SECTION 1

THE DISCIPLINE OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

,

1.1 Project Success or Failure

1.2 Project Management: A Distinct and Changing Discipline

1.3 Project Management Competence

1.4 A Project Management Philosophy

1.5 Benefits of Project Management

1.6 Ethics in Project Management

1.8 Project Management Bodies of Knowledge and PM Certification

1.9 Project Management Process

1.1 PROJECT SUCCESS OR FAILURE

1.1.1 Introduction

It is important to be able to anticipate whether a project will be either a success or a failure. Success or failure is determined by the measures applied for evaluating the project during its life cycle—and when it is complete. Looking ahead and determining those actions that contribute to success or failure can often avoid adverse outcomes.

1.1.2 Success or Failure

1.1.2.1 Success and Failure Are in the Eye of the Beholder. The words “success” and “failure,” like the word “beauty,” are in the eyes of the beholder. In the project management context, the word “success” is used in the context of achieving something desirable, planned, or attempted—that is, the delivery of the project results on time, within budget, and having an operational or strategic fit with the enterprise’s mission, objectives, and goals.

The word “failure” describes the condition or fact of not achieving the expected end results. Project failure is a condition that exists when the project results have not been delivered as was expected. However, if the project results are acceptable to the user, then overrun of costs and schedule may be tolerated.

Determining success or failure requires that performance standards be developed for the project, which can be compared to the results that are being produced. It is important to remember that a key performance factor is whether or not the results of the project can be effectively used by the customer.

Product success or failure may be perceived differently by different project stakeholders:

• A project that has overrun cost and schedule goals but provides the user with the results that had been expected may be judged a success by the user.

• A project team member who gains valuable experience on the project team may consider the project a success.

• A supplier who has provided substantial resources to the project may consider the project a success.

• A contractor who lost a bid to do work for the project may consider the project a failure.

Because of a project’s temporary nature, a determination of relative success or failure may be difficult. The subjective nature of a determination of project success or failure makes it challenging to develop objective measures of performance. The meaning of project success or failure may vary depending on the period in the life cycle when the determination is made.

Nevertheless, there are some general standards that can be used in judging whether a project is a success or a failure.

1.1.3 Project Success—Factors

• The project results have been delivered to the customer, who sees the project as having an appropriate fit with the mission, objectives, and goals of the enterprise.

• The project work packages have been accomplished on time and within budget.

• The overall project results have been accomplished on time and within budget.

• The project stakeholders are happy with the way the project was managed and the results that have been produced.

• The project team members believe that serving on the project team was a valuable experience for them.

• A profit has been realized on the work accomplished on the project.

• The project work has resulted in some technological breakthroughs that promise to give the enterprise a future competitive edge.

• Effective teamwork has been carried out on the project.

• The project has opened up new business improvements or opportunities for the project’s customer.

• Contemporary project management theory and practice have been carried out on the project.

1.1.4 Project Failures—Factors

• The project has overrun cost and schedule goals.

• The project does not have an appropriate fit with the customer’s mission, objectives, and goals.

• The project has failed to meet its technical performance expectations.

• The project was permitted to run beyond the point where its results were needed to support the customer’s expectations.

• Inadequate management processes were carried out on the project.

• A faulty design of the project’s technical performance standards was conducted.

• The project stakeholders were unhappy with the progress on the project and/or the results that were obtained.

• Top management failed to periodically review and support the project.

• Unqualified people served on the project team.

• The project met the initial requirements, but did not solve the longer-range business need.

Given the general standards for determining project success or failure, the contributing factors are shown in Tables 1.1 and 1.2.

Given some of the likely causes of project success or failure, we must recognize that both are end results that can be affected by many forces and factors. These forces and factors are not considered all-inclusive, as each project tends to be unique and there might be additional reasons for success or failure. It is important that the reader recognize that a determination of success or failure is dependent on many matters. Awareness of these factors and forces will improve the chances that the project will be successful and less likely to fail.

TABLE 1.1 Factors Likely to Contribute to Project Failure

• Inadequate status/progress reports |

• Insufficient senior management support and oversight |

• Inadequate competence of project manager regarding understanding of technology; administrative skills; interpersonal skills; communication skills; ability to make decisions; and limited vision—does not see big picture |

• Poor relations with project stakeholders |

• Poor customer relationship |

• Lack of project team participating in the making of decisions |

• Lack of team spirit on project |

• Inadequate resources—both human and material |

• Insufficient planning and control |

• Inadequate engineering change management |

• Unrealistic schedule |

• Underestimated cost, leading to underfunding |

• Unfavorable public opinion |

• Untimely planned project termination |

• Inefficiencies in use of resources |

• Poor definition of authority and responsibility for project team |

• Lack of commitment on the part of team members |

TABLE 1.2 Factors Contributing to Project Success

• Adequate senior management oversight and support |

• Early effective planning |

• Appropriate organizational design for the project |

• Delegated authority and responsibility |

• Efficient system for monitoring, evaluating, and controlling the use of resources on the project |

• Effective contingency planning |

• Strong team member participation in the making and executing decisions on the project |

• Realistic cost and schedule objectives |

• Customer commitment to the project |

• Adequate and continuing customer oversight |

• Project manager’s commitment to established technical performance objectives; budgets; schedules; and use of state-of-the-art management concepts and processes |

• Adequate management information system |

• An effective and efficient management system for the project |

1.1.5 Summary

Some ideas concerning project success and failure were presented that highlight potential areas of concern for the issues of project management. Included in the textual material were some examples of the forces and factors that can contribute to project success or failure. Finally, Tables 1.1 and 1.2 suggest some criteria that may be used to determine the relative success or failure of a project. It is important to consider project success of failure from the viewpoint of the stakeholder, whether that be the senior managers, the project team, the customer, or the public.

1.2 PROJECT MANAGEMENT: A DISTINCT AND CHANGING DISCIPLINE

1.2.1 Introduction

Formal project management has been around for more than 60 years and is practiced in many different industries. The history of project management practices dates back hundreds of years. These processes and practices have been documented and disseminated over the past few decades to contribute to the evolving discipline. A subset of the management discipline is emerging.

1.2.2 Project Management: Profiles of Change

The practices of project management can be traced to antiquity, as evidenced in past major construction projects such as the Great Pyramids, canals, bridges, cathedrals, and other infrastructure projects. Today, project management is an idea whose time has come. A description of the evolution of project management as suggested in the literature follows:

The article “The Project Manager,” published in the Harvard Business Review in May-June 1959, set forth some essential notions about the discipline:

• Projects are organized by tasks requiring an integration across the traditional functional structure of the enterprise.

• Unique authority-responsibility-accountability relationships arise when a project is managed across the traditional elements of the organization.

• A project team is a unique organizational unit dedicated to delivery of project results on time, within budget, and within predetermined technical specifications.

