One. Personality Traits

When I was in high school, I signed up for the student newspaper. To get me started, the editor offered some standard advice on how to write a story. He said I should be sure to answer five questions: What happened? Who was involved? When? Where? Why? He said that knowing about these “five Ws” served as a check for completeness because novices sometimes left out one or more of them. He then assured me that I wouldn’t need them for long because answering these questions was something I was already inclined to do intuitively.

Intuition is also what journalists rely on when they size up people. Through years of practice, they develop a knack for identifying distinctive personality traits and finding the words to describe them. The gifted among them are so good at it that they can create a revealing portrait in a single paragraph. Consider, for example, Joe Klein’s description of the personality of an American politician:

There was a physical, almost carnal, quality to his public appearances. He embraced audiences and was aroused by them in turn. His sonar was remarkable in retail political situations. He seemed able to sense what audiences needed and deliver it to them—trimming his pitch here, emphasizing different priorities there, always aiming to please. This was one of his most effective, and maddening qualities in private meetings as well: He always grabbed on to some point of agreement, while steering the conversation away from larger points of disagreement—leaving his seducee with the distinct impression that they were in total harmony about everything. ... There was a needy, high cholesterol quality to it all; the public seemed enthralled by his vast, messy humanity. Try as he might to keep in shape, jogging for miles with his pale thighs jiggling, he still tended to a raw fleshiness. He was famously addicted to junk food. He had a reputation as a womanizer. All of these were of a piece.1

Notice that Klein needs only a handful of evocative words to highlight the main characteristics of his subject: carnal, needy, messy, maddening, fleshiness, addicted, and womanizer. To round out his description, he uses a few short phrases, such as “his sonar was remarkable,” “high cholesterol quality,” and “aiming to please.” When he can’t find a simple word or phrase to describe something that he considers particularly revealing, he makes up a whole sentence: “he always grabbed on to some point of agreement, while steering the conversation away from larger points of disagreement—leaving his seducee with the distinct impression that they were in total harmony about everything.” By using words and phrases that all of us can understand, Klein tells us a great deal about the personality of an extraordinary public figure: Bill Clinton.

The combination of words and phrases is, of course, critical. There are other people who are needy but who are neither carnal nor womanizers. Some of them may also have remarkable sonar but without being messy or maddening. What makes Klein’s description so recognizable is that, as he points out, all the traits “were of a piece.”

So how did Klein do it? Was he intuitively asking himself a set of questions that are as obvious to him as the five Ws? Did he leave out anything important? Can we learn a technique to make our own descriptions of people more incisive and complete?

Words from the Dictionary

The development of a simple technique to describe personalities was set in motion in the 1930s by Gordon Allport, a professor of psychology at Harvard. Although Allport was well aware of the uniqueness of each individual, he also knew that scientific fields get started by breaking down complex systems into simple components. Just as understanding the great variety of chemical compounds depended on identifying a limited number of elements, understanding the great variety of personalities may depend on identifying a limited number of critical ingredients. But what exactly are those ingredients?

Allport’s answer was traits: the enduring dispositions to act and think and feel in certain ways that are described by words found in all human languages. Just as chemical elements such as carbon and hydrogen can combine with many others to form endless numbers of complicated substances, traits such as being outgoing and being reliable can combine with many others to form endless numbers of complicated personalities. But how many traits are there? And how could Allport find out?

To answer this question Allport and his colleague, H.S. Odbert, made a list of the words about personality from Webster’s New International Dictionary.2 By analyzing this list, they hoped to identify the essential components of personality that were so obvious to our ancestors that they invented a great many words to describe them. Instead of just concocting an inventory of personality traits out of their own heads, Allport and Odbert would be guided by the cumulative verbal creations of countless minds over countless generations, as recorded in a dictionary.3

It soon became clear that these researchers had bitten off more than they could chew. The list of words “to distinguish the behavior of one human being from another” had 17,953 entries! Faced with this staggering number, they whittled it down using several criteria. First, they eliminated about a third, such as attractive, because the entries were considered evaluative rather than essential: “[W]hen we say a woman is attractive, we are talking not about a disposition ‘inside the skin’ but about her effect on other people.”4 Another fourth hit the cutting room floor because they describe temporary states of mind, such as frantic and rejoicing, rather than the enduring dispositions that are defining features of personality traits. Others were thrown out because they were considered ambiguous. In the end, about 4,500 entries met the researchers’ criteria for stable traits.

