exchange knew it could not compete against the other electronic trading platforms with its Project A technology. Project A was a closed platform. If a trader wanted to trade electronically on CBOT, he needed to install the Project A dedicated terminals to access the exchange. This would be a slow process for CBOT and cumbersome and expensive for trading firms. CBOT would have to continue to roll out the Project A terminals instead of providing an open electronic platform such as that for Eurex, which was available to trading firms through a number of ISVs. Trading firms that wanted to trade CBOT products electronically would need to rely on two different screens: one Project A terminal for CBOT and another for other electronic exchanges. The exchange knew it needed to either revamp and upgrade its Project A technology or form a partnership with an existing player.

Partnership with Eurex: First Alliance

The exchange took its first step toward electronic trading by forming a partnership with Eurex to outsource its trading platform module. The members of CBOT who had narrowly rejected the partnership deal with Eurex in January 1999 bowed to competitive pressure and voted overwhelmingly for the Eurex partnership six months later, on June 24, 1999. The partnership would cost the CBOT $50 million, compared to the projected $47 million cost to upgrade the Project A technology. For $3 million extra the CBOT would gain a new trading platform with global access, with Eurex's 5000 screens in 16 countries, compared to only 700 Project A terminal available in only four countries. 5

The alliance with Eurex served as CBOT's first venture into a modular exchange. CBOT and Eurex agreed to form an alliance in the hopes of increasing their global market share and consolidating the selection of products across the two exchanges. They agreed to provide each other's products on the new electronic trading platform called a/c/e, named after the Alliance between CBOT and Eurex. The partnership was one of the first transatlantic ventures in electronic trading, which would give customers on both sides trading opportunities on both markets simultaneously. Users could now trade the world's benchmark products, such as U.S. Treasuries and the German bund, through a single screen. The launch proved successful and, after the launch of a/c/e in 2000, volume on the platform grew steadily, reaching over 408,000 contracts per day by 2002. 6

Partnership with LIFFE

The 162-year-old exchange's resistance to electronic trading was beginning to show. CBOT had lost its number-one spot in futures trading to Eurex, the all-electronic German exchange, and was even falling behind its longtime rival, CME. The alliance with Eurex was successful but short lived. After a number of heated public disputes between the two exchanges over product listing rules, technology fees, and the like, the two exchanges agreed to part ways by January 2004. Once again, the CBOT needed to find a partner to provide the exchange with an electronic platform if it was going to survive in the new world of electronic trading.

The separation led to some significant strategic moves by both exchanges. Eurex announced the launch of EurexUS to compete directly with CBOT, which we will discuss shortly. The CBOT continued its migration toward electronic trading and announced its decision to lease the electronic platform from Euronext.liffe. Euronext.liffe was formed through the merger of Euronext, a conglomerate of European equities markets (Paris, Amsterdam, Lisbon, Portugal, and Brussels), and LIFFE, a derivatives market. The alliance between the two exchanges would be similar to the partnership between the CBOT and Eurex. The CBOT would list its products on LIFFE Connect, the electronic trading platform of Euronext.liffe, and Euronext.liffe would provide support and maintenance of the technology infrastructure for the CBOT. In return, Euronext.liffe customers would now have access to the CBOT products. The partnership would also offer Euronext.liffe access to the CBOT's agriculture products, which had not been successfully created by the European exchanges. The LIFFE Connect platform provided CBOT access to the large European trading community that traded with Euronext.liffe. It allowed the CBOT to take advantage of the enhanced functionality offered by the LIFFE Connect platform. LIFFE Connect was considered the most advanced platform for spread trading and options trading.

The decision to pick LIFFE Connect was met with a significant amount of skepticism. LIFFE Connect technology was significantly different from the earlier a/c/e platform developed with Eurex. For example, stop orders were supported by Eurex but not by LIFFE Connect. LIFFE Connect supported decimal pricing but not the fractional prices supported by the a/c/e platform. The two exchanges depended heavily on third-party vendors to fill the gaps in functionality to ensure that traders saw minimal impact during the transition. There were some major architectural differences that would impact the trading community when they moved to this new system. The LIFFE Connect architecture stored a trader's order book 7 in local memory on the trader's computer or server. The Eurex system, by contrast, saved the order book on the hard drive of the trader's computer or server. This major architectural difference means that if the trading system lost its connection to Eurex, the orders were restored when connectivity was regained. The LIFFE Connect system, on the other hand, would lose the order book when disconnected and it could not be restored. 8 Another major difference between the two systems was the location of the exchange matching engine. The a/c/e matching engine was in Chicago; however, the LIFFE Connect matching engine was initially located in London, home of Euronext.liffe, which was bad for Chicago traders and good for London-based traders. 9 The distance between the trading front end and matching engine impacts the speed at which orders reach the exchange. This was increasingly important to trading firms, which were increasingly using automated trading systems to implement their trading strategies.

