CHAPTER 4

Other Frameworks for Cultural Analysis

Contextualizing Background Information

Besides Geert Hofstede and Fons Trompenaars, other authors have developed theories in which they present frameworks for cultural analysis. The classifications originate in the social sciences and some of them are far more dated than the ones produced by business anthropologists. Even if it has never been explicitly acknowledged, most of the frameworks used in business derive from dimensions used in anthropology; therefore, most of the classifications overlap across authors.

The aim of this chapter is to add a few more frameworks to those already developed in previous chapters, in order to present readers with the most complete overview on dimensions for cultural analysis.

In subsequent chapters we will use these dimensions as tools to describe, predict, analyze, and comment on intercultural behaviors occurring in international business.

Frameworks for Cultural Analysis by Major Authors

The chart below lists different frameworks for cultural analysis by different authors. This classification can be useful to identify the dimensions that have not been covered either by Hofstede or by Trompenaars and to develop on them. In most cases, all authors have given similar names to similar frameworks, but there are cases in which they have not. For example, Trompenaars’ diffuse versus specific dimension was called space public versus space private by Adler, and space (personal/physical) by Hall. Another example is Adler’s being/doing, which carries the same significance as achievers/ascribers by Trompenaars.

Authors |

Frameworks |

Schein1 |

Relationship with nature |

Trompenaars2 |

Relationship with nature |

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck3 |

Relationship with time |

Adler4 |

Human nature |

Hall5 |

Space (personal/physical) |

Hofstede6 |

Uncertainty avoidance |

From the above table, it is possible and easy to identify which frameworks still remain to be treated.

Frameworks for Cultural Analysis and the Authors Who Developed on Them

The table above helps us notice there are two frameworks that are addressed neither by Hofstede nor by Trompenaars. These frameworks are: language (high versus low context), by Edward Hall and human nature (by Schein and Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck).

Language (According to Edward Hall)

Language can certainly become a barrier when dealing cross-culturally, but paradoxically, it is not the highest obstacle to overcome in cases where communication needs to exceed mere formalities. The language barrier in many cases can be easily overcome by means of the actions of a good translator.

Meta-language barriers, on the other hand, are much more complex. They refer to ways in which we express our thoughts and feelings. We have already discussed the emotional versus neutral dichotomy in previous chapters, but this is not the only theme in which cultures may vary. This particular framework relates to differences in what we say and what we mean and how these differences are expressed across cultures.

In an attempt to understand cultural mismatches in communication patterns, Edward Hall has developed a specific framework called high versus low context. People from low context cultures usually say what they mean and they mean what they say. Their communication style is very direct and ambiguities are meant to be minimized, as the key issue is to convey a specific message with concrete information. Clarity is important and also considered the main component of successful exchanges. One could think that communicating with these cultures should be simple, as there are supposed to be no hidden meanings, but to high context cultures such an approach to exchanges comes across as aggressive and pushy, almost disrespectful.

In high context cultures which are also external locus of control oriented, it could be considered as “arrogant” to assume that one can determine a fact, put it into words, and convey it to someone else, as reality is quite hard to ascertain and to define in particular words. In other high context cultures, like in the UK in particular, politeness is important and playing a game of understandings and sub-understandings can be considered as a sign of refinement and sophistication. In general, conflict is to be avoided by all means in high context cultures, therefore frontal expressions of views or feelings without sugarcoating are to be avoided.

In low context cultures people use words more than any other tool to communicate. In high context cultures words are just a tool amongst others: people communicate as well by producing situations, through their appearance, with tonalities of voice, with symbols, and with gestures. Harmony, politeness, and keeping the relationship going are considered as keys to success (which is more likely to be obtained through diplomacy than through fighting), so it is very important never to hurt feelings. Words sometimes can be crude, therefore it is tacitly agreed that keeping them to a minimum could be a healthy option and socially satisfactory.

A scheme representing rhetorical styles commonly used in different cultures can be found at http://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr6/pistillo.htm (see Fig. 1 Context ranking of cultures7).

