CHAPTER 2

THE ANNUITY FACTOR

I WILL STILL LOVE YOU IN THE MORNING

CREATING A MILLION DOLLAR CONSULTING® ACCELERANT CURVE

The Million Dollar Consulting© Accelerant Curve is designed to give you some guidance on how to attract the type of clients and perpetual referrals that are best for you.

The vertical axis in Figure 2.1 is decreasing barriers to entry—that is, making it easy to know you and your work and results. The horizontal axis is increasing fees, which result from higher value and increased intimacy with you and your work.

Solely considering those two axes, you can see that the easier it is for people to appreciate your work, the more people will seek more of a relationship and more intimacy with you, moving, for example, from free downloads on your site, to the purchase of products, to participation in a teleconference, to registration for a workshop, to personal coaching, to consulting work, to retainer, and so on.

As a client “slides” down the Accelerant Curve, trust and branding grow commensurately. Along the way, “bounce factors” can speed things along (for example, someone reads one of my books and decides to make a “leap” into my Mentor Program). The verticals you see representing your offerings (no matter what type of business you’re in) tend to be competitive on the left (most people offer something similar), distinct in the middle (there are distinguishing features about you), and breakthrough toward the right (only you provide such products and services).

Figure 2.1 The Accelerant Curve

Eventually, you have what I call a “vault” that houses your unique offerings, which may include retainers, licensing, electronic applications, and so forth. As your brand and your reputation increase, “parachute business” is drawn directly to these high-end, high-value, high-fee offerings without the necessity to proceed down the Accelerant Curve. At these points, one’s entire Accelerant Curve may shift to the right, with a higher fee required for entry even on the left, because of your reputation.

There is no magic number of verticals, but take a few minutes now or when you finish this segment or chapter to define how many offerings you have and how they are distributed. Too many people are focused solely on the left, the middle, or the right. That means there are “chasms” and clients can’t easily increase their work with you gradually over time. You must have a diversity of offerings in place, spread along the curve, and manifest so that your prospects and clients can readily identify them with you.

That means that you speak about them, publicize them, write about them, mention them in conversation, gain testimonials about them, and so on.

Listen Up!

You can’t be a one-trick pony, or the only referrals you’ll receive will be for that one trick.

If you find you have gaps, determine how you’ll fill them in.

Ironically, as you move from left to right, labor intensity usually declines. That seems like a paradox, since value and intimacy increase. But you’ll find that people are quite happy with relatively brief moments if they know they have access; electronic and “remote” abilities can create very rapid responsiveness; and merely the fact that someone knows you’re there (for example, on retainer) carries great comfort.

The lessons for referral business include these:

• As clients progress down the curve, they are capable of providing referrals for everything that has preceded the place where they are. Never be content with a single referral for a single offering, or merely with “character references.” It’s far better to have someone say, “If you’re looking for the best strategy implementation expert I know . . . ”

• Make sure you “seed” your events and promotions with existing clients who are far down the slope. For example, if you host a breakfast for 15 prospects, make sure you have at least 3 clients among the group. They will sing the praises of all that they have been through far more credibly than you can. (One of my favorite clients is someone who walks through a room of peers saying, “You must engage in this experience with Alan. It’s changed my business. You can’t wait. Do it today!”

• Accelerate “vault” business by focusing on referrals from your very best customers and clients. Don’t spend too much time with referrals from the left, “competitive” side; focus on those who took the leap and engaged you in high-value work right from the outset, and who can encourage others to do so. The Accelerant Curve works nicely on its own, but your prompting should always be for “breakthrough” relationships.

• Choose a point on the curve—say, a third of the way or halfway over—when you ensure that you’re following the earlier advice to begin the serious request for referral business. Let that be your “trigger” point.

I hope you’re beginning to appreciate that a client’s value to you is more than merely the total of the cashed checks and credit card receipts. And the strategies and tactics for building long-term referral value can be an intrinsic part of your client interaction. You can methodically include referral building almost from the initial point of contact, but certainly from designated points that you create along the way. The more valuable the client, the more this is vital.