The decision to pick LIFFE Connect also gave the CBOT its first glimpse of a truly open electronic platform and the importance of collaborating with third-party vendors, especially ISVs that were increasingly becoming the primary provider of front-end trading software. The technology was significantly different from Eurex, and trading firms needing access to CBOT would need to connect to LIFFE Connect to develop and test their software. Due to its open architecture, plenty of ISVs were already connected to LIFFE Connect, making it easier for them to provide connectivity to CBOT. These third-party vendors filled the functionality gaps by supporting stop-order functionality and fractional prices and storing the order book within their trading system. The two exchanges had only a year to complete the migration from Eurex's a/c/e platform to LIFFE Connect. The two exchanges worked tirelessly throughout the year to ensure that the transition went smoothly. During the development and testing phase, CBOT and LIFFE worked with over 50 ISVs, providing front-end trading application or black boxes for automated trading, to ensure that they were ready for the CBOT launch on LIFFE Connect by January 2004. Without a successful integration between these new players and the exchanges, the launch would not have been successful, because these vendors provided the single-screen trading concept for the exchange's customers.

The alliance with LIFFE proved successful, and CBOT saw tremendous growth in its electronic trading volume. It was now fully embracing electronic trading. By early 2004, over 60% of financial futures were trading electronically. The CBOT adapted and transformed to meet the growing demands of its users. The exchange fought the competitive battle with EurexUS by using not only its political power to lobby in Washington, but also by switching to the new technology platform, cutting costs, and slashing fees. The CBOT partnered with CME to build a common clearing link between the two exchanges, saving its customers over $1.7 billion annually through reductions in margin requirements and other clearing-related fees. The CBOT slashed its trading fees on U.S. Treasury futures almost 75%, bringing down trading fees for nonmembers from $1.25 to a mere 30 cents per contract. 10 The exchange finally saw its business turn around. It posted record volumes and successfully beat its potential competitor, EurexUS. The CBOT posted an average of 41.4 million trades for Treasury contracts, compared to a paltry 110,055 contracts at EurexUS, 11 for the months of March, April, and May 2004.

The Final Move

The exchange has not looked back since its remarkable transformation. Although slow to adopt electronic trading as the new model, the CBOT made strategic moves to slowly adopt technology and transform its 162-year-old business model from a nonprofit member-owned exchange to a for-profit exchange. It made the right decision to adopt the electronic trading model while gently easing its members into electronic trading. Since its launch as a public company, the CBOT migrated all its products to its electronic platform and began discussions of a possible merger with CME. After shaking off two takeover moves by ICE, CBOT merged with CME to form an all-Chicago exchange, making it the largest futures exchange in the world. The takeover by CME brought yet another change in CBOT's technology platform. All CBOT products would now be listed on CME's Globex platform, the third electronic home of these products.

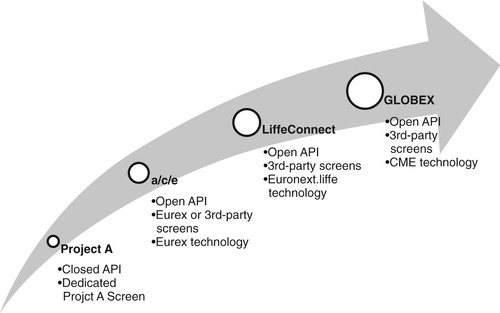

The journey of CBOT toward electronic trading shows the true benefits of a modular exchange. In the electronic trading model, exchanges can switch the underlying technology components to meet changing market needs. In less than 10 years, CBOT moved from an in-house built Project A, to Eurex's a/c/e platform, to LIFFE Connect, and, finally, to CME's Globex. It transitioned its customers smoothly to each new platform while maintaining steady growth in its volume (see Figure 9.2).