In 1961, Gerald Fish wrote in the Harvard Business Review about the growing obsolescence of the line-staff concept, and described the growing trend in contemporary organizations toward a “functional teamwork” approach to organizational design.

An important contribution to the project management literature appeared in the form of the “matrix” organization, first described by Professor John F. Mee of Indiana University in a 1964 article in Business Horizons. The contributions that this article made included the first description of the nature of the evolving “matrix” organization to include the “web of relationships” that replaced the line and staff relationship of work performance.

1.2.2.1 Role of Senior Management in Projects. In 1968, a landmark study of the practices of senior management in leading industrial corporations noted the responsibilities of senior managers for projects. The study noted high-level committees (such as the board of directors) were widely used as a valuable organizational design to:

• Establish broad policies.

• Coordinate line and technical management.

• Render collective judgments on the evaluation of corporate undertakings.

• Conduct periodic reviews and monitoring of ongoing programs and projects.

1.2.3 The Emergence of Project Management

Distinctive factors that stand out in the emergence of project management, include:

• Demonstration of effectiveness through such noteworthy initiatives as the Manhattan Project and the Polaris Submarine Project.

• Development of specialized techniques for scheduling project activities such as PERT, CPM, and cost-schedule control systems.

• An early definition of a project as “any undertaking that has definite, final objectives representing specified values to be used in the satisfaction of some need or desire.” (Ralph Currier Davis, The Fundamentals of Top Management, Harper and Brothers, New York, 1951, p. 268.)

• The emergence of concepts which support the growing field of project management to include:

• A distinct life cycle

• Cost considerations

• Schedule factors

• A technical performance capability

• An assessment of the operational or strategic fit of the project results into the project owner’s organization.

Some of the unique characteristics of project management coming forth in its evolution include:

• Projects are ad hoc endeavors that have a defined life cycle.

• Projects are building blocks in the design and execution of organizational strategies.

• Projects are the leading edge of new and improved organizational products, services, and organizational processes.

• Projects provide a philosophy and strategy for the management of change in the organization.

• The management of projects entails the crossing of functional and organizational boundaries.

• The management of a project requires that an inter-functional and interorganizational focal point be established in the organization.

• The traditional management functions of planning, organizing, motivation, directing, and control are carried out in the management of projects.

• Both leadership and managerial capabilities are required for the successful completion of a project.

• The principal outcomes of a project are the accomplishment of technical performance, cost, and schedule objectives.

Projects are terminated upon successful completion of the cost, schedule, and technical performance objectives—or earlier in their life cycle when the project results no longer promise to have an operational or strategic fit in the organization’s future.

1.2.3.1 Authority-Responsibility. In 1967, Cleland, writing in Business Horizons magazine, described the difference between de facto (earned) authority, and de jure (legal) authority.

De jure, or legal authority, comes from the organizational position that an individual holds and is reflected in project documentation such as a letter of appointment, position descriptions, policy documents, and related documentation.

De facto authority is that which comes from the individual’s knowledge, expertise, interpersonal skills, experience, and demonstrated experience to work with people.

1.2.3.2 A Project Management System. In 1977, Cleland published a short article in the Project Management Quarterly which described a project management system (PMS). This system is described in Sec. 7 of this Handbook.

1.2.4 Contribution of Project Management

Project management during its evolution contributed to a theory and practice in its own right as it matured as a discipline. A summary of the major changes that have come about in project management since its emergence includes:

• Recognition that project management is a discipline in its own right, as a branch of knowledge and skills

• Discovery and establishment of the legitimacy of the “matrix” organizational design as a means for delegating authority, responsibility, and accountability for the management of project resources

• Stimulated and propagated the growth of professional associations in the field

• Developed and disseminated the concept of a PMS as a performance standard for the management of project resources

• Provided the “strategic pathway” for the emergence and use of alternative teams in the operational and strategic management of the organization

• Became the principal means for the management of ad hoc activities in organizations

• Tested and established the legitimacy of the “horizontal dimension” in contemporary organizations

• Defined the concept of the influence of project stakeholders, and the importance of being able to manage project stakeholders

• Created and defined a new career path for managers and professionals

1.2.5 A Contemporary Model of Project Management

An article in Fortune magazine captured the essence of today’s state of project management. The key messages of this article are shown in Table 1.3.

TABLE 1.3 Key Messages Regarding Project Management

• Mid-level management positions are being cut. |

• Project managers are a new class of managers to fill the niche formerly held by middle managers. |

• Project management is the wave of the future. |

• Project management is expanding out of its traditional uses. |

• Managing projects is managing change. |

• Expertise in project management is a source of power for middle managers. |

• Personal job security is elusive in projects, as each project has a beginning and an end. |

• Project leadership is what project managers do. |

Source: Thomas H. Stewart, “The Corporate Jungle Spawns a New Species,” Fortune, July 10, 1995, pp. 179–180. |

1.2.6 Summary

A brief summary of some key characteristics of the evolution of project management was presented in this section. These key characteristics define project management today and set the mark for continual improvements to the process.

The origins of project management appeared in antiquity, and are represented in the artifacts from historical periods. Today project management is viewed as an idea whose time has come. The continued evolution of project management has created a distinct philosophy reflected in management literature of the discipline.

1.3 PROJECT MANAGEMENT COMPETENCE

1.3.1 Introduction

Project management competence is essential for organizations’ projects as building blocks to their future growth and profitability. In the past, knowledge was considered the key to success, but the concept of individual competence within project management is recognized as a more powerful approach to business.

Webster’s II New College Dictionary defines competence as being properly qualified and capable, adequate for the stipulated purpose. Roget’s International Thesaurus offers many synonyms for competence, such as ability, ableness, enablement, capability, capableness, capacity, efficiency, efficacy, sufficiency, adequacy, “the stuff,” and so forth.

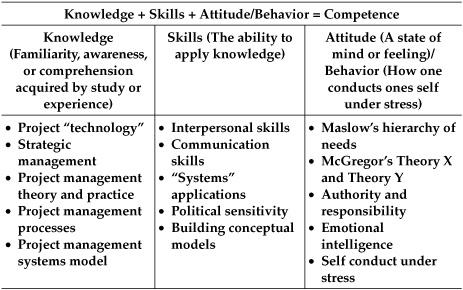

Competence depends on the personal characteristics of an individual, reflected in his or her knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Knowledge consists of suitable familiarity, awareness, and comprehension acquired by study and experience. Skill is the ability to apply knowledge and attitude is a state of mind or feeling.

Foundations of Competence

![]()

1.3.2 Knowledge

The project manager must possess several basic elements of knowledge:

• An understanding of the technology of the project. A project is usually carried out within the context of a relevant technology. These technologies vary widely. For example, the technologies involved in a highway construction project will be different than those involved in a concurrent engineering project, or a project to develop an information system for an organization.

• A general understanding of the concept and process of strategic management as applied to the organization involved. Strategic management deals with the development of future initiatives for the organization as if that future mattered. It is particularly important that the project managers understand how their project is a building block in the design and execution of organizational strategies of the organization.