Whether you choose to use the Accelerant Curve or not (although I can’t imagine why on earth you wouldn’t), you’ll need some metrics to help you judge when to maximize your ability to garner and utilize referrals from the most valuable sources. The “physics” of fees are simple: it’s far better to have one $100,000 client than ten $10,000 clients—profit margins are higher, and labor intensity is far lower.

Once you’re adept at this, the question now becomes how best to create that referral from the individual who can best provide it. Companies don’t give referrals, people do.

The onus is on you to decide how you’ll deal with each buyer and significant potential referral source.

ADJUSTING TO THE STYLES OF BUYERS

Buyers, who are also our chief referral source, have a wide variety of styles, as do we all. I haven’t experienced an “ideal” leadership style, for example. My experience points more toward leaders being successful by being flexible in dealing with others, but also being consistent about how they handle key issues. (In other words, acting the same about ethics or urgency or opportunity, and not being situational and unpredictable.)

I’ve seen buyers who are aggressive, friendly, authoritative, consensus building, analytic, and highly risk taking. They can all be successful or unsuccessful, and they can all be strong referral sources or weak referral sources.

It’s incumbent upon us to adapt to the style of the buyer (or any other referral source that you want to include—I’m simply focusing on the most obvious, frequent, and important one here). We’ve already discussed timing and preparation in terms of alerting the buyer that you’ll be asking and providing guidelines for timing. Assuming that you’ve done all that well, here are some techniques based on varying types of referral sources.

1. The Validator

This is a person who is happy, but who wants to “wait to see what the final results look like.” The problem is that “the final results” in this person’s mind can be years away! The resolution here is to focus on the objectives and metrics of your project, and point out that certain interventions have certainly proven their worth.

Example response: “Would you agree to provide some referrals based on the fact that the first six people coached have already shown higher average new business sales after just 90 days? We know that to be true, and I’m sure you know some people who would be delighted with that result for their own operations.”

2. The Skeptic

Ironically, the greater the short-term success, the more some people are prone to question whether you were really the key cause of the improvement! When you exceed expectations dramatically, you can find yourself in the unlikely position of being “too good.” You need to demonstrate your exact contributions and the etiology of the intervention and the result.

Example response: “I worked with the members of your top team for 30 days, after which they are holding only half as many meetings, and you have indicated that the requests for you to ‘referee’ amongst them have disappeared. Obviously, if we hadn’t changed things, the old behaviors would have simply persevered.”

3. The Disclaimer

Some buyers will tell you that what you’ve done is so unique that they really can’t think of anyone else who can use your help. They will “give it some thought,” but they’re really at a loss as to whom to recommend. (This may be real or an equivocation, but it doesn’t matter.)

Example response: “Let me offer some suggestions. You’re running a subsidiary, as are four of your colleagues. Although the content is different, the process of strategy implementation we’ve used can be applied to each. Why don’t we start with those four? Would you introduce me?”

4. The Collector

This buyer doesn’t want to share you. In the previous chapter, we discussed the real fear of losing your priority attention because of the volume of business you have, and the irrational fear of helping internal competitors.

Example response: “I’ll guarantee you the exact same level of attention and responsiveness you have with me now, but surely you can respect my own need to grow my business so that I can develop more resources to help you still more? Can you cite me an instance in which your own operation turned down business because you might have too much?!”

5. The Delayer

For many people, any issue that isn’t directly affecting them is, by definition, low priority. People will procrastinate by saying, “Just give me a little more time.” They’re often quite sincere, but they’re also quite frustrating in that the “little bit of time” becomes an eternity.

Example response: “I know how busy you are, and I also know that you do have some very good prospective referrals for me. Let’s just talk through them right now, while we’re already together (or on the phone; never by e-mail). Can we take just three minutes to name four or five people? For example, what about . . .?”

6. The Superficialist

To your immediate gratification, you receive a dozen referrals when you ask. But as you begin to pursue them, you find that they are at the wrong level, are not really known to the originator, have no relevant need, and so on. You have quantity but not quality.