The Rise and Fall of Eurex Us: Outsourcing Technology and Services

After severing its ties with CBOT, Eurex announced the launch of EurexUS, one of the most unique launches in the new electronic trading world. Eurex planned to launch EurexUS in Chicago to compete directly with CBOT and CME, the two largest derivatives exchanges in the United States. The Chicago exchanges were still lagging behind Eurex in technology and were still struggling to move their exchanges toward electronic trading, primarily due to resistance from their own members. The move by Eurex to compete with the Chicago exchanges on their own turf forced them, especially the CBOT, 12 to make some bold moves to reposition themselves in electronic trading. EurexUS hoped to repeat history by stealing volume from CBOT's flagship product, just as it did with LIFFE. And so the competition began.

EurexUS fought through heavy political lobbying from the Chicago exchanges to establish itself as an exchange in the United States. It already had a presence there since its launch in Europe. Eurex provided remote terminals to allow U.S. traders to trade product on the Eurex platform. It had 20–25% of its trade volume coming from the United States. However, Eurex wanted to establish a U.S.-regulated exchange to gain additional market share, including the growing number of proprietary traders in the derivatives market. Soon after it announced its intention to launch a new exchange, EurexUS began to put together its building blocks by partnering with a number of financial market players to establish a fully electronic market in the United States.

EurexUS took full advantage of the modular exchange model (see Figure 9.3). EurexUS utilized the technology of its parent company, Eurex. It also adopted the Eurex market model that proved to be so successful in Europe. By partnering or purchasing products from financial market players that had already established themselves in the U.S. derivatives markets, EurexUS managed to keep its staff lean and organization efficient. By outsourcing essentially every function, EurexUS managed to run a lean shop with only 35 people on its staff, which was primarily focused on sales, marketing, and customer service. 13 EurexUS passed these savings on to its customers by offering lower fees for trading. It used the updated version of the a/c/e platform, the same platform once used by CBOT, its former partner and current competitor. It formed a partnership with the Clearing Corporation to provide clearing services for its products. It outsourced its regulatory and surveillance functions to the National Futures Association (NFA).

In addition, EurexUS formed a partnership with front-end trading system provider Trading Technologies to provide products such as TT Navigator and a smart order router. TT Navigator allows traders to view the same product from different exchanges side by side, and route orders to the best available market. This gave traders access to the Treasury products, which were listed on both CBOT and EurexUS. Traders using TT Navigator could place orders wherever they saw the best price. After a long battle to gain approval, EurexUS was approved by the CFTC to open for business in the United States. EurexUS was officially launched on February 8, 2004. The launch was successful and first-day trading topped over 15,000 contracts. However, EurexUS struggled to gain significant market share. Only four months after opening, it offered several incentive programs to entice traders to trade on EurexUS. The program worked briefly, and, in July 2004, EurexUS volume reached 40,000 contracts per day.

However, the growth in volume slowly fizzled, and EurexUS never gained traction against the bigger exchanges. A year after its launch, EurexUS managed to gain only about 5% of the U.S. derivatives volume. The exchange was eventually bought by Man Financial group in October 2006 and relaunched as the U.S. Futures Exchange.

Although EurexUS was never able to capture significant volume from the CBOT, it brought much needed competition and innovation to the futures industry. The competitive threat from Eurex forced the CBOT to upgrade its electronic trading system and provide enhanced functionality to the trading community. To keep EurexUS off its turf, the CBOT slashed its fees to match those offered by EurexUS. For example, EurexUS charged a trading fee of 20 cents, forcing CBOT to slash its prices to 30 cents for nonmembers and temporarily waiving fees for its members. 14 By shifting its clearing to the CME, the CBOT could use cross-margining15 to reduce the clearing costs for many of its customers. So even though Eurex was not able to repeat the success it had in stealing LIFFE's Bund, it managed to jolt the two monopolies in Chicago and brought much needed efficiency, innovation, and lower rates to the trading community.

More important, the development of EurexUS also showed how the modular exchange model allows one to build an exchange quickly. Eurex's technology helped establish the EurexUS exchange infrastructure. Partnerships with ISVs such as TT helped EurexUS tap into the local trading community, which was already using TT's front-end trading applications. The EurexUS launch also opened the door to the global expansion of exchanges. All one needs is to partner and collaborate with various players in the financial markets. As EurexUS proved, launching a new exchange using the modular model is easy. Gaining liquidity and regulatory approval, however, remains difficult.