This doesn’t mean that personality has 4,500 different components; many of the words on the list are easily identifiable as synonyms. For example, outgoing and sociable are used interchangeably. Furthermore, antonyms, such as solitary, describe the same general category of behavior, but at its opposite pole—instead of saying “not sociable” or “not outgoing,” we might say “solitary.” In fact, a wonderful feature of natural language is that it lends itself so well to a graded (or dimensional) description of specific components of personality, from extremely outgoing at one pole to extremely solitary at the other, with modifiers to specify points in between. Put simply, the ancestors who gradually built our language—and all languages—left us with many choices for describing ingredients of personality.

Recognizing that outgoing and solitary both refer to aspects of an identical trait, how many other words also fit into this category? When I looked up outgoing in my thesaurus, I found these synonyms, among others: gregarious, companionable, convivial, friendly, and jovial. When I looked up solitary, I got, among others, retiring, isolated, lonely, private, and friendless. This tells me that the group of experts who put together this thesaurus decided that all these words belong in a box that can be labeled Outgoing–Solitary. Needless to say, each word in the box may also have some special spin of its own. For example, solitary, lonely, and private don’t mean exactly the same thing, and writers such as Joe Klein may mull them over to get just the right one. Nevertheless, we all know that these words have a lot in common. To psychologists such as Allport, they all refer to a single overarching trait.

Beyond Synonyms and Antonyms

Does this mean that we can identify the essential building blocks of personality by simply getting a list from a dictionary and then lumping together the synonyms and antonyms from a thesaurus? Can we base a nomenclature of personality on the analysis of professional lexicographers? Or can we use a more open-source approach that pays attention to the ways ordinary people employ words to describe personalities?

The answer psychologists settled on was both. First, professionals reduced the list to a more manageable number—about a thousand. Then they asked ordinary people to use these words to describe themselves and their acquaintances. To get an idea of the way this was done, please apply the ten words in the following list to someone you know well. In expressing your opinion, use a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 indicating that the person ranks very high, 1 indicating that the person ranks very low, and the other numbers indicating that the person falls somewhere in between.

I have no way of knowing what numbers you selected. But chances are good that they will have a characteristic relationship: The numbers you picked for the first five items probably are similar, and the numbers you picked for the second five items probably are similar. Furthermore, I can say with confidence that most people who give someone a certain score for outgoing give them a similar score for bold, talkative, energetic, and assertive; and that the score they give someone for reliable is likely similar to the one they give for practical, hardworking, organized, and careful. Even though none of the words in each quintet are synonyms, people who are ranked a certain way on one word from each tend to get similar scores on the others. In contrast, people’s scores on the first quintet are independent of their scores on the second quintet. This implies that these non-synonymous words are grouped together in our minds because each refers to some aspect of a related component of personality.

Could any other words be lumped together with outgoing or reliable to flesh out these two big categories? How many other groupings like this would be discovered if people were asked to make judgments using all the thousand words that the original list was pared down to? And what statistical techniques would be needed to identify these categories? In making the list, Allport set the stage for research on these questions.5

Bundling Traits

A statistical technique for studying the relationships between these words was invented in the nineteenth century by Francis Galton, a founder of modern research on personality, whom you’ll read more about later. The technique is used to calculate a correlation coefficient, a number between 1.0 and −1.0 that measures the degree of sameness (positive correlation) or oppositeness (negative correlation). Although Galton invented the technique for other purposes, he also happened to be interested in categorizing the words that we use for personality traits,6 and he would have been pleased to learn about this application.

To get a feel for this calculation, let’s think about the positive correlations we would find if we asked people to rank someone on outgoing, sociable, and gregarious by using a scale of 1 to 7. Knowing that these words are synonyms, we would expect to find that if John ranks Mary a 6 on outgoing, he likely will rank her around 6 on each of the others. If he then ranks Jane as a 4 on outgoing, he likely will rank her around 4 on each of the others. And if Jennifer ranks Jim a 1 on outgoing, she likely will rank him around 1 on each of the others. Plugging these scores into Galton’s formula would indicate a great deal of sameness.

Now what sort of correlations would we find between the words in the first non-synonymous quintet (outgoing–bold–talkative–energetic–assertive)? Studies show that these words are correlated strongly, but not as strongly as synonyms, and similar positive correlations are found among the words in the second non-synonymous quintet (reliable–practical–hardworking–organized–careful). In contrast, when we compare the scores for words such as outgoing from the first group with words such as reliable from the second group, we don’t find a correlation. This comes as no surprise because we all know that being outgoing and being reliable are not intrinsically related.