Example response: “After I spoke to a couple of the people on your list, I realized that I’ve made a small mistake in not explaining carefully what makes sense for all of us. The people I need to talk to are people like you: at your level, in need of this kind of value, and personally known by you. Can you help me sort out the rest of this list or add people to it?”

7. The Jurist

You’ll sometimes hear, despite earlier inquiries from you about potential, “I’ve double-checked with our legal department, and it turns out that I really can’t give you referrals because of competitive situations, liability, and so on. I never realized it would be this difficult.”

Example response: “We have several options here. For example, you can give me personal referrals, such as people from your club or your social network, not at all connected with the company. Or you can simply give me some names without an introduction and allow me to say that I know you and have worked with you, without disclosing any content. Or you can give me names with the provision that I won’t use your name at all. Which of these can work?”

8. The Unreachable

On occasion, you’ll find that calls and e-mail on this subject are not returned, even though you speak with the buyer about other things, and despite the fact that the buyer has previously said that referrals are fine at some point. You need to be more aggressive here.

Example response: “Alan, while we’re talking about the great results of the restructuring, I thought of three people I want to run by you as potential clients for me. You know them all, and I’d like to use your name and perhaps even obtain a personal introduction.” (This is bold, but you have nothing to lose at this point.)

Prepare yourself for these contingencies. And don’t forget, these are exceptions. If you’ve prepared the proper groundwork, most referral sources will proactively say, “I have another couple of people you really ought to meet. When can you call them?”

WHY AND WHEN PERCEPTIONS OF VALUE FOLLOW HIGHER FEES

The mantra in professional services is that the higher your value, the more you can charge. (If you’re charging by the hour or the day, or in six-minute increments as attorneys do, stop reading immediately and pick up Million Dollar Consulting or Value-Based Fees. Otherwise, you’re not going to appreciate what follows.)

If you see a progression from competitive, to distinct, to breakthrough in your offerings, you can understand how the last is worth more than the first two. Thus, coaching a midlevel manager is something that gazillions of people can do, but forming internal accountability groups to perpetuate growth every day is much more distinctive, and providing unlimited access to you by e-mail and phone for external support is breakthrough. (This applies to everything from buying a car, where the salesperson uses a “configurator” to allow you to design the car on the computer and see the results, to pizza delivery, where some operations guarantee delivery in 40 minutes or it’s free. There is always a way to distinguish yourself, your products, your services, and your relationships.)

The fascinating aspect, however, is that “breakthrough” perceptions are often created by the very act of raising fees significantly above those of the competition.

Think of Brioni, Bulgari, and Bentley, three of my favorite “Bs.” You don’t need them in order to dress well, tell the time, or have effective transportation. But because of their perceived excellence, cachet, and ego satisfaction, they can charge whatever they like. (Before the entire automobile world changed, GM would tell its designers that they had to create a Buick that would sell for $18,000 and provide the company with a margin of 20 percent. Mercedes would tell its designers to build the safest, best-performing car they could; once it had the car, it would then decide what to charge for it.)

Figure 2.2 shows a relationship I’d like you to consider.

In the graphic, as time goes on and your reputation and brand improve, the lines cross. You’re now perceived as being so strong and influential in your field that the very fact that you can charge as much as you do indicates your quality. It does seem paradoxical, but think of your own purchases. Many senior people love to brag that they have the best coach money can buy (along with their Baume & Mercier and their Mercedes).

Figure 2.2 When Value Follows Fee

The lines cross when your brand becomes so strong that it attracts people to you, making fee of little concern. That is also the point with the strongest gravity for referral business. Your clients actually love to give your name to others because this magnanimous act shines favorably on them, as well. After all, they found you, have utilized your help, and have been able to afford you.

What takes you to that point? Where do your lines cross? Here are some suggestions:

• You are providing thought leadership in your profession and/or niche. People see you as one of the highest authorities in your specialty.

