CHAPTER 12

Culture and Globalization

The aim of this concluding chapter is to review the history of globalization and predict the consequences of its immediate future development in order for executives to reflect on the potential consequences in a world that has been changing faster than ever before and will continue to do so geometrically in the years to come.

Contextualizing Background Information

The definition of the term “globalization” has evolved through the years, sometimes including a few notions in it that would afterwards be excluded and vice versa. In spite of all the variations in the construction of the concept, there are at least two common factors that have remained constant across the changing attempts to qualify the phenomenon, namely its origins as a natural step in history, and its unavoidability.

Indeed, researchers agree that worldwide situational characteristics such as relative global peace, the international flow of information, the reduction of trade barriers, the international spread of technology, and the evolution of global market segments have contributed to a complete change in the way trade takes place and this has impacted societies and intersociety links as well. In a nutshell, it is generally agreed that globalization is about a new way of trading without borders that originated out of the conjunction of different historical events and that cannot be stopped.

As an example, Toyne and Walters have defined globalization in 1989 as follows: “the process of focusing an organization’s resources on the selection and exploitation of global market opportunities consistent with and supportive of its short and long-term strategic objectives and goals.” Prior to that, Levin had already defined it in 1983 as the “convergence of the markets of the world,” and Ohmae had already described the process as an “integrated way of production.”

Below are several definitions of the cultural phenomenon.

- Tom G. Palmer of the Cato Institute defines globalization as “the diminution or elimination of state-enforced restrictions on exchanges across borders and the increasingly integrated and complex global system of production and exchange that has emerged as a result.

- Thomas L. Friedman has examined the impact of the “flattening” of the world, and argues that globalized trade, outsourcing, supply-chaining, and political forces have changed the world permanently, for both better and worse. He also argues that the pace of globalization is quickening and will continue to have a growing impact on business organization and practice.

It would be difficult to establish a precise date for the birth of the globalization phenomenon. Some authors would argue that in fact it had originated with trade itself, but as a matter of convenience, and to concentrate on the most influential portions of its historical evolution, we will only describe the main phases having shaped progress in international trade operations from the Second World War onwards.1 In fact, since then, a series of stages have followed and it could be generally agreed that we still find ourselves in the midst of the events. In order to simplify the study of the evolution of globalization and its impact on culture, we will divide the history of the process into phases.

The first phase we consider is called “Home” because the basic trend at that point (immediately after the Second World War) consisted in simply exporting the excess production with no alterations or with just very simple ones. The main idea was to liquidate stocks or to accept orders of an existing product from abroad, but this product would be entirely designed and conceived for the local market. For example, a producer of chairs would manufacture them using local labor, and following specifications that would correspond to the demands of the local public. In case there was an excess of production, it would be sold abroad, but without taking into consideration any adaptations to the foreign public. Producers just “let” foreigners buy their product.

By the 1950s, inspired businesspeople realized that their expertise could be transformed into business opportunities abroad, and therefore they proceeded to the development of units in different locations, which functioned more or less independently, but that were designed to deserve each local market in which they operated. Because each unit would act domestically, but in different locations, this phase in the globalization process is called “Multilocal.” The added advantage of this method was that it allowed the expansion of operations in cases where the local market was saturated or to take advantage of opportunities elsewhere. To continue with the previous example, in this case, chairs would be produced in different places using local labor, designing them to satisfy the needs and tastes of the local markets and to be sold to the local people through the practice of local techniques and aiming at pleasing the local clients and customers.

In the 1960s, developments in travel and telecommunications technology enabled the first stages of global production, the outsourcing of processes and the importing of inputs from economically viable locations. This new way of production allowed progress into the standardization of goods, at a significantly lower price. Applied to the example of the chairs, in this stage a Swedish manufacturer would buy the wood from Finland, the design from Canada, do the assembly in Mexico, and then distribute the standardized product across the world. Due to the diversity and number of countries involved in the process, this phase is called “International.”

By the 1980s, the need for a differentiating factor became key to those wanting to compete on the cost battlefront. Those able to marry quality and low cost managed to gain competitive advantage and were therefore able to position themselves strategically. The main idea consisted in taking the multinational phase one step further by customizing the product or service to particular markets at the last step of their production. This way would ensure that cost conditions were met and that at the same time the offer would match the requirements of the local demand. In the case of chair production, the main processes would be universal (design and production procedures), but at the last points, slight alterations (size, color, distribution systems, etc.) would be made in order to adapt to specific preferences. Because of its intended capacity to meet the needs and wants of every segment, without sacrificing cost-saving standardization, this phase is called “World.”