Battle in the Energy Markets

Energy markets had two major powerhouses: NYMEX in the United States and IPE in Europe. Both exchanges offered similar products such as Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate (WTI). The competition between these two exchanges is very different today than in the past. As floor-based exchanges, they considered a partnership with each other a few times. In the late 1980s, when IPE failed to successfully launch its own Brent contract, 16 it approached NYMEX to form a partnership and provide NYMEX's WTI contract on their London floor prior to NYMEX opening. The proposal was rejected by the NYMEX board. The defeat prompted a relaunch of the contract in 1988. The product received strong backing by the London traders in response to the blow dealt by NYMEX. The product took off and put IPE on the competitive landscape with NYMEX. Both exchanges spent the next few years attempting to expand their territory through links with exchanges in other regions and new product launches. IPE attempted to link with SIMEX, the Singapore exchange, and NYMEX tried to expand by launching Middle East Sour Crude. Both attempts failed to gain any traction, and the volumes at the exchanges were reaching a plateau.

In the meantime, electronic trading in energy markets was picking up. Enron launched EnronOnline on November 29, 1999, and for the first time allowed energy traders to buy and sell energy contracts online. 17 The trading platform had a short life. The scandals and financial misreporting at Enron led the firm into bankruptcy, and EnronOnline shut down two years later, on November 28, 2001. Another electronic trading provider, IntercontinentalExchange (ICE), fared better. It had a slightly different business plan. The trading firms using the ICE platform were required to sign bilateral counterparty agreements. 18 A trader can see all the posted prices in the market. The ICE electronic platform had two different prices on its electronic platform: white prices and red prices. A white price means it was posted by an eligible counterparty and can be traded. A red price, on the other hand, means the trader is not allowed to trade with this counterparty. If a trader signs up for an optional clearing account, many more prices turn white.

Although ICE was successful in its short history, with over 6000 screens already available by August 2000, it knew that the lack of a proper clearing process would impact its future growth and its potential competition with regulated exchanges such as NYMEX and IPE. NYMEX was already positioning itself to take advantage of the lack of clearing on the ICE platform by listing OTC products with the exchanges clearing services. In early 2001, NYMEX announced its plan to cut margins for OTC products to compete with ICE and launched Brent futures contracts to compete with IPE. The struggling IPE and ICE decided to join forces to compete with NYMEX. On April 30, 2001, ICE and IPE announced their decision to merge. 19

The merger would give both exchanges the tools needed to compete effectively in the energy markets. ICE was able to form a partnership with the London Clearing House (LCH), which was the clearing house for IPE. IPE instantly got access to ICE's electronic platform, and both exchanges could now merge their large trading community to compete with NYMEX. In addition, ICE also took advantage of third-party vendors and their access to proprietary trading firms. It formed a partnership with Trading Technologies, an ISV for the global derivatives market. ICE granted exclusive access to its OTC products to TT's front-end trading screens. Prior to the partnership, ICE's OTC products could only be traded with ICE's proprietary Web-based application, WebICE. By offering its OTC products via TT, ICE was now available to proprietary traders who were already using TT's application to trade other markets.

The IPE floor was eventually shut down in 2004. Orders traded on either exchange were matched by the electronic trading infrastructure based in Atlanta, ICE's headquarters, and cleared in London, LCH.Clearnet's home. ICE has been fiercely competitive in the energy markets and forced NYMEX to rethink its floor-based model. Today, ICE has its own clearinghouse, which it acquired with the purchase of NYBOT. This acquisition also provided the ICE with soft commodities. ICE recently terminated its partnership with LCH to establish ICE Clearing Europe as its primary clearinghouse. Its recent decision to partner with CCorp will certainly position the exchange to gain the clearing business for products such as credit default swaps (CDS). 20

NYMEX: Outsourcing New Product Listing

NYMEX, a dominant energy exchange, was one of the strongest resistors of the electronic trading model. Like other followers, NYMEX didn't completely ignore the electronic trading model. It took advantage of the modular exchange model in 2002 when it partnered with CME to list “e-mini” versions of NYMEX's key energy futures. These products would be available for trading via CME's electronic trading platform, Globex. The product would be cleared through NYMEX's clearinghouse. The partnership gave customers of both exchanges access to products from both markets. 21 The collaboration allowed NYMEX to use CME's infrastructure and global network for its mini-products and gave CME's customers new products to trade. NYMEX and CME also worked on a joint clearing platform, CLEARING21, to provide real-time clearing and risk management for mini-products. 22

Leasing Technology

As the migration to the electronic trading model grew, so too did the adoption of the modular exchange model. The exchanges used numerous technology providers to build their infrastructure and outsourced services to established clearinghouses, regulatory services, and the like, to ensure a quick migration to electronic trading. Partnerships and collaborations within the financial industry became the norm. It is now not uncommon to see two competing exchanges cooperate to use each other's technology or services to meet the fast-changing needs of the financial marketplace.