• A solid understanding of the theory, process, and practice of project management in the management of ad hoc initiatives supporting organizational purposes. In particular, the competent project manager should understand how the management of projects differs from the management of traditional work or activity within that organization.

• An understanding of and familiarity with the management processes involved in the management of a project. These processes, usually defined in the context of project planning, organizing, motivation, direction, and control, constitute the framework from which a project is managed within the context of the project stakeholders.

• A conceptual and working understanding of the relevance of a PMS to the management of a project. A PMS consists of the following subsystems:

a. A facilitative organizational subsystem (FOS) is the organizational arrangement that is used to superimpose the project teams on the functional structure of the enterprise. The resulting matrix portrays the formal authority and responsibility patterns and reporting relationships of members of the project team. Two complementary organizational units tend to emerge in such an organizational context: the project team and the functional units.

b. The project planning subsystem (PPS), which starts with the development of a work breakdown structure (WBS). Under the project planning activity the objectives, goals, and strategies are prepared. The project cost, schedule, and technical performance parameters are defined, along with strategies on what project resources are required and how these resources will be managed during the life of the project.

c. The project management information subsystem (PMIS) contains the information required to manage the project. The PMIS plays a key role in the monitoring, evaluation, and control of the resources used on the project. The PMIS may be formal or informal and is needed to determine the status of the project and how effectively the project resources are being utilized, and to gain an understanding of how soon—and how well—the project will be completed.

d. The project control subsystem (PCS) provides for the selection of performance standards for the project technical performance specifications, schedules, and cost objectives. This subsystem is used to compare actual progress with planned progress, with guidance on what might be required to get the project back on the correct trajectory. The rational for a control subsystem arises out of the need to monitor the various organizations that are performing work on the project. The PCS and the PMIS work together to provide the intelligence to determine project status and how likely the project results will be to contribute to the goals and objectives of the organization.

e. The cultural ambience subsystem (CAS) portrays how the project is carried out within the human and social context of the enterprise. The emotional patterns of the social groups, their perceptions, attitudes, prejudices, assumptions, experiences, and values, all go to develop the organization’s cultural ambience for project management. This ambience influences how people act and react, how they think and feel, and what they say in the organizations, all of which ultimately determines what is taken for socially acceptable behavior in the organization.

f. The human subsystem (HS) involves just about everything associated with human element. An understanding of the human subsystem requires some knowledge of sociology, psychology, anthropology, communications, philosophy, leadership, and so on. Motivation is an important consideration in the management of the project team. Project managers must find ways of putting themselves into the context of human subsystem of the project so that the project team members trust and are loyal in supporting project purposes. The artful management style that project managers develop and encourage within the project team may well determine the success or failure of the project.

1.3.3 Skill

Skill is the proficiency, ability, or dexterity required to carry out responsibilities required for a profession and the performance of a role in a social setting. An individual performing a project management role requires a unique combination of skills to effectively function in a project environment. These skills include:

• Interpersonal skills—the ability to work through people in the accomplishment of the project goals and objectives. They involve the ability to understand people, to empathize with them, to provide them with rewards for their work, and to have them believe and trust your major considerations in working successfully with people. Lack of interpersonal skills is recognized as one of the major causes of project failures in organizations.

• Communication skills—the ability to effectively transmit information between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior. Peter Drucker, probably the best-known author in the field of management, believes that the ability to communicate heads the list of criteria for success. He also believes that one’s effectiveness depends on the ability to reach others through the spoken or written word when working in organizations. This ability to communicate is perhaps the most important of all the skills an individual can possess.

• Ability to sense and see the “systems” applications of the work that the project manager and the project team members do is an important skill. This means that one who sees the system’s application perceives the larger context in which the project exists. Such a larger context would place the project itself as a building block in the strategic management of the enterprise. Also, in the management of the project, consideration would be given to the multiple stakeholders who have—or believe that they have—a stake or claim in the management of the project and in the results that the project produces.

• Political sensitivity is an important skill for the project manager to have. Political issues are likely to emerge during the conceptual phase of the project as well as during the production (construction) of the project results. Then, when the project user employs the results of the project into the operational or strategic elements of the organization, additional political considerations will emerge. Politics matter—an effective project manager knows the politics, particularly in the management of the project stakeholders. The effective management of stakeholders, taking into consideration their needs, can spell the difference between success or failure of the project.

• Management style is the manner or mode in which the project manager, as well as other managers and individuals, carry out their responsibilities. How people conduct themselves is often a reflection of their knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A project manager who maintains an interest in the well-being of the team members and who can clearly communicate with these people will likely have a successful project. Sensitivity to the effects of decisions on everyone involved, being a good listener, and treating team members as human beings, rather than just individuals who happen to be working on the project, are important management style considerations.

• Building conceptual models of the project and the manner in which it should be managed is an important skill. Models serve as conceptual performance guides that can guide the making and execution of decisions in the allocation of resources on the project. A conceptual model for the organizational design of the project, how the project will be planned, the management style to be followed, how the project results will be monitored, evaluated, and controlled, are all places where conceptual models play a role in guiding the thinking and action of the project team members.

1.3.4 Attitude and Behavior

Attitude—a state of mind or feeling about the project and how it is to be managed—is an important component of one’s ability. The point of view, the position, and the opinion held and expressed by the people on the project will influence their behavior in working with the team members. The attitude that a person holds will influence how that person manages the project team. How a manager—or a professional—comes across during the many face-to-face relationships will influence how that person is perceived. Attitude plays an important role in working with and through people.

Behavior is how one conducts oneself and exercises self-control under periods of stress. Whether one is in a leadership role or a contributing role, appropriate behavior is needed to support the projects. Some behaviors that support project work are:

• Appropriately delegates authority and responsibility

• Assumes full responsibility for one’s actions

• Consults with the project team on decisions

• Serves as a role model for other team members

• Maintains a high frustration threshold

• Communicates with others—up, down, horizontally

• Responses to emotional questions and issues in a nonemotional manner

• Uses humor to defuse tense situations

• Shares credit with others for successes; takes responsibility for failures

Douglas McGregor’s concept of Theory Y and Theory X within an individual’s needs has considerable merit. Theory X sees people as having an inherent dislike of work and avoiding it when possible. Because of this, characteristic people have to be controlled, directed, and threatened with punishment to get them to do their best work. In contrast, Theory Y states that physical and mental effort in work is as natural as play or rest. The average individual learns under proper conditions to seek responsibilities. Theory Y places the responsibility for motivation and attitudes of people squarely on the manager.

A. H. Maslow put forth the idea of a “hierarchy of needs,” which places the various needs of individual in relationship to one another. He believes that an individual has five basic levels of needs:

• Sustaining the body, such as by satisfaction of hunger, thirst, and sleep

• Adequate protection to ensure safe and secure lives

• Satisfactory associations with other people

• Esteem: self-respect and the respect and approval of others

• The opportunity to achieve one’s potential for maximum self-development, leading to personal success

Maslow believes that the needs of an individual can only be attained if the lower level of needs has first been satisfied.

