Chapter 2

What Is Copyright?

The Constitution of the United States gives Congress power to pass laws in order to encourage authors to create works. The encouragement comes in the form of exclusive rights to their writings for a limited time. Those rights are defined in the Copyright Act. There are only two key requirements to qualify as writings covered by copyright law: fixation and original and creative expression.

Fixation

The work must be fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Expressions come in different forms. They can be words contained in an article or a book; images preserved in photographs or film; sounds secured on sheet music, audiotapes, or CDs; or code stored on computer disks or hard drives. Rules defining how a work is fixed are flexible; over the years, new media have been incorporated. From piano rolls to computer disk drives, the law covers a broad swatch. Thus, the authors of books, articles, movies, tape recordings, snapshots, software, sheet music, newspapers, charts, graphs, choreography, and costumes can all lay claim to copyright protection in their works.

A glaring exception is unrecorded conversations: If words are not fixed, there is no copyright protection. However, flip on the tape recorder and, voila, fixation and hence a copyrightable work. During one of the big trials of the 20th century, the O. J. Simpson murder case, one of the most infamous conversations of recent years, Mark Fuhrman's private conversations about cops and blacks, was recorded without his awareness. The tapes debuted during cross-examination in the trial. They were used to prove something about the state of mind of the witness. But, curiously, by making a tape recording, the aural remarks became copyrighted works. Using them as evidence in a trial is one thing; exploiting them in the marketplace requires a copyright analysis. Had they never been recorded, the world would have lost an insight into the mind of a key witness. In addition, at some time in the future those tapes may have a publishing value. If the tapes are ever exploited, as they are his words, Mark Fuhrman will certainly have something to say about it.

When television was in its infancy, live performances were the norm. Some of these performances were preserved by kinescopes, recordings made off a monitor. The kinescopes qualify for copyright protection. Indeed, what we know about the early days of television, from I Love Lucy to The Honeymooners to Today and Playhouse 90, is owed to those kinescopes. Some of those programs make up formidable parts of valuable cable networks such as Nickelodeon. Even without the kinescopes, many of the old TV performances have a copyrightable form, written scripts. Those scripts are fixed works.

Television's predecessor entertainment medium, vaudeville, with its stand-up comics, was notorious for “gag theft.” The stars of the “Borscht Belt” regularly stole punch lines from each other, but they always did so with a copyright risk. If the gags were scripted, a copyright claim could have been made. However, when the live performances were ad-libbed and no script or underlying text was used and no recording was made, they fell outside the scope of copyright protection. In sum, if a work is fixed in a tangible way, copyright law claims dominion over it.

Original and Creative Expression

The other key for copyright law is that the fixed expression be original and creative. Originality means the work is not copied; creativity means that it evidences at least a modicum of thought. If the expression is extremely short, a word or a phrase, then trademark law takes over. However, string together 15–20 words (much like a poem) and you have sufficient creativity for copyright. But—and this is important—you cannot reproduce another's work and claim protection for it. How much of another's work you can use, with or without permission, is a topic addressed soon. For the moment, it is important to understand that copyright law protects a work's original creator.

The question of how much originality is sufficient for copyright protection is particularly troublesome in the context of photographs. In a controversial decision in 1999 (The Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp.), a New York court held that transparencies and digital images of works of art were mere “slavish copies” (similar to photocopies) and therefore not entitled to copyright protection, although the court believed that the “overwhelming majority” of photographs would have sufficient originality to qualify. Not surprisingly, the case attracted a great deal of comment and criticism.

A copyright maxim that underlies the willingness of the law to protect original and creative expressions is this: Expressions are protectable; ideas are not. For copyright law to coexist with principles of the freedom of speech and the free flow of information, it is vital that ideas and facts not be owned exclusively by anyone. They are the building blocks of speech and knowledge. Therefore, the fact that something happened—a crazed gunman took over a station, ranted for an hour, and then killed himself—is available for anyone to explain, discuss, and put into his or her own words. Copyright law defines ownership of those words. At the same time, the Constitution and the copyright law ensure that anyone can report on those same facts.