Whereas in some cultures it is important to “pass the message with no ambiguity,” in others “to save face and save other people’s face” takes priority. Being too direct could be perceived as insulting or barbarian in high context cultures. It might mean that there is no interest in pursuing the relationship. In private relations, it can be hurtful and nasty.

In North American, Germanic, and Scandinavian cultures, people prefer to communicate directly. In Latin cultures, it is customary to use a more indirect way of communication, and South East Asians prefer a very indirect “beat-around-the-bush” style.

To the question “Would you like to go to the cinema with me today,” a person willing to decline the invitation would communicate their decision in very different ways.

A Scandinavian or a Swiss would simply tell the bare truth: “No, thanks, I shall not go to the cinema with you this time because I do not feel like watching a movie today,” a South American would probably respond: “Oh, I’d love to go to the cinema with you, but I feel really tired, I have been taking this new medicine that knocks me down, it is a real pain! Please do ask me next time, I would be delighted!” A South East Asian would probably need more words to express a negative: “Oh! How nice, the cinema, do you remember last time we went, yes, how nice it was, oh, thanks for the invitation, so beautiful of you to do so, but ah, yes, perhaps I shall go, did you ask Susan if she wanted to go with you as well, I know she really wanted to watch that movie you are suggesting, with such a good actress in it….” (and then never go). Figure 4.1 illustrates the different ways in which people from different cultures have a tendency to communicate. Whereas Scandinavians and other Northern Europeans have a preference to “get to the point” or “focus on the nitty gritty straight away”, Latinos prefer to sugarcoat their messages, in particular if these have a negative component. In Asian cultures, the context is very important, but relationships are even more important that the point of the discussion may never be reached, which is not so crucial.

Rhetorical Styles Potentially Leading to Miscommunication Across Cultures

The following passage describes an interesting example of miscommunication between high and low context cultures.

A company is just a big team (team defined as “two or more people working together in a common way for a common goal”). Needed are reasoned discussions towards mutually acceptable solutions and frank exchanges of opinions and disagreements. All types of teams, sports, business, or marriage, are only as strong as the ability of team members to cooperate and work together. Teams fail without good communication.

People with experience in alien cultures, through travel or work, know that different cultures do things in different ways. Common examples are giving gifts, who sits where at dinner, and the way cultures use language to communicate.

“Use language” does not mean grammar, pronunciation, or vocabulary. These are called language “skills.” By logic it’s obvious that a certain degree of language-skills-in-common are necessary for cross-cultural communication, but “skills” are just a beginning, not an end.

Maybe the best way to explain this is to use a situation most people are familiar with: husband wife communication. In my case, though, it’s not just a male-female problem, but also a Chinese-Western one. Some background: my (Chinese) wife and I have been married five years, have Master’s Degrees, good second-language skills and far-more-than-average experience dealing with people from different cultures. In other words, we should have few problems communicating with each other. How I wish that was true. It’s not: we argue more about communication than any five other things.

How could that be? We understand (and love) each other, understand each other’s culture, and speak each other’s language. Women first: her (common) complaints are “You use Chinese like a Westerner: you are too direct, especially when you ask questions and analyze situations; you use too much logic and not enough feelings; you embarrass people by discussing the good and bad points of their proposal in front of others, you are just too rude and not polite enough.” To put that in perspective, my family and long-time Canadian friends continually remark on how much more reserved and less aggressive I’ve become since living in Asia.

My turn. My wife’s English is excellent (better than my Chinese), but I go crazy every time I ask her a direct, yes/no question (something like “Do you think I should do this?”). While she does answer me, only very rarely does she use the words “yes” or “no.” Instead, she tells a story (of sorts), and from what she says, and how she says it, and her body language, I must guess her answer. The short reason why is because there are no words for “yes” or “no” in Chinese. Classified as “high context language,” Chinese (all dialects, Mandarin, Cantonese, etc.) is designed to maintain harmony at all costs, not to be clear. The goal is communicating negatives without actually saying “no.” It works for Chinese, but as it is based on the ability to guess meaning, it is tough for Westerners to master—we don’t practice making people guess, and have little problem saying “no” when necessary.