1.3.5 Authority and Responsibility

The prudent and caring project manager should be aware of these needs and, as far as possible, contribute to the cultural ambience of the organization to facilitate the attainment of these needs. How the project managers and other individuals perceive their role and responsibility in the management of the project is important. Authority consists of the authority that is granted to the organizational position that the individual occupies, and the influence that an individual exercises because of his or her knowledge, skills, and attitudes. What this means is that one cannot depend on just the delegated grant of authority, but must develop the personal attributes that can be used to influence people working on the project. This is particularly important when dealing with the project stakeholders, many of whom are not under the delegated authority from the organization.

1.3.6 Emotional Intelligence

The notion of emotional intelligence (EI) is explained in a book by Daniel Goleman of that title. EI has its roots in the idea of social intelligence, proposed by E. L. Thorndike in 1920. He defined social intelligence as “the ability to understand and manage men and women, boys and girls—to act wisely in human relations.”

Goleman states that “Emotional intelligence comprises the skills that help people harmonize, and should become increasingly valued as a workplace asset in the years to come.” Emotional intelligence provides extraordinary insight into the development and use of interpersonal skills in a social setting, such as in the project management environment that managers and professionals face every day. These individuals will be well rewarded in developing an understanding of EI and applying it in the social setting of project management.

1.3.7 Individual Competence

Competence is expressed in many ways within an organization, and different levels of positions within an organization may apply different definitions. An individual competence model is one way of promoting understanding and appreciation for top performers.

Individual Competence Model

The collective sum of individual competence has a significant influence on the capability of an organization to perform and grow at a competitive pace.

1.3.8 Summary

Project management competence includes all of the understanding and insight developed over the last several decades in the research and practice of the human subsystem in organizations. As the reader ponders the basic thoughts expressed in this topic area of project management, he or she should gain an awareness of the extraordinary role that people play in the management of projects as well as some of the important considerations to be followed in the management of people.

Project managers should be aware of, and live by, the basic equation:

Knowledge + Skills + Attitude/Behavior = Competence

1.4 A PROJECT MANAGEMENT PHILOSOPHY

1.4.1 A Project Management Philosophy

This book is about project management, a field of practice and study that has evolved since antiquity. In the last 60 years, there has been a dramatic increase in both book and periodical literature, and this Handbook presents the key elements to be found in this discipline. In this section, a philosophy of project management will be presented as an overview of this important discipline, and as a basing point from which people who work in project management can use to gain a conceptual understanding of the major elements of this discipline. Figure 1.1 presents an overview of the major considerations involved in the management of a project. These considerations are covered in this Project Manager’s Portable Handbook, along with many other issues with which the project team should be conversant.

FIGURE 1.1 Major considerations—project management.

1.4.2 A Philosophy

A philosophy is an outlook about something, such as a field of thought and practice. Other meanings of this word include a “way of thinking” about the field, such as an inquiry into the nature of project management to include its conceptual framework, processes, techniques, and framework of principles. Those who are involved in project management will find that the development of a philosophy or way of thinking about this discipline is valuable.

A philosophy is a way of thinking. |

1.4.3 The Conceptual Framework of Project Management

A project consists of a combination of organizational resources pulled together to create something that did not previously exist, and that will provide an enhanced performance capability in the design and execution of organizational strategies. Other characteristics of a project include:

• Projects are the principal means by which an organization deals with change.

• Changes in organizational products, services, or organizational processes are brought about through the use of projects.

• Each project has specific objectives regarding its cost, schedule, and technical performance capability.

• Each project, when completed, should add to the operational and/or strategic capability of the organization.

• Projects have a distinct life cycle, starting with the emergence of an idea, through to the delivery of the project results to a user or “customer.”

• Projects change the organizational design and culture of an organization, primarily through the workings of the “matrix organization.”

• A focal point is designated in the organization through which the resources supporting a project are planned, integrated, and utilized to deliver the project results.

• Specialized planning, organization, motivation, leadership, and control techniques have emerged to support the management of a project’s resources.

• Today, project management is recognized as having a rightful place in the continued emergence of the management discipline.

• Although project management emerged in the construction industry, today it is practiced in all industries, in military entities, educational entities, ecclesiastical organizations, in the social field, and in the political domain.

• The management of the project stakeholders poses a major challenge for the project team.

• A body of knowledge has developed to describe the art and science of project management.

• This body of knowledge is changing the way that contemporary organizations are managed.

• Project management is the wave of the future—the role played by project management in the years ahead will be challenging, exciting, and crucial.

1.4.4 The Project Management Functions

Project management is carried out through a management process consisting of the core functions of management to utilize resources to accomplish project ends. These core functions are shown in Fig. 1.2 and are briefly discussed below.

Planning—development of the objectives, goals, and strategies to provide for the commitment of resources to support the project.

Organizing—identification of the human and non-human resources required, providing a suitable layout for these resources, and the establishment of individual and collective roles of the members of the project team, who serve as a focal point for the use of resources to support the project.

FIGURE 1.2 The core functions of project management.

Motivating—the process of establishing a cultural system that brings out the best of people in their project work.

Directing—providing the leadership competence necessary to ensure the making and execution of decisions involving the project.

Control—monitoring, evaluating, and controlling the use of resources on the project consistent with project and organizational plans.

Summary material will be presented on two of the core functions of project management. Elsewhere in this book additional information will be provided on these functions as well as on the three additional functions, namely, motivation, direction, and control.

1.4.5 The Essential Work Package Elements of Project Planning

Project planning is the process of thinking through, and making explicit, the objectives, goals, and strategies necessary to bring the project through its life cycle. The work packages involved in project planning include:

• Establish the strategic fit of the project. Ensure that the project is truly a building block in the design and execution of organizational strategies, and that it provides the project owner with an operational capability not currently existing or improves an existing capability.

• Identify strategic issues likely to affect the project.

• Develop the project technical performance objective. Describe the project deliverable end product(s) that satisfies a customer’s needs in terms of capability, capacity, quality, quantity, reliability, efficiency, and so forth.

• Describe the project through the development of the project work breakdown structure (WBS). Develop a product-oriented family tree division of hardware, software, services, and other tasks to organize, define, and graphically display the product to be produced, as well as the work to be accomplished to achieve the specified product.

• Identify and make provisions for the assignment of the functional work packages. Decide which work packages will be done in-house, obtain the commitment of the responsible functional work managers, and plan for the allocation of appropriate funds through the organizational work authorization system.

• Identify project work packages that will be sub-contracted. Develop procurement specifications and other desired contractual terms for the delivery of the goods and services to be provided by outside vendors.