The idea/expression dichotomy, as it is known, becomes more complex when a photographic image captures an actual image in place, the narrative of a reporter on the scene embraces the essence of the event, or an author of a historical biography relates events from his subject's life. Trying to put the expression into any other form may be difficult, if not impossible. The quintessential example of this statement is the Zapruder video of the assassination of JFK. That tape, shot by a bystander and later purchased by Time magazine, is a copyrighted work. But it is also the essence of a historic event. Can the visual retelling of that shooting be done without visual quotations from the Zapruder video? An even more profound question from a First Amendment perspective is, Should an author be prohibited from using this work without the consent (and likely payment) to the copyright owner? This question points to the core philosophy of copyright law—the economic incentives of encouraging copyrightable creativity—to which we often return.

A few years ago the U.S. Supreme Court had some things to say about the idea/expression dichotomy in a case involving the telephone directory. The ruling, Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., or Feist for short, held that the names and phone numbers in the telephone books are facts. Facts, as we know, are not copyrightable; therefore, one could copy information from the directories, without asking permission of the copyright owner of the telephone directory. The significance of the ruling was certainly substantial for the telephone industry. Yellow and white pages have proliferated; today, CD-ROMs are sold with 100 million names and numbers; all that information is free for anyone to use. The fact that the original directory was compiled by “the sweat of the brow,” a previously respected basis for developing a copyright, became irrelevant overnight.

For those creative professionals who mold and use content, this ruling has profound implications. Yet, the precise impact on one's works may be uncertain until all the relevant pieces are known. Take the news media, for example. When one's business spends large sums to find facts and be the first to report them, “ownership” of those facts becomes vital. As employees of media outlets in a highly competitive business, managers want the public to “see it first” on their station, in their newspaper, on their website. The race to uncover facts, assemble them, and attract a regular audience is what the business is about. However, if facts are not protectable, then guarding information and exploiting it prudently requires great care. Incorporating sufficient expression in the story overcomes the dilemma, at least from the copyright perspective. If facts are presented in a way that is replete with individual expression, then copyright law protects that expression. So Woodward and Bernstein's insider reports on the doings of Watergate were protected, as are Woodward and Balz's detailed reports of the handling of the September 11 crisis by President Bush and his cabinet, while the headline summaries of these articles are not. Similarly, the photo of the soldier and the girl kissing in Times Square to mark the end of World War II was reality, but one captured with a creative photographic artistry respected by copyright. Even the videographer who happened to train his camera on some cops beating up Rodney King achieved something more by framing his story and zeroing in on the event. He made a video that copyright law protects.

Sometimes, what appears to be a fact—say, the overnight rating of a popular television program—is often more complex from a copyright law point of view. The market report, which estimates viewing of television or radio programs based on application of complex research data and statistical analyses, constitutes not a fact but rather the rating service's opinion about the number of people projected to have seen a particular television program at a given time. Thus, that West Wing scored a 16 rating (meaning that about 16 million people watched the show last Wednesday) is not a statement of a fact but one rating service's best guess on the viewing total. What is more, another research firm might reach a different result, even with identical raw data. Therefore, those rating reports are copyrightable, even though they represent one entity's attempt to define the “facts” of the viewing marketplace.

Contrast the statement that 16 million viewers watched a television program with the statement that 16 million Hispanics voted in the 2000 election. If the statement about voters is the result of an electoral tabulation, that number is a fact that others can exploit without fear of copyright reprisal.