• You pump intellectual property into the environment. You are a source of new ideas and techniques that are pragmatic and applicable for your clients and prospects. You turn intellectual capital (theory) into tangible application (intellectual property). This process is known as instantiation.

• You are an object of interest to others. You do things and attract people that are exciting and newsworthy.

• You use clever phrases and metaphors. I often cite my TIAABB (there is always a bigger boat) to demonstrate why people shouldn’t merely always try to obtain the “biggest” or the “most.” Your models and methodology are memorable.

• There are significant peripheral benefits from using your services. There may be private newsletters, dedicated websites, global chat rooms, “hot lines,” and the opportunity to meet peers who themselves are of great interest. Your clients actually improve their brands by citing their relationship with you.

Referrals flow best downhill. That is, the greater the gravitational pull, and the fewer the bumps, logs, boulders, and obstacles in the way, the faster and surer the referrals. When you create very strong brands, you create that steep slope.

What you should be becoming familiar with in these opening chapters is that Million Dollar Referrals are not “average” or “usual” referrals. They rely on special kinds of clients (or others) and special kinds of relationships, fostered by your reputation and your accomplishments.

Listen Up!

The ultimate brand is your name. You can have a multiplicity of brands, but you can’t beat someone saying, “Get me Anna Smith” in the same way people once said, “Get me IBM” or “Get me McKinsey.”

Just as you’d want to pursue clients who represent high potential fees and ongoing business, and who have a tradition of using external help, you would also seek those individuals within clients who can provide the most dramatic, effective, and long-lived referrals. The more well known you are, the more you can charge, the more you can legitimately promote your successes, and the more you can expect to gain dramatic referrals from clients.

Here’s one of the underlying secrets: when people pay a lot, their expectations are high, and their own propensity to fulfill those expectations is high. That’s right, someone relatively unknown would have a tougher time influencing a tough, high-level audience. But someone with the reputation for thrilling these audiences and challenging them will find it easier to thrill and challenge them!

In other words, when you’re rolling downhill, you keep picking up momentum.

THE CLIENT POTENTIAL BELL CURVE

It’s one thing to talk about finding and retaining high-value clients, but how does one do that with efficiency and effectiveness on a continual basis? At first blush, any client who is interested is a good client! When you have to put bread on the table, such interest becomes extraordinary.

Yet professional services providers spend far too much time on low- and medium-level prospects, allowing themselves less time to acquire the true high-priority prospects. When I was a kid, there was an apparatus in the playground called “monkey bars.” The objective was to hold on to the overhead bars and traverse them to the other side, using only your hands, with your feet dangling. (I’ve learned over the years that these things existed all over the world; such is the culture of play.)

I would grab the first overhead bar, peer down at what looked to me like a thousand-foot drop, and cling for dear life. Inevitably my arms cramped, and I fell the two feet to the ground. Some of my friends, however, raced across, counterintuitively letting go with one hand to reach out to the next bar. That’s the first time it struck me that you had to let go in order to reach out.

The identical phenomenon applies to all of us today. You can’t reach out (to new, high-priority clients and referral sources) if you refuse to let go (of current, low-priority clients and the pursuit of more of the same). As I watched consultants—even very fine marketers—continue to indiscriminately pursue eclectic prospects, I wondered how to rationalize the process.

I compared what I was doing to two other highly successful thought leaders: Seth Godin (Purple Cow, amongst other books) and Marshall Goldsmith (Mojo, amongst other books), and I discerned what people with strong brands have tended to do.