Technology is by far the most important component of the modular exchange. Electronic trading allows the trade-cycle model to be built as components, which can be pieced together like Lego blocks. New ideas inspire competition, and electronic trading is no different. Every component of the trade cycle saw numerous players. Technology also allowed financial markets to integrate and switch between these components easily and quickly. Components from front-end trading applications to matching engines could now simply be licensed by exchanges and others to build their own electronic trading infrastructure.

European markets began the migration to electronic trading very early on. Innovative technologies such as the OM platform brought the concept of leasing technology to build the electronic exchange infrastructure to markets in Europe. As the organization and structure of the European Union solidified, the need increased to provide a financial market model accessible to all the EU nations. Exchanges in the EU nations used the modular exchange model to build an electronic trading infrastructure. Collaborations and partnerships flourished within financial markets. Today it would be hard to point to a single exchange that is based on a self-sufficient model.

Early Pioneers: Technology Providers

OMX

OMX was among the early pioneers to provide technology services to other financial firms. OMX exchanges consisted of eight Nordic and Baltic exchanges. The technology arm of OMX provided the electronic exchange platform for close to 50 exchanges around the world, across all asset classes. Prominent exchanges such as Singapore Exchange (SGX), International Securities Exchange, Bombay Stock Exchange, and Tokyo Commodities Exchange formed partnerships with OM Technology to use its electronic trading platform. These exchanges utilized the technology developed and supported by OM Technology to build their electronic infrastructure. In early 2008, OMX was acquired by Nasdaq to form Nasdaq OMX. Nasdaq OMX combines the technology and distribution network of the two giants to form the largest equities exchanges in the world, with a presence in over 50 countries.

LIFFE

LIFFE has come a long way after losing the German Bund to Eurex. The loss of the German Bund served as a wakeup call for LIFFE, which realized the electronic trading model was here to stay. It took drastic steps to transform itself by replacing its 18-year-old trading pit with electronic trading in less than two years. After the migration to electronic trading, it never looked back. LIFFE built its own technology platform, called LIFFE Connect, which it provided to exchanges around the world. It licensed its platform to the CBOT, which abandoned Eurex's platform in favor of LIFFE Connect. It is also used by the Tokyo Financial Exchange (TFX). With its merger with Euronext, LIFFE Connect became the technology platform for a number of smaller markets in Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Lisbon, and Portugal. With the recent transatlantic merger of Euronext with NYSE, LIFFE Connect became the technology platform for the equity giant NYSE.

Collaboration: Blurring the Lines between Exchanges

Many of the exchanges that resisted change did not necessarily fare badly. The technological innovations that they initially resisted actually helped expedite their migration toward electronic trading. Exchanges around the world began licensing technology platforms from other exchanges or technology providers. They had choices available to them that the early adopters did not. They could pick the best provider for each component to build a solid electronic infrastructure. Followers could also switch their platform to use different components, another advantage of the modular exchange model that allows them to upgrade their technology to suit their market needs.

There are numerous examples of exchanges large and small that depend on each other and other technology providers to complete the trade cycle. These exchanges have adopted the modular exchange model that has allowed them to abandon one platform and pick another to increase market share in the global financial markets. Through partnerships, outsourcing, and mergers and acquisition, exchanges today rely on each other more than they did in the days of the floor-trading model:

• MexDer licensed MEFF's electronic platform to build Mexico's options market.

• The partnership between Dubai and NYMEX allows Dubai to utilize NYMEX's electronic trading platform and clearing services.

• Singapore Exchange (SGX) partnered with OMX and Orc Software25 to increase its market base. Prior to the partnership, SGX provided its own front-end trading application. By opening access to its platform and utilizing third-party software, SGX hopes to increase user participation on its exchange. 26

• With its partnership with Montreal, Boston Options Exchange replaced its existing NSC-based platform from Atos Euronext with Montreal trading platform Sola.

These collaborations between exchanges are growing at an unprecedented speed as the exchanges position themselves in the global financial markets. In addition to partnerships between themselves, exchanges also partnered with ISVs that developed software to connect to multiple exchanges and provide a single-screen trading option for traders around the world. As exchanges launched new products to gain more volume or smaller exchanges hoped to increase market participation on their exchange, they forged relationships with ISVs such as Orc, TT, and more. These relationships allowed ISVs to build new features within their applications that encouraged their users to trade the newly launched products. The relationship with these ISVs also provided exchanges another marketing avenue because the ISVs, hoping to capture more market share among them, would provide users training in electronic trading and new trading styles introduced to take advantage of single-screen trading across multiple markets. Due to the technological innovations in the new model, new exchanges in today's financial markets can be built quickly. Exchanges choose and fit together components like Lego blocks, as we saw with the launch of EurexUS.