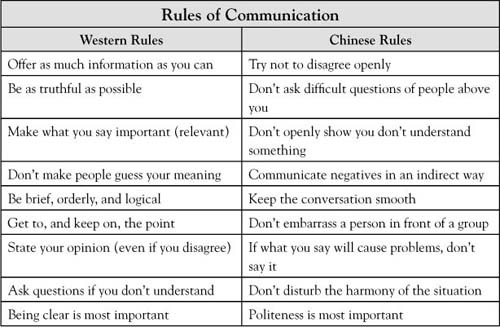

Each culture expects language to be used in a specific way. We all grow up learning the right way to use language. Often called “learning how to be polite,” it goes far deeper than just politeness. We learn rules—rules that determine our belief in the right and wrong way to use language. Called the Rules of Communication, they determine how we feel language should be used. Language is but a tool used in culturally specific and unique ways.8

High/Low Context and Other Frameworks for Cultural Analysis

Individualism Versus Collectivism

In collectivist cultures, in which harmony and relationships are to be taken care of, direct, simple, straightforward statements are to be avoided. A straight truth could not only hurt and break links that have taken time to develop; but hurting someone may not just mean that the specific relationship might break up, but also that the network of relationships may be altered.

If someone makes someone else lose face through straight confrontation, this may affect the relationships between families, business partners, guanxi (personal networks and networks of networks, in the Chinese sense of the term), and more. One must be very careful to use the right tone, at the right moment with the right person in collective societies, as the actions of the individual (and his/her words!) have an impact that goes beyond just themselves.

Specifics Versus Diffuse

Individuals from diffuse cultures often communicate using high context because all the areas of their lives are strongly interconnected. A dispute with someone at work will affect all relationships at all levels: village level, country club level, meeting at children’s school level... therefore communications have to remain smooth and polite.

In specific cultures what one person thinks of another as a worker has nothing to do with the way he or she is considered as a parent, a neighbor, a citizen, etc. Therefore, direct speech is more frequently used in these cases.

Synchronics Versus Sequentials

In sequential cultures, what happened in the past remains mostly in the past so direct forms of expression are allowed, as the consequences of any sort of vexation would not go far beyond a short time period and there is always the chance to start afresh. In synchronic cultures, much attention is paid to the image left through one’s expression as the past is always present, even in the future, so it is important to always give a good impression. Hurting somebody in the present will certainly have an impact in the future.

Human Activity Versus Human Nature (or Achievers Versus Ascribers)

In achievement oriented cultures, signaling errors or communicating directly could be perceived as a useful way to help others in their search for perfection. Information being a key success factor and a valuable asset, it is important to be as clear, concise, and concrete as possible, as this allows not only each person to make sure there is no doubt about “the deal,” but it can also be considered as a sign of respect towards those whose decisions would be more accurate if they had all the facts in hand.

In ascribed societies, respect and acknowledgment of the role assigned by the group are a sign of respect and modes of communication should at every moment express the adhesion to the tacit norms and hierarchies. Arriving late to a meeting, for example, could be a way to express that someone is highly ranked, the same way that bringing a lawyer to a negotiation could also be a means to say that trust has not been established yet.

Relationship With Nature (Internal Versus External Locus of Control)

In external locus of control cultures, it is perceived that human beings cannot master the universe, truth, Nature, or other forces. Therefore, pretending that anything is objective, indisputably truthful, or absolute does not mean much. Being precise on matters relating to life, which is anything but precise does not make sense. What does make sense is harmony and peace, therefore much attention is paid to how things are said, rather than to what is said.

In contrast to that, in internal locus of control cultures, the need to master the universe makes it necessary to provide as much information with as much clarity as possible so that it becomes possible to react to facts with the maximum chance of obtaining the goals set. Therefore, being explicit becomes a sign of respect towards those who would then use the objective information given to proceed in life.

