CHAPTER 9

THE DIAMOND STANDARD

CREATING RETAINERS AND EVERGREEN CLIENTS

CONVERTING TO “ACCESS TO YOUR SMARTS”

This entire chapter is on retainers. That’s because these are in your “vault” on the Accelerant Curve (see page 26). Retainers provide the long-term relationships that excellent consultants deserve. Unfortunately, most consultants believe that their project’s end is also the relationship’s end.

The project and the buyer relationship are two entirely different dynamics. That’s why you should establish a trusting relationship first. It can lead to many projects and to retainer relationships. You don’t have to worry about the “active” and “inactive” clients of the previous chapter if you have perpetual clients.

And that’s what retainers provide.

Attorneys collect a “retainer” that is really merely a deposit against their ongoing (ridiculous) hourly billing in six-minute increments. (If wealth is really discretionary time, imagine entering a profession in which, in order to make money, you have to track and maximize the use of every twelfth of an hour!)

Listen Up!

A retainer is not a deposit. It is a fee paid for the value of access to your “smarts.” An attorney’s retainer is to a true retainer as McDonald’s is to fine food.

For consultants, the retainer of which I speak is a price paid for access—not days of access, duration of access, or instant access, but merely access. There are three variables that determine retainer fees, and these do not exist in traditional projects (which are based on objectives to be met, metrics to evaluate progress, and the value to the organization of meeting those objectives).

1. Who? How many people have access to you during the course of the retainer? Is it solely your buyer, or is it also two of his reports or three of her colleagues? For pragmatic and responsiveness reasons, it’s seldom more than four or so. But the more people who have access, the more valuable that access is, and the higher your fee.

2. How? Is access during business hours Eastern U.S. time, which is where you’re located; Western U.S. time, which is where the client is located; or to accommodate London time, where a key subsidiary is located? Is access solely remote—e-mail, phone, Skype, virtual meeting, and so on? Or will you be expected to meet in person at designated, mutually convenient times? The wider and more flexible the access, the more valuable the access.

3. When? What is the duration? Generally, a month is far too little, with insufficient time to test, try, respond, and review issues. A quarter is a typical minimum, but a half-year or annual retainer is not uncommon. The longer the access, the more valuable it is. (It’s often impossible for an organization to extend a retainer beyond the limits of its current fiscal year because of its own fiduciary procedures.)

When you’ve completed a project (or, better, several projects), it’s an ideal time to convert to a retainer relationship, unlike most consultants, who pack their bags and move on. Sometimes the buyer will suggest something, such as, “I wish there were a way to keep you involved here, but I have no current projects that make sense.”

CASE STUDY: The Calgon Emergency

The president of Calgon had me on retainer for five years. During the third year, which included personal visits, he called me one evening and told me that there was an emergency that required the entire field force to be assembled in Pittsburgh during the coming weekend. He needed me to facilitate the session so that it stayed on track and because I didn’t represent any internal interest group.

I changed my schedule, my wife understood, and I spent the weekend in Pittsburgh.

In the fourth and fifth years of the retainer (before Calgon was sold), the president unilaterally raised my retainer fee by 30 percent, to $130,000. “You’re more valuable than the fee you’ve set,” he said, and for only the second time in my life, I was speechless.

These are the “vault” items that create perpetual clients and eternal referrals.

Sometimes, you’ll be required to broach the issue, such as, “Gloria, I was thinking that the special relationship I have with some of my very best clients might now make sense for you.” Some clients will be familiar with retainers, and some will not. In both cases, however, you’ll have to educate the buyer about how yours works (see points 1 to 3 in the previous list).

This past year, in one of the meetings of the Million Dollar Consulting® Million Dollar Club, which I run, a very successful consultant from Australia had a fascinating insight: “I ought to stop looking at your business models compared to my own,” he said, “and start realizing that I have access in these meetings to the minds that are advising top organizations all over the world. It’s the advice, not the business model, that’s valuable.”

This same phenomenon holds true with your own clients. Their ability to access your “smarts” on a real-time, as-needed basis is invaluable. From your own observations with the client organization, you can come up with specific reasons, but here are some generic ones to consider:

• The buyer has conflicts among his or her own staff that need an objective resolution.

