CHAPTER 11

Cross-Cultural Teamwork

The aim of this chapter is to apply the previously discussed frameworks for cultural analysis to predict and be able to deal with the most common problems relating to working in or with international teams.

Departing from a model describing different types of teams, we will develop on what would be the right attitude when these teams are composed of people from different cultural backgrounds, thinking, feeling, and acting according to their own mental programmings.

Contextualizing Background Information

Driven by the rise of the multinational enterprise and new technologies, cross-cultural teams are a common feature of international business. A cross-cultural team is a small number of people from different cultural backgrounds, working towards a common purpose. A key characteristic of a cross-cultural team is cultural diversity, which relates to the degree of cultural difference represented in a team.

Cultural diversity differs across cross-cultural teams. Essentially, the degree of a team’s cultural diversity depends on two things. First, it depends on the cultural distance between the members of the team. Here, cultural distance relates to the perceived distance between two cultures: the more characteristics that cultures have in common, the smaller the cultural distance, the fewer characteristics that cultures have in common, the greater the cultural distance.

Cultural diversity in teams also depends on the number of cultures represented in the team. The more cultures included in a team, the more diverse it is going to be. We can differentiate between token teams, bicultural teams, and multicultural teams. In a token team, all the members but one come from the same national culture. Bicultural teams consist of members representing two distinct cultures. The members of truly multicultural teams come from three or more cultural backgrounds.

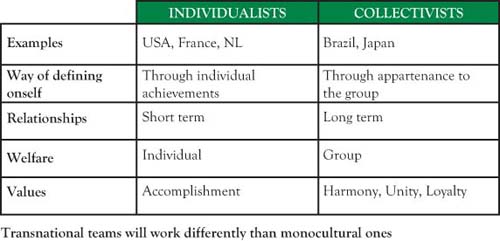

Cross-cultural teamwork is not restricted to transnational teamwork, meaning teamwork between people from different countries. Cross-cultural teams can also be understood in a wider sense. As explained earlier in this book, we can talk about different layers of cultures. So, below the national level, we can also see regional cultures, industry cultures, corporate cultures, and occupational cultures. In this sense, we could feasibly talk about cross-cultural teamwork within individual companies. Figure 11.1 points out potential sources of miscommunication in pluricultural teams, through examples based on collectivist versus individualist cultures.

Take the example of a project team established by a company to market a new product. The team might bring together representatives from the finance department and the sales department. The members of the finance department might be careful and conservative in terms of spending. By contrast, the members of the sales department are likely to be keen to spend more money as this may result in more sales. So, these two distinctive departments bring their own cultural baggage to the team. The finance department appears to be more averse to risk than the sales department.

Types of Teams

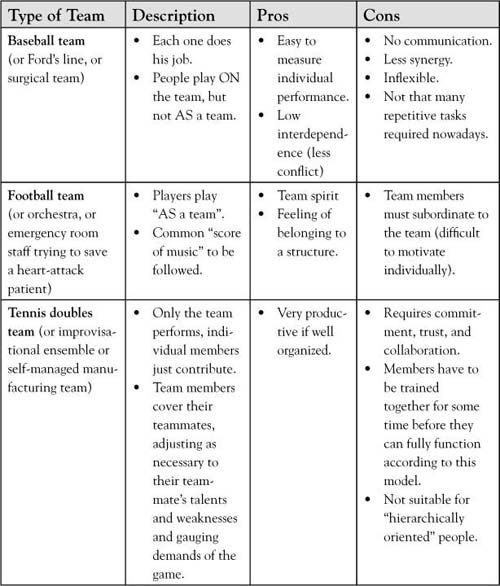

In her article “Managing your Team,” published by Harvard Business Review in 1994, Linda Hill1 put forward three different types of teams, calling on sports metaphors. The intercultural factor has a different impact on each one of the following types of teams, as the required interactions and the dynamics vary in intensity and in frequency.

Basketball Teams

Hill called the first type she identified a “Basketball team,” because in it everyone does his/her job independently, working “on” the team, as opposed to “as” a team. It is the typical case of factory’s production lines (Taylor style) or a surgical team performing an operation in a theatre.