Power Distance

In high power distance societies, rank needs to be acknowledged and reminded at all times, and one very useful way to do that is through implicit communication: private lifts will communicate power the same way that private parking lots would do. Never contradicting the boss in public even if the information that you could be providing him or her on the spot would help him or her do a better job is crucial to survive in this type of societies. Information is hardly ever distributed evenly in these societies, so highly ranked people see no real point in discussing much with subordinates. Communication consists basically in having lower ranked individuals show admiration and respect through signs and symbols and highly ranked ones responding to such actions the same way.

In low power distance societies, information is more likely to flow fast to the key decision makers, so being explicit is usually appreciated.

The Exception to All the Rules: Great Britain

Great Britain appears as an interesting example as this culture challenges all the expected behaviors as explained above. Scoring low in power distance, recognized as internal locus of control oriented, promoting achieving behavior, being individualistic and synchronic; Britain still remains a country that communicates implicitly, even with words (for example, see the table at http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-SPrrw9CrJf8/Tc5eDJkimII/AAAAAAAACYE/KLKNblvj1Bo/s1600/5gxvx-724032.jpg).

It is interesting that even if all Anglo-Saxon cultures tend to share very similar rankings in all frameworks, when it comes to context, results vary significantly showing that the Brits are the only Anglo-Saxons to communicate indirectly. There is something specific in the British way of communication that can be upsetting to foreigners, particularly North Americans, who often consider themselves separated from the British by a common language.

Perhaps a colonial tradition followed by strong waves of immigration has not simply led to the worldwide use of English as the main foreign transactions language. Another collateral consequence of this fact could have been the need to recreate a language inside a language that would work as an internal social cohesion factor. Most societies find language as one of the most important indicators of social inclusion, or of cultural belonging. In the case of the UK, because their national language is so widespread, they had to reinvent many codes so that the “inclusion by exclusion” dynamic can continue to take place and the nation would not be completely left without its main identity shaping characteristic.

Human Nature

The second framework that neither Trompenaars nor Hofstede considered was human nature.

The human nature framework describes what the basic nature of people is understood to be in different cultures. For some, most people are evil and cannot be trusted; therefore they need to be controlled. For others, there are both evil and good people in the world, and therefore it is necessary to investigate people before trusting them. But people can be changed with the right guidance. Finally, there are cultures where people are considered to be good at heart, as they are born good.

The interpretation of humanity in these terms has serious consequences in management. Can employees be trusted or do they need to be followed up? The same occurs at a political level, and the philosophies supporting the notion that evil is natural have justified the use of dictatorial regimes to “restore peace.”

Studies like Stanley Milgram’s9 on obedience to authority have shown that under certain circumstances men can hurt those who have not aggressed them. Other theories of universal values (Rokeach, Hofstede, Schwartz) have produced value concepts sufficiently similar to suggest that a truly universal set of human values does exist and that cross-cultural psychologists are close to discovering what they are (Michael D. Hills, University of Waikato, New Zealand). For more information on this upcoming theory, see http://orpc.iaccp.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=51%3Amichael-d-hills&catid=24%3Achapter&Itemid=2.

In any case, rankings on this framework have not been produced, and therefore it is difficult to develop hypotheses or even to comment on origins, causes, and consequences of these mental programmings.

In the following exercises, we invite readers to reflect on the topic, position cultural groups according to their own experience, and self-evaluate their own conceptions and convictions on the matter.

Using This Informations

This chapter explains the remaining frameworks that the latest research in cross-cultural management has produced. They, in conjunction with the ones that we previously used, provide an overall view on cultural differences arising from specific mental programmings.

The understanding of the cultural dimensions by all authors facilitates the understanding, prediction, and interaction with cultural behavior in international business.

Exercises

1. Go to http://www.blogcatalog.com/discuss/entry/human-nature-good-or-evil and comment on the discussions by people participating on this blog.

2. What is your own opinion on the matter? Do you think your opinion is the result of cultural influences playing on you as a person? If so, how? If not, why not?

3. List a few potential consequences for a society of having people who conceive humans as evil/good/in-between.

4. Imagine a dialog between someone from a high context culture and someone from a low context one. Point out potential areas of misunderstanding.