By the year 2000, economic blocks had relatively stabilized in terms of free circulation of goods and workforce, which accelerated the division of tasks into high versus low added value producing. Post-industrialized nations initiated a process of relocation of their manufacturing activities abroad, keeping the core competency at home, mainly concentrating on “brainwork” and replacing factories in foreign locations. Ecological issues start to gain importance in the minds of citizens and this increased sensitivity promoted the evolution and acceleration of the same dynamics. As creativity is considered as a key success factor in this phase, cross-cultural thinking is promoted and developed nations start to compete in the attraction and retention of the brightest minds across the globe. To continue with the same example, in this case the chair would be designed in Sweden by the best designers from everywhere in the world, produced in China and distributed using an American company. This phase is called “Decentralized.”

The most recent developments in trade have allowed the development of networks of thought, which, distributed across the globe, act as the concentrators of know-how and creativity, which will then be applied in the production and marketing of goods wherever manufacturing takes place. Because the way of working implied in this new phase is much decentralized and operates through networks, it has been named “Networked.” In this sense, thought occurs wherever the brains are located, which act as “centers of knowledge,” operating in very small and reactive structures all over the world, which concentrate and dissolve as soon as the tasks and projects are accomplished.

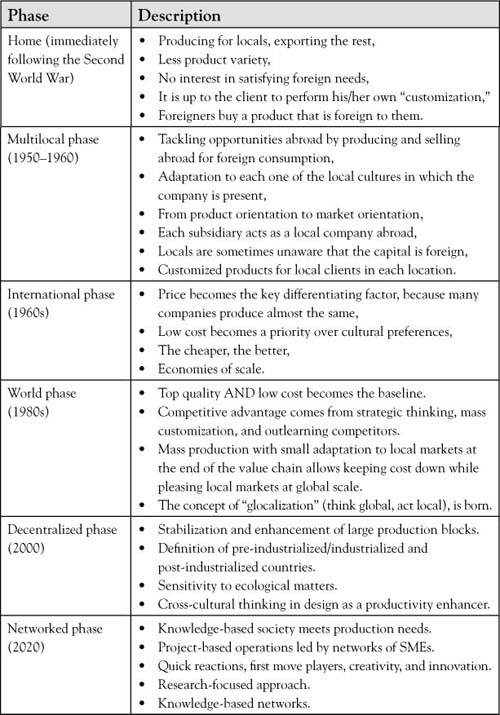

The table below synthesizes the evolution of globalization since the Second World War providing main characteristics of each phase:

The different stages in the globalization process have affected cross-cultural management differently and different cultures have faced this phenomenon in very different ways, according to their own characteristics and socially developed tools to face the issues relating to changes in ways of working and the evolution of international trade.

As an example of the previous statements, we can quote another Wikipedia entry, which also quotes an interesting point of view relating to globalization.

Finally, Takis Fotopoulos argues that globalization is the result of systemic trends manifesting the market economy’s grow-or-die dynamic, following the rapid expansion of transnational corporations. Because these trends have not been offset effectively by counter-tendencies that could have emanated from trade-union action and other forms of political activity, the outcome has been globalization. This is a multi-faceted and irreversible phenomenon within the system of the market economy and it is expressed as: economic globalization, namely, the opening and deregulation of commodity, capital and labor markets which led to the present form of neoliberal globalization; political globalization, i.e., the emergence of a transnational elite and the phasing out of the all of the statist period; cultural globalization, i.e., the worldwide homogenization of culture; ideological globalization; technological globalization; social globalization.

The different phases in the globalization process have impacted cultures involved in the process in many ways. Whereas in the domestic phase, dealing internationally consisted basically in speaking a common language at least basically or communicating through translators on very specific and objective matters (i.e., prices, delivery options, conditions, contract clauses), other phases have required the enhancement of a more evolved communication arena.

For instance, in the multilocal phase, some companies decided to delegate responsibility for the operations to local managers (this was the preferred American style), and these agents also operated as the interface between headquarters and the subsidiaries, absorbing most of the cross-cultural biases and disruptions. Other companies (in general this was the preferred French style) sent expatriates to deal with local uses and operational standards, bearing in mind that the general practice designed at headquarters was the one to be put into practice at local level. In any case, each subsidiary would very much act local and also think local and headquarters would not mind very much about specifications or ways of doing things abroad, as long as the financial objectives were met. The impact of globalization on society up to this stage was not very important, as it implied little work mobility and no change in production processes or management procedures.

It was probably during the multinational phase that globalization produced the strongest impact on societies, as the production patterns were applied universally, but designed from headquarters. Companies started producing gains that allowed them to expand without borders and enhance their overall power and governmental lobby capacity as never seen before. Many consumer products were standardized and consumed in similar manners across the globe and labor was hired where it was cheaper, not always considering the impact of this choice on local welfare or even sometimes human rights (i.e., child labor was employed, health and safety conditions of employees were often not respected, etc.).