Because even if the jobs are interdependent, they still are independent; in this type of team it is easy to measure individual performance and this leads to less conflict because the level of interaction is lower. In this sense, this way of operating is preferred by achievers, masculine cultures, and individualists, because they see in it a chance to show their capacity and shine when being pointed out as the stars of the endeavor.

People from high uncertainty avoidance cultures also prefer this system, where the norms are clearly indicated through job descriptions and it is easy to use the operations manual to defend oneself when something goes wrong. Because the basketball team is very well structured, it suits the power distant, and the ascribers, because they like the hierarchies that the controls that are necessary to implement this system of work impose.

Neutrals may like it as well, the same as universalists, because the level of conflict is reduced by setting of profit units. If everyone knows what his/her duties are and it is visible when someone did not comply with the norm, then there is little room for misunderstanding or mutual blame. The “norm” can easily apply to everyone.

American Football Teams

The second type of team that was identified was the American football team. In it, players do their job “as” a team (as opposed to “on” a team), as if they had a common score of music to be followed. There is a strong feeling of team spirit and belonging in this type of team, in which every one has an important contribution to make. On the other hand, each one of the members must subordinate to the interests of the group, and individual contribution is difficult to identify. The victory is a common victory, and so is the defeat. Unless there are very strong ties and commitment to the whole, it is very hard to motivate individually.

This type of team is very common in collectivist ascribed cultures, where individual achievement is perceived as a motive for envy and shame, rather than as the basic requirement for professional progression.

Uncertainty avoidant cultures may find it hard to accept this type of work, because in times of conflict, it would be more difficult to identify the causes of low productivity or of malfunctions, so a lack of method to identify actions on a particular basis may sound disruptive and cause concern.

Individuals from high power distant cultures may appreciate this type of team as long as it occurs within the same level of the hierarchy. For example, in Japan, this type of team has allowed the flourishing of very successful production methods, such as total quality management or just in time, because everyone involved in the operations assumed a role to play and went along with it very seriously. The failure of a company was understood as everyone’s failure regardless of their level within the hierarchy. Nevertheless, the hierarchy was always seriously maintained, and relationships between the higher caste and the lower ones are strongly based on trust, loyalty, and honor.

This type of game requires a strong commitment between members, and being ready to “give one for the team” more often than not, which makes it much more appealing to members of diffuse cultures (in which every action affects all levels of life and therefore it makes sense to “give more than what the contract says”). Also, this type of team dynamics is very compatible with long-term orientation cultures, because constituting a team that works well and in which “all for one and one for all” is the rule, takes time. People from achieving, sequential cultures would feel very disappointed if having to work under such a rule, because it would seem quite frustrating to them having to put their egos in second place.

In emotional cultures, the fact of having to put feelings at stake in every aspect of life makes this team style a good arena for devoting passion to the work done together, but communication needs to be handled with care, because the loss of harmony could cause serious disruptions to the proceedings and work outcomes; so high context exchanges need to take place, not to have anyone be vexed or offended by coworkers.

Tennis Doubles Teams

The third type of team identified by Hill was the tennis doubles team. Within this arrangement, only the team performs. Players just contribute to the common score. Team members cover their teammates, adjusting as necessary to their talents and weaknesses and acting according to the demands of the game.

This type of team is very productive when well organized, but it requires collaboration, commitment, and trust. Members need to have been trained together for some time in order to be able to work smoothly together. Within this arrangement, hierarchies matter more than anything else.

This sort of arrangement suits particularistic people, as there is trust involved. There is a need for quick reaction, therefore the checking for universal rules to be applied could take precious time that ought to be otherwise used.

It is difficult to think in terms of short-term orientation when it comes to having tennis doubles teams work well, mainly because it becomes necessary to develop knowledge of how the other person plays as well as ways to guess what the other person is thinking before action takes place.

Communication in general takes place implicitly, so the preferred communication style is high context. The tennis doubles teams would certainly suit achievers, as long as the victories allow for them to shine individually as well; but is not good for power distants, because quick reactions are expected and this is not possible to achieve when hierarchical procedures come to block natural developments instead of reinforcing them.

New Ways of Working

Postindustrial societies are more and more involved with new ways of working, which require the constitution and dissolution of teams on a short-term basis. Those teams tend to be led by generalists, who coordinate the work of specialists. For instance, to create a new drug to fight cancer, a specialist manager will be called to lead a team consisting of a well-known oncologist, a specialist in biotechnology, drug marketers, etc. These specialists from anywhere in the world would get together around the generalist to work on a specific project, which will soon after be dissolved. They may or may not work together again.