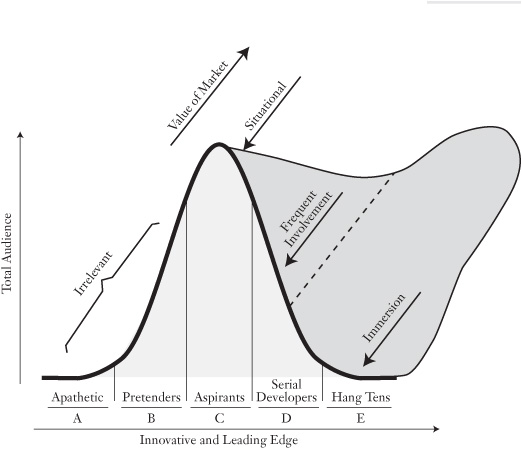

We are operating at an extreme of the normal distribution of clients because we see that distribution (intentionally or unintentionally) in a third dimension. Take a look at Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Market Value Bell Curve

The left axis is the total constituency you can expect for your products and services, without restriction. Too many people will tell you that their audience is “everyone,” but that’s simply never true. However, many professional services providers can have quite large potential audiences if there are no restraints, as we’ll see in a moment.

The horizontal axis is how innovative and leading-edge the potential audience is. Thus, in this distribution, as we move from left to right, the categories are

• Apathetic. These people may nominally be prospects, but they do not care about such offerings from anyone. They may be unprepared or simply arrogant, but the result is the same.

• Pretenders. People in this audience segment act as if they are serious; they may attend association meetings and pay lip service to development, but they are seldom purchasers of substantial help.

The first two segments are irrelevant in terms of soliciting high-value clients and referral sources.

• Aspirants. These are more serious prospects in terms of considering your offerings, but they are very situational. Your appeal to them may depend on timing, circumstances, or peer pressure.

The third dimension of the bell curve begins to be meaningful from this point on.

• Serial developers. These are people who are serious about their own development and that of their people. They will regularly engage in hiring external help, although they tend to budget for it, compare offerings, and plan carefully.

• Hang tens. From the old surfing lingo, these are prospects who take prudent risks, want to ride the toughest waves from the front, and are very early experimenters. They will seek out people with novel and/or widely discussed innovative methodologies (hence, the appeal of strong brands and intellectual property). These people can be totally immersed, with their organizations, in your approaches.

Listen Up!

Not all prospects are equal. You must consider the quality of your constituency, not merely the volume.

I’ve labeled these A to E because of the old ticket system at Disneyland, where the “E ticket” was the one that gained you access to the best rides.1

My advice to all professional services providers—particularly those with established firms and practices, strong brands, and evolving intellectual property—is to consciously and deliberately focus on penetrating the extreme right-hand side of my bell curve. The value of the market you serve is reflected in that third dimension, but we’re too often lulled into pursuing leads in the middle and on the left because they are easier—people who merely inquire, can’t buy, are trying to show they are players, and so forth.

The annuity factor in referrals is complementary to the annuity factor with great clients. Those that are smart, successful (they have money), and eager to lead the pack are the best bets for both. The hang tens I’ve described are those who are very eager to invest in products and services that will enable them, personally, to excel and their organizations, as a whole, to create market dominance.

Capturing 20 percent of the D market and 10 percent of the E market is hugely more important than acquiring 50 percent of your personal A to C markets. The revenue per client will be higher, the repeat business rate will be higher, the rate of referrals will be far higher, and the quality of those referrals will be significantly higher. Just as a single $100,000 project is more profitable and less labor-intensive than ten $10,000 projects, so too will the value of the referrals be that much higher in those circumstances.

ALLOWING THE BUYER TO BUY (MORE AND MORE)

Before we leave this topic of “annuity clients,” I’d like to reinforce the fact that buyers buy. That’s why we call them “buyers.”

The idea is to not get in the way.

That sounds ridiculously obvious, but my experience highlights the exact opposite: too many service providers louse up their own sales, their own credibility, and their own value by impeding the buyer’s ability to buy.

Here are the key factors.

1. Never “Pitch”

You’re a peer of the buyer. Peers don’t blatantly sell to one another. They recommend and suggest courses of action that can legitimately assist their peers. (Trust is the fervent belief that the other person has your sincere best interests in mind.)

The stereotypical “elevator pitch” is one of the stupidest pieces of advice in all of salesdom (similar to the “imagine the audience naked” among professional speakers). It’s so colossally stupid that I scarcely know where to begin with it. But I do know that I don’t like to hear a sales pitch that I didn’t solicit, particularly on private time. I’d stop the elevator, throw the barker off, and resume my vertical trip.