Determining the correlations among five or ten words is fairly easy. But determining the correlations among a thousand words was stalled until researchers could turn it over to a computer. To get the raw data, thousands of ordinary people were asked to apply each of these words by ranking their applicability to themselves or another person using a scale of 1 to 7. The mass of data was then analyzed with a more advanced statistical technique, called factor analysis, which measures the correlation between each word and all the others and organizes the correlations into clusters. In this way, some words were identified as highly correlated to each other, making them good representatives of a particular cluster, which psychologists call a domain.

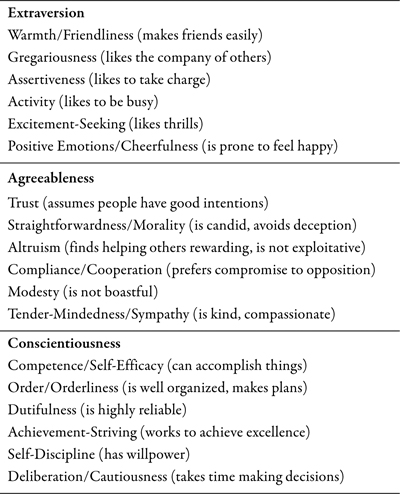

By the early 1980s, the results were in: The words that describe personality traits can be boiled down to just five large domains (see Table 1.1), which Lewis Goldberg named the Big Five.7 Each of them has been given a reasonably descriptive name: Extraversion (E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Neuroticism (N), and Openness (O). If you have trouble recalling these names at first, as I did, you can use the acronyms OCEAN or CANOE to jog your memory until they become second nature.

Table 1.1 The Big Five: Representative Words

Using the Big Five

After the Big Five was discovered, it became the foundation for assessing individual differences in the ways people interact with their social and physical worlds. Three domains—Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism—mainly relate to ways of interacting with other people. The other two—Conscientiousness and Openness—are more general.8

• Extraversion is the tendency to actively reach out to others. People high in Extraversion are stimulated by the social world, like to be the center of attention, and often take charge. They also like excitement and are inclined to be upbeat, fun loving, full of energy, and to experience positive emotions. People low in Extraversion are less interested in interpersonal interactions and tend to be reserved and quiet. But their relative lack of interest in being with people need not indicate that they don’t like them, or that they are socially anxious or depressed; they may just prefer to be alone.

• Agreeableness is the tendency to be altruistic, cooperative, and good-natured. People high in Agreeableness are considerate, compassionate, helpful, and willing to compromise. They truly like people and assume that everyone is decent and trustworthy. People low on Agreeableness are more self-interested than altruistic, more competitive than cooperative, and likely to be skeptical of others’ intentions. They also tend to be cold, antagonistic, and disrespectful of the rights of others.

• Conscientiousness is the tendency to control impulses and to tenaciously pursue goals. People high in Conscientiousness are orderly, reliable, hardworking, neat, and punctual. They tend to plan ahead and think things through. They are more interested in long-term than short-term goals. People low in Conscientiousness are more spontaneous, less constrained, less dutiful, and less achievement-oriented. Although Conscientiousness shows up prominently in the performance of tasks, it also influences interpersonal relationships.

• Neuroticism is the tendency to have negative feelings, particularly in reaction to perceived social threats. People high in Neuroticism are emotionally unstable, tend to be upset by minor threats or frustrations, and are often in a bad mood. They are prone to anxiety, depression, embarrassment, self-doubt, self-consciousness, anger, and guilt. People low on Neuroticism are emotionally stable, calm, composed, and unflappable. But their freedom from negative feelings does not imply that they are particularly inclined to have positive feelings.

• Openness is the tendency to be imaginative and to enjoy novelty and variety. People who are high in Openness tend to be artistic, nonconforming, intellectual, aware of their feelings, and comfortable with new ideas. People low in Openness prefer the simple, straightforward, familiar, and obvious to the complex, ambiguous, novel, and subtle. They tend to be conventional, conservative, and resistant to change. Although people who are high on Openness enjoy the life of the mind, Openness is not identical with intelligence. Highly intelligent people can be high or low on O.

After you’ve mulled over the broad meanings of these five domains, you can get a better sense of them by applying them to someone you know. You might start by asking yourself how outgoing, good-natured, reliable, moody, and creative that person is compared with others. In doing this, you will notice that the person’s relative rankings vary somewhat depending on the situation.9 For example, a person may be outgoing with friends but shy with strangers, so you have to decide on the average scores by summing up the many observations you’ve made.10 From this, you will come away with a profile of the person’s basic tendencies, such as moderately extraverted, very agreeable and conscientious, a little neurotic, and very open. Although this is no more than a rough summary of how you regard this person, the Big Five framework will have helped you put your intuitive assessments into words. You will then be in a position to more thoughtfully compare this person with others by seeing his or her differences more clearly.11

Big Five 2.0

Having made such assessments, you may find that your ideas about each category are still fuzzy. To sharpen your appraisal of a person’s profile of traits, it helps to move from a holistic impression to a more meticulous examination. To do this, you need to learn more about the details of the Big Five.