Leasing Clearing Services

The clearing function is an integral part of the trade cycle. Exchanges in the floor-trading days generally had their own clearinghouses that played the role of central clearing for the products traded on the exchanges. However, the trend toward outsourcing the clearing function is not entirely new. The Options Clearing Corporation, for example, was the government-mandated exclusive clearinghouse for all the U.S. equity options exchanges. As the exchanges migrated to the electronic trading model, the clearing service became one of the modules that could be outsourced. Exchanges such as the ICE took advantage of this outsourcing when they acquired IPE. However, because clearing generates revenue, some exchanges, including ICE, are moving to build the clearing services in-house.

Technology allowed more exchanges to list competitive products and form partnerships with exchanges around the world. Both of these moves provided a wider selection of products available for trading. By outsourcing the clearing service, these exchanges provided their customers with a central clearinghouse service. The mergers and acquisitions of exchanges, the cross-listing of products across multiple exchanges, and the listing of multiple-asset classes and OTC products have all spurred competition in clearing services. Today, as exchanges around the globe merge, the use of a common clearing service has increased, as shown in Table 9.1.

| *CBOT and NYMEX both are now part of CME Group. Both exchanges were using CME Clearing prior to their merger. | |

| **Winnipeg is now ICE Futures Canada, NYBOT is now ICE Futures US, and IPE is now ICE Futures Europe. | |

| Clearinghouse* | Exchanges Cleared |

|---|---|

| OCC | AMEX, BOX, CBOE, ISE, PCX, PHLX, CFE, Onechicago |

| CCORP | U.S. Futures Exchange (EurexUS), Chicago Climate Exchange, Financial and Energy Exchange |

| CME Clearing | CME, CBOT, NYMEX* |

| LCH.Clearnet | Euronext.Liffe, LME, APE, ECX, Hong Kong Mercantile Exchange |

| JCCH | Common clearing platform for all seven Japanese commodity exchanges |

| ICE Clear | ICE, NYBOT, IPE, Winnepeg** |

Clearing services have also seen a number of changes spurred by the transformation of exchanges. As the exchanges changed from nonprofit to for-profit companies, they had to constantly find new revenue streams to remain competitive in financial markets. To increase their revenues, global exchanges have seen tremendous growth in their product listings due to mergers and acquisitions. Technology provided tools for customers to begin trading products on multiple exchanges around the globe. These integrated exchanges and global marketplaces created demand for independent clearinghouses to clear across exchanges. Having a centralized clearinghouse allows risk management systems to consider trades across products and, therefore, customers can receive better overall margin.

However, exchanges have recently started initiatives to break away from their partnerships with independent clearinghouses to develop their own, primarily to gain the revenue from clearing. ICE recently launched its own clearing service for both the U.S. and European markets. Similarly, LIFFE announced the development of its own clearing service, leaving behind the clearing services of LCH.Clearnet. Even with these recent moves of exchanges starting their own clearinghouses, competition in clearing remains strong. There are a number of new players entering the market, such as Swapstream, which was launched as a swaps trading platform in 2003. In 2006, Swapstream was acquired by CME, which provided its clearing functions for Swapstream.

Collocation

In the floor-trading model, the pit served as a gathering place for traders to stand next to each other and trade. Being taller and louder mattered. It also mattered how physically close you were to the specialist or to the buyer or seller in the pit to ensure that your trade was executed before others. The world of electronic trading changed all that. Traders now only interact with their computer screens. Electronic trading gives the trading community the flexibility to trade from anywhere in the world. Exchanges such as Eurex and CME built their electronic success by providing remote connectivity. However, some things in trading never change. Getting a trade in before anyone else still remains important. To achieve this goal, traders now have to worry about the speed, connectivity, and proximity to the exchanges they trade on. Even if the orders traveled at the speed of light, an order submitted from 100 miles away would take slightly longer than an order from only 10 miles away. In the new trading model, having the most powerful computer or fastest connection to the exchange is a crucial criterion for successful trading.

Being close to the exchanges still matters, but the exchange infrastructure could span multiple locations. In addition, traders are now scattered all over the world. The distance between the trader and the exchange impacts the order's latency—the amount of time it takes for a message to arrive at its destination. Being first in the queue to get the order executed means having the fastest machines close to the exchange. However, traders do not want to move back to the pits. The need to achieve low latency for order submission has prompted yet another wave of infrastructure improvements.