The new ways of working call for project orientation on very immediate and specific areas, and people involved in it need to be prepared to act in a very specific way. Relationships are meant to be short-term and communication needs to be explicit. Achievers may feel at ease as long as they take tangible credit for the outcome.

These new ways of working are difficult to deal with for people with high power distance orientation and for uncertainty avoiders, because there is a need for quick reaction (which hierarchy would slow down) and there is no chance of blaming others: the risks need to be taken and the consequences follow on the team, not on individuals.

Collectivists, synchronics, and people from diffuse cultures generally feel uneasy within these arrangements, because of their impersonality. They find the coldness of the short-term groupings annoying and sad. Ascribers resent the lack of recognition that should come other than from achievements and universalists believe it is hard to function sometimes without specific rules to be followed.

Teams of Teams

Even if there are all types of teams in all cultures, and even if subcultures such as industry or company can influence the selected type of team more than national culture, it would be worthwhile analyzing what sort of problems could arise when people used to or preferring a particular type of team are forced either to change into another team framework or to merge with others who are used to working with a different type of team. How would a basketballer manage to play a doubles tennis team? How would a footballer score at basketball? How would any of these sports-businessmen score at new ways of working?

For instance, when having to work together, people used to operating “basketball style” may find those used to the “football style” casual, noisy, and disorganized. “Basketballers” would be looking for a set of tasks clearly identified, scheduled, and regulated, and to be performed individually. They would also be wanting to know what is expected from each person and how performance is to be assessed and compensated. “Footballers” would find “basketballers” annoying and bureaucratic, egoistic, and unfriendly.

Basketballers would also find the tennis players casual and disorganized, always wanting to do new things without following a procedure. Roles could change automatically without any previous discussion and the ball would just come and go too quickly for them to react in a rational and professional manner. Tennis players would find basketballers slow in reaction, boring, bureaucratic, and hierarchical.

If forced to work under the new ways of working, basketballers would be annoyed by the lack of structure and by the fact that they would have to make decisions on the spot, without following a specified procedure. Most probably, basketballers would dislike innovating or listening toothers, and would require a boss who is a specialist, not a generalist, because someone who does not know better than everyone else would hardly be legitimate as a proper superior.

When footballers interact with tennis players, both teams would appreciate the coordination and mutual support, but the latter would resent the lack of flexibility and coordination from the other side. Footballers might find tennis players cold and lacking a centralized structure or “common generalized feeling of belonging.”

But footballers may find the hardest of times dealing with the new ways of working, because the huge feeling of belonging from years of working together and developing mutual trust would just not exist in this scenario. Footballers may find the fact of having to reunite and disintegrate groups on short notice quite annoying and sad. The fact that in the new ways of working individual achievement is valued and recognized would seem egoistic and naive for the group ambience to the footballers. People involved in the new ways of working would find footballers unproductive and oversensitive, and perhaps not very profit oriented, which would require some dynamism and responsiveness.

Finally, when confronting or trying to have tennis players adapt to the new ways of working, a problem may arise in terms of having to adapt to other players rather soon and then having to replace them with others on the next project. Tennis players would need time to adapt and get to know their partners as much as possible before developing lasting work relationships that are to derive in sustained performance.

Identifying Cross-Cultural Teams

Below, employees talk about their experiences of working in multicultural environments. Some of the problems presented derive from national culture differences, others from differences in subcultures. Frameworks for cultural analysis and the types of teams described above help us identify the key issues and suggest avenues for resolution.

An American engineer working in Stuttgart

It’s something I’d never admit to anybody here at work, but I really do feel happiest when I’m working on my own. I like to be in control, and I like to be rewarded for my individual efforts. I don’t like the idea of my bonus being partly dependent on my colleagues’ performance. For all I know, they could be spending their days taking endless coffee breaks.

This typical member of an individualistic, highly achieving culture would probably feel more at ease working under a “tennis” setting than under the “football” or the “basketball” environment he/she seems to have been pushed to join.

Probably his or her colleagues would not appreciate his/her disrespect of the norm (that perhaps would allow the coffee breaks) that bothers him/her because he/she feels that it prevents him/her from taking control (internal locus of control).