That Feist is having an important impact on the collection and exploitation of information is unquestionable. In the 1990s, when Congress modernized copyright law for the digital millennium, a burning issue was database protection. Creators of databases, or collections of information, vigorously complained that their investment in constructing and maintaining databases was being seriously eroded by unrestrained application of the Feist principles. Proponents asked Congress to amend the Copyright Act by creating a body of laws designed specifically to protect data. They argued not that their data is copyrighted—that path was foreclosed by the Supreme Court—but that they made an investment in finding the

data and maintaining the database. The “datamining” investment should be protected from third party uses that are unauthorized and uncompensated. The effort stalled, and a DMCA compromise required that the database title be removed from final legislation. But this issue persists. Congressional committees have asked interested parties to participate in a series of negotiations to see if a compromise on the matter can be worked out. We devote more attention to database protection later in the book.

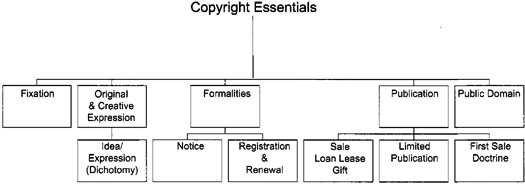

Four other introductory concepts should be explained (Figure 2-1): the public domain, copyright formalities, publication, and first sale.

The Public Domain

Here is a concept full of confusion. Works in the public domain are, by definition, not covered by copyright. They are free to be used and reused, with no worry about clearance or compensation. In some cases, public domain works are easy to identify. Remember what was said at the start: the Founding Fathers empowered Congress to grant exclusive rights to works for limited times. In copyright terms, this generally has meant decades, not centuries. Once the term of copyright ends, no restrictions remain on making, distributing, or performing works.

As to the evolution of the statutory term, here is a capsule review. In 1790, the first copyright law set the term of protection at 14 years, with an extra 14 years if the author was still alive at the end of that term. The initial period of protection was extended to 28 years in 1831, with a renewal term of 14 years. Starting in 1909 and continuing until 1977, the copyright term for published works remained 28 years, but if some formalities were followed, it could be renewed for an extra 28 years. From 1978 (when the 1976 Act took effect) to 1998, the copyright law generally granted protection for a period of life of the author plus 50 years, or 75 years from creation in the case of works for hire. With passage of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (CTEA), 20 years were added to the copyright term. Also, special rules apply for unpublished, anonymous, and pseudonymous works, so calculating the precise duration of particular copyrights can be complicated in any individual case. We provide a short primer on the subject in Chapter 7.

CTEA was passed after many years of debate. The law is named for the popular singer-turned-congressman, Sonny Bono. Bono, who personally composed many of the hits he sang with his musical partner Cher, became a well-liked politician after decades of performing. He was a particularly strong advocate for authors' rights. After being elected to Congress, he sponsored the legislation that became CTEA. When he met an untimely death after a skiing accident, Congress chose to honor him by making term extension his legacy. Sonny's legacy, however, may have a dark side. A group of educators and advocates for an expanded definition of the public domain filed a legal challenge to CTEA. In February 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court said it would hear the case of Eldred v. Ashcroft. A key issue before the Court will be whether extending the term of copyright of works already published and new works violated the Constitution's limited times requirement. A decision is due by June 2003.

Here is a big yellow caution light in the public domain: Unpublished works have a totally different time rule. For family heirlooms (private letters and photographs from the 1800s that may be gathering dust in an attic) or the great American novel that someone's great-great-great uncle wrote but never showed anyone, copyright may still apply (more about this later).

The limited term is why many of the great published works of 19th-century literature (Mark Twain, Herman Melville, or Jane Austen, for example) are exempt from copyright protection. The authors were entitled to exploit their works during the copyright term, but now the works are freely available to be copied by others in original form or adapted to new media. Bear in mind, however, new matter is entitled to a new copyright term. Indeed, changes can effectively transform a public domain work into a protectable copyrighted work. For example, a movie based on a book has its own term of protection; the storyline may be as old as the ages, but the photography, dialogue, music, costumes, scenery, and direction all raise new copyright claims. Recently, an enterprising scholar translated the 1,000-year-old Japanese text, Genji the Shining One. While the work of a millennium ago was written before the English language word copyright was created, the modern translation enjoys the benefits of our legal protections. Anyone can return to the original Japanese and translate the text, but no one can copy the translation without permission.