Since traders today are not limited to a single market, the solution is not as easy as simply moving traders closer to the exchange. Instead, traders trade across multiple markets around the globe, and they want their trades to reach all the exchanges quickly. To achieve low latency across all markets, firms started moving their servers closer to the exchanges. When the CBOT began using LIFFE Connect technology, which was located in London, it potentially put its Chicago traders at a disadvantage to the traders in Europe, forcing some of their customers to move their operations to London to be closer to the LIFFE matching engine. Similarly, when IPE shut its trading floor and moved to electronic trading, IPE orders had to travel all the way to Atlanta, ICE's headquarters, and IPE traders noticed higher latency for their orders compared to traders in the United States. Firms around the world would find venues close to the exchange infrastructure to ensure that they achieved low latency. However, for firms trading across multiple markets, simply moving their offices was not enough. To achieve the same speed and low latency across all markets, companies began using hosting facilities and collocation.

Hosting facilities offered to support the technology infrastructure required to trade in the electronic trading world. They were the technology administrators for trading firms. Hosting facilities provide support and management responsibilities for network administration, hardware and software configuration, data line management, security, and backup services. This ensured that trading firms had a stable electronic infrastructure. Hosting facilities also established themselves as the solution to achieve low latency. For example, Trading Technologies’ TTNET touted its vast network, with TTNET hub computers close to the exchanges. TTNET used a global network of dedicated lines connected to gateways close to the exchange location, thus providing faster round-trip times for orders. Other hosting facilities and large investment banks offered customers similar services: a low-latency electronic trading network. These hosting facilities allowed trading firms to distribute trading screens around the world connected through these hosting facility hubs, strategically located near exchanges.

Traders are driven to compete. In the electronic trading world, traders compete with speed. As the trading community embraced electronic trading, it began to use new applications such as black-box trading applications. Black boxes allow traders to trade larger orders automatically. They allow traders to build complex strategies and let the computer execute them on their behalf. Increased automation in trading increases the need for speed. Recent research from Tabb Group estimates that to improve speed by just a microsecond costs firms approximately $250. Therefore, a six-millisecond reduction costs approximately $1.5 million. 27 The cost to achieve speed in trading has continued to increase as more players enter the market to offer ultra-low-latency solutions for financial markets. Exchanges in recent years have entered the market to provide access to their electronic platforms at low latency by offering collocation services to customers. Collocation allows trading firms to install their servers within an exchange's firewall—to have the servers right next to the exchange's matching engine in the same data center. Collocation basically allows trading firms to install their servers within the exchange's electronic infrastructure. It is the virtual trading pit. Instead of loud, sweaty traders standing shoulder to shoulder in a pit, only their servers hum softly next to each other in a cold data center.

Today, exchanges around the world offer collocation services to their customers and ISVs. The London Stock Exchange recently worked with a number of brokers to host their algorithmic trading engine inside their exchange's firewall. 28 The Australian Stock Exchange, in mid-2008, collocated its trading platform and gateway within the same facility as its matching engine, to provide submillisecond access. 29 Major derivatives exchanges in the United States and Europe have established collocation services for their customers, both to attract clients by offering low round-trip times and to earn additional revenue.

CME and LNET

CME began offering its Local Network (LNET) to customers and ISV partners, who would have direct access to CME's electronic platform. A number of trading firms and hosting facilities have taken advantage of this offer and moved their infrastructure within CME's collocation facility. In return, CME charges $6000 per connection per month, in addition to collocation facility charges. The latency with this collocation setup offers order processing time as low as 31 milliseconds for futures and 11 milliseconds for options. 30

Similarly, other, larger derivatives exchanges such as ICE and Eurex have established and offered collocation services to customers since 2006. The demand for this service has been tremendous. In a year and a half, 36 firms signed up with Eurex's collocation service, and traders saw a tremendous decrease in latency. The round-trip times went down to approximately 10 milliseconds, compared to 29 milliseconds through a connection in London. 31 Firms such as Nico Trading, based in Chicago, saw a reduction in latency from 130 milliseconds to less than 30 milliseconds when they moved their servers within Eurex's collocation facilities.

Collocation has proved crucial for market makers, trading firms using black-box trading software, and ISVs. Market makers providing bid-ask spreads for trades can get their orders in as quickly as possible, making it possible for them to beat out a market maker in another city or country. For automated trading systems, submitting large orders quickly means getting first in the queue for execution. For ISVs, it serves as a competitive advantage to attract and retain their customers. ISVs with a stable and reliable hosting facility located within an exchange infrastructure could be an attractive option for firms looking for higher speeds.