• There is a need for ongoing access to best practices, which you are constantly evolving from your work with dozens of clients.

• A major announcement or initiative needs to be rehearsed and/or improved before it goes “live.”

• There is confidential information and plans that can’t be trusted to internal people for discussion.

• There is an ethical issue that needs honest and disinterested analysis and debate.

• Surprises arise that take far too much time to deal with in the normal meetings or interactions, and would be facilitated by instant access to you.

Add your own reasons to my simple list. You only have to help with one or two essential decisions, problems, innovations, plans, conflicts, and so on before the retainer seems like the best bargain in the world and, as in my case study, the client is suggesting that you’ve been too low-priced!

Retainers create perpetual clients and eternal referrals. The client also realizes that providing a referral for you doesn’t endanger your priority with that client at all, since this is a very low-labor-intensity relationship. (You can handle a great many retainers, but just multiply a dozen of them by $100,000 each, and then by two referrals per month.)

Ironically, the greatest difficulty with retainers is inside your own head.

GUILT-FREE RELATIONSHIPS WHEN PEOPLE RARELY NEED YOU

I receive frequent calls from consultants who ask what to do when they are on retainer and the client has barely utilized their help. Most want to “roll over” the days and extend the duration, sort of like a competitive offer from the cell phone people.

I tell them all to do absolutely nothing, because

• The client is an adult who knows when to call and how and is making intelligent choices. The client is not “damaged,” and you are not the client’s parent.

• The value you provide is in being available and accessible. A fire extinguisher or insurance policy is very valuable in case of fire, but you still hope you never have to use them except in a particular instance and exigency.

• The reason you’re even asking is that you feel guilty and your low self-worth is bothering you. (A tad harsh, perhaps, but why else worry when a client is happy just knowing you’re there, but you’re not happy unless the client has some problem requiring your involvement?)

The value you bring to retainers (and, therefore, to evergreen clients) is in your acknowledged expertise, your accessibility, your rapid responsiveness, and your rapport and trust with the client. If retainers are the key to long-term referrals, then patience and confidence are the keys to retainers.

Listen Up!

Don’t fall into the trap where the client who is placing you on retainer actually has more confidence in you than you do in yourself.

Think about this equation: over six months, the client calls you twice, once with a minor matter, and once with a major matter. The combination of your advice and counsel results in the client’s saving a couple of days of time, making a decision with far more confidence, and avoiding a rash decision that would have required a $50,000 investment. The sum total of the tangibles is about $125,000; the intangibles provide lower stress and greater leadership mien; and the peripheral benefits are some important learning.

You’re charging a $10,000 monthly retainer, meaning that at that point, you’ve been paid $60,000 (or slightly less if it was discounted for full payment in advance). Conservatively, that’s about a 3:1 return right there.

You can’t afford (literally, afford) to equalize time and money in this relationship. The amount of time you spend talking to the client is irrelevant. The quality of your advice and the safety and comfort of knowing that you’re there are the valuable elements.

Marshall Goldsmith is the author of What Got You Here Won’t Get You There. He’s a world-renowned coach and a friend, and he was my guest at my first Thought Leadership Workshop. He and I agree completely on this phenomenon: the people whom we tend to help the most are those whom we tend to work with the least. Neither of us demands strict regimens and periodic contact.

One of the most successful people in the history of my Mentor Program—which is, in effect, a retainer, with participants having access to me over agreed-upon time frames—is currently making about $5 million as a solo practitioner. Every December, he sends in a full year’s retainer for the ensuing 12 months. We usually talk no more than twice a quarter, for about 10 minutes each time. These conversations are always on critical decisions and key pricing issues, where he solicits my ideas and anticipates client resistance, and we both work to overcome it.

CASE STUDY: The High-Tech Tremors

One of my retainer clients was the founder, with five colleagues, of a high-growth, high-tech firm. After several projects, I went on retainer. We didn’t speak often, as the firm stabilized and grew according to its strategy.

However, the client called me twice one year. Once was to facilitate a meeting with some anxious investors who didn’t feel they were seeing their return rapidly enough. Another was a phone conversation to work through the departure of two of the original partners, as painful as that was, because of a reassessment of need as the firm grew.

“For those two instances alone,” my client confided, “you were worth the price of admission.”