• Develop the master and work package schedules. Use the appropriate scheduling techniques to determine the time dimensions of the project through a collaborative effort of the project team.

• Develop the logic networks and relationships of the project work packages. Determine how the project parts can fit together in a logical relationship.

• Identify the strategic issues that the project is likely to face. Develop a strategy for how to deal with these issues.

• Estimate the project costs. Determine what it will cost to design, develop, and manufacture (construct) the project, including an assessment of the probability of staying within the estimated costs.

• Perform risk analysis. Establish the degree or probability of suffering a setback in the project’s schedule, cost, or technical performance parameters.

• Develop the project budgets, funding plans, and other resource plans. Establish how the project funds should be utilized, and develop the necessary information to monitor and control the use of funds on the project.

• Ensure the development of organizational cost accounting system interfaces. Because the project management information system is tied in closely with cost accounting, establish the appropriate interfaces with that function.

• Select the organizational design. Provide the basis for getting the project team organized, including delineation of authority, responsibility, and accountability. At a minimum, establish the legal authority of the organizational board of directors, senior management, and project and functional managers, as well as the work package managers and project professionals. Use the linear responsibility chart (LRC) to determine individual and collective roles on the project team.

• Provide for the project management information system. An information system is essential to monitor, evaluate, and control the use of resources on the project. Accordingly, develop such a system as part of the project plan.

• Assess the organizational cultural ambience. Project management works best where a supportive culture exists. Project documentation, management style, training, and attitudes all work together to make up the culture in which project management is found. Determine what project management training would be required. What cultural fine-tuning is required?

• Develop project control concepts, processes, and techniques. How will the project’s status be judged through a review process? On what basis? How often? By whom? How? Ask and answer these questions prospectively during the planning phase.

• Develop the project team. Establish a strategy for creating and maintaining effective project team operations.

• Integrate contemporaneous state-of-the-art project management philosophies, concepts, and techniques. The art and science of project management continues to evolve. Take care to keep project management approaches up-to-date.

• Design project administration policies, procedures, and methodologies. Administrative considerations often are overlooked. Take care of them during early project planning, and do not leave them to chance.

• Plan for the nature and timing of the project audits. Determine the type of audit best suited to get an independent evaluation of where the project stands at critical junctures.

• Determine who the project stakeholders are and plan for the management of these stakeholders. Think through how these stakeholders might change through the life cycle of the project.

1.4.6 Organizing for Project Management

Project organizing deals with the determination of the individual and collective roles that people in the organization play in supporting project objectives, goals, and strategies. The major considerations involved in such organizing include:

• The project-driven matrix organization has a distinct structure, which at first glimpse appears to violate traditional organization principles.

• The matrix organizational design is a blend of the project and functional organizational units in which there is a sharing of authority responsibility, and accountability.

• The functional managers and the project managers in the enterprise carry out complementary roles with regards to the project.

In its most elementary form, the interface between the project effort and the functional effort constitutes the key of the matrix organization carried out through the project work packages.

Extraordinary authority-responsibility-accountability relationships exist in the matrix organization.

A linear responsibility chart (LRC) can be used to establish the authority and responsibility relationships involved in the individual and collective roles with the organization.

Authority is defined as the legal right to act; responsibility is the obligation to act. The ambiguities of the matrix organization provide ample opportunity for the ability of the project manager to exercise legal authority as well as the influence that arises from that individual’s competence.

Care must be taken to prescribe the legal authority that the manager, and the members of the project team have.

In the final matters of managing the project, the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the project manager will be the principal determinant in the success or failure of the project.

1.4.7 Summary

This section presented the idea of a project management philosophy as a way of thinking about the conceptual framework, processes, techniques, and principles that are involved in the management of projects. A philosophy was described as a way of thinking about the management of projects. Two figures were presented which identified the major considerations and the use of key management functions in the project management process.

1.5 BENEFITS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1.5.1 Introduction

Project management is a profession that bridges many industries and is a process that delivers unique benefits. Project management is a discipline that has significant advantages over other processes as well as being adaptable to fit the unique needs of different industries. Project management can be tailored to fit many different situations around the world and can be designed to accommodate various levels of sophistication.

Project management is the principal change agent. |

1.5.2 Background

Organizations and people gain significantly from improved processes that provide the optimum solution to business requirements. Project management has the potential, when fully implemented, to provide the most effective means of developing and delivering new product services and organizational processes. The project management process is a streamlined process to focus specifically on the end result and delivery to customers.

The process of project management as a means of dealing with organizational change is successfully used in many industries today. The number of different applications of the process in the management of change is also expanding. The basic concepts and processes of project management permit flexibility to meet the needs for an effective change strategy that realizes the most benefits.

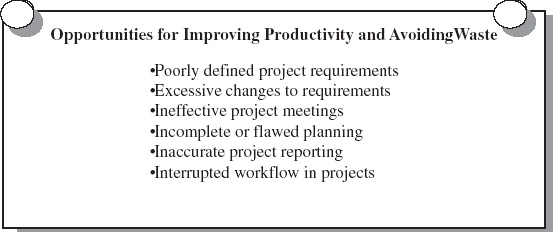

Benefits are derived from processes when there is a minimum use of resources and maximum stakeholder satisfaction. Waste in any area is a negative benefit, or an opportunity, for a project to improve. Waste is defined as “any consumption of resources (materials, people’s time, energy, talent, and money) in excess of the amount required to do the job.”

Some of the most frequent opportunities for improving productivity and avoiding waste are shown in Fig. 1.3.

1.5.3 Project Management and Benefits

The number of benefits realized is directly related to the effectiveness of the implementation of project management. Well-developed project management processes that are tailored to the organization provide the most benefits. These processes must also be closely followed to ensure the practices align with the intended outcomes.

An example of following the project management process is in the area of planning. Planning the project is critical to successfully defining the path to project completion and product delivery. Weak or flawed planning will allow the project to drift off course and waste effort. Positive benefits of improved productivity and effectiveness are derived when the planning is adequate to guide the project team to the completion of all project work.

FIGURE 1.3 Opportunities for improving productivity and avoiding waste.

1.5.4 Benefits of Project Management

Benefits of project management encompass several areas. Identifying the different groups of stakeholders in projects is helpful in determining the type of benefit derived by each. These benefits are best listed as improvements or enhancements to the group. The most likely stakeholders are:

• The organization as a business, either for-profit or not-for-profit

• Senior management of the organization, which includes the manager of project managers, to the president of the organization, and through to the board of directors for major projects

• Project leaders and project team members, or those working the project

• Customers of projects, the consumer, user, owner, and financier

Benefits that are derived from project management as compared to other methods are listed below. Benefits are generally considered within the different groups in Fig. 1.4.

1.5.5 Benefits to the Organization

• Improved productivity through providing the most direct path to the solution of a problem

• Improved profits through reducing wasted time and energy on the wrong solutions

FIGURE 1.4 Project management certification benefits.