Paul Costa and Robert McCrae have done the most to clarify these details. Working together at the National Institutes of Health in the 1980s, they developed a questionnaire called the NEO-PI R, which uses phrases rather than adjectives.12 The big advantage of using phrases is that you can design them to eliminate some of the ambiguity that is inherent in single words. For example, in place of the word insecure, a component of Neuroticism, Costa and McCrae use phrases that spell out certain aspects, such as: “In dealing with people, I always dread making a social blunder” and “I often feel helpless and want someone else to solve my problems.”13

Another reason for the popularity of the NEO-PI R is that it sharpens the assessment of each of the Big Five by subdividing them into six components, called facets. This ensures a more complete evaluation and helps focus attention on specific individual differences. Consider for example, these phrases that assess facets of Extraversion:

• I find it easy to smile and be outgoing with strangers. (Warmth/Friendliness)

• I enjoy parties with lots of people. (Gregariousness)

• I am dominant, forceful, and assertive. (Assertiveness)

• My life is fast-paced. (Activity)

• I love the excitement of roller coasters. (Excitement-Seeking)

• I am a cheerful, high-spirited person. (Positive Emotions/Cheerfulness)

The advantage of using these facets is that it may help you make distinctions that you might have glossed over. For example, many people with an average E score are not average across the board. Some may be somewhat higher on warmth, gregariousness, and positive emotions than on assertiveness, activity, and excitement-seeking; others may have a different balance of tendencies. The same is true for the other major traits. In each case, you should pay particular attention to facets that stand out as clearly higher or lower than average. Because the whole point of the exercise is to compare people with each other, you’re really looking for these distinguishing characteristics. You may also take note of particular situations in which these distinguishing characteristics are expressed.

To get a feel for the facets of the Big Five, I encourage you to take a free computer-based personality test that resembles the proprietary one devised by Costa and McCrea, at www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/j/5/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm. Developed by a group of distinguished personality researchers14 and overseen by John A. Johnson15 at Pennsylvania State University, it uses different names for some of the facets but covers similar ground. This free test, called the IPIP, can be taken anonymously in about 20 minutes. If you take it, you will receive an automated e-mail report that shows your relative rankings on the Big Five and its facets by comparing your scores with those of the hundreds of thousands of other people who have already taken it.

To gain more experience with the facets of the Big Five (Table 1.2), you may also use the online questionnaire to assess a person you know. Scoring the person on this list of items not only will sharpen your view of him or her. It will also increase your familiarity with this technique. As you become more familiar with the Big Five, you will learn to make such judgments in your head without relying on a questionnaire.

Table 1.2 Facets of the Big Five*

Rethinking Bill Clinton

Another way to get a feel for the Big Five and its facets is to keep it in mind while re-examining the paragraph from Joe Klein’s book that I cited at the start of this chapter. Klein tells us much more about Clinton’s personality than he packed into this paragraph. But for our purpose, I mainly stick to those 165 words:

There was a physical, almost carnal, quality to his public appearances. He embraced audiences and was aroused by them in turn. His sonar was remarkable in retail political situations. He seemed able to sense what audiences needed and deliver it to them—trimming his pitch here, emphasizing different priorities there, always aiming to please. This was one of his most effective, and maddening qualities in private meetings as well: He always grabbed on to some point of agreement, while steering the conversation away from larger points of disagreement—leaving his seducee with the distinct impression that they were in total harmony about everything. ... There was a needy, high cholesterol quality to it all; the public seemed enthralled by his vast, messy humanity. Try as he might to keep in shape, jogging for miles with his pale thighs jiggling, he still tended to a raw fleshiness. He was famously addicted to junk food. He had a reputation as a womanizer. All of these were of a piece.

As we noted before, Klein built his description by calling attention to a few key traits. But now we can translate the information that Klein provides into the language of the Big Five. Needless to say, much more is known about Clinton, and other observers have painted a somewhat different picture than Klein did.16 But let’s stick with the paragraph and some other information from his book to illustrate how the Big Five and its facets can help us organize our thoughts about Clinton’s basic tendencies. To do this, I will concentrate on facets in which his scores are notably high or low.