In Disneyland, once upon a time, they used to call that an “E-ticket,” meaning that you could get on any ride in the park at any time.

Some clients will need you often. You will have to decide whether they are having legitimate, frequent need for a sounding board, or whether you are some kind of “crutch” to keep them from falling. You want to be a coach, not co-dependent. When clients do need you often, it’s still usually a few times a month on the phone or by e-mail. Don’t make short issues into lengthy ones, and don’t allow easy challenges to become complex.

In working with a nonprofit that needed to increase unearned income, I heard a consultant say that his retainer work was currently to advise on a model to secure more donations from high-potential, wealthy individuals.

“Isn’t that a matter of building relationships between the organization’s key officers and those donors?” I asked.

“Yes,” he admitted, “that is the model.”

“Well, that’s no model, that’s common sense, and you can talk about how to go about that in 10 minutes. Don’t make things complex. That doesn’t make them more valuable; it merely makes them more labor-intensive.”

What happens if the retainer client hasn’t called? Shouldn’t you do something?! Well, yes, because your primary personal goal is to stimulate referrals for the duration of the retainer, and on an ongoing basis. So here are some practices that make sense without throwing yourself under a bus:

• If you haven’t heard from the client in a 30-day period, make a call (not an e-mail) and say that you’re simply checking in, which is your practice when you haven’t been in contact for about a month. Do not offer to do any work; just offer to listen.

• Think of the prior time the client called for help or advice, and send something additional, such as tips from other clients, with this note: “I was thinking about our last conversation and thought that this material might be of additional help.”

• Offer the client an opportunity, such as to coauthor a newsletter or blog article, that will force a response and further communication.

Your most important trait in a retainer, aside from the value and responsiveness we’ve discussed, is to be calm and guilt-free. You can handle multiple retainers, and many of us have. But you can’t do that if you’re feeling guilty about each one that doesn’t call you weekly or more often!

Bear in mind that your best clients are performing the best, have asked you for situational help in the past, and will ask you again in the future when they see the need. But by definition of being “the best,” that really won’t be all that often.

THE PICASSO RULE: YOU KNOW WHERE TO PUT THE PAINT

There is a story about Picasso’s mother telling him that he was so talented that if he joined the clergy, he would become Pope, and if he joined the military, he would become a great general.

“But instead I took up art,” he said, “and I became Picasso.”

Picasso is also most commonly cited as the artist who admonished people who pointed out that he painted rapidly and that it took him only seconds to apply blue paint, “Ah, but it’s taken me a lifetime to understand where to apply the blue paint.”

Your relationship with these “evergreen” clients must be one of that level of expert status. You must welcome the opportunity to be seen as the expert who is rarely needed, but who is invaluable when accessed. That means that in addition to not feeling guilty about your client’s infrequent contact while you’re on retainer, you must also be willing and comfortable in grasping the expert’s role with pride and not insecurity.

Listen Up!

Your value is in the unique combination of your experience, expertise, and execution. It has nothing to do with time, frequency, or duration.

Bill Russell, the great Boston Celtics basketball center who led his team to multiple championships, said in his book Second Wind that it’s not the everyday play that makes someone a standout, but rather the ability to perform at the top of one’s game when under the greatest possible pressure. He was talking about playoff games that were tied in the fourth quarter. I’m talking about the legitimate inquiries from your retainer clients who are desperate for world-class advice.

These are the fourth quarters of your playoff games.

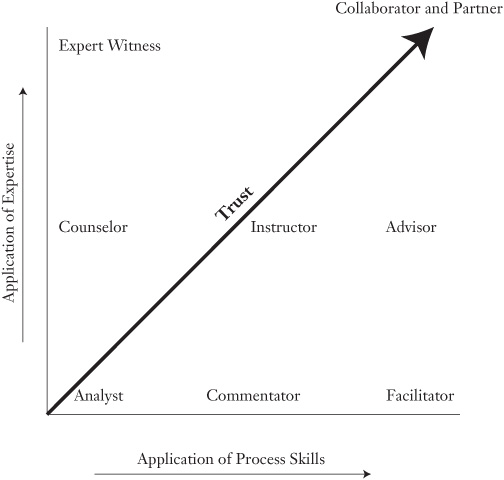

Figure 9.1 is an important aid for you.