During the global phase, quality became an issue, imposing new regulations on international producers. Even if the international consumers felt tempted by the cheaper products during the first stages of globalization, soon they became disappointed by the poor quality of what they bought and this reality gave a new kick to local small manufacturers. Once the globalization process was perfected, numerous SMEs across the globe disappeared, remaining unable to compete with the giants, causing unemployment.

The problems that arose with globalization during the first phases, in particular during the multinational phase mostly concerned underdeveloped and developing nations. The most recent stages, nevertheless, mainly affect the most developed countries. The decentralized and the networked phases of globalization brought with them the need to exploit the brainpower of nations to their maximum in order to generate and support the knowledge based society. In this sense, as the manual operations are executed in specific locations, leaving the high added value activities to concentrate in headquarters (postindustrialized countries), there was a two-way flow of population: unqualified workers received incentives to move to destinations where the factories were, and at the same time, qualified brains were welcomed by postindustrialized nations, who wanted to attract those able to perform high added-value tasks.

The networked phase, though, because of its location independent characteristics, does not call for the physical presence of the workers where they perform their professional tasks, and therefore should reduce the amount of migration through different methods. Strategically positioned networks concentrate brainpower in locations worldwide and these units interact on short-term projects worldwide. Even if the networked phase mostly concerns qualified workers, this arrangement will probably equally concern the less-qualified portion of the population, as developments in technology will progressively allow the replacement of routine jobs currently done by men, by machines.

The new landscape beyond 2010 will probably be designed by networks, which as predicted will act beyond national borders and the ruling class will probably be the most qualified and powerful, or at least the one that would have accessed knowledge and know-how to the point of becoming indispensable for the networks.

Many have wondered whether globalization would destroy multiculturalism and the answer to that question cannot easily be found. Some authors like Geert Hofstede may state that globalization can only affect practices (the way we do things), but not values and therefore the inception of new products and techniques would only have a limited impact on culture. On the other side, mobility will be enhanced and networks will be established, which would indicate that probably culture would be more affected by the fact that one belongs to a network or not, rather than by nationality.

Multicultural regions like the EU are trying very hard to find a common denominator in order to develop a common sense of belonging across member states with varied levels of success. On one side, the Christian tradition was intended to be a strong linking factor, but the incorporation of Turkey within the block would strongly challenge this fact. Perhaps it is the idea of a common future together that would link countries, or the facilitated internal mobility could at some point generate a powerful sense of unity. Whether this unity will ever mean the loss of identity is arguable.

Pressure groups have wanted to limit the extension of the impact of globalization, but the phenomenon is just unavoidable: for as long as technology is put in hand to disseminate ways and uses, globalization will continue to expand. In any case, nations have been subject to the invasion of other cultures for centuries and they are in fact the result of the conjunction between the old and the new—whether the “new” is imposed or just voluntarily acquired. Just as an example (amongst thousands of others), no matter how unified, unique and ethnically homogeneous a nation like France could seem, it is just the result of the conjunction of a huge number of cultures that have occupied its current territory through the centuries: Romans, Celtics, Germanics, Vikings, Gauls, Normans, and so on have contributed to change and to stability and to what we know today as France.

Perhaps what is essentially different since the big impact of globalization has started to take place is the way in which change is absorbed. Until now, the incorporation of new uses and costumes was confined to the specific geographic territory in which it took place (i.e., the Romans invade Gaul and then the Gaul discovers pizza), but the new practices did not go beyond each geographic confinement individually. Contrary to that, nowadays incoming factors (inventions, technology, Facebook, iPads, etc.) affect the globe in its entirety at once, on the spot and at the same time and in the same way and therefore evolution tends in many ways towards the same uses and customs, or at least to the same practices across the world, at the same time, as if a huge force was invading the planet as a whole.

This very particular aspect of the way in which change in cultures takes place due to technological progress (which recognizes no land borders) has led and continues to lead to two very specific and very particular characteristics of current times: (1) culture will increasingly develop in terms of subcultures and less in terms of national cultures and (2) the big social and economic differences will not be geographical, but knowledge-based.

The first effects of these changes are visible already: for instance, changes in education start to occur. Traditionally in most countries primary school education was in many ways a preparation for war: from the study of national anthems and other battlefield songs to the presentation of the glory of the nation through the victories of its heroes, children from almost every country were taught that they were part of a group to which they owed loyalty in exchange for protection. Most of us have been brought up that way. A more creativity-enhancing, free-thinking, culturally friendly, nonracist education is being generated in order to respond to the new needs of the world, which tends towards an innovation-led paradigm as opposed to a field-owning regime which might at some stage and with little anticipation call for the blood of youngsters to defend the common property.