This engineer’s supervisor should perhaps consider either finding a way to recognize the particular effort of the engineer, give him/her every opportunity to develop on his/her own and slowly introduce him/her to a different view which implies that sometimes coffee breaks have a meaning that goes beyond the mere refreshment (i.e., valuable information is usually disseminated informally during coffee breaks, conflicts arising from the need to work together are dealt with during coffee breaks, etc.).

Unless the supervisor makes an effort to reconcile the two ways of working, the company may be losing a valuable asset and/or the engineer could experience his/her stay in Stuttgart as a painful, horrible experience.

A PhD student from Brazil studying in Sweden

The working atmosphere here is pretty miserable, not at all like back home in Brazil. Everybody spends the whole day working alone in their offices. They keep their doors shut, so you feel bad knocking and asking for help. My colleagues never ask me what I’m doing. How the hell do people get anything done if they don’t interact with each other?

In this case, we have a footballer suffering from having to play on his own sometimes. His collective, diffuse, synchronic, particularistic upbringing must be making it difficult for the Brazilian student to play a different game, perhaps more individualistic and above all, neutral.

A good student advisor would explain to this student that the tacit rule in Sweden is “We will help you when you need it, but you need to say it very clearly when you do,” and that asking or offering help for things that one could do on one’s own anyway is not considered as a relationship building exercise, but a sign of weakness.

Perhaps this student needs to be introduced to the Swedish social circles where fun takes place, as in specific societies there is a place for joy and a place for work. This Brazilian student may have only come across the second one and therefore he must feel very lonely, sad, and depressed. Unless someone at the university takes charge, the institution may well lose a good potential researcher who would just feel too homesick at some stage to finish his thesis.

An American software engineer, Santa Clara

The company hired a bunch of Puerto Rican software engineers. We went out of our way to avoid working with them. Everyone knows that the quality of education in Puerto Rico is poor compared to the States.

Here is the typical example of the non-sports (wo)man. And it is a very common case. No game can be played with someone who is not interested in playing.

Unless the supervisor or the human resources department of this company decides to firmly invest in training its American employees, they will have to face huge financial loses (in lawsuits, loss of productivity, loss of good workers, etc.).

Following the training, mingling exercises should take place, in which coworkers should talk about their experiences, their studies, and share knowledge.

A Brazilian on his experiences of working with Americans

Many times I felt I didn’t have the words to say what I was thinking. When I had meetings with the Americans, they would always tend to take the lead, which was understandable but also disappointing because we were at the same level in the company. I had some very good questions to ask, but I just lacked the confidence to express myself.

This is the same case as above. Parochialism in business is the result of poor education most of the people who graduated before the Internet have been through. This statement may be controversial, but very few people who graduated before 1995 are ready to work internationally, simply because they did not have the opportunity to understand that intelligence is not the monopoly of any country at all and that in every nation there are excellent schools and professionals.

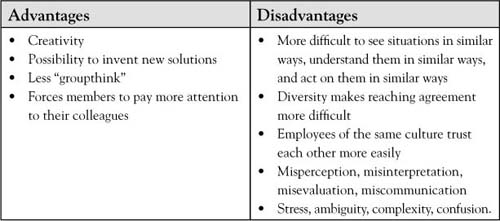

Lack of preparation to deal with international coworkers in this case would certainly lead to the loss of great ideas and the perpetuation of “groupthink” within the teams. The opportunity cost involved is just too huge to be absorbed. Any competitor who is able to better manage his/her human resources would profit from the situation to do better.

An American on her experiences of working in a Japanese team

One of the hardest lessons for me was learning that, when the Japanese say ‘yes’ they just mean ‘I’m listening to you.’

When working within football teams, it is very important to keep harmony alive and to reinforce it by avoiding conflict at any cost. A football team with players who detest or boycott each other can never win.

For this American, communicating with high context must have been a challenge, because the answers would take longer to be understood. But they eventually would.

A Swede discusses designing products in a multicultural team

We traditionally carried out product design at our Stockholm headquarters. Once, we brought in an international team to discuss the design of a new allergy product. Due to extreme differences in opinion on what constitutes good medical practice, the team designed the new product with maximum flexibility to suit the requirements of each country. We later discovered that the greater flexibility was a huge advantage in developing and marketing a wide range of internationally competitive products.