Starting with Extraversion is particularly fitting when considering Clinton because he loves to be the center of attention. Klein emphasizes this with evocative terms for his public appearances, such as “embraced audiences” and “aroused by them,” which translate into very high scores on gregariousness. Clinton is also obviously high on assertiveness, which led him to the most powerful leadership roles, and “womanizer” can be considered partly a reflection of high excitement-seeking. From this and everything else Klein tells us, Clinton ranks high on all facets of Extraversion, and his overall score is at the top of the chart.

Klein also gives us some information about Agreeableness, but Clinton’s score isn’t quite so obvious. From the paragraph, you may first get the impression that he ranks high on A because he is “always aiming to please.” But as you read on, you will realize that he’s just telling his “seducees” whatever they want to hear. In the course of his book, Klein gives many other examples of Clinton’s deceptiveness, which gives him a low score on straightforwardness. Klein also presents evidence that Clinton’s womanizing is exploitative, which lowers his score on altruism and sympathy. When taken together Clinton’s Agreeableness, which appears very high on first meeting him, is lower than it seems.

The information we get about Conscientiousness is limited but revealing. The part about jogging indicates an effort at self-discipline. But this impression is tempered by “try as he might to keep in shape,” “raw fleshiness,” “addicted to junk food,” and “womanizer,” which are hardly testimony to high C. So even though Klein’s paragraph leaves out Clinton’s very high achievement-striving, the lower scores for dutifulness, cautiousness, and deliberation that he documents in other parts of the book combine to give a lower than average ranking on Conscientiousness.

Klein’s paragraph tells us little about Neuroticism except for a hint about “messy humanity.” Other sections of the book tell us that Clinton can get very angry and out of control, but there’s no reason to think of him as being especially prone to negative emotions. In fact, he is unusually capable of brushing off criticism that would make most of us crumble, and he can be cool under extreme fire. When taken together Clinton ranks below average on Neuroticism.

Openness to experience is also not explicitly considered. This omission is not unusual in brief descriptions of people, even though it may turn out to be a distinguishing feature of their personalities. But Klein makes up for this in the rest of the book by providing us with persuasive evidence that Clinton ranks high on most facets of O.

Of course, much about Clinton doesn’t show up in this Big Five profile. But to illustrate the usefulness of this way of describing him, let’s compare it with a similar assessment of another president, Barack Obama, as a way of thinking about their differences. Although Obama has not been in the public eye as long as Clinton, we have already learned a great deal about him from seeing him in action. His two autobiographies fill in many blanks.17

In making this comparison, Openness doesn’t tell us much. Although Clinton and Obama differ in their scores on certain facets, their overall rankings are both high. But their relative scores on Extraversion, Neuroticism, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness are informative. When taken together, very different profiles emerge.

Extraversion is particularly notable because Obama’s overall score is not only lower than Clinton’s, but also lower than the scores of most other successful politicians. Although Obama ranks very high on assertiveness and activity, he is not particularly warm or gregarious. Nor does he show much evidence of positive emotion, even when winning a historic election or a Nobel Prize. Klein, who now covers Obama, offers evidence of his low E from a politician who helped coach Obama for debates during the presidential campaign: “He is a classic loner .... Usually you work hard at prep, and then everyone, including the candidate, kicks back and has a meal together. Obama would go off and eat by himself. He is very self-contained. He is not needy.”18

This low neediness is another sign of Obama’s difference from Clinton: his very low Neuroticism. Whereas Clinton deserves credit for generally controlling resentfulness and discouragement, Obama doesn’t seem to feel them at all, even in the face of strong setbacks. In fact, his remarkable emotional stability, which many admire, has also been criticized as Spock-like. Maureen Dowd, another journalist with a gift for describing personalities, calls him “President Cool” and “No Drama Obama.”19

This coolness might also be taken as a sign of low Agreeableness. But Obama clearly ranks high on several of its facets, especially straightforwardness and cooperation. Although he does not exude either altruism or tender-mindedness, his behavior suggests that they are at least average. So unlike Clinton, Obama is higher on Agreeableness than he might seem.

Obama’s high marks on all six facets of Conscientiousness also distinguish him from Clinton. He ranks especially high on deliberation, examining all sides of a problem. As with other personality traits, this can be seen as a mixed blessing, bringing him praise for his thoughtfulness but criticism that he is too professorial and indecisive.

Considering Obama and Clinton in this way shows how the Big Five can help us organize our intuitive observations by making them explicit. Although the profiles that it generates are sketchy, the process focuses our attention on the full range of basic tendencies, including some that we might otherwise have overlooked. And as you will see, the findings we make in this way provide a framework for describing the personality patterns that I will consider in the following chapter.