Many television stations received notices from film distributors who claim to be selling “public domain” movies. If a classic film was registered but the registration was not renewed, then the movie fell out of copyright protection and into the public domain. Rather than pay nasty license fees, these folks provide lists of films that they claim are free of any copyright restraint. With the rising cost of licensing films, these circulars can be pretty tempting. In some cases, they may even be correct. Many films, for reasons that defy commercial logic, were not protected as they should have been. While copyright law permitted the owners to keep the works under the full scope of legal protection, administrative lapses or plain old carelessness permitted the work to drift into the public domain.

When station managers or personnel with any media outlet receive notices about these works, they should do some homework to determine if, indeed, the work is in the public domain. The titles can be identified from the records of the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C. The benefits of this research can be substantial. With the exorbitant costs of securing broadcast rights for programming, obtaining public domain works that retain their broadcast appeal can fit the bill when stations are looking to reduce expenses.

But beware, many of the works touted as in the public domain are not. And some that used to be public domain may have been resurrected by clever entrepreneurs.

A favorite illustration of this point can be found at the National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE) shows of some years ago. NATPE is the broadcast syndication trade show. Vendors of new and old programs sport their stuff there for television affiliates seeking programming products. One enterprising executive discovered that the old Basil Rathbone Robin Hood films were in the public domain. The copyright owner of the movies failed to meet the renewal requirement, and the movies' copyrights lapsed. This creative professional had a plan: By adding some new musical score to the old films, he was able to obtain a new copyright for the derivative work, the public domain film with the copyrighted music. Thus, while the principle of public domain meant that the films could be copied or broadcast by any media company without paying a license fee, the new music could not be copied or performed without the executive's consent. While a few original prints of the public domain films were floating around, the newly scored copies contained an updated copyright notice. Unless a broadcaster could secure a copy of the original, it was difficult, if not impossible, to know what was new material and what was old. The executive, who trouped around NATPE dressed à la Robin Hood and his merry men, made a modern morality tale with a twist; he took from the rich (the original movie producer) and gave to the poor (himself).

With digital technology today, the ability of a creative computer graphic designer to review a public domain work and claim new protection is as easy as logging on to a computer and utilizing specialized software that changes color and content at the creator's fancy. In photography and graphics, for example, the ability to make subtle but copyrightably meaningful changes in form and color permits the blending of an old work into a new copyrighted creation.

In addition to works for which copyrights have lapsed, works of the federal government are exempt from copyright protection. The works of the federal government, whose creation is funded by tax dollars from all citizens, are not entitled to copyright protection by statutory decree. This means that many works, such as government films produced by military filmmakers, reports released by federal agencies, and photographs taken from U.S. satellites, may be copied.

Even with a clear statutory dictate, however, there is a cautionary note to interject: If the government works were made under contract with a nongovernment entity or individual, then the contract covering the creation of the work may transfer the copyright interest to the independent contractor. This crucial limitation, which can wreak havoc with plans to use government works, is often misunderstood. Therefore, if the actual creator of a work published by the U.S. government is not an employee of the government, that creator may have a legal claim to copyright in the final work. For example, film footage of U.S. troops landing during the war in Afghanistan shot by a cameraman accompanying the forces looks like a government work. But, if the photographer was not a U.S. military employee but rather a private photographer hired to accompany the soldiers, that video may be used by the government, but it is owned by the photographer. One would have to review the contract between the military and the individual to know for sure.

With contracts like these generally inaccessible, what is a copyright maven to do? First of all, look at any notices published with the footage. Is there a copyright notice? Is any other legend associated with the tape? If so, in whose name is it? Assuming that information is not available, recall how the tape was obtained. Was it released to the media during a press briefing and, if so, by whom? Was it downloaded from a channel, and, if so, whose? Was there any accompanying printed text? Doing your copyright homework is a necessary chore.