Here is a team that managed to create a new rule for all to play. When taking advantage of diversity, instead of ignoring, drowning, or fighting it, they made the best out of it. This company would certainly be stronger, more innovative in the market, than the ones discussed above. The feminine characteristic of Sweden has certainly helped in having every member express themselves, rather than assume that only one view should be imposed on everyone participating.

A Brit talks about a team-building exercise organized by French colleagues

The whole team was taken out to the middle of the Arabian desert. When we reached our final destination—a tiny village in the middle of nowhere—we found a jeep, a map, and a note from a French manager giving us one week to find our way to Riyadh. What a complete waste of time! We were keen to start work on formulating strategy. We didn’t have the time to be fooling around in the desert.

The Brits wanted to play tennis, or use new ways of working. The French were trying to build a football team. So the training for a football team was to put everyone in a hard situation and get them sort it out together. By the time everyone had reached Riyadh, the team would be expected to be solid.

There was no interest from the French to have the team members formulate strategies. Strategies are formulated in France by the top members of the hierarchy, not by the lower managers. The lower managers just need to get along and develop a sense of belonging that will lead to loyalty.

The predicted result of this experience is two teams within the team: the British talking English and the French talking French. The French will probably discuss the strategy to get to Riyadh (and not the company strategy), the Brits would probably be criticizing the French and using common sense to find some sort of camel somewhere or call a taxi from their mobile phones.

A French woman recalls a project kick-off meeting in Washington, DC

I found the whole experience disconcerting. We hardly had any time to introduce ourselves to each other. Within minutes of arriving at the hotel, we were expected to sit down and work closely with these apparent strangers on developing a new financial strategy.

The French lady wanted to play football, but in DC they were playing new ways of working. This is a very disappointing game for a person from a diffuse culture, who needs to know people before trusting them, and to trust them before working with them productively.

A German technician working in Dallas

The problems began in the planning phase of the project. I wanted to use my expertise to fully understand the problem we were addressing. Instead, I was given specific targets and was expected to reach them in a very short time indeed. But were these really the best targets that I could have been given? For the sake of speed, a thorough analysis of the problem did not take place. How are we expected to do quality work on this basis?

The German technician wanted to play basketball on a tennis court. Now he is complaining because his Armanis are covered with clay.

In order to react quickly in tennis courts, it is necessary to assess the situation very fast and to act half by hunch, half by strategy. This is why trial and error is the preferred way of learning in cultures like the United States.

The German way of thinking is very deductive: first comes thinking, then comes acting. But in a tennis court, analysis can mean paralysis, therefore it is much more convenient to adapt to a fast-reaction mode and go with the flow. And this can certainly be disruptive and disturbing to a German mind.

An American technician working in Stuttgart

We met to define our overall strategy. I was expecting a brief two-hour brainstorming session—we’d develop some general solutions, select the best ones, and delegate tasks. Instead, we were sat there for three full days. The Germans loved to see themselves as ‘Volk der Dichter und Denker’ (people of poets and thinkers). But we don’t have to endlessly dispute everything and act like a bunch of little Immanuel Kants to get a product to market.

This is the same problem, the other way round. The tennis player found himself in a basketball court, before the game, discussing the strategy with his colleagues. He just did not see the point in doing that.

A German technician working in Dallas

I was always astonished to see how quickly my American team leader reached a decision. He briefly thought about a problem, announced his decision, and that was it. The other team members just accepted his decisions without ever questioning them. I came to the conclusion that working life in America is much more authoritarian than it is in Germany. This actually came as quite a surprise to me, as I wasn’t expecting this.

Americans understand that sometimes reaction means no time for discussion. And in that case, the person who is considered as the most likely to make the least errors is the one expected to make assumptions and go for a trial.

Using This Information

One of the hardest tasks for international managers to perform is probably the management of intercultural teams. And the least technical, more values-sensitive the task, the harder it becomes for a manager to have a group to act in productive harmony.

Understanding that not all members of an intercultural team could be “playing the same game” could perhaps help their coach realize that there should be some rethinking of the basic rules to be done, some talks to be organized, and some follow up to be undertaken.

Exercise

Imagine a situation in which you are to manage an intercultural team comprising members with diverse perceptions on how to work. Propose solutions to make such a team uniform.