In the old days in which immigration only took place gradually, it was easier to recognize foreigners: in many cases they looked different. It was easy to create stereotypes, to judge and to set areas of the population apart. As the world develops towards innovation and the knowledge based society, the differences that used to be visible become unreliable: nations are multiracial and in order to attract the best brains from wherever they come from, the way a person looks will less and less be considered as a reliable indicator of his/her position in society, his/her wealth, or his/her background.

For years and years, the notion of “security” has been strongly linked to that of “nationality” or “inhabiting a land.” Most basic rights are acquired through a nationality. Our nation’s reason to exist is that it provides safety and security, plus a sense of belonging to those constituting it. This is part of the social contract that we have been socialized upon. Within the new circumstances, with networks assuming the role of job providers and status warrantors, the fact is not so certain any longer. Some nations (the UK for instance), start publishing brochures in which they mention a new concept “one needs to deserve to be a citizen”... this implies a huge change in the collective mental programming. People do not just “obtain” a nationality, they need to actually be worthy of it.

Terrorism has somehow contributed to change in mental programming. The “enemy” might be within us. At first, terrorism was linked to Muslim extremists, radicalists, or specific groups outside civilized society. Until recently, criminal acts were countered by nationalism, which would correspond to the traditional reaction of land versus enemy (i.e., the United States versus Bin Laden). But since terrorism is now becoming the action of individuals within society (i.e., Anders Behring Breivik’s mass murder in Norway), the old ways of patriotically aligning against the common foreign enemy seem to have lost their efficacy. And other forms of security impose themselves (socially accepted technological espionage being one of them).

When living in conditions in which change is happening faster than we can realize, where parameters are evolving at such a rate that we cannot follow, and at times where everything we had always considered as true, may simply be not so any longer, societies need to adapt and mentalities need to change.

Nations will probably not define us and protect us for much longer to the same extent as they used to. Having lived on a piece of land for many generations may no longer guarantee safety, security, or even identity. Identities may need to be self-constructed to a higher extent and it might become necessary to work to deserve to be part of a group that provides for some of our needs.

So, how will humanity satisfy its own need for identification, social belonging, and interaction with peers? For years, the main socialization factor was belonging to a culture, a country, a region, and so forth, and identity was made visible through symbols and external materialization of them. Globalization has an important influence in turning most of these symbols into anecdotal picturesque objects that remind us more of the history of a place than of the history of people themselves.

We find ourselves at present in the midst of a transition from a situation in which nation states provide safety and security, identity, and status; to a new one in which all these assets are to be merited and the networks to which one is linked to determine each one’s position in society (which is borderless) and grant the sense of belonging. Safety and security does not come from solidarity towards those who share the same nationality, but from the fact that our lives become visible to everyone through the information we volunteer through our computer at every moment.

The transition is harsh to go through, as it leaves us frozen in front of a new framework of mind to adapt to and to operate from.

In this sense, collective cultures may need to alter their criteria of connections in order to adapt them to the networks that will determine the new social ruling; masculine societies will have to recognize that in order to support the new ways of production gender can no longer be a barrier if we are to maximize the use of the brainpower that exists in each block; internal locus of control cultures will need to depart from their need to adapt to the unknown, rather than mastering it; synchronic cultures will need to focus on the future, rather than on the past; status will be more achieved than ascribed; power distance will be shorter and emotionals will need to control how they express themselves, as information that is put online will remain on record forever.

Using This Information

To reflect and get ready for the years to come!

Discussion Point

Now review the following statements and comment on them. What do they mean? Who could have said them?

- “Think global, act local”

- “The doctrine of free trade, if applied globally, will be a disaster”

- “Economies should not be self-serving structures, but directed at promoting the stability and contentment of the societies within which they operate”

- “Europe faces a future of unemployment, poverty and social instability”

- “Britain will become the Mexico of Europe”

- “A reason for this is our quasi-religious belief in free trade. A moral dogma which was born when Britain was the manufacturing centre of the world”

- “A world of fence-off regions with economies that reflect local conditions, cultures and needs”

Get Into Globalens.com

Go to the www.globalens.com web page and access the following cases:

- Detroit Motors and General Auto: A Case Study in Globalization, Outsourcing and Automation

- Western Union: A Case for Global Expansion

- Globalization Comes to Nakamura Lacquer Company

- Jim Thompson Thai Silk Company

- NAFTA Arrives at Maxwell Tomato Farms

- Vostok Watches

Now compare the previously listed cases of companies entering the globalization process and determine in which aspects they were successful and in which they were not. What are common issues that appear in all cases? What are particular/industry specific matters?

Prepare a comparative table like the one below and then elaborate in writing.