Copyright Formalities

Copyright law used to be laden with formalities. This was a relic of the English legal tradition from which U.S. copyright standards developed. For almost two centuries, American copyright proprietors had to follow the rigors of the system or risk losing all of a work to the public domain. Therefore, formalities such as notice and registration after publication had strict requirements. Disobey these rules and you almost always lost your right to copyright protection.

Today, all those requirements have been eliminated as a by-product of the U.S. government's decision to join the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Property in 1988. Berne, the leading international copyright treaty, defines the terms by which its members must live and provide copyright rules in their countries (see Chapter 19). While the convention allows each member nation certain flexibility in conforming its laws to the terms of the treaty (so-called national treatment), the Berne Convention resolves that the copyright owner should not be subject to formalities to enjoy copyright rights. Hence, in 1988 U.S. copyright law finalized a process begun in 1976, which stripped the law of formal requirements to smooth the way for entrance into a key part of the international copyright community. This is not to say that, prior to 1988, the United States was not already a world copyright leader; indeed, it was the leader. Moreover, by other multicountry and bilateral treaties, the United States had copyright relationships with most of the industrialized world. But the Berne Convention offered special legal access for U.S. copyright proprietors, especially owners of films and software, enabling them to attack directly the growing problem of international copyright piracy, the commercial theft of their copyrighted works.

Prior to the 1976 Act, the formalities of U.S. copyright law were one of its enduring and distinguishing features. Indeed, for users and owners of copyrighted works, formalities offered vital information: Since publication required notice of ownership, one could tell who claimed ownership of works simply by looking for notice. Works published without notice risked being thrown into the public domain, and registration was required promptly after publication. However, in one of the more noticeable efforts of judges to modernize the copyright law without waiting for congressional action, courts ultimately interpreted the obligation to register “promptly” after publication to mean registering any time within the initial term of copyright, that is, within 28 years of publication.

Nevertheless, until 1978 (when the 1976 Act went into effect), the formal requirements of copyright law were essential guidelines affecting the legal status of works. As explained in the discussion on public domain, careful research regarding an author's compliance with these rules can yield proof that the works that look like they should be under copyright are actually free for anyone to use.

For those in the know, copyright law provides the possibility to salvage even works thought to be public domain for many years. For example, the Frank Capra classic, It's a Wonderful Life, became a Christmas season staple when its copyright lapsed—the owner forgot to follow the formality of renewal and the movie fell into the public domain. However, an enterprising film distribution company, Republic Pictures, recently claimed that it held the copyright to the underlying script for the film and therefore telecast of the film without its consent is copyright infringement. Strange as the result may seem, this is sound copyright theory. Legal precedent has held that the copyright in the underlying script from which the film is derived is a separately copyrighted work. Even if the copyright in the film has lapsed, the owner of the underlying story may claim rights to the film as a derivative work (more on this later). For broadcasters, caution may be necessary next time they decide to air this Christmas classic. A check with a copyright lawyer will tell you whether Republic Pictures has succeeded in enforcing its claim.

Publication

When copyright law was updated in 1976, Congress merged all copyright principles into a unitary federal system. In the process, it eliminated the notion of common law copyright. Prior to this reform, if a work was unpublished it could remain the exclusive property of its owner and his or her heirs forever. The critical dividing point was publication. When a work was sold, loaned, licensed, or given away, the law deemed the work published and subject to all the formalities of federal law. Because the dividing point between published and unpublished works had dramatic legal consequences, an entire body of copyright law interpreting the concept of publication evolved.

One important rule in this area is that performance is not considered publication because no copy changes hands. Hence, live concerts are not publication of a musical score. By analogy, when broadcasting began to have an impact on copyright law, it was ruled that a telecast was not a publication of a work. If copies were sold or given away, that constituted a copyright publication, but the mere airing of a program on radio or television did not constitute publication. Thus, all the old network radio shows, which were broadcast live in many cases, with recordings made simultaneously, did not constitute published copyrighted works.