• Improved employee morale through greater job satisfaction

• Improved competitive position within industry through bringing faster results to situations

• Improved project process and workflow definition

• Improved capability and maturity in business solutions

• More success and fewer failures through the dedicated focus on work

• Better decision making on continuation/termination of work efforts

• Improved reward system for senior managers, project leaders, and project team members

• Smoother integration of project results into the organization

• Improved product, service, or organizational process development and implementation

1.5.5.1 Benefits for Senior Managers

• Confidence in outcomes for work efforts through better predictability

• Reduced number of changes to work effort during execution

• Faster delivery of products and services that meet customer requirements

• Better information for leadership decision making

• Improved communications with stakeholders

• Confidence in the organization’s business capability

• Improved approval process for new work initiation through better requirement definition

• Better facilitation of organization mission, objectives, and goals

1.5.5.2 Benefits for Project Leaders and Team Members

• Improved job satisfaction through better performance

• Reduced hassle from changing requirements

• Pride in workmanship

• Confidence in ability to manage/work toward solution

• Less effort (hours worked) with better results

• Improved communications with senior managers and customers

• Confidence in ability to complete the work

• Better work tracking and control through better information

• Improved professional competence development

1.5.5.3 Benefits for Customers

• Confidence in senior management, project leader, and project team

• Confidence in delivery of required product and services

• Confidence in delivery on time within price

• Improved visibility into work planning and execution process

• Improved satisfaction with the product or service

• Improved product definition and communication of own requirements

• Improved working relationship with the project team

Benefits derived from project management are typically viewed as a difference between what is provided under current planning and execution practices and what will be done in the future. In the project environment, benefits are most often viewed as:

• Technical—the result of the project’s product or service

• Customer satisfaction—the customer’s feeling as to the value of the end product, service, and other factors

• Delivery time—meeting the date when the product or service is needed

• Price/cost—the price or cost has not exceeded the value delivered

The change between the level of benefits delivered before and after new project management practices must be measured to have a quantifiable meaning. Without solid project plans, it is often difficult to measure the quantitative advances objectively. Unfortunately, too many measures of effectiveness are developed and implemented from a subjective basis.

1.5.6 Measures of Success

Measures of success are used for two primary purposes. First, a measure of success tells the project team when the work is complete. Second, if the work cannot be completed, it establishes a means for measuring the degree of success in meeting the requirements.

Measures of success permit gauging progress as well as identifying a benchmark for subsequent improvement efforts. Starting a task or group of tasks in a project should begin with the desired outcome or desired results. This can be communicated to the performing party and sets expectations for the completed work.

Incomplete work, or failure to meet the desired measure of success, establishes a point from which improvements can be made. When a task or group of tasks fail to meet the agreed upon measure of success, it is from this point that an evaluation can be made for future improvements. Future improvements may result from process improvement or training of the workforce or both.

Setting measures of success should stretch the capability of the project team. The stretch measure of success will often provide better results with a failure than an easy goal. Additional benefits will be derived from stretch measures of success. Project teams given stretch goals must be informed that goals may not be attainable, but their efforts will provide the best results, although the progress may be less than goals.

1.5.7 Summary

Project management processes have the capability to bring numerous benefits to an organization and the people working on the projects. The list of benefits derived from using proven project management methodology, techniques, standards, tools, and practices have been identified within categories as to who is the beneficiary. Each category may have a different perception of the benefits derived from project management based on their organizational position.

Benefits derived from improved processes include more confidence in the outcome of the project, less stress on the performing project team, higher productivity rates, less waste of valuable resources, reduced costs for projects, and faster time to market. The intangible benefits include an improved organization image as a company with a core competence in project management. An organization may derive other benefits from using the best practices of project management and may significantly improve their relative competitive position in the industry.

1.6 ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1.6.1 Introduction

Ethics in project management encompasses many areas of personal and professional conduct because of the range of project locations. Project personnel are required to work in different countries that have unique cultural aspects and different value systems. In some countries, bribes, a conflict in the U.S. environment, are expected and often demanded to ensure continuity of work on a project.

Ethics in all environments are not universally understood or agreed upon. Ethics can often be situational and loosely applied or they can be rigorous and demanding on project personnel. The lack of a code of ethics or training in ethics can also affect how personnel respond to challenging situations. Random or unequal application of a code of ethics can also affect practiced ethics.

A code of ethics is required for all recognized professionals. It is expected that professionals will freely state their values and live to those statements of ethical conduct. The code of ethics for a professional group must be advertised and enforced to be effective.

Practiced ethics do not ensure project success, but the lack of ethics leads to project failure. |

1.6.2 Ethical Obligations of a Professional

To be considered professional, individuals must clearly state their code of ethics by which they can be expected to abide. The code of ethics must consider the legitimate needs of others as well as identifying all obligations that the professional assumes. This code of ethics sets the expectation of those being served and clearly states the obligations.

Project managers may have a code of conduct within their organization to guide them in the manner in which they work with others. The best known code of conduct for project managers is the Project Management Professional Code of Ethics. This code was developed in 1983 by the Project Management Institute (PMI®) as a part of its Project Management Professional (PMP®) Certification Program. Individuals being certified to be a Project Management Professional must subscribe to and support the PMP Code of Ethics.

When a code of ethics is not adopted by an individual or a group of individuals, the bounds of ethical conduct are not defined. Individuals will vary in the practice and enforcement of ethical conduct to the extent that there is no consistent practice. Random and situational ethics do not support professionalism or build confidence in others that the collective group can or will abide by any rules of conduct.

1.6.3 Code of Ethics

The original code of ethics of PMI for project managers is provided as a model for all professional project management practitioners to follow.

1.6.3.1 Code of Ethics for the Project Manager. Preamble: Project Managers, in the pursuit of the profession, affect the quality of life for all people in our society. Therefore, it is vital that Project Managers conduct their work in an ethical manner to earn and maintain the confidence of team members, colleagues, employees, employers, clients and the public.

Article I: Project Managers shall maintain high standards of personal and professional conduct and:

A: Accept responsibility for their actions.

B: Undertake projects and accept responsibility only if qualified by training or experience, or after full disclosure to their employers or clients of pertinent qualifications.

C: Maintain their professional skills at the state of art and recognize the importance of continued personal development and education.

D: Advance the integrity and prestige of the profession by practicing in a dignified manner.

E: Support this code and encourage colleagues and co-workers to act in accordance with this code.

F: Support the professional society by actively participating and encouraging colleagues and co-workers to participate.

G: Obey the laws of the country in which work is being performed.

Article II: Project Managers shall, in their work:

A: Provide necessary project leadership to promote maximum productivity while striving to minimize cost.

B: Apply state of the art project management tools and techniques to ensure quality, cost and time objectives, as set forth in the project plan, are met.

C: Treat fairly all project team members, colleagues and co-workers, regardless of race, religion, sex, age or national origin.

D: Protect project team members from physical and mental harm.