CASE STUDY: That’s Why We Hired You

The senior vice president of human resources at Merck (a rare HR guy who was superb at working with line officers and finding them the right resources) had asked me to outline briefly how a certain internal project should advance.

I gave him three options, which is what I do in proposals, but this was a case where I was dealing with a long-term retainer arrangement.

“Alan,” he said, “we’re not paying you to tell us we have options and to choose one. We’re paying you to tell us which option is best for us.”

I never forgot that lesson, and I never confused my marketing with my implementation again.

Figure 9.1 The Roles of a Consultant

The retainer role is that of a collaborator and a partner. You are applying your native process skills (strategy, conflict resolution, decision making, and so forth) in combination with your knowledge of that client (politics, content, personalities, and so on) so as to be of particular and highly focused help when accessed. (This is why retainer relationships almost always make the most sense after a series of projects, when you have acquired that organization’s content knowledge.)

My diagonal line is the trust line, which is built on the synthesis of your best practices elsewhere and your best knowledge of that client. This is why my Merck contact in the case study correctly expected a specific recommendation—crisp and succinct—not a range of options requiring further debate and investigation. This is also why it’s so difficult for other consultants to dislodge consultants who are entrenched in retainer business—those combinations are simply too powerful to replace. In effect, the client has spent far too much educating the consultant on retainer to sacrifice that resource just because someone else comes along who claims to be better or less expensive.

The impact on referrals is enormous. As you are able to rapidly provide the articulated expertise at the right time for your buyer, your credibility and repute will grow, and people’s confidence in recommending you will also increase, since it’s clear that very little of your time is required for these relationships. There isn’t the constant fear that there is in client work that you won’t have time or will have shifting priorities.

My Mentor Program, as I’ve mentioned, is a form of retainer, and I’ve handled more than 30 active people at once and currently have more than 1,000 people in the entire program in various stages of activity. (See my earlier comments on communities that will help you to appreciate how retainerlike relationships can be managed through other people and through common experiences, with the value accruing to you.)

“Knowing where to put the paint” and being able to do so under the pressure of a close championship game are the keys to your retainer success. And your retainer success is the key to lifelong referrals. Your mindset must be that referrals are future revenue and current business is today’s revenue, and that both are equally important for your business. That’s the essence of this book, and that’s why it isn’t merely a postscript in my other books, such as Million Dollar Consulting.

I’ve come to realize this relatively late in my career, so I hope this Picasso effect will help those of you who are veterans to become even better at referral business, and those of you who are newer to gain the right habits much earlier than I did, thus ensuring your own futures at an earlier stage in your own careers.

Referrals can come intermittently from people who merely know you (or who have simply heard of you); they can come periodically from those who have been clients, especially with aggressive pursuit on your part; but they can become perpetual with little or no prodding on your part when you create retainer relationships on a large scale. These are the apotheosis of both evergreen clients and perpetual referrals. And they are the least labor-intensive to acquire and to deliver in most cases.

We’ll go on to examine how to price these retainers (since they represent current revenue, and you might as well maximize that, as well) and how to prompt their acceptance. Just bear in mind that you are creating immense benefit when you create these relatively rare relationships, and that you are cashing in on only half of the benefit if you don’t consider future revenue as well—referral business.

PRICE GUIDELINES FOR RETAINERS

Price consideration for retainers is important because you’ll be setting a precedent for your referral business. Since retainers are not based on projects with objectives, metrics, and value, they can be harder to price and to justify. Remember the three considerations for retainer fees: (1) Who: how many people have access? (2) How: to what extent do they have access? (3) When: what is the duration of the access?

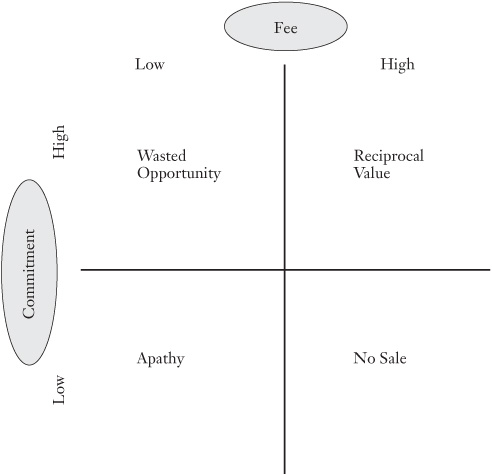

Fee setting is always both art and science, but let’s revisit the formula that represents the vital two dimensions, since we can create discipline in fees. First, Figure 9.2 shows the vital dimensions.