This means that a body of works for which copyright registration was not secured remained under common law copyright protection. Only if tapes of the shows were distributed would the program cross the copyright divide. At that point (prior to 1978), failure to follow the formalities created the potential that the work could fall into the public domain. Complying with the formalities meant that the owner was entitled to claim the benefits of federal copyright for the work during the years it was protectable. Because the consequences of publication without compliance with the formalities were so severe, courts created a limited publication exception. This halfway measure means that a loan of a very limited number of copies—to friends and family, for example—does not equal a divesting publication if formalities are ignored.

While the elimination of formalities has diminished the legal significance of publication, the concept still has important consequences. First of all, when the law was reformed in 1976, common law copyrights were given a federal term of protection. Even though they may have been created a century or more before, the term of copyright protection for unpublished works was extended at least to the year 2002. For works first published between 1978 and 2002, the term will last at least until 2047. Thus, for a vast body of unpublished works, including private manuscripts, photographs, letters, and the like, a cautionary word applies: Even though the works are very old, some even dating back to the early 1800s, they can still be owned and subject to full federal copyright protection. Then, too, several treaties in the 1990s—General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—establish procedures that restore the copyrights of foreigners (see Chapter 19).

First Sale

A copyright doctrine related to publication is called first sale. The core idea of the first sale doctrine is that the law gives the creator of works the right to choose the forum of first publication. In general, the courts have been very solicitous of the copyright owner's right to choose the first release of a work. If a work has not been published and someone wants to exploit it before the owner, the copyright law plants a red flag: “Wait a second.” Almost always, the owner can stop the use.

This principle can even catch the experienced. A few years ago, Random House, one of the nation's leading book publishers, prepared a biography of reclusive author J. D. Salinger. In the book, many private letters written by Salinger were to be published for the first time. Even though Random House and the biographer came by the letters lawfully, the legal issue they faced was whether the book could be published against Salinger's expressed opposition. Anticipating substantial sales based on advance publicity, Random House had a huge first-edition run. To the publisher's dismay, Salinger sued for injunctive relief, demanding on copyright grounds that the publication be halted. The court agreed with Salinger. Salinger, the author of the letters, wanted to control first sale. Through appeals, Random House learned that its case was a loser, a victim of common law copyright and the first sale doctrine. Because Salinger's letters were unpublished, the court reasoned that they were entitled to a higher degree of protection. The First Amendment rights of Random House's author, who sought to bring new insight into the life of this literary hermit, suffered in comparison with Salinger's first sale rights to his private letters. Even though the letters passed from the recipient to another (a limited publication) and someone else owned the physical paper on which his words were written, the copyright to those words remained with Salinger. Random House had to destroy the books in its inventory. Many years still remain before Salinger's rights will be extinguished.

The first sale doctrine as codified by the copyright law also explains why copyright law does not prevent someone from reaping a profit from the sale of an antique book. When an author has benefited from the sale of a copy of his or her work, the law allows the owner of that copy to dispose of it as he or she pleases. It can be given away, sold, loaned, whatever. The copy in which a work is embodied is legally distinguishable from the work itself.

Following the passage of the DMCA, the application of the first sale doctrine to digital works became the subject of special debate. One of the open issues in the DMCA was the relationship of the first sale doctrine to digital works in the form of software, CD-ROMs, DVDs, and so forth. The Copyright Office was instructed to research the matter thoroughly and report to Congress on whether the law needs to be upgraded to deal with the first sale of digital works. The Copyright Office concluded that no changes were needed, rejecting the notion of a digital first sale doctrine. We spend some time reviewing this report and its conclusions in the chapter on digital rights.

This discussion of the first sale offers a useful transition. We now move from a general discussion of the principles underlying copyright law to the rights themselves.