E: Provide suitable working conditions and opportunities for project team members.

F: Seek, accept and offer honest criticism of work, and properly credit the contribution of others.

G: Assist project team members, colleagues and co-workers in their professional development.

Article III: Project Managers shall, in their relations with their employers and clients:

A: Act as faithful agents or trustees for their employers and clients in professional or business matters.

B: Keep information on the business affairs or technical processes of an employer or client in confidence while employed, and later, until such information is properly released.

C: Inform their employers, clients, professional societies or public agencies of which they are members or to which they may make any presentations, of any circumstance that could lead to a conflict of interest.

D: Neither give nor accept, directly or indirectly, any gift, payment or service of more than nominal value to or from those having business relationships with their employers or clients.

E: Be honest and realistic in reporting project quality, cost and time.

Article IV: Project Managers shall, in fulfilling their responsibilities to the community:

A: Protect the safety, health and welfare of the public and speak out against abuses in these areas affecting the public interest.

B: Seek to extend public knowledge and appreciation of the project management profession and its achievements.

1.6.4 Ethics for the Project Management Practitioner

The above code of ethics is an example and was derived from an extensive study of ethics. The study addressed all the areas of ethical obligations that engineers must exhibit to be professionals. For project management professionals, the obligations are depicted in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 shows a general approach to whom there is an owed ethical obligation. If a person is a project manager, for example, there is a greater obligation to the team members than if the project manager is a team member. The greater the responsibility within projects, the greater the ethical obligation to serve those in subordinate positions.

The greater the professional responsibility, the greater the ethical obligation. Project managers must demonstrate ethical behavior to team members. |

Honesty and integrity are essential elements of any profession. Honesty and integrity are the foundation for trust and confidence in the professional. Individuals deviating from the truth and fabricating progress results on a project will soon have both team members and superiors questioning their ability to effectively manage a project.

Willingness to accept responsibility and be held accountable for one’s actions is another key element of ethical behavior. A project manager is responsible for all the activities that occur or fail to occur on a project. It is unethical and unfair to place the blame on others when the project manager is clearly at fault.

TABLE 1.4 Obligations of Project Management Professionals to Others

• Society in general or the public’s interest |

• Clients or customers of project work |

• Employers of the project management professional |

• Employees working for the project management professional |

• Project team members |

• Professional colleagues in project management and related fields |

1.6.5 Enforcement of the Code of Ethics

A code of ethics is only effective for professionals when the professional abides by all aspects of the obligation. Deviations from the code of ethics must be enforced to ensure credibility of the profession. A system is required to investigate reported abuses and implement corrective actions.

A self-correcting system for abuses is best. However, the violator of the code of ethics will typically deny any wrongdoing. When violations are reported, it is necessary for the professional group to conduct a fair and impartial investigation to determine the facts. The facts must be reviewed and a finding of a violation or no violation must be made. The finding is then referred to a body authorized to either dismiss the allegation or initiate some form of punishment.

Punishment for violations of a code of ethics may range from an oral or written warning if the offense is minor to removal of credentials if the person has committed a serious breach of ethics. Because professional groups only have authority over the code of ethics in a voluntary agreement with the individual, punishment can only encompass removing what the professional group may grant. Where the violation of the code of ethics is also a violation of law, the individual may be punished under the law by the body having jurisdiction.

Punishment for violations of the code of ethics is a harsh and disruptive process. It is best to avoid violations of the code of ethics through an active program of education and reinforcement of the need to abide by these rules. When an erosion of the code of ethics occurs through small deviations, the corrective measures must be enforced to prevent further degradation.

1.6.6 Summary

Ethical behavior for all true project management practitioners is guided by a code of ethics. If the code of ethics is missing, then there is no consistent professional obligation to others and the individual cannot be considered a professional.

Codes of ethics identify obligations to different parties. These obligations are formally documented and made available to others as a means of establishing the expectations of others. These expectations, like a contract, provide a basis for the professional’s conduct and the expected outcomes from the professional.

The extent to which a professional follows the code of ethics determines the confidence level that the other party assigns. Individuals operating on the boundaries of ethical conduct will find an erosion of confidence in their professional competence. Honesty and integrity are fundamental to building and maintaining this confidence as a professional.

1.7 PROJECT LIFE CYCLE

1.7.1 Introduction

New products, services, and organizational processes have their genesis in ideas evolving with the enterprise. Typically such ideas go through a distinct life cycle—a natural and pervasive order of thought and action. In each phase of this life cycle different levels of thought and activities are required within the enterprise to assess the value of the emerging idea as it evolves during its life cycle. The representative phases of a life cycle usually include those phases depicted in Fig. 1.5.

The life cycle of a project can last from just a few weeks or months to 10 or more years, such as in the pharmaceutical industry, or a major construction project such as the Channel Tunnel. These phases, and an analysis of what such phases will do for the project, are discussed below.

1.7.2 The Conceptual Phase

During this phase the environment is examined, forecasts are prepared, objectives and alternatives are evaluated, and the initial examination of the technical performance, cost and schedule aspects of the idea’s development are examined. Other activities undertaken during the conceptual phase are cited in Table 1.5.

There should be a high mortality rate of potential projects during the conceptual phases. Rightly so, as it is during this phase that sufficient study should be carried out about the project’s expectations that a decision can be made regarding the potential usefulness and survivability of the project.

1.7.3 The Definition Phase

The purpose of the definition phase is to determine the cost, schedule, technical performance expectations, resource requirements, and likely operational and strategic fit of the probable project results. Issues to be resolved during the definition phase include these listed in Table 1.6.

FIGURE 1.5 Generic model of project life cycle.

TABLE 1.5 Conceptual Phase Activities

• Initial assessment of the resources required. |

• Development of preliminary insight into the operational or strategic value of the project in complementing existing enterprise purposes. |

• Determination if the expected project results are needed. |

• Establishment of preliminary objectives and goals for the project. |

• Organization of a team to manage the project. |

• Selling the organization on the project approach. |

• Preparation of a preliminary project plan to include a proposal if required by the final project user. |

• Determination of existing needs or potential deficiencies of existing products, services, or organizational processes, as appropriate. |

• Determination of initial technical, environmental, and economic feasibility, and the practicability of the project’s expected outcome. |

• Selection and preparation of an initial design for the expected outcome. |

• Initial determination of expected stakeholder interfaces. |

• Preliminary determination of how the project results will be integrated into existing enterprise strategies. |

TABLE 1.6 Definition Phase Activities

• Full assessment of the project outcomes before major resources are committed to continue development of the project. |

• Identify need for further study and development for the project. |

• Confirm the decision to continue development, create a “prototype,” and assess the full impact of the project for production or installation. |

• Firm identification of the human and non-human resources that will be required for the continued development and deployment of the project results. |

• Preparation of final system performance requirements. |

• Preparation of plans to support the project results. |

• Identification of areas of the project where high risk and uncertainty dictate further assessment. |