The more the buyer is committed and sees a high fee as justified in terms of return on investment, ego reward, and justification, the more you have a reciprocity (upper right quadrant), meaning that the buyer finds you valuable and you find the buyer valuable. If the buyer is highly committed to your worth, but you don’t charge sufficiently, you’ve wasted the opportunity. Obviously, if buyer commitment is missing (below the horizontal line), you’ll have no sale or a poor sale. These aren’t going to result in retainers.

Figure 9.2 The Fee/Commitment Relationships

So the buyer has to believe in the value of the access to your smarts, something that is most easily provided and established through the great return on prior engagements and projects, which is why retainers seldom are the first relationship you have with clients (unless you have a sterling brand and great intellectual property, such as highly regarded commercial books).

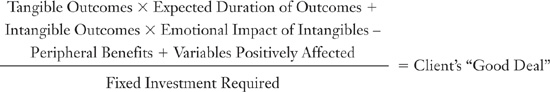

Then there is the “formula” that we can apply to retainers as well as to projects that provide direct and indirect benefits (see Figure 9.3).

In a retainer, the tangible outcomes would include immediate applicability of the advice, rapid change in the situation, problem quickly solved, decision immediately made, conflict rapidly resolved, and so forth.

The intangible outcomes might include stress relief, warring factions defused, increased confidence in decision making, precedents set, future decisions made at proper levels, and so on.

The peripheral benefits would be represented by greater confidence in the buyer’s decisions, increased appreciation by the board, transfers of skills, knowledge that events will be quickly reconciled, and so forth.

As you consider these factors, we’ll add to the “art” of the art and science. (1) Why you, why now, why in this manner? If a great many people could provide this expertise and responsiveness under similar circumstances, then you’re less valuable. But if you are alone in that capacity, you’re very valuable. And why now? Is there a window of opportunity or a period of threat that makes your counsel more critical than at any other time? And why in this manner? Has your buyer attempted this before with others or internally and found the process to be weak? Does your position and repute represent the “last best chance” (to quote Lincoln)? (2) Your buyer’s ego is at stake. Buyers don’t usually say, “I have the cheapest consultant on retainer I could find,” or “I’ve decided to retain that guy who did so poorly on projects here so that he can screw up still more.” Instead, they say, “Joan is very expensive, but her work for us and other world-class companies has been so outstanding that I’ve decided we must retain her as we embark on these challenging times.”

You get the drift. In addition to the tangible, intangible, and peripheral benefits, there is a question of your uniqueness and the buyer’s ego. All of these factors provide weight for your actual retainer fee.

Having established all of that, and while encouraging you to be aggressive in your own unique situations, here are some criteria to help you out.

First, the retainer arrangement should be for a minimum of three months (a quarter of a year). There is insufficient time in shorter periods to allow for the ebb and flow of buyer needs, for trial and error, and for experimentation. Monthly retainers make no sense to me for that practical reason alone. If the buyer doesn’t use your help in a month, the party is over.

Second, the limit on the number of people from the client who have access to you in a retainer relationship should be three. If you’re truly accessible without limit, then you can’t afford to have too many people from a single client. Moreover, you must ensure that all these people are of about the same level, such as the CEO and two direct reports, or three line vice presidents.

Third, payment terms should always be at the beginning of the period, with an incentive if needed. In other words, a 90-day retainer is due and payable at the outset of the 90 days, a half-year retainer at the outset of the half-year (perhaps with a 10 percent incentive for full payment), and so forth. Allowing for monthly payments is leaving the door wide open for a minion in accounting or procurement to point out that, since no contacts were made over the prior 30 days, no payment should really be due. These low-level people don’t think in terms of the value of your being there, but rather in terms of boxes on grids being filled in.

Fourth, the retainer should never be for less than $5,000 per month as an absolute minimum, and that probably only for smaller businesses. Given the previous criteria, I suggest that your fees be at a minimum of $7,500 per month and up. Retainers of $25,000 per month are not uncommon at senior levels of Fortune 1000 organizations (former executives are often pulling in six figures per month on “retainer” arrangements).