The Modern Modular Exchange

Exchanges were once large physical spaces with monolithic systems that provided all the services required for trading. The modular exchange, on the other hand, is a platform on which other companies, big and small, can specialize and innovate to build better components. Now an exchange can be cobbled together quickly by leasing technologies from or outsourcing services to vendors, which can sometimes be direct competitors. Technology quickly forced traditional exchanges to transform into electronic exchanges, and it just as quickly became a commodity that enables small exchanges to compete with their larger competitors. Exchanges can be built as though from Lego blocks—interchangeable pieces chosen based on cost, features, partnerships, speed, and reliability.

The main beneficiaries of this competition have been trading firms. Healthy competition between exchanges improves services and reduces costs. More important, a vibrant market for client technologies, such as front-end trading screens and risk management tools, allows trading firms to gain an edge on their competition. Rather than being bigger and louder, as on the floor, firms now succeed by being faster and smarter. The modular exchange model allows all market participants to excel in their niche, from the exchanges to clearers, brokers, and traders.

1.

2. Moriyama, Ayumi, “Asian Traders Hope for CBOT Project Growth,”; www.expressindia.com/news/fe/daily/19981204/33855054.html; (December 4, 1998).

3. Kharouf, Jim, “Project A Spins Off,”; http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5282/is_/ai_n24336071; (August 1998).

4. Moser, Mike, “CBOT Sees Edge with Eurex,”; www.allbusiness.com/business-finance/equity-funding-stock/295465-1.html; (August 1, 1999).

5. Moser, Mike, “CBOT Sees Edge with Eurex,”; www.allbusiness.com/business-finance/equity-funding-stock/295465-1.html; (August 1, 1999).

6. “CBOT and Eurex Hammer out New a/c/e Agreement,”; www.finextra.com/fullstory.asp?id=6133; (July 11, 2002).

7.

8.

9. North American Trading Host (NATH), the LIFFE Connect matching engine, was not launched until October, 2005, almost two years after the CBOT launch on the LIFFE Connect platform; www.euronext.com/fic/000/010/645/106457.ppt.

10. Weber, Joseph, “Chicago Takes on Europe, A Newly Revitalized Chicago Board of Trade Is Fending off Eurex—for now,”; www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/04_27/b3890096_mz020.htm; (July 5, 2004).

11. Weber, Joseph, “Chicago Takes on Europe, A Newly Revitalized Chicago Board of Trade Is Fending off Eurex—for now,”; www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/04_27/b3890096_mz020.htm; (July 5, 2004).

12.

13.

14. Weber, Joseph, “Eurex Blows into Chicago,”; www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/feb2004/nf2004025_6306_db016.htm; (February 5, 2004).

15.

16.

17.

18.

19. “Irresistible Force Meets Immovable Object,”; www.petroleum-economist.com/default.asp?page=14&PubID=46&ISS=8674&SID=325717; (Oct 2001).

20. “CCorp Unveils ICE Alliance as Fed Mulls CDS Clearing Proposals,”; www.sibosonline.com/fullstory.asp?id=19117; (October 10, 2008).

21.

22. “NYMEX Sets Daily Volume Records for Natural Gas Futures on CME GlobexÂ(®),”; http://nymex.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=890&printable; (January 31, 2007).

23.

24. “An Excerpt from a DEF 14A SEC Filing, Filed by INTERCONTINENTALEXCHANGE INC on 3/30/2007,”; http://sec.edgar-online.com/2007/03/30/0000950144-07-002932/Section17.asp.

25.

26.

27. Clark, Joel, “Co-location Services Grow While Exchanges Seek to Streamline Operations and Drive Down Latency,”; http://db.riskwaters.com/public/showPage.html?page=788665; (April 1, 2008).

28. “Feature: Colocation: A Game Worth the Candle?”; www.automatedtrader.net/feature-36.xhtm.

29. “ASX goes sub-millisecond with new co-location service,”; www.finextra.com/fullstory.asp?id=18684; (July 4, 2008).

30. Voyles, Bennett, “Co-Location Catches On,”; www.futuresindustry.org/fi-magazine-home.asp?v=p&a=1190.

31. Voyles, Bennett, “Co-Location Catches On,”; www.futuresindustry.org/fi-magazine-home.asp?v=p&a=1190.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.