• Definition of system inter- and intra-system interfaces. |

• Development of a preliminary logistic support, technical documentation, and after-sale plan. |

• Preparation of suitable documentation required to support the system to include policies, procedures, job descriptions, budget and funding protocol, and other documentation necessary to track and report on the progress being made. |

• Development of protocols on how the project will be monitored, evaluated, and controlled. |

TABLE 1.7 Production Phase Activities

• Identification and integration of the resources required to facilitate the production processes such as raw materials inventory, vendor parts, supplies, labor, and funds. |

• Verification of system production specifications. |

• Actual production, construction, and installation. |

• Final development and approval of after-sale logistic support to include after-sale services. |

• Performance of final testing to determine adequacy of the project results to do the things it is intended to do. |

• Development of technical manuals and affiliated documentation describing how the project results are intended to operate. |

• Development and finalization of plans to support the project results during its operational phase. |

• Build and test tooling. |

• Develop production process strategies to include equipment specification, tooling support, and labor force indoctrination and training. |

• Process engineering changes as needed. |

1.7.4 The Production (Construction) Phase

During this period the project results are produced (constructed) and delivered as an effective, economical and supportable product, service, or organizational process. The plans and strategies conceived and defined during the proceeding phases are updated to support production (construction) initiatives. Other major elements of work carried out during this phase are reflected in Table 1.7.

1.7.5 The Operational Phase

Entry into this phase indicates that the project results have been proven economical, feasible, and practicable and are worthy of being implemented by the user to support their operational or strategic initiatives. Other major elements of work carried out during this phase include those shown in Table 1.8.

1.7.6 The Divestment Phase

In this phase, the enterprise “gets out of the business” that the project results provided. The “getting out of the business” may be caused by loss of customer demand, emergence of new products, services, or processes—all of which have a finite lifetime. Other major activities during this period include:

TABLE 1.8 Operational Phase Activities

• Operating the project results along the intended lines. |

• Integration of the project’s results into existing organizational systems. |

• User field evaluation of the technical, cost, schedule, and economic sufficiency of the project results to meet actual operating conditions. |

• Provide feedback to enterprise planners concerned with the development of new products, services, or organizational processes. |

• Evaluation of adequacy of supporting systems in the organization to complement the project’s operational results. |

• Phase down in the use of the project results

• Development of plans for and the transfer project resources to other elements of the organization

• Evaluation of problems and opportunities associated with the use of the project results

• Recommendations for the management of future projects and programs

• Identification and evaluation for new or improved management techniques

Of course, each project has its unique life cycle. The material that was presented in this section was provided to present a “generic” set of issues involving many projects. The reader should be able to take these generic issues and find out how each of the elements in the five life cycle phases suggested can be used, and also provide a basing point for the identification of the other issues appropriate to a particular project.

1.7.7 Summary

In this section, the concept and processes involved in a project’s life cycle were presented as a useful protocol for the management of a project. A generic life cycle approach was used to illustrate how the use of such an approach can bring about added order and improved protocol for the management of a project. The reader and user of the life cycle approach suggested in this section, should find that the guidance put forth in the chapter can improve the efficiency and effectiveness with which product, service, or process development is conceptualized and carried out.

1.8 PROJECT MANAGEMENT BODIES OF KNOWLEDGE AND PM CERTIFICATION

1.8.1 Introduction

As project management receives more recognition as a profession with its body of knowledge and certification of professionals within the project management community, there is a continuing need to revise and define contemporary theory and practice. This section gives a top-level view of the bodies of knowledge currently in use for training and certification.

Bodies of knowledge circumscribe the knowledge areas that professionals are expected to master and apply to their profession. The project management bodies of knowledge have reached several plateaus over the past 30 years, and continue to grow. National cultures have influenced how the bodies of knowledge have been defined and applied, and there are ongoing initiatives that will lead to new and better definitions and compositions.

A natural result of the recognition of project management as a profession is the establishment of new certification programs. Certification of individuals is accomplished by project management professional societies around the world and at different levels. Individuals may be certified in knowledge of the profession or performance-based competence.

Certification is valued by individuals and organizations because of the confidence placed in an individual’s ability to perform on the job.

1.8.2 Project Management Bodies of Knowledge

The project management profession has been described in the literature for more than 60 years. Bodies of knowledge have been codified into formal documents since 1983 and continue to evolve with the profession. Several professional organizations have developed different versions of a project management body of knowledge.

PMI in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, has been the leader in developing a project management body of knowledge. Other organizations, such as the International Project Management Association (IPMA) in Switzerland, the Association for Project Management (APM) in England, the American Society for the Advancement of Project Management (asapm) in the United States, and the Australian Institute for Project Management (AIPM) in Australia, have developed bodies of knowledge. All organizations refer to their respective bodies of knowledge as standards.

PMI’s project management body of knowledge is the most widely recognized and used. It is officially referred to as A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, or PMBOK® Guide. The 2008 edition defines the body of knowledge in nine areas (Table 1.9).

TABLE 1.9 Nine Knowledge Areas

1. Project Integration Management |

2. Project Scope Management |

3. Project Time Management |

4. Project Cost Management |

5. Project Quality Management |

6. Project Human Resource Management |

7. Project Communications Management |

8. Project Risk Management |

9. Project Procurement Management |

IPMA has developed a body of knowledge called a competence baseline, or ICB, that defines various functions within project management. IPMA has defined its body of knowledge or ICB in 46 categories that provide a scope for the body of knowledge and experience suggested by the association.

The ICB has 46 elements in three categories that are considered by IPMA to be essential for a comprehensive understanding of the project management discipline (Table 1.10).

TABLE 1.10 Twenty Technical Competence Elements

1. Project management success |

2. Interested parties |

3. Project requirements and objectives |

4. Risk and opportunity |

5. Quality |

6. Project organization |

7. Teamwork |

8. Problem resolution |

9. Project structures |

10. Scope and deliverables |

11. Time and project phases |

12. Resources |

13. Cost and finance |

14. Procurement and contract |

15. Changes |

16. Control and reports |

17. Information and documentation |

18. Communication |

19. Start-up |

20. Close out |

TABLE 1.11 Fifteen Behavioral Competence Elements

1. Leadership |

2. Engagement |

3. Self-control |

4. Assertiveness |

5. Relaxation |

6. Openness |

7. Creativity |

8. Results orientation |

9. Efficiency |

10. Consultation |

11. Negotiation |

12. Conflict and crisis |

13. Reliability |

14. Values appreciation |

15. Ethics |

IPMA believes that behavioral aspects of individuals in a project are important for the success of projects; it has defined 15 key elements that describe expected behavior (Table 1.11).

To be considered a competent project manager under the IPMA ICB, one has to understand the contextual nature of projects. This context extends to include programs, portfolios, the permanent organization and the interactions between them. There are 11 contextual competence elements (Table 1.12).