No matter where you are—in an office or a conveyance of any kind—don’t become a trained seal. People might laugh at you, but they won’t jump in and hunt squid with you.

2. Eschew the PowerPoint®

Whenever I see a PowerPoint (or similar technology) presentation, I think of timeshare salespeople or intrusive Web popups. Technology has a way of superseding the personal relationship (which is why this is deadly in speaking, because the attention is on the technology, not the speaker).

CASE STUDY: The Partner Meeting

I walked into a meeting of four partners in a start-up that was seeking a consultant. They each had a favorite, and we were called in separately to chat. I walked in with only my Filo fax® diary and placed it on the table.

I saw the vice president of sales hand the CEO (my contact) ten dollars. I learned later that the CEO had bet the other three that I’d be the only one not making a formal presentation and would, in fact, have minimal material of any kind.

They gave me the job.

The more technology you use, the more high tech you place in the way of high touch.

3. Focus on Creating a Trusting Relationship

Ironically, paradoxically, the longer you take to establish a trusting relationship, the more quickly you will acquire high-quality business.

Too many professionals want to waltz in and depart with a contract in their arms. It’s not in the cards. If you think of the hang tens discussed earlier, you may be able to achieve a faster relationship with them because of their predisposition to try new things rapidly, but a relationship is required, nonetheless.

4. Stop Abandoning the Buyer

Here are two things you never need to do:

1. Go out and gather data for a proposal on your own.

2. Go out and meet people because the buyer asks you to do so.

If you’re dealing with a legitimate economic buyer, you have everyone who’s required to create a quality proposal in the room: you and the buyer. If the buyer insists that you talk to others for “background,” immediately set a date for the two of you to debrief once you’ve done that and reestablish your partnership.

Always inform the buyer that others are likely to be threatened by the kind of change you’re proposing (or the buyer is requesting), and that the decision is probably a strategic one that the buyer should be making independent of tactical people.

Listen Up!

There is a reason that the buyer is talking to you. The buyer is interested to some degree. That’s a plus. Don’t mess it up.

5. Don’t Provide or Accept Arbitrary Alternatives

When the buyer says, “We’d like you to give us a proposal for a three-day, off-site leadership workshop,” your only reply should be, “Why?” The buyer has provided an alternative for you to fill. But what’s the objective? Why shouldn’t you examine the goal before being part of the route?

Similarly, don’t lead with your methodology: “What you need is our six-step Accelerated Sales System (ASS).” The client may need only Steps 3 and 6, or a seventh step as well, or none at all. Ascertain the real need and the desired end result, and work backward from there.

Hundreds of thousands of consultants have lost billions of dollars because they’ve either accepted a completely unilateral client request or tried to fulfill a legitimate request with an ideology—a fixed methodology.

I’ll conclude this chapter and this last topic about allowing the buyer to buy by addressing nonbuyers and nonclients. How do you allow them to “buy into” your worth and value and spread the word for you while offering contacts?

These people are most often

• Professional acquaintances (accountants, doctors, lawyers)

• Social acquaintances (friends or people with shared interests)

• Association colleagues (trade and professional associations)

• Civic colleagues (those on commissions, boards, and task forces)

• Interested others (people who know of your work or buy your products)

In the same manner as with client buyers, you have to make manifest to these people the extent of your results. Don’t focus on what you do, focus on what you achieve. It’s far more powerful to say, “I create individual growth and autonomy” than “I coach managers to think for themselves.”

Clients and nonclients alike will “buy” your quality and reputation and be willing to spread them to their circle of friends and colleagues when you follow these simple parameters. You should be striving for these ends in your revenue and referral goals.

You’ll know you are successful when referrals are provided when you request them, that you are very successful when they are virtually all top quality and personally introduced; and that you are extremely successful when they come without prompting, being proactively suggested by your contact.

That’s how you create annuity business. Now, how do you create annuity business that keeps expanding?