Don’t accept monthly payments and provide incentives for longer periods, so that a $10,000 monthly retainer becomes only $100,000 for the year if it’s paid in full on January 2. In the case of a true emergency—such as an executive’s illness, a company disaster, or sudden resignations—I do allow retainers to be extended, but only if payments are made as originally agreed.

RETAINERS FOR LIFE (AKA “THE VAULT”)

We’ve reached the extreme right of the Accelerant Curve, which I’ve reprinted in Figure 9.4. This is the “vault” area, which is beyond “breakthrough” and is your personal turf and domain, with unique value to your client.

How do you create what are, in effect, “retainers for life”? How do clients become permanent and perpetual, providing an endless stream of referrals and endorsements?

No single client will probably ever be permanent. I’m sure you can cite an exception or two, but even Peter Drucker didn’t work with General Motors continually (although he might have literally invented strategy as we know it while working with Alfred P. Sloan there).

The key (combination?) to the vault is to have a large number of retainer clients so that they are replenishing themselves or being replaced by newer ones. Retainer clients can

Figure 9.4 The Accelerant Curve and the Vault

• Be with you for many years.

• Leave and come back.

• Drop out permanently.

• Be replaced by newer retainer clients.

When you hear a choir sing an especially long note, it’s because some members are sustaining it while others take a breath, then others sustain it while the first group takes a breath. What the audience hears is a single, lengthy note that was continued through collaboration.

What you can achieve are “permanent” retainer relationships created by an overlap of those coming, going, and returning. It’s vital that you maintain a sufficient number of retainer clients to “hold the note.”

View your client list as a cumulative one, where you want to maintain a certain critical mass of concurrent business, not merely sequential business.

In looking at Figure 9.4, you can appreciate that as you take clients through projects down the Accelerant Curve, it is easier to create retainer relationships. However, as your brand and your thought leadership grow, you will also derive the “parachute business” on the right, which might immediately begin as retainer business.

I’m suggesting that this “diamond standard” of evergreen clients needs to be nurtured, fed, and pruned, so that while there may be turnover, there will always be a critical mass present. And that critical mass will be producing passive (unsolicited) referrals for you on a figurative round-the-clock basis.

CASE STUDY: We Need Smart People Here

I was introduced by a subordinate (I was referred to the subordinate by an existing client, and she paved the way for me to meet her boss) to a senior vice president at Marine Midland Bank (now a part of HSBC). Over the course of our allotted 45-minute meeting, I rather desperately tried to figure out a need that was being expressed that I could help meet.

The vice president was cordial and open. He apologized after 40 minutes, saying, “I’m sorry that time went by so quickly, but I must go to another meeting. Call me next week and we’ll set up a relationship with you so that you can help us.”

Happy but bewildered, I blurted out, “Help you with what?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said, “but I do know we need smart people around here, and you’re smart, so we need to find a way to keep you around and have access to you.” (I went on to work for this individual in three successive organizations he joined.)

If your doctor has 300 patients, 10 percent of them refer new patients to her, and 2 percent leave because of death or relocation, then the doctor has 324 patients at the end of that year. If the same proportions continue to hold true, then the next year the doctor has 350 patients. Doctors routinely receive passive referrals from happy patients, and many of the finest general practitioners today (individual care physicians) don’t take on new patients except by referral. They are renewing their referrals and their patient numbers without trying.

The same holds true for consultants.

You can sustain that long referral “note” by focusing on retainer business, which is the business that is most likely to provide you with passive referrals. “Out of sight, out of mind” is more than an observation—it’s a threat. And absence does not make the heart grow fonder; it makes the brain forget.

Project-based work that expires and leads to disengagement can be effective in providing referrals during its life, but not as much after the projects end. Retainer business keeps you omnipresent, even if you’re not actually contacted daily (or even weekly). The client knows you’re there, and you can readily raise your profile at whatever point you like.

Most consultants have not looked at retainer business as a natural evolution from project business, nor have they considered the cumulative effect of concurrent retainer clients.

Now that you are on board with these concepts, let’s turn to the disciplines you can apply to create round-